Skyring's chart—Noir Island—Penguins—Fuegians—Sarmiento—Townshend Harbour—Horace Peaks—Cape Desolation—Boat lost—Basket—Search in Desolate Bay—Natives—Heavy gale—Surprise—Seizure—Consequences—Return to Beagle—Sail to Stewart Harbour—Set out again—Escape of Natives—Unavailing search—Discomforts—Tides—Nature of Coast—Doris Cove—Christmas Sound—Cook—York-Minster—March Harbour—Build a boat—Treacherous rocks—Skirmish with the Natives—Captives—Boat Memory—Petrel.

“25th. We weighed, and went round to Fury Harbour, for the carpenter and his cargo, and met him with a spar and a raft of plank, taken from the wreck. Having hoisted the boat up, and got the plank on board, we stood out towards the West Furies, by the wind; my intention being either to sail round Noir Island, or anchor under it, before running to the eastward, in order that no part of the sea-coast might be left unexamined. We passed very near some of the rocks, but as the day was fine and the weather clear, a good look-out at the mast-head could be trusted.

“Before leaving the vicinity of Mount Skyring, I should remark that the true bearing of Mount Sarmiento's summit, which I obtained from the top of Mount Skyring, laid off on Lieutenant Skyring's chart, passed as truly through his position of the summit as if the line had been merely drawn between them. This is highly creditable to his work, for I know he did not himself see Mount Sarmiento, when upon Mount Skyring.

“The breeze freshened, and drew more to the westward towards evening, I had therefore no hopes of nearing Noir Island. We saw the Tower Rocks distinctly before dark, and stood on towards them until ten o'clock, closing Scylla to avoid Charybdis, for in-shore of us lay all those scattered rocks, among which we had steered when passing the Agnes Islands and Cape Kempe.

“The night was spent in making short boards, under reefed topsails, over the same two miles of ground, as nearly as possible, with the lead going, and a thoroughly good look-out. At daylight next morning the wind became strong and the weather thick, with rain, but we made as much sail as we could carry, and worked to windward all the day. In the afternoon it moderated, and before dark we anchored in a very good roadstead, at the east end of Noir Island, sheltered from all winds from N. to S. b. E. (by the west); over a clear, sandy bottom; and with a sheltered cove near us where boats may land easily, and get plenty of wood and water. In working up to the Island, we passed very near a dangerous rock, under water, lying four miles off shore; and another, near the anchorage. The sea does not break on either of them when there is not much swell.

“27th. A fine day favoured us; the master went to one part of the island, and Mr. Stokes to another, while I went to a third. Having taken angles at the extreme west point (which ends in a cluster of rocks like needles), I passed quite round the island, and returned to the anchorage after dusk, landing here and there for bearings, in my way.

“There is a cove at the south part of the island, where boats would be perfectly safe in any weather, but the entrance is too narrow for decked vessels. The island itself is narrow and long, apparently the top of a ridge of mountains, and formed of sandstone,* which accounts for the bottom near it being so good, and for the needle-like appearance of the rocks at the west end; as the sand-stone, being very soft, is continually wearing away by the action of the water.

“Multitudes of penguins were swarming together in some parts of the island, among the bushes and ‘tussac’* near the shore, having gone there for the purposes of moulting and rearing their young. They were very valiant in self-defence, and ran open-mouthed, by dozens, at any one who invaded their territory, little knowing how soon a stick could scatter them on the ground. The young were good eating, but the others proved to be black and tough, when cooked. The manner in which they feed their young is curious, and rather amusing. The old bird gets on a little eminence, and makes a great noise (between quacking and braying), holding its head up in the air, as if it were haranguing the penguinnery, while the young one stands close to it, but a little lower. The old bird having continued its clatter for about a minute, puts its head down, and opens its mouth widely, into which the young one thrusts its head, and then appears to suck from the throat of its mother for a minute or two, after which the clatter is repeated, and the young one is again fed; this continues for about ten minutes. I observed some which were moulting make the same noise, and then apparently swallow what they thus supplied themselves with; so in this way I suppose they are furnished with subsistence during the time they cannot seek it in the water. Many hair seal were seen about the island, and three were killed. Wild fowl were very numerous. Strange to say, traces of the Fuegians (a wigwam, &c.) were found, which shows how far they will at times venture in their canoes.

“No danger lies outside of Noir Island, except in the Tower Rocks, which are above water, and ‘steep-to,’ but many perils lie to the south-eastward. Indeed, a worse place than the neighbourhood of Cape Kempe and the Agnes Islands could not often be found, I think: the chart of it, with all its stars to mark the rocks, looks like a map of part of the heavens, rather than part of the earth.

“28th. At daylight we sailed from these roads, and passed close to the Tower Rocks (within half a cable's length): they are two only in number, a mile and a half apart, and steep-sided. Thence we steered towards St. Paul's, my intention being to seek an anchorage in that direction. This day proved very fine and so clear that when we were becalmed, off St. Paul's, we saw Mount Sarmiento distinctly from the deck. A breeze carried us through Pratt Passage, which separates London Island from Sydney Island, to an anchorage in a good harbour, under a high peaked hill (Horace Peaks), which is a good mark for it. Finding no soundings in the Passage as we approached, gave us reason to be anxious; but in the harbour, the bottom proved to be excellent, and the water only of a moderate depth. As soon as we anchored, I tried to ascend Horace Peaks, but returned without having reached their summits before dark; however, I saw enough to give me a general idea of the distribution of the land and water near us. I thought that this anchorage would be favourable for ascertaining the latitude of Cape Schomberg* with exactness: having found a considerable difference between our chart and that of Lieutenant Skyring, respecting the latitude of that promontory.

“Meanwhile I contemplated sending the master to a headland called by Cook, Cape Desolation, and which well deserves the name, being a high, craggy, barren range of land. I was not sorry to find myself in a safe anchorage, for the weather seemed lowering; and after being favoured with some moderate days, we could not but expect a share of wind and rain.

“29th. This morning the weather looked as if we should be repaid for the few fine days which we had enjoyed; but as we felt it necessary to work in bad weather as well as in good, it did not prevent the master from setting out on his way to Cape Desolation; near which, as a conspicuous headland, whose position would be of great consequence, he was to search for a harbour, and obtain observations for connecting the survey. He could not have been in a finer boat (a whale-boat built by Mr. May, at San Carlos); and as he well knew what to do with her, I did not feel uneasy for his safety, although after his departure the wind increased rapidly, and towards evening blew a hard gale. The barometer had not given so much warning as usual; but it had been falling gradually since our arrival in this harbour, and continued to fall. The sympiesometer had been more on the alert, and had fallen more rapidly.

“(30th.) A continued gale, with rain and thick weather throughout the clay. During the night the weather became rather more moderate; but on the morning of the 31st, the wind again increased to a gale, and towards noon, the williwaws were so violent, that our small cutter, lying astern of the ship, was fairly capsized, though she had not even a mast standing. The ship herself careened, as if under a press of sail, sending all loose things to leeward with a general crash (not being secured for sea, while moored in so small a cove), but so rapidly did these blasts from the mountains pass by, that with a good scope of chain out, it was hardly strained to its utmost before the squall was over. While the gale was increasing, in the afternoon, the topmasts were struck; yet still, in the squalls, the vessel heeled many strakes when they caught her a-beam. At night they followed in such rapid succession, that if the holding-ground had not been excellent, and our ground-tackle very strong, we must have been driven on the rocks.

“Under the lee of high land is not the best anchorage in these regions. When good holding-ground can be found to windward of a height, and low land lies to windward of the anchorage, sufficient to break the sea, the place is much to be preferred; because the wind is steady and does not blow home against the height. The lee side of these heights is a great deal worse than the west side of Gibraltar Rock while the strongest Levanter is blowing.

