A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean

and Round the World

1791-1795

George Vancouver

This page contains only those sections of the indicated chapters that pertain to the Galápagos Islands. Spelling variations of “Galápagos” follow original text. Introduction and numbered footnotes in brackets [replaced here by †, ‡ & ^ symbols] by editor W. Kaye Lamb in Hakluyt Society reprint edition. Footnote with asterisk is Vancouver's own, and as elsewhere, § is a footnote introduced in this online page. Footnotes appear immediately after the paragraph in which they are cited. Footnotes in Introduction refer to the 1795 segments of the following documents:

- Baker: Lieutenant Joseph Baker on HMS Discovery. Mss. at Public Record Office PRO {now, National Archives at Kew, United Kingdom}

- Menzies: Archibald Menzies, botanist and acting surgeon on HMS Discovery. Personal Journal, 21 February 1794 - 18 February 1795. Manuscript Collection, National Public Library of Australia, Canberra

All dates in this text are February, 1795.

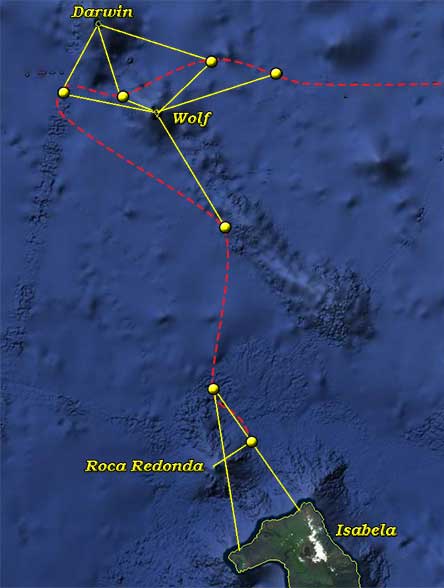

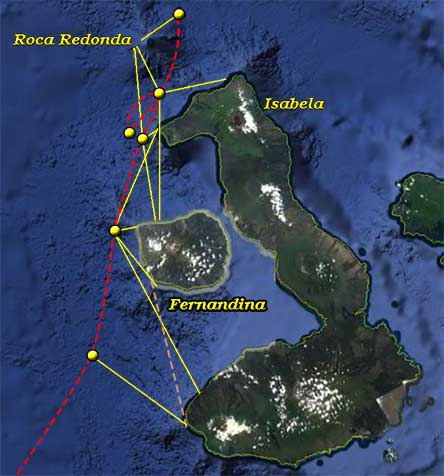

Charts by Baker and Johnstone show tracks of HMS Discovery and Chatham, respectively, through the islands.

Introduction (Excerpt)

From Cocos Island the ships sailed slowly southward. The intention was that they should rendezvous at Islas Juan Fernandez, to replenish their wood and water. On the way Vancouver hoped he might encounter the Galapagos Islands and discover their position. Any expectation of doing so seemed to have vanished when they stumbled upon two small islands that proved to be the northernmost of the group. Sailing on southward the ships passed down the western shore of Albemarle (Isabela) much the largest of the Galapagos, and Narborough (Fernandina) Island, which lies so close to it that for a time Vancouver thought they were one. The islands, volcanic in origin, are forbidding in appearance. Menzies considered them “the most dreary barren and desolate country I ever beheld,”† while Baker described Albemarle as being “nothing but a large Cinder, without any sign of Verdure or Vegetation.‡ But when Whidbey and Menzies landed at the northern end of Albemarle, like many later visitors they were astonished to find it teeming with life and populated by a curious blend of tropical and polar beasts and birds: “with Seals & Penguins in vast abundance, whilst the surface of the adjacent sea … swarmed with large Lizards swimming about in different directions & basking at their ease.”^ They saw none of the famous giant tortoises, from which the islands derived their name, as they lived high up in the vegetation on the slopes of the volcanoes. Nor did Menzies become aware of the unique nature of the islands. Each, in Jacques Cousteau's phrase, “seems to be a closed universe” in which animals have evolved over the centuries without outside contacts.

† Menzies, 7 February 1795.

‡ Baker, 8 February 1795.

^ Menzies, 7 February 1795.

