Drømmen om Galapagos

Stein Hoff

Part IV

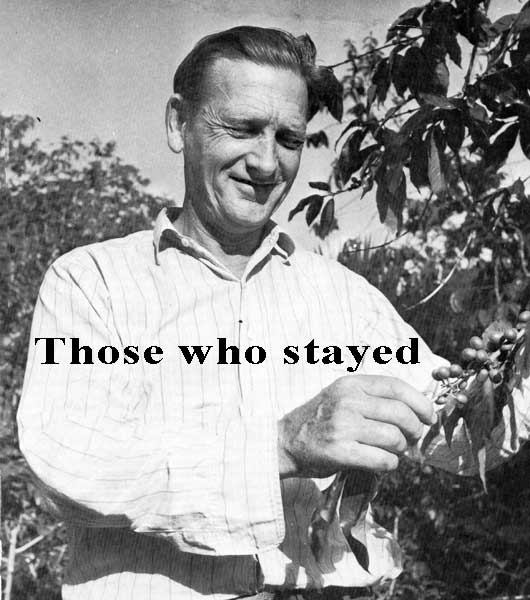

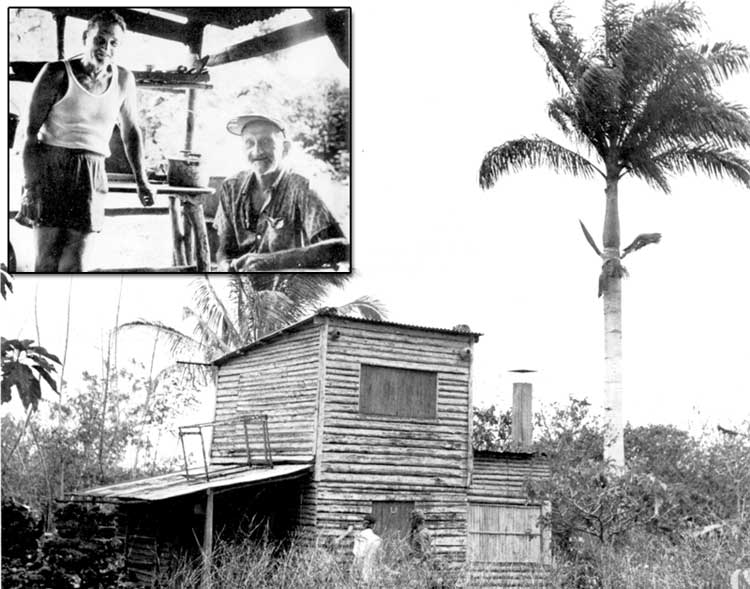

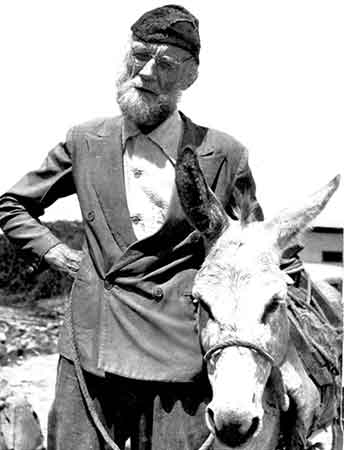

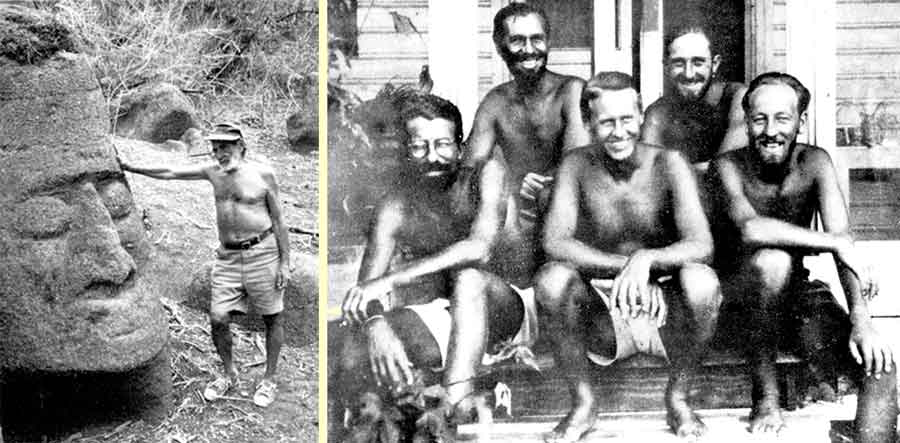

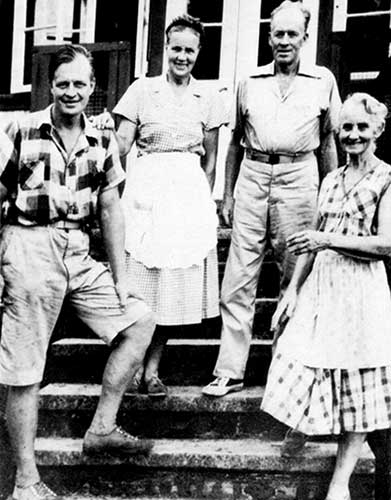

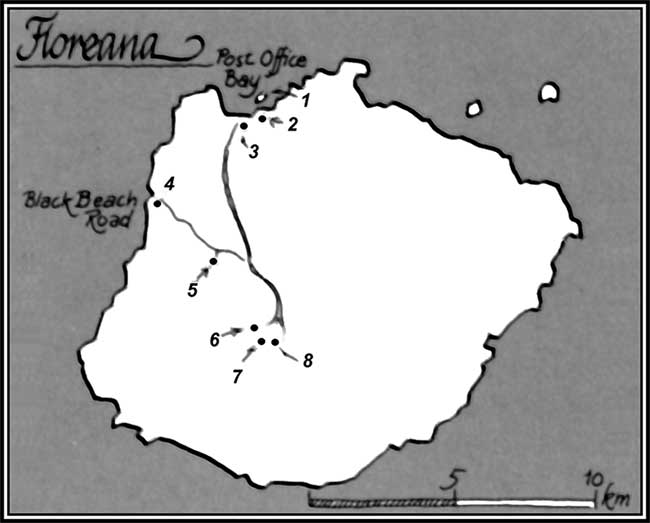

For many years Gordon Wold was Galápagos' third largest supplier of coffee, and was honored with the title “King of Coffee.” Photo courtesy of Miriam Brekke, Porsgrunn.

“…about 75% happy with life”

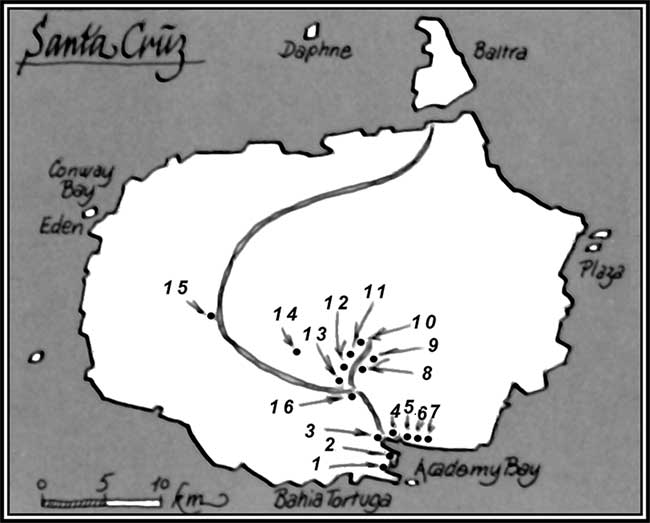

Gordon Wold from Porsgrunn, and Kristian Edvardsen from Stampa farm in Hedrum directly north of Larvik, were the only ones of the Ulva expedition who never wavered in their belief that Santa Cruz offered a good living.

Kristian soon changed his surname to Stampa. In Spanish there are problems in pronouncing “s” at the beginning of a word, so he was usually called “Estampa,” not inappropriate as he thereby retained the “E” for Edvardsen, his middle name.

For several years Stampa and Wold kept together through thick and thin, and depended on each other in their fight for survival. On the beach, each lived in one of the small houses located behind the factory, but “arriba” (in the highlands) they took joint possession of a house at Fortuna. It was the house that was first built for Anders Rambech and Sigvart Tuset, who at that time were responsible for farming on the island, and the same house that “Pig Johansen” inhabited prior to his departure.

During the most sparsely populated period in 1929-30 there were rarely more than three people on the island: the two Norwegians and the Ecuadorian Elias Sanchez. Sanchez was the only one of the original workers who lived on the island when Ulva arrived in August 1926. He told them that he had been on Santa Cruz since 1917, but said nothing about his past. Probably he was one of the political prisoners who was deported to the islands to be used as free labor.

When the human population on Santa Cruz slowly but surely began to increase, it was because of an influx of north-European settlers. They came, as did many before them, driven by an urge for adventure and the hope of finding both a Pacific paradise and a place where they could earn a living. The stark realities made only a few stay longer than a couple of months.

One who held out for a long time was the Danish-American engineer, R. H. [Rudolph Hother] Ræder. He possessed what, regrettably, is most important for success whether in Galápagos or other places in the world, a good supply of cash. Consequently there was also work for others, as Ræder wanted a nice house at the beach for himself and his wife. He had several small huts built for his workmen, as well as a large storehouse in which, among other things, bacalao could be protected from flies and rain. After futile attempts to get the canning factory operational, Ræder also switched to bacalao production, especially before Lent. For this purpose he needed a crew to fish for him.

In addition to fishing, the illegal sale of living tortoises was the colonist's surest source of income. Almost without exception the clients were sailors aboard ships and yachts. Even then tortoises were a protected species and therefore could not legally be sent to Guayaquil. On the local black market in Galápagos there was a good price for the oil rendered from tortoise fat.

One of the men who worked for Ræder was the Norwegian, Ewald Formo, who first came to Galápagos aboard Albemarle but early on moved to Guayaquil.

When Paul Bruun died in the Isabela accident, it was Arthur Worm-Müller's turn to move from Casa Matriz on Floreana into the empty factory in Academy Bay. He also tempted his wife, Hilda, to try out living for a time on the island. The governor appointed Worm-Müller to the unpaid position of the island's comisario—a kind of deputy representative.

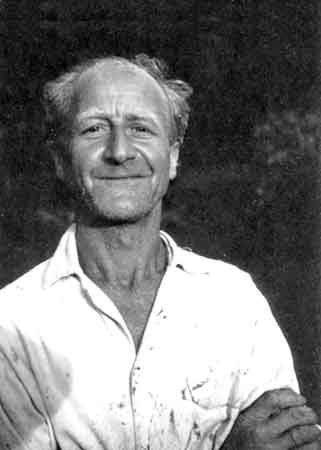

Arthur and Hilda Worm-Müller, Santa Cruz, 1936. Photo courtesy of Rolf Blomberg, Quito.

