Journal of Researches

The Voyage of the Beagle

Charles Darwin

Information about text on this page  | |

|---|---|

Illustrations in selected editions  | |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS | |

| 1890 | Prefatory Notice |

| Duke of Argyll's Preface | |

| Darwin's Original Preface | |

| 1905 | Concerning the “Beagle” |

| Charles Darwin | |

| I | ST. JAGO—CAPE DE VERD ISLANDS |

| II | RIO DE JANEIRO |

| III | MALDONADO |

| IV | RIO NEGRO TO BAHIA BLANCA |

| V | BAHIA BLANCA |

| VI | BAHIA BLANCA TO BUENOS AYRES |

| VII | BUENOS AYRES TO ST. FE |

| VIII | BANDA ORIENTAL AND PATAGONIA |

| IX | SANTA CRUZ, PATAGONIA, FALKLANDS |

| X | TIERRA DEL FUEGO |

| XI | STRAIT OF MAGELLAN—COAST CLIMATES |

| XII | CENTRAL CHILE |

| XIII | CHILOE AND CHONOS ISLANDS |

| XIV | CHILOE AND CONCEPCION: EARTHQUAKE |

| XV | PASSAGE OF THE CORDILLERA |

| XVI | NORTHERN CHILE AND PERU |

| XVII | GALAPAGOS ARCHIPELAGO |

| XVIII | TAHITI AND NEW ZEALAND |

| XIX | AUSTRALIA |

| XX | KEELING ISLAND—CORAL FORMATIONS |

| XXI | MAURITIUS TO ENGLAND |

| Show King et al Proceedings … (vol. 1) | |

| Show FitzRoy's Proceedings … (vol. 2) | |

| Show Darwin's Journal & Remarks (vol. 3) | |

HMS Beagle track, England to Strait of Magellan  | |

CHAPTER VIII

BANDA ORIENTAL AND PATAGONIA

Excursion to Colonia del Sacramiento—Value of an Estancia—Cattle, how counted—Singular Breed of Oxen—Perforated Pebbles—Shepherd Dogs—Horses broken-in, Gauchos riding—Character of Inhabitants—Rio Plata—Flocks of Butterflies—Aeronaut Spiders—Phosphorescence of the Sea—Port Desire—Guanaco—Port St. Julian—Geology of Patagonia—Fossil gigantic Animal—Types of Organization constant—Change in the Zoology of America—Causes of Extinction.

{1833} HAVING been delayed for nearly a fortnight in the city {Buenos Aires}, I was glad to escape on board a packet {ferry} bound for Monte Video. A town in a state of blockade must always be a disagreeable place of residence; in this case moreover there were constant apprehensions from robbers within. The sentinels were the worst of all; for, from their office and from having arms in their hands, they robbed with a degree of authority which other men could not imitate.

Our passage was a very long and tedious one. The Plata looks like a noble estuary on the map; but is in truth a poor affair. A wide expanse of muddy water has neither grandeur nor beauty. At one time of the day, the two shores, both of which are extremely low, could just be distinguished from the deck. On arriving at Monte Video  I found that the Beagle would not sail for some time, so I prepared for a short excursion in this part of Banda Oriental. Everything which I have said about the country near Maldonado is applicable to Monte Video; but the land, with the one exception of the Green Mount 450 feet high, from which it takes its name, is far more level. Very little of the undulating grassy plain is enclosed; but near the town there are a few hedge-banks, covered with agaves, cacti, and fennel.

I found that the Beagle would not sail for some time, so I prepared for a short excursion in this part of Banda Oriental. Everything which I have said about the country near Maldonado is applicable to Monte Video; but the land, with the one exception of the Green Mount 450 feet high, from which it takes its name, is far more level. Very little of the undulating grassy plain is enclosed; but near the town there are a few hedge-banks, covered with agaves, cacti, and fennel.

November 14th.—We left Monte Video in the afternoon. I intended to proceed to Colonia del Sacramiento, situated on the northern bank of the Plata and opposite to Buenos Ayres, and thence, following up the Uruguay, to the village of Mercedes on the Rio Negro (one of the many rivers of this name in South America), and from this point to return direct to Monte Video. We slept at the house of my guide at Canelones. In the morning we rose early, in the hopes of being able to ride a good distance; but it was a vain attempt, for all the rivers were flooded. We passed in boats the streams of Canelones, St. Lucia, and San Jose,  and thus lost much time. On a former excursion I crossed the Lucia near its mouth, and I was surprised to observe how easily our horses, although not used to swim, passed over a width of at least six hundred yards. On mentioning this at Monte Video, I was told that a vessel containing some mountebanks and their horses, being wrecked in the Plata, one horse swam seven miles to the shore. In the course of the day I was amused by the dexterity with which a Gaucho forced a restive horse to swim a river. He stripped off his clothes, and jumping on its back, rode into the water till it was out of its depth; then slipping off over the crupper, he caught hold of the tail, and as often as the horse turned round the man frightened it back by splashing water in its face. As soon as the horse touched the bottom on the other side, the man pulled himself on, and was firmly seated, bridle in hand, before the horse gained the bank. A naked man on a naked horse is a fine spectacle; I had no idea how well the two animals suited each other. The tail of a horse is a very useful appendage; I have passed a river in a boat with four people in it, which was ferried across in the same way as the Gaucho. If a man and horse have to cross a broad river, the best plan is for the man to catch hold of the pommel or mane, and help himself with the other arm.

and thus lost much time. On a former excursion I crossed the Lucia near its mouth, and I was surprised to observe how easily our horses, although not used to swim, passed over a width of at least six hundred yards. On mentioning this at Monte Video, I was told that a vessel containing some mountebanks and their horses, being wrecked in the Plata, one horse swam seven miles to the shore. In the course of the day I was amused by the dexterity with which a Gaucho forced a restive horse to swim a river. He stripped off his clothes, and jumping on its back, rode into the water till it was out of its depth; then slipping off over the crupper, he caught hold of the tail, and as often as the horse turned round the man frightened it back by splashing water in its face. As soon as the horse touched the bottom on the other side, the man pulled himself on, and was firmly seated, bridle in hand, before the horse gained the bank. A naked man on a naked horse is a fine spectacle; I had no idea how well the two animals suited each other. The tail of a horse is a very useful appendage; I have passed a river in a boat with four people in it, which was ferried across in the same way as the Gaucho. If a man and horse have to cross a broad river, the best plan is for the man to catch hold of the pommel or mane, and help himself with the other arm.

We slept and stayed the following day at the post of Cufre.  In the evening the postman or letter-carrier arrived. He was a day after his time, owing to the Rio Rozario being flooded. It would not, however, be of much consequence; for, although he had passed through some of the principal towns in Banda Oriental, his luggage consisted of two letters! The view from the house was pleasing; an undulating green surface, with distant glimpses of the Plata. I find that I look at this province with very different eyes from what I did upon my first arrival. I recollect I then thought it singularly level; but now, after galloping over the Pampas, my only surprise is, what could have induced me ever to call it level. The country is a series of undulations, in themselves perhaps not absolutely great, but, as compared to the plains of St. Fe, real mountains. From these inequalities there is an abundance of small rivulets, and the turf is green and luxuriant.

In the evening the postman or letter-carrier arrived. He was a day after his time, owing to the Rio Rozario being flooded. It would not, however, be of much consequence; for, although he had passed through some of the principal towns in Banda Oriental, his luggage consisted of two letters! The view from the house was pleasing; an undulating green surface, with distant glimpses of the Plata. I find that I look at this province with very different eyes from what I did upon my first arrival. I recollect I then thought it singularly level; but now, after galloping over the Pampas, my only surprise is, what could have induced me ever to call it level. The country is a series of undulations, in themselves perhaps not absolutely great, but, as compared to the plains of St. Fe, real mountains. From these inequalities there is an abundance of small rivulets, and the turf is green and luxuriant.