The Galapagos were left behind on February 10. Within a week Vancouver had become so impatient with the poor sailing of the Chatham that he decided to part company with her and hurry on to Juan Fernandez, where he ordered Puget to join him.

Book the Sixth.

Passage to the Southward along the Western Coast of America;

Double Cape Horn; Touch at St. Helena; Arrive in England.

Chapter II

Depart from Nootka Sound—Violent storm—Arrive at Monterrey—Receive on board the deserters from the Chatham and Daedalus—Excursion into the country—Examine a very remarkable mountain—Astronomical and nautical observations.

… as I had no intentions of visiting any part of the American coast to the northward of the 44th degree of south latitude, I purposed that our course from hence {from Monterrey} should be directed towards that latitude without stopping, unless we should be so fortunate as to fall in with the Gallapagos Islands, whose undefined situation I much wished correctly to ascertain; and of course it would neceessarily be some time before we reached our resting place.

Chapter III

Lower Monterrey—Some account of the three Marias Islands—Proceed to the southward—Astronomical and nautical observations.

The American coast to the southward of cape Corientes not continuing to take a direction favorable to our route, we were no longer desirous of keeping near its shores, and I therefore made the best of our way towards the island of Cocos and the Gallipagos, with an intention of stopping at one or both of those places.

Chapter IV

Visit the island of Cocos—Some description of that island—Astronomical and nautical observations there—Proceed to the southward—Pass between Wenman's and Culpepper's islands—See the Gallipagos Islands, and ascertain their situation.

The wind which now hung far to the south, obliged us to make a much more westerly course than I could have wished, as I had entertained hopes of being able to pass near enough to the Gallipagos islands† to have had an opportunity of ascertaining their true situation; but as the westernmost of them are said to be under the meridian of the island of Cocos, which was now nearly three degrees to the eastward of us, the chance of succeeding in this expectation was now so little, that I gave up every idea of accomplishing that object.

† The Galapagos Islands; officially the Archipiélago de Colón, so named by Ecuador, which claimed them in 1832.

Land was discovered on Monday forenoon to the W.S.W.; it then appeared to be a very small island,† which at noon bore by compass S. 72 W., eight or nine leagues distant. As our observed latitude was 1° 26', longitude 268° 43', and the variation of the compass 8° eastwardly, we appeared to have been set in the course of the last twenty-four hours 10 miles to the north, and 28 miles to the westward. The influence of this current setting to the W.N.W. was very perceptible, for although with a light air of wind during the afternoon our course was directed to the south-westward, yet so rapidly were we driven in the above direction of the current, that, at sun-set, this island bore by compass S. 46 W., and another island,‡ which had been discovered about an hour and an half before, bore, at the same time, N. 72 W. During the night we had a light breeze from the S.S.W., with which we stood to the S.E.; but so far were we from stemming the current, that, at day-light on the following morning, Tuesday the 3d, the first of these islands bore by compass S. 68 E., distant six leagues, and the second N. 17 W., 12 miles distant. At such a rate had we been driven by the current between these islands, that notwithstanding we used every endeavour to preserve our station by keeping as the wind veered on the most advantageous tacks, yet, at noon, the first island bore by compass E. by S., at the distance of nine leagues, and the other N.N.E. ½ E., at the distance of 17 miles. In this situation the observed latitude was 1° 28', longitude 267° 49', by which the current appeared to have set us, since the preceding day at noon, ten miles to the north, and fifty miles to the westward.

† The principal islands were first named in English in 1684 by Captain Ambrosia Cowley, a buccaneer; several of the smaller ones were named by Colnett in 1794. Most of them have since received official Ecuadorian names; some have had several names. This first island seen was Cowley's Wenman Island, now officially named Wolf. The name is wrongly spelled Wenams on Colnett's chart.

‡ Culpepper Island (now Darwin Island).

