Drømmen om Galapagos

Stein Hoff

Part III

“Campo Noruego” on San Cristóbal

Lars Elholm from Bergen was among those aboard Albemarle who was most disappointed about Galápagos, and one of the first to return home to Norway.

In the Morgenavisen newspaper in Bergen on June 20, 1927, one reads about his first impression of “Las Islas Encantadas.” It is night on November 3, 1926. Exactly two months have passed since they left Færder lighthouse behind:

Fairytale Country —a Fata Morgana [a mirage]

“Finally the last night at sea; we would arrive at the island the next day. It was completely dark, as dark as only a tropical night can be. Very anxiously we went to our watches, waiting for the approaching dawn to bring us a glimpse on the horizon of our final destination, the island of San Cristóbal.

“About 3:30 in the morning the lookout announced that he observed something that looked like a dark thundercloud straight ahead. Through the darkness it seemed like a low dark cloud closing in with great speed. At the same time we were aware of a smell like rotten seaweed and the lookout thought we must be very near land, but the helmsman insisted there were still several hours to go before the island would come into view and that it was indeed a cloud.

“But only a few minutes later we heard the breakers roar like a storm and through the darkness we caught glimpses of white foam where waves broke against the shore directly in front of us. We could spit on the shore! Dramatic moments followed. ‘Hard to starboard!’ was called and at the last moment we managed to turn the ship and headed back out while waiting for dawn.

“With it came a proper view of the island—it was disconcerting—and now we understood that the fast approach was caused by a strong current which had driven the ship along at unusual speed. The cloud was in fact our fairytale country—San Cristóbal—and never during our entire voyage were we so near death as at the time we reached our destination.

“There it was, so very different from the tropical island we had imagined—no tall trees—no green grass—only bare, grey lava boulders along the entire shoreline, and higher up an intertwined jungle of thorny, ugly bushes. Disappointment was plain on all faces. We had staked all that we owned and gone through a lot of difficulties, but as we stood there looking at the island we understood that the difficulties were just beginning. And we did not have to wait.”

For all of Galápagos, 1926 was a dry year. The first months of 1925, however, experienced the El Niño † phenomenon, during which the westward flowing Humboldt Current with its cool upwelling water is pushed aside by the warmer water of the eastward flowing North Equatorial Countercurrent. Associated with this oceanographic battle of the currents are generally higher air and ocean temperatures, heavier rains and stronger winds than normal, and frequent flooding of the arid lowlands.

† “El Niño” in Spanish means child, i.e. the Christ child.

This climatic phenomenon, which occurs in all tropical regions of the world, but is especially pronounced in the Pacific, reoccurs on the average every seven years. This explains why there was luxurient vegetation around Post Office Bay when the Floreana arrived and Christensen's group was tempted to establish their base there. The watercourse, which they named “Wollebæk Creek” after the zoologist, was also the result of the El Niño rains. Before the colony gave up in autumn 1926, the men at Casa Matriz only once saw water running in the creek. During dry periods along the coast, nearly all herbaceous vegetation withers, Palo Santo trees lose their leaves and remain patiently in a state of dormancy until the next root-wetting. Sometimes they wait a year or more. When it finally rains, leaves, grasses and flowers appear almost overnight—a true metamorphosis—and one of the many remarkable natural phenomena of Galápagos.

The first few years after an “El Niño,” extra dry conditions generally prevail along the coast. The Randall expedition meets San Cristóbal at its driest.

When the colonists arrive in the highlands around Progreso they have a better impression of the island's potential. Up to now there is no rationing of fresh water from the crater lake. A spigot in the center of the village, where women wash clothing, remains open day and night, and the sugar factory, which consumes large amounts of water, is still in full operation.

Using the largest motorboat, six men and a pilot are sent to inspect the situation on Floreana, the island that Randall originally had chosen for settlement. Meanwhile, negotiations begin with Alvarado and Cobos about acreage on San Cristóbal.

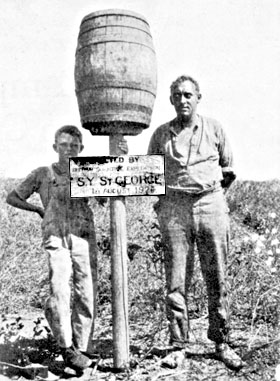

A party went over to Floreana to greet countrymen and to inspect the situation. Mate Gunnar Andersen from Nordstrand and the 12-year-old Rolf Pettersen from Oslo stand by one of the two mail barrels then at Post Office Bay. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

Otto Stöcker serves as interpreter. The mate from Isabela was offered a foreman's job by Alvarado and stayed behind on the island when Bruun sailed the cutter to the continent a few days earlier.

Alvarado's offer is tempting. Each colonist will receive free 20 hectares (50 acres) of fertile land a few kilometers above Progreso. They were also promised credit of 200 sucres for services and merchandise, free rent for two years, together with the opportunity to engage workmen and draught animals cheaply.

There is a requirement that between each plot of land, 50 acres be set aside for Alvarado. Norwegians would have first right to these plots for five years, and the price is set at fifty cents per acre. At first the administrators think that Alvarado is trying to cheat them with this clause, but Stöker explains that this is the rule, according to Ecuadorian law. On the whole it seems that the island's most powerful man is generally interested in the well-being of the Norwegians.

Young Cobos makes an especially favorable impression when he reveals his admiration for the Norwegian bard, Henrik Ibsen. From Randall he borrows one of the poet's works in English.

Manuel A. Cobos welcomes the Albemarle expedition to Galápagos. He strongly urges them to make San Cristóbal their terminal station. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

A week passes before a final decision is made and they continue to live aboard Albemarle. Meanwhile, smaller groups move around on land and water to explore the conditions, to fish, and to observe the strange environment.

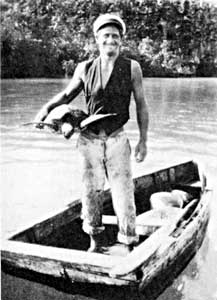

Molvin Knutsen from Ålesund is leader of the fishing group which keeps returning with exotic fish for dinner. When they have more than enough for their own use, they barter fish for meat and other commodities at the store in Progreso.

Sharks cause trouble for Knutsen and his men. These predators help themselves to the fish after they are hooked. Often the men haul only a fish head over the gunwale!

They shoot sea turtles with rifles before they realize that the reptiles must be caught alive as they otherwise sink or are lost. They also shoot a sea lion, but its flesh is not as palatable as the cheap beef available ashore.

The Albemarle people feel that Wreck Bay indeed deserves its name. On a shoal in the middle of the entrance to the bay rests the remains of the Turul, a large ship from Fiume, Austria. She had a large cargo of kerosene when the British sank her during World War I.§ So far attempts to salvage the kerosene have failed and the fuel continuously leaks into the bay. When the sea is calm, a thin rainbow-colored film covers the water in a wide circle around the wreck.

§ See the Ships Page for details and clarification of the fate of the Turul.

On the morning of November 11, the motorboat from Floreana returns and reports that everything there is dry and desolate. Only four Norwegians and some local workers remain in Post Office Bay.

Santa Cruz Island they had not bothered to visit at all as they thought a place with only brackish water or catchment of rain water unacceptable.

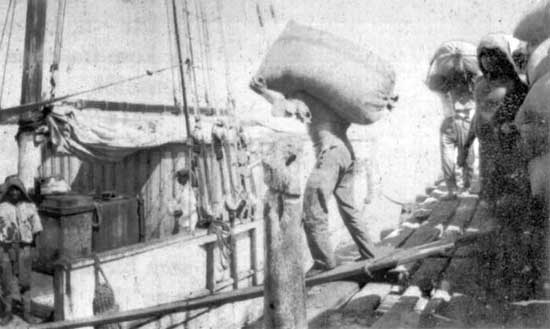

The four lifeboats were tied together in pairs, and the work of unloading the 14 prefabricated houses could begin. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

On their return they instead had an unexpected visit to another island. During the night the current carried the boat in the direction opposite to that estimated by the pilot. Hence they got an impression of Hood, an arid and relatively flat island south of San Cristóbal. This caused a delay of 24 hours and they considered themselves lucky in having taken along extra fuel.

At a meeting the same afternoon they agreed that if they are to settle in Galápagos, they must choose San Cristóbal where there is fresh water and at least some civilization. Another important reason for settling on this island is that the ship had only enough fuel for the return voyage to Panamá.

A large majority votes for San Cristóbal, their final destination: At last they can begin to unload the ship.

Randall breathes a sigh of relief now that his work is completed and his formal responsibilities over. For the time being, the mood is optimistic and in his favor. Now he hopes that the sale of the ship will be profitable and that everyone, including himself, can get back some of their investment. For lack of money before departure from Oslo, he had to put down 7,000 kroner for the ship, without receiving any shares or security. Besides, he has loaned a total of 1,700 kroner to various people aboard.

The unloading is done with two rafts, each made by joining two lifeboats with a deck of planks. This has been prepared in advance, and before sunset on November 11 they manage to get several loads ashore. But it proves to be more difficult than expected as the long wooden pier is so rotten that they dare not use it. Therefore, they cannot take advantage of the carts which run on rails from the end of the pier. Instead, they have to float the rafts as far up on the beach as possible, transfer the loads to carts in the water, and pull them up to a temporary storage on the beach.