In the Fall of 1931, about the same time that Worm-Müller settles on his third Galápagos island (he had previously resided on San Cristóbal as well as Floreana), the relationship between Stampa and Wold comes to an end. They have stayed together nearly day and night for five years and are now tired of each other.

The two agree to share equally their common property, and they do it literally. The cultivated land on Fortuna is partitioned with fences into two parcels of exactly the same size, and the house is sawed in half down the middle. Stampa transports his portion down to the beach. For many years, Wold's house at Fortuna had only mosquito netting on the exposed side.

Luckily, Stampa's 24-ft Falcon was spared from subdivision!

A factor contributing to the old friends going separate ways was the population increase on the island, thereby lessening their dependence on each other. Trygve Nuggerud (it is still more than a year until the Baroness arrives in Floreana) moves from San Cristóbal and settles on Santa Cruz with his wife María and boat Dinamita. Now there are three fishing groups on the island: Stampa's, Ræder's and Nuggerud's. Each group employs between 2 and 6 local Ecuadorian fishermen.

In addition, the 54 year old Captain Herman H. Lundh arrives from Oslo to explore the prospects on Santa Cruz. He and Wold, who now concentrate on cultivating coffee, become good friends. They consider purchasing a larger boat for use in fishing and transport between the islands and the continent.

When Wold and Stampa separated, their house at Fortuna (later renamed Bellavista) was divided down the middle. Wold was a hard worker, but he had no enthusiasm for house maintenance. Captain Herman Lundh also considered the house good enough when he moved in and lived there from 1938 to his death in 1947. Lundh, to the left, Wold to the right. The large leaves belong to the important tuberous plant otoya. Photo courtesy of Jacob Lundh, Oslo.

Worm-Müller is a faithful correspondent. A letter to his brother Jacob in the Spring of 1932 gives a contemporary impression of life in Santa Cruz:

“A while ago we sailed to Floreana to pick up my roofing sheets. As cash is scarce, I paid Stampa with 20 of the sheets. I sold some to the Dane and kept 20 for myself. The crossing to Floreana was beautiful. We sailed all the way. It took 7½ hours, which is a record time. Stampa removed the sheets and I carried them down to the beach. Believe me, it is quite a sight now, with lots of removable items missing, as is to be expected. Stampa made a trip to the highlands and killed an ox. It required two trips to bring the carcass to the beach. I cut it up for drying and salting. We stayed there for four days but should have remained at least one day longer because part of the meat that we hung up to dry did not hang long enough. Half of it has become spoiled by maggots. The salted portion was fine and we still have some left.

“One day we went tortuga (sea turtle) hunting in the big bay where they are plentiful. Stampa, Formo, a Norwegian who works for the Dane, and I. It took 1½ hours to go there by motorboat. We were rather late for catching. Well, we entered, anchored the boat and jumped into the dinghy. One man at each end of the dinghy and I at the oars. The trick is to arrive directly over a tortuga as it lays on the bottom, but the water must not be deeper than a man can stand in. When we find such a place, one man jumps head first into the water, trying to grab the turtle by the neck or one of the flippers. Provided he gets a good hold, the other man jumps out to assist and ties a rope around the turtle. With that accomplished the turtle is towed to the larger boat and hauled aboard; then we go for more.

It is great fun watching, and the boys really enjoy the sport. Water sprays all around the three of us, and one sees nothing but a big wrestling lump.

“We got three turtles, large beasts, and had to leave because the tide was very low. We got out alright without having touched bottom more than once, and then only lightly. The surf was big, the bow of the boat was rising up and crashing down; I was glad it was not my boat.

“The following day we boiled the fat which yielded 25 litres (6.5 gals.), enough for some weeks to come. The stench was hellish.

“Initially I couldn't eat food that was fried in it, but now I can because we have nothing else. However, the fat of the tortoise (land turtle) tastes something like olive oil and is really excellent.

“Here there is a scarcity of matches, which is annoying. I can only smoke when the sun is shining, I have to use a magnifying glass…

“…I have 45 sucres to buy merchandise in town. Get what I need for this amount. I had a wild hope of buying a pound of butter, but that amount of cash is insufficient. Butter is considered the greatest of luxuries, you understand, that is why I have such a craving for it.

“Tobacco cannot be cultivated down here as an insect devours all the leaves.

“We were recently on a trip to San Cristóbal. The Dane paid for the fuel as Stampa had no more. The cruise took 11 hours by motorboat. There was mail there for some but none for me. I bought 20 eggs. Believe me, they were delicious, another luxury. They cost 10 centavos (1 sucre=100 centavos) each. I feel I get most out of them when prepared as eggnog. Incidentally, not much happens here, it's a life mostly in peace and quiet. I'm about 75% happy with life, and who could ask for more in these hard times?…”

When provisions from Guayaquil were typically delayed or non-existent, visiting ships and sailors gave valuable assistance to the Norwegians. Here aboard the Mary Pinchot in 1929 are, at left, Governor of Pennsylvania Gifford Pinchot and Kristian Stampa. Fourth and fifth from the left are Trygve Nuggerud and Erling Jenssen from Trondheim. Photo from Pinchot's book To the South Seas.

In 1932, Anna and Jacob Horneman also return to “Villa Villnis” (“Wilderness House”) after an absence of three years. The name of the house is now very appropriate. It is so overgrown that they have difficulty in finding it.

Meanwhile, their youngest son, Christian, who was born in Norway, stays behind with Anna's parents in Lillesand, but four year old Robert accompanies them. In August of the same year, Robert gets a playmate when Herman Lundh's wife, Helga, and their son Jacob, arrive from Oslo. Jacob is also four years old.

Herman Lundh and Gordon Wold have now joined in a business venture and purchased the sloop Santa Inez. By so doing they revive Olav Eilertsen's old dream of a freighter to the continent, owned and managed by Norwegians. Up to now the islanders' biggest problem has been the unreliable export facilities for bacalao and the irregular supply service from outside. The old Manuel J. Cobos has been taken over by the local government and rechristened San Cristóbal. This has actually improved connections with the continent as far as mail and passenger traffic is concerned, but in return the price for freighting has increased threefold—to the great despair of the bacalao fishermen.

The one-masted Santa Inez is able to carry a load of 60 tons, needs only a crew of two and should be ideal for the colonists' needs.

With the number of inhabitants on the island into two digits, including women and children, a new engine in his Falcon, and improved facilities both for people and bacalao, Stampa considers that it is time to invite his fiancée, Alvhild Holand, to Santa Cruz.

The original plan was that she should join her Kristian as soon as Ulva colonists had made a decent start. But with all the problems arising, he felt that Santa Cruz was no place to raise a family. Not until now— seven years later.

He writes to Alvhild, who lives in Kodal near Sandefjord. She arranges passage aboard the Haugesund-registered ship Marie Bakke, and arrives in Guayaquil in April 1933. The man who greets her in Guayaquil is quite different from the 25-year-old who left Norway in 1926. Kristian Stampa is now tanned like a native, tall, slender and wiry. He has matured in those seven years and is marked by the struggle for survival—a process that has inflicted both sickness and privations. The lean man is emaciated as a result of recent attacks of dysentery. Once in 1929 he was so sick that Bruun took him aboard “Cobos” to Guayaquil to get him to a physician. Together with Wold he also has had his share of shipwrecks, but has survived, thanks to his craftiness and toughness.

Alvild and Kristian marry in Guayaquil—first in English by an American clergyman and afterwards in Spanish by a local judge. Ecuadorian law requires a civilian marriage ceremony. Alvhild is not versed in any of these languages, but she trusts her Kristian.

The sloop Santa Inez was to fulfull the old dream about a freighter run by Norwegians. Instead, it was mostly hard work, expenses and repairs. After two years Lundh and Wold gave up. The photo was taken in Guayaquil in 1934 when Jens Moe (seated behind the anchor chain) returned to Galápagos. To his left is the Swedish author Rolf Blomberg and Wold is seated behind and to the right of Moe. Photo courtesy of Jacob Lundh, Oslo.

Alvhild Stampa becomes a housewife on Santa Cruz—and really thrives. Her ability to cope with and adapt to her environment is no less than Kristian's. She soon knows all the unfamiliar vegetables, she fries platanas in tortoise oil and bakes sourdough bread in her wooden stove. When she becomes pregnant, she wants to give birth on Santa Cruz. The nearest midwife is on San Cristóbal, the nearest physician in Guayaquil on the continent. Kristian fetches the midwife, and on April 12, 1934, Anne Carmen Dolores Stampa is successfully delivered. As a result, she is the first baby of European colonists born on the island. [As far as we know, this was the first birth ever on Santa Cruz. Others had gone to San Cristóbal.]

With a little one in the house, milk is needed. Hence, Kristian sails to the island of Santiago where there are herds of feral goats. He catches several females with kids and brings them back to Academy Bay.

After receiving water, corn, and bananas, the animals soon become so tame that they return home each morning to get water and be milked. Stampa also makes a fitting cradle for Anne—the carapace (upper half of the shell) of a full-grown Galápagos tortoise!

