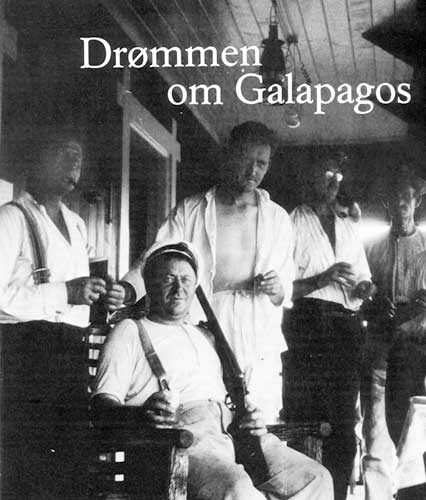

Drømmen om Galapagos

Stein Hoff

This English translation of the Norwegian original was done by Mrs. Friedel Horneman, with subsequent editing by Professor Robert I. Bowman. Except as noted, footnotes are those of the editors. Bold font, bright background in Table of Contents indicates the currently active page.

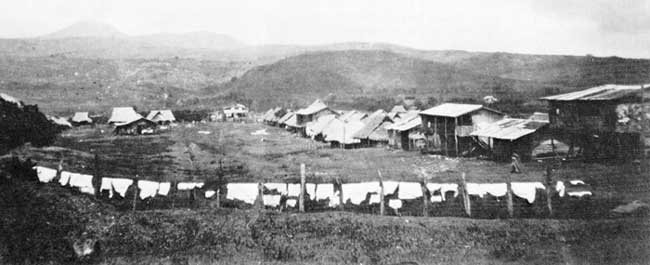

Casa Matriz (Mother House) was the first house built on Floreana by Norwegian settlers.

Photo, taken in December 1925, courtesy of Netta Næss, Larvik.

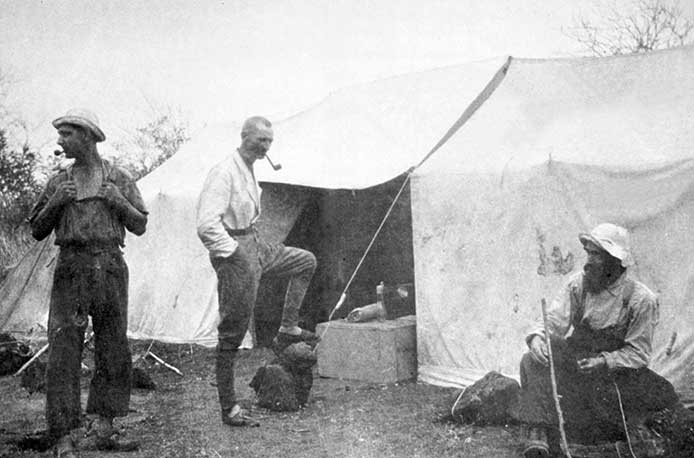

Taxidermist Erling Hansen, zoologist Alf Wollebæk and author John W. Nylander, who lived in a tent on Peninsular Oslo Museum, Floreana 1925, while they studied animals and built the biological station. Hansen and Wollebæk collected many animals and a large amount of scientific data. They demonstrated that the local sea lion is a distinct race and thus later described Zalophus californicus Wollebæki. Photo courtesy of the Whaling Museum, Sandefjord.

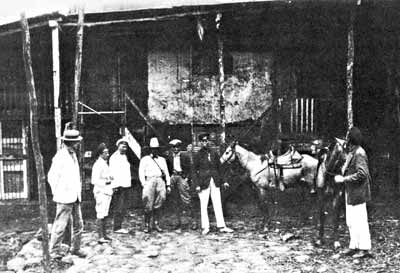

Floreana colonists with freshly-picked oranges, in front of the Pirate Cave, August 1925. Photo courtesy of the Whaling Museum, Sandefjord.

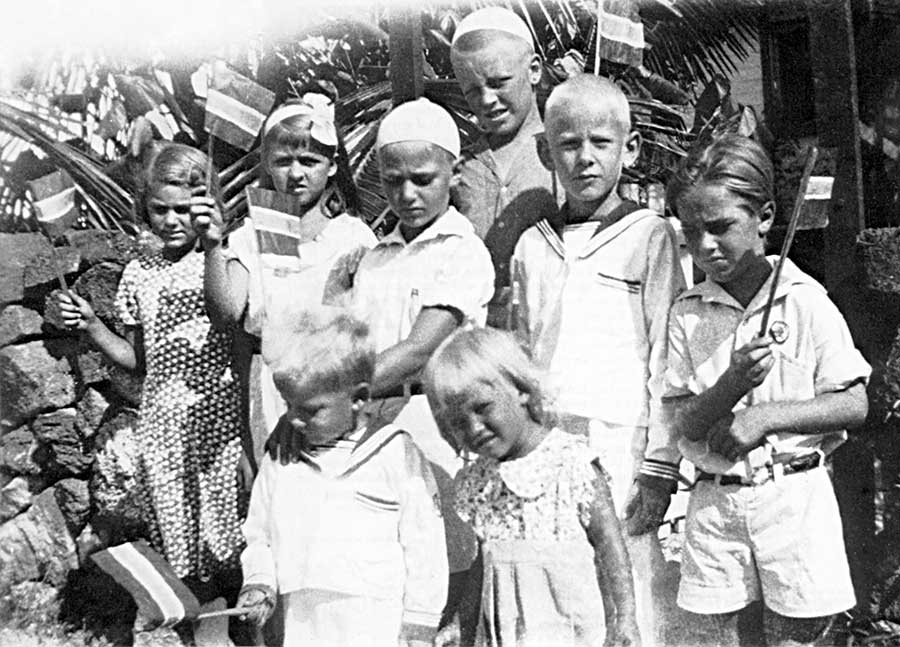

A children's parade on Santa Cruz, May 17, 1938, Norwegian National Day. There was insufficient colored paper to make the entire cross on the flags, so they became somewhat special. Standing in front of Ræder's house, in back row: Carmen Kübler (German), Gloria Lundberg (Swedish), Arne Graffer, Alf Kastdalen, Jacob Lundh and Erling Graffer. In front: Eric Lundh and Anne Stampa.

Foreword: 2014

An amazing number of years have lapsed since 1985 when my life seemed to revolve around Galápagos and anything remotely connecting the archipelago to Norway.

I had known since I was a teenager that fellow Norwegians had tried to settle in these remote and very exotic islands way out there in the Pacific (See the 1985 Foreword). In 1979 my wife and I had sailed to Galápagos with our two children and met many of these transplanted country-men and -women and heard many a strange story. There was no comprehensive work written yet, so in 1984, two years after completing our circumnavigation, I decided to collect all possible information, interview people back home and in the islands, produce a book and make a film about what happened to what once was a grand project of immigration and industry. To do this, as well as a similar project on children in Pitcairn Islands, I took an 18-months break from my work as a medical doctor.

The book (and what became a four-part TV documentary for the Norwegian TV-channel NRK made by photographer Lars Rørholt and myself) sold well, created a lot of interest, and Galápagos old-timer Elfriede “Mutti” Horneman, then a widow and living with her Galápagos-born daughter Friedel in Finnmark in the north of Norway, decided it had to be translated in 1986. (By strange coincidence her husband Jacob Horneman was also born in Finnmark, the most remote county of Norway.) By this time I was back working full-time as a medical doctor and still working on the Pitcairn project, so could not offer much help. But Professor Robert S. Bowman of San Francisco State University had visited the Hornemans and met many of the other Norwegians on several of his visits to Isla Santa Cruz in Galápagos, and supported her idea enthusiastically. He thought he could find an interested publisher. Bowman was a zoologist and an authority on Galápagos crustaceans and had several publications behind him. Fortunately I had the pleasure of eventually meeting him, his wife and his son (who did all the scanning) at his home in San Francisco in September 2001.

Our project suffered an unfortunate set-back when we discovered that the original plates from when the book was printed in Norway were lost. The publisher had merged with another publisher; a lot of original material was discarded or destroyed in the process (apparently due to storage problems) without informing me or other authors! I had returned almost all the photographs to their original owners, so most of the illustrations for the English-American edition were, as mentioned above, scanned by Bowman's son from one of the published books. This caused extra work and a poorer result.

“Mutti” sadly passed away before we could publish her work, Bob Bowman's health and energy was also failing, and publishers were not as enthusiastic about this strange story as the rest of us. When Bowman also passed away in 2006, John Woram volunteered to post the book on his Galapagos.to website. So for many years now John and I have been correcting errors and mistakes and improving the photographic material. Readers of the tables at the end of the book will, however, discover that we have not been able to find out what has eventually happened to everybody mentioned in the book. So if anybody has details or material of relevant interest, please let us know! One beauty of the Internet is that mistakes are easily corrected and relevant links easily inserted.

Being a historical document, with many of the characters being true originals in one of the most exotic places in the world, this book should always find some new enthusiasts out there in cyber-space. And who knows, maybe there might one day also be a paper edition.

Meanwhile, John and I do hope you enjoy this collection of many strange stories, and again my sincere thanks to the initiative of late Elfriede “Mutti” Horneman in Finnmark, to Professor Robert S. Bowman in California, and to the very much alive and active Galápagos- and Darwin-enthusiast John Woram (john@woram.com) in Rockville Centre, New York.