November 17th.—We crossed the Rozario,  which was deep and rapid, and passing the village of Colla,

which was deep and rapid, and passing the village of Colla,  arrived at midday at Colonia del Sacramiento {sic, Sacramento}.

arrived at midday at Colonia del Sacramiento {sic, Sacramento}.  The distance is twenty leagues, through a country covered with fine grass, but poorly stocked with cattle or inhabitants. I was invited to sleep at Colonia, and to accompany on the following day a gentleman to his estancia, where there were some limestone rocks. The town is built on a stony promontory something in the same manner as at Monte Video. It is strongly fortified, but both fortifications and town suffered much in the Brazilian war. It is very ancient; and the irregularity of the streets, and the surrounding groves of old orange and peach trees, gave it a pretty appearance. The church is a curious ruin; it was used as a powder-magazine, and was struck by lightning in one of the ten thousand thunderstorms of the Rio Plata. Two-thirds of the building were blown away to the very foundation; and the rest stands a shattered and curious monument of the united powers of lightning and gunpowder. In the evening I wandered about the half-demolished walls of the town. It was the chief seat of the Brazilian war;—a war most injurious to this country, not so much in its immediate effects, as in being the origin of a multitude of generals and all other grades of officers. More generals are numbered (but not paid) in the United Provinces of La Plata than in the United Kingdom of Great Britain. These gentlemen have learned to like power, and do not object to a little skirmishing. Hence there are many always on the watch to create disturbance and to overturn a government which as yet has never rested on any staple {sic, stable} foundation. I noticed, however, both here and in other places, a very general interest in the ensuing election for the President; and this appears a good sign for the prosperity of this little country. The inhabitants do not require much education in their representatives; I heard some men discussing the merits of those for Colonia; and it was said that, “although they were not men of business, they could all sign their names:” with this they seemed to think every reasonable man ought to be satisfied.

The distance is twenty leagues, through a country covered with fine grass, but poorly stocked with cattle or inhabitants. I was invited to sleep at Colonia, and to accompany on the following day a gentleman to his estancia, where there were some limestone rocks. The town is built on a stony promontory something in the same manner as at Monte Video. It is strongly fortified, but both fortifications and town suffered much in the Brazilian war. It is very ancient; and the irregularity of the streets, and the surrounding groves of old orange and peach trees, gave it a pretty appearance. The church is a curious ruin; it was used as a powder-magazine, and was struck by lightning in one of the ten thousand thunderstorms of the Rio Plata. Two-thirds of the building were blown away to the very foundation; and the rest stands a shattered and curious monument of the united powers of lightning and gunpowder. In the evening I wandered about the half-demolished walls of the town. It was the chief seat of the Brazilian war;—a war most injurious to this country, not so much in its immediate effects, as in being the origin of a multitude of generals and all other grades of officers. More generals are numbered (but not paid) in the United Provinces of La Plata than in the United Kingdom of Great Britain. These gentlemen have learned to like power, and do not object to a little skirmishing. Hence there are many always on the watch to create disturbance and to overturn a government which as yet has never rested on any staple {sic, stable} foundation. I noticed, however, both here and in other places, a very general interest in the ensuing election for the President; and this appears a good sign for the prosperity of this little country. The inhabitants do not require much education in their representatives; I heard some men discussing the merits of those for Colonia; and it was said that, “although they were not men of business, they could all sign their names:” with this they seemed to think every reasonable man ought to be satisfied.

18th.—Rode with my host to his estancia, at the Arroyo de San Juan.  In the evening we took a ride round the estate: it contained two square leagues and a half, and was situated in what is called a rincon; that is, one side was fronted by the Plata, and the two others guarded by impassable brooks.§ There was an excellent port for little vessels, and an abundance of small wood, which is valuable as supplying fuel to Buenos Ayres. I was curious to know the value of so complete an estancia. Of cattle there were 3000, and it would well support three or four times that number; of mares 800, together with 150 broken-in horses, and 600 sheep. There was plenty of water and limestone, a rough house, excellent corrals, and a peach orchard. For all this he had been offered 2000 Pounds, and he only wanted 500 Pounds additional, and probably would sell it for less. The chief trouble with an estancia is driving the cattle twice a week to a central spot, in order to make them tame, and to count them. This latter operation would be thought difficult, where there are ten or fifteen thousand head together. It is managed on the principle that the cattle invariably divide themselves into little troops of from forty to one hundred. Each troop is recognized by a few peculiarly marked animals, and its number is known: so that, one being lost out of ten thousand, it is perceived by its absence from one of the tropillas. During a stormy night the cattle all mingle together; but the next morning the tropillas separate as before; so that each animal must know its fellow out of ten thousand others.

In the evening we took a ride round the estate: it contained two square leagues and a half, and was situated in what is called a rincon; that is, one side was fronted by the Plata, and the two others guarded by impassable brooks.§ There was an excellent port for little vessels, and an abundance of small wood, which is valuable as supplying fuel to Buenos Ayres. I was curious to know the value of so complete an estancia. Of cattle there were 3000, and it would well support three or four times that number; of mares 800, together with 150 broken-in horses, and 600 sheep. There was plenty of water and limestone, a rough house, excellent corrals, and a peach orchard. For all this he had been offered 2000 Pounds, and he only wanted 500 Pounds additional, and probably would sell it for less. The chief trouble with an estancia is driving the cattle twice a week to a central spot, in order to make them tame, and to count them. This latter operation would be thought difficult, where there are ten or fifteen thousand head together. It is managed on the principle that the cattle invariably divide themselves into little troops of from forty to one hundred. Each troop is recognized by a few peculiarly marked animals, and its number is known: so that, one being lost out of ten thousand, it is perceived by its absence from one of the tropillas. During a stormy night the cattle all mingle together; but the next morning the tropillas separate as before; so that each animal must know its fellow out of ten thousand others.

§ In the Google Earth 3D view, note two brooks, one north (Rio San Juan), the other south (Arroyo San Pedro), of Arroyo de San Juan.

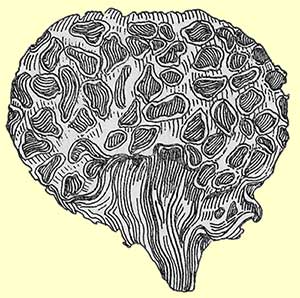

On two occasions I met with in this province some oxen of a very curious breed, called nata or niata. They appear externally to hold nearly the same relation to other cattle, which bull or pug dogs do to other dogs. Their forehead is very short and broad, with the nasal end turned up, and the upper lip much drawn back; their lower jaws project beyond the upper, and have a corresponding upward curve; hence their teeth are always exposed. Their nostrils are seated high up and are very open; their eyes project outwards. When walking they carry their heads low, on a short neck; and their hinder legs are rather longer compared with the front legs than is usual. Their bare teeth, their short heads, and upturned nostrils give them the most ludicrous self-confident air of defiance imaginable.

Since my return, I have procured a skeleton head, through the kindness of my friend Captain Sulivan, R. N., which is now deposited in the College of Surgeons.* Don F. Muniz, of Luxan, has kindly collected for me all the information which he could respecting this breed. From his account it seems that about eighty or ninety years ago, they were rare and kept as curiosities at Buenos Ayres. The breed is universally believed to have originated amongst the Indians southward of the Plata; and that it was with them the commonest kind. Even to this day, those reared in the provinces near the Plata show their less civilized origin, in being fiercer than common cattle, and in the cow easily deserting her first calf, if visited too often or molested. It is a singular fact that an almost similar structure to the abnormal † one of the niata breed, characterizes, as I am informed by Dr. Falconer,§ that great extinct ruminant of India, the Sivatherium. The breed is very true; and a niata bull and cow invariably produce niata calves. A niata bull with a common cow, or the reverse cross, produces offspring having an intermediate character, but with the niata characters strongly displayed: according to Senor Muniz, there is the clearest evidence, contrary to the common belief of agriculturists in analogous cases, that the niata cow when crossed with a common bull transmits her peculiarities more strongly than the niata bull when crossed with a common cow. When the pasture is tolerably long, the niata cattle feed with the tongue and palate as well as common cattle; but during the great droughts, when so many animals perish, the niata breed is under a great disadvantage, and would be exterminated if not attended to; for the common cattle, like horses, are able just to keep alive, by browsing with their lips on twigs of trees and reeds; this the niatas cannot so well do, as their lips do not join, and hence they are found to perish before the common cattle. This strikes me as a good illustration of how little we are able to judge from the ordinary habits of life, on what circumstances, occurring only at long intervals, the rarity or extinction of a species may be determined.

