Revised Jun 12 2021/p>

← Dalrymple/Imogene Home Narratives

An account of the removal of the Pitcairn Islanders

to Norfolk Island in the year 1856.

By Geo. J. Curgenven.

An Officer of the Ship "Morayshire".

(For more information please visit the Curgenven family website George James Curgenven.)

Few of the readers of this new century have heard of the "Mutiny of H.M.S. "The Bounty". None now know of the horror with which the details were read in the Narrative of Captain Bligh — of his miraculous voyage of over 3600 miles, accomplished in 41 days, in an open boat with 18 of his officers and crew in the year 1790, and their landing at Timor. In the following year H.M.S. "Pandora" was despatched by the Government to search for the Mutineers — she visited Otaheite (now Tahiti) and there found 14 of the crew of the Bounty and after making a fruitless search for the remaining nine, who had sailed from Otaheite in the Bounty for some unknown island, she sailed for England. Those brought home were tried by Court Martial and four of them, who took an active part in the seizure of the ship were found guilty and shot. For twenty years from this date England was too much occupied in the wars with France and Spain to send another ship to the Pacific in search of the Mutineers, and the mutiny was almost forgotten in the troublous times of war.

In 1808 the "Topaz" of Boston, Captain Folger, called at the Island of Pitcairn in the South Pacific and discovered there one men with several women and children, the remnant and offspring of the Mutineers of the Bounty. The log of the Topaz giving particulars of the visit was in the possession of Captain Folger's son, Mr. Robert H. Folger, a lawyer, living at Massillion, Ohio.

This being reported to the British Government, it was decided at the close of the War in 1814, to dispatch two vessels of the Pacific fleet to discover the truth of the American report, and the fate of the Mutineers. Consequently in September 1814, H.M. Ships "Britain" and "Tagus" visited the Island of Pitcairn, which lay S.E. of Otaheite about 340 miles*.

* [Actually, about 1,348 miles.]

Sir Thomas Staines found the numbers on the island to be 40. He learnt that the Bounty was run on the rocks and burnt in 1790 — that in 1793 five of the Mutineers, including Christian; the leader of the Mutiny, were killed by the 6 Tahitian men they took with them to be their servants, out of jealousy over their wives. The same year all the Tahitian men were killed, some by their companions, the rest by the remaining four Englishmen. In 1798 M'Coy distilled spirit from the Ti-root and the following year he cast himself off the rocks in a fit of delirium, and was killed. The next year Quintal threatened to kill the two others, they therefore slew him with an axe. Young died in 1800 of Asthma; and Alexander Smith, now calling himself John Adams, was left alone with all the women and children. Thus all but two of the 9 mutineers met with premature and violent deaths. John Adams educated the children, and taught them religion and morality from the Bible which was the only book saved from the Bounty, and he died in 1829.

Of the 16 remaining at Otaheite, 2 were murdered in Otaheite, 4 were drowned in irons when the Pandora was wrecked on her homeward voyage. Of the 10 who reached England, 4 were executed, 3 were condemned to death but pardoned, and 4 were acquitted. In consequence of this mutiny 18 of the 26 mutineers met with violent and premature deaths; 30 of the crew of the Pandora were drowned and two of H.M. Ships were lost.

All the details of the Munity of the Bounty and the subsequent history of the Mutineers and their descendants are published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge "Pitcairn, the Island the People and the Pastor". In another book published by N. Jegg "The Mutiny and piratical seizure of HMS Bounty", relates the loss of the "Pandora" and the trial of the prisoners.

By 1831 the inhabitants of the island had increased so much that the Government decided to remove them to Tahiti. This was done but before the end of the year they all returned again to their island home, the immorality of the Tahitians being repulsive to them. In 1850 again efforts were made to induce them to migrate to a larger island. But it was not until 1856 that the migration was accomplished. The majority of the Islanders were anxious to be moved to a larger island for they had suffered from scarcity and dreaded a famine, and they appealed to the Government in 1853. In the next year the Government gave directions for the removal of all the convicts from Norfolk Island to Tasmania, leaving on the island all buildings, stocks, implements, etc. for the use of the Pitcairners.

Now the work in which I took an active and interesting part commenced.

The ship Morayshire, Captain Mathers, in which I was one of the officers, was chartered to remove the Pitcairn islanders with all their effects to Norfolk Island. We loaded up with Government stores at Sydney for Norfolk Island. From there we were to go to Pitcairn, bring the islanders back to Norfolk Island and then take the four remaining convicts and officers; who had been left in charge of the island, to Hobart.

Mar 18, 1856

Apr 23, 1856

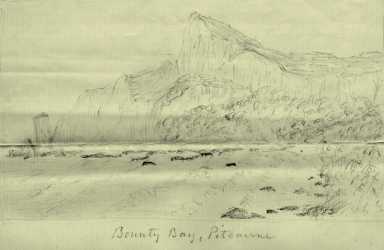

Before sailing from Sydney we took on board a Botanist, a gardener, a gentleman volunteer and