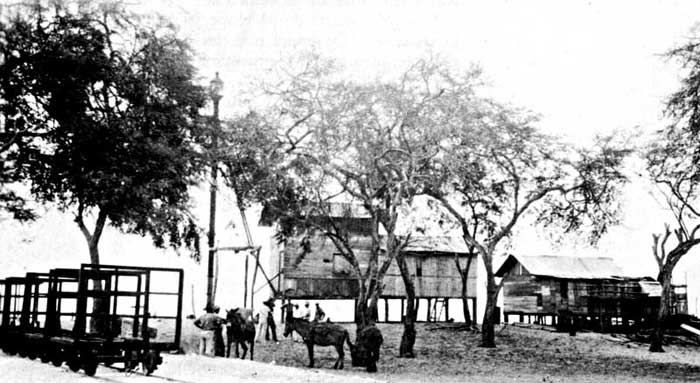

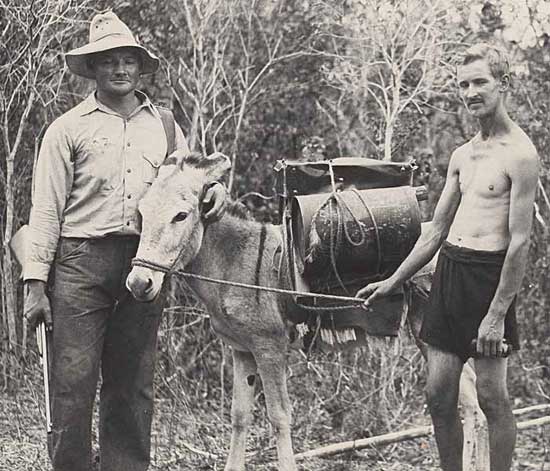

It was about 10 kilometers (6 miles) inland from the coast up to the plateau where Campo Noruego was to be established. To begin with, they used the tractor to transport equipment, but soon found out that it was cheaper and quicker to hire local men with teams of oxen to do the job instead. The carts were brought along from Norway. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

This operation takes ten days to complete. Meanwhile, others have begun to clear land in the highlands. Every adult who wants land receives his registered 50 acres. Between each plot of land, space is left for roads.

Einar Austlid is assigned the responsibility of drawing a map of this new village of square plots and 14 houses. They have already decided upon a name: Campo Noruega.

When the equipment arrives, at first dragged by tractor, later by rented oxcarts, it is placed beneath a temporary tent. The tent material happens to be canvas from the polar explorer Roald Amundsen's balloon used in his Spitzbergen expedition. Randall had obtained it from his friend very cheaply. So far it has been used for awnings and shower tents erected temporarily on the deck of the Albemarle, as auxiliary sails for the motorboats, and eventually as tarpaulins and tent ashore on San Cristóbal—a fate under the Equator which Amundsen could hardly have imagined for his Arctic balloon.

Wednesday November 24 Albemarle sails back to Panamá with its regular crew and a committee to supervise the selling of the ship.

While everyone else has moved into tents or temporary cottages at the beach and at Campo Noruego, Randall has lived these past few days as a guest of Manuel Cobos, Jr. Once again, the relationship to some of the participants has worsened—just when one believed that all quarrels were settled. There are accusations of inefficiency and greed. Randall's former friends in the administration, Stray and Andersen, have turned against him.

This criticism is related to frustration and disappointment about the land which was to shape their future. They re-read the many articles on Galápagos, including Randall's small book about “The Norwegian paradise on South America's west coast.” They demand an explanation. What has happened to the South Sea paradise?

Some weeks later, when Axel Seeberg is back in Galápagos and meets the Albemarle people, he is also shown what has been written in Norwegian newspapers in the Spring of 1926.

It is especially the newspaper articles in Tidens Tegn and Aftenposten, written by Aug. F. Christensen, that Seeberg finds incredible. Apparently he laughed until he cried, slapping his thighs, quite overwhelmed to think that anyone could describe the islands in such flowery terms.

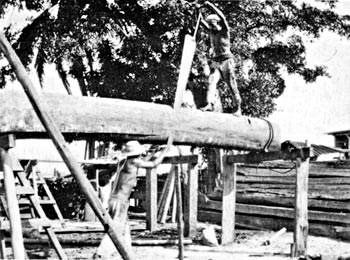

The local matazarno tree was excellent for house construction, but trunks of this size are not to be found in Galápagos. Photo is probably of a mainland tree. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

Randall cannot avoid becoming the scape-goat for those who feel betrayed. That he himself had been the object of biased information and thereby induced to paint a glorified picture of the archipelago's potential, may not be an adequate excuse. But that he was consciously cheating is most unlikely. If this were the case he would hardly have come along on the expedition and planned a coffee plantation for himself.

Randall cannot live and work among people who accuse him of cheating. He is deeply hurt by the criticism and decides to return home as soon as possible.

Like the rest of the village on San Cristóbal, the Progreso sugar factory was founded by Manuel J. Cobos. When it was built in the 1880s, the factory was very modern. Photo courtesy Nette Næss.

Martin Skaraas, who comes over from Santa Cruz to barter canned food and greet his fellow countrymen, provides this impression of the situation on San Cristóbal after a few month's activities:

“In this colony it is very lively. Not like it is with us where everything is peaceful, for here they fight every day. They have had trouble ever since they left Norway, and they have been terribly cheated. Hjorth relates that when they arrived here, Randall went ashore alone, met with Alvarado and Cobos, and without conferring with the others, arranged to receive 200 sucres for each contract that was made.

“Although here there are between 50 and 60 thousand wild cattle and thousands of pigs, they had to sign an agreement not to hunt but to buy meat from Alvarado. They were given land high up where nothing grows. Then there were protests, so that Alvarado had to grant land in the fertile belt, and now they have to dismantle the houses and move again. This is a terrible chore so most of them will leave. When Randall came aboard the ship to travel to Guayaquil†, they threw him into the sea, so he was obliged to live at Cobos' until the local schooner returned and he could go on the next trip. He dares not live on the island, as the Norwegians who are left would have shot him.”

† Skaraas makes a mistake; the ship returned to Panamá.

Randall indeed wants to leave, but—according Skaraas—the crew of Albemarle refuses to take him along. He has to wait until the next shipping opportunity eastward but takes the opportunity to get to know the island and its inhabitants. Skaraas' comments must be read with a certain amount of skepticism as rumors and gossip flourish in this community completely devoid of news media.

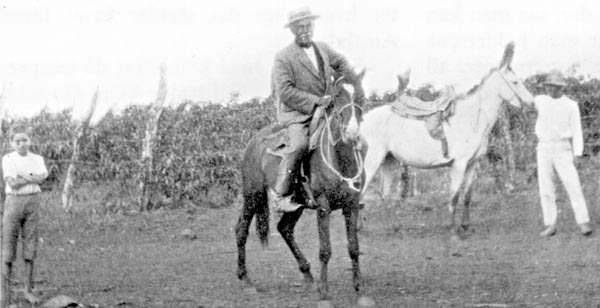

Randall enjoys a growing friendship with his host, Manuel Cobos. Every day they go riding together, and in the evening they play chess and talk. Cobos insists that Randall be his guest and stay in his house as long as he wishes. When Albemarle sails, Randall writes in his diary about his frustrations regarding some of the crew and expedition members:

“At 1 o'clock today, Albemarle left for Panamá with the following crew: Captain Deetjen who gets drunk whenever he is ashore; first mate Andersen, who drinks anything others pay for; second mate Lund, arrested by the police when we were in Las Palmas because of drunkenness and disorderly behavior; steward Lunde, former choir singer at the Opera Comique Oslo, an incurable and brutal drunkard who was arrested in Panamá; third mate Bjørnstad the same; he jumped overboard while drunk in Las Palmas; fully dressed and with his pipe in his mouth, he swam around the ship. As a result of that he developed pneumonia. Jørgen Bjørnholdt, disowned by his family on account of drinking. Guttorm Pettersen, also whenever possible went ashore and returned drunk and unable to work; he was paid off recently when, in his usual state again, he refused to work.

“Ship owner Stray gets dead drunk every time he has money; on our voyage he served as third engineer. Luckily, the two other engineers, Musikka and Stokkevaag, are decent people, as are the two assistants, but God forbid, what a crew!

“I do hope they find their way back. Moreover, K. Pettersen goes along as carpenter and member of the sales-committee. The other members are Stray and Andersen. When the ship left, some shots were fired from a revolver and a few rockets were sent skyward.”

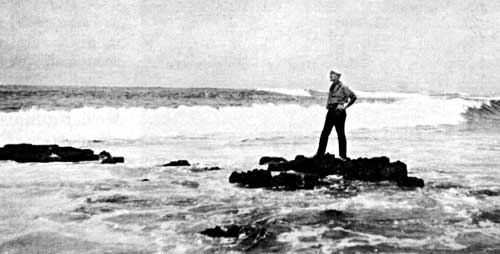

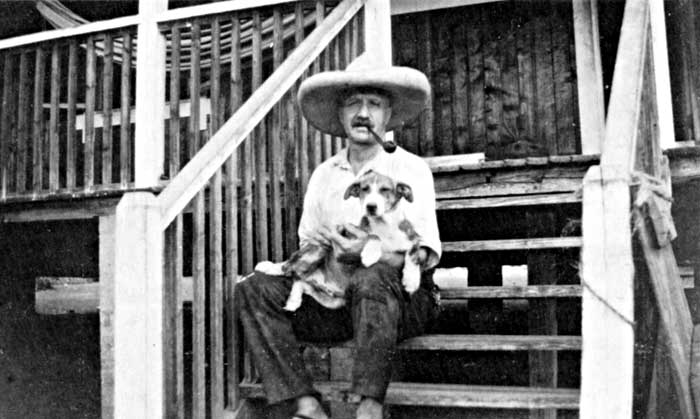

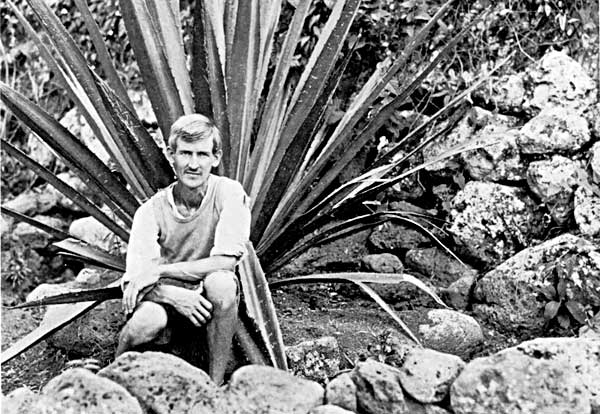

When Albemarle sailed back to Panamá, Harry Randall moved in with Manuel A. Cobos. Nearly every day he went riding with his host. Photo courtesy Sylvia Randall Andersen.