* Mr. Waterhouse has drawn up a detailed description of this head, which I hope he will publish in some Journal.

† A nearly similar abnormal, but I do not know whether hereditary, structure has been observed in the carp, and likewise in the crocodile of the Ganges: Histoire des Anomalies, par M. Isid. Geoffroy St. Hilaire, tom. i. p. 244.

§ In this case, Dr. Hugh Falconer. Darwin's other “Falconer” citations in Part 1 refer to Thomas Falkner, S. J.

November 19th.—Passing the valley of Las Vacas,  we slept at a house of a North American, who worked a lime-kiln on the Arroyo de las Vivoras. In the morning we rode to a protecting headland on the banks of the river, called Punta Gorda.

we slept at a house of a North American, who worked a lime-kiln on the Arroyo de las Vivoras. In the morning we rode to a protecting headland on the banks of the river, called Punta Gorda.  On the way we tried to find a jaguar. There were plenty of fresh tracks, and we visited the trees, on which they are said to sharpen their claws; but we did not succeed in disturbing one. From this point the Rio Uruguay presented to our view a noble volume of water. From the clearness and rapidity of the stream, its appearance was far superior to that of its neighbour the Parana. On the opposite coast, several branches from the latter river entered the Uruguay. As the sun was shining, the two colours of the waters could be seen quite distinct.

On the way we tried to find a jaguar. There were plenty of fresh tracks, and we visited the trees, on which they are said to sharpen their claws; but we did not succeed in disturbing one. From this point the Rio Uruguay presented to our view a noble volume of water. From the clearness and rapidity of the stream, its appearance was far superior to that of its neighbour the Parana. On the opposite coast, several branches from the latter river entered the Uruguay. As the sun was shining, the two colours of the waters could be seen quite distinct.

In the evening we proceeded on our road towards Mercedes  on the Rio Negro. At night we asked permission to sleep at an estancia at which we happened to arrive. It was a very large estate, being ten leagues square, and the owner is one of the greatest landowners in the country. His nephew had charge of it, and with him there was a captain in the army, who the other day ran away from Buenos Ayres. Considering their station, their conversation was rather amusing. They expressed, as was usual, unbounded astonishment at the globe being round, and could scarcely credit that a hole would, if deep enough, come out on the other side. They had, however, heard of a country where there were six months of light and six of darkness, and where the inhabitants were very tall and thin! They were curious about the price and condition of horses and cattle in England. Upon finding out we did not catch our animals with the lazo, they cried out, “Ah, then, you use nothing but the bolas:” the idea of an enclosed country was quite new to them. The captain at last said, he had one question to ask me, which he should be very much obliged if I would answer with all truth. I trembled to think how deeply scientific it would be: it was, “Whether the ladies of Buenos Ayres were not the handsomest in the world.” I replied, like a renegade, “Charmingly so.” He added, “I have one other question: Do ladies in any other part of the world wear such large combs?” I solemnly assured him that they did not. They were absolutely delighted. The captain exclaimed, “Look there! a man who has seen half the world says it is the case; we always thought so, but now we know it.” My excellent judgment in combs and beauty procured me a most hospitable reception; the captain forced me to take his bed, and he would sleep on his recado.

on the Rio Negro. At night we asked permission to sleep at an estancia at which we happened to arrive. It was a very large estate, being ten leagues square, and the owner is one of the greatest landowners in the country. His nephew had charge of it, and with him there was a captain in the army, who the other day ran away from Buenos Ayres. Considering their station, their conversation was rather amusing. They expressed, as was usual, unbounded astonishment at the globe being round, and could scarcely credit that a hole would, if deep enough, come out on the other side. They had, however, heard of a country where there were six months of light and six of darkness, and where the inhabitants were very tall and thin! They were curious about the price and condition of horses and cattle in England. Upon finding out we did not catch our animals with the lazo, they cried out, “Ah, then, you use nothing but the bolas:” the idea of an enclosed country was quite new to them. The captain at last said, he had one question to ask me, which he should be very much obliged if I would answer with all truth. I trembled to think how deeply scientific it would be: it was, “Whether the ladies of Buenos Ayres were not the handsomest in the world.” I replied, like a renegade, “Charmingly so.” He added, “I have one other question: Do ladies in any other part of the world wear such large combs?” I solemnly assured him that they did not. They were absolutely delighted. The captain exclaimed, “Look there! a man who has seen half the world says it is the case; we always thought so, but now we know it.” My excellent judgment in combs and beauty procured me a most hospitable reception; the captain forced me to take his bed, and he would sleep on his recado.

21st.—Started at sunrise, and rode slowly during the whole day. The geological nature of this part of the province was different from the rest, and closely resembled that of the Pampas. In consequence, there were immense beds of the thistle, as well as of the cardoon: the whole country, indeed, may be called one great bed of these plants. The two sorts grow separate, each plant in company with its own kind. The cardoon is as high as a horse's back, but the Pampas thistle is often higher than the crown of the rider's head. To leave the road for a yard is out of the question; and the road itself is partly, and in some cases entirely closed. Pasture, of course there is none; if cattle or horses once enter the bed, they are for the time completely lost. Hence it is very hazardous to attempt to drive cattle at this season of the year; for when jaded enough to face the thistles, they rush among them, and are seen no more. In these districts there are very few estancias, and these few are situated in the neighbourhood of damp valleys, where fortunately neither of these overwhelming plants can exist. As night came on before we arrived at our journey's end, we slept at a miserable little hovel inhabited by the poorest people. The extreme though rather formal courtesy of our host and hostess, considering their grade of life, was quite delightful.

November 22nd.—Arrived at an estancia on the Berquelo {sic, Rio Bequelo}  belonging to a very hospitable Englishman, to whom I had a letter of introduction from my friend Mr. Lumb. I stayed here three days. One morning I rode with my host to the Sierra del Pedro {sic, Perico} Flaco,

belonging to a very hospitable Englishman, to whom I had a letter of introduction from my friend Mr. Lumb. I stayed here three days. One morning I rode with my host to the Sierra del Pedro {sic, Perico} Flaco,  about twenty miles up the Rio Negro. Nearly the whole country was covered with good though coarse grass, which was as high as a horse's belly; yet there were square leagues without a single head of cattle. The province of Banda Oriental, if well stocked, would support an astonishing number of animals, at present the annual export of hides from Monte Video amounts to three hundred thousand; and the home consumption, from waste, is very considerable. An “estanciero” told me that he often had to send large herds of cattle a long journey to a salting establishment, and that the tired beasts were frequently obliged to be killed and skinned; but that he could never persuade the Gauchos to eat of them, and every evening a fresh beast was slaughtered for their suppers! The view of the Rio Negro from the Sierra was more picturesque than any other which I saw in this province. The river, broad, deep, and rapid, wound at the foot of a rocky precipitous cliff: a belt of wood followed its course, and the horizon terminated in the distant undulations of the turf-plain.

about twenty miles up the Rio Negro. Nearly the whole country was covered with good though coarse grass, which was as high as a horse's belly; yet there were square leagues without a single head of cattle. The province of Banda Oriental, if well stocked, would support an astonishing number of animals, at present the annual export of hides from Monte Video amounts to three hundred thousand; and the home consumption, from waste, is very considerable. An “estanciero” told me that he often had to send large herds of cattle a long journey to a salting establishment, and that the tired beasts were frequently obliged to be killed and skinned; but that he could never persuade the Gauchos to eat of them, and every evening a fresh beast was slaughtered for their suppers! The view of the Rio Negro from the Sierra was more picturesque than any other which I saw in this province. The river, broad, deep, and rapid, wound at the foot of a rocky precipitous cliff: a belt of wood followed its course, and the horizon terminated in the distant undulations of the turf-plain.