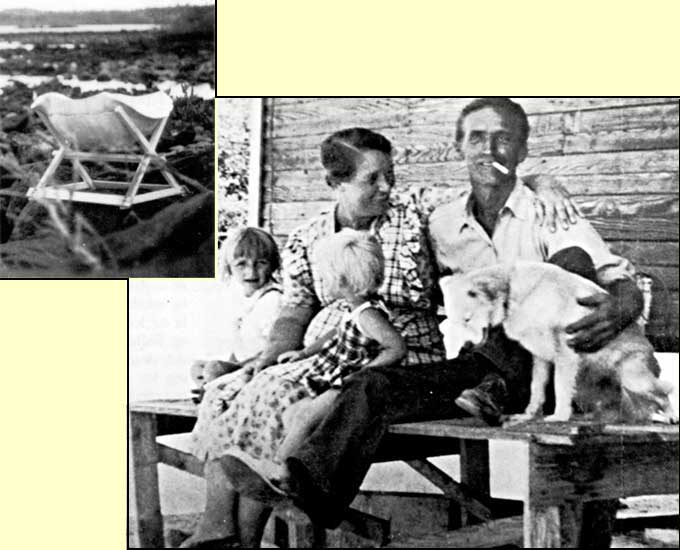

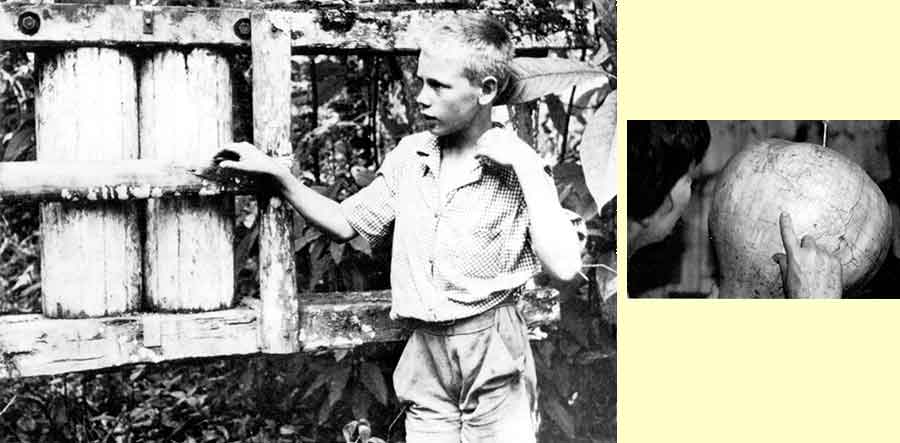

Happy days on Santa Cruz. From left, “Friedelpeter” Horneman, Alvhild with Marit on her lap, and Kristian Stampa with their dog “Topsy”photographed at “Arena Blanca” in 1944. Inset shows the cradle which Kristian Stampa made out of a tortoise shell in 1934. It lay well hidden and forgotten in a shed next to “Arena Blanca” until May, 1985. Photos courtesy of Jacob Lundh and Andrew Fraser (inset).

The New Commissioner

For a while now the Galápagos gods have been kind. But after this sunny interim, drought and misery sets in with the most dramatic year in the islands' history. The Baroness and Philippson disappear; Lorenz, Nuggerud, Pasmino and Ritter die.

A German family settles on Santa Cruz; Karl and Marga Kubler and their daughter Carmen. Before he travels to the island, Karl Kubler takes out Ecuadorian citizenship and visits various authorities. When he arrives on Santa Cruz, he announces that he has been appointed as new comisario (commissioner) and will live in the factory building. The governor is said to have declared that the building as well as the houses of Stampa and Wold as public property!

Wold, who lives at Fortuna when he is not aboard Santa Inez, loses his house to an Ecuadorian soldier in the company of Kubler. The Stampa family continues to resist expulsion from their house, but Worm-Müller is thrown out of the factory and sees no alternative but to move into the old chicken house behind the factory. At the same time they lose access to the factory's cistern with its accumulated rainwater.

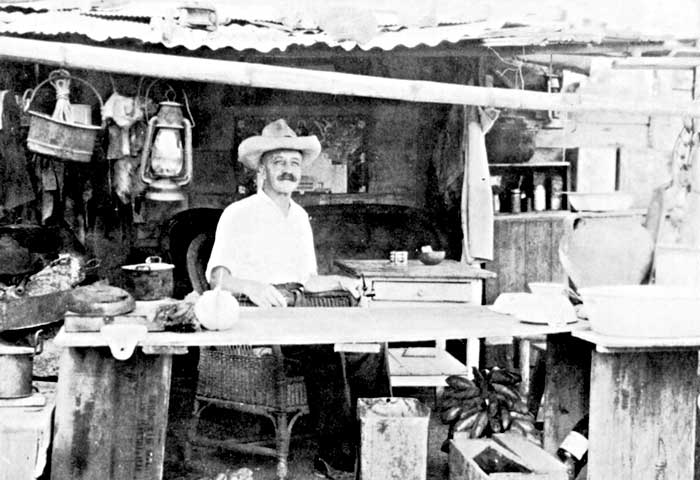

Arthur Worm-Müller had to get out of the factory when Karl Kubler§ arrived with his family in 1934. But gradually he thrived in his refurbished chicken house. He had no children but is remembered by the youngsters of the 1930's as a pleasant uncle-figure. Photo courtesy of Jacob Worm-Müller, Oslo.

§ In her unpublished What Happened On Galápagos?, Margret Wittmer states that Kubler lived on Isabela for a while, then sent for his wife and daughter to join him. Apparently he moved to Santa Cruz after they arrived from Spain. In Leon Mandel—Field Museum Galapagos Expedtion, Mandel's wife Carola describes Kubler and his house.

After much work, the Worm-Müllers have it quite cosy in their restored chicken house, but soon Hilda considers it too primitive and returns to Guayaquil.

Another status report from Worm-Müller, dated December 1, 1934:

“We have had quite a few changes here. The German who arrived here and had me put out of the factory building became so unreasonable that we got the governor to dismiss him as “comisario.” Now he has toned down a good deal but still tries give us Norwegians and the Dane as much trouble as possible. He was overheard agitating the natives to kill us, so we sent for Stampa and Wold who were up in the hills harvesting their coffee. The plan was to “take” each of us, one at a time, and the fellows up in the hills were to be “taken” first. Naturally, we said nothing but walked around with our firearms plainly visible.

“When one man had to attend his boat, for example, another stood on the landing pier with a rifle. These were not the nicest days I have had on the island. Imagine nights with a gun at the bedside! Now all that is passed and everything continues as before.”

The next mishap to befall the colony comes when Santa Inez runs aground near Esmeraldas, on the north coast of Ecuador. During the two years that the boat was used for fishing and freighting it caused many problems for the Norwegians because of engine failure, incessant repairs and endless expenses. Finally, Wold is exasperated and after the last disaster declares that the ship is bewitched. But nobody perishes and Wold considers himself lucky to have had a another narrow escape. He decides in earnest to concentrate only on his coffee plants. Besides he recently got a nice neighbor. Jens Moe, who originally was aboard “Ulva,” has returned from Colombia and settled in the hills arriba between Wold and Horneman, where he is busy establishing a chicken and pineapple farm.

Herman and Helga Lundh give up for the time being after the fiasco with Santa Inez. They move to Guayaquil.

The Stampa family becomes a friend of William A. Robinson, an American sailor who is visiting the Galápagos in 1934. A few years earlier he sailed around the world in his 32 ft. ketch Svaap. After that accomplishment and the book he subsequently wrote, he has became world famous. Now he is back again at one of his favorite places to produce a nature film. Moreover, he is fascinated by the Norwegian colonists and wants to write a book about them.

Stampa helps with the preparations for filming, and Worm-Müller provides information about the Norwegian expeditions.

Robinson has a base camp in Tagus Cove on Isabela and is getting on well with his filming when he develops a ruptured appendix and peritonitis (abdominal inflamation). A coincidental visit of a ship with a wireless radio aboard saves him. His condition is reported to the Canal Zone where a military sea plane departs for Tagus Cove and flies him to the mainland. [This was history's first airplane service to the Galápagos.] While in the hospital in Balboa, thieves vandalize his yacht and strip it of everything of value. Only the engine is recovered by an American fishing boat, which reports the damages by radio.

Robinson cannot bear returning to his beloved boat in the Galápagos and decides instead to give the hull to Stampa and Worm-Müller in appreciation of all their assistance.

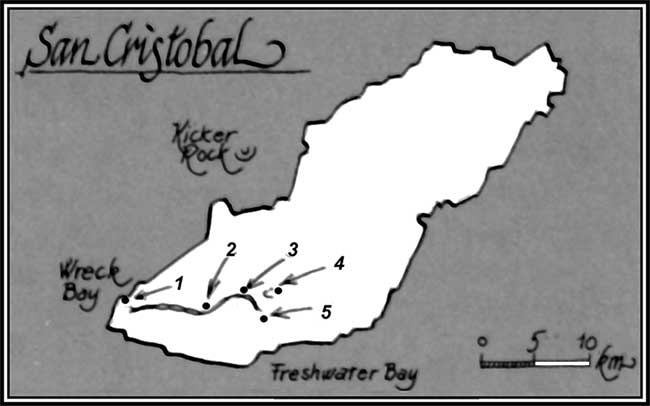

Just after New Year, 1935, Stampa sails Falcon the long way around to Tagus Cove and tows the hull of Svaap back to Academy Bay. The newly installed governor, Colonel Carlos Puenta at San Cristóbal, does not appear any friendlier to the Norwegians than his predecessor. He does not accept the explanation that the hull is a personal gift, since there are no documents to this effect, only a radio communication to Stampa through the fishing boat. Promptly the governor confiscates the yacht and tows it on to Wreck Bay. Robinson has arrived at Tahiti before he receives news of what has happened. While the dispute over ownership continues by telegraph and letter, Svaap is one night driven ashore in Wreck Bay and damaged. It is now February 1936!

A group of scientists from the University of Quito visiting in 1938, here photographed in front of the Stampa family's first house. Standing, second from left is Karl Kubler, then Helga Lundh and in front of her, Anne Stampa who holds the hand of her mother, Alvhild. Next to her is Solveig Graffer. Photo courtesy of Jacob Lundh, Oslo.

Reluctantly, the authorities finally agree that the wreck does belong to the Norwegians. Stampa and Worm-Müller sell it for 30 dollars.

Svaap is sanskrit for dream. Does this spell the end of a dream of that new and modern motorsailer for the Stampa family? Oh no! Puffing his pipe, Stampa studies Falcon from all angles. Is it possible to rebuild an open Norwegian motorboat into a proper auxiliary yacht? [Meaning a sailboat with engine.]

In the Fall of 1936, Falcon is pulled ashore. The boat is 24 ft. long, has one mast and is only half decked. Stampa has his past experience in cutting constructions down the middle, and that is what he does with the boat. He separates the halves by a space of two meters (6.5 ft.), adds boards and beams, a deeper keel, lays a complete deck, splices the wires, sews the sails, erects one more mast. After some months he launches a white-painted 30 ft. ketch—an ocean-going yacht almost in the same class as Svaap.

Towards the end of the thirties, new colonists continue to arrive in Santa Cruz. One more Ulva-man returns in 1935; it is Anders Rambech. The next year his fiancé arrives, Solveig Hansen from Oslo. The Kastdalen and Graffer families from Rjukan also arrive in 1935 with a huge cargo. Later, the Lundberg family from Sweden and several German and Ecuadorian families follow.

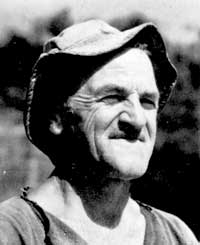

Anders Rambech was the last of the four original Ulva members who decided that Santa Cruz really was a paradise. He returned in 1935. Photo courtesy of Per Høst, 1953.

