Take Me to Your Mirador

John Woram

Among the many Galápagos visitor sites, a relatively new one is the “Mirador de la Baronesa,” — “The Baroness's Lookout,” named after one of the more colorful—better yet, most colorful—characters among the early 20th-century settlers. In late 1932, the self-proclaimed Baroness Eloise Bosquet de Wagner Wehrborn arrived with one “husband” and two other male companions (having mis-laid her actual husband back in Europe). As recounted by Dore Strauch and Margret Wittmer, the lady was a thorn in everyone's side until her mysterious disappearance a few years later. Today, she is remembered by the Mirador; about one mile from Isla Floreana's Post Office Bay, it is even included in the Galápagos National Park's Visitor Sites Guide, and its location appears in this Google Earth 3D view of Isla Floreana's northern coast:

This site is especially attractive because aside from its impressive scenic beauty, it has a history. It is known by letters that Baroness Eloisa von Wagner (referring to “The Galapagos Affair” by John Treherne) loved this place, where she spent several hours where she could acquire knowledge of vessels approaching the island. Within walking distance (30 m) are the ruins of what is known as the House of the Baroness [from the National Park description of the site].

Not a few Galápagos websites spin variations on this tale, as in this example (unidentified here to protect the guilty):

This location has a history. It was known to be loved by Baroness Eloisa von Wagner, where she would spent [sic] hours watching ships and acquiring knowledge of vessels approaching the island. Within walking distance (30 m) are the ruins of what is known as the House of the Baroness.

Other sites simply parrot parts of the National Park's description, which may leave sticklers for detail with a few unanswered questions, such as:

- Letters? What letters?

- How on earth did the Baroness get to her Mirador?

- If that “House of the Baroness” was really not a house of the Baroness, what was it?

- And whatever it was, where is it? Or, where was it?

For answers to all these questions, don't even bother looking up Treherne's The Galápagos Affair, for you'll find nothing in it about letters from or to the Baroness, nor does he even mention the place. And for good reason: it wasn't there at the time. But that was then, and this is now; the Mirador is a popular site, and appending “de la Baronesa” to it deserves some explanation, even if the National Park explanation bears little or no resemblance to reality.

To begin with the letters: there are none. Or to put it bluntly, there is no known record of the Baroness ever writing to anyone of her love for the place. So it's reasonably safe to conclude that the “letters” anecdote is little more than an exercise in “creative writing” by someone working on the Visitor Sites Guide.

As the Google Earth 3d view shows, overland access to the mirador is now—and was then—all but impossible, and especially so from the Baroness's actual house, quite a few miles to the southwest. She would have had to hike down to Post Office Bay, then walk along the coast to Bahía la Olla,§ then up a trail (which did not exist in her day) to the mirador—in all, a jaunt of about five miles. But even if there were a more-direct path, there would be no point in going there to indulge in a few hours of ship-watching. In those days, ships appeared over the horizon with no advance notice, and generally announced their arrival by a few blasts of a horn. Then they would anchor at Post Office Bay or off Black Beach, but never at the little beach at Bahía la Olla where the path to the mirador now begins.

§ Olla: A ceramic pot for cooking stews. The bay may have been so-named because its contour bears a superficial resemblance to such a pot.

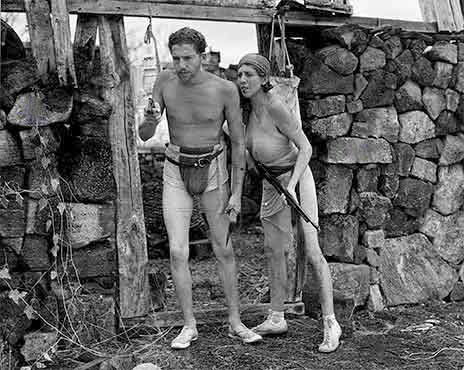

But now to further confuse the issue, there is a visual record of a stone structure and a Baroness; the latter not living at the former, but having it serve as backdrop for a “pirate film” (and a bad one at that). On the third voyage of G. Allan Hancock's Velero III in 1934, the ship called at Isla Floreana January 16-19 and 27-30. On January 29,§ film-maker Emory Johnson had the Baroness and husband-du-jour Robert Philippson done up as a piratical couple. At her urging, he marches off to shoot a just-arrived young girl (played by Ray Elliot of the Velero III). Meanwhile, the “girl's” husband shows up in search of water. The Baroness offers him some, and perhaps some other favors. But first he must perform a little chore for her. He obliges with a rifle shot that drops Philippson in his tracks.