When in this neighbourhood, I several times heard of the Sierra de las Cuentas: a hill distant many miles to the northward. The name signifies hill of beads. I was assured that vast numbers of little round stones, of various colours, each with a small cylindrical hole, are found there. Formerly the Indians used to collect them, for the purpose of making necklaces and bracelets—a taste, I may observe, which is common to all savage nations, as well as to the most polished. I did not know what to understand from this story, but upon mentioning it at the Cape of Good Hope to Dr. Andrew Smith, he told me that he recollected finding on the south-eastern coast of Africa, about one hundred miles to the eastward of St. John's river, some quartz crystals with their edges blunted from attrition, and mixed with gravel on the sea-beach. Each crystal was about five lines in diameter, and from an inch to an inch and a half in length. Many of them had a small canal extending from one extremity to the other, perfectly cylindrical, and of a size that readily admitted a coarse thread or a piece of fine catgut. Their colour was red or dull white. The natives were acquainted with this structure in crystals. I have mentioned these circumstances because, although no crystallized body is at present known to assume this form, it may lead some future traveller to investigate the real nature of such stones.

While staying at this estancia, I was amused with what I saw and heard of the shepherd-dogs of the country.* When riding, it is a common thing to meet a large flock of sheep guarded by one or two dogs, at the distance of some miles from any house or man. I often wondered how so firm a friendship had been established. The method of education consists in separating the puppy, while very young, from the bitch, and in accustoming it to its future companions. An ewe is held three or four times a day for the little thing to suck, and a nest of wool is made for it in the sheep-pen; at no time is it allowed to associate with other dogs, or with the children of the family. The puppy is, moreover, generally castrated; so that, when grown up, it can scarcely have any feelings in common with the rest of its kind. From this education it has no wish to leave the flock, and just as another dog will defend its master, man, so will these the sheep. It is amusing to observe, when approaching a flock, how the dog immediately advances barking, and the sheep all close in his rear, as if round the oldest ram. These dogs are also easily taught to bring home the flock, at a certain hour in the evening. Their most troublesome fault, when young, is their desire of playing with the sheep; for in their sport they sometimes gallop their poor subjects most unmercifully.

* M. A. d'Orbigny has given nearly a similar account of these dogs, tom. i. p. 175.

The shepherd-dog comes to the house every day for some meat, and as soon as it is given him, he skulks away as if ashamed of himself. On these occasions the house-dogs are very tyrannical, and the least of them will attack and pursue the stranger. The minute, however, the latter has reached the flock, he turns round and begins to bark, and then all the house-dogs take very quickly to their heels. In a similar manner a whole pack of the hungry wild dogs will scarcely ever (and I was told by some never) venture to attack a flock guarded by even one of these faithful shepherds. The whole account appears to me a curious instance of the pliability of the affections in the dog; and yet, whether wild or however educated, he has a feeling of respect or fear for those that are fulfilling their instinct of association. For we can understand on no principle the wild dogs being driven away by the single one with its flock, except that they consider, from some confused notion, that the one thus associated gains power, as if in company with its own kind. F. Cuvier has observed that all animals that readily enter into domestication, consider man as a member of their own society, and thus fulfil their instinct of association. In the above case the shepherd-dog ranks the sheep as its fellow-brethren, and thus gains confidence; and the wild dogs, though knowing that the individual sheep are not dogs, but are good to eat, yet partly consent to this view when seeing them in a flock with a shepherd-dog at their head.

One evening a “domidor” (a subduer of horses) came for the purpose of breaking-in some colts. I will describe the preparatory steps, for I believe they have not been mentioned by other travellers. A troop of wild young horses is driven into the corral, or large enclosure of stakes, and the door is shut. We will suppose that one man alone has to catch and mount a horse, which as yet had never felt bridle or saddle. I conceive, except by a Gaucho, such a feat would be utterly impracticable. The Gaucho picks out a full-grown colt; and as the beast rushes round the circus he throws his lazo so as to catch both the front legs. Instantly the horse rolls over with a heavy shock, and whilst struggling on the ground, the Gaucho, holding the lazo tight, makes a circle, so as to catch one of the hind legs just beneath the fetlock, and draws it close to the two front legs: he then hitches the lazo, so that the three are bound together. Then sitting on the horse's neck, he fixes a strong bridle, without a bit, to the lower jaw: this he does by passing a narrow thong through the eye-holes at the end of the reins, and several times round both jaw and tongue. The two front legs are now tied closely together with a strong leathern thong, fastened by a slip-knot. The lazo, which bound the three together, being then loosed, the horse rises with difficulty. The Gaucho now holding fast the bridle fixed to the lower jaw, leads the horse outside the corral. If a second man is present (otherwise the trouble is much greater) he holds the animal's head, whilst the first puts on the horsecloths and saddle, and girths the whole together. During this operation, the horse, from dread and astonishment at thus being bound round the waist, throws himself over and over again on the ground, and, till beaten, is unwilling to rise. At last, when the saddling is finished, the poor animal can hardly breathe from fear, and is white with foam and sweat. The man now prepares to mount by pressing heavily on the stirrup, so that the horse may not lose its balance; and at the moment that he throws his leg over the animal's back, he pulls the slip-knot binding the front legs, and the beast is free. Some “domidors” pull the knot while the animal is lying on the ground, and, standing over the saddle, allow him to rise beneath them. The horse, wild with dread, gives a few most violent bounds, and then starts off at full gallop: when quite exhausted, the man, by patience, brings him back to the corral, where, reeking hot and scarcely alive, the poor beast is let free. Those animals which will not gallop away, but obstinately throw themselves on the ground, are by far the most troublesome. This process is tremendously severe, but in two or three trials the horse is tamed. It is not, however, for some weeks that the animal is ridden with the iron bit and solid ring, for it must learn to associate the will of its rider with the feel of the rein, before the most powerful bridle can be of any service.

Animals are so abundant in these countries, that humanity and self-interest are not closely united; therefore I fear it is that the former is here scarcely known. One day, riding in the Pampas with a very respectable “estanciero” my horse, being tired, lagged behind. The man often shouted to me to spur him. When I remonstrated that it was a pity, for the horse was quite exhausted, he cried out, “Why not?—never mind—spur him—it is my horse.” I had then some difficulty in making him comprehend that it was for the horse's sake, and not on his account, that I did not choose to use my spurs. He exclaimed, with a look of great surprise, “Ah, Don Carlos, que cosa!” It was clear that such an idea had never before entered his head.

The Gauchos are well known to be perfect riders. The idea of being thrown, let the horse do what it likes; never enters their head. Their criterion of a good rider is, a man who can manage an untamed colt, or who, if his horse falls, alights on his own feet, or can perform other such exploits. I have heard of a man betting that he would throw his horse down twenty times, and that nineteen times he would not fall himself. I recollect seeing a Gaucho riding a very stubborn horse, which three times successively reared so high as to fall backwards with great violence. The man judged with uncommon coolness the proper moment for slipping off, not an instant before or after the right time; and as soon as the horse got up, the man jumped on his back, and at last they started at a gallop. The Gaucho never appears to exert any muscular force. I was one day watching a good rider, as we were galloping along at a rapid pace, and thought to myself, “Surely if the horse starts, you appear so careless on your seat, you must fall.” At this moment, a male ostrich sprang from its nest right beneath the horse's nose: the young colt bounded on one side like a stag; but as for the man, all that could be said was, that he started and took fright with his horse.