Randall has only about three weeks ashore, but stays long enough at Cobos' house to obtain a good impression of the daily life of the island's upper class. There is no lack of affection and friendship, but he is taken aback by the general disorder, lack of maintenance and poor hygiene. He is also concerned about the way the domestic animals are treated. Donkeys' saddles resemble wooden trestles turned upside down. Where the wood rubs against back and loins, the hide is often chaffed through, leaving large sores where flies abound. About the shops he writes:

“In the two or three company stores found here, merchandise is never wrapped. The buyer always has a piece of cloth at hand and wraps sugar in one corner, flour in the other, salt in a third, and corn in a fourth. At the butcher's, where cattle are slaughtered just outside, the meat is sold while still warm. The blood is lapped up by the roaming dogs and pigs, and when the animal is tied to be slaughtered, all the dogs in the village gather to partake of the feast. I found it so horrible to watch that I had to get away because I felt like fainting.”

The daily work routine and meals are also described. The servants' hygienic standard is unimpressive.

“Lack of cleanliness is simply comical. Instead of washing wine glasses, the cook empties the remains on the floor, dries the glass with his fingers or with a dirty towel and afterwards places it upside down, back on the table, which remains set day and night. The tablecloth is an oilcloth, tacked in place at least three years ago.

“Wine and spirits are always at hand. Walls and floors are not tight, air passes through the cracks, and when one sweeps the upper story, dust falls down into the office and shop downstairs. All kinds of dirty people come and go upstairs on different errands. The communal water toilet is in a room without a door, so one risks being interupted by a lady while in the middle of one's intimate business; therefore I prefer the green woods. Incidentally, whatever somebody does in the room can be heard all over the house.”

Two of the original Campo Noruega houses were later reassembled as one large house. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

One may wonder what has happened to the high-class style described by Per Bang and Ludvig Næss. Possibly it has something to do with the eyes of the beholder? Nevertheless, Randall has a splendid time thanks to his amiable host. He begins to regain some of the 10 kilos (22 lbs.) he lost during the voyage. And he sleeps well. The only thing that keeps him awake is when the 200 or so village dogs fight beside the house. But no one else seems to be bothered by the ear-splitting noise.

On December 3, Harry Randall leaves Galápagos a bitter man. He still has plans to establish a coffee plantation on his 50 acres, but since it takes four to five years before one can begin harvesting, he hopes that with Cobos' help, he can initiate his project while remaining in Norway.

In Guayaquil, therefore, he pays a visit to Governor Ribadeneira to acertain if the contract with the landowner Rogerio Alvarado will be honored. But the information which Randall receives makes him stare in disbelief at the governor. According to Ribadeneira, Alvarado never owned either the cattle on San Cristóbal or the land at Campo Noruego!

The 14 houses on San Cristóbal are not ready for occupancy until after the New Year. Considering that they not only have to be constructed, but first be transported, bit by bit from Albemarle to the beach, and thereafter be drawn by oxcart 10 km up to the highlands, partly over roadless terrain, it is a remarkable accomplishment to have built all the houses within 2 months.

As the work progresses it is marked by festivities. Einar Austlid writes as follows:

“One house group had a garland party when the rafters were up. They had purchased a sack of sugar, brewed and distilled it. During the evening they came like a herd of oxen, hooting and shouting, from house to house, and offered their ware. It was a noisy crowd, like New Year's Eve in Old Norway. The locals thought the devil had arrived and was finishing off most of us!”

As on Santa Cruz Island, as soon as the contracts are signed, land is cleared and crops planted.

Karl and Ragna Aune from Malvik display a selection of exotic fruits and vegetables. In the background is Karl's 73 year old mother, Kirsten. To the right is Einar Austlid, a teacher from Ørsta who lived with the Aune family in the newly-constructed house at Campo Noruega. Photo courtesy Einar Austlid.

With Christmas approaching at Campo Noruego, one would have expected to see vegetables in the various fields, but this is not the case. They realize that local conditions are unsuitable for Scandinavian seeds. If anything sprouts, it attracts a small red ant, which seems to thrive on Norwegian crops. Valuable corn produces next to nothing. Only tomatoes thrive, but they in turn are very popular with the island's many wild pigs.

The first potato harvest also is the last one. Austlid writes that “potatoes are no bigger than gooseberries, and other vegetables have not come up at all. Only yucca is thriving.”

Yucca is a tuber which can be served as a vegetable, or can be grated, dried and made into flour. But most of the settlers are not willing to change their traditional eating habits, and neither yucca nor other local crops are popular. This is a major reason why so few Norwegians succeeded as farmers.

Drinking, which was a problem during the voyage, continues to be an embarassment for the colony, although it is only a small hard-core group that is responsible for transgressions. Strangely enough, nobody is killed or seriously injured during drunken brawls and shooting practice.

Nevertheless, the San Cristóbal colony experiences one death during the first year. Kirsten Aune contracts dysentry and dies at nearly 74 years of age. On the other hand, two babies are born. The first little Norwegian sees the light of day on Galápagos on January 9, 1927, and is given the name Erik. The parents are Eugenie and Arnulf Greiner from Kirkenes, a small town north of the Arctic Circle.

Expeditions that were never realized

The Floreana, Ulva, Alatga and Albemarle expeditions had at least one thing in common, they got underway.

While Galápagos fever ravaged among the unemployed willing to travel, there were many others who planned on buying a ship and sailing off to the “Norwegian Paradise on the South American West Coast.” Four of these expeditions were reported in the newspapers. However, no journey ever materialized although in one case members moved aboard ship and were ready for the voyage.

In the 1964 book Mr. Petter's Trumpet, author Olav Nordrå recalls how, in 1926, he and his parents rowed and sailed in an “åttring”—a small eight-oared undecked boat—south from Helgoland in the county of Nordland in northern Norway. The plan was to join one of the Galápagos expeditions. During their slow and hazardous trip along the coast, they heard rumors to the effect that the expedition was troubled by fraud and deception. As a result, they abandoned their effort in Trondheim! The title of the book refers to a beloved Nordland poet, Petter Dass (1647-1708), who in his great epic Nordland's Trumpet, has the following verses of inspiration. (In Norwegian, the lines rhyme.)

In our area we produce neither grapejuice nor wine,

in our mountains and hills silver ore is not likely to be found.

We have no goldmines red.

Because we do not live in the land of Canaan

where milk and honey flow like water,

by us there are no grapes for picking.

They shouted and made a terrible noise;

we need to borrow, we are starving to death,

our stores are severely depleted.

And if you do not alleviate this our emergency state,

then you force us to go and pawn the very last of our belongings.

And this is exactly what they did—as did so many others who wanted to go to Galápagos. The cover illustration is by another Northland man, Kaare Espolin Johnson.

The Hedvig Project

In the Tønsberg newspaper of March 15, 1926, there is a report of a marine lieutenant Dehli who has purchased the 800 ton motorship Hedvig. She is berthed in Moss and will combine transport of immigrants with a cargo of dynamite destined for northern Chile. One month later, Hedvig is also mentioned in a note in Sandefjords Blad but later nothing is heard of her.

“One expedition after another…”

Sandefjord's newspaper June 14, 1926:

“It will surely not be long before the Galápagos Islands are overpopulated by Norwegians if the Galápagos fever lasts much longer. Sandefjords Blad received news today that a new expedition is being prepared for the popular islands. Leaders will be O. A. Olsøn Lunde and Captain Bornholt of Oslo.

“The expedition will be ready to leave on the first of August. There will be about 80 members, several of whom will be accompanied by their families. This expedition will also take along equipment for a canning factory. The expedition has secured a first class steamer of about 1300 tons.

“One expedition after another is organized and thousands await their turn. As long as one stays with the man who first started these expeditions, all should go well. But it appears to us that too many leaders of diverse qualifications show up. Galápagos is no Klondike.”

True enough. This last comment is probably a quote from the Ecuadorian consulate, i.e. Christensen's office, and it is no surprise that Aug. F. himself is worried about the situation. Consul Bryhn has issued a warning to the Foreign Office that the Floreana expedition is in deep financial difficulty. What later happened to Lunde and Bornholt's ambitious plans is not known. Most likely a financial reassessment made it clear that an individual capital investment of 3000 kroner was unrealistically low.

Eilertsen tries again

Cut out. To Galápagos. Watch for the opportunity.

A group, who in the near future plans to sail to Galápagos in their own ship, can take a few persons as passengers to Santa Cruz, Galápagos, in order to exploit the considerable opportunities there. Every person (women as well as men) is given completely free 200 maal (50 acres) of extremely fertile land, as well as hunting and fishing rights. Captain of the ship, O. Eilertsen, as is well known, has earlier successfully guided some colonists to Santa Cruz, and after a 4-months stay there, has gained a detailed knowledge of the region's great opportunities. The rights of every colonist can safely be expected to be taken care of in the best possible way. The cost is kr 1200, which includes full board and lodging aboard the ship for at least 14 days after arrival. Every person may bring up to 5 tons of luggage free. Join quickly. For more information, send kr 0.20 in stamps to C. G. Gujkild, Nytorvet 5, Oslo, tel. 12765.Olaf Eilertsen's return home caused a lot less fanfare than his cheerful departure. Østlandsposten of March 10, 1927 has the following short note:

“Captain Eilertsen, who left this Spring with the Ulva expedition, came back on Monday aboard Kong Dag from Hamburg. He is apparently trying to find a vessel with which to sail to South America to engage in coastal trading and possibly establish a route between the continent and the Galápagos Islands.”

We do not hear more about Eilertsen's new plans until the month of May. Saturday May 7, 1927, Tidens Tegn reports the following:

“Preparations are now being made for a new expedition to the Galápagos. Leaders of this project are Captain O. Eilertsen, who last year led the Ulva expedition to Santa Cruz, and C. G. Gukil.

“The plan is to buy a steamship which can accomodate some passengers. A cooperative enterprise, such as in previous arrangements, is not being contemplated. A ship has not yet been purchased because they want to see what the passenger response might be.

“The expedition will stay a while in the Galápagos Islands in an effort to generate coastal trade between the islands and the continent. Should a larger ship not be suitable for this kind of transportation, the purchase of a motorschooner of 100 to 150 tons will be considered. The intention is to establish a market which has a regular supply of Norwegian products, since it is well known that one of the most difficult problems is the lack of regular contact with the continent.”