Gullaug, Norway,

Stein G. Hoff (steinghoff@gmail.com)

Foreword: 1985

My dream about Galápagos originated in 1962. At that time I read two books: Such Animals Exist (Slike dyr finnes) by Rolf Blomberg (Swedish) and Rundø—a book about sailing around the world by Erling Brunborg and Carl Emil Petersen (Norwegian).

Both books contained long chapters about the Galápagos Islands and their exotic animal life, and perhaps still stranger, about Norwegians who lived there. In a photograph in Blomberg's book, a fair-haired Norwegian man wanders amidst a landscape of cactus trees and lava boulders. In another, the author's daughter is playing with a grotesque-looking iguana.

The books relate stories not only about accidents, toil and deprivations but also about a fertile highland, about an agreeable tropical climate, about the good feeling of freedom, and about a friendly small community. The two round-the-world sailing adventurers, Brunborg and Peterson were entertained like royalty and enjoyed themselves so much that it was difficult for them to continue their travels westward!

I too wanted to visit Galápagos, preferably in my own boat, like the two aboard Rundø.

Seventeen years later the dream was to become a reality. In 1979, I arrived in Galápagos along with my family aboard the gaff-rigged ketch, Red Admiral. We met the Guldberg sisters on San Cristóbal, and Gordon Wold and the Kastdalen family on Santa Cruz, and learned about the Norwegian expeditions to Galápagos and about hard times and good times—mostly the latter.

We looked at photographs and documents, newspaper clippings and articles, and read a little about Norwegian-Galápagonians in various books. But we found no book describing the full fascinating history of the Norwegian emigration to the islands.

Five years later no one had yet documented the story. Soon, sixty years would have passed since the first one left Norway, so it became an urgent matter to pursue this project.

I decided to give it a try.

This book is like a puzzle, consisting of many separate pieces of information derived from very many sources. Without the extraordinary interest and goodwill of both private individuals and public institutions, it would not have been possible to complete the task. There are many who deserve thanks.

A few of the former colonists are still alive and helped me. To the three on Galápagos, namely Karin and Snefrid Guldberg and Thorvald Kastdalen, must be added Elfriede Horneman of Karpdalen, Kirkenes, Alvhild Stampa and Anne Carmen Mathiesen of Stokke, Karl Johansen of Olderskog, Einar Austlid of Ørsta, Håkon Hellner of Larvik, and Ane Koller of Hamar. Jabob P. Lundh (presently living in Oslo) was only four years old when he arrived at Santa Cruz in 1932. He has been an excellent source of information about Ecuador, Norwegians and natural history in Galápagos.§

§ Karin Guldberg died on 14 January 1996; Snefrid Guldberg 1991; Thorvald Kastdalen, 12 June 1987; Elfriede Horneman, 19 February 1997; Jacob Lundh, 19 March 2012. Others unknown, pending further research

Most of the material about the various expeditions, however, I have obtained from the surviving emigrants, relatives and friends. Netta Næss, and Anne Hesselberg of Larvik, Jacob Worm-Müller of Oslo, Karen Østmoen of Drammen, Siegfried Brunn Johannessen of Bergen, Arne Eilertsen of Oregon, Silvia Randall Andersen of Oslo, Sigmund Tuset of Steinkjer, Knut Wollebæk of Oslo, Knut Høiby of Oslo, the Robert Ødegard family of Tønsberg, Thelma Lea of Stavanger and Arnhild Utheim of Oslo.

I must also thank Vigdis and Peter Stapley, who lived on Santa Cruz for seven years, and now live in Moss. They helped with Spanish translation and literature searches and in making contacts in Galápagos.

Gayle Davis on Santa Cruz searched for relevant literature in the library of the Darwin Research Station and referenced or copied material of possible interest.

The Angermeyers in Santa Cruz, especially Carmen (née Kübler) and Karl, were valuable sources of information about the Norwegians they knew so well.

Dr. John Garth of Los Angeles, zoologist with the Hancock expeditions of the 1930's, has been an enormous help by making available his personal photographs and journal notes and facilitating contact with the Allan Hancock Foundation, University of Southern California.

Carl Emil Petersen and Trond Tommelstad have lent me their large collection of slides from Galápagos.

Erling Brunborg, who for many years collected material for a book, gave me all his notes and photographs.

Kristian Hosar of Lillehammer also turned over to me all the information he collected from articles appearing in the Gudbrandsdølen & Lillehammer Spectator about the wandering valley dwellers (døler).

Torkel Fagerli of Sandefjord, spent much time digging into public archives and the libraries in Sandefjord, Bergen and Oslo for old newspaper articles and information about people.

Arve Torkelsen at Grøndahl & Søn publishers has been an inspiring coach.

Finally, dear Diana, who believed that I might have more free time as an author, but ended up canceling our vacation for 1985; I will make up for it at another time. Thank you for your patience and inspiration.

Kristiansand, September 1985

STEIN HOFF

The currents and not the marine iguanas are the real witches of the Enchanted Islands. Photo courtesy of the Allan Hancock Foundation, Los Angeles.

Part I

Shipwreck of the Bark Alexandra

May 1907

The bark Alexandra from Kristiania § has drifted for three months—three endless long months of calm and inactivity. Never has Captain Emil Petersen from Mandal or the 19 other men aboard experienced anything like this. For sure, not many of them have much sailing experience. Petersen himself has plowed the same route across the Pacific for six years, but a fair number of the crew are young people. In recent years it has been considerably more difficult to enlist an experienced crew. Alexandra is made of steel, thus slightly modern but still a pure sailing ship, a three-masted barque. But with few exceptions, Norwegian sailors prefer working aboard modern steamers.

§ The oldest name for the Norwegian capital was Oslo, but in the 1300s it was changed to Christiania. In the 1800s the spelling was changed to Kristiania and then back to Oslo in 1925.

Petersen would turn bitter when he recalled how most of his best sailors left him and signed on with the noisy smoke-spewing competitors.

Emil Petersen from Mandal was skipper of the Alexandra from 1902 to 1907. Photo courtesy Gudrun & Ruth Ordrop.

Emil Petersen from Mandal was skipper of the Alexandra from 1902 to 1907. Photo courtesy Gudrun & Ruth Ordrop.He shields his eyes from the stinging sun, which is now right over the top of the mast. Everywhere there are blue skies with scarcely a cloud to be seen. Soon it is half-past twelve. The horizon lies hazy and fuzzy in the muggy heat. Nonetheless he takes the sun's elevation with his sextant and confirms his worst fear: they have drifted far to the northwest during the past 24 hours and are 20 nautical miles farther away from Ecuador and the South American coast. Imagine, they had this coast in sight more than three months ago!

The sails and pennants hang lifeless. Only now and then do they stir when a swell causes a little movement of the ship. The rigging creaks sorrowfully, accurately reflecting Petersen's own feelings.

Only God knows how often the skipper recalls the fateful delay at Newcastle, Australia. And the cause was simply that he could not round up a crew as quickly as on previous occasions when he prepared for the same sailing trip to Panamá.

Consequently, they remained in port nearly one month too long. Although it was over a year ago that the ship put into dock for scraping and caulking, the hull was not in too bad shape before the delay at Newcastle. But on the first day at sea Petersen realized that the ship's bottom was encrusted. Even with a good breeze it was impossible to exceed a speed of more than 7½ knots.

Anyway, in the roaring forties the ship progressed eastward toward South America. In a storm east of New Zealand, one of Alexandra's sails blew out because the crew was tardy in making it secure; but otherwise the sailing had gone smoothly and safely on the correct course all the time. There were some minor disciplinary problems but none so severe that the officers could not quickly restore peace and quiet. And now, after 163 days at sea, the hull is so overgrown with seaweed and goose-necked barnacles that below the waterline Alexandra resembles an intertidal rock more than a ship. The stern is especially bad. Petersen can see it when the ship rolls and a four to five inch long “beard” smacks the surface of the water. The vessel seems to be firmly attached to the sea! Without a favorable breeze, the Humboldt Current is the absolute ruler. Daily it pushes Alexandra 20 nautical miles or more in the wrong direction.

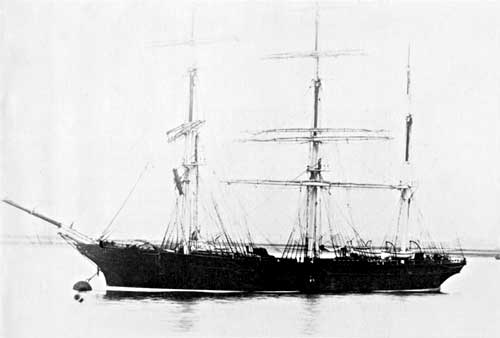

The steel-hulled barque Alexandra was built in Aberdeen in 1874 as a wool-clipper. During her last five years she transported coal from Australia to Panamá. Photo courtesy Norwegian Maritime Museum.

The mood aboard ship is not good. A couple of weeks after they were driven away from the enticing coastline, there was a mutinous state among the sailors. Part of the crew demanded one of the lifeboats so they might row ashore. It did not help to discourage them by explaining that what they intended to do was suicidal; that nobody could successfully row 400-500 nautical miles against the current. In fact, Petersen had to take out his revolver in order to bring the men to their senses.

