The Galápagos Islands:

A History of their Exploration

Joseph Richard Slevin

Note: Selected Excerpts; in Table of Contents, red text indicates a link; black indicates text not included here.

Dedication

To Robert Cunningham Miller, Director of the California Academy of Sciences, whose interest in the project made its completion possible, this volume is gratefully dedicated

Preface

It is not the intention of the author to compile in the present work a complete bibliography of Galápagos literature, but rather to treat of the history of the islands from the time of their discovery to the present, bringing to light historical events and documents unknown to many Galápagos students as well as giving an account of some of the men and ships connected with their history.

A selected bibliography, however, is appended for those who wish to make a serious study of the flora and fauna of these islands, or for those who merely wish to read of the numerous explorers and visitors before and after the memorable voyage of the Beagle.

Probably no other group of islands in the world has been the object of so much intensive study by the world's most distinguished scientists. It was amongst these now famous islands that Charles Darwin first formed his ideas as to the origin of species, and where he started on a career that made him one of the greatest naturalists of all time.

The Galápagos have been one of the principal fields of endeavor of the California Academy of Sciences since its original expedition there in 1905-06, and its collections from the Galápagos Archipelago are unsurpassed.

To enumerate all those who have assisted in compiling these data would make far too lengthy a list and to these my thanks are due. There are, however, those to whom I am especially indebted and without whose help the project would have been impossible: The Reverend Padre Emilio del Sol, of the Church of Santa Maria del Mercado, Berlanga, Spain, furnished the photographs of the burial place and wood carving of Fray Tomas, the discoverer of the Galápagos; Captain H. J. Hennessy and Commander W. E. May of the Royal Navy on duty at the Admiralty were most helpful, as well as the Imperial War Museum and the Maritime Museum which supplied naval photographs and prints; the British Museum Library allowed the use of old maps and diaries and the Public Records Office the data from the various old logs and letters; Mr. H. W. Parker, of the British Museum of Natural History, extended many personal courtesies; Rear Admiral Francisco Benito Perera, of the Spanish Navy, and Captain Proctor Thornton, U.S.N. (Ret.), have been most helpful in securing data regarding the early Spanish ships; the Pennsylvania Historical Society very kindly allowed the use of the Feltus diary; Dr. Paul Chabanaud, of the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, secured the reports of the French vessels of war, Le Genie and Decres, from the French Admiralty; Dr. F. X. Williams, formerly with the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association, sent much information regarding the early whalers. Also, I wish to thank especially Miss Veronica Sexton, Librarian of the Academy, who was most solicitons in attending to many requests, and Mrs. Lillian Dempster, of the Department of Ichthyology, for translating the many Spanish letters connected with the research.

Last, but not least, I feel deeply indebted to Mrs. Barbara Gordon, of the Academy's television staff, who so painstakingly typed the manuscript.

The Author *

* [Joseph Richard Slevin, for more than fifty-three years associated with the California Academy of Sciences in its Department of Herpetology, passed away February 15, 1957, in his seventy-sixth year. He first visited the Galápagos Islands in 1905 as a member of the Academy's Galápagos Expedition. From that date until the time of his death, he maintained an active interest in those islands and published a number of scientific and popular papers about them. The manuscript for the present paper was completed shortly before his death.—Editor.]

The Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Archipelago, or Archipielago de Colón as it is called by the Government of Ecuador, was annexed by that country on February 12, 1832. The history of these islands remained more or less obscure to the world for many years after their discovery as they had no strategic value in the scheme of events until the construction of the Panama Canal. Then at once they became of the greatest importance to the United States as a base for the protection of that waterway in time of war, and were used as such in World War II. Any mention of a plan to lease or purchase them by the United States immediately brought a storm of protest from all Latin America and it was impossible to come to any terms with the Government of Ecuador for permanent occupancy.

The archipelago, consisting of some fifteen islands and numerous islets and rocks, extends from Latitude 1°40' N. to 1°36' S. and from Longitude 89°16'58" to 90°1' W., the nearest point to the mainland being Mt. Pitt on Chatham Island, which is 502.5 miles N. 87°50' W. of Marlinspike Rock, Cape San Lorenzo, Ecuador. The equator passes through the northernmost volcano of Albemarle Island.*

* [The author has used the English names for islands and localities throughout his manuscript which was prepared from the English viewpoint and is published in connection with the Darwinian Centennial year of 1959. Most of these names are not official inasmuch as they have been replaced with Spanish names by the Government of Ecuador. See pages 25-26 for a list of alternatives.—Editor.]