In 1938, Herman and Helga Lundh are back after four years on the continent. They have Jacob with them—who is now 10 years old—and the four year old Eric. In the same year, Jacob Horneman is in Europe and returns with a new wife, Elfriede Engelmann from Frankfurt, Germany. Anna had her fill of Galápagos and in 1933 finally moved to Lillesand with Robert. By the late thirties, others also leave the island. In 1937, Arthur Wurm-Müller becomes ill and moves back to Guayaquil to join his wife Hilda. She has made brief visits to Norway and the U.S.A. where she has studied hairdresssing and cosmetology and has opened a parlor that is ultimately successful. Ræder understands that there is little money to be earned in the Galápagos and he, together with his wife, also leaves. María Nuggerud sells her small property to Kubler and moves with little Oscar Trygve to the continent. She does not speak Norwegian and most Norwegians among the Europeans do not speak Spanish. There is also a definite class distinction which prevents communication and association. A “Señorita” from an ordinary Ecuadorian working class family might be acceptable as a mistress but as yet not as a wife.

The Canning Factory Burns

In 1938 there are so many people on Santa Cruz that an army garrison is established on the island. For this the factory and the two oldest houses are needed. Now it is Kubler's turn to move out. The Stampa family has to be content with one of the cabins used by Ræder's workmen.

Three Ecuadorian soldiers at Wreck Bay in 1933. Photo courtesy of John S. Garth, Los Angeles.

The chief of the garrison is Lieutenant Gonzalo V. Bedoya. On his staff are a half dozen soldiers and a few servants. One evening, while the men are playing cards upstairs in the factory, a servant adds more kerosene to one of the lamps without first extinguishing the flame. The container is filled to overflowing with the kerosene dripping over the floor. The very dry Norwegian wood catches fire immediately and within seconds the flames are licking up the walls. Everyone escapes unhurt except for the boy who started the fire; he receives some minor burns. But the entire building is soon ablaze; and the army's store of ammunition and dynamite is also ignited. And so the twelve year old factory is totally consumed by fire to the accompaniment of a barrage of shots and heavy explosions. None of the other houses catch fire. In retrospect, one can say that the factory went down with a final salute that was a fitting tribute to the Norwegian pioneers!

Next morning there is a knocking on the door of the Ræder house where the Lundh family is staying. Ten-year old Jacob will never forget the sight that meets him when he opens the door. There Lieutenant Bedoya is standing, dressed only in his underwear but wearing his officer's cap, and very embarassingly asking for help with food and clothing for himself and his men.

The poor soldiers got help from Lundh, Stampa and the others, and following this there comes a change for the better in the relationship between the authorities and the “foreign natives.” So although it was sad to lose the fine building, it brought about something good.

When the Stampa family had to move, they decided to build a house near Bahia Salinas, the Salt Bay. Up to now no one had been building beyond Punta Estrada, the southern headland of Academy Bay. In the past this was where seawater was trapped with small dikes during spring tide. When the water evaporated the salt could be harvested. The small inlet provided a good harbor for Falcon, and it was also a beautiful bay, bordered by dense green mangroves silhouetted against white coral sand and black lava headlands, with azure surf beyond.

There was a perpetual lack of cash and raw materials, but Stampa knew, after working on Falcon, that the local heavy hardwood, matazarno [Erythrina velutina] was an excellent material. With the help of tools from Kastdalen and Graffer, he felled trees arriba and sawed them into rafters and boards. Slowly but surely there arose a beautiful house with concrete cisterns, balcony and a stone wall along the beach. It was an isolated site, so they needed a rowboat to get from Punta Estrada to the other side of Academy Bay. But the rewards were peace and quiet and the most beautiful view of the playa.

The house was named “Arena Blanca,” White Sand.

Between World Wars I and II, income was sparse. Tons of bacalao were harvested, salted and dried—and often wasted. The company in charge of “San Cristóbal,” which set the freight rates, was rarely willing to cooperate with the Norwegian fishermen. This was understandable as the company had their own fishermen at Wreck Bay. The situation reflected Ecuador's poor economy, with everyone struggling to make a living. The United States was interested in purchasing the archipelago by virtue of its strategic position with respect to the Panama Canal. This is one of the reasons why President Roosevelt personally visited the islands in 1938. But strangely enough, none of Ecuador's ever changing governments showed any interest in this proposition. In 1934 the islands were already declared a National Park—a most commendable action by a near penniless nation!

Had it not been for foreign ships which often called, and American adventurers and scientists leaving behind both currency and equipment, the colony on Santa Cruz could hardly have survived. The Europeans had great problems accepting the living standards of poor Ecuadorian workers. So far they had neither school nor doctor on the island and a lot of compromises had to made.

Jens Moe, 1926. Photo courtesy of Gudron Moe, Kragerø.

Jens Moe was the first to acquire a radio, and it was he who first heard that Germany had invaded Norway in 1940, scarcely without resistance. Alvhild Stampa remembers how all the Norwegians gathered in Kastdalen's house afterwards. The house was called “Miramar” (“Ocean View”) and was located near Horneman's. They had a hand-cranked gramophone, and when somebody played the nostalgic hit,“Beneath the Old Lilac,” there were several who wept.

They did not yet know that the war, paradoxically, would become a goldmine for the colony. In 1941 the United States signed a leasing agreement with Ecuador and established a large military base on the island of Baltra, situated directly north of Santa Cruz. Within record time, the population of Galápagos increased spectacularly, and now they had an airstrip, a radio station, shops, physicians and hospital. And customers!

With World War II and the American base at Baltra, prosperity comes to Galápagos. Soldiers picked up provisions at the Ulva pier or they were delivered by motorboats to Baltra. Photo courtest of the Kastdalen family, Santa Cruz.

To help supply the seven thousand servicemen stationed on Baltra, the Americans purchased all that could be fished, caught and produced. And at a good price. They arrived in boats according to a schedule, or one could deliver a catch of fresh fish oneself. Not uncommonly, the orders arrived by airmail, literally.

Kristian Stampa received from the Americans detailed ocean maps of the region, which enabled him to explore reefs and shallows that prove to be fine fishing grounds previously unknown to him. The fishing became better than ever and the income sky high. Alvhild could afford a trip to Guayaquil bringing back leather-upholstered furniture and other “luxury items.” And, not the least important, they could afford to bring more children into the world. In 1942 Marit arrived, and in 1945, Knut. Both were born on Arena Blanca and both were cradled in the same tortoise shell their father had made when Anne was born.

In 1947, the United States paid the last of her leasing loan to Ecuador, donated the wooden barracks to Galápagos residents and bulldozed the remains of the base into the ocean. Ecuador took over the airfield and soon started regular air traffic to Guayaquil. Modern civilization was about to embrace Galápagos.

By 1948, it was time for the Stampa family to have a well-earned vacation. Kristian had not been home in Norway for 22 years, and for Alvhild it was 15 years. Their good financial status allowed them to take along all three children. They planned to have Anne stay with her aunt in Stokke near Sandefjord and attend Rørkoll school.

The rest of the family would return with a new Norwegian Galápagos expedition…

Just as a cobbler's children are often without shoes, so the house of carpenter and master builder Sigurd Graffer was not a luxury dwelling. In 1958 his family had left him and he lived mostly down at the beach. The house in the highlands was overgrown, and the timber rotting. Photo Courtesy of Erling Brunborg, Oslo.

Inset: Many an enjoyable mug of coffee was served between the supporting poles of Wold's house. Here are Gordon Wold and Sigurd Graffer, about 1965. Photo courtesy of Sven Gillsäter, Sweden.

The Thalassa Tragedy

The Stampa family traveled from Guayaquil aboard Sophie Bakke of Haugesund and were home in Norway on Midsummer Day, 1948. [St. John's Day, June 23rd.] Anne 14, Marit 5, and Knut 3 years old suddenly became acquainted with numerous grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins. All wanted to please the travelers from the exotic islands in the Pacific, show them the home country and entertain them.

The children, especially Anne, got tired of all the fuss in the beginning. She wished she were far away when journalists arrived, took photographs, and asked all sorts of silly questions.

For Alvhild and Kristian the visit was important for another reason besides meeting the family again. It was a small triumph, a demonstration of success. Previously, it was concluded in Norway that Galápagos expeditions were financial fiascos and that life on the islands mainly consists of dangerous toil with small gain. And here were Kristian and his family, returning with a bulging purse and a photo album filled with evidence of an exciting life among cacti and tortoises, iguanas, a baroness, presidents and millionaires! Apart from the fact that Alvhild and Kristian Stampa were two humble persons, they surely seemed like real Norwegian Americans… [ A lot of Norwegians have emigrated to North America, forever returning on vacation, displaying wealth and importance.]

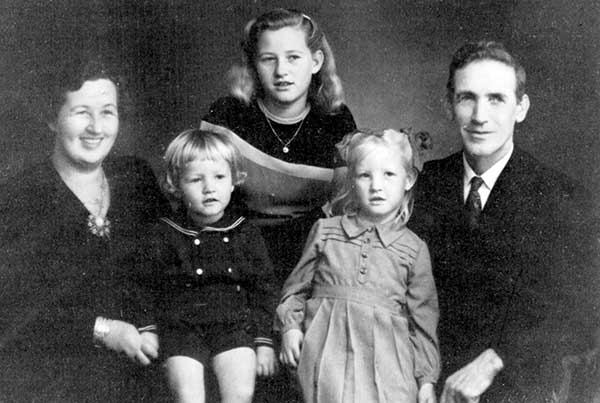

During their visit to Vestfold in the summer of 1948, there was time for a trip to photographer Jørgensen in Sandefjord. From left to right: Alvhild, Knut, Anne, Marit and Kristian Stampa.

A good part of the profits from Galápagos would be reserved for a new Galápagos expedition. The dream of a Norwegian canning factory was to be realized through the united company “Stillehavs-Fangst” (“Pacific-Catch”). Prime movers of the project were Arne Chr. Karlsen and Lars Karterud.

Karterud is the same one who participated in the Ulva expedition in 1926, and according to the ship's newspaper,“Gapa-Lagos,” should have his name changed to Kasterud [Kaste in Norwegian means to throw or cast, as in harpooning.] because he so skillfully harpooned a dolphin! After Galápagos he roamed around the world for a while, fished lobster in South Africa, and fought for Finland during the Winter War of 1939. In recent years he worked as a fish merchant in Stavanger.

Arne Karlsen originally came from the fishing hamlet Kiby, near Vadsø. Together with his wife, Svanhild, who came from Kirkenes, he for several years ran the Lille Langerud farm in Abildsø on the outskirts of Oslo. After the war the farm was sold as a housing site for the city, and with the profits they bought a house in Asker (also near Oslo) and a lumber yard in Stavanger on the west coast. Now everything was sold and 100.000 kroner invested in “Pacific-Catch.” Consequently, Karlsen was the financial backbone of the enterprise. During the voyage he would serve as first mate.