But soon even Petersen's loyalty to the shipping line of Johanson & Co. at Kristiania begins to weaken. Soon life will be endangered whether or not one stays aboard. To literally sail into starvation is not a pleasant prospect.

From calculations made on the 7th of May, 1907, Petersen knows that the Galápagos Islands are just beyond the horizon. He keeps a lookout to the north but the haze limits visibility to barely 15 nautical miles. In every direction he has the same disheartening, unbroken panorama of sea and sky, sky and sea.

The same morning the steward, Gabriel Abrahamsen—who like the captain is from Mandal—tells him privately that there remain less than 100 liters (26 gallons) of drinking water. Confound it! Petersen looks at the glittering surface of the sea. Never has he used more than 70 days on this stretch. Being a conscientious person, he had ordered double rations of water and provisions to be put aboard. But who would have thought that Alexandra would drift for months like a phantom ship?

Normally, visibility at sea is best in the early morning. Captain Petersen is not surprised when at five thirty the next morning he sees the profiles of several islands to the north.

He has already discussed the matter with his second mate, the Scotsman Morrison. He also informs the cook Abrahamsen that he is thinking of abandoning the ship. Together they bring all the remaining water and provisions on deck in the shade of an awning. There is a short meeting with the crew. The officers explain the situation, point to the outlines of land, explaining that these are the Galápagos Islands, and read aloud what is written about the islands in the manual South America Pilot.

It became more and more difficult to call the crew to order. Several times the captain had to threaten them with a revolver when orders were not obeyed. Sketch by Jacob Sømme from The Crew of the Barque Alexandra.

It became more and more difficult to call the crew to order. Several times the captain had to threaten them with a revolver when orders were not obeyed. Sketch by Jacob Sømme from The Crew of the Barque Alexandra.The crew is informed that from earlier times the islands were well known to pirates and whalers. The old Spaniards gave the islands the nickname Las Islas Encantadas—the enchanted islands—because of the currents which gave the impression that the islands kept moving. The manual also states that there are fish and tortoises in abundance. Some islands have fruit trees remaining on abandoned plantations, and in the highlands of these islands may be found sources of fresh water. Such an island is the one that is nearest, Floreana, 35 nautical miles east-northeast. The only island with permanent inhabitants is San Cristóbal, still farther to the northeast. In actual fact, there was at this time a settlement on Isabela too.

Now that the captain has resigned, the crew hesitates no longer. All of them decide to row to Floreana, obtain provisions and then continue to San Cristóbal.

The pile of provisions on deck is pitifully small. It is divided into two portions, one portion stowed aboard each of the two lifeboats together with 20 liters of water. Nine men follow the first mate in one boat, the remaining nine follow the captain into the other. All the Norwegians are in the latter boat. In addition to Petersen they are Abrahamsen the steward, both from Mandel, another steward and the ship's carpenter Herman Karlsen, both from Botne in Vestfold.

Before they abandon Alexandra, they write a message in several languages, explaining the circumstances, and nail it to the deck. Then they hoist the Norwegian flag on the mizzen mast and light the lanterns. After this they leave Alexandra to herself. The vessel is in good shape and with a full cargo of 2300 tons of coal aboard.

The rowboat with the first mate manages to reach Floreana in three days. The seamen procure food and water and continue on to the inhabited island of San Cristóbal where they arrive in good shape on May 19th. From San Cristóbal they obtain passage to Guayaquil on the Ecuadorian mainland with the schooner Manuel J. Cobos. At the Norwegian consulate they file an official report. The first mate explains that the two boats kept together for two days and nights before they lost sight of each other. His guess is that the captain's boat drifted off and landed on Isabela or Santa Cruz.

An Ecuadorian naval ship is sent to the Galápagos to look for the missing sailors. Near Iguana Cove at the southwest point of Isabela, they find the Alexandra wrecked and broken in two. But the afterdeck of the ship is still dry and standing upright on its keel, the Norwegian flag waving defiantly in the breeze. They find no other sign of humans, and when the naval vessel returns to the continent, the ten missing sailors are declared perished.

Hans Erichsen was the cousin of Emil Petersen and also was from Mandal. He chartered the schooner Isadora Jacinta to search for survivors from the Alexandra. Photo courtesy Gudrun & Ruth Ordrup.

Hans Erichsen was the cousin of Emil Petersen and also was from Mandal. He chartered the schooner Isadora Jacinta to search for survivors from the Alexandra. Photo courtesy Gudrun & Ruth Ordrup.But at home in Mandal, Petersen's relatives fear that the search was not thorough enough. Another person from Mandal, Hans Erichsen in Chile, becomes involved in the matter. He has prospered so handsomely through the country's saltpeter mines that he can afford to charter the small schooner Isadora Jacinta to undertake a more thorough search. The skipper is a German named Bohnhoff. He knows the island localities, and his schooner is easy to maneuver in shallow waters.

Bohnhoff and his Isadora Jacinta do a thorough job. After searching three other islands, the schooner arrives at Santa Cruz where eight of the ten shipwrecked sailors are found alive.

By now, the men from Alexandra have suffered half a year of the most uncomfortable Robinson Crusoe existence. The two who died are young Fred Jeff from the USA and a German, Martin Schaeffer. The eight survivors are in wretched condition and cannot get away from the island fast enough. While they eat and drink to regain strength, they describe their sufferings under the equatorial sun.

On the third night, when they lost contact with the other boat, they drifted off course, going too far north. At dawn, when they realized their situation, they first tried to row against the current in an effort to reach Floreana as planned.

For several days they persisted before giving up and then headed for Santa Cruz instead. On the twelfth day they reached shore. They managed to land their boat on a small beach between black fissured lava rocks, but were so weak that they could barely crawl around in a desperate search for something to drink. No one had strength enough to drag the boat higher up the beach.

When they returned after drinking dirty rainwater found amidst the thorn scrub, it was too late. The high tide had moved the boat. It was already wrecked, and practically all their fishing gear, guns, and other equipment was destroyed or lost. Six months of indescribable misery will follow.

“A ship! A ship!” The Isadora Jacinta finds the survivors after six months. Sketch by Jacob Sømme from The Crew of the Barque Alexandra.

“A ship! A ship!” The Isadora Jacinta finds the survivors after six months. Sketch by Jacob Sømme from The Crew of the Barque Alexandra.They make the mistake of remaining in the cactus-studded coastal region of the island. Here they will never find fresh water or the fruits that grow in the interior of the island. For the most part they live on marine turtles, which they kill when the animals crawl up on the beach after sunset.

During the first days ashore, the Captain carries Alexandra's gold in a money belt around his waist; but this proves too heavy and uncomfortable. Some days later he decides to bury the gold—valued at 600 pounds Sterling—on one of the beaches. Several of the crew are present as witnesses so as to be sure they can locate the hiding place at a later time.

When Isadora Jacinta picked up the bearded and emaciated crew, nobody remembered to retrieve the money belt. It was only in Guayaquil ten days later that one of the crew suddenly jumped up from his chair screaming, “The Gold! The Gold!” As far as is known, the gold still rests in peace out of reach of Norwegians and countless others who have later tried to locate Petersen's money belt.

Thus Norwegians made their first sacrifice to the ancient Galápagos dieties. It would not be their last.

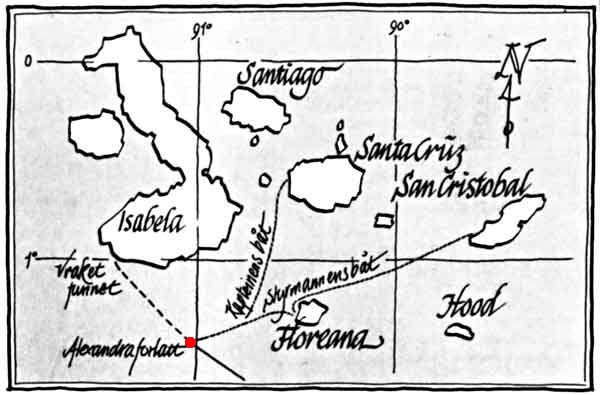

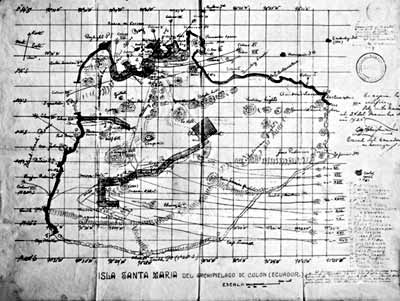

The map shows where the Alexandra was abandoned (red dot) and the path of the two rowboats to two islands. Because of the strong currents, the captain's boat drifted north and was later shipwrecked on Santa Cruz. The first mate's boat arrived at the settlement on San Cristábal without loss of life.

The Galápagos Dream

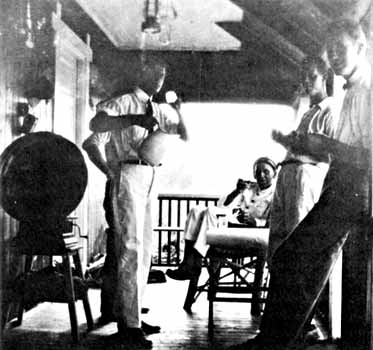

A relaxed Christmas atmosphere on the porch of Casa Matriz, Floreana, 1925. Photo courtesy Netta Næss.