In passing between these islands, which lie from each other N. 42 W. and S. 42 E., at the distance of twenty-one miles, we observed neither danger nor obstruction; the southernmost, which is the largest, did not appear to exceed four miles in circuit, and the northernmost about half a league; the former is situated in latitude 1° 22' 30", and longitude 268° 16'. Its north-western side forms a kind of long saddle hill, the northern part of which is highest in the middle, and shoots out into a low point, which at first sight was considered by us to be an islet, but was afterwards believed to be united. A small peaked neck or island lies off its south-west side, which, like all the other parts of it, excepting that towards the north, is composed of perpendicular naked rocky cliffs. On the low north-west part we saw what we supposed to be trees, but we were by no means certain, for the island in general presented to us a very dreary and unproductive appearance. The northernmost island rose in naked rocky cliffs from the sea, off which are two islets, or small rocks; that on its east side is remarkable for its flat table top, and for its being perforated nearly in the middle. The situation of these islands, the easternmost being nearly 5° to the westward of the meridian of the island of Cocos, gave us at first reason to suppose them a new discovery, and not a part of the group of the Gallipagos, as all the ancient accounts agree in placing the Cocos due north from the westernmost of that cluster of islands; but when we took into consideration the very rapid currents by which we had been controlled, they easily accounted for errors to which other navigators must necessarily have been subjected, who have not, like ourselves, been so well provided with the means of ascertaining the full effect of their influence; which had, since our leaving that island, produced a disagreement of upwards of two degrees of longitude in our dead reckoning. The decision of this point remained, therefore, to be determined by our further progress to the south; for, in the event of the first or southernmost, being Wenman's island, and the most northern, that called Culpepper's island, the northernmost of that group of islands, little doubt was entertained of our meeting with more of them in pursuing our southern course; in doing which we were not very expeditious the two succeeding days, as the wind between S.W.W. and S.S.E. was very variable in point of strength; and although we endeavoured to take every advantage it afforded, so little progress did we make against the adverse current, that on the 5th, the most southern of these two islands was still in sight, and at noon bore by compass N. 31 W., distant eight or nine leagues. The observed latitude at this time was 59', longitude 268°27', by the dead reckoning 271° 24'; having, in the last twenty-four hours, been set by the current seven miles to the north, and forty-eight miles to the westward. As we were now approaching the equator, and as the sea was tolerably smooth, some further observations were made on the vertical inclination of the magnetic needle, which shewed

| The marked end | North face | East, | 7° 8' | |

| Ditto | ditto | West, | 8° 3' | |

| Ditto | South face | East, | 7° 28' | |

| Ditto | ditto | West, | 7° 18' | |

| Mean inclination, | 7° 28' | |||

| The variation of the compass, at the same time, | 8° eastwardly. | |||

|

|

|---|---|

| HMS Discovery track through the Galápagos Islands. Yellow circles indicate ship's position when Vancouver took bearings to indicated locations. |

Google Earth View shows latitude/longitude coordinates which Vancouver gives in addition to the bearings seen in the above illustrations.

Google Earth View shows latitude/longitude coordinates which Vancouver gives in addition to the bearings seen in the above illustrations.

We advanced so slowly from these islands, that at sun-set the southernmost of them was still within our view, bearing by compass N. 12 W. The wind was mostly at S.S.W. during the night, with this we stood to the southeastward, and at day-light on Friday morning the 6th, discovered a more extensive land than the two islands we had just passed,† bearing by compass from S. 10 E. to S. 35 E. This land appeared to be very lofty, to be at a considerable distance from us, and to be divided into three or more islands; but as we approached it the less elevated parts were seen to be connected, so that, in the forenoon, it seemed to be only divided into two portions, and even this division was rendered doubtful, as we drew nearer to it, by the low land rising to view until about noon, when the whole extended by compass from S. 42 E. to S. 10 E. with a detached rock S. 2 W. In this situation the observed latitude was 28' north, the longitude 268° 32'; having been set, in the last twenty-four hours, by the current twenty-six miles to the westward. This, however, appeared to have taken place in the early part of that day, as since our having made the land in the morning, we had approached it with a light breeze, without having apparently been influenced by any current whatever.

† Albemarle Island (officially Isabela), much the largest of the islands.