The other members of the expedition invested in shares amounting to 5000 kroner and more. In addition to those participating in the journey across, Gordon Wold and several others on Santa Cruz had paid for shares and also ordered equipment they needed from Norway.

Aboard Thalassa in Stavanger, Autumn 1948. From left to right: two unidentified men, Lars Karterud, Arne Chr. Karlsen. In foreground; Erling Karlsen (9 years old), Arnhild Karlsen (10 years old). Photo courtesy of Arnhild Karlsen Utheim, Oslo.

With the experience of Karterud and Stampa from the Ulva Expedition, it should be possible to avoid most of the mistakes of 22 years ago. The formal petitions for fishing concessions were arranged by the consul general in Quito, who was still Haakon Bryhn, and the Ecuadorian chargé d'affaires, Jorgé Perez Concha, and consul Henry Wilhelmsen in Oslo.

New Galápagos Expedition being planned.

A New Attempt to start Norwegian Canning Factory.

A pair of Norwegians, merchant L. Karterud, Stavanger, and Arne Karlsen, Oslo, are planning an expedition to Galápagos. They intend to build a canning factory on the islands and hope to transport all the necessary machinery.

They are now working on the purchase of a suitable vessel for the expedition, and the plan is to leave in August. They are concentrating on a 120-ton yacht.

Karterud took part in the 1926 Galápagos expedition. It failed mainly through the lack of skilled personel, and of the original 45-man crew, only four are still there. One of these is Edvardsen Stampa from Sandar. Now he is back in Norway as a wealthy man.

The intention is that expedition members themselves shall do all the fishing and processing of goods. The total cost of the expedition is estimated at a quarter-million kroners. No less than 650 interested persons have stated their wish to participate, but only 20 can do so.

The expedition's ship, Thalassa, was a former American pleasure craft of 100 tons gross, built in 1933. During World War II she was used as a military surveyance craft. On the quarterdeck stood a short mast where one could set a small supporting sail, but otherwise she was a genuine motor-cruiser. Twin engines gave a maximum speed of 16 knots.

The captain on board was Carsten Willumsen from Stavanger who, at 55 years of age, was the expedition's oldest member. Previously he had piloted several ships and was known as an able seaman. In addition to Willumsen, Lars Karterud, the Stampa family (with the exception of Anne who would go to school in Norway) and the Karlsen family (parents Arne and Svanhild, with children Skjalg, 14 years old, Arnhild 10, and Erling, 9 years old), the expedition had the following members:

- Ansgar Breivig, first engineer from Oslo,

- Johan Stene, second engineer from Trondheim,

- Hans Hansen, cook from Klosterskogen near Skien,

- Torstein Kvarekval, electrician from Dale in Bruvik,

- Daniel Liadal, store manager from Øystese,

- Bernhard Jacobsen, sailor from Tromsø,

- Hedvig Søberg Olsen, expedition secretary from Oslo.

On Santa Cruz the secretary Miss Olsen will be the teacher of all Norwegian children on the island.

Preparations for the expedition had been going on for some time before the Stampa family returned to Norway. The original plan was for Thalassa to leave from Stavanger in September-October, arriving at Santa Cruz for Christmas.

However, collecting supplies and the many other preparations took more time than was estimated. There were also delays due to the customs authorities demanding duty on the purchase of the U. S. registered ship. Payment was avoided by arranging that the formal purchase of the vessel only would take place upon arrival in Panamá.

Another, more well-meaning authority that caused delays, was the Coast Guard. It claimed that the engines were in poor condition and had to be overhauled at a mechanical work-shop, or, preferably, replaced, before Thalassa would be declared “seaworthy.” Arne Karlsen pointed out yet again that the ship was American, and therefore the Norwegian authorities could not restrain her. Besides, engineers Breivig and Stene were confident that they could get the engines into first class condition themselves.

Only on November 28th was Thalassa was seen motoring out of Stavanger.

But the expedition was plagued with bad luck from the start. After only a few hours at sea the main bilge pump failed, and the same evening found the ship at anchor back in Stavanger. Nevertheless, the Stavanger Aftenblad newspaper announced that:

“Galápagos Travellers Keep up the Spirit

The fog in Dusaviga (off Stavanger) will be forgotten when they sit beneath the palms

Those who thought that the people aboard Thalassa would be discouraged because a malfunctioning bilge pump delayed their departure were absolutely mistaken. From the three year old Knut Stampa, with his fair curls, and dressed in a blue overcoat, to the oldest, it is good spirit that impresses a visitor to the ship.

—Naturally, we expected to get to warmer territory as soon as possible, but sulking is of no use.

—But of course it is annoying, says Miss Søberg, who is tidying up Captain Willumsen's cabin while he, Karlsen and Karterud are ashore with the damaged part of the pump.

Down in the engine room the engineers, Stene and Kvarekval, are working hard and, judging from the color of their hands, face and clothing, they are doing a thorough job.

Thalassa was 20 nautical miles off the coast when the problem with the bilge pump developed. One could have continued since there were spare bilge pumps on board, but they did not want to tackle the North Sea without everything in working order. This was a decision by the ship's counsel.

Now that all equipment is aboard, it is somewhat cramped. On the stern and amidships, barrels of fuel are securely fastened, and on the port side, a lifeboat is lashed to the deck.

Maybe it was fortunate that everything was so well tied down, we ask Stampa and his wife, who are having a break on deck.

—Yes, it was. We had some of the seas from directly ahead.

Knut and Marit, 3 and 6 years old, romp around with Erling and Arnhild Karlsen. Erling announces that he is 9 years old, but when he hears Arnhild reporting that she is 10½, he immediately adds half a year to his age and says that that he really is 9½.

Stored below deck are provisions of all kinds, occupying a lot of space.

—This will improve once we are underway and get everything properly stored. And then it may be good to have something to do.

Knut and Marit, each with a broom, attempt to sweep the deck.

—During the voyage, won't it be somewhat of a problem to keep the little ones safely aboard, without risk of their falling into the sea?

—Oh, they will quiet down after a few days, all will go well.

—Inside the cabin it is rather cramped but nevertheless cosy.

—There will be more space once we have rearranged things, says Mrs. Karlsen. There is always some disorder at the start but just wait. And we do expect warmer weather pretty soon, and then we will not spend much time in the cabins. We hope to be able to stay on deck most of the time.

Skjalg, who is our ‘ferry man’ is an adolescent who adults consider to be a child, although he considers himself to be an experienced hand. He comes from Kirkenes.

—Just stay back here and freeze, he says when he rows us ashore. I shall certainly enjoy the southern sun and summer.

As I mentioned before, Thalassa can make 16 knots with both engines running, but during the trip will cruise at 10-12 knots. But should there be a need, it is good to have some reserve—the voyage is long. And now all aboard are yearning to get around the Tungeneset [the headland on the NE tip of the peninsula where Stavanger is situated.]

—Next time there will be no return, you will see, Skjalg says as a farewell greeting.—You can rest assured…!

This one repair revealed the need for others, and so Thalassa's departure kept being delayed. The Stampa family then decided that Alvhild and the two children should travel across the Atlantic in a larger ship and wait for Thalassa in the West Indies.

There were several reasons for this. First of all, 6 year old Marit was very seasick during the short trial cruise; secondly, the danger of foul weather was increasing all the time because of the delays, and thirdly, there were several warnings from people who considered Thalassa unseaworthy. The ship had not been certified since her construction 15 years earlier, and according to statements from the Coast Guard, no insurance company was willing to insure the ship, the cargo or the passengers.

Kristian and Alvhild decided that it was wisest to separate the family, and Alvhild, Marit and Knut instead left Sandefjord aboard the whale factory ship Kosmos V.

On December 17th, Thalassa finally leaves Stavanger. On December 22nd they have passed through the most feared stretches. The North Sea, the English Channel, the Bay of Biscay and Cape Finisterre are behind them and they are safe in the harbor of Vigo in Spain. But there have been some difficult times with nothing but bad weather and much seasickness.

While there is still daylight, Christmas Eve is celebrated on deck with a Christmas tree, songs and exchange of gifts. The Spaniards along the pier observe them with amusement. Ten year old Arnhild's best memory of the occasion is a crate filled with oranges—ripe oranges. In Norway oranges are a still rationed luxury. Here she can eat as many as she wishes!

The cook, Hans Hansen, uses the stay in Vigo to write a letter to a friend in Stavanger:

“Around Cherbourg we had heavy pitching seas, and Thalassa sure did show her worth. At the Channel Islands we had the most exciting adventure to date. Because of the high waves we proceeded with only one engine. When we were near the narrow strait between the Channel Islands, it suddenly stopped. Luckily, we had the sail up, which helped to steer the ship, but nonetheless we drifted quickly towards the breakers. We discovered that water had got into the fuel, and we drained off water by the bucketful before the fuel returned. The entire event did not last more than 10-15 minutes—but we sure do not wish for a repeat of those minutes…

“…it has been an adventurous voyage, but I will advise no one to do likewise. The sea is too big for a 100-ton ship. When I stood on the quarterdeck, which is only a few feet above the surface of the sea, I realized how small the ship really is. But Thalassa managed marvellously. She wagged her tail a little and climbed up, no problem How well she copes you can understand from the fact that we did not have a single sea of any size across the deck. When we arrived at Vigo, we had not lost a single board from the deck's cargo.”

This letter is the last known message from the Thalassa expedition. From fourteen of the fifteen people aboard, there will never be more messages whatsoever.