“Considering that this month corresponds to August in our climate, it is natural to compare them, and to think how hay and corn would prosper in a Fuegian summer. As yet I have found no difference in Tierra del Fuego between summer and winter, excepting that in the former the days are longer, and the average temperature is perhaps ten degrees higher, but there is also then more wind and rain.

“The gale still continued, and prevented any thing being done out of the ship. However safe a cove Mr. Murray might have found, his time, I knew, must be passing most irksomely, as he could not have moved about since the day he left us. He had a week's provisions, but with moderate weather would have returned in three days.

“Feb. 2d. Still very squally and unsettled. This gale began at N.N.W., and drew round to S.S.W. Much rain comes usually from the N.W. quarter; and as the wind draws southward, the weather becomes clearer. The squalls from the southern quarter bring a great deal of hail with them.

“3d. I was enabled to take a round of angles from Horace Peaks, over the ship, the sky being clear near the horizon. The theodolite had been left near the top since the 28th, each day having been too bad to use it. These peaked hills required time and exertion in the ascent; but the wide range of view obtained from their summits on a clear day, amply repaid us for both. If the height was sufficient, it gave a bird's-eye view of many leagues, and showed at a glance where channels lay, which were islands, and what was the nature of the surrounding land and water. The shattered state of all these peaks is remarkable: frost, I think, must be the chief cause.

“After being deceived by the magnetism of Mount Skyring and other places, I never trusted the compass on a height, but always set up a mark near the water, at some distance, and from it obtained the astronomical bearing of my station at the summit. This afternoon we prepared the ship to proceed as soon as the master should arrive.

“4th. Moderate weather. I was surprised that the master did not make his appearance; yet, having full confidence in his prudent management, and knowing that he had been all the time among islands, upon any one of which he could haul up his boat and remain in safety during the gales, I did not feel much anxiety, but supposed he was staying to take the necessary angles and observations, in which he had been delayed by the very bad weather we had lately experienced.

“At three this morning (5th), I was called up to hear that the whale-boat was lost—stolen by the natives; and that her coxswain and two men had just reached the ship in a clumsy canoe, made like a large basket, of wicker-work covered with pieces of canvas, and lined with clay, very leaky, and difficult to paddle. They had been sent by the master, who, with the other people, was at the cove under Cape Desolation, where they stopped on the first day. Their provisions were all consumed, two-thirds having been stolen with the boat, and the return of the natives, to plunder, and perhaps kill them, was expected daily.

“The basket, I cannot call it a canoe, left the Cape (now doubly deserving of its name) early on the morning of the 4th, and worked its way slowly and heavily amongst the islands, the men having only one biscuit each with them. They paddled all day, and the following night, until two o'clock this morning (5th), when in passing the cove where the ship lay, they heard one of our dogs bark, and found their way to us quite worn out by fatigue and hunger. Not a moment was lost, my boat was immediately prepared, and I hastened away with a fortnight's provisions for eleven men, intending to relieve the master, and then go in search of the stolen boat. The weather was rainy, and the wind fresh and squally; but at eleven o'clock I reached the cove, having passed to seaward of the cape, and there found Mr. Murray anxiously, but doubtfully, awaiting my arrival. My first object, after inquiring into the business, was to scrutinize minutely the place where the boat had been moored, (for I could not believe that she had been stolen;) but I was soon convinced that she had been well secured in a perfectly safe place, and that she must, indeed, have been taken away, just before daylight, by the natives. Her mast and sails, and part of the provisions were in her; but the men's clothes and the instruments had fortunately been landed. It was the usual custom with our boats, when away from the ship, to keep a watch at night; but this place appeared so isolated and desolate, that such a precaution did not seem necessary. Had I been with the boat, I should probably have lost her in the same manner; for I only kept a watch when I thought there was occasion, as I would not harass the boat's crew unnecessarily; and on this exposed and sea-beaten island, I should not have suspected that Indians would be found. It appeared that a party of them were living in two wigwams, in a little cove about a mile from that in which our boat lay, and must have seen her arrive; while their wigwams were so hidden as to escape the observation of the whale-boat's crew. At two o'clock on the first morning, Mr. Murray sent one of the men out of the tent to see if the boat rode well at her moorings in the cove, and he found her secure. At four another man went to look out, but she was then gone. The crew, doubtful what had been her fate, immediately spread about the shore of the island to seek for traces of her, and in their search they found the wigwams, evidently just deserted: the fire not being extinguished. This at once explained the mystery, and some proceeding along the shore, others went up on the hills to look for her in the offing; but all in vain. The next morning Mr. Murray began the basket, which was made chiefly by two of his men out of small boughs, and some parts of the tent, with a lining of clayey earth at the bottom. Being on an island, about fifteen miles from the Beagle, their plan was as necessary as it was ingenious: though certainly something more like a canoe than a coracle could have been paddled faster.

“The chronometer, theodolite, and other instruments having been saved, Mr. Murray had made observations for fixing the position of the place, and had done all that was required before I arrived, when they embarked, with their things, in my boat, which then contained altogether eleven men, a fortnight's provisions, two tents,* and clothing; yet with this load she travelled many a long mile, during the following week, a proof of the qualities of this five-oared whale-boat, which was also built by Mr. Jonathan May, our carpenter, while we were at San Carlos.

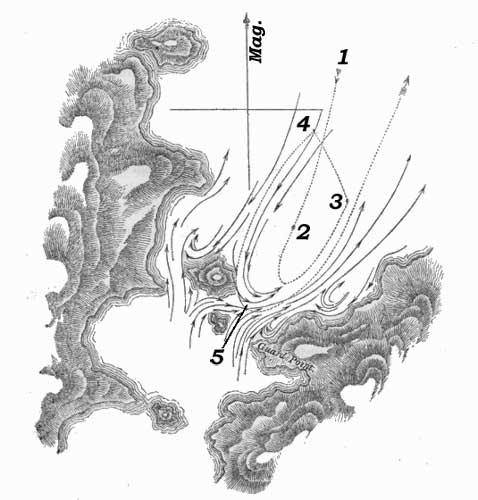

“The very first place we went to, a small island about two miles distant, convinced us still more decidedly of the fate of our lost boat, and gave us hopes of retrieving her; for near a lately used wigwam, we found her mast, part of which had been cut off with an axe that was in the boat. Our next point was then to be considered, for to chase the thieves I was determined. North and east of us, as far as the eye could reach, lay an extensive bay in which were many islands, large and small; and westward was a more connected mass of large islands reaching, apparently, to the foot of that grand chain of snowy mountains, which runs eastward from the Barbara Channel, and over the midst of which Sarmiento proudly towers. I resolved to trace the confines of the bay, from the west, towards the north and east, thinking it probable that the thieves would hasten to some secure cove, at a distance, rather than remain upon an outlying island, whence their retreat might be cut off. In the evening we met a canoe containing two Fuegians, a man and a woman, who made us understand, by signs, that several canoes were gone to the northward. This raised our hopes, and we pushed on. The woman, just mentioned, was the best looking I have seen among the Fuegians, and really well-featured: her voice was pleasing, and her manner neither so suspicious nor timid as that of the rest. Though young she was uncommonly fat, and did justice to a diet of limpets and muscles. Both she and her husband were perfectly naked. Having searched the coves for some distance farther, night came on, and we landed in a sheltered spot.

“The next day (6th), we found some rather doubtful traces of the thieves. Towards night it blew a strong gale, with hailsqualls and rain.