In the afternoon a pleasant breeze sprang up from the south-westward, with which we stood close-hauled in for the land, and before sun-set saw very plainly, that what we had for some hours before considered to be two islands, was all connected by depressed land on which was a hummock that had also appeared like a small island; and beyond this low land, at a considerable distance to the southward, was seen an extensive lofty table mountain. The land immediately before us formed also towards its eastern extremity a similar table mountain, and towards its western point a very regular shaped round mountain, which, though not of equal height to the others, was yet of considerable elevation, and in this point of view seemed to descend with great uniformity. The easternmost, terminating in a low point with some small hummocks upon it, at six in the evening bore by compass S. 47 E.; the westernmost, which terminated more abruptly, S. 13 W.; and the detached rock,† which is steep, with a flat top, S. 71 W. The whole of this connected land appeared now to form an extensive lofty tract; and as I had no intention of stopping, the object for consideration was, on which side we should be most likely to make the best passage? The south-west wind from its steadiness, and the appearance of the weather, seemed to be fixed in that quarter, and as we approached the shore we found a strong current setting to windward; I therefore did not hesitate to use our endeavours to pass to the westward of this island, which under all circumstances appeared to me to be the best plan to pursue.

† Roca Redonda.

We drew in with the island until about nine at night, when we were within about a league of its shores, and finding that the windward current was the strongest near to the land, the night was employed in making short trips between the shores of the island and the flat rock before mentioned, frequently trying for soundings with 100 fathoms of line without success. On Saturday the 7th, we were nearly up with the western extremity of the island, and as the weather was fair and pleasant with a very gentle breeze of wind, I wished, whilst the ship was turning up along shore, to acquire some knowledge of what the country consisted, and for that purpose immediately after breakfast Mr. Whidbey, accompanied by Mr. Menzies, was dispatched with orders to land somewhere to the southward of the western extremity of the land then in sight, which had been named Cape Berkeley.† The part of the island we were now opposite to, and that which we were near to the preceding evening forming its north-western side, either shoots out into long, low black points, or terminates in abrupt cliffs of no great hieght, without any appearance of affording anchorage or shelter for shipping. The surf broke on every part of the shores with much violence, and the country wore a very dreary desolate aspect, being destitute of wood, and nearly so of verdure to a considerable distance from the sea side, until near the summit of the mountains, and particularly on that which formed nearly the north-western part of the island; where vegetation, though in no very flourishing state, had existence.

† The NW point of Albemarle Island; named by Colnett in 1794. He paid two visits to the Galapagos, one in June 1793 and the other in March, April and May of 1794. For accounts of them see A Voyage to the South Atlantic, pp. 47-60, 145-59. Colnett's chart§ of the islands (opp. p. 46) is the first “that could be considered as workable.” Colnett's Voyage was not published until 1798, the year of Vancouver's death, but a later footnote indicates that Vancouver was aware of its contents while working on his own narrative.

§ The “Chart of the Galapagos” is by Aaron Arrowsmith, 1798.

The observed latitude at noon, being then within four of five miles of its shores, was 7½' north, the longitude 268° 29½'; in which situation the steep flat rock, called Redondo rock, bore by compass N. 26 W.; the easternmost part of the island now in sight, N. 78 E., and Cape Berkeley in a line with more distant land, supposed by us to be another island, south.§ As we advanced, the regular round mountain assumed a more peaked shape, and descending with some inequalities, terminated at the north-west extremity in a low barren rocky point, situated according to our observations in latitude 2' north, 268° 30' east. From it the steep flat rock lies N. 2 W., distant 12 miles; and the shores of the north-west side of the island, so far as we traced them, took a direction about N. 50 E. sixteen miles; the wind for the most part of the day continued light and variable between the west and S.W., but with the help of the current which still continued to run in our favour, we passed in the afternoon to the south of Cape Berkeley, from whence the shores to the southward of that point take a rounding turn to the eastward, and shoot out into low rocky points. The interior country exhibited the most shattered, broken, and confused landscape I ever beheld, seemingly as if formed of the mouths of innumerable craters of various heights and different sizes. This opinion was confirmed about five in the afternoon on the return of Mr. Whidbey and his party, from whom I understood, that about two leagues to the east south-eastward of Cape Berkeley, a bay had been discovered† round a very remarkable hummock, which seemed likely to afford tolerable good anchorage and shelter from the prevailing winds; but as Mr. Whidbey had little time to spare, and as the shores afforded neither fuel nor fresh water, he was not very particular in this examination, but endeavoured to gain some knowledge concerning the general productions of the country. During the short time the gentlemen were so employed on shore, those remaining in the boat, with only two hooks and lines, nearly loaded her with exceedingly fine fish, sufficient for ourselves, and some to spare for the Chatham. Our opinion, that this part of the island had been greatly subject to volcanic eruptions, appeared by this visit to have been well founded; since it should seem, that it is either indebted for its elevation above the surface of the ocean to volcanic powers, or that at no very remote period it had been so profusely covered with volcanic matter, as to render its surface incapable of more than the bare existence of vegetables; as a few only were found to be produced in the chasms or broken surface of the lava, of which the substratum of the whole island seemed to be composed. Instead of the different species of turtles which are generally found in the tropical, or equatorial regions, these shores, however singular it may seem, abounded with that description of those animals which are usually met with in the temperate zones, bordering on the arctic and antarctic cicles:‡ the penguin and seals also, some of which latter I understood were of that tribe which are considered to be of the fur kind, were seen, as likewise some guanas and snakes; these, together with a few birds, of which in point of number the dove bore the greatest proportion, were what appeared principally to compose the inhabitants of this island; with which, from its very uncommon appearance, I was very desirous to have become better acquainted; but we had now no time to spare for such an inquiry, nor should I indeed have been able personally to have indulged my curiosity, as I still continued to labour under a very indifferent state of health, which in several other instances had deprived me of similar gratifications.