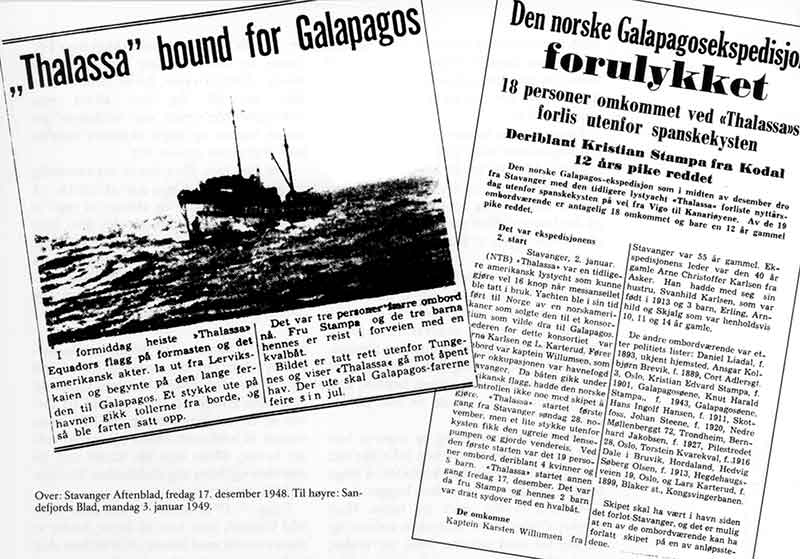

| Stavanger Aftenblad, Friday December 17, 1948:“Thalassa” bound for Galapagos | Sandefjords Blad, Monday January 3, 1949: The Norwegian Galapagos Expedition Wrecked |

|---|---|

| 18 persons died in “Thalassa” disaster off the Spanish Coast Among these was Kristian Stampa from Kodal 12 year old girl rescued | |

| This morning “Thalassa” hoisted the Ecuadorian flag on the foremast and the American astern and left the Lervik quay to start the long trip to Galapagos. A distance away from the harbor the customes officials left the ship and the speed was increased. There are now three persons less aboard. Mrs. Stampa and her three children have gone ahead aboard a whaling ship. This picture is taken outside Tungeneset and shows “Thalassa” heading for open sea. That is where the Galapagos travellers will celebrate their Christmas. |

The Norwegian Galapagos expedition which left Stavanger in the middle of December aboard the former pleasure yacht “Thalassa” was wrecked New Year's Day near the Spanish coast en route from Vigo to the Canaries. Of the 19 persons aboard, 18 are thought to be lost and only a 12-year old girl was rescued. This was the second start of the expedition. Stavanger, 2 January (Norwegian Telegraph Bureau) “Thalassa” was a former American pleasure craft capable of doing 16 knots with the mizzan sail hoisted. The yacht was originally sailed to Norway by a Norwegian-American who sold it to the company planning to sail to Galapagos. The leaders of this company were Arne Karlsen and L. Karterud. The skipper aboard was Captain Willumsen who during the [German] occupation was Harbor Master in Stavanger. Since the ship sailed under the American flag, the Norwegian Coast Guard had nothing to do with the vessel. “Thalassa” started originally from Stavanger on Sunday, November 28, but after a short trip along the coast, the bilge pump failed and they returned. During the first start there were 19 persons aboard, including 4 women and 5 children. “Thalassa” started for a second time on Friday, December 17. At that point Mrs. Stampa and her 2 children had left to go south aboard a whaling ship. [List of those who perished is not included here. See names, above.] The ship is supposed to have visited harbors since leaving Stavanger and it is possible that one of the participants may have left the vessel during one of these stops. |

On New Year's eve, Thalassa begins the voyage from Vigo to the Canary Islands. The weather is bad and it soon becomes worse. It quickly gets very dark as a full blown gale is raging. Between one and two o'clock at night some fishermen in the village of Bayona are alarmed to see the lanterns of a small ship heading out to sea in the awful weather. Unable to do anything to help, they witness how the ship is pushed off course in the narrow shipping lane and thrown against the El Lodo rocks.

The lanterns immediately go out and Thalassa breaks in two. The fore part disappears into the depths within seconds, the stern section remains on the reef for a few minutes before it is also washed off and sinks.

Arnhild Karlsen is staying in the stern cabin together with her mother and two brothers. They try to sleep, but even below the movements are violent and several times she nearly rolls out of her bunk. She lies listening to objects sliding back and forth on the floorboards in synchrony with the ship's pitching and rolling.

Suddenly there is an enormous crash and the ship heels over more than ever before. There is a mixture of creaking and thumping noises as Arnhild is thrown against one of the sides of the cabin. She hears the sound of water pouring in and her brothers screaming. Then her father rushes down the steps and shouts for them. Even before he says so, she understands that they have hit a reef. They must all get up on deck immediately.

Her father helps her up the steps, her mother follows with Erling. Skjalg manages on his own. Even before they start to climb, they wade in water, and from the open door water gushes over them. On the sloping deck she sees that only the stern section of the ship remains—the front half has disappeared.

Her father fetches life-jackets from a chest on deck. All the time the seas wash over them. Arnhild is naked; the wind blows wet and cold. She is scared and shivering but does not cry. She gets a glimpse of Kristian Stampa, clinging to something a few feet away. Her father struggles with the straps of the life-jacket. Her mother is trying to put a vest on Erling.

Finally, her father has finished securing the life-jacket and shouts that he will tie her down so that the waves cannot wash her away. But before he can do this, a huge sea buries them completely.

Arnhild is torn away from her father. She feels herself rolling against rocks and protects herself with outstretched arms. She goes under; the sea is boiling and roaring everywhere. She needs air. Finally she gets her head above water and can again breathe. She thinks how strange it is that the water feels warm and welcome. Up on the ship it was a so cold and evil…

Arnhild does not know how long she remains in the water, but it is still night when she is washed up on a beach and manages to crawl far enough to be out of reach of the foaming waves. There she falls asleep, battered and exhausted.

When she awakes it is light. A short distance away is a small stone house. Her entire body aches as she walks slowly toward the house. There she meets two soldiers. They are startled to see her and say a lot that she does not understand. She is embarrassed to be dressed in nothing but a life-jacket, but when the soldiers hand her a pencil and paper, she understands that she should write her name.

This she does but it is difficult and hurts because she has abrasions and cuts on arms and hands, and the paper is stained with blood and sand. Now she is quickly wrapped up in a blanket and carried to Captain José María Nieto. He is chief of the Bayona Coast Guard. [Bayona is a small fishing and tourist village west of Vigo, Spain.] His wife takes care of Arnhild's injuries and gives her a bath, food and new clothing.

On Monday January 3, 1949, Norwegian newspapers carried news of the tragic shipwreck on their front pages. According to Verdens Gang and the Stavanger Aftenblad, Arnhild should have said that one of the crew of Thalassa swam ashore with her and therefore saved her life. While she was thrown up on the beach and reached safety, he was apparently washed away.

In 1992, 44 years later, Arnhild Utheim, as she is now known, cannot remember that anybody swam with her or that she should have said something to this effect. But she remembers that three bodies were found on the beach and she had to identify them.

The three were Arnhild's mother, Svanhild Karlsen, Miss Hedvig Sødal Olsen and Ansgar Breivig. Later, Erling Karlsen and Kristian Stampa were also found. All were buried in Bayona.

In addition to the loss of 14 persons, Thalassa took with her into the depths fishing gear and fish canning equipment valued at more than 250,000 kroner. The ship itself and other equipment were worth 400,000 kroner—a considerable fortune in 1948.

Nothing was insured.

From the Monday, January 3, 1949 edition of Vestfold: The boat pictured below is the Stampa family's Falcon; originally a 24-foot motorboat which was shipped about Ulva. Stampa completely rebuilt the boat in such a manner that it became a seaworthy 30-foot motor-sailer.

14 Norwegian emigrants perished in Shipwreck off the Spanish Coast.

Members of the Galapagos expedition drowned in the loss of “Thalassa.”

Little Arnhild is the only survivor.—

Kristian Stampa and his five-year-old son among the perished.

(N. T. B.) The Foreign Service Department tonight confirmed that the luxury yacht “Thalassa” has been shipwrecked on the Spanish coast. According to the report received by the Foreign Service Department there were 15 people aboard, of which only one is saved, the 11-year-old girl Arnhild Karlsen.

N. T. B. was informed by Police Headquarters that when “Thalassa” left Stavanger, December 17th, there were 16 people aboard.

The captain was Karsten Willumsen from Stavanger, and the expedition leader was the 40-year old Arne Christoffer Karlsen from Asker. He had with him his wife Svanhild Karlsen and three children; Erling, Arnhild and Skjalg. The others aboard were Daniel Liadal; Ansgar Kolbjørn Brevik from Oslo; Kristian Edvard Stampe, Knut Harald Stampa, Hans Ingolf Hansen from Skottfoss; Johan Steen from Trondheim; Bernard Jacobsen from Oslo; Torstein Kvarekval from Dale in Bruvik; Hedvig Søberg Olsen from Oslo, and Lars Karterud from Blaker.

Mrs. Stampa changed ship.

“Thalassa” was brought to Norway by a Norwegian-American and sold to the company which wanted to emigrate to the Galapagos.

Leaders of this consortium were Arne Karlsen and L. Karterud. The yacht first started from Stavanger on Sunday, November 28, but trouble developed with the bilge pump and was forced to return. There were 19 persons aboard, of which four were women and five where children. The second start of the expedition occurred on Friday, December 17. Three people had left ship, namely, Mrs. Kristian Stampa and her two children, who obtained passage on a whaling ship.

“Thalassa” is supposed to have entered harbors after she left Stavanger, and it is possible that one of the passengers left the ship at a port of call.

It is with great sorrow that the news of the passing away of Kristian Stampa and his 5-year old son is received in the district of Sandefjord. Kristian Stampa moved to the Galapagos many years ago, and with hard work he succeeded in building his home and providing a sure income in the islands. This summer he came home with his family to visit friends and relatives.

The other members of Kristian Stampa's family travelled to Galapagos aboard a whaling ship, and are left to endure the great loss of the focal point of the family.

A wave of sympathy will flow to them and all the others who lost their loved ones.

With optimism and faith they left, hoping to build themeselves a future, and instead it ended this way so suddenly—We pray that they may rest in peace.

[Caption under ship photo] Kristian Edvard Stampa and wife aboard Stampa's fishing boat.

On January 3, 1949, the Foreign Ministry sent the following telegram to the Norwegian consul in Willemstad, Curaçao, West Indies:

“PLEASE CONVEY TO MRS STAMPA JUST ARRIVED WILLEMSTAD KOSMOSFIVE THAT HER HUSBAND PERISHED IN MOTORYACHT THALASSA SHIPWRECK OFF SPAIN DECEMBER 31ST STOP FAMILY SENDS SINCEREST CONDOLENCES AND DESIRES INFORMATION IMMEDIATE PLANS STOP PLEASE GIVE HER AND CHILDREN NECESSARY ASSISTANCE:

FOREIGN MINISTRY”

Alvhild Stampa could not bear to continue to Galápagos but returned to Norway. After the loss of Kristian, by 1985, when this was first written, none of the Stampa family had been back to the Galápagos (but in later years Knut Stampa has been a regular visitor and his sister Anne has also been back). For several years, Falcon lay lonely and abandoned on the beach of Santa Cruz, waiting in vain for her owner. The house, Arena Blanca—white sand—is still standing (1985) but in sad disrepair.

It may be a poor consolation that although the charts still print the name Bahia Salina, most people today refer to this pretty bay as Stampa Bay. Would it not be an appropriate gesture in honor of the Norwegian pioneers of Galápagos for the official name to become Bahia Estampa?

“Plantation at your disposal”

Jacob Hersleb Horneman's father was a “tall ship” captain from Trondheim. Later he became lighthouse keeper of the northernmost lighthouse in Norway, on the tiny Fruholmen island in Finnmark. [Finnmark is the northernmost and largest of Norway's 20 counties. It borders on the Russian Republic, Finland and Sweden.]