In Chile and Peru more pains are taken with the mouth of the horse than in La Plata, and this is evidently a consequence of the more intricate nature of the country. In Chile a horse is not considered perfectly broken, till he can be brought up standing, in the midst of his full speed, on any particular spot,—for instance, on a cloak thrown on the ground: or, again, he will charge a wall, and rearing, scrape the surface with his hoofs. I have seen an animal bounding with spirit, yet merely reined by a fore-finger and thumb, taken at full gallop across a courtyard, and then made to wheel round the post of a veranda with great speed, but at so equal a distance, that the rider, with outstretched arm, all the while kept one finger rubbing the post. Then making a demi-volte in the air, with the other arm outstretched in a like manner, he wheeled round, with astonishing force, in an opposite direction.

Such a horse is well broken; and although this at first may appear useless, it is far otherwise. It is only carrying that which is daily necessary into perfection. When a bullock is checked and caught by the lazo, it will sometimes gallop round and round in a circle, and the horse being alarmed at the great strain, if not well broken, will not readily turn like the pivot of a wheel. In consequence many men have been killed; for if the lazo once takes a twist round a man's body, it will instantly, from the power of the two opposed animals, almost cut him in twain. On the same principle the races are managed; the course is only two or three hundred yards long, the wish being to have horses that can make a rapid dash. The race-horses are trained not only to stand with their hoofs touching a line, but to draw all four feet together, so as at the first spring to bring into play the full action of the hind-quarters. In Chile I was told an anecdote, which I believe was true; and it offers a good illustration of the use of a well-broken animal. A respectable man riding one day met two others, one of whom was mounted on a horse, which he knew to have been stolen from himself. He challenged them; they answered him by drawing their sabres and giving chase. The man, on his good and fleet beast, kept just ahead: as he passed a thick bush he wheeled round it, and brought up his horse to a dead check. The pursuers were obliged to shoot on one side and ahead. Then instantly dashing on, right behind them, he buried his knife in the back of one, wounded the other, recovered his horse from the dying robber, and rode home. For these feats of horsemanship two things are necessary: a most severe bit, like the Mameluke, the power of which, though seldom used, the horse knows full well; and large blunt spurs, that can be applied either as a mere touch, or as an instrument of extreme pain. I conceive that with English spurs, the slightest touch of which pricks the skin, it would be impossible to break in a horse after the South American fashion.

At an estancia near Las Vacas large numbers of mares are weekly slaughtered for the sake of their hides, although worth only five paper dollars, or about half a crown apiece. It seems at first strange that it can answer to kill mares for such a trifle; but as it is thought ridiculous in this country ever to break in or ride a mare, they are of no value except for breeding. The only thing for which I ever saw mares used, was to tread out wheat from the ear, for which purpose they were driven round a circular enclosure, where the wheat-sheaves were strewed. The man employed for slaughtering the mares happened to be celebrated for his dexterity with the lazo. Standing at the distance of twelve yards from the mouth of the corral, he has laid a wager that he would catch by the legs every animal, without missing one, as it rushed past him. There was another man who said he would enter the corral on foot, catch a mare, fasten her front legs together, drive her out, throw her down, kill, skin, and stake the hide for drying (which latter is a tedious job); and he engaged that he would perform this whole operation on twenty-two animals in one day. Or he would kill and take the skin off fifty in the same time. This would have been a prodigious task, for it is considered a good day's work to skin and stake the hides of fifteen or sixteen animals.

November 26th.—I set out on my return in a direct line for Monte Video. Having heard of some giant's bones at a neighbouring farm-house on the Sarandis, {sic, Sarandí}  a small stream entering the Rio Negro, I rode there accompanied by my host, and purchased for the value of eighteen pence the head of the Toxodon.* When found it was quite perfect; but the boys knocked out some of the teeth with stones, and then set up the head as a mark to throw at. By a most fortunate chance I found a perfect tooth, which exactly fitted one of the sockets in this skull, embedded by itself on the banks of the Rio Tercero,§ at the distance of about 180 miles from this place. I found remains of this extraordinary animal at two other places, so that it must formerly have been common. I found here, also, some large portions of the armour of a gigantic armadillo-like animal, and part of the great head of a Mylodon. The bones of this head are so fresh, that they contain, according to the analysis by Mr. T. Reeks, seven per cent of animal matter; and when placed in a spirit-lamp, they burn with a small flame. The number of the remains embedded in the grand estuary deposit which forms the Pampas and covers the granitic rocks of Banda Oriental, must be extraordinarily great. I believe a straight line drawn in any direction through the Pampas would cut through some skeleton or bones. Besides those which I found during my short excursions, I heard of many others, and the origin of such names as “the stream of the animal” “the hill of the giant” is obvious. At other times I heard of the marvellous property of certain rivers, which had the power of changing small bones into large; or, as some maintained, the bones themselves grew. As far as I am aware, not one of these animals perished, as was formerly supposed, in the marshes or muddy river-beds of the present land, but their bones have been exposed by the streams intersecting the subaqueous deposit in which they were originally embedded. We may conclude that the whole area of the Pampas is one wide sepulchre of these extinct gigantic quadrupeds.

a small stream entering the Rio Negro, I rode there accompanied by my host, and purchased for the value of eighteen pence the head of the Toxodon.* When found it was quite perfect; but the boys knocked out some of the teeth with stones, and then set up the head as a mark to throw at. By a most fortunate chance I found a perfect tooth, which exactly fitted one of the sockets in this skull, embedded by itself on the banks of the Rio Tercero,§ at the distance of about 180 miles from this place. I found remains of this extraordinary animal at two other places, so that it must formerly have been common. I found here, also, some large portions of the armour of a gigantic armadillo-like animal, and part of the great head of a Mylodon. The bones of this head are so fresh, that they contain, according to the analysis by Mr. T. Reeks, seven per cent of animal matter; and when placed in a spirit-lamp, they burn with a small flame. The number of the remains embedded in the grand estuary deposit which forms the Pampas and covers the granitic rocks of Banda Oriental, must be extraordinarily great. I believe a straight line drawn in any direction through the Pampas would cut through some skeleton or bones. Besides those which I found during my short excursions, I heard of many others, and the origin of such names as “the stream of the animal” “the hill of the giant” is obvious. At other times I heard of the marvellous property of certain rivers, which had the power of changing small bones into large; or, as some maintained, the bones themselves grew. As far as I am aware, not one of these animals perished, as was formerly supposed, in the marshes or muddy river-beds of the present land, but their bones have been exposed by the streams intersecting the subaqueous deposit in which they were originally embedded. We may conclude that the whole area of the Pampas is one wide sepulchre of these extinct gigantic quadrupeds.

* I must express my obligations to Mr. Keane, at whose house I was staying on the Berquelo, and to Mr. Lumb at Buenos Ayres, for without their assistance these valuable remains would never have reached England.

§ Rio Tercero in Argentina {See October 1 entry}

By the middle of the day, on the 28th, we arrived at Monte Video, having been two days and a half on the road. The country for the whole way was of a very uniform character, some parts being rather more rocky and hilly than near the Plata. Not far from Monte Video we passed through the village of Las Pietras, {sic, Las Piedras}  so named from some large rounded masses of syenite. Its appearance was rather pretty. In this country a few fig-trees round a group of houses, and a site elevated a hundred feet above the general level, ought always to be called picturesque.

so named from some large rounded masses of syenite. Its appearance was rather pretty. In this country a few fig-trees round a group of houses, and a site elevated a hundred feet above the general level, ought always to be called picturesque.

During the last six months I have had an opportunity of seeing a little of the character of the inhabitants of these provinces. The Gauchos, or countryrmen, are very superior to those who reside in the towns. The Gaucho is invariably most obliging, polite, and hospitable: I did not meet with even one instance of rudeness or inhospitality. He is modest, both respecting himself and country, but at the same time a spirited, bold fellow. On the other hand, many robberies are committed, and there is much bloodshed: the habit of constantly wearing the knife is the chief cause of the latter. It is lamentable to hear how many lives are lost in trifling quarrels. In fighting, each party tries to mark the face of his adversary by slashing his nose or eyes; as is often attested by deep and horrid-looking scars. Robberies are a natural consequence of universal gambling, much drinking, and extreme indolence. At Mercedes I asked two men why they did not work. One gravely said the days were too long; the other that he was too poor. The number of horses and the profusion of food are the destruction of all industry. Moreover, there are so many feast-days; and again, nothing can succeed without it be begun when the moon is on the increase; so that half the month is lost from these two causes.