§ Narborough Island, now Isla Fernandina.

† Banks Bay, named by Colnett for Sir Joseph Banks.

‡ The Vancouver expedition was encountering conditions that have fascinated naturalists, probably caused by the meeting of warm and cold ocean currents in the vicinity of the Galapagos. “This mixture of warm and cold waters has had a considerable impact upon the flora and fauna of the islands. … The fauna represents a strange mixture of tropical and polar species. There are penguins and albatrosses, sea lions, seals—all of which we are accustomed to find, not in the tropics, but in the far North. … In the midst of these cold-water animals, we find iguanas, turtles, and even warm-water snakes.”—Jacques-Ives Cousteau, Three Adventures (New York, 1973), pp. 28-9. Menzies' first-hand account reads: “We rowed towards the North West Point [of Albemarle Island], near which we landed, & to our great astonishment found these rugged shores on the equator, inhabited with Seals & Penguins in vast abundance, whilst the surface of the adjacent sea that laved them with its surf, swarmed with large Lizards swimming about in different directions & basking at their ease. … We saw another kind of a large Lizard burrowing in holes amongst the rocky lava, & three or four smaller ones of the same genus, with a few snakes but none of them large. The birds we saw about the shore besides the Penguins were Pelicans, Great & brown boobies, Noddies, Sea Pies, Gulls, Terns, & a beautiful white winged Dove, which as it was a new species I named Columba leucoptera.” As for the landscape, “Upon the whole it formed the most dreary barren & desolate country I ever beheld.”—February 7.

At sun-set the steep flat rock bore by compass N. 5 W. and the land in sight from N. 56 W. to S. 9 E.; the former, being the north-west point of the island, and the latter, the land that was stated at noon to be in a line with it, still at a considerable distance from us; both of which seemed to form very projecting points, from whence the shores retired far to the eastward; but whether only a deep bay was thus formed, or whether the land was here divided into two separate islands, our distance was too great to determine.

In the evening the wind freshened from the S.S.W. with which we plied to the southward, and having still the stream in our favor, we kept near the shore where the current continued to be the strongest. At midnight this breeze was succeeded by a calm, which lasted until day-light the next morning, when, with a light breeze, and the assistance of the current, we made some progress along shore. As we advanced, land further distant, and apparently detached, was discovered to the S.S.E.; at noon the observed latitude was 18½' south, the longitude 268°23'; in this situation we were opposite to the land mentioned the preceding day at noon. This takes a circular form, and shoots into several small low projecting points. From the most conspicuous of these, called cape Douglas,† the adjacent shores take on one side a north-eastwardly, and on the other a southerly, direction. The above, being the nearest shore, bore by compass N. 78 E. distant five miles; the southernmost part of this land in sight S. 39 E.; the west point of the last-discovered detached land, which is named Christopher's point,‡ S. 28 E.; and Cape Berkeley N. 14 W.§§ The land we were now abreast of bore a strong resemblance to that seen the preceding day, equally barren and dreary towards the sea-side, but giving nourishment to a few scattered vegetable productions on the more elevated part, which rose to a table mountain of considerable height and magnitude, and is the fourth mountain of this table-like form of which this land is composed.