Here, Jacob, an only child, grew up surrounded by untamed, harsh nature, with a minimum of contact with other children, and also little contact with adults other than his parents and a governess.

The boy was very intelligent. As soon as he could read, he became a bookworm, thirsting for knowledge. His reading made him think and reflect and wonder about the many strange aspects of human existence. As he became older, Jacob made a habit of underlining passages in his books, filling covers, blank pages and margins with detailed comments, as if he were communicating with them.

Dreams became an inevitable consequence of the lonely life and all the reading. Jacob had visions of finding gold nuggets in river beds, of silver veins deep in the barren mountains, and of an easier life in a warmer country far away from Fruholmen Lighthouse and Finnmark.

Jacob Horneman never found the silver vein, but at 37 years of age he came to the Galápagos. There he found another kind of riches.

After schooling in Hammerfest, Jacob studied geology at N. T. H. (Norges Tekniske Høgskole). [“N. T. H.” is Norway's Technical University, now part of Trondheim University.] With his interest in the earth's hidden minerals and metals, any other field of study was unthinkable.

After graduation he ended up in the Arctic islands of Svalbard, geologically speaking the country's most virgin territory.[Svalbard is the name more commonly used in maps and gazetteers. Spitzbergen is the name of the main island.] Compared with this Fruholmen was a vacation paradise! For six years he worked at various iron and coal mines mostly as a caretaker. He had plenty of opportunities to roam around and search for the big lode.

The first time that we hear about the Hornemans is in this letter from Sverre Kiserud, the representative of La Colonia de Santa Cruz in Guayaquil, to Thorolf Østmoen who, for the time being, is leader of “Ulvenæs” [“Wolfhill”; the Norwegian name for what later became Puerto Ayora]. The couple got underway from Guayaquil with the flag-decorated “Isabela” on May 17, the Norwegian National Day. After a visit to San Cristóbal, they arrived at Santa Cruz on May 29.

Guayaquil, May 16, 1927

Dear Friend!

It is possible that mining engineer Horneman and wife will arrive at Santa Cruz by first boat. For two reasons, I cannot nor want to enter into a contract with him. The original plan was to go to Floreana, but he changed his mind, and here the “friendship” to Seeberg is a point. For personal reasons I will not do it and also I do not have the authority to write contracts.

Both Mr. Skaraas and I have talked to him and he agrees to the following: For one room and meals, 75 sucres per month per person, and he must not become a burden to the Company. If he wants to settle in the hills, he will have to provide his own house. He and his wife will have to pay for their voyages between the islands, and agree to follow regulations established by the General Assembly or the new leader.

I salute you on the 16th and 17th of May [Norwegian National Days] and wish that all is well at “Ulvenæs.”

Letter courtesy of Kanen Østmoen, Drammen

When the magazine Vi Menn published an article about Horneman in 1963, the editor received a letter from Olav M. Pedersen in Tromsø. He had also worked in Svalbard in the 1920's and he wrote, among other things:

“That Horneman is still alive was a surprise since I thought that he had gone from this world long ago!

“Horneman rowed and tramped around Spitzbergen mostly as a vagabond, both in winter and summer. Many a time he returned to the mines more dead than alive.

“I remember the summer of 1924 when he arrived half dead in Grumann City, wet and frozen. It appeared that he had walked along land-locked coastal ice and at the foot of a mountain had accidentally slipped into the sea. How he managed to get ashore again is still a mystery. There was ice everywhere, even though it was the end of May.

“Horneman was a courageous chap and many legends were told about him by hunters and construction workers on Spitzbergen, Svalbard in the 1920's….”

Author Mikkjel Fønhus was also in Svalbard and met Horneman. He collected stories about this loner, who, regardless of the season, braved the elements looking for valuables in rocks and gravel. In “Men Below the Northern Light” (1948) Fønhus introduces him as Mr. Lederup—caretaker in the English mine “Arctic Coal Co.” Lederup is described as a tall, thin man of few words. Mostly he looked like a savage, but when he spoke he revealed the voice of a cultivated man, one of good background and education. His face was mostly hidden behind a huge beard, with intelligent, slightly restless eyes behind the glasses.

In the Arctic wilderness he walked across the mountains and rowed along the fjords in weather that kept others inside. On one occasion he capsized his boat, lost provisions and rifle, but still did not abort his trip. Instead, he killed birds with stones, and as the saying went at the time, lived on “sea gulls and driftwood.”

When Horneman was determined to complete a project, nothing would change his mind!

And this is also how it was in Santa Cruz. Often it was more his determination rather than skill which drove him toward his goal. As rumors spread in Svalbard that Horneman had ended up on the Galápagos Islands, far away in the Pacific Ocean, it was said that “One day Horneman was out rowing with some other men when the boat suddenly capsized and Horneman disappeared. In spite of a thorough search and dragging for the body, the man was gone. Six months later he emerged in the Galápagos!”

Jacob Horneman was also a romantic who women found very attractive. His first wife was named Anna Gauslaa, a nurse from Lillesand. She was willing to follow him to Svalbard, Santa Cruz—anywhere.

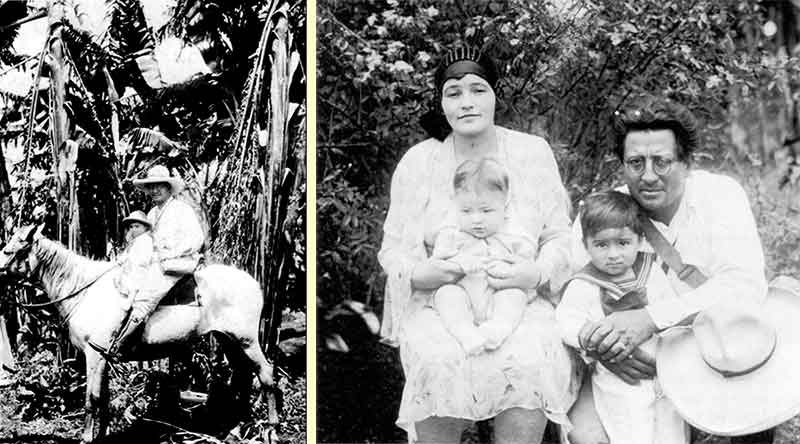

Jacob's interest in Galápagos derived from articles by enthusiastic Ulva participants. He and Anna first arrived in Santa Cruz in May 1927. They settled near Fortuna, where they built a house and lived by farming. But the tragic accident with Birger Rostrup's death, who Anna nursed until he died, and the difficulties when Robert was born, put a heavy strain on Anna. Later the boy developed tetanus and barely survived. When a new baby was expected, at the same time that the island was being depopulated, she wanted to go home to Lillesand. By this time they had been on the island for two years.

As soon as rumors circulated that the colony on Santa Cruz had started up again, Jacob wanted to return. Meanwhile, Christian, who was born in Lillesand, remained with his grandparents, while the other three, Jacob, Anna and Robert, spent a new two year period on Santa Cruz. But in 1933, Anna Horneman wanted to go home for good. By now she had enough of Galápagos. Jacob was equally determined to stay, so they ended in divorce.

After an interim as a miner in South America and Africa, Jacob returned to Santa Cruz with a new wife—a dancer, 20 years younger than himself. Else Jørgensen came, had a brief look, and left again. Galápagos was not her notion of paradise. She demanded a divorce and opened a hairdressing salon in Guayaquil instead.

Geology engineer Jacob Hersleb Horneman from Finnmark was, for more than 40 years at Santa Cruz, a personality among personalities. And here he is with his faithful donkey “Mikkel.” Photo courtesy of Erling Brunborg, 1958.

A new mining sojourn brought Jacob Horneman to England in 1938. There, a friend of his, Florence, told him that she knew a woman in Frankfurt who would be suitable for him: a secretary skilled in languages and with an adventurous spirit. Her name was Elfriede Engelmann.

Jacob sat down and wrote to this woman who he has never met:

“I beg to offer you a guaranteed position as colonist in the Norwegian company on Santa Cruz Island, and place at your disposal a small plantation and a small house. Your eventual neighbors, men, women and children, are all Scandinavians, but some of them speak English. They are the best people on the entire island!

“In fact, here we find only nice people, there are no dangerous animals, no malaria or contagious diseases. You will feel much safer there than I do in London—neither airplanes nor submarines can trouble you.

“The climate is as healthy as anyone could wish for, and life on the island gives both energy and strength. The equatorial line crosses the islands, but the cold current from the South Pole makes the climate comfortably mild, like an ordinary summer in England. Every morning you will awaken fresh and fit and full of energy for a new day, which you may spend in the garden, or on horseback, riding to the beautiful sandy beach for a fishing trip.

“In the mountains one has a magnificent view and finds many strange rock formations that awaken the fantasy. Bringing a tent, one can experience unforgettable hours around a small bonfire with a mug of coffee. Such excursions you can take as often as you wish, and you will enjoy life more than most people in the world.

“I mentioned the plantation. It is not big but there are lots of fruits and vegetables at your disposal. Also, we have plenty of poultry, two donkeys for transportation, a saddle horse well equipped for your use. When visiting other places on the island, one has to use a horse or a donkey.

“Otherwise the farm produces most of what you may require for a living. What money is needed for clothing, fuel, and things like that, we obtain from the coffee plantation which surrounds the fruit garden. But you will get plenty of help at harvest time. The Norwegian consul in Guayaquil will help to sell coffee which cannot be sold on the islands.

“The house has two stories and an attic, and is equipped with both windows and mosquito netting. A cast-iron stove with an excellent baking oven is useful for making bread. Water tanks are located right by the kitchen door. It rains sufficiently, often during the night. Rainwater, which is collected from the roofing sheets, runs directly into the tanks and is not contaminated with dust.

“Besides chicken on the farm, I can provide enough meat from wild pigs. We go hunting several times during the week, mostly to provide cooking fat. In this way both hunting dogs and I get more meat than we need. I expect we can also get Ecuadorians for this kind of work.

“Bananas are the most common fruit and are produced in great abundance. They are fried or baked or used in other ways. From root vegetables or tubers we produce an excellent flour which is suitable for baking bread and cakes. Besides bananas there are plenty of oranges, lemons and figs in the garden. You can pick oranges from your window if you like!

“The house is situated at the edge of a terrace. From there you have a view towards the forest below, to the beach, and far away to the other islands, with their high blue mountains….”

Elfriede read this slightly camouflaged marriage proposal several times. After a short exchange of letters, she travelled to London to meet the plantation owner. On returning to Frankfurt she had a new surname and a Norwegian passport. She quickly packed her belongings and went on a honeymoon via Liverpool and Guayaquil to Santa Cruz.