After May 1927 we find no more newspaper reports about Eilertsen's new expedition. But the plan for a 100 ton freighter was sound; the previous ships had been too large and too expensive to operate. Eilertsen still feels responsible for his friends on the islands. He doubts that Bruun's small sloop alone can adequately handle freight to and from the colonies. In late October, he had personally witnessed how a rather small load of canned goods shipped by Bruun to Guayaquil was affected by sea water. Several cases were damaged by rust and had to be sold cheaply. Future transport of bacalao would be in vain if the products could not be stored under absolutely dry conditions.

It is Gudrun Eilertsen who persuades her husband to abandon all future Galápagos plans. She is happy to have her husband home and alive, but is also worried about his mental health. He is depressed, has problems of concentrating and again suffers from severe headaches. That the economic situation is poor does not improve his condition. They agree that the family will have to endure scandalous gossip in their home town rather than start getting involved in new and stressful projects.

(For the next few years it is Gudrun Eilertsen who provides the family income while her husband is unfit for work because of his nervous condition. Their two small sons are teased and nicknamed “The Galápagos boys.” Gudrun earns most of her income as a dressmaker, but in 1934, this remarkable women receives the Coastal Master Certificate in Sandefjord, becoming the first women to do so. She receives a grade of 2.90, i.e. excellent! However, she never actually works as a coastal skipper. Olaf Eilertsen's condition has slowly improved and he is now employed as captain on the coastal liner Anna N. from Larvik, a position he retains until his retirement. Once more he is one of Larvik's respected men. In 1954, when he celebrates his 75th birthday, Østlandsposten has a very favorable article about him.)

Robinson Crusoe

Sigvald Strømme was a lawyer and real estate broker in Oslo. Apparently he planned to join Harry Randall's expedition before settling in favor of his own enterprise. He invited investment in a cooperative company, patterned after Randall's model, and soon received 500-600 applications. At the end of May 1926, when he had 60 members committed, he and Captain T. Gundersen Welhaven bought the sister-ship of Albemarle, the 1000-ton ferro-concrete ship Fjeldtop. Like Randall's, Strømme's expedition was to sail in July.

It was decided to equip the ship in Porsgrunn. This is some distance south of Oslo, but Moss, Tønsberg and Larvik were all busy with other Galápagos expeditions, and Vippetangen quay in Oslo was reserved for Randall.

The name Fjeldtop (“Mountain top”) was changed into something more appropriate for an expedition ship sailing from Norway to the Pacific. It was re-christened Robinson Crusoe!

The abundance of wild pigs and cattle―or as shown here, turtles and sea lions―were fascinating features. Drawings by Jacob Sømme in Alf Harbitz' book Mandskapet fra Bark “Alexandra” (The Crew of the Barque “Alexandra”).

Problems and delays follow in turn like pearls on a string. By the beginning of September Robinson Crusoe is still moored in Porsgrunn harbor. The number of members has increased to 80. Since August, thirty of these have lived aboard ship to help with preparations, and simply because they have no other place to live.

The plan now is for the ship to sail at the end of the month. On Wednesday September 8, the Porsgrunn Dagblad has a report on how the expedition is faring:

“Yesterday one of P. D.'s reporters made a call on Captain Gundersen Welhaven and confronted him with Consul Bryhn's warning about leaving for the Galápagos. However, the captain responded by presenting a report dated December 15 of last year and signed by Consul Bryhn, in which he praises Galápagos and Ecuador in glorious terms and confirms that on the islands they grow bananas, oranges, etc.… and most types of grain. There is fine pastureland suitable for raising cattle. The climate in the islands and the highlands is extremely pleasant and healthy. The statement finally declares that hardly a country other than Ecuador and Galápagos can offer such good opportunities. This contradicts recent statements by the Consul, the captain points out, and we find his conduct strange. Meanwhile, we shall depart in good spirits because the reports which arrived from earlier expeditions are satisfactory.”

At the same time that the reporter of the Porsgrunn Dagblad interviews the captain aboard Robinson Crusoe lawyer Strømme, in an Oslo court, is accused by the Department of Social Services and the Oslo Police of breaking emigration rules. In May he had received several complaints about irregularities, as did Randall, but the lawyer argued that since the first expedition was not stopped by the police, he refused to change his plans. Thus he chose to have his case tried in court.

According to the Social Services Department the law ruled that in order to act as an agent in matters of emigration, written permission from the police was required. The purpose of the law was to assure that emigrants arrived safely at their destination with a minimum of problems. Among other things the agent should have had full understanding of facilities and opportunities in the country of destination.

The Department goes on to explain that this expedition has neither a detailed statement nor a plan, including how money is to be managed. The Department declares that Strømme not only has taken the initiative for an expedition, as he insisted, but also has taken a decisive step, because he let people sell home and farm. Unlike Randall's expedition, there is no detailed statement about this matter, there is no plan and a minimum of documents. It is not known who is responsible for the money. “Strømme is everything—the others nothing.”

To everybody's surprise, Strømme is acquitted. He also receives kr. 100 in compensation.

Now there should be nothing to hinder Strømme from taking his expedition and sailing at the end of September, as announced. But Fall soon passes with the concrete ship still in the same place. Originating from Myhre's News Agency, the same article appears in several of the country's newspapers on Tuesday November 30:

“Since August, lawyer Strømme's ship for his Galápagos expedition, the Robinson Crusoe, has been moored in Porsgrunn. The expedition consists of 30 persons; family providers, women and children 4 months of age and older. There are only a few kroner left of the capital contributions, and since the purpose was to emigrate to the tropics, the members have sold everything that is needed for wintertime and at present they are without means to cope with the future.

“A request is made to the Social Welfare Department for State assistance in one form or another. Meanwhile they will try to use the ship as a freighter during winter, with a departure for the Galápagos possibly in the Spring.

“Director Welhaven of the Social Welfare Department confirms to Myhres News Agency that the expedition participants have applied for help and that the issue is being considered. But in a situation like this, there is little likelihood of obtaining support; one must be prepared for a rejection. The Emigration Law is currently under review in order to protect participants of expeditions like the one in question.

“The Norwegian Directorate of Shipping and Navigation informs this agency that one cannot issue a sailing permit for a freighter unless there is a sufficient number of officers aboard. One has to provide a captain, a first mate and an engineer, in addition to a couple of able bodied sailors among the crew. Up to now there are none. The ship, which is built of concrete, has been inspected and is in good condition.”

Vestfold Fremtid, December 2nd:

“The Galápagos ship Robinson Crusoe has left Porsgrunn. There is great secrecy about its departure. For the time being, the ship will sail as a freighter along the coast. The entire crew, women and children, are aboard. The expedition's leader will provide no information about future plans or the ship's destination. It is possible the ship will sail to the Galápagos in the Spring. The participants have settled all debts in Porsgrunn.

“According to news from elsewhere, the ship left for Fredrikstad, where she is berthed and will receive coastal cargo. Some of the women and children aboard were sent ashore in Porsgrunn and those remaining aboard will leave the ship in Fredrikstad, where in the meantime, living facilities are provided. The idea was to keep the ship busy during the winter with the help of the 12 male members of the expedition, so that they could provide for their families left ashore.

“Initially, the ship sails with empty barrels for Bodø, north of the Arctic Circle!”

One week later, another story about the scandal in Porsgrunn appears in the newspapers. The expedition members themselves have charged Strømme with fraud, and all relevant documents have been sent to the public prosecutor.

Two books that describe the Norwegians' adventures in Galápagos: Alf Harbitz' The Crew of the Barque “Alexandra” (1915) and Ola Mjanger's children's book Settlers in Galapagos (1936).

One person—a single man—from this expedition finally arrives in the Galápagos. He worked his way across the Atlantic, through South America, and eventually arrived in Santa Cruz in February, 1929. His name is Johansen.

Like Floreana, Santa Cruz gradually becomes depopulated. Even Johansen is unable to stand it for long. We do not know his first name, or where in Norway he originated, but on Santa Cruz he becomes immortalized with the nickname “Grise-Johansen” (“Pig-Johansen”). The story goes that he kept Norwegian pigs in a corral and let them run free when he left.

The pigs thrived and by the 1930's they had become a large and feral herd. For a long time they were an important food resource for Norwegians and other immigrants, especially the boars weighing 200-300 kilos (400-600 lbs.) and armed with huge tusks. These feral swine are fierce animals that show little resemblance to their domesticated ancestors.

Except for the story about “Grise-Johansen,” it has been impossible to trace the fate of the other 30 unhappy persons who lived aboard Robinson Crusoe in Porsgrunn harbor for 3 to 4 months in the Fall of 1926.