“On the 7th, at a place more than thirty miles E.N.E. of Cape Desolation, we fell in with a native family, and on searching their two canoes found our boat's lead line. This was a prize indeed; and we immediately took the man who had it into our boat, making him comprehend that he must show us where the people were, from whom he got it. He understood our meaning well enough, and following his guidance we reached a cove that afternoon, in which were two canoes full of women and children; but only one old man, and a lad of seventeen or eighteen. As usual with the Fuegians, upon perceiving us they all ran away into the bushes, carrying off as much of their property as possible—returning again naked, and huddling together in a corner. After a minute search, some of the boat's gear was found, part of her sail, and an oar, the loom of which had been made into a seal-club, and the blade into a paddle. The axe, and the boat's tool-bag were also found, which convinced us that this was the resort of those who had stolen our boat; and that the women, six in number, were their wives. The men were probably absent, in our boat, on a sealing expedition; as a fine large canoe, made of tirplank, perhaps from the wreck of the Saxe Cobourg, was lying on the beach without paddles or spears. She did not come there without paddles: and where were the spears of which every Fuegian family has plenty? It was evident that the men of the party had taken them in our boat, and had cut up our oars like the one they had accidentally left. The women understood what we wanted, and made eager signs to explain to us where our boat was gone. I did not like to injure them, and only took away our own gear, and the young man, who came very readily, to show us where our boat was, and, with the man who had brought us to the place, squatted down in the boat apparently much pleased with some clothes and red caps, which were given to them. We had always behaved kindly to the Fuegians wherever we met them, and did not yet know how to treat them as they deserved, although they had robbed us of so great a treasure, upon the recovery or loss of which much of the success of our voyage depended. Following the guidance of these two natives, we pulled against wind and rain until dark, when it became absolutely necessary to secure our boat for the night, deeply laden as she was with thirteen people. As we were then at a great distance from the place, whence we brought the natives, having pulled for four hours along shore, and as they seemed to be quite at their ease, and contented, I would not secure our guides as prisoners, but allowed them to lie by the fire in charge of the man on watch. About an hour before daylight, although the look-out man was only a few yards distant from the fire, they slipped into the bushes, and as it was almost dark were immediately out of sight. Their escape was discovered directly, but to search for them during darkness, in a thick wood, would have been useless; besides, our men were tired with their day's work, and wanted rest, so I would not disturb them until daylight (8th), when we continued our search in the direction the natives had indicated; but after examining several coves without finding any traces of Fuegians, we hastened back towards the wigwams we had visited on the previous day. Sailing close along-shore, a large smoke suddenly rose up, out of a small cove close by us, where we immediately landed, and looked all round; but found only the foot-prints of two Fuegians, probably the runaways, who had just succeeded in lighting a fire at the moment we passed by. This shows how quickly they find materials for the purpose, for when they left us, they had neither iron nor fire-stone (pyrites), nor any kind of tinder. They had carried off two tarpaulin coats, which Mr. Murray had kindly put on to keep them warm; although, treated as he had so lately been, one might have thought he would not have been the first to care for their comfort. I mention these incidents to show what was our behaviour to these savages, and that no wanton cruelty was exercised towards them.

“After looking for these two natives, and for Mr. Murray's coats, which at that time he could ill spare, we returned to our boat, and pushed on towards the wigwams. The moment the inmates saw us, they ran away, and we gave chase, trying, in vain, to make them stop. Disappointed in the hope of obtaining a guide, we determined to prevent these people from escaping far, and spreading any intelligence likely to impede the return of our boat, which we daily expected: we therefore destroyed two canoes, and part of a third, that the natives were building, and burned every material which could be useful to them in making another canoe.

“(9th). Next day, we went straight across the bay to Cape Desolation, against a fresh breeze: by pulling in turns, the boat was kept going fast through the water, and late in the evening we reached the cove from which the thieves had first started, when they stole the boat; but no traces of their having been there again, were found. I thought it probable that they would return to see what had become of our party, and whether our people were weak enough to be plundered again, or perhaps attacked.

“This idea proving wrong, we retraced (10th) much of our former course, because the direction pointed out by the Fuegians who ran away from us seemed to lead towards the place we now steered for, Courtenay Sound, and was a probable line for the thieves to take. During the night it blew a gale from the southward, which increased next day (11th), and became more and more violent until the morning of the 12th, when it abated.

“We continued our search, however, sometimes under a close-reefed sail; sometimes on our oars, and sometimes scudding with only the mast up. Although the wind was very violent, too strong for a close reefed sail (with four reefs), the water was too much confined by islands to rise into a sea, but it was blown, as ‘spoon drift,’ in all directions. This day the Beagle had her topmasts and lower yards struck, for the gale was extremely heavy where she lay. The barometer foretold it very well, falling more than I had previously seen, although the wind was southerly. In an exposed anchorage, I do not think any vessel could have rode it out, however good the holding ground.

“12th. This morning the weather was better, and improving fast. We went over much ground without the smallest success, and in the afternoon steered to the eastward again, for a third visit to the boat stealers' family. As it was late when we approached the place, I landed half our party, and with the rest went to reconnoitre. After a long search we discovered the Indians in a cove, at some distance from that in which they were on the previous day; and having ascertained this point, taken a good view of the ground, and formed our plans, we returned to our companions, and prepared for surprising the natives and making them prisoners. My wish was to surround them unawares, and take as many as possible, to be kept as hostages for the return of our boat, or else to make them show us where she was; and, meanwhile, it was an object to prevent any from escaping to give the alarm.

“13th. Whether the men belonging to the tribe had returned during our absence, was uncertain, as we could not, without risk of discovery, get near enough to ascertain: but, in case we should find them, we went armed, each with a pistol or gun, a cutlass, and a piece of rope to secure a prisoner. We landed at some distance from the cove, and, leaving two men with our boat, crept quietly through the bushes for a long distance round, until we were quite at the back of the new wigwams; then closing gradually in a circle, we reached almost to the spot undiscovered; but their dogs winded us, and all at once ran towards us barking loudly. Further concealment was impossible, so we rushed on as fast as we could through the bushes. At first the Indians began to run away; but hearing us shout on both sides, some tried to hide themselves, by squatting under the banks of a stream of water. The foremost of our party, Elsmore by name, in jumping across this stream, slipped, and fell in just where two men and a woman were concealed: they instantly attacked him, trying to hold him down and beat out his brains with stones; and before any one could assist him, he had received several severe blows, and one eye was almost destroyed, by a dangerous stroke near the temple. Mr. Murray, seeing the man's danger, fired at one of the Fuegians, who staggered back and let Elsmore escape; but immediately recovering himself, picked up stones from the bed of the stream, or was supplied with them by those who stood close to him, and threw them from each hand with astonishing force and precision. His first stone struck the master with much force, broke a powder-horn hung round his neck, and nearly knocked him backwards: and two others were thrown so truly at the heads of those nearest him, that they barely saved themselves by dropping down. All this passed in a few seconds, so quick was he with each hand: but, poor fellow, it was his last struggle; unfortunately he was mortally wounded, and, throwing one more stone, he fell against the bank and expired. After some struggling, and a few hard blows, those who tried to secrete themselves were taken, but several who ran away along the beach escaped: so strong and stout were the females, that I, for one, had no idea that it was a woman, whose arms I and my coxswain endeavoured to pinion, until I heard someone say so. The oldest woman of the tribe was so powerful, that two of the strongest men of our party could scarcely pull her out from under the bank of the stream. The man who was shot was one of those whom we had taken in the boat as a guide, and the other was among our prisoners. Mr. Murray's coats were found in the wigwams divided into wrappers to throw over the shoulders. We embarked the Indians (two men, three women, and six children), and returned to the spot where we had passed the preceding night. One man who escaped was a one-eyed man we had seen before; he was more active than any, and soon out of our reach. Two or three others escaped with him, whom I did not see distinctly.