Olaf Eilertsen, Aug. F. and La Compania de Floreana

Emil Petersen, the captain of Alexandra, is tired of the sea. He stays ashore and prefers not to talk about his adventures in Galápagos. It doesn't help matters that the newspapers are full of reports about Alexandra's strange voyage or that he is celebrated as a hero on returning home. From his point of view there's little to be proud of, having left his ship valued at 30,000 pounds Sterling (which Lloyds replaced while pointing out the disgrace of abandoning a ship in perfect condition). It is also humiliating to think that Alexandra drifted ashore only 30 nautical miles from Port Villamil, Isabela, where they might have obtained help to rescue her and save themselves. In addition, he forgot the ship's gold, buried on a Galápagos beach. But worst of all is the nagging responsibility he feels for the two sailors who perished.

The other Norwegians from Alexandra do not grieve so badly. Gabriel Abrahamsen and Herman Karlsen like to talk about their adventures at sea. Karlsen's favorite topic of conversation is the half-year that he was shipwrecked. And the gold that he also forgot, as well as many other stories about buried treasures, make listeners' eyes sparkle. About the same time that Karlsen and his companions struggled to survive on Santa Cruz, a buried pirate treasure was actually found on Genovesa, one of the other islands of the Galápagos.

Olaf Eilertsen was an experienced skipper from Larvik. In 1911 he met Herman Karlsen, the carpenter from the Alexandra, and began dreaming about expeditions to Galápagos. Photo courtesy Arne Eilertsen.

Olaf Eilertsen was an experienced skipper from Larvik. In 1911 he met Herman Karlsen, the carpenter from the Alexandra, and began dreaming about expeditions to Galápagos. Photo courtesy Arne Eilertsen.Soon enough, danger and hardship fade into the background, replaced by memories of excitement and exotic nature. Santa Cruz becomes a dream island. Did not Captain Bohnhoff relate that the highlands were so fertile that one could almost see bananas and papayas shooting out of the red-brown soil? And did not the giant tortoises reach a weight of over 300 kilos (about 660 pounds)—like wandering tin cans with the finest contents imaginable!

As the years pass, stories about Galápagos become more and more colorful. And when Herman Karlsen signs on as carpenter aboard Fiery Cross before the first World War, skipper Olaf Eilertsen becomes one of his keenest listeners. Eilertsen, who was 28 years old when the news about Alexandra spread throughout the country, is fascinated by the report. He begins to collect charts and literature about this island group.

In the autumn of 1924, Eilertsen is a central figure in a group of restless and adventurous men who meet in Larvik. The seven or eight friends agree that their opportunities in the Old Country are rather limited. One must go abroad! But now it is not so easy to immigrate to the United States. Of course, Canada is an alternative, but if one were to leave Norway, shouldn't one try to go to a place with a milder climate?

Olaf Eilertsen always carried his charts and stories to these meetings. And late at night, with tobacco smoke thick beneath the ceiling, and glasses of ale leaving new stains on the Galápagos charts, they daydream. The charts were already cluttered with pencilled notes and small sketches, and judging from these there were more treasures than sand on the beaches of Galápagos!

Eilertsen has other sources of information than Herman Karlsen's stories. He knows the very same Aug. F. Christensen of Sandefjord (Eilertsen's cousin Signe was married to Christensen), Ecuador's consul in Norway, and the man behind a series of newspaper articles about the fantastic Galápagos Islands.

“Aug. F.”

August F. Christensen—or “Aug. F.” as he is known among friends—is the son of Norwegian whaling pioneer Christen Christensen. In 1905 at the age of 17, Aug. F. was aboard his father's Steamship Admiralen when this, the world's first modern whale-factory ship headed for the Antarctic. From 1907 to 1914 he was head of whaling operations on South Shetland Island and in Chile. While in Chile he spent time travelling and studying the coast of several countries in South America, and taught himself Spanish and English.

Aug. F. had scientific interests too, participated in research, produced charts and published articles. Gradually he became more and more interested in the populations of whales along the coast of Ecuador and around Galápagos. On his way home to Norway in 1914 he was interviewed by the newspaper Nordisk Tidende in New York, and on Thursday February 26, one could read on the front page that the young (he was now 26 years old) whaling chief had been granted whaling concessions in Perú and Ecuador. Moreover, he obtained permission to “allow a Norwegian company, under the Ecuadorian flag, to use the island of Floreana in Galápagos.”

Aug. F. Christensen had an early interest in whaling possibilities and the exploitation of natural resources in Galápagos. From 1918, he was Ecuador's Consul in Norway. Photo courtesy Knut Høiby.

Later the same year, a series of articles by Aug. F. Christensen about the Galápagos Islands appear in Norwegian newspapers. However, an expedition to the archipelago would not materialize for many more years. The reason might have been the same as 30 years earlier, when plans about northern emigration to Galápagos were “put on hold.” It was in the 1880s that a company was formed in Ecuador for the purpose of inviting emigrants from Switzerland and Scandinavia to settle in Galápagos. At that time it was feared that the USA or some other great power might annex the strategically-situated but sparsely-populated islands. In 1886, Adolfo Beck—one of the men who initiated the forming of “La Compania Colonizadora Suizo-Escandinavia”—presented to the Ecuadorian Government a list of names of those who wanted to travel. (“Distinguished, hard working sailors and fishermen excellently qualified to colonize the islands.”) He also indicated that more information could be expected to follow.

But the government in Quito required that all who colonized Galápagos should immediately become Ecuadorian citizens. Beck could not accept these terms and the plan was never implemented. If Aug. F. Christensen received the same information in 1914, it may explain why nothing more was heard of his plans until nine years later.

By 1923 Christensen has been living back in Norway for several years. He has followed family tradition of becoming a shipowner and a Consul. Serving as Ecuadorian Consul from 1918, he had an excellent opportunity to reactivate his colonization plans. Finally he reached an agreement which gave 20 hectares of land to each Norwegian who might colonize Galápagos, and exemption from taxes for the first ten years. Moreover, they would be permitted to retain their Norwegian citizenship. Christensen and his group also obtained the rights to all hunting, fishing and trapping on the uninhabited islands which Norwegians might colonize!

In February 1923, he was able to invite all “honorable Norwegians” to settle on these “islands of opportunities.” But it was not until one and a half years later, when Olaf Eilertsen tells him about the burning interest in Galápagos among his companions at home in Larvik that something is about to happen.

Aug. F. and his influential brother Lars propose the founding of a joint stock company, which would organize and finance a Norwegian colonization attempt in Galápagos. The company will be named La Compania de Floreana.

Kristiania Journalists on Floreana

Nowhere in his many articles about Galápagos during the years 1914 to 1925 does Aug. F. Christensen write about himself visiting the islands. Normally one would have expected references to times and places if he had been ashore; therefore one may conclude that until August 1925 Christensen never set foot upon the black lava shores—not even on Floreana with which he was so preoccupied. If this assumption is correct, none of the leaders or other members of the 1925 and 1926 expeditions had any personal experience with the islands. They must have been inspired through second- and third-hand sources of information.

Without counting the three men from the Alexandra, we only know for certain that three other Norwegians had spent more than a few hours ashore prior to 1925: they are the Kristiania journalists Finn Støren, Per Bang, and Bang's good friend Jens Aschehoug.

Sailing on the Cæsar was an adventure in South American folklore. The deck was crowded with passengers, fishermen, fishing equipment and provisions. Pigs and dogs moved about freely. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

Sailing on the Cæsar was an adventure in South American folklore. The deck was crowded with passengers, fishermen, fishing equipment and provisions. Pigs and dogs moved about freely. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.In December 1921, the three arrived via Panamá in Guayaquil, Ecudaor's main seaport. Here they temporarily separated. Støren remained on the continent while the other two travelled the 600 miles west to Galápagos aboard the Cæsar, a 40-ton, two-masted schooner. On the main island of San Cristóbal they were to meet the governor and arrange permission to stay. They intended to remain a few months on uninhabited Floreana. As it turned out, the island's head man was away, but in his place they got to know the 24-year old Manuel Augusto Cobos.

After the infested tropical slum quarters of the Port of Guayaquil, where they rarely met anyone who spoke anything but Spanish, the two men were happily surprised to meet such a fine, well-educated gentleman. He spoke French and English fluently, rode about dressed impeccably in a white suit, and lived in lofty style surrounded by servants and a number of beautiful young women. And most remarkable of all, he seemed uninterested in bribes or payment.

Señor Cobos was hospitality itself, and the Norwegians were promptly invited to be guests in his home for some days.

The transition from Cæsar, where the deck was crowded with provisions, passengers, domestic animals and dogs, to Cobos' spacious hacienda, was unexpected and pleasant. Here in the village of Progreso, three hundred meters above sea-level, the air was fresh compared to the sweltering heat of the coast.