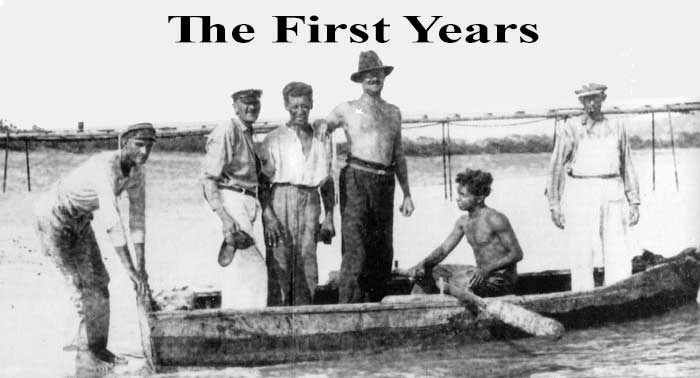

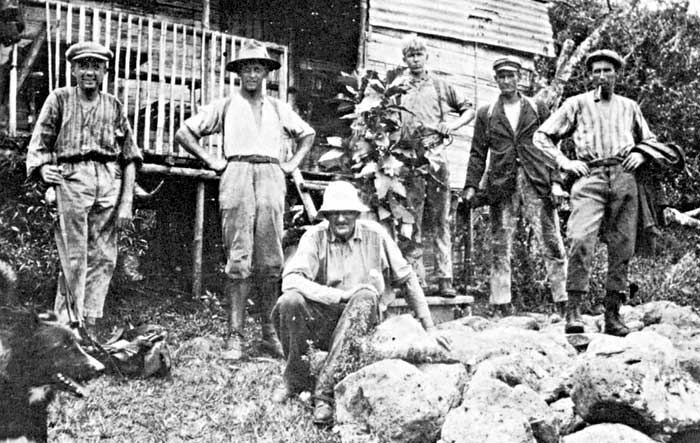

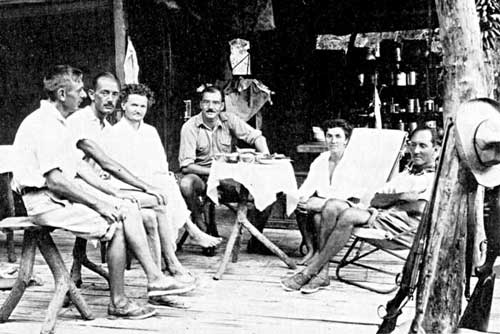

At Post Office Bay, 1927. From left: Kristian Stampa, Paul Bruun, Henrik Lund, Thorolf Østmoen and Karl Pettersen. Seated rower is unidentified. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

Between the summer of 1925 and the Fall of 1926 the human population on the Galápagos Islands grew from about 400 to about 550 persons, an increase of nearly 40%. The 150 new settlers were Norwegians who experienced a long and painful voyage to reach their destination. For all intents and purposes, they were financially hard up, but they were healthy and had their belongings intact. If Galápagos had really proved to be the paradise that they were led to believe, then our story about the Norwegian immigration would have ended with “…and there they lived happily ever after.” The remainder of the story would have been too boring to justify space between the covers of this book.

But it did not happen this way. For most of the Norwegians the voyage had hardly begun. These people would be dispersed over all the mighty American continent, from Argentina and Chile in the south, to Alaska and Canada in the north. Some also moved to Australia and Africa. Here they found work, friends and excitement, maybe a sweetheart and a permanent home. Others found an all too early grave. Many returned to Norway after a shorter or longer period of time.

It is interesting to note, however, that of all those who gave up the original plan for a Galápagos future, only a few remember their stay with bitterness. The Galápagos expeditions were good adventure, in spite of everything else.

Some were firmly committed to not give up. They thrived on life's harsh demands on these palmless, sun-dried islands in the Pacific. There were not many, and the few became fewer each time Galápagos revealed itself not only as an enchanted, but a rather bewitched and cursed place, which claimed her victims mercilessly.

Before three years had elapsed, there were three crosses with Norwegian names marking the graves at Academy Bay on Santa Cruz Island. Additionally, we have the following gloomy statistics for 1929 concerning the fate of the Galápagos expeditions:

From Floreana no one remains.

From Isabela; only Paul Bruun, who is now skipper aboard the local schooner Manuel J. Cobos.

From Ulva; Gordon Wold and Kristian Stampa. They fish together from their base at Santa Cruz, but also live part time on Floreana.

From Alatga no one remains.

From Albemarle; Thorleiv Guldberg with daughters Karin and Snefrid and the couple, Ruth and Alf Ødegård. Of the former fishing party only Trygve Nuggerud and Erling Jenssen remain.

And Johansen from Robinson Crusoe has freed his pigs and has also left. So only nine of 150 persons of the original expeditions settled in Galápagos, ten if we also count Bruun.

What is the reason for this development? Let us look back to the Fall of 1926 and the activities in the three Norwegian colonies on Floreana, Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal.

Floreana

In the autumn of 1926 the fate of the Norwegian colony at Post Office Bay is already sealed because of the isolation, lack of water, and a hopeless economy—the men will return home. In early November, Axel Seeberg cables from Guayaquil to Sandefjord asking for travel funds for eight persons. Some of these eight are former crew members of Floreana, which was recently sold in Ecuador to a Colombian shipping company. Three or four men remain at “Casa Matriz” to take care of the company's property, waiting for the whaling expedition Atlas to arrive. But faith in Atlas weakens gradually. This whaling factory ship was expected in February, now seven months past, so they eventually decide they may as well sell the little steam engine from the electric plant to the factory at Santa Cruz. As a result, the Floreana colony loses its old luxury—electric light.

When Seeberg and Bruun arrive with Isabela on Christmas Eve, 1926, they bring parcels and mail from home, tobacco and provisions, even beer and liquor, but no good news about Atlas. Christmas sentiment takes on the mood of a funeral.

Those few remaining from the Floreana colony sail with Isabela to Santa Cruz to celebrate New Year. Some days later, in January 1927, the last members of La Colonia de Floreana leave Galápagos.

Occasional attempts to settle on Floreana during the next two years are unsuccessful, and after August 1928 there are no human beings; only memories are left of the first Galápagos expedition from Sandefjord.

On Thursday April 7, 1927, Vestfold Fremtid prints the following story across its front page:

“Finished with Galápagos”

“It was Aug. F. Christensen who started the Galápagos fever and formed the first whaling company Atlas, which was to be hunting off the paradise's shores. Recently the whaling company was dissolved before it had made a single catch. Also of late, the company, La Colonia de Floreana, decided to wind up its affairs, and has decided to sell its land on the island of Floreana. All that remains is to find buyers. Make an offer!”

From the April 7, 1927 Vestfold Fremtid (“Vestfold Future”). There is a subtle tone of mischievousness in the little article, which is translated above.

That the labor party newspaper Vestfold Fremtid displays a jeering style, while the conservative Sandefjord Blad does not mention anything, is hardly coincidental. Naturally enough, Aug. F. becomes unpopular among his friends who are left holding worthless shares. In a scrapbook and a photo album he keeps the memories of the exciting experiment to himself, and otherwise talks very little about his personal involvement with the Galápagos project.

Christensen continues until 1935 as Ecuador's consul in Norway. This year he turns 50, an event that is noted in newspapers all over the country, but nothing is said about the Floreana expedition. Later he does much traveling, lives for a while in Spain and Morocco, and participates in the drafting of maritime laws for Ecuador. In 1940 he apparently earns a doctorate in political science at Western University in Delaware, USA. After World War II he settles in Åsgårdstrand where he becomes mayor and is still remembered as the instigator of the “Åsgårdstrand Days.” †

† Åsgårdstrand Days is an annual summer festival in this seaside village and popular summer resort near Horten in Vestfold. The painter Edvard Munch lived here.

Aug. F. Christensen dies in 1959. His length obituary mentions nothing about the Floreana expedition.

Axel Seeberg was now given the responsibility of selling the remaining installations on the island. Seeberg in many ways resembled the skipper of Isabela, Paul Bruun. He had the same education and was about the same age. He is also remembered as a person of exceptional charm and imagination, full of ideas and visions; extrovert and original. He wrote poems when he was inspired, and was the life and soul of any party.

Contrary to Bruun, Axel Seeberg has nothing in Norway that he wanted to escape from, but in 1926 he becomes involved in a network of unfortunate circumstances in Ecuador. With his strong commitment to Floreana as a commercial whaling station, he is shocked to learn that the company is dissolved. When this bad news reaches him in March of 1927, he has accumulated a sizeable personal debt in Guayaquil. And it continue to grow.

He clutches at straws hoping to sell Casa Matriz † and other valuables on Floreana. For him this is a difficult task, especially regarding the house. It was he who in 1925 personally supervised its construction using the same design which he employed when building a house for his family and himself on the island of Hvalø near Tønsberg 14 years earlier.

† Casa Matriz still existed as recently as 1966, but today (2006) all that remains are a few cement foundation pedestals, which may be seen beyond the Post Office barrel on Isla Floreana.

But the authorities interfere. Some of the original conditions have not been fulfilled. Among other things the company committed itself to build a better pier, a lighthouse and a governor's residence at Post Office Bay. Failing to do so, all the company's properties would revert to the Ecuadorian state!

With the frequent changes in government, much can be “arranged” through contacts and bribes. But as he cannot find any potential buyers, Seeberg will have to abandon this tactic as well.

Ecuador's economy in the 1920s and 1930s was extremely poor. Still, the ever-changing governments resisted the temptation to sell or lease Galápagos to the USA. However, Axel Seeberg and other Norwegians were hoping that this indeed would happen so that communication and trading facilities would improve. The cartoon by Jaime Salinas below the “Kaleidoscope” heading is from a 1939 Guayaquil newspaper, but illustrates a situation also prevalent a decade earlier. The cartoon is captioned “Temptation: Necessity is bad counsel.” Courtesy Jacob Worm-Müller.

What about Isabela? The old pilot sloop that he personally purchased in Norway belonged to the company. Because his debt was accumulated while working for the company, Seeberg feels that the boat should be his to use, either for carrying cargo like Bruun does, or for raising cash by selling her.

Bruun refuses. Did he not personally finance repairs at Madeira, Colón and Guayaquil? Without his support the sloop would never have arrived. Now that the company is dissolved he cannot recover his expenses either—hence the ship belongs to him!

Seeberg contacts a lawyer and reports Bruun. In August, after only ten months of freighting, the sloop is confiscated and Bruun is forced to stop his activities. The Isabela remains locked up in the harbor and starts to deteriorate.

By February 1928, Bruun has won two legal challenges but Seeberg will not consent and appeals to the highest court.

From “Camp Morten” on Floreana. Bruun is in the foreground. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

The dispute over Isabela does not seem to undermine the friendship between Seeberg and Bruun. Between legal maneuvers and sales negotiations in Guayaquil, they play bridge together almost daily. One evening Seeberg does not arrive as arranged, but when he turns up next day, he relates how he had to spend the night in jail! The reason for his detainment concerns unpaid hotel bills totalling 750 dollars—about 3000 Norwegian kroner—a significant amount in 1928. The man who arranged Seeberg's release is Arthur Worm-Müller from Albemarle, and newly-appointed Norwegian Vice Consul. Consul Bryhn, residing normally in Quito, was so tired of all this travelling between his home and Guayaquil to attend to the multitude of Norwegians' problems, that he arranged to have Worm-Müller as his assistant.