The new Mrs. Horneman was at first taken aback at finding everything so wild and untamed. Villa Villnis was overgrown after a two-year absence, but the house was charming and the view as splendid as Jacob had said. Otherwise, she soon realized that life on Santa Cruz was slightly less romantic and a lot more demanding than the description in Jacob's letter of proposal.

German Elfriede Engelmann took out Norwegian citizenship when she married Jacob Horneman. The kitten is transported in a calabash. Photo, taken in 1958, courtesy of Emil Petersen, Oslo.

“Well, I'd better start,” said Elfriede. And later she adds:“After 20 years I still had not finished!” Free time was rare, vacations unknown. Trips to the beach were mostly with donkeys laden with what they were able to produce. Money was scarce except for the period when the Americans occupied Baltra. It was mostly a barter economy, items being exchanged with other islanders, and it remained like this until the late 1960's.

In 1940, Friedel was born on the second floor of Villa Villnis, and five years later Sigvart arrived. No midwife, no doctor, was present. With Friedel's birth, the parents became known as “Mutti” and “Vati” to everyone. Villa Villnis was out of the way but the house was always open to neighbors and guests. The social interactions provided some of the dearest memories.

Innumerable hikers, sailors, students and scientists have sat around in Mutti's kitchen. Here they have eaten homemade delicacies, discussed politics and religion with the stubborn Vati—or played chess with him upstairs. Some of those who have enjoyed their visit with the Hornemans include Thor Heyerdahl, Per Høst, Erling Brunborg, Roger Tory Peterson, Robert Bowman, Peter Scott, David Lack, and Farley Mowat.

It soon became obvious that Vati was an impractical dreamer, not very adept with tools and equipment. But he was good at getting others to do what he himself could not do, and he had the will and endurance necessary to survive and fight wilderness and feral pigs, mosquitoes, termites and fire ants.

Often when he left in the morning with his machete in hand he would also take along a book and pencil. Typically one would find him seated under a tree, deep in thought in meditation and busy scribbling in the margins. Vati was lucky to have found a woman who was used to hard work and who was also attracted to this independent life.

Håvard Henriksen from Hønefoss came to Santa Cruz early during World War II and married the Swedish woman Saimy, widow of John Lundberg. They built themselves a nice house surrounded by well-kept fields. They called the farm “Rancho Grande.” The two of them were vegetarians. Moreover, Henriksen was a fresh air addict. His bed was specially built so that he could sleep with his head protruding through a hold in the wall, protected against rain by an overhang of the roof, and with mosquito netting at the sides. When Saimy fell ill in 1960, the family moved to Norway. Håvard returned and tried chicken farming near Bahía Tortuga, but gave up and later on lived in the Canary Islands. Photo, taken in 1958, courtesy of Carl Emil Petersen, Oslo.

It was the fate of Galápagos-Norwegians that their children wanted to leave the islands. This was partly the parents' fault because always they talked about “Back home in Norway.” And May 17, the Norwegian National Day, was more important to celebrate than Galápagos Day, February 12. [May 17th commemorates Norway's adoption, in 1814, of its modern constitution. Instead of military parades there are children's processions with singing and bands.]

The children grew up accustomed to an environment of giant tortoises, huge wild boars, exotic forests, papayas and magnificent frigate-birds. They longed for the world they had read about in newspapers and weeklies, and which adults talked about. Vati was a masterful geography teacher. He made globes out of large calabash gourds and told of his search for diamonds in the Congo, digging for gold in Colómbia, and mining iron and silver on Svalbard.

Solveig Rambech, a good friend of Elfriede Horneman, married Anders Rambech in Guayaquil in 1936. After about 10 years on the chacra (farm) in the highlands, they moved to this house near Pelican Bay. Here Solveig feeds the chickens. Photo taken about 1960, courtesy of Elina Rambech, Oslo.

In 1964 Jacob became ill and his daughter Friedel accompanied him to the hospital in Guayaquil. It was crowded and expensive, so when Jacob was slightly better, they continued on to Norway.

Friedel never returned to Santa Cruz. For her, Norway was the dream land.

About the same time, her brother Sigvart also left Galápagos for good. He settled in California.

But Jacob wanted to go “home” again to Santa Cruz. As for Mutti, she somehow managed alone, even though her hip joints were failing. Jacob—with the help of his son Christian—obtained a room at Betania Sanatorium in Malvik near Trondheim, but considered himself far too active to remain a passive pensioner in Norway. For a long time the 75 year old tried to get a job. He was determined to work his way back to the Galápagos, but butted his head against regulations and complained about the red tape of post-war Norway.

A cash gift from the Norwegian Engineering Society was his salvation. In 1966 he was back on the islands. Mutti was standing outside Villa Villnis and waiting when he returned. With white beard and hair flowing he walked the avenue of avocado trees and coconut palms, which the two themselves had planted, and sang “It's a long way to Tipperary.” Mutti limped with two sticks into the house behind him, while she laughingly shook her head.

Scarcely three years passed, before the 79 year old Vati reluctantly had to face the truth. The two could not manage alone any more. His strength was failing, Mutti's arthritis needed medical attention, and both missed their children and grandchildren.

A life's work had to be abandoned. The property was sold, and in 1969 Elfriede and Jacob Horneman left Galápagos for good and headed for Norway and Finnmark. They settled with Friedel —whose married name was now Vonka— and her family. In 1976 Jacob's circle of life is completed. He dies in Karpdalen, Kirkenes, near the Russian border, north of the Arctic Circle, and not far from his childhood's Fruholmen Lighthouse.

| Left: Thor Heyerdahl's archeological expedition was mounted in 1953 because of a report of a tiki (stone statue of a diety) in the highlands of Floreana. When Heyerdahl and his group arrived they discovered that the head was sculpted, not by native Americans or Polynesians, but by Heinz Wittmer! They took the event in good spirits. The statue stands immediately adjacent to the pirate caves. The man in the picture is José David Rodriguez. He was a fisherman—originally with Bruun aboard Norge and later with Nuggerud aboard Dinamita. Photo by the author in 1985. | Right: He who laughs last, laughs best! The Heyerdahl expedition discovered abundant evidence of prehistoric visits, probably by Inca Indians who reached the islands in balsa rafts equipped with a sail and a retractable keel. In front: Eric Reed (USA), Thor Heyerdahl and archeologist Professor Arne Skjølsvold. Behind, their guides in Galápagos: Karl Angermeyer and Erling Graffer. Photo courtesy of Arne Skjølsvold, Oslo. |

| Left: Thirteen-year-old Sigvart Horneman beside the then old homemade sugar press belonging to Sigurd Graffer. Photo taken in 1953 courtesy of Erling Brunberg, Oslo. | Right: One of the calabash globes made on Santa Cruz by Jacob Horneman, now hanging in Friedel's home in Karpdalen (Karp Valley) near Kirkenes. Photo by the author in 1985. |

The Guldberg Family

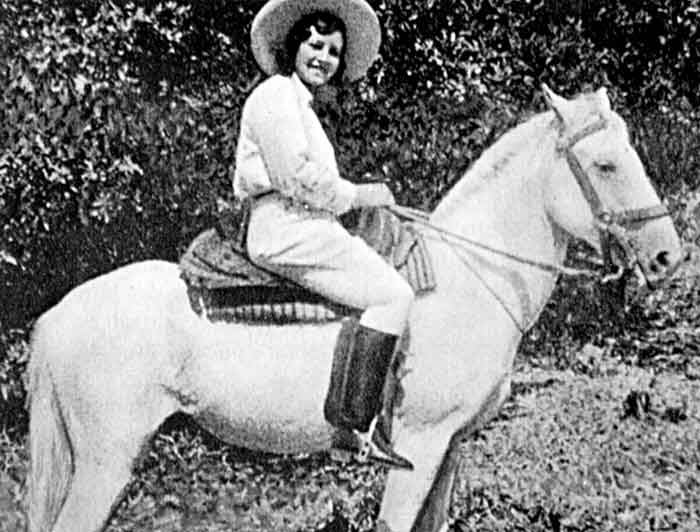

The youthful Laura Gulberg, whose maiden name was Hjerkin. After her death, the widower Thorleiv decided to emigrate.

The youthful Laura Gulberg, whose maiden name was Hjerkin. After her death, the widower Thorleiv decided to emigrate.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Christiania physician, Carl Johan Guldberg, worked as a missionary doctor in Madagascar. There, in 1880, he had a son who was named Gunnar Thorleiv. In 1889, after many years in the tropics, Dr. Guldberg was employed as a district doctor for Lesja and Dovre in Gudbrandsdalen in central south Norway.[Dovre is a mountainous area, home of “trolls” as in Grieg's “Home of the Mountain King” of Peer Gynt suite.]

Thorleiv wanted to become a farmer and as an adult he purchased Nordgard Hjelle farm in Dombøs, Dovre. Married to Laura Hjerkin, he had four children; Liv, Frithjof, Snefrid and Karin.

In the 1920's life on the farm gradually became harder and as the income decreased it felt more and more like pointless toil. Thorleiv came to dislike his work intensively, complaining about the harsh Norwegian climate and the cold, and dreamed of returning to his childhood paradise.

When he became a widower, he decided to make a clean break. He wanted to return to Madagascar, but now Galápagos fever was raging throughout the country. In the newspaper Gudbransdølen, Thorleiv saw the advertisement for Harry Randall's “Galápagos Expedition.” He discussed the matter with his children—who would like to accompany him to the Promised Land? [The Gudbransdølen newspaper, founded in 1894, was merged with Lillehammer Tilskuer as the Gudbransdølen and Lillehammer Tilskuer or G & L for short.]

None of them had married and settled down yet, and with the exception of Liv, shared their father's wish to emigrate. Liv was dedicated to her vocation as a nurse and wanted to stay. In spite of warnings from the rest of the family, Thorleiv signed on himself and his three children for Randall's 1926 expedition. The farm at Dovre was sold for 40,000 kroner. After paying mortgage debts and 12,000 kroner to the expedition, not much cash remained. Snefrid had saved some money, but most of it was also used when the expedition proved short of fuel and provisions. She became the sole women shareholder in the Albemarle company and the expedition secretary.

On November 3, 1926, Karin Guldberg's 18th birthday, Albemarle anchored in Wreck Bay, San Cristóbal Island. She looked upon the island as fate's birthday gift; and now it was her island; the fulfillment of a dream world of exotic plants, avenues of orange trees, and pampas where wild cattle and horses roamed. Here were beaches with buried treasures, possibilities for gold and precious stones in the untouched mountains.

Karin viewed everything on San Cristóbal as exciting and positive and ignored the shortcomings which annoyed most of the other Norwegians.

Old Man Dovre and the Russian