The village of Progreso is 300 meters above sea-level on Isla San Cristóbal. In the mid-1920s it had about 300 inhabitants. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

After an excellent dinner their host escorted Bang and Aschehoug to the south-facing shaded veranda. A barefoot servant followed, helped each guest to find a comfortable seat, and saw to it that nothing was lacking. Satisfied and happy, the two sat and conversed with their amiable host. Cigars were lit, and while the two from Norway sipped an excellent French cognac and admired the stars through the mosquito netting, Don Manuel told of his father's life and fate. But first they got a resumé of island history.

Pirates and Whalers

The first European to arrive at the Galápagos Islands was Fray Tomás de Berlanga, Bishop of Panamá. In a calm, he drifted away from the coast with his caravel and by chance arrived at the island group in 1535. Desperately in search of drinking water, he went ashore on several islands, and later on described the strange animals and the dry cactus country that he found there.

During the next 300 years the islands continued to be a no-man's land, visited mainly by pirates and whalers. There were los Galápagos, the giant tortoises which made the islands especially attractive to seamen. It was as if they were specially designed for the dark deep holds beneath the decks of sailing ships. Here they were stacked as ballast. To the sailors' astonishment and delight they lived up to a year without light, food or water before they landed in the soup pots. An estimated 200,000 Galápagos were hauled away in this barbarous way. And so the tortoises gave the name “Galápagos” to the island group.§

§ “Galápago” is a Spanish name for tortoise or a mantlet or great wooden shield covered with hides to protect an assailant from the bullets of sharpshooters. (Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia vol. III, p. 2432.)

Except for this, the naming of individual islands was marked by disagreement and confusion. Each island had at least two names assigned to it, one English and one Spanish. With few exceptions, the Spanish names are now the official ones. Bishop Tomás himself never proposed names, but during the following decades Las Islas Encantadas was used. The name “Enchanted Islands” derives from the fact that ocean currents often played—and still do play—tricks on seafarers: the islands seem to be moving around, luring ships to reefs and rocky islands, as if directed by evil forces.

Until 1832 nobody lived on the islands for any length of time, apart from shipwrecked sailors and an alcoholic Irishman named Patrick Watkins. In 1807 he deserted a ship which was anchored at Post Office Bay to capture tortoises and leave mail. The famous barrel at Post Office Bay is probably the world's oldest “post office.” It is still there after more than 200 years. The barrel itself is replaced periodically as it deteriorates, but the system is timeless: mariners and others passing by forward mail to each other.

For three years and possibly longer, the red-haired Patrick lived in a shelter on Floreana. He cultivated a few vegetables, which he sold to visiting ships in exchange for liquor. It is reported that potential customers often had to search amidst the grass and bushes to find the helpless drunk. He could not, however, have been completely lacking in initiative because he soon tired of his loneliness. One day he stole a rowboat and some weapons, kidnapped three sailors and forced them to sail with him to the Ecuadorian mainland. When the boat finally arrived, the Irishman was the only one aboard. Authorities in Guayaquil, who believed that he had killed and eaten the others, threw him into prison where he spent the rest of his life. Nevertheless, Patrick is regarded as the first human colonist on Galápagos.

In 1832, ten years had passed since Ecuador declared independence from Spain. General José Villamil visited the islands and feared that a foreign nation might be tempted to annex them. Since they were situated due west of Ecuador, he thought it logical that they should become part of the new republic. Lacking a navy, an army colonel was sent to take charge of official matters. In a ceremony on February 12, 1832 at Post Office Bay in the presence of some whalers and a handful of soldiers, the whole island group was annexed. Shortly thereafter a small colony was established on the island with General José Villamil himself as head man.§

§ February 12, an official holiday, is now known as Galápagos Day. Coincidently, Charles Darwin was born on this date in 1809!

Three years later, when Charles Darwin visited the islands during the famous voyage of the Beagle around the world, he found a well organized colony of about 250 inhabitants.

However, problems arose when the government in Quito expelled pardoned prisoners to Floreana. The colony soon broke up because of internal conflicts. This situation was later repeated in a new colonization experiment with prisoners. Over a period of some ten years, two governors were killed and a third forced to flee, while the tortoises were hunted to extinction on the island. After one of the periodic drought years, some colonists established themselves on San Cristóbal but most returned to the continent. Floreana was once more left to the sea lions, iguanas and birds.

A group of islands, spread over 80,000 square kilometers (50,000 square miles) and nearly uninhabited, is difficult to administer. When Ecuador elected a president with a religious preoccupation, he wanted to resume colonization and, at the same time, abolish prostitution in the country. He thought he had found the ideal solution to both problems when he shipped 300 prostitutes all at once to Floreana. The women received soap, cooking utensils and a few other items, but they had to arrange food and housing for themselves. Men were not to live on the island.

Since Floreana's tortoises were exterminated, whalers did not stop there as frequently as in former years. But an island exclusively inhabited by 300 easy-going women could not be resisted by sailors! It was not long before all the prostitutes had returned to the South American mainland aboard various ships. Until the government in Quito was overthrown, they stayed south of the Ecuadorian border in Perú.

Manuel J. Cobos

In 1869, Manuel Julian Cobos, a man of Spanish descent and father of Manuel Augusto, became interested in San Cristóbal Island. The elder Cobos had great influence both in business and politics. He managed to get mainland prisoners assigned to him, employing them as forced laborers on San Cristóbal.

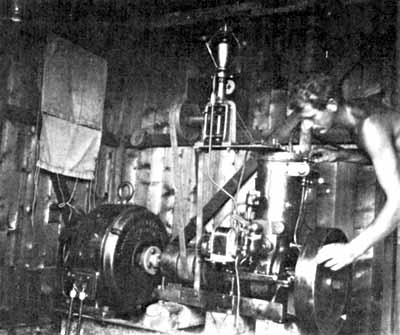

Within a short time he had constructed a seven kilometer-long road from the southeast shore of the main bay up into the fertile highlands. Here he founded a village with 200-300 inhabitants. The community was given the benevolent name of “Progreso” and his house “Hacienda Progreso.” After several years of hectic construction activity, the sugarcane and coffee plantations yielded a good harvest. A modern steam-powered sugar factory was built. At the factory there was also a steam-driven generator, and electric lights were installed. Down at the bay, later known as Wreck Bay because of the conspicuous shipwreck in the middle of the entrance, a small wharf with rail tracks was constructed. Here the governor's house and the island's only lighthouse were also located. With the help of a German engineer, pipes were laid from the crater lake, “El Junco,” in the highlands, to Progreso and down to the wharf. In South America around the turn of the century, interior electric lights and piped water were real luxuries. Progreso lived up to its name during these early years.

The schooner Manuel J. Cobos, named after Progreso's founder, moored along the jetty in Wreck Bay. Photo courtesy Arne Falk-Rønne.

The schooner, which linked the islands with the continent, was the lifeline of the community and was named after the head man himself. It took care of transporting the island's products eastward to Guayaquil, and the principal provisions back west to the growing island community.

The prisoners on San Cristóbal worked like slaves without salary. The demands of the head man and his supervisors were often inhumane, with punishment for laziness and disobedience ranging from flogging and solitary confinement to exile on one of the a desolate islands or even execution. Don Manuel did not hesitate to personally perform the punishments.

“My father's methods showed that our family descends from Spain!—… the Spanish inquisition I am referring to,” the junior Manuel commented dryly. Bang stared at him, but the tropical night made it impossible to detect any facial expression. The host continued to relate how his father's ruthlessness finally led to an uprising, as gradually he started to demand as much from regular employees as from ex-prisoners. On the first bloody rebellion he was hurt, retreated, and some days later took cruel revenge. But in 1904 his days were numbered. One of his formerly faithful foremen, Colombian Elias Puertes, could no longer tolerate his dictatorial methods. In a final revolt he stole Cobos' revolver, and from close quarters shot three bullets into his superior's face and abdomen. It is incredible that Cobos managed to escape through a bedroom window on the first floor, and crawled away to hide in the bushes, but he was soon found by his enraged employees who hacked him to death with machetes.

“The bedroom in which my father lived is located directly behind us,” Cobos Jr. said. Even though comfortably seated in easy chairs, with the taste of excellent cognac against their palates, a shiver ran down the spines of Bang and Aschehoug. They stared at their host. They noticed the revolver that Cobos carried in his belt since they first met him down at the harbor. Why had he not taken it off?

Left: When Jens Aschehoug and Per Bang visited Galápagos in 1922, the steam-powered sugar factory was in full operation, but decay had set in. Photo courtesy Sylvia Randall Andersen.

Right: Rogerio Alvarado was married to Josefina, Manuel Cobos' older sister. He lived most of the time in Guayaquil. Photo courtesy Robert Ødegård.

“I was only six years old when my father was killed,” continued Cobos. “I lived on the continent and hardly had any contact with him. I remember him only vaguely. My sister Josephine was 15 years old. Shortly afterwards she married Rogerio Alvarado, and it was they who took over management of the island after my father's death. I was sent to Paris and London to receive an education and learn languages. Among other things I studied sugar production, so at the present time I try as best I can to keep the old factory going.”