† The NW point of Narborough Island (officially Fernandina). Vancouver had not yet realized that this island, which lies close to the W side of Albemarle Island, was detached from it.§

§ But earlier, Vancouver wrote that this land was “…supposed by us to be another island.”

‡ The SW point of Albemarle Island; not on “detached land,” as Vancouver first supposed.

§§ The bearing to Cape Berkeley is assumed to be in error. In order to agree with the other bearings, it should be about N. 24 E., as shown on the chart above.

The wind, during the afternoon and night, blew a gentle breeze from the southward, but as we continued to be assisted by the current setting to windward, we made some progress in that direction, and were sufficiently to the southward the next morning, Monday the 9th, to ascertain pretty clearly that the last-discovered land, now bearing S. 54 E. distant nine leagues, was distinct from the second discovered land, or island; and that its western part, Christopher's point, lies from the south point of the second-discovered land, which is called cape Hamond, S. 13 E. at the distance of twenty miles.†§

† Vancouver later sorts out the geographical confusion that exists here. At this point he thought the land group consisted of three parts: the N part of Albemarle Island (the first of the three discovered); Narborough Island, lying in front of Albemarle Island (“the second land discovered”) and the S part of Albemarle Island (“the last-discovered land”). Cape Hammond is the S point of Narborough Island. All these names appear on Colnett's chart.

§ Actually, the distance is about thirty miles, as indicated by dashed line on Fernandina/Isabela illustration above.

Thus concluded our examination of these shores, which proved to be those of the Gallipagos islands. The wind now seemed to be settled in the south-eastern quarter, blowing a steady pleasant gale; and as the weather was fine, we were once more flattered with the pleasing hopes of having at length reached the regular south-east trade wind; we therefore made the best of our way to the south-westward with all sail set, and at noon observed we were in latitude 44' south. The longitude by the several chronometers, agreeably to their rates as ascertained at the island of Cocos, was by

| Arnold's No. 14 | 267° 54' 30" |

| Ditto 176 | 267° 52' 45" |

| Kendall's | 267° 52' 30" |

| But by the dead reckoning it appeared to be | 272° 2' 0" |

The variation of the surveying compass was 8° eastwardly, and the vertical inclination of the marine dipping needle was,

| Marked End | North face | East, | 2° 50' | |

| Ditto | ditto | West, | 2° 45' | |

| Ditto | South face | East, | 2° 30' | |

| Ditto | ditto | West, | 2° 30' | |

| Mean inclination of the north point of the marine dipping needle, | 2° 29' | |||

The very exact correspondence of the longitude by the chronometers, and which had uniformly been the case ever since our departure from the island of Cocos, induced me to believe, that at least the relative position in point of longitude of that island with these would be found correct; and I trust, that the means adopted to ascertain the longitude of the former, will not be found liable to any material error.

On reference to the relative position of the land to which our attention had been diverted since the 6th of this month, the delineation of its shores from our observations, will be found to bear a very striking resemblance to that of the westernmost of the Gallipagos, as laid down in Captain Cook's {sic, Colnett's} general chart; and although the situation of Wenman's island does not correctly agree, yet the correspondence of the larger portions of the land with the above chart, is doubtless a further confirmation of their being the same as is therein intended to be represented; from whence I should suppose,* that the first and third portion of land seen by us constituted Albemarle island, and that the second was Narborough's island. These names were given by the Buccaneers, as also that of Rodondo rock to the steep flat rock, and Christopher's point to the west point of the third land; and under this persuasion, this is the south-west point of Marlborough† island, which is situated according to our observations in latitude 50' south, longitude 268° 34' east.‡

* This conjecture was on my return to England fully confirmed by the information I received in consequence of Captain Colnett's visit to these islands.

† A misprint for Albemarle in both editions.

‡ The position of Christopher's Point (Punta Cristobal) is lat. 54' S, long. 91° 31' W (268° 29' E).