Police and justice are quite inefficient. If a man who is poor commits murder and is taken, he will be imprisoned, and perhaps even shot; but if he is rich and has friends, he may rely on it no very severe consequence will ensue. It is curious that the most respectable inhabitants of the country invariably assist a murderer to escape: they seem to think that the individual sins against the government, and not against the people. A traveller has no protection besides his fire-arms; and the constant habit of carrying them is the main check to more frequent robberies. The character of the higher and more educated classes who reside in the towns, partakes, but perhaps in a lesser degree, of the good parts of the Gaucho, but is, I fear, stained by many vices of which he is free. Sensuality, mockery of all religion, and the grossest corruption, are far from uncommon. Nearly every public officer can be bribed. The head man in the post-office sold forged government franks. The governor and prime minister openly combined to plunder the state. Justice, where gold came into play, was hardly expected by any one. I knew an Englishman, who went to the Chief Justice (he told me, that not then understanding the ways of the place, he trembled as he entered the room), and said,“Sir, I have come to offer you two hundred (paper) dollars (value about five pounds sterling) if you will arrest before a certain time a man who has cheated me. I know it is against the law, but my lawyer (naming him) recommended me to take this step.” The Chief Justice smiled acquiescence, thanked him, and the man before night was safe in prison. With this entire want of principle in many of the leading men, with the country full of ill-paid turbulent officers, the people yet hope that a democratic form of government can succeed!

On first entering society in these countries, two or three features strike one as particularly remarkable. The polite and dignified manners pervading every rank of life, the excellent taste displayed by the women in their dresses, and the equality amongst all ranks. At the Rio Colorado some men who kept the humblest shops used to dine with General Rosas. A son of a major at Bahia Blanca gained his livelihood by making paper cigars, and he wished to accompany me, as guide or servant, to Buenos Ayres, but his father objected on the score of the danger alone. Many officers in the army can neither read nor write, yet all meet in society as equals. In Entre Rios, the Sala consisted of only six representatives. One of them kept a common shop, and evidently was not degraded by the office. All this is what would be expected in a new country; nevertheless the absence of gentlemen by profession appears to an Englishman something strange.

When speaking of these countries, the manner in which they have been brought up by their unnatural parent, Spain, should always be borne in mind. On the whole, perhaps, more credit is due for what has been done, than blame for that which may be deficient. It is impossible to doubt but that the extreme liberalism of these countries must ultimately lead to good results. The very general toleration of foreign religions, the regard paid to the means of education, the freedom of the press, the facilities offered to all foreigners, and especially, as I am bound to add, to every one professing the humblest pretensions to science, should be recollected with gratitude by those who have visited Spanish South America.

December 6th.—The Beagle sailed from the Rio Plata, never again to enter its muddy stream. Our course was directed to Port Desire, on the coast of Patagonia. Before proceeding any further, I will here put together a few observations made at sea.

Several times when the ship has been some miles off the mouth of the Plata, and at other times when off the shores of Northern Patagonia, we have been surrounded by insects. One evening, when we were about ten miles from the Bay of San Blas,  vast numbers of butterflies, in bands or flocks of countless myriads, extended as far as the eye could range. Even by the aid of a telescope it was not possible to see a space free from butterflies. The seamen cried out “it was snowing butterflies” and such in fact was the appearance. More species than one were present, but the main part belonged to a kind very similar to, but not identical with, the common English Colias edusa. Some moths and hymenoptera accompanied the butterflies; and a fine beetle (Calosoma) flew on board. Other instances are known of this beetle having been caught far out at sea; and this is the more remarkable, as the greater number of the Carabidae seldom or never take wing. The day had been fine and calm, and the one previous to it equally so, with light and variable airs. Hence we cannot suppose that the insects were blown off the land, but we must conclude that they voluntarily took flight. The great bands of the Colias seem at first to afford an instance like those on record of the migrations of another butterfly, Vanessa cardui;* but the presence of other insects makes the case distinct, and even less intelligible. Before sunset a strong breeze sprung up from the north, and this must have caused tens of thousands of the butterflies and other insects to have perished.

vast numbers of butterflies, in bands or flocks of countless myriads, extended as far as the eye could range. Even by the aid of a telescope it was not possible to see a space free from butterflies. The seamen cried out “it was snowing butterflies” and such in fact was the appearance. More species than one were present, but the main part belonged to a kind very similar to, but not identical with, the common English Colias edusa. Some moths and hymenoptera accompanied the butterflies; and a fine beetle (Calosoma) flew on board. Other instances are known of this beetle having been caught far out at sea; and this is the more remarkable, as the greater number of the Carabidae seldom or never take wing. The day had been fine and calm, and the one previous to it equally so, with light and variable airs. Hence we cannot suppose that the insects were blown off the land, but we must conclude that they voluntarily took flight. The great bands of the Colias seem at first to afford an instance like those on record of the migrations of another butterfly, Vanessa cardui;* but the presence of other insects makes the case distinct, and even less intelligible. Before sunset a strong breeze sprung up from the north, and this must have caused tens of thousands of the butterflies and other insects to have perished.

* Lyell's Principles of Geology, vol. iii. p. 63.

On another occasion, when seventeen miles off Cape Corrientes, I had a net overboard to catch pelagic animals. Upon drawing it up, to my surprise, I found a considerable number of beetles in it, and although in the open sea, they did not appear much injured by the salt water. I lost some of the specimens, but those which I preserved belonged to the genera Colymbetes, Hydroporus, Hydrobius (two species), Notaphus, Cynucus, Adimonia, and Scarabaeus. At first I thought that these insects had been blown from the shore; but upon reflecting that out of the eight species four were aquatic, and two others partly so in their habits, it appeared to me most probable that they were floated into the sea by a small stream which drains a lake near Cape Corrientes. On any supposition it is an interesting circumstance to find live insects swimming in the open ocean seventeen miles from the nearest point of land. There are several accounts of insects having been blown off the Patagonian shore. Captain Cook observed it, as did more lately Captain King of the Adventure. The cause probably is due to the want of shelter, both of trees and hills, so that an insect on the wing with an off-shore breeze, would be very apt to be blown out to sea. The most remarkable instance I have known of an insect being caught far from the land, was that of a large grasshopper (Acrydium), which flew on board, when the Beagle was to windward of the Cape de Verd Islands, {east of St. Jago} and when the nearest point of land, not directly opposed to the trade-wind, was Cape Blanco on the coast of Africa, 370 miles distant.*

* The flies which frequently accompany a ship for some days on its passage from harbour to harbour, wandering from the vessel, are soon lost, and all disappear.

On several occasions, when the Beagle has been within the mouth of the Plata, the rigging has been coated with the web of the Gossamer Spider. One day (November 1st, 1832) I paid particular attention to this subject. The weather had been fine and clear, and in the morning the air was full of patches of the flocculent web, as on an autumnal day in England. The ship was sixty miles distant from the land, in the direction of a steady though light breeze. Vast numbers of a small spider, about one-tenth of an inch in length, and of a dusky red colour, were attached to the webs. There must have been, I should suppose, some thousands on the ship. The little spider, when first coming in contact with the rigging, was always seated on a single thread, and not on the flocculent mass. This latter seems merely to be produced by the entanglement of the single threads. The spiders were all of one species, but of both sexes, together with young ones. These latter were distinguished by their smaller size and more dusky colour. I will not give the description of this spider, but merely state that it does not appear to me to be included in any of Latreille's genera. The little aeronaut as soon as it arrived on board was very active, running about, sometimes letting itself fall, and then reascending the same thread; sometimes employing itself in making a small and very irregular mesh in the corners between the ropes. It could run with facility on the surface of the water. When disturbed it lifted up its front legs, in the attitude of attention. On its first arrival it appeared very thirsty, and with exserted maxillae drank eagerly of drops of water, this same circumstance has been observed by Strack: may it not be in consequence of the little insect having passed through a dry and rarefied atmosphere? Its stock of web seemed inexhaustible. While watching some that were suspended by a single thread, I several times observed that the slightest breath of air bore them away out of sight, in a horizontal line.