He waved his arm with an easy going gesture, and the two Norwegians laughed, much relieved as the sinister mood was broken. They understood that Cobos Jr. was a more peaceful and less hard-working man than his notorious father. Obviously he would have liked to live a more intellectually-stimulating life. And he missed the sweet and easy going student life in Paris. “C'est ne pas gay ici,” sighed Cobos, as he emptied his glass and added, “but 15,000 kilos (33,000 pounds) of sugar each month are also sweet!” He rose from his chair and bid his guests good night.

“A Happy Time in the Interesting Pacific Islands”

In the absence of the governor, Cobos and Alvarado gave permission to Bang and Aschehaug to stay for a few months on Floreana. Cobos helped them to obtain a donkey called Conejo for 30 sucres (1 sucre was worth about 1 krone or 15 cents US at that time) and an extra hand for 1 sucre a day in the form of a Chilean, whose real name they could never remember, so they only referred to him as “Chili.”

Supplies were checked and supplemented with three hens and a rooster before Cæsar carried the two adventurers on the last short stretch westward to Floreana. They were put ashore at Black Beach road on the 24th of January, 1922.

Subsequently there followed nearly three months of Robinson Crusoe-like life. They first lived in a tent on the beach but after some days moved up to the old pirate cave in the highlands, about 8 kilometers (5 miles) from Black Beach road.

Here they found rumors to be correct; there were large numbers of domestic animals gone wild, including cattle, horses, donkeys, goats and pigs, but it was far from easy to catch them. It is a paradox in this island group that the indigenous wildlife show little fear of humans yet the feral descendents of domesticated animals brought by sailors and settlers are nearly impossible to approach!

There were also many wild dogs on the island. Together with wild boars and bulls these animals were most feared by the superstitious locals. Some were so afraid of being attacked that when they traveled to Floreana to fish, they refused to walk more than a few yards from the beach. Although nervous, Chili reluctantly agreed to accompany the two Norwegians when they moved into the large pirate cave. Here old names and dates were carved into the soft tuffacious rock around the opening of the cave. Benches, shelves, and a fireplace with a chimney through the roof had also been constructed and remained just as they were for generations. The nearby freshwater spring had obviously attracted many many a visitor.

When night had fallen and darkness stood like a wall against the cave opening, it was important to keep one's imagination under control. The men did not get much sleep until they became accustomed to the songs of crickets, occasionally mixed with the lowing of cattle, and the barking and growling of dogs—and stopped anticipating the sighing and groaning of deceased cave dwellers!

As might be expected, shovels were used for activities other than erecting poles and fences. But they did not find any pirate's treasure around the cave or at the beach.

Animals they managed to catch were intended to be confined behind fences and barbed wire. Some cows were trapped in snares, but after being dragged into the enclosure, they quickly broke out again. Wild donkeys proved too clever to be lured into snares. So, they had to be satisfied with Conejo and the chickens.

Towards the end of March Cæsar dropped anchor again bringing Finn Støren to join his friends. But first, the three went on Cæsar for a week's cruise to Isabela to visit the other settlement in the island group.

Sailing with the current to Isabela was quick. There the Norwegians visited the island's two small villages with a total of a hundred inhabitants. Port Villamil is situated on the southern coast and sightseeing there was soon completed. But to get to Santo Tomás they had to ride inland on horseback for five hours. Just as today, Galápagos saddles were made from hardwood. Unaccustomed to this mode of transportation, three rather stiff and sore tourists late that night crawled back aboard Cæsar.

The return trip to Floreana was a near repetition of the Alexandra cruise 15 years earlier. The hull of Cæsar was well overgrown, and in the plankton-rich water it became worse when the wind abated. For 14 days they tacked and drifted, drifted and tacked, before altogether giving up their attempt to reach Floreana. Instead, they sailed up Isabela's west coast to the famous Tagus Cove. This bay is considered the best harbor in the islands. The numerous names carved and painted on the surrounding cliffs revealed its popularity among sailors, especially from times when tortoises were plentiful. Not a drop of fresh water was to be found here, but with plenty of fish and sea turtles they did not suffer, and could continue their voyage up the west coast and around the northern end of Isabela. Once again they tried to tack south to Floreana.

The old pirate cave was the haunt of Achehoug, Bang and “Chili” for most of the time they were on Floreana. They would close off the cave with a tarpaulin at night and when it rained. Photo from the Norwegian book Galápagos, Verdens Ende: Det Norske Paradis paa Sydamerikas Vestkyst, 1926, Oslo (“Galápagos, World's End: The Norwegian Paradise on South America's West Coast.”)

On the 25th day Cæsar still drifted with limp sails only 20 nautical miles from Isabela's northern tip. The Norwegians realized that they would never return to Black Beach Road. Støren, especially, was upset at having missed the experience of staying ashore, but now there was only talk of survival.

Thirty-five days after leaving Port Villamil they finally arrived at Esmeraldas, mainland Ecuador's northernmost coastal town. The event was described by Per Bang himself: “As quickly as we could we walked to the town's only hotel and ordered a magnificent meal. But being unaccustomed to large amounts of food, the effect was like brandy on a savage, and soon I found myself beneath the table. Thus ended the voyage. But in retrospect I have only pleasant memories about the happy time on the interesting Pacific islands.”

Hopes and Delays

The Galápagos fur seal was once heavily hunted, nearly to the point of extinction. Photo courtesy Allan Hancock Foundation.

The fact that Norwegian and local lives were endangered while aboard Cæsar in 1922 did not seem to frighten the promoters of La Compania de Floreana. Time softens unpleasant memories, and we have to believe Bang when, a few years later, he described the months in Galápagos as such happy ones.

Finn Støren, who spent more time adrift in the waters between the islands than ashore, made some weighty pronouncements:

“At the time I visited the islands there were two colonies, one on San Cristóbal and another on Isabela (Albemarle). The former had about 200, the latter about 100 inhabitants. They were happy people. There were wives who prepared food. A cabin in which to live, food in unlimited quantities, together with total and infinite freedom to be enjoyed in the world's best climate. Is that not happiness? Could one wish for anything better? On San Cristóbal there are about 1,000 acres of cultivated land but there could be tenfold more. The soil is more-or-less free of rocks and easy to cultivate. About 10,000 cattle roam freely, but there is room for 50,000. It is a marvellous island, with water in abundance. Altogether there are five larger islands of similar fertility, some bigger, some smaller than Cristóbal. On these islands there should also be soil for new undertakings. Colonists could settle either on San Cristóbal, Isabela, Floreana, Santa Cruz or Santiago, all of which present great opportunities. The problem of water can be solved satisfactorily. All is arranged by nature so that an industrious and energetic colonist could be happy…”

Støren continues, mentioning commercial enterprises that he thinks would be profitable:

-

Klippfisk.§ prepared from the cod-like grouper, known locally as bacalao. Støren says that it only takes one week to prepare through drying and that there is “…great demand for it in Ecuador and neighboring countries. At the present time it is an industry that yields excellent profits to anyone willing to initiate it.”

- § “Klippe” is Norwegian meaning rock. Rockfish are prepared by leaving the flesh to dry on rocks or on stakes of wood.

- Whale and Seal. Both “… occur in abundance along the coast of Galápagos, and would provide a company with good earnings through judicious management. It is estimated by experts that the region can yield 20-30 thousand barrels of whale oil per year.”

-

Other Fisheries. “Galápagos abounds with lobster, which can be canned for export. Likewise, pearl oysters are found in large quantities in the islands.”§

- § The statement about oysters is in error.

-

Agriculture. Støren describes how practically all tropical fruits, coffee, sugar and all kinds of vegetables are successfully cultivated in the fertile soil. “With rational management there will be business.“

“Cattle have lived on the islands from the time that the first colonists brought them from the mainland. They multiply rapidly and at the present time about 90,000 head live there and thrive on the fertile grassy plains. The wild cattle are large and healthy and easily domesticated. The Ecuadorian government encourages their capture and domestication.“

Støren considers how a Norwegian colony in the islands should be organized after the colonists have arrived. His perceptions are worth quoting, if for no other reason than to reflect the Norwegian attitude about Latin Americans in the 1920s:

“A question repeatedly asked: Why have the Ecuadorians themselves not utilized the islands?“

“The reason, you will see, is that Ecuador is a very large country, about the size of France, but with only two million inhabitants. Of these about 100,000 are whites, while native American Indians compose the bulk of the population.

“These whites, who possess the intelligence and energy, own, for this reason an abundance of good land within the mainland borders. It is inconceivable for an Ecuadorian to look for challenge overseas, all the more since they are not sailors and have little or no understanding of the value of the ocean.

“An Ecuadorian is accustomed to the climate where he now lives, and he sees abundant future work for himself and his family in his own country. They are not interested in other places to colonize, which have the same or perhaps better possibilities.”

If one considers Støren's detailed narrative as well as quotations from the invitation of February 1923 of Ecuador's consul general in Norway, Aug. F. Christensen, one can better understand why so many believed that Galápagos was the land of the future:

Whatever interests Norwegians may have, I will recommend Floreana as the best starting point. What possibilities are there on Floreana and the rest of the islands?

- Firstly as a supply port, since with the opening of the Panamá Canal, there will be ample scope for trade in coal, crude oil and other supplies.