Seeberg's luck is running out. Previously so accustomed to success, what has happened to bring about this change? Everything is in disarray and one disappointment follows another. A third and final court decision assigns ownership of Isabela to Bruun.

But now the sloop is so worm-eaten below the waterline and so cracked above that she is unsuited for cruising between the islands.

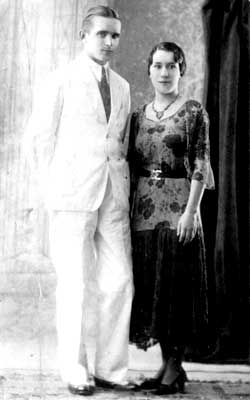

November, 1926. Captain Axel Seeberg (in white suit), with other Norwegians in Guayaquil. Photo courtesy Netta Næs.

Throughout 1928 Seeberg commutes between Guayaquil and Quito, in fruitless discussions with consul Bryhn and other influential people in hopes of raising money. He not only wants to cover his personal debts but also hopes to buy the canning factory at Santa Cruz which is now up for sale. But in vain, it proves to be impossible to raise sufficient capital.

On the night of November 4, 1928, Captain Axel Seeberg, 58 years old, tumbles down a cliff in Quito and is killed. He is buried in the San Diego Cemetery in Quito, 2800 meters above sea level and 8500 kilometers from his children, his wife Helga, and his beloved home in Hvalø.

Santa Cruz

New Year, 1927. Academy Bay at high tide. At the end of the “Ulva” pier stands the tree trunk used as a crane. Leading to the factory is a rail track. The baking oven is hidden behind the factory. The open area is “The Square.” Courtesy Jens Furunes.

For about five months after Ulva first anchored in Academy Bay in August, 1926, there was, generally speaking, unity and excellent cooperation among the colonists. The production of canned food and dried fish continued right into November, 1927, but throughout this period there was an increasing amount of practical problems and internal friction.

The tasks that were accomplished during these fifteen months are quite impressive. From the beginning of construction in August, priority work projects included a quay and the laying of a pipeline from the source of brackish water to the construction site. The spring was located at the inner shore of Pelican Bay; so the installation required all the 400 meters of pipe brought from Norway.

It was the engineer Torstein Eig and the carpenter Henrik Furunes who effectively supervised the building of the factory and the seven small houses, each designed for four people. Borghild Rorud was content to live by herself in a tent with her botanical specimens.

At the end of the pier the men erected a giant tree trunk to serve as a crane. The tree† must have been of an unusual sturdy kind because it continued to stand on the Ulva pier as a silent monument until 1980, serving as a lamp post.

† Locally called “matazarno”—Piscidia cathargenesis.

By means of the crane, fish and turtles were hoisted from the boats, placed on a trolley, and pushed on rails to the factory. When there was a good catch, the factory was busy far into the night with men working in continuous shifts.

Spiny lobsters were caught under rocks at low tide, so most would be found around new and full moon when the ebb tide was at its lowest. In the beginning, catches were enormous, each man returning with 20-30 lobsters after one hour of work. Spiny lobsters lack claws and therefore cannot pinch, but they have a shell studded with stiff pointed spines. A pair of thick gloves was all that was needed for safe catching.

Lobsters could be kept alive in traps for some days, but lisa (mullet) and tortuga (sea turtle) had to be canned as quickly as possible. They also tried to can the large groupers, but the flesh was too coarse and turned an unappetizing color. It was best suited for eating fresh or preserved as “klippfisk”† —the popular salted and sun-dried bacalao.

† Klippfisk is fish originally dried on rocks (“Klippe” means large rock) but has come to mean any type of dried fish. In Norway most of the dried fish is Arctic or coastal cod, but the coalfish, a close relative of the cod, is also used.

Originally the tractor was parked beside the factory and by means of a belt drove an electric dynamo and the large stamping machine, as well as other machinery. It made a terrible noise and used a lot of gasoline. The problem was solved in November when the quietly-running steam engine was acquired from the Floreana colony. There was no lack of wood fuel on Santa Cruz. Now the tractor was freed up for other jobs.

Behind the factory, a large baking oven was built with bricks. Originally, Kristian Stampa was responsible for the important job of baking bread, but he also proved to be an able fisherman and craftsman, and the bread making job was reassigned to others. As with all other cooking responsibilities, baking was not very popular. When on a trip to Guayaquil aboard Isabela, Skaraas and Urholt hired two local cooks. To find someone on San Cristóbal who could cook European-style food was impossible.

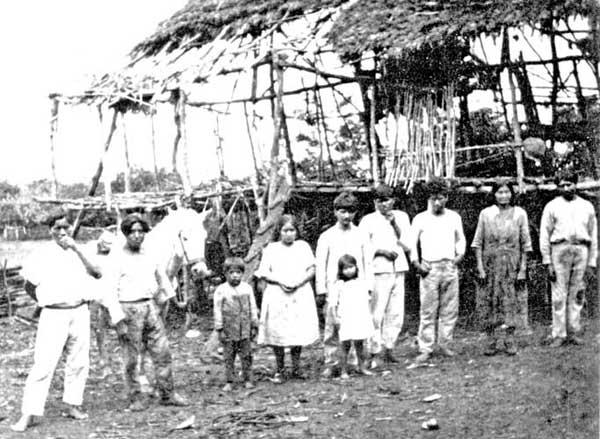

There was great rejoicing when the two cooks arrived in Santa Cruz at the end of May, although Skaraas had to listen to comments on how they should have engaged someone with a lighter skin color: one was as brown as a native American, the other one “as black as pitch.”

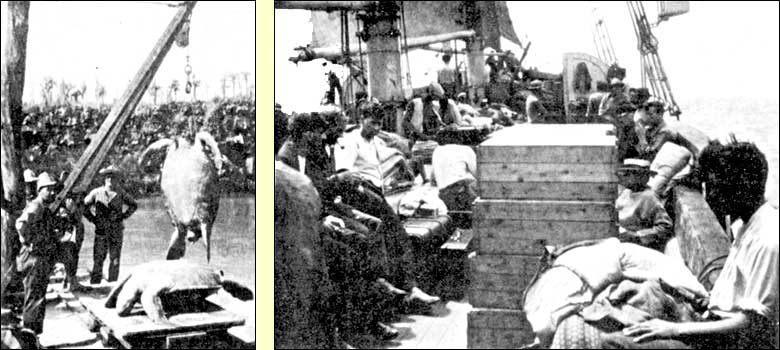

Left: Turtles were hoisted from the boats and pulled to the factory on a trolley. Lars Karterud is standing front left. Photo courtesy Ingeborg Faller Mjelde.

Right: When Ulva sailed to the continent after two months in Academy Bay, the first batch of canned food was ready for sale. Sixteen cases, each containing 96 cans, were sold in Guayaquil. But unfortunately for the colonists, profits equalled expenses. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

Below: Bacalao (dried cod fish) was prepared from large groupers. It brought a good price in mainland Ecuador, especially during the Catholic fast before Easter. At left the youngest member of the expedition, Rolf Halvorsen from Larvik, born in 1910. Photo courtesy Thelma Lea.

Around the factory and the seven small houses, they cleared land and planted. Between the houses were paths edged with lava rocks. A large area was kept clean and level and served as a square and a crocket court. Otherwise the second floor of the factory was the place for meetings and indoor entertainment.

Mathias Breivik had a balloptikon, (epidiascope) a device for projecting drawings and photographs on a white cloth. Such picture-show evenings were popular, provided there was a little energy left. This would mostly be on Sundays and holidays, the ordinary workdays usually left them with too little free time and strength.

As for farming in the highlands, the Norwegians had unexpectedly good luck. From the local workmen, who were left behind by the Ecuadorian of Spanish descent, Baquerizo, they took possession of a well worked plantation at Fortuna (former name of Bellavista). In addition, they also found two long since abandoned and overgrown plantations, called Santa Rosa and Cherla Chacras. At Santa Rosa they harvested crops like yucca and otoy, as well as sugarcane, maize, papaya, plantains (a type of mealy banana used as a vegetable), and ordinary sweet bananas. At Cherla Chacras were oranges and other citrus fruits. However, it took five hours each way on an overgrown path to reach these plantations.

It was gardner Rambech who cultivated and cleared new land at Fortuna. Initially, he received help from the agriculturists Bechmann and Nielsen and later, at the end of January, from the Alatga-man, Sigvart Tuset. Until November, Rambeck and Tuset were the best of work-mates and friends, and pursued a fairly solitary but happy existence in the highlands.

But it was a strenous life. They lived in a small and cracked house left behind by past workers. In spite of frequent rain and a prevailing mist garúa covering the highlands, they suffered from a chronic shortage of drinking water. The situation improved later in the year when they built a mosquito-proof house with a roof of corrugated iron sheeting, off which they collected rainwater.

Rambech became a popular person because of all the goodies he brought down from the highlands. Radishes and beets were grown in record time; turnips, carrots, peas, cucumbers, tomatoes and sweet potatoes took only a little longer. Everyone knew that he tried to grow cabbage for the first Christmas in Galápagos, but how it was going was a well-kept secret. Others would provide the roast veal as they had not managed to obtain the traditional pork; but sauerkraut was absolutely essential if there was to be a proper Christmas. Now it was up to Rambech.

When he came down with a fully-laden donkey the day before Christmas, everbody gathered around him asking about heads of cabbage.

“Why,” said Rambech with a smile, “I think you have enough of them on top of your shoulders!”

Big cheer!

Juleaften (Christmas Eve) 1926. Everyone is in a cheerful mood when Christmas Eve is celebrated in the factory. Isabela has just arrived with parcels, mail and provisions, including tobacco and goodies. Photo courtesy Karen Østmoen.

On Christmas Eve, which is when Norwegians have their main celebration, Skaraas writes:

“Christmas Eve, the 24th, the sloop arrived. We received a lot of provisions and mail. I got six letters and a bundle of newspapers. The boat left immediately in order to arrive at Floreana in the evening.

“We had a really good Norwegian Christmas especially as we now had something to drink and smoke. Neither fir nor pine trees grow here, but we located a nice tree resembling a birch. This was trimmed with decorations that nearly everyone had brought with them, and so we had a beautiful Christmas tree and got into a fine Christmas mood.”