§ The date is known from Edwin O. Palmer's Third Galapagos Trip of the Velero III (p.21):

Monday, January 29th … At 6:30 the anchor was up and the ship returned to Postoffice Bay where the Baroness and Philippson arrived at 9 a.m. and were soon off again with the photographers who had planned a scenario in which they were to figure in more or less of a pirate role. … Swett was camerman.

In other words, the Baroness and Philippson travelled overland to Post Office Bay (via an existing trail) and then the production group made its way on foot to the film site. But, how did they know of its existence? Since it's only about ½ mile northeast of Post Office Bay, chances are someone discovered it on a previous Hancock expedition, then led the way to the structure on the third voyage. His identity? Possibly, First Officer W. Charles Swett, who served as cameraman (see Palmer's account, above).

And at last we are brought close (well, close enough) to answering those final questions: if not the house of the Baroness, then what is it? (Or, what was it?) And, whatever happened to it?

The questions can be answered, in reverse order, thanks to the work of Thalia Grant and Gregory Estes. In connection with research for their Darwin In Galápagos book, the couple spent quite a bit of time on Isla Floreana, one of the four islands visited by Darwin. While there, they hiked along the shore and came upon a stone structure—again, about ½ mile northeast of Post Office Bay.§

§ Google Earth coordinates are 1°13'50.80" S, 90° 26'34.40" W (courtesy Greg Estes). Copy/paste coordinates into Google Earth search box, but unfortunately resolution is not fine enough to reveal the structure. The straight line distance to the modern “Mirador de la Baronesa” is about ¼ mile (or 370 meters) E ¾ S— perhaps double that distance on foot.

Thalia snapped several photos, and later on compared one of them with a scene in that Emory Johnson film. Both are seen here:

Left: From the Geller & Goldfine production, The Galápagos Affair: Satan Came to Eden which includes film of the Baroness and Philippson taken during the third voyage of the Velero III.

Right: 1996 photo by K. Thalia Grant (rear wall darkened here to better distinguish it from front wall).

Notwithstanding the long-gone wooden beams of 1934, the structure photographed by Thalia in 1996 is obviously the same as that seen in the film, which even then revealed that here was a “house” that had seen better days. Clearly, it was not the residence of the Baroness and her companions, nor had it been constructed as a film prop, as some have speculated. The film crew did their work in a matter of hours, and these ruins are obviously the work of many days, if not weeks. And the deterioration seen in the film suggests a structure that had been around for some years prior to 1934.

As noted above, the structure is some ¼ mile/370 meters from the present mirador site, not 30 meters as stated in the National Park description also seen above. But is there another structure near the current mirador? As a matter of fact, there is: a wooden platform recently built by the National Park to give visitors a place from which to admire the view. Its connection with the Baroness? Zero. But it is a nice story.

And that brings us back to that mis-named House of the Baroness, and its true identity. According to Grant and Estes' research, it's most likely the remains of a biological station built by, or for, the Norwegian zoologist Alf Wollebæk,§ who accompanied the Norwegian colonists who lived for a time on Isla Floreana. Here, Wollebæk studied a small sea-lion colony nearby, and years later the Galápagos sea lion, Zalophus wollebæki, was named in his honor.

§ The last three sections of Stein Hoff's Drømmen om Galapagos, Part I, describe Alf Wollebæk (seen here in sketch at right) and his work in Galápagos.

A comparison of two photographs confirms Grant/Estes' supposition: the stone hut of the pirate film is indeed the remains of Wollebæk's biological station.