- Whaling, sealing and fishing generally. (Christensen illustrates with quotations from Dr. Wolf who, during an expedition, stated that whales, seals, mussels, fish, sea turtles and lobsters were found in abundance.)

- Colonization.

- The running of hotels and facilities for bathing and recreational opportunities such as hunting and fishing.

-

Cultivation and utilization of the islands' natural resources. These are as follows:

- Salt, lime and sulfur-mines.

- Pastures, where, as mentioned, domestic animals already occur in a semi-wild state, including cattle, donkeys, goats, sheep, pigs and chickens.

- The fertile soil where there is successful cultivation … (He mentions the same domestic plants as did Støren).

- The less fertile soil … (Here he mentions the orchilla lichen for the extraction of dye, wood for fuel, and tortoises for valuable meat and oil.)

- The coastal regions: Land and marine iguanas still occurring in the thousands along with sea turtles, sun themselves on slopes where they lay their tasty eggs.

- And finally, seen from a more scientific point of view, to study and utilize the island's rare and most interesting flora and fauna.

After reviewing at length Ecuador's laws and explaining how well the authorities arrange everything for the colonists (among other things, exemption from tax for ten years with a possible extension), towards the end of the pamphlet, in six foolscap pages, there appears the following:

Until recently the remoteness of this country has been disadvantageous for its participation in world trade, but with the opening of the Panamá Canal there has been a great change. The shipping routes between Ecuador and Europe has been shortened by more than fifty percent. Everyone understands what this means for the country's development. The country's own sons and the foreigners who come to Ecuador, move mainly along the big rivers into the interior to the frontier cocoa plantations, to oil fields, gold and silver mines, and to the valuable forests and extensive plains of the east, leaving the islands in the ocean to the people of sea-faring nations who first settle on them; and why should they not be Norwegians?

And best of all the famous invitation which caught the attention of Norwegians all over the country, and which about 300 took so seriously that they sold their houses, land, and winter clothing:

The Ecuadorian Government welcomes every honest Norwegian.

Quito & Guayaquil, January 1914/February 1923

Aug. F. Christensen

The first expedition needed no advertisement for crew and participants. This was good material for newspapers—a more exotic place could hardly be imagined than the Galápagos Islands in the Pacific. One portrayed a Norwegian trade and whaling station with visions of a Norwegian takeover and settlements complete with Norwegian flags on tall flagpoles in front of white-painted houses!

The consular office in Sandefjord received telephone calls and visits from people who wanted more details, all of whom received a copy of the brochure with the invitation. Summaries were published in newspapers, first throughout Vestfold county, later in the rest of the country.

Christensen and Eilertsen could choose from scores of interested young men, often well-educated. There were craftsmen, agriculturists, engineers and teachers, some of whom were newly educated but out of work and filled with adventurous spirit and self-reliance. At the same time as details about the nature and purpose of the expedition began to take shape, the company decided to buy a Swedish three-masted motor-schooner named Start. She was in good shape, in spite of being built of steel in Scotland back in 1895. Her auxiliary engine was a Swedish Bolinder diesel.

M/S Floreana

Accompanied by a crew of nine, Eilertsen took possession of the schooner at Gævle, Sweden. From there they set sail on December 12, 1924 bound first for Gotland Island to take on a cargo of limestone. Though Start seemed a suitable name for this first expedition ship, the schooner was renamed Floreana.

The trip became unexpectedly difficult for the schooner with its new name and crew. Part of the machinery broke down and Bothnia Bay § was at its winter worst. Plans to get home for Christmas had to be abandoned.

§ Part of the Gulf of Bothnia between Sweden and Finland.

On Christmas Eve they found shelter in a small Swedish port. The next phase of the voyage became even more dramatic when, during a storm, the chief engineer suddenly became unconscious. Eilertsen accepted an offer of assistance from a steamer and sailed into Copenhagen. At the hospital the sick man was found to be suffering from a brain hemorrhage. A new engineer-machinist was hired, and after a delay of eight days in Denmark, Floreana was on her way to Sarpsborg, Norway. Here they unloaded the limestone before the last short trip across the Oslofjord to Sandefjord.

Meanwhile, the newspapers Amtstidende and Tønsberg Blad eagerly latched onto rumors of near wreckage, unpaid salvage wages, an epidemic among the crew and quarantine in Copenhagen. Apparently, many members should have withdrawn from the expedition.

The following day it was all denied by Christensen. “Nonsense, utter rubbish and amazing intrigue,” he stated bluntly. According to Christensen, the rumors originated from a man in Larvik whose request to participate in the expedition had been declined because of poor conduct.

Expedition to Galápagos

Beginning in November 1924, newspapers carried news of La Colonia de Floreana and Christensen's planned Galápagos expedition. A photo in Sandefjords Blad, January 2, 1925 shows the future expedition ship in Sweden while still named Start.

Caption under photo (not shown): As a follow-up to our article of Wednesday about the expedition to the Galápagos Islands, we now present a few pictures. Upper left: A view of the Galápagos Islands with Narborough Island seen in the background, whose peak has never been climbed. Below: The expedition ship “Floreana,” which was purchased in Sweden and belongs to Consul August F. Christensen, Sandefjord (seated at right, with dog).

At the end of January 1925, Floreana finally arrived from Sarpsborg and lay to at Stub in the fjord of Sandefjord. The pilot Jensen Eian guided her on this stretch and could not praise the schooner enough, her hull, rigging and engine being the best. He comments to Sandefjord's newspaper: “Had I been a little younger, I would have joined this expedition.” Jensen Eian's weighty statement stopped the rumors for the time being.

The A/S Framnæs Mek. shipyard in Sandefjord was founded by Aug. F. Christensen's father, Christen Christensen. Family ties and contacts are welcome in order to get Floreana fitted out expertly, yet cheaply. Now that people have a ship to look at during their Sunday strolls, the local interest increases noticeably. Journalists jump on every story, and the newspapers print “Galápagos News.” But no more sensational news.

In the spring of 1925, larger headlines are employed when the Trading Bank admits a deficit of 48 million kroners, and the Prime Minister, Johan L. Mowinckel, demands a government investigation of his predecessor and party associate, Abraham Berge, to find the perpetrator. On other pages, one is consoled by the speed skater Ivar Ballangrud's promising results and Roald Amundsen's many attempts to fly across the North Pole.

Oslo Museum Curator Alf Wollebæk was to accompany the Floreana expedition for several months to study nature and the animal life. He was one of Norway's best-known zoologists.

On the 23rd of January it is reported that the well-known Oslo zoologist-curator, Alf Wollebæk, will travel in advance to South America and work there for a period before Floreana arrives.

Christensen also chooses to join the expedition in Guayaquil. The leader for the 20 aboard is to be Eilertsen, and departure is planned for March. However, the two short winter months allowed for rebuilding and outfitting the ship together with countless other preparations, proved to be far too little time. In the beginning of May the vessel is still at the shipyard.

In the Østlandsposten of May 9th there is an interview with the engineer, Ludvig Næss, recently graduated from a university in Germany. He will serve as electrician. Like the others, he had paid the company his capital share of 3,000 kroner, but will in return receive a monthly salary of 185 kroner for a contract period of 18 months, at the end of which the contract may be extended, or the company will pay his fare home.

In addition to the expedition participants, the shareholders are mostly Christensen's friends and family members. Later, when the money ran out and investments were lost, he had to endure a lot of criticism. “It is not the custom to pay salary to colonists.” Christensen had a reason for doing this. Although he personally was convinced that the colonization attempt would succeed, the salary assured participants against a great personal loss in case of failure. Consequently, those who were with the Floreana expedition did not end up in such misery as did many in following expeditions.

The Østlandsposten interview not only reveals that the Floreana was much delayed, but now we also read that the leader and captain for the voyage will be “the old Pacific sea-dog” Anton Stub from Sandefjord. When the colony is established, the leader ashore will be Captain Axel Seeberg from Tønsberg, with Olaf Eilertsen second in command. No explanation is offered as to why Eilertsen no longer is in charge.

“A modern Viking adventure”

Tidens Tegn (“Sign of the Times“) § in Oslo prints frequent articles about the “Galápagos fever” that is gripping more and more Norwegians. Saturday 28 February, 1925:

§ This newspaper is now called Verdens Gang (The Way of the World), or just VG for short and is still one of Norway's biggest papers.

As mentioned before, Aug. F. Christensen has founded a company for the purpose of exploiting opportunities on and near the Ecuadorian archipelago of Galápagos, situated at the very low latitude of zero. However, Sandefjord's high society has, so-to-speak, already visited the islands. There was to be a carnival. What could be more appropriate than to use as theme the land of our most recent enterprise—the future Norwegian colony in the Pacific? The carnival was held in the Hotel Atlantic's splendid banquet hall. Dressed in festive and colorful costumes in the changing light of the chandeliers, projectors and reflectors, they danced and celebrated with their more-or-less recognizable partners—while the excellent private ‘Jazzband Speed’ kept blaring out the newest Paris tunes. The successful arrangement was, however, due to the efforts of the painter Trygve Fleischer who was then living in Sandefjord and who had decorated the room. Upon a large and splendid curtain backdrop and a number of posters, Mr. Fleischer had recreated the sultry, enticing atmosphere of tropical islands. Paintings of some beautiful creatures enhanced the whole effect …

That Galápagos had palm-fringed beaches was a widespread misconception.