But not only good news came with the mailbag on Isabela.

They also learn that the sale of Ulva is completed and although she is not to be taken over officially by the Ecuadorian Navy before January 10th, 80,000 sucres have already been paid and nearly all of it sent to Norway. They get news relating how the consul operating as agent had collaborated with Trygve Hyenæs in Tønsberg, who is supposed to have asked for kr. 60,000 to cover his own expenses and salary! In short, there was no money left for themselves! How now to obtain provisions, tobacco, gasoline and kerosene, which have to be purchased on the continent?

The shipment of canned goods which went with Ulva and Isabela in October, was quickly sold by Reidar Østern through the agent Eduardo Foppiano. The quality was good and included 16 cases of 96 cans each. But by the time storage expenses and all the agents and middlemen, including Ulva's own representative, were paid, once again there is no money left!

Therefore, during the period between Christmas and New Year's Eve there was a lynching mood in the colony on ”Ulveneset“ Wolf's Point. (Ulva, the name of the ship, is similar to the Norwegian word for wolf, “Ulv.” So they named their settlement Ulveneset,” i.e. “Ulva's Point” or Wolf's Point.) But it is impossible to lay blame at such a distance. New representatives have to be sent to Guayaquil, and as fast as possible, sales and administration must be organized by themselves and certainly not in Tønsberg or by some past Ulva-members. They discuss various solutions like liquidation, immediate dissolution of the company, putting the factory up for sale and then buying it back. They debate back and forth, leaders and representatives are chosen and rejected, and a solidarity statement is signed by the 28 shareholders present. The next shipment of canned goods will be sent to the continent in January. It will consist of 180 cases of 96 cans each, and with this cargo they hope to have a financial surplus. Still more cases are in stock, but these are to be used for trading in San Cristóbal.

After a lengthy crisis session at the factory around New Year 1927, 28 shareholders signed this statement.

“The undersigned hereby declare that they will not in any way take part in efforts to purchase, individually or though agents, but only collectively, in the event that the property of La Colonia de Santa Cruz is offered for sale through liquidation or bankruptcy.

Academy Bay, Santa Cruz

3rd January 1927

Document courtesy Karen Østmoen.

Meetings continue for several days into the new year. Nevertheless, they plan to celebrate New Year's Eve in proper style. Martin Skaraas writes:

“On the 31st, the sloop from Floreana arrived for a visit. Nearly everyone was aboard. There were Seeberg, Bruun, Waardahl, Johanson, Olsen, Hassel, and a local resident. (Engineer Hassel arrived in Galápagos on his own in 1926. Olsen's bacground is unknown.) We walked around the Christmas tree singing. We were all adults, but at Christmastime grownups are children again. We had plenty of excellent sylte (a traditional dish of spiced pork pieces, compressed into a ham-like shape, and served thinly sliced), hot and cold roast, sauerkraut, rice pudding, liquor, beer and wine. There was a large selection of fruit from our own plantation. Bananas, lemons for juice, pineapple, oranges, all harvested ripe from the plants.

“Thorolf Larsen gave the speech to the guests, and Seeberg gave the reply, as well as a vote of thanks for the meal. After midnight the entertainment started since we did not finish feasting earlier. Bruun directed the entertainment. He was exceptionally good, full of incredible stories, jokes, and a lot of card tricks, but then he is from Bergen. [The Bergen inhabitants are jokingly referred to as slightly crazy and special by other Norwegians. They are known for their wit, good humor and local patriotism; always competing with Oslo!] Then there was Johansen who was also good, so the rest of us had to do something, either sing a song or tell a joke. We did not finish before daybreak…”

In late January, all are waiting for Isabela's return. Tension is high at the mention of canning sales. Besides, they are out of tobacco. Thorolf Østmoen describes one of his co-sufferers who is so desperate for tobacco that he is nicknamed “Ashtray.” He even scrapes the pipes that others have put aside, and chews the ash and tar, as if it was chewing tobacco. This greatly irritates other smokers who find their pipes emptied of valuable remains.

“One day there was a joker who wanted to fool him, so he filled the half-smoked pipe with dry donkey manure and placed it in a readily visible spot. Sure enough, it did not escape the sharp eyes of ‘ashtray,’ and before long the contents were placed behind the upper lip. When he had chewed on it he gave a surprised expression and asked what the heck had been in the pipe he was smoking. When he was told he just quietly said, ‘For sure it does not exactly taste good, but having got it in my mouth I'll definitely chew it to the end!‚ ”

The sale of canned food is improving, and after some months of reasonable income the plan to sell the factory is put aside. But more problems arrive. Isabela is confiscated in Guayaquil, and regular transportation is badly missed in spite of some dissatisfaction with Bruun's freight rates and the fact that the cases often got wet.

The problem is alleviated somewhat when Ulva, now re-named Patria, makes a couple of trips to Santa Cruz. They owe this to their man from Porsgrunn, Herman Hansen Vik. He has remained aboard as first engineer and looks good in his uniform, immaculately white, complete with epaulettes, tassels and a sword. In order to continue to work aboard, he had to be enrolled as an officer in the Ecuadorian Navy!

Meanwhile, Alvarado refuses to let the Manuel J. Cobos call regularly at Santa Cruz. Officially because he says the anchorage is unsafe for a schooner with an unreliable engine, but the Norwegians suspect that he is unwilling to freight their bacalao. He has his own men fishing from the schooner, but they are not as skilled in the salting and drying, resulting in a product of poorer quality. Clearly he does not like the competition.

Then a dry period follows in the highlands. Several newly-sown fields fail. The motorboats are also plagued with problems. Either there are leaks due to teredo (shipworms), or there are engine problems. There are times when none of the boats are running, not even the most reliable one named Hope and Doubt. To procure spare parts for the Fredrikstad Motorfabrik engines proves impossible.

Gradually and rather unexpectedly, lobsters and tortuga are harder to find. Even the amount of groupers declines. The Norwegians call the local groupers torsk (cod), but these species are non-migratory, quite unlike the wandering cod of the North Sea. As they fish out one location the fishermen must move to new ones in order catch more. The same is true for the spiny lobsters.

Rumors, slanderous gossip and back biting, especially regarding their various representatives in Guayaquil, become the final straw for the Santa Cruz colony. It is agreed that they will leave in December, sell everything, and divide the profit among those who stayed and worked throughout. Others will only receive amounts to cover their fares home.

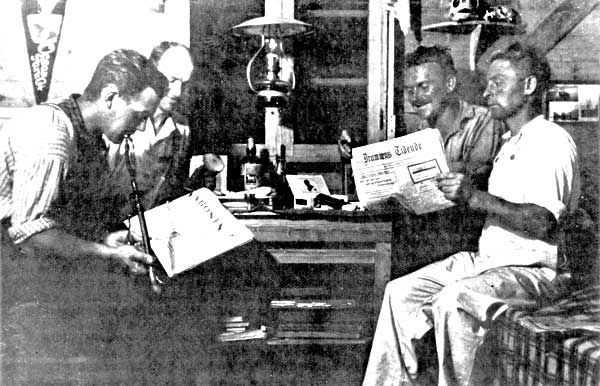

There's nothing like newspapers from home! From left to right are Eivind Erichsen from Halden, M. Th. Nielsen and Thorolf Østmoen from Drammen, and Axel Helgesen from Boda. Photo courtesy Karen Østmoen.

But not all return home.

November 21. Birger Rostrup is soldering cans. This batch of canned food will be among the last as they are running out of sheet metal. A blow torch constructed by Skaraas is used in soldering. Kerosene is connected by a long hose from a pressurized container.

While Rostrup is busy soldering, the coupling between the blow torch and the hose snaps and pressurized kerosine squirts across the floor and all over the man. The liquid on the floor ignites immediately. Without reflection or calling for help, Rostrup starts stamping out the flames with his bare feet. In his fright he forgets about the pail of sand nearby and a large barrel of water just outside the door.

Soon Rostrup himself is on fire. In panic he runs out of the factory like a blazing torch, past the barrel which could have held all of him, rolls around on the ground, but continues to burn. Then he scrambles for the quay and failing to notice the ebb tide, throws himself onto the jagged rocks below. He is badly hurt and is bleeding from several wound when he crawls into the water and finally extinguishes the flames.

He utters not a sound. Andersen and Skaraas are working behind the factory but do not notice Rostrup until he runs for the quay. When they arrive, they help him out of the water and lift him on to the trolley. When they remove what remains of his clothing, large flaps of skin peal off his right leg. There are also burns on his back and left foot. The wounds are cleaned with vegetable oil and they cover him with clean sheets.

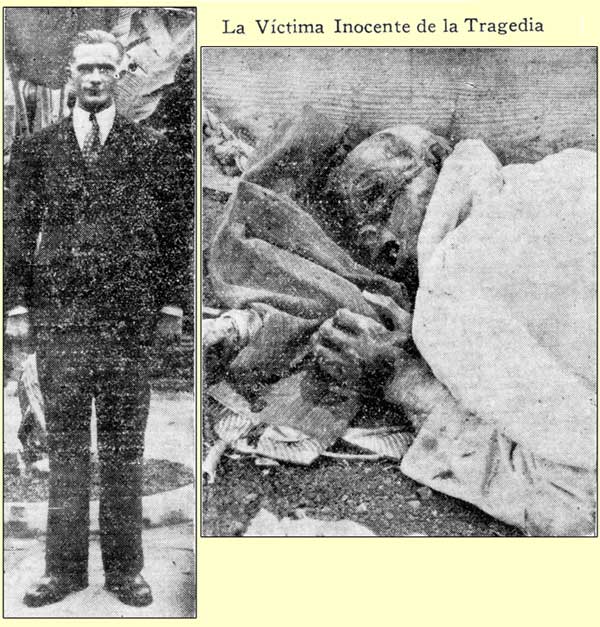

Birger Rostrup from Mandel, who died after a tragic accident in the factory. Photo courtesy Karen Rostrup.