“That a life should have been lost in the struggle, I lament deeply; but if the Fuegian had not been shot at that moment, his next blow might have killed Elsmore, who was almost under water, and more than half stunned, for he had scarcely sense to struggle away, upon feeling the man's grasp relax. When fairly embarked, and before we asked any questions, the natives seemed very anxious to tell us where our boat was; but pointed in a direction quite opposite to that which they had previously shown us. We guarded them carefully through the night, and next morning (14th) set out upon our return to the Beagle, with twenty-two souls in the boat. My object was, to put them in security on board, run down the coast with the ship to some harbour more to the eastward, and then set out again upon another search; carrying some of my prisoners as guides, and leaving the rest on board to ensure the former remaining, and not deceiving us. We made tolerable progress, though the boat was so over-loaded, and on the 15th reached the Beagle with our living cargo. In our way we fell in with a family of natives, whose wigwams and canoes we searched; but finding none of our property, we left them not only unmolested, but gave them a few things, which in their eyes were valuable.

“This conduct appeared to surprise our prisoners, who, as far as we could make out, received a wholesome lecture, of assistance, from the strangers. At all events, when they parted, our passengers were as discontented as the others were cheerful. When we got on board, we fed our prisoners with fat pork and shell-fish, which they liked better than any thing else, and clothed them with old blankets.*

“Next morning (16th) we weighed, and sailed along the coast towards Cape Castlereagh, at the east side of Desolate Bay. Many straggling rocks and rocky islets were observed lying off Cape Desolation and in the Bay. That afternoon, we stood into a narrow opening, which appeared to be the outlet of a harbour close to Cape Castlereagh, and found a very good anchorage, well suited for the purposes both of continuing the survey and looking for the lost boat.

“(17th.) The master and I, with the cutter and a whaleboat, set out upon a second chase, taking a week's provisions. In the first cove I searched, not two miles from the Beagle, I found a piece of the boat's lead-line, which had been left in a lately deserted wigwam. This raised our hopes; and, in addition to the signs made by our prisoners, convinced us we were on the right track.

“I took with me a young man as a guide, and in the cutter the master carried the two stoutest of the women, having left all the rest of our prisoners on board. As far as we could make out, they appeared to understand perfectly that their safety and future freedom depended upon their showing us where to find the boat.

“We intended to go round the Stewart Islands; and after examining many coves, and finding signs that a party of natives had passed along the same route within the last two days, we stopped in a sheltered place for the night. Having given our prisoners as much food as they could eat, muscles, limpets, and pork, we let them lie down close to the fire, all three together. I would not tie them, neither did I think it necessary to keep an unusual watch, supposing that their children being left in our vessel was a security for the mothers far stronger than rope or iron. I kept watch myself during the first part of the night, as the men were tired by pulling all day, and incautiously allowed the Fuegians to lie between the fire and the bushes, having covered them up so snugly, with old blankets and my own poncho, that their bodies were entirely hidden. About midnight, while standing on the opposite side of the fire, looking at the boats, with my back to the Fuegians, I heard a rustling noise, and turned round; but seeing the heap of blankets unmoved, satisfied me, and I stooped down to the fire to look at my watch. At this moment, another rustle, and my dog jumping up and barking, told me that the natives had escaped. Still the blankets looked the same, for they were artfully propped up by bushes. All our party began immediately to search for them; but as the night was quite dark, and there was a thick wood close to us, our exertions were unavailing.

“Believing that we could not be far from the place where the natives supposed our boat to be, I thought that they would go directly and warn their people of our approach; and as the island was narrow, though long, a very little travelling would take them across to the part they had pointed out to us, while it might take a boat a considerable time to go round; I therefore started immediately to continue the search in that direction, and left the master to examine every place near our tents.

“In the afternoon of the same day I returned to him, having traversed a long extent of coast without finding an outlet to sea-ward, or any traces of the lost boat. Meanwhile Mr. Murray had searched every place near our bivouac without success; but he found the spot where the Fuegians had concealed themselves during the night, under the roots of a large tree, only a dozen yards from our fire.

“As it was possible that the thieves might have returned to the place whence we had taken the natives, I desired the master to cross the sound and go there, and afterwards return to meet me, while I continued the search eastward. With a fair and fresh wind I made a good run that evening, found a passage opening to the sea,* and a wigwam just deserted. Here was cause for hope; and seeing, beyond the passage, some large islands lying to seaward of that which we had been coasting, it appeared probable that our boat had been taken there for seal-fishing. Our prisoners had given us to understand plainly enough that such was the object of those who had stolen her, and outlying islands were the most likely to be visited, as on them most seal are found.

“Next day (19th) I passed over to Gilbert Island, and in a cove found such recent marks of natives, that I felt sure of coming up with the chase in the course of the day. When the Fuegians stop anywhere, they generally bark a few trees, to repair their canoes or cover their wigwams; but those whose traces we were following, had made long journeys without stopping; and, where they did stay, barked no trees, which was one reason for supposing them to be the party in our boat. In the course of the day we pulled nearly round the islands,* looking into every cove.

“On the 20th, we discovered three small canoes with their owners in a cove.* All the men ran away, except two. As we saw that there were no more persons than the canoes required, we did not try to catch them, knowing that this could not be the party we were in search of. We had now examined every nook and corner about these islands, and I began to give up all hope of finding our boat in this direction. Having no clue to guide me farther, and much time having been lost, I reluctantly decided to return to the Beagle. Our only remaining hope, that the master might have met with the boat, was but very feeble.

“(21st.) All this day we were pulling to the westward, to regain the Beagle. At night-fall I met Mr. Murray, with the cutter, in the cove where I had appointed a rendezvous. He had not found any signs of the boat upon the opposite shore, and therefore returned; but he saw the people who had escaped from us when we surprised the whole family. They fled as soon as his boat was seen. Leaving, therefore, three men to watch in the bushes, he stood out to sea in the boat; and the stratagem succeeded sufficiently to enable our men to get very near to the natives, but not to catch any of them. One old man squinted very much, and in other respects exactly answered the description of a Fuegian who ill-treated some of the Saxe Cobourg's crew, when they were cast away in Fury Harbour. I wish we could have secured him; but he was always on the alert, and too nimble for our people. In their canoe, which was taken, was found the sleeve of Mr. Murray's tarpaulin coat, a proof that these people belonged to the tribe which had stolen our boat. The canoe was a wretchedly patched affair, evidently put together in a great hurry.

“Next morning (22d) the master and I set out on our return to the Beagle; but seeing a great smoke on the opposite shore, in Thieves' Sound, I thought it must be made by the offenders, who, having returned and found their home desolate, were making signals to discover where their family was gone: sending the cutter therefore on board, I pulled across the sound towards the smoke. As the distance was long, and the wind fresh against us, it was late before I arrived; yet the smoke rose as thickly as ever, exciting our expectations to the utmost:—but, to our disappointment, not a living creature could be seen near the fire, nor could any traces of natives be found. The fire must have been kindled in the morning, and as the weather was dry, had continued to burn all day.

“We were then just as much at a loss as ever, for probably (if that was the party), they had seen us, and would, for the future, be doubly watchful. At first we had a chance of coming upon them unawares, but the time for that had passed: every canoe in the sound had been examined, and all its inhabitants knew well what we were seeking.

“It blew too strong, and it was too late, to recross Whaleboat Sound that night, so I ascended a height to look round. Next morning (23d) we again searched many miles of the shores of Thieves' Sound without anv success; and afterwards sailed across to Stewart Harbour. We reached the Beagle in the evening, but found that all the other prisoners, excepting three children, had escaped by swimming ashore during the preceding night. Thus, after much trouble and anxiety, much valuable time lost, and as fine a boat of her kind as ever was seen being stolen from us by these savages, I found myself with three young children to take care of, and no prospect whatever of recovering the boat. It was very hard work for the boats' crews, for during the first ten days we had incessant rainy weather, with gales of wind; and though the last few days had been uncommonly fine, the men's exertions in pulling about among the coves, and in ascending hills, had been extremely fatiguing.