On another occasion (25th) under similar circumstances, I repeatedly observed the same kind of small spider, either when placed or having crawled on some little eminence, elevate its abdomen, send forth a thread, and then sail away horizontally, but with a rapidity which was quite unaccountable. I thought I could perceive that the spider, before performing the above preparatory steps, connected its legs together with the most delicate threads, but I am not sure whether this observation was correct.

One day, at St. Fe, I had a better opportunity of observing some similar facts. A spider which was about three-tenths of an inch in length, and which in its general appearance resembled a Citigrade (therefore quite different from the gossamer), while standing on the summit of a post, darted forth four or five threads from its spinners. These, glittering in the sunshine, might be compared to diverging rays of light; they were not, however, straight, but in undulations like films of silk blown by the wind. They were more than a yard in length, and diverged in an ascending direction from the orifices. The spider then suddenly let go its hold of the post, and was quickly borne out of sight. The day was hot and apparently calm; yet under such circumstances, the atmosphere can never be so tranquil as not to affect a vane so delicate as the thread of a spider's web. If during a warm day we look either at the shadow of any object cast on a bank, or over a level plain at a distant landmark, the effect of an ascending current of heated air is almost always evident: such upward currents, it has been remarked, are also shown by the ascent of soap-bubbles, which will not rise in an in-doors room. Hence I think there is not much difficulty in understanding the ascent of the fine lines projected from a spider's spinners, and afterwards of the spider itself; the divergence of the lines has been attempted to be explained, I believe by Mr. Murray, by their similar electrical condition. The circumstance of spiders of the same species, but of different sexes and ages, being found on several occasions at the distance of many leagues from the land, attached in vast numbers to the lines, renders it probable that the habit of sailing through the air is as characteristic of this tribe, as that of diving is of the Argyroneta. We may then reject Latreille's supposition, that the gossamer owes its origin indifferently to the young of several genera of spiders: although, as we have seen, the young of other spiders do possess the power of performing aerial voyages.*

* Mr. Blackwall, in his Researches in Zoology, has many excellent observations on the habits of spiders.

During our different passages south of the Plata, I often towed astern a net made of bunting, and thus caught many curious animals. Of Crustacea there were many strange and undescribed genera. One, which in some respects is allied to the Notopods (or those crabs which have their posterior legs placed almost on their backs, for the purpose of adhering to the under side of rocks), is very remarkable from the structure of its hind pair of legs. The penultimate joint, instead of terminating in a simple claw, ends in three bristle-like appendages of dissimilar lengths—the longest equalling that of the entire leg. These claws are very thin, and are serrated with the finest teeth, directed backwards: their curved extremities are flattened, and on this part five most minute cups are placed which seem to act in the same manner as the suckers on the arms of the cuttle-fish. As the animal lives in the open sea, and probably wants a place of rest, I suppose this beautiful and most anomalous structure is adapted to take hold of floating marine animals.

In deep water, far from the land, the number of living creatures is extremely small: south of the latitude 35°, I never succeeded in catching anything besides some beroe, and a few species of minute entomostracous crustacea. In shoaler water, at the distance of a few miles from the coast, very many kinds of crustacea and some other animals are numerous, but only during the night. Between latitudes 56 and 57° south of Cape Horn, the net was put astern several times; it never, however, brought up anything besides a few of two extremely minute species of Entomostraca. Yet whales and seals, petrels and albatross, are exceedingly abundant throughout this part of the ocean. It has always been a mystery to me on what the albatross, which lives far from the shore, can subsist; I presume that, like the condor, it is able to fast long; and that one good feast on the carcass of a putrid whale lasts for a long time. The central and intertropical parts of the Atlantic swarm with Pteropoda, Crustacea, and Radiata, and with their devourers the flying-fish, and again with their devourers the bonitos and albicores; I presume that the numerous lower pelagic animals feed on the Infusoria, which are now known, from the researches of Ehrenberg, to abound in the open ocean: but on what, in the clear blue water, do these Infusoria subsist?

While sailing a little south of the Plata on one very dark night, the sea presented a wonderful and most beautiful spectacle. There was a fresh breeze, and every part of the surface, which during the day is seen as foam, now glowed with a pale light. The vessel drove before her bows two billows of liquid phosphorus, and in her wake she was followed by a milky train. As far as the eye reached, the crest of every wave was bright, and the sky above the horizon, from the reflected glare of these livid flames, was not so utterly obscure as over the vault of the heavens.

As we proceed further southward the sea is seldom phosphorescent; and off Cape Horn I do not recollect more than once having seen it so, and then it was far from being brilliant. This circumstance probably has a close connexion with the scarcity of organic beings in that part of the ocean. After the elaborate paper,* by Ehrenberg, on the phosphorescence of the sea, it is almost superfluous on my part to make any observations on the subject. I may however add, that the same torn and irregular particles of gelatinous matter, described by Ehrenberg, seem in the southern as well as in the northern hemisphere, to be the common cause of this phenomenon. The particles were so minute as easily to pass through fine gauze; yet many were distinctly visible by the naked eye. The water when placed in a tumbler and agitated, gave out sparks, but a small portion in a watch-glass scarcely ever was luminous. Ehrenberg states that these particles all retain a certain degree of irritability. My observations, some of which were made directly after taking up the water, gave a different result. I may also mention, that having used the net during one night, I allowed it to become partially dry, and having occasion twelve hours afterwards to employ it again, I found the whole surface sparkled as brightly as when first taken out of the water. It does not appear probable in this case, that the particles could have remained so long alive. On one occasion having kept a jelly-fish of the genus Dianaea till it was dead, the water in which it was placed became luminous. When the waves scintillate with bright green sparks, I believe it is generally owing to minute crustacea. But there can be no doubt that very many other pelagic animals, when alive, are phosphorescent.

* An abstract is given in No. IV. of the Magazine of Zoology and Botany.

On two occasions I have observed the sea luminous at considerable depths beneath the surface. Near the mouth of the Plata some circular and oval patches, from two to four yards in diameter, and with defined outlines, shone with a steady but pale light; while the surrounding water only gave out a few sparks. The appearance resembled the reflection of the moon, or some luminous body; for the edges were sinuous from the undulations of the surface. The ship, which drew thirteen feet of {sic, no “of” here} water, passed over, without disturbing these patches. Therefore we must suppose that some animals were congregated together at a greater depth than the bottom of the vessel.

Near Fernando Noronha the sea gave out light in flashes. The appearance was very similar to that which might be expected from a large fish moving rapidly through a luminous fluid. To this cause the sailors attributed it; at the time, however, I entertained some doubts, on account of the frequency and rapidity of the flashes. I have already remarked that the phenomenon is very much more common in warm than in cold countries; and I have sometimes imagined that a disturbed electrical condition of the atmosphere was most favourable to its production. Certainly I think the sea is most luminous after a few days of more calm weather than ordinary, during which time it has swarmed with various animals. Observing that the water charged with gelatinous particles is in an impure state, and that the luminous appearance in all common cases is produced by the agitation of the fluid in contact with the atmosphere, I am inclined to consider that the phosphorescence is the result of the decomposition of the organic particles, by which process (one is tempted almost to call it a kind of respiration) the ocean becomes purified.

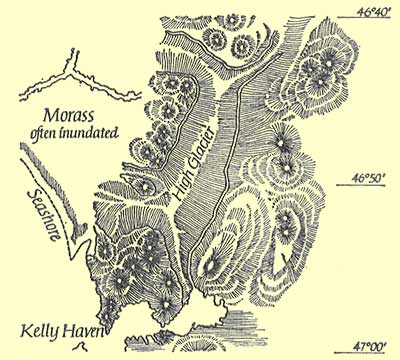

December 23rd.—We arrived at Port Desire,  situated in lat. 47°,§ on the coast of Patagonia. The creek runs for about twenty miles inland, with an irregular width. The Beagle anchored a few miles within the entrance, in front of the ruins of an old Spanish settlement.

situated in lat. 47°,§ on the coast of Patagonia. The creek runs for about twenty miles inland, with an irregular width. The Beagle anchored a few miles within the entrance, in front of the ruins of an old Spanish settlement.