One of Tidens Tegn's regular journalists was Øvre Richter Frich, the creator of the Jonas Fjeld novels. In April he has a column with the headline “A Modern Viking Adventure.” His article reports more thoroughly than many others about Galápagos. He does not hide his admiration for the planned expedition, but says nothing about palm groves and a south-sea paradise:

We are still not lacking in good old Viking spirit in this country. Roald Amundsen will soon spread his wings towards a secret adventure. There is a new, powerful and sporty tendency, to answer many questions which scientists, with relentless and never-ending curiosity, are asking. On the day when Amundsen and his men see Spitzbergen disappear behind them, a world of scientists and athletes will watch with bated breath.

But nobody appears to hold his breath or feel any great expectation for the day when the Galápagos Expedition leaves to settle in a nearly unknown world. Yet, this is more of an adventure than anyone can imagine. As for myself, I confess that I would rather enjoy being a Viking aboard, bound for this shore of destiny. When a farmer's son leaves his home in search of greener pastures, he probably is driven by a conscious or unconscious longing for adventure. But the adventures that the USA offers her citizens are of a rather questionable kind. The emigrant goes from ordinary drudgery to greater drudgery. He offers his strength and his good sound peasant blood to another society, more-or-less free. He leaves an established, inherited farmers' culture for an uncertain hybrid hodge-podge which does not add an inch to his spiritual growth. With this Galápagos expedition it is quite another matter. This is a new enterprise, a fresh initiative, a brave and daring expression of our national inherited need for adventure and action. Yes, there will also be toil, but there is adventure in this toil. When he left his mother country, William Penn did not know more about North America than the people who now set their course for Panamá know about the strangest archipelago in the Pacific.

Towards Galápagos

Floreana laying at Stub in Sandefjord while being refitted and prepared for the expedition. She was 45 meters (148 feet) long, with a gross weight of 410 tons. Photo courtesy Norwegian Maritime Museum.

Early in the morning of Friday the 15th of May, 1925, Floreana sails out of the Sandefjord Fjord. In the hold is stowed a cargo of 330 tons of sacked cement for Ecuador, together with the expedition equipment: Materials and fixtures for the main building, a combined generator and telegraph station complete with a steam engine, boilers and tanks, barrels with oil, kerosene and gasoline. Additionally, there are materials for the construction of a dock, steel tracks with trolleys, 3,000 meters (3,280 yards) of water pipes, dynamite, arms and ammunition, tools of all kinds, fishing equipment, provisions, medicines, 400 books for a library, a flagpole and a croquet set!

Two motorboats are firmly secured on deck beneath a tarpaulin.

Of the twenty men aboard Floreana seven are sailors. Most of the eighteen Norwegian men are from the southeastern part of the country, and the other two are Finnish-Norwegians, one of whom is the author John William Nylander. He was originally a sailor, has written novels about the sea, but he is also known for his book about the Greek civil war. Now he wants to closely study the Norwegian colonization attempt.

The seven non-sailors are: an agriculturist, a civil engineer, an accountant, a fisherman, a blacksmith, a hotel manager, and a teacher. Originally there was to have been a participant with expertise in food canning but the plans for a cannery are temporarily postponed.

Also, Captain Olaf Eilertsen is not on board. The plan now is that he will leave later with the vessel Isabela, a 39-foot former pilot cutter designed by Colin Archer. La Compania de Floreana bought the vessel in order to assure communication with the continent and the other islands.

For the time being the participants are happily unaware that most of the optimistic plans will not be realized.

Most of the crew aboard Floreana are “skårunger” § or first-time sailors, including the teacher, Knut Øvreberg. On the 17th of May, the Norwegian National Day, he stands hunched over the railing with several others, shivering with white knuckles clutching the hand rail while sacrificing his meal to Neptune and the crabs.

§ A newly-hatched seagull chick or one that is still feathered in down.

“ … and thus I parted with my Viking spirit, if I ever had one. Poor landlubber me, I sacrificed my lot, yes, and maybe much more than I could afford. Hence the general mood was pretty depressed on the glorious 17th of May.”

Øvreberg had left work and home in Larvik, but originally he came from Stryn in West Norway. He was a compulsive writer and longtime contributor to the Norwegian newspaper Dølen. About the notorious gale in the Bay of Biscay he relates:

“ … on Friday we had a stiff gale which I will call a severe storm. The yankee (a large triangular head sail on the bowsprit) was torn apart like a rotten piece of paper. Soon after, the forward gaff was broken. The vessel tossed and danced about in the sea so I could hardly stay on my feet. During the night, while sleeping soundly, I was rudely awakened and got up to reef sail. The wind howled and screamed in the rigging, the sea roared and swirled so that it was almost impossible to hear a human voice.”

It is hardly better back in the bunks. The gale roars for six days and nights, during two of which it is so severe that the ship lies hove to. The lurching is violent. The ship is heavily laden and with little freeboard; more than once the doghouse and the galley are awash. Øvreberg lies awake and listens to the waves wash over the deck and gush through the scuppers. Fantasy runs wild. Maybe the oil barrels have gone adrift and are making holes in the ship's side? The slushing sound is water entering the hull! And what about the ammunition—could the rolling not cause an explosion?

Knut Øvreberg hides his head under the pillow and tries to ignore the noise, and wonders why he ever left that quiet job behind the desk.

Colonists in cheerul anticipation before the departure from Sandefjord. Photo courtesy Netta Næss.

This bout of foul weather is the only one during the entire crossing, and soon seasickness is forgotten and good humor prevails. All take a turn at the wheel. The skipper is an old salt and although the motor is running nearly all the time, they have the sails hoisted. For this reason keeping a straight course is not always easy; the wake is often crooked, sails start slamming aloft and curses fly from the bridge. But quickly the landcrabs become full-blown helmsmen.

On June 1, there is a short stop at Madeira to fuel, and then on to the Atlantic proper. Flying fish are served for breakfast, and for dinner there's an occasional tuna. Some study Spanish under an awning, while others are exercising, followed by a bucket shower. Everyone is discussing the adventure which has hardly begun.

The atmosphere on board is good. After 18 days they reach Barbados in the West Indies and anchor in Carlisle Bay. Here, black boys paddle out to the ship and offer to dive for coins. Øvreberg throws out a Norwegian krone: “ … when one of the boys came up with the coin in his hand, he saw the hole in the coin, made a face and cursed me in the worst possible way. Later he could not to be tempted back in the water!”

A midsummernight celebration on deck in the Caribbean Sea becomes a musical happening. The five-man orchestra consists of a mandolin, violin, flute, accordion and a drum. The choir is led by Øvreberg and the ten perform their premiere concert entitled “Tortoise.”

The then 11-year old Panamá Canal is traversed without any problems, and in the afternoon of July 9th, Floreana drops anchor outside Isla Puná at the mouth of the Guayas River on Ecuador's Pacific coast. They signal for a pilot and after a while a motorboat arrives with the latest local news:

A revolution has started this very same morning!

The man in the boat calms the frightened Norwegians, stating that the counter-revolutionaries are already back in command in Quito and Guayaquil, so a pilot will be available. Before the change of tide about midnight, a man indeed boards the ship. He guarantees that the old government is still in power and that there should be no risk in continuing up the Guayas to the main port town. In the tropical darkness Floreana navigates up the last thirty nautical miles.

Stormy weather in the Bay of Biscay, with Alfred Waardahl at the helm. Photo courtesy Netta Næss.

Next morning 20 men are lined up at the rail studying the busy harbor. They perspire at the least exertion, and the air is so warm and humid, that even breathing seems heavy. Still, the water is alive with small and medium sized rowboats buzzing about. Soon the authorities arrive on board, accompanied by the Norwegian consul Haakon Bryhn and Alf Wollebæk. The zoologist from the Oslo Museum has finally been rewarded after several weeks of patient waiting at Guayaquil. Wollebæk relates that during one-and-a-half days of shooting and street fighting he remained in hiding in the hotel. It now appears that the revolution has ended as quickly as it started.

Because of the political unrest, another person has been delayed in his travel through the country. But on July 17th a harbor taxi approaches Floreana where she lies turning with the tide while anchored in the river. In the bow sits a gentleman impeccably dressed in a suit with tie and straw hat. Aug. F. Christensen briskly climbs the ladder, shakes everybody's hand and congratulates them on their successful crossing, which they accomplished in 57 days.

Left: Still 7,000 nautical miles to go and as yet no indication of a warmer climate.

Right: Finally, trade winds and tropical temperatures. Ludvig Næss and Rolf Sønderskov take a bucket-shower on deck. Photos courtesy Netta Næss.

The crew of Floreana remembers the 14 days in Guayaquil as one continuous series of parties. Enthusiasm for life ashore is easy to understand. Only a few had received permission for shore leave while at anchor in Madeira, Barbados and in the Canal Zone, and then only in connection with refueling and obtaining fresh fruits and vegetables. Captain Stub did not want to run the risk of someone becoming involved with “women or liquors or even worse things,” as he remarked. Concerning what might be even worse things, he declared “women and liquor combined!”