“While the bad weather lasted, the men's clothes were seldom dry, either by day or night. Frequently they were soaked by rain during the greater part of the day, and at night they were in no better condition; for although a large fire (when made) might dry one side, the other as quickly became wet. Obliged, as we were, to pitch our small tent close to the water in order to be near our boat;—and because every other place was either rocky or covered with wood;—we were more than once awakened out of a sound sleep by finding that we were lying partly in the water, the night-tide having risen very much above that of the preceding day: although the tides should have been at that time ‘taking off’ (diminishing).

“Sometimes extreme difficulty was found in lighting a fire, because every thing was saturated with moisture; and hours have been passed in vain attempts, while every one was shivering with cold,—having no shelter from the pouring rain,—and after having been cramped in a small boat during the whole day.

“In Courtenay Sound I saw many nests of shags (cormorants) among the branches of trees near the water: until then, I had understood that those birds usually, if not invariably, built their nests on the ground or in cliffs.

“Much time had certainly been spent in this search, yet it ought not to be considered as altogether lost. Mr. Stokes had been hard at work during my absence, making plans of the harbours, and taking observations, and I am happy to say, that I had reason to place great confidence in his work, for he had always taken the utmost pains, and had been most careful. My wanderings had shown me that from the apparent sea coast to the base of that snowy chain of mountains which runs eastward from the Barbara Channel, there is much more water than land, and that a number of islands, lying near together, form the apparently connected coast; within which a wide sound-like passage extends, opening in places into bays and gulfs, where islands, islets, rocks and breakers, are very numerous. These waters wash the foot of the snowy chain which forms a continued barrier from the Barbara Channel to the Strait of Le Maire. This cruise had also given me more insight into the real character of the Fuegians, than I had then acquired by other means, and gave us all a severe warning which might prove very useful at a future day, when among more numerous tribes who would not be contented with a boat alone. Considering the extent of coast we had already examined, we ought to be thankful for having experienced no other disaster of any kind, and for having had the means of replacing this loss.

“I became convinced that so long as we were ignorant of the Fuegian language, and the natives were equally ignorant of ours, we should never know much about them, or the interior of their country; nor would there be the slightest chance of their being raised one step above the low place which they then held in our estimation. Their words seemed to be short, but to have many meanings, and their pronunciation was harsh and guttural.

“Stewart Harbour, in which the Beagle remained during the last boat cruise, proved to be a good one, and, having three outlets, may be entered or quitted with any wind, and without warping. Wood and water are as abundant as in other Fuegian harbours; and it may be easily known by the remarkable appearance of Cape Castlereagh, which is on the island that shelters the anchorage from the S.W. wind and sea. The outlets are narrow, and can only be passed with a leading wind; but if one does not serve, another will answer. It should be noticed, that there are two rocks nearly in the middle of the harbour, which are just awash at high water. A heavy swell is generally found outside, owing to the comparatively shallow water, in which there are soundings to about three miles from the Cape. In the entrances are from ten to twenty fathoms, therefore if the wind should baffle, or fail, an anchor may be dropped at any moment.

“In my last search among the Gilbert Islands, I found a good harbour for shipping, conveniently situated for carrying on the survey, in a place which otherwise I should certainly have overlooked: and to that harbour I decided on proceeding.

“For two miles to the eastward of Stewart Harbour, the shore projects, and is rocky and broken, then it retreats, forming a large bay, in which are the Gilbert Islands, and many rocky islets. We passed between Gilbert and Stewart Islands, anchored at noon under a point at the west entrance of the passage, and in the afternoon moved the Beagle to Doris Cove, and there moored her.

“I had decided to build another boat as quickly as possible, for I found it so much the best way to anchor the vessel in a safe place and then work with the boats on each side, that another good one was most necessary. Our cutter required too many men, and was neither so handy, nor could she pull to windward so well as a whale-boat; and our small boat was only fit for harbour duty. The weather on this coast was generally so thick and blowing, as not to admit of any thing like exact surveying while the vessel was under sail: the swell alone being usually too high to allow of a bearing being taken within six or eight degrees: and the sun we seldom saw. If caught by one of the very frequent gales, we might have been blown so far to the eastward that I know not how much time would have been lost in trying to regain our position. These coasts, which are composed of islands, allow boats to go a long distance in safety, and, from the heights near the sea, rocks and breakers may be seen, and their places ascertained, much better than can possibly be done at sea. For building a new boat we had all the materials on board, except prepared plank; and for this we cut up a spare spar, which was intended to supply the place of a defective or injured lower mast or bowsprit. With reluctance this fine spar, which had been the Doris's main-topmast, was condemned to the teeth of the saw; but I felt certain that the boat Mr. May would produce from it, would be valuable in any part of the world, and that for our voyage it was indispensable.

“Profiting by a clear day, I went to a height in the neighbourhood, whence I could see to a great distance in-shore, as well as along the coast, and got a view of Mount Sarmiento. While away from the Beagle, in search of the lost boat, we had enjoyed four succeeding days of fine weather, during which that noble mountain had been often seen by our party. The astronomical bearing of its summit was very useful in connecting this coast survey with that of the Strait of Magalhaens.

“25th and 26th. Mr. Murray went to the S. W. part of the island, taking three days' provisions. Mr. Stokes and I were employed near the ship, while every man who could use carpenter's tools was occupied in preparing materials for our new boat. The rock near here is greenstone, in which are many veins of pyrites. Specimens are deposited in the museum of the Geological Society.

“28th. Weighed, warped to windward, and made sail out of Adventure Passage. I was veiy anxious to reach Christmas Sound, because it seemed to me a good situation for the Beagle, while the boats could go east and west of her, and the new boat might be built. Running along the land, before a fresh breeze, we soon saw York Minster, and in the evening entered Christmas Sound, and anchored in the very spot where the Adventure lay when Cook was here. His sketch of the sound, and description of York Minster, are very good, and quite enough to guide a ship to the anchoring place. I fancied that the high part of the Minster must have crumbled away since he saw it, as it no longer resembled ‘two towers,’ but had a ragged, notched summit, when seen from the westward. It was some satisfaction to find ourselves at anchor at this spot in February, notwithstanding the vexatious delays we had so often experienced.

“As we had not sufficiently examined the coast between this sound and Gilbert Islands, I proposed sending Mr. Murray there with the cutter, while I should go to the eastward, during which time our new boat would be finished.

“1st March. This morning I went to look for a better anchorage for our vessel, that in which we lay being rather exposed, and very small. Neither Pickersgill Cove nor Port Clerke suited; so I looked further, and found another harbourj nearer to York Minster, easier of access for a ship arriving from sea, and with a cove in, one corner where a vessel could lie in security, close to a woody point. Having sounded this harbour, 1 returned to move our ship. Cook says, speaking of Port Clerke, ‘South of this inlet is another, which I did not examine:’—and into that inlet, named March Harbour, the Beagle prepared to go, but before we could weigh and work to windward, the weather became bad, which made our passage round the N.W. end of Shag Island rather difficult, as we had to contend with squalls, rain, and a narrow passage between rocks. The passage between Waterman Island and the south end of Shag Island is more roomy; but there is a rock near the middle which had not then been examined. We worked up to the innermost part of the harbour, and moored close to a woody point, in the most sheltered cove. Finding this to be a very convenient spot for building our boat, and in every point of view a good place for passing part of the month of March, I decided to keep the Beagle here for that purpose. This harbour might be useful to other vessels, its situation being well pointed out by York Minster (one of the most remarkable promontories on the coast), and affording wood and water with as little trouble as any place in which the Beagle had anchored.

“March 2d. The master set out in the large cutter, with a fortnight's provisions, to examine the coast between the north part of Christmas Sound and Point Alikhoolip, near which we passed on the 28th, without seeing much of it. With moderate weather and a little sunshine, he might have been expected to return in a week or ten days. He carried a chronometer and other necessary instruments. Two of the three children, left by their mother at Stewart Harbour, I sent with Mr. Murray, to be left with any Fuegians he might find most to the westward, whence they would soon find their friends. The third, who was about eight years old, was still with us: she seemed to be so happy and healthy, that I determined to detain her [Fuegia Basket] as a hostage for the stolen boat, and try to teach her English. Lieutenant Kempe built a temporary house for the carpenters, and other workmen, near the ship and the spot chosen for observations, so that all our little establishment was close together. The greater part of the boat's materials being already prepared, she was not expected to be long in building, under the able direction and assistance of Mr. May.