Left: Alf Wollebæk's November 1925 photo of his biological station, courtesy Stein Hoff.

Right: Thalia Grant's 1996 photo, taken at the same time as her other photo shown above.

The circled areas draw attention to features that are identical in both photos.

Wollebæk's description and initials below his 1925 photo.

Conclusion: The stone hut has no connection (other than as a film prop) with the Baroness, nor with the “Mirador.” Part of the true “Casa de la Baronesa” in the highlands (not near the shore) may be seen in a 1934 photo taken on one of the Velero III voyages (photo #5; magnifying-glass icon identifies those seen in the photo). As already noted, the hut is all that remains of Wollebæk’s biological station on Peninsula Oslo Museum, just east of Post Office Bay. His station is, of course, not to be confused with Casa Matriz, the wooden house on concrete pillars built at Post Office Bay and temporarily used by various settlers.

Ainsley and Frances Conway gave their tongue-in-cheek(s) account of the eventual fate of that building (in their The Enchanted Islands, p. 178):

The remains of an old frame house [Casa Matriz, of course] were still at Post Office Bay … and remained virtually intact—except for such inconsiderable items as the inner walls, doors, windows, and flooring. Recently [ca. 1937] the Ecuadorian government had ordered this empty shell to be transported piecemeal to Isabela, for building military headquarters, but the ships had not yet got around to taking away all of it.

While waiting for the ships to get around to removing the leftovers, the Conways picked over the remains and were soon the proud owners (or at least, possessors) “… of an immense, high bed in one corner, made of siding and two-by-fours, and a table of the same.” Another table and a pair of benches soon followed, and with other settlers likewise helping themselves, in no time at all perhaps there was little or nothing worth the bother of transporting to Isabela.

Years earlier, Casa Matriz seems to have been relieved of some of its “inconsiderable items” by the Baroness and a helper. Margret Wittmer—who had taken to calling the lady “Madam” and her dwelling “the wigwam”—describes this in her unpublished What Happened on Galápagos?

Madam had started wrecking the house in the bay herself, even having wood from the floor and roof removed. This Lorenz had hid in the bushes and later carried part of it up to the wigwam.

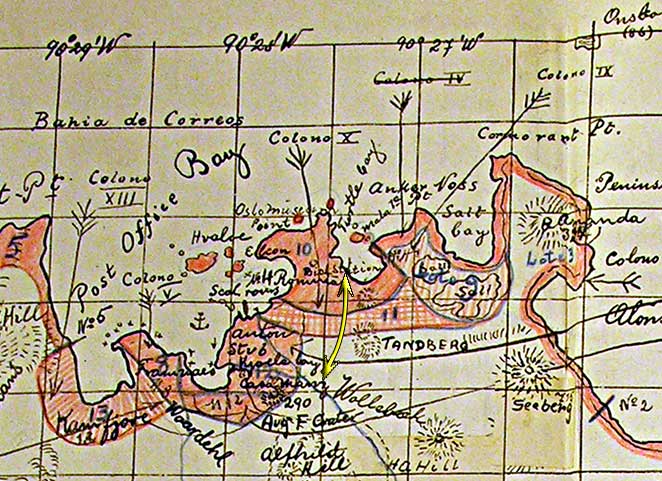

The locations of both Casa Matriz and the stone hut are indicated on a crude 1925 sketch map drawn by the Norwegian settlers August Christensen and Anton Stub, with further details given in Stein Hoff's Drømmen om Galapagos.

The above detail view from the Christensen/Stub map shows “Biol. Station” and “Casa Matriz” as indicated by the yellow arrows—not very accurate of course, but it does show the former is northeast of the latter, with the current Bahía la Olla here labeled Turtle Bay.

NOTE: Thalia Grant and Gregory Estes' Alf Wollebæk and the Galapagos Archipelago's first biological station is a definitive paper on the scientific aspects of Wollebæk's work, now available online (PDF Download) at the Aquatic Commons website (https://aquadocs.org/handle/1834/36362).