The islands themselves are in reality immense lava piles projecting out of the ocean, some with perfectly formed craters, and there are hundreds upon hundreds of minor ones together with fumaroles and vents scattered over the landscape. Great lava flows extend from the crater rims to the sea. These, the most striking features of the landscape, vary greatly, some being composed of huge black or brown slabs that have the appearance of age, while others are rough, black boulders that appear to be of recent origin, so much so that one would think they had hardly cooled.

(balance to follow)

Description of the Islands

In May, 1932, Captain Garland Rotch of the yacht Zaca, while on the Templeton Crocker Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, made two sketch surveys of anchorages not yet charted. One of these was on the northeast side of Narborough Island and he called it California Cove. The other was Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island, locally known as Puerto President Ayora, although Academy Bay is its official name.§

§ The settlement (now, city) is now known as Puerto Ayora, while the bay it faces was, and still is, Academy Bay (Bahía Academy).

Water

Introduced Animals

Of late years, owing to the activities of tuna boats and various yachts which have called at the islands, it is difficult to tell what domestic animals have been introduced and on what islands. It is known, however, that rats occur everywhere and that with the exception of pigs and cats on Indefatigable, which are a comparatively late importation, the islands listed have been inhabited as follows:

| Island | Burros | Cats | Cattle | Dogs | Goats | Pigs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albemarle | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| Barrington | ■ | |||||

| Charles | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Chatham | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| Hood | ■ | |||||

| Indefatigable | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| James | ■ | ■ | ||||

| South Seymour | ■ |

Cartography

The position of the Galápagos was fairly well known to the early navigators. (balance to follow)

Fig. 9. Map of the Galápagos Islands with the principal islands and localities named. Minor islands, rocks, and other localities are indicated by number as follows: §

|

|

|

§ Each underlined island and rock name is a link to this site's Table of Island Names which provides further details about that name.

The Galápagos “Post Office”

Unique among post office on the shores of the Pacific is the one at Post Office Bay, Charles Island, in the Galápagos Archipelago. This “post office,” a barrel nailed to a post, was doing an active business as far back at [sic, as] 1794, when the Congress of the United States passed the first laws for the management of the postal service, and even though times have changed with unbelievable rapidity and its services are no longer necessary, it is still functioning.

Who nailed up the first barrel is Post Office Bay, and when? No record has yet turned up. Perhaps it was in some long-lost ship's log. Captain James Colnett, Royal Navy, went to the Galápagos in the year 1793 on board the merchant ship Rattler to look into the possibilities of whaling in those waters. As far as can be ascertained, he made no mention in either his diary or his log of erecting a post office, though it is marked on his chart which is dated 1793. British whalers were in the Pacific earlier, the whaler Amelia, Captain Shields, sailing from London for the Pacific in 1787. It is possible, therefore, that some British whaler set it up and the Captain Colnett found it on his arrival, though there seems to be no proof that such is the case. §

§ In fact, Colnett did not visit Post Office Bay, and the barrel does not appear on the chart on Aaron Arrowsmith's Chart of the Galapagos (1798 edition) which appeared in Colnett's Voyage …. The “Post Office” notation was added to the chart in 1820, presumably based on information found on a chart drawn by John Fyffe in 1817.

In this modern world where time and distance have been reduced to insignificance, we are accustomed to sending letters across the seas in a few days by fast ships or by air in a few hours. One hundred years ago, or more, when the whalers of New England made cruises of one, two, or even three years in quest of the sperm whale or cachalot as they called it, things were quite different. It was then that the “post office” on Charles Island was in its prime, used by the whalers cruising the Galápagos waters— their best way of sending word to the folks at home, even though it may have taken a year or more for a letter to reach its destination.

It was customary for a homeward-bound whaler to call at Post Office Bay if possible, pick up the mail, and carry it to her home port. Eventually, through the courtesy of merchants and by devious ways, it would get to the families and friends of the men who have trusted their letters to a barrel on a lonely beach in the Pacific.