“3d. Some Fuegians in a canoe approached us this morning, seeming anxious to come on board. I had no wish for their company, and was sorry to see that they had found us out; for it was to be expected that they would soon pay us nightly as well as daily visits, and steal every thing left within their reach. Having made signs for them to leave us, without effect, I sent Mr. Wilson to drive them away, and fire a pistol over their heads, to frighten them. They then went back, but only round a point of land near the ship; so I sent the boat again to drive them out of the harbour, and deter them from paying us another visit. Reflecting, while Mr. Wilson was following them, that by getting one of these natives on board, there would be a chance of his learning enough English to be an interpreter, and that by his [this?] means we might recover our lost boat, I resolved to take the youngest man on board, as he, in all probability, had less strong ties to bind him to his people than others who were older, and might have families. With these ideas I went after them, and hauling their canoe alongside of my boat, told a young man [York Minster] to come into it; he did so, quite unconcernedly, and sat down, apparently contented and at his ease. The others said nothing, either to me or to him, but paddled out of the harbour as fast as they could. They seemed to belong to the same tribe as those we had last seen.

“4th. This afternoon our boat's keel was laid down, and her moulds were set up. Fuegia Basket* told ‘York Minster’† all her story; at some parts of which he laughed heartily. Fuegia, cleaned and dressed, was much improved in appearance: she was already a pet on the lower deck, and appeared to be quite contented. York Minster was sullen at first, yet his appetite did not fail; and whatever he received more than he could eat, he stowed away in a corner; but as soon as he was well cleaned and clothed, and allowed to go about where he liked in the vessel, he became much more cheerful.

“At Cape Castlereagh and the heights over Doris Cove in Gilbert Island, the rock seemed to contain so much metal, that I spent the greater part of one day in trying experiments on pieces of it, with a blowpipe and mercury. By pounding and washing I separated about a tea-spoonful of metal from a piece of rock (taken at random) the size of a small cup. I put the powder by carefully, with some specimens of the rock—thinking that some of these otherwise barren mountains might be rich in metals. It would not be in conformity with most other parts of the world were the tract of mountainous islands composing the Archipelago of Tierra del Fuego condemned to internal as well as external unprofitableness. From the nature of the climate agriculture could seldom succeed; and perhaps no quadrupeds fit for man's use, except goats and dogs, could thrive in it: externally too, the land is unfit for the use of civilized man. In a few years its shores will be destitute of seal: and then, what benefit will be derived from it?—unless it prove internally rich, not in gold or silver, but perhaps in copper, iron, or other metals.

“5th. This day all hands were put on full allowance, our savings since we left San Carlos having; secured a sufficient stock of provisions to last more than the time allotted for the the remainder of our solitary cruise.

“By using substitutes for the mens' shoes, made of sealskin, we secured enough to last as long as we should want them. I have never mentioned the state of our sick list, because it was always so trifling. There had been very little doing in the surgeon's department; nothing indeed of consequence, since Mr. Murray dislocated his shoulder.

“The promontory of York Minster is a black irregularly-shaped rocky cliff, eight hundred feet in height, rising almost perpendicularly from the sea. It is nearly the loftiest as well as the most projecting part of the land about Christmas Sound, which, generally speaking, is not near so high as that further west, but it is very barren. Granite is prevalent, and I could find no sandstone. Coming from the westward, we thought the heights about here inconsiderable; but Cook, coming from the South Sea, called them ‘high and savage.’ Had he made the land nearer the Barbara Channel, where the mountains are much higher, he would have spoken still more strongly of the wild and disagreeable appearance of the coast.

“6th. During the past night it blew very hard, making our vessel jerk her cables with unusual violence, though we had a good scope out, and the water was perfectly smooth. We saw that the best bower-anchor had been dragged some distance, it was therefore hove to the bows when its stock was found to be broken, by a rock, in the midst of good ground, having caught the anchor. It had been obtained at San Carlos from a merchant brig, but being much too light for our vessel, had been woulded [wound?] round with chains to give it weight: its place was taken by a frigate's stream-anchor, well made and well tried, which I had procured from Valparaiso.* In shifting our berth, the small bower chain was found to be so firmly fixed round another rock that for several hours we could not clear it. Such rocks as these are very treacherous and not easily detected, except by sweeping the bottom with a line and weights. A very heavy squall, with lightning and thunder, passed over the ship this afternoon, depressing the sympiesometer more than I had ever witnessed. Very heavy rain followed.

“8th. In the forenoon I was on a height taking angles, when a large smoke was made by natives on a point at the entrance of the harbour; and at my return on board the ship, I found that two canoes had been seen, which appeared to be full of people. Supposing that they were strangers, I went in a small boat with two men to see them, and find out if they possessed any thing obtained from our lost whale-boat, for I thought it probable she might have been taken along the coast eastward, to elude our pursuit. I found them in a cove very near where our carpenters were at work. They had just landed, and were breaking boughs from the trees. I was surprised to see rather a large party, about fourteen in number, all of whom seemed to be men, except two women who were keeping the canoes. They wanted me to go to them, but I remained at a little distance, holding up bits of iron and knives, to induce them to come to me, for on the water we were less unequal to them. They were getting very bold and threatening in their manner, and I think would have tried to seize me and my boat, had not Lieutenant Kempe come into the cove with six men in the cutter, when their manner altered directly, and they began to consult together. They were at this time on a rock rising abruptly from the water, and the canoes, which I wanted to search, were at the foot of the rock. Under such local disadvantages I could not persevere without arms, for they had stones, slings, and spears, ready in their hands. Lieutenant Kempe and myself then returned on board for arms and more men, for I resolved to drive them out of the harbour, as it was absolutely necessary. Already they, or their countrymen, had robbed us of a boat, and endangered the lives of several persons; and had they been allowed to remain near us, the loss of that part of another boat which was already built would have followed, besides many things belonging to the carpenters and armourer, which they were using daily on shore.

“Another motive for searching the canoes, arose from seeing so many men without women, for I concluded that some of the whale-boat thieves were among them, who, having seen our cutter go to the westward full of people, might suppose we had not many left on board: one boat's crew, as they perhaps imagined, being left on an island, and another away in search of them. They had hitherto seen only merchant-vessels on this coast, and judging of the number of a crew by them, might think there could not be many persons on board, and that the vessel would be easy to take. At all events they came prepared for war, being much painted, wearing white bands on their heads, carrying their slings and spears, and having left all their children and dogs, with most of their women, in some other place.

“Two boats being manned and armed, I went with Lieut. Kempe and Mr. Wilson to chase the Fuegians, who were paddling towards another part of the harbour. Seeing the boats approaching, they landed and got on the top of a rock, leaving the canoes underneath with the two women. From their manner I saw they were disposed to be hostile, and we therefore approached leisurely. Their canoes being within our reach, I told the bowman to haul one alongside that we might search it; but no sooner did his boathook touch it, than a shower of stones of all sizes came upon us, and one man was knocked down, apparently killed, by the blow of a large stone on the temple. We returned their volley with our fire-arms, but I believe without hitting one of them. Stones and balls continued to be exchanged till the cutter came to our assistance. The Fuegians then got behind a rock, where we could not see them and kept close. Their canoes we took, and finding in them some bottles* and part of our lost boat's gear, we destroyed them. The man of my crew who was knocked down by a stone was only stunned, and soon recovered, but the blow was very severe and dangerous. Not choosing to risk any further injury to our people, and seeing no object to be gained, I would not land, though our numbers were much superior, and we had fire-arms. It appeared that the savages knew of no alternative but escape or death, and that in trying to take them they would certainly do material injury to some of our party with their spears, stones, or large knives made of pieces of iron hoops. Remaining therefore with Lieut. Kempe, in the cutter, to watch their motions, I sent my boat on board with the man who was hurt. The Fuegians made their escape separately through the bushes, and were quickly out of sight and reach: we fired a few shots to frighten them, watched their retreat over the barren upper part of the hills, and then went to look for their wigwams, which could not be far distant, as I thought; but after unsuccessfully searching all the coves near us, a smoke was seen at the opposite side of the sound, on one of the Whittlebury islands; so concluding it was made by the rest of their tribe, and being late, I returned on board.