The patient assures everyone that he has no pain, asks for a cigarette, lies smoking and smiling, and is embarassed about all the commotion. Then he is gently carried to his own bed in house number four.

Three days later, Skaraas writes in his diary:

“We stood, the lady and I, at the end of the bed and talked to him. He says, Skaraas, when do you think the boat will arrive? I think I will stay here with the others. He stayed, indeed; half an hour later he was dead. He lay with his big eyes looking at us, and died so quietly that we could neither see nor hear it. But the lady said, now he is dead.”

The lady referred to is Anna Horneman. Together with her husband Jacob Horneman, she has made her way to Santa Cruz on her own and now lives in the highlands at Fortuna near Sigvart Tuset.

Birger Rostrup is buried on November 25, 1927.

On December 22, 1927 Patria leaves with nearly everything and everybody on Santa Cruz. Even old Latri the Mexican, and most of the locals who do not want to stay any longer. Only Elias Sanchez wishes to remain in the highlands as a field hand. The factory and machinery necessary for canning production remain, but the rest of the equipment is loaded aboard ship to be sold on the continent. A last big batch of valuable canned food represents a potentially valuable asset for the markets in Guayaquil.

Remaining now in the highlands of Santa Cruz are Anna and Jacob Horneman and Sigvart Tuset. At the beach are Kristian Stampa, Gordon Wold and Gunnar Larssen. These six celebrate a quiet Christmas at the Horneman's. This time the main dish is lobster.

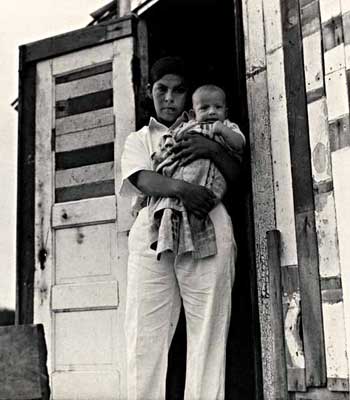

In February 1928, Mrs. Horneman—who is pregnant—leaves for San Cristóbal to live with the Guldberg family while giving birth. When she returns in March, she brings with her a fine baby boy.

Paul Bruun is now skipper on the Manuel J. Cobos, and against the wishes of the owner, he sails to Santa Cruz with mail for the colonists, and takes away fish.

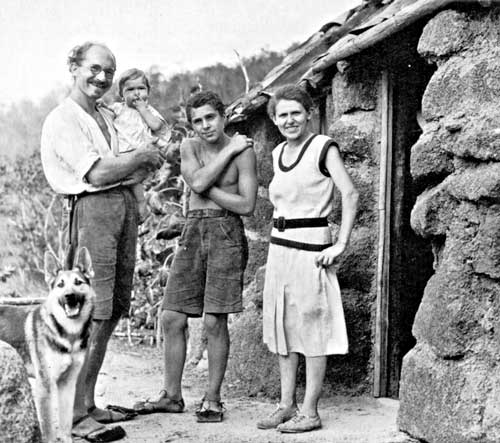

In June, Emil Larsen and Arnulf Greiner come over from San Cristóbal and settle at the beach. They bring along their families as well as a sturdy motorboat made of oak. The Larsens are from Askim, the wife is named Olga and their eight year old daughter, Mary. Eugenie and Arnulf Greiner from Kirkenes have two boys, Per who is three, and Erik born at Campo Noruego, now one year old.

Soon these colonists are like one big family. Tuset cultivates the soil mostly alone, remaining in the highlands two to three weeks at a time. During his free time he frequently visits the Hornemans and receives lessons in both English and Spanish from Jacob. Wold and Stampa each secured fertile land for themselves from the holdings of Rambech and Latris, but they are busy mostly with fishing and capturing lobster and sea turtle. A new source of income is to catch marine iguanas, selling the skin for the manufacture of handbags and shoes.

For a while the belief of the colonists in a Galápagos future is revived. But on October 10 the little community is again stricken with a disaster. Emil Larsen and Gunnar Larssen left the previous day for Tortuga Bay, and have not yet returned. There was a large swell running and they received warnings against the trip, but they left anyway.

In the morning Arnulf Greiner walks over to the bay and finds his best friend Emil Larsen bruised and lifeless. Dead on the beach around him are several tortuga. Greiner shudders when he looks out to sea and observes occasional huge white rolling breakers far out in the bay.

Bahia Tortuga (Turtle Bay) is situated on the southern coast of Santa Cruz. Time and again, treacherous breakers have caught small boats off guard, both inside and outside the entrance to the Bay. At least nine people are known to have lost their lives here. Photo courtesy Thelma Lea.

Nine days pass before they find the body of Gunnar Larssen on the opposite side of the long bay. There he lies beside the boat's broken bow. It is easy to surmise what must have happened. In the boat laden with their catch, they motored out through the breakers and were swamped, causing the engine to stop, and the boat with its passengers and cargo were hurled against the black lava beds below. The boat and contents were quickly smashed.

Left: Emil Sigbørn Larsen was originally with Albemarle and had lived on San Cristóbal for a year and a half before he moved to Santa Cruz with his family. He was 31 years old. Photo courtesy Sverre Winther.

Right: Widower Gunnar Larssen was one of the four from Alatga who finally arrive in Galápagos. Photo courtesy Miriam Brekke.

On October 19, 1928, Tuset writes:

“In the afternoon, we were all gathered down at the beach. It was a modest but touching burial. Molvin Knutsen from San Cristóbal read ‘The Lord's Prayer’ at graveside and sprinkled earth on the coffins. Cobos and the Guldbergs sent flowers. On this occasion speeches were superfluous, and we felt bereaved at the loss of the two comrades.

“For those who lost husband and father we lacked words of consolation.”

The Greiner family, with Olga Larsen and daughter Mary, leave for Norway at the first opportunity.

Emil Larsen from Askim (near Oslo) and Gunnar Larssen from Moss were buried on Friday, October 19, beside Birger Rostrup. At left, Emil Larsen's 8-year old daughter Mary and his wife Olga stand behind the coffin. Photo courtesy Miriam Brekke.

Tuset celebrates another quiet Christmas with the others. Now they have food in abundance: roast pork and sauerkraut, eggs and chicken. But what good is this when human presence is needed?

On the second day of Christmas, the gardener Tuset has the honor of baptizing Horneman's baby, whose name becomes Robert August Horneman.

In February 1929, “Grise Johansen” of the Robinson Crusoe expedition finally arrives at Santa Cruz. He is full of courage and keenness, and even has some cash!

Meanwhile, Tuset receives a letter from his Alatga friend, Harald Skramstad, who writes that Colómbia is the country with a future. Tuset sells his lot of land, and part of the new house at Fortuna to Johansen for 120 sucres. And then he waits for the first opportunity to move on.

Anna Horneman also wants to move. She is again pregnant and does not want to risk another painful delivery in the islands. She wants to return home to Lillesand in southern Norway.

Sigvart Tuset concludes his diary of Galápagos:

“Friday June 7. Cobos arrives at Santa Cruz. Horneman with his family and I left Paradise. We left Santa Cruz on exactly the same day and at the same hour, that three years ago Alatga sailed from Tønsberg…”

Back on Santa Cruz only Gordon Wold, Kristian Stampa, Elias Sanchez and the newcomer, “Grise Johansen,” remain.

San Cristóbal

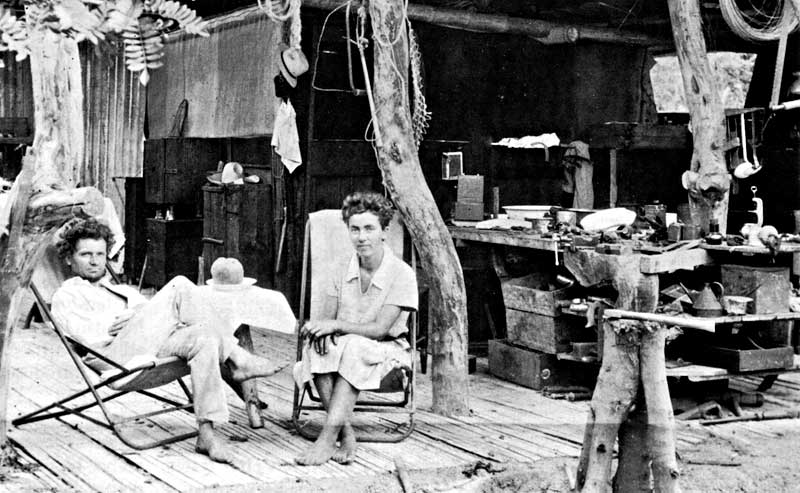

Tired legs are stretched out on an open air porch in Campo Noruego. Content after a long and warm day's work, men and women can enjoy the sunset. From inside one hears domestic sounds, and next door a little one who does not want to sleep is crying. Down in Progreso the crowing of roosters and the barking of a dog can only just be heard—other sounds are carried away with the breeze. Now bend forward, take a sip of coffee, lean back again. The wicker chairs bought in Madeira creak gently with each movement. A basket on the table is filled with tropical fruits. Except for the absence of palms in the foreground, the picture of a South Sea Paradise is perfect. Towards the sunset the sea is shimmering like hammered copper, the Pacific stretching endlessly blue and black to north and south.

Left: Relaxing on the veranda of Worm-Müller's Campo Noruega.

Right: Ruth Ødegård from Oslo on a ride near Progresso. Photos courtesy Robert Ødegård, Tønsberg.

Coconuts are available and before long the palms should also sprout. And near the beach one may have a cottage and a row boat. On Sundays, a ride on horseback up in the highlands to El Junco to enjoy the view and a picnic lunch, or a trip to Wreck Bay to fish and swim.

There is no lack of excitement either. Here one can hunt cattle or wild boar, or take a shovel and look for buried treasure.

In spite of problems in cultivating potatoes and Norwegian vegetables, things really looked promising for the new colonists on San Cristóbal.

What was it, then, that broke up this colony of enthusiastic farmers and fishermen?

Probably the main reason was that originally few of them were indeed farmers and fishermen. They had insufficient practical experience, especially regarding agriculture, and by and large they were only prepared to cultivate “Norwegian” food.