From these conclusions, all the objects I had in view in steering this south-eastwardly course from Monterrey appeared to have been accomplished; since I had not entertained the most distant intention of stopping, to make surveys or correct examinations of any island we might see. But as the situation of those which were lying not far out of our track had been variously represented, I anxiously wished to obtain such information as would place this matter out of all displute for the future; and having been enabled to effect this purpose to my satisfaction, it was some recompence for the very irksome and tedious passage we had experienced in consequene of the light baffling winds that had constantly attended us after we had passed cape Corientes; since which time, to our station this day at noon, our progress upon an average had not been more than at the rate of 10 leagues per day.

I shall now proceed to state, what little more occurred to my knowledge or observation respecting that part of the Gallipagos islands that we were now about to leave. The climate appeared to be singularly temperate for an equatorial country. Since our departure from the island of Cocos the mercury in the thermometer had seldom risen above 78, and for the three preceding days it had mostly been between the 74th and 76th degree; the atmosphere felt light and exhilarating, and the wind which came chiefly from the southern quarter was very cool and refreshing. The shores appeared to be steep and bold, free from shoals or hidden dangers; some riplings were observed, which at first were supposed to be occasioned by the former, but as soundings were not gained when we were in them, these riplings were attributed to the meeting of currents. The lofty mountains of which this land is principally composed, excepting that which forms its north-western part, appeared to us in general to descend with much regularity from a nearby flat or table summit, and to terminate at the base in projecting points on very low level land; so that, at a distance, each of these mountains appeared to form a distinct island.

This circumstance may probably have given rise to the different statements of former visitors concerning the number of this group of islands; all of them however agree in their affording great stores of refreshment in the land and sea turtles, in an abundance of most excellent fish of several sorts, and in great numbers of wild fowl. Our having seen but few turtles whilst in the neighbourhood of these islands, is no proof that these animals do not resort thither;† for in the sea we saw neither seals nor penguins, yet the shores were in a manner covered with them; and in addition to this, the parts of the coast that were presented to our view consisted principally of a broken, rugged, rocky substance, not easily accessible to the sea turtle, which most commonly, and particularly for the purpose of depositing its eggs, resorts to sandy beaches. With respect to fish, we had ample proof of their abundance, and of the ease with which they are to be taken; but in regard of that great desideratum, fresh water, some assert that the islands afford large streams, and even rivers; whilst others state them to possess only a very scanty portion, or to be nearly destitute of it.‡ This however is but of little importance, as, from their vicinity to the Cocos, where perpetual springs seem to water every part of the island, vessels standing in need of a supply, may easily procure a sufficient quantity for all purposes; and since we saw in their neighbourhood many whales which we conceived to be of the smermaceti kind, it is not unlikely that these shores may become places of desirable resort to adventurers engaged in taking those animals. Notwithstanding that our visit did not afford an opportunity for discovering the most eligible places to which vessels might repair; it nevertheless, by ascertaing the actual situation of the western side of the group, has rendered the task of procuring such information more easy to those, who may wish to benefit by the advantages these islands may be found to furnish.

† Menzies remarked: “We saw neither Turtles nor Tortoise on shore, nor no place indeed where the former were likely to land on, though the neighbouring sea abounded with them, as well as crowds of Porpoises and Spermaceti Whales.”—February 7. None of the shore party saw any of the giant tortoises for which the Galapagos became famous and from which they derived their name. This was because the tortoises avoided the dry and barren lower levels of Albemarle (Isabela) Island, upon which Menzies remarked. They lived much higher up, among the volcanoes, where water collects in ponds during the rainy season. Most of the surviving tortoises now live on Albemarle. Very numerous when the Galapagos were discovered, they were all but exterminated during the next century since they “proved to be an ideal source of shipboard provender in those days of no refrigeration, living for months without food or water and providing fresh meat which was widely praised. After keeping the animals on deck for a few days while they ‘emptied their bowels,’ the animals were frequently stowed below-decks like so many casks, being brought up for slaughter as required.”—John D. Hendrickson, “The Galápagos Tortoises,” in Robert Bowman (ed.), The Galápagos: proceedings of a symposia [sic] of the Galápagos international scientific project (Berkeley, 1966), p. 253

‡ The latter is the case. Fresh water for the inhabitants is now brought in by tanker.

I shall now take my leave of the Gallipagos islands, and with them also of the North Pacific Ocean, in which we had passed the last three years.