§ Earlier (August, 1833), Darwin gave the latitude as 48°.

The same evening I went on shore. The first landing in any new country is very interesting, and especially when, as in this case, the whole aspect bears the stamp of a marked and individual character. At the height of between two and three hundred feet above some masses of porphyry a wide plain extends, which is truly characteristic of Patagonia. The surface is quite level, and is composed of well-rounded shingle mixed with a whitish earth. Here and there scattered tufts of brown wiry grass are supported, and still more rarely, some low thorny bushes. The weather is dry and pleasant, and the fine blue sky is but seldom obscured. When standing in the middle of one of these desert plains and looking towards the interior, the view is generally bounded by the escarpment of another plain, rather higher, but equally level and desolate; and in every other direction the horizon is indistinct from the trembling mirage which seems to rise from the heated surface.

In such a country the fate of the Spanish settlement was soon decided; the dryness of the climate during the greater part of the year, and the occasional hostile attacks of the wandering Indians, compelled the colonists to desert their half-finished buildings. The style, however, in which they were commenced shows the strong and liberal hand of Spain in the old time. The result of all the attempts to colonize this side of America south of 41°, has been miserable. Port Famine expresses by its name the lingering and extreme sufferings of several hundred wretched people, of whom one alone survived to relate their misfortunes. At St. Joseph's Bay,  § on the coast of Patagonia, a small settlement was made; but during one Sunday the Indians made an attack and massacred the whole party, excepting two men, who remained captives during many years. At the Rio Negro I conversed with one of these men, now in extreme old age.

§ on the coast of Patagonia, a small settlement was made; but during one Sunday the Indians made an attack and massacred the whole party, excepting two men, who remained captives during many years. At the Rio Negro I conversed with one of these men, now in extreme old age.

§ Presumably, FitzRoy's Bay of San José.

The zoology of Patagonia is as limited as its flora.* On the arid plains a few black beetles (Heteromera) might be seen slowly crawling about, and occasionally a lizard darted from side to side. Of birds we have three carrion hawks and in the valleys a few finches and insect-feeders. An ibis (Theristicus melanops—a species said to be found in central Africa) is not uncommon on the most desert parts: in their stomachs I found grasshoppers, cicadae, small lizards, and even scorpions.† At one time of the year these birds go in flocks, at another in pairs, their cry is very loud and singular, like the neighing of the guanaco.

* I found here a species of cactus, described by Professor Henslow, under the name of Opuntia Darwinii (Magazine of Zoology and Botany, vol. i. p. 466), which was remarkable for the irritability of the stamens, when I inserted either a piece of stick or the end of my finger in the flower. The segments of the perianth also closed on the pistil, but more slowly than the stamens. Plants of this family, generally considered as tropical, occur in North America (Lewis and Clarke's Travels, p. 221), in the same high latitude as here, namely, in both cases, in 47°.

† These insects were not uncommon beneath stones. I found one cannibal scorpion quietly devouring another.

The guanaco, or wild llama, is the characteristic quadruped of the plains of Patagonia; it is the South American representative of the camel of the East. It is an elegant animal in a state of nature, with a long slender neck and fine legs. It is very common over the whole of the temperate parts of the continent, as far south as the islands near Cape Horn. It generally lives in small herds of from half a dozen to thirty in each; but on the banks of the St. Cruz we saw one herd which must have contained at least five hundred.

They are generally wild and extremely wary. Mr. Stokes told me, that he one day saw through a glass a herd of these animals which evidently had been frightened, and were running away at full speed, although their distance was so great that he could not distinguish them with his naked eye. The sportsman frequently receives the first notice of their presence, by hearing from a long distance their peculiar shrill neighing note of alarm. If he then looks attentively, he will probably see the herd standing in a line on the side of some distant hill. On approaching nearer, a few more squeals are given, and off they set at an apparently slow, but really quick canter, along some narrow beaten track to a neighbouring hill. If, however, by chance he abruptly meets a single animal, or several together, they will generally stand motionless and intently gaze at him; then perhaps move on a few yards, turn round, and look again. What is the cause of this difference in their shyness? Do they mistake a man in the distance for their chief enemy the puma? Or does curiosity overcome their timidity? That they are curious is certain; for if a person lies on the ground, and plays strange antics, such as throwing up his feet in the air, they will almost always approach by degrees to reconnoitre him. It was an artifice that was repeatedly practised by our sportsmen with success, and it had moreover the advantage of allowing several shots to be fired, which were all taken as parts of the performance. On the mountains of Tierra del Fuego, I have more than once seen a guanaco, on being approached, not only neigh and squeal, but prance and leap about in the most ridiculous manner, apparently in defiance as a challenge. These animals are very easily domesticated, and I have seen some thus kept in northern Patagonia near a house, though not under any restraint. They are in this state very bold, and readily attack a man by striking him from behind with both knees. It is asserted that the motive for these attacks is jealousy on account of their females. The wild guanacos, however, have no idea of defence; even a single dog will secure one of these large animals, till the huntsman can come up. In many of their habits they are like sheep in a flock. Thus when they see men approaching in several directions on horseback, they soon become bewildered, and know not which way to run. This greatly facilitates the Indian method of hunting, for they are thus easily driven to a central point, and are encompassed.

The guanacos readily take to the water: several times at Port Valdes  they were seen swimming from island to island. Byron, in his voyage says he saw them drinking salt water. Some of our officers likewise saw a herd apparently drinking the briny fluid from a salina near Cape Blanco. I imagine in several parts of the country, if they do not drink salt water, they drink none at all. In the middle of the day they frequently roll in the dust, in saucer-shaped hollows. The males fight together; two one day passed quite close to me, squealing and trying to bite each other; and several were shot with their hides deeply scored. Herds sometimes appear to set out on exploring parties: at Bahia Blanca, where, within thirty miles of the coast, these animals are extremely unfrequent, I one day saw the tracks of thirty or forty, which had come in a direct line to a muddy salt-water creek. They then must have perceived that they were approaching the sea, for they had wheeled with the regularity of cavalry, and had returned back in as straight a line as they had advanced. The guanacos have one singular habit, which is to me quite inexplicable; namely, that on successive days they drop their dung in the same defined heap. I saw one of these heaps which was eight feet in diameter, and was composed of a large quantity. This habit, according to M. A. d'Orbigny, is common to all the species of the genus; it is very useful to the Peruvian Indians, who use the dung for fuel, and are thus saved the trouble of collecting it.

they were seen swimming from island to island. Byron, in his voyage says he saw them drinking salt water. Some of our officers likewise saw a herd apparently drinking the briny fluid from a salina near Cape Blanco. I imagine in several parts of the country, if they do not drink salt water, they drink none at all. In the middle of the day they frequently roll in the dust, in saucer-shaped hollows. The males fight together; two one day passed quite close to me, squealing and trying to bite each other; and several were shot with their hides deeply scored. Herds sometimes appear to set out on exploring parties: at Bahia Blanca, where, within thirty miles of the coast, these animals are extremely unfrequent, I one day saw the tracks of thirty or forty, which had come in a direct line to a muddy salt-water creek. They then must have perceived that they were approaching the sea, for they had wheeled with the regularity of cavalry, and had returned back in as straight a line as they had advanced. The guanacos have one singular habit, which is to me quite inexplicable; namely, that on successive days they drop their dung in the same defined heap. I saw one of these heaps which was eight feet in diameter, and was composed of a large quantity. This habit, according to M. A. d'Orbigny, is common to all the species of the genus; it is very useful to the Peruvian Indians, who use the dung for fuel, and are thus saved the trouble of collecting it.