“9th. At daylight, next morning, I went to look for the wigwams, on the Whittlebury Islands, at the north side of the sound: we saw their smoke when we were half-way across, but no longer. The natives had probably seen us, and put out their fire directly, well knowing the difference between our boat and their own canoes, and noticing her coming from a part of the sound distant from the point whence they would expect their own people, and crossing over against a fresh breeze, which a canoe could not attempt to do. The wigwams were entirely deserted, and almost every thing was taken away; but near their huts a piece of ‘King's white line,’ quite new, was picked up; therefore our boat* had been there, or these were some of the people who stole her. For the late inmates of the wigwams we searched in vain—only their dogs remained, they themselves being hidden. Looking round on the other side of that islet, we saw two canoes paddling right away from the islands, though it was blowing a fresh breeze, and a considerable sea was running. Knowing, from the place they were in, and their course, that they were the fugitives from the wigwams, we gave chase, and came up with them before they could land, but so close to the shore that while securing one canoe, the other escaped. From that which we seized a young man and a girl jumped overboard, deserting an old woman and a child, whom we left in order to chase the young man; but he [Boat Memory] was so active in the water that it was fully a quarter of an hour before we could get him into our boat. Having at last secured him, we followed the others, but they had all landed and hidden, so we returned across the sound with our captive. In our way a smoke was seen in a cove of Waterman Island, and knowing that it must be made by those who escaped us yesterday, as there were no other natives there, we made sail for it; but the rogues saw us, and put out their fire. When we reached the spot, however, we found two wigwams just built, and covered with bark; so that there they had passed the night after their skirmish. I would not let any one land, as the Fuegians might be lurking in the bushes, and might be too much for two or three of us on shore,—but left the place. They would think us gone for more boats, as at the former meeting, and would shift their quarters immediately; so by thus harassing them, I hoped to be freed from any more of their visits while we remained in the neighbourhood.

“The bodily strength of these savages is very great (‘York Minster’ is as strong as any two of our stoutest men), which, with their agility, both on shore and in the water, and their quickness in attack and defence with stones and sticks, makes them difficult to deal with when out of their canoes. They are a brave, hardy race, and fight to the last struggle; though in the manner of a wild beast, it must be owned, else they would not, when excited, defy a whole boat's crew, and, single-handed, try to kill the men; as I have witnessed. That kindness towards these beings, and good treatment of them, is as yet useless, I almost think, both from my own experience and from much that I have heard of their conduct to sealing vessels. Until a mutual understanding can be established, moral fear is the only means by which they can be kept peaceable. As they see only vessels which when their boats are away have but a few people on board, their idea of the power of Europeans is very poor, and their dread of fire-arms not nearly so great as might be imagined.

“From this cove we returned to the Beagle. My Fuegian captive, whom I named ‘Boat Memory,’ seemed frightened, but not low-spirited; he eat enormously, and soon fell fast asleep. The meeting between him and York Minster was very tame, for, at first, they would not appear to recognise or speak to each other. ‘Boat’ was the best-featured Fuegian I had seen, and being young and well made, was a very favourable specimen of the race: ‘York’ was one of the stoutest men I had observed among them; but little Fuegia was almost as broad as she was high: she seemed to be so merry and happy, that I do not think she would willingly have quitted us. Three natives of Tierra del Fuego, better suited for the purpose of instruction, and for giving, as well as receiving information, could not, I think, have been found.

“10th. This morning, having been well cleaned and dressed, ‘Boat’ appeared contented and easy; and being together, kept York and him in better spirits than they would probably otherwise have been, for they laughed, and tried to talk, by imitating whatever was said. Fuegia soon began to learn English, and to say several things very well. She laughed and talked with her countrymen incessantly.

“12th. Some evenings, at dusk, I observed large flights of birds, of the petrel kind, skimming over the sea (like swallows), as if in chase of insects. These birds were black, about the size of a ‘Cape Pigeon.’ We tried to shoot one, but did not succeed.”

CHAPTER XXII

Mr. Murray returns—Go to New Year Sound—See Diego Ramirez Islands from Henderson Island—Weddell's Indian Cove—Sympiesometer—Return to Christmas Sound—Beagle sails—Passes the Ildefonso and Diego Ramirez Islands—Anchors in Nassau Bay—Orange Bay—Yapoos—Mr. Murray discovers the Beagle Channel—Numerous Natives—Guanacoes—Compasses affected—Cape Horn—Specimens—Chanticleer—Mistake about St. Francis Bay—Diego Ramirez Islands Climate—San Joachim Cove—Barnevelt Isles—Evouts Isle—Lennox Harbour.

“14th. This morning the master returned, having succeeded in tracing the coast far enough to join our former work, although the weather had been very unfavourable. He met with many Fuegians, most of whom were armed with slings, spears, and cutting weapons made with pieces of iron hoop fastened on a stick. They were very troublesome, especially at night, and obliged him to keep them at a distance. Their respect for a musket was not so great as might have been expected, and unless they saw it tolerably close, and pointed directly at them, they cared not. The boat's crew bought some fish from them, for buttons and other trifles. From forty to fifty men, besides women and children, were seen in one place alone; and many were met elsewhere.

“Mr. Murray penetrated nearly to the base of the snow-covered mountains, which extend to the eastward in an unbroken chain, and ascertained that there are passages leading from Christmas Sound to the large bay where the whale-boat was stolen; and that they run near the foot of the mountains. He also saw a channel leading farther to the eastward than eye-sight could reach, whose average width seemed to be about a mile. He left the two children in charge of an old woman whom they met near the westernmost part which his party reached, who appeared to know them well, and to be very much pleased at having them placed in her care.

“15th. Raining and blowing:—as usual, I might say. When it moderated I left the Beagle, and set out in a boat with Mr. Wilson (mate), taking a fortnight's provisions; though I hoped to be again on board in less than ten days, by which time our new boat would be finished, and Mr. Stokes, as well as Mr. Murray, would have laid down his last work. My object was to go eastward towards Indian Sound and Nassau Bay, but the weather soon stopped our progress, and obliged us to put into a small cove on the west side of Point Nativity, where we hoped to get shelter from the increasing wind, though not from the rain, which poured down in torrents. The cove proved to be much exposed, but we staid there till daylight on the following morning, when we pulled out, and round the point to the eastward, gladly enough, for we had been in a bad berth during the night, exposed to wind and rain, besides swell. We ran along the land, with a moderate westerly wind, stopped for a time near Cape Rolle, the point of land next to Weddell's ‘Hope Island;’ and in the evening went into some openings among the adjacent islands.

“17th. At daylight we set out again, and ran along-shore with a fresh west wind, crossed the mouth of a bay which seemed likely to afford shelter, but did not then delay to look at it closely. Soon after noon we passed Weddell's ‘Leading Hill,’ which is a very singular double-peaked height, conspicuous from a long distance, and remarkable in every point of view. Between it and Black Point (a projecting craggy rock) lies a bay or sound, which appears to extend some distance northward. This part of the coast is bad for vessels to close with, being much broken, and having several rocky islets scattered near it; but two miles off shore there is no danger. Having found a secure cove near Leading Hill, we landed, and the men set up our tent, while Mr. Wilson and I ascended the heights to look round. The wind soon freshened to a gale, and made us rejoice at having reached a sheltered place.