Of historical interest it is that, during the war of 1812, Captain David Porter, commanding the U. S. frigate Essex, used the “post office” staregically. He states in his journal:

In the morning I stood to the westward, with a pleasant breeze from the east, which run us, by two P. M., as far as the harbour of Charles Island. On arriving opposite to it, we could perceive no vessels; but understanding that vessels which stopped there for refreshments, such as turtle and land tortoise, and for wood, were in the practice of depositing letters in a box placed for the purpose near the landing-place, (which is a small beach sheltered by rocks, about the middle of the bay,) I despatched lieutenant Downes to ascertain if any vessels had been lately there, and to bring off such letters as might be of use to us, if he should find any. He returned in about three hours, with several papers, taken from a box [Note: box, not barrel] which he found nailed to a post, over which was a black sign, on which was painted Hathaway's Postoffice.

Through the years, of course, the barrel, which was marked “Post Office,” had to be replaced—when the hoops rusted the case would fall apart. Now and then a box of some sort would replace the barrel. Various vessels took on the repairing and replacing of the beach-side mailbox, but chiefly British men-of-war going to station at Esquimault § or en route home to be paid off.

§ At the southern tip of Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

On October 4, 1905, the expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Island [sic, Islands] visited Port Office Bay and found the barrel in fair condition. The hoops were somewhat rusted but holding together. An inscription on it read: “Erected by HMS Leander.” Crews of various vessels calling had painted or carved the names of their ships on the barrel. Among them were His Majesty's ships Virago and Amphion, the French cruiser Protet, the USS Oregon, and the USFS [sic, USS or USFC] Albatross.

A member of the Academy's expedition mailed a letter which was afterward found to have been delivered just a year to the day after it was dropped into the barrel. It was picked up by the British yacht Deerhound, finally reaching the office of the Postmaster General in Washington. The rust from the barrel hoops had obliterated the address so that only the surname of the addressee and the city were legible. Nevertheless, the Post Office Department delivered the letter safely.

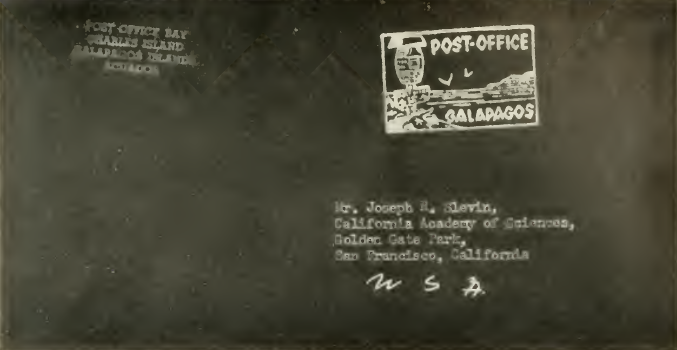

Fig. 21. Envelope addressed to the author and mailed from the Barrel Post Office on Charles Island.

A letter to mailed to the writer on January 3, 1932, arrived about a month later, having been picked up by Vincent Astor's yacht Nourmahal. § This was brought to Papeete and came up on the regular mail steamer. Service has improved somewhat in the last few decades.

§ A potential mix-up here: The return address and postmark illustration were those used by Margret Wittmer; The barely visible rectangular sign beneath the barrel was placed there by the crew of the Polish ship Dar Pomorza on December 14, 1934, and therefore the envelope was placed in the barrel after that date. Astor's Nourmahal visited Galápagos in 1930, 32, 33, 36 and later, but not in 1934. Since Slevin's text was edited and published posthumously, it's possible that Figure 21 is not the envelope containing the letter he mentioned, a point supported by the absence of any indication that this envelope was subsequently posted in Papeete.

Shipwrecks

(Single paragraph excerpt, with link to Porter's text)

Throughout the years, many vessels have left their bones upon Galápagos shores. When Porter was cruising along the Albemarle coast in search of the enemy, he sighted the wreckage of a vessel within five miles of Point Christopher. The shore was covered with what he took to be barrel staves, which led him to believe the vessel was a whaler, but the surf was too high to attempt a landing and he could not be certain whether the wreck was that of a British or American vessel.