“18th. The whole of this day was lost by us, for it blew a strong gale with continual rain. Collecting limpets and muscles—cutting wood—and drying our clothes on one side by the fire, while the other got wet, were our only occupations.

“19th. Still a strong wind, but less rain. Between the squalls I obtained a few sights of the sun, for time, and at noon a tolerably good set for latitude. Being then better weather, and likely to improve, we crossed in the boat to Leading Hill, and from its summit took the necessary angles. It was very cold and windy, but we effected all that was then required.

“20th. Decamped very early and ran across Duff Bay, towards Henderson Island, with a moderately fresh breeze off the land; and as my object was to obtain a good view and a round of angles from the summit of a height on that island, I passed Weddell's Morton Isle, Blunder Cove, &c. without stopping, and reached the north end of Henderson Island soon enough to get sights for time. From that spot we went a short distance to a cove, where the boat might remain during my absence on the hill, observed the latitude, and then ascended. Before we were half-way up, a squall came on from S.W. and increased rapidly, but having ascended so far, I was not disposed to turn back, so we pushed on and reached the summit; yet, when there, I could not use a theodolite, on account of the wind. Towards the east I could see a long distance, to the farthest of the Hermite Islands; but towards the west the view was obscured by haze; so leaving the instruments, I hastened down to the boat and found her safe, though she had been in great danger. By this time the wind had moderated, and before dark we measured the distance between the morning and noon stations: that from the latter to the summit of the hill I had measured, when at the top, by a micrometer. We then passed round the north end of the island, and in the dark searched the east side for a resting-place, which after some time was found.

“21st. A fine clear day enabled me to make the necessary observations, and I then went up the height and succeeded in obtaining a distinct view of the Diego Ramirez Islands. As this hill is distant from them between fifty and sixty miles, I felt sure of getting a good cross bearing from the south end of the Hermite Islands, distant from them, as I then thought, only about forty, and thus fixing their position.

“New Year Sound appears to be a large body of water extending towards the N.W., with a multitude of islands scattered about it. From its east side the land trends away towards a point which is curiously peaked, like a horn, and which I supposed to be the western point of Nassau Bay.*

“22d. We had hardly left our cove, when steady rain set in; however, we went across towards New Year Sound, sometimes favoured by the wind, but could do little. As far as I saw the day before, the snowy chain of mountains continued to the eastward, therefore I had little hope of finding a body of water in the interior of Tierra del Fuego, about the head of Nassau Bay. About noon we were near Weddell's ‘Indian Cove,’ but the weather being thick I did not recognise it, so we stood up the sound with a fresh breeze from the W.S.W. I soon found that it led only to the north and west, and probably communicated with some of the passages which Mr. Murray saw leading to the eastward from the neighbourhood of Christmas Sound. Towards the north and east I had already noticed a long range of mountains. Concluding therefore from what I then observed, and from views obtained from the heights, that no passage leads from this sound direct to Christmas Sound, and that to return to the Beagle I must go part of the way by the sea-coast, or else go round, by a series of intricate passages, to the places which Mr. Murray had seen in the cutter; I preferred the coast, as a second view of it would be of use, while a traverse among the islands could not be very beneficial.

“Putting about, we returned down the sound, the breeze still allowing us to sail fast. We closed the western shore to look for Indian Cove, and, as the weather had cleared up, found it without difficulty. It is not so good a place as I expected; for except at the inner corner close to a run of water, I found only rocky soundings. The few casts of good ground were so close to the shore that the place can only be considered fit for a cutter, or small craft, which could lie quite close to the land. This cove is, in my opinion, too far inland to be of general use; and an anchorage under Morton Island would be far preferable for a vessel arriving from sea. We found an empty North American cask, apparently left that season: on a height near the cove there was a pile of stones we had not time to examine: and much wood appeared to have been cut down lately by the crew of some vessel. We saw several wigwams, but no Indians. That night we stopped near the S.W. point of the sound, close to Gold-dust Island.

“23d. After examining the cove, in which we passed the night, and taking observations, we crossed Duff Bay, towards Leading Hill. I wished to have seen more of a promising bay on the east side of Morton Island, where I thought there was good anchorage, but could not afford time, as it was probable that we should be delayed in our return along this exposed part of the coast against the prevailing winds. There is a considerable tide between Morton Isle and the point next to Golddust Isle. The flood comes from the westward, about one knot, or at times two knots, an hour. With the ebb it is nearly slack water, or perhaps there is a slight tendency towards the west; and such appears to be the case all along this coast, from Christmas Sound. We reached Leading Hill late in the afternoon, although the wind had increased much and was directly against us: at night it blew a gale from the westward.

“24th. A strong gale prevented our moving, or making any beneficial use of our time.

“25th. Still blowing very fresh; but I thought we could pull round into the next bay, and there do some good by planning the harbour, &c., although we might get no farther for some days. From the season, the state of the sympiesometer, and the appearance of the weather, I did not expect any favourable change until about the end of the month. The sympiesometer was my constant companion: I preferred it to a barometer, as being much more portable and quicker in its motions. By great exertion on the part of the men, for it required five hours' hard pulling, we got round a headland into the next bay, a distance of only four miles. It rained great part of the time, and in the afternoon poured steadily, but we succeeded in finding a sheltered spot for our lodging, and soon put ourselves into somewhat better plight than we had been in during the greater part of the day, the men having been constantly soaked through, and their hands quite numbed with cold and wet. I was disappointed by this place; the various coves were sounded, without getting bottom with twenty-five fathoms of line; and I could find no anchorage without going further up the inlet than would suit any vessel running in from sea for a temporary shelter.

“26th. A strong gale prevented our going outside, but in hopes that there might be an inland passage I set out to look for one. Having pulled and sailed about six miles up the inlet, we reached its termination, and thence returned to our bivouac. There seemed to be an opening into Duff Bay not previously seen, which would have saved us some time and trouble had we known of its existence.

“27th. The gale continued with more or less violence, and during the greater part of the day we were occupied in gathering limpets and muscles, as a stock of food in case of being detained longer than our provisions would last. Shooting did not succeed, because the sea-birds were very wild and scarce. I regretted that there was no harbour in the inlet which could be planned during our stay. Every cove we could find had deep water, and so rocky a bottom that we found difficulty in securing even our small boat; for this continued gale raised so much swell that we were kept on the alert at night to shift her berth as often as the wind changed.

“28th. This day, and the preceding night, the wind was exceedingly violent, from N.W. to S.W., but generally southward of west. In pulling across the cove to get limpets, the squalls at times forced the oars out of the men's hands, and blew them across or away from the boat. Much rain fell during most nights, but after sunrise it generally ceased; sometimes however the rain poured down by day as much as by night.

“I here saw many seals teaching their young ones to swim. It was curious to see the old seal supporting the pup by its flipper, as if to let it breathe and rest, and then pushing it away into deep water to shift for itself.

“29th. This morning, with better weather, we sailed very early in hopes to get round Black Point; the wind being moderate promised well, but, with the sun, it rose again. However, we tried hard for about six hours, during four of which I hardly hoped to succeed, for it blew strong, and the tide race was dangerous: but before evening we gained the sheltered part of Trefusis Bay. The men were on their oars from five in the morning till four in the afternoon, and, excepting two rests of a quarter of an hour each, pulling hard all the time. We landed in a sheltered spot, about half a mile within the entrance of a passage which leads from Trefusis Bay to Christmas Sound. Our fatigue and thorough drenching, by sea and rain, was then little cared for, having gained our point, and being only a day's pull from the Beagle.

“I had seen along this passage from Christmas Sound, as well as from Leading Hill, and rejoiced to get into it, for the outer coast is a wild one for a boat at any period of the year—and this was the month of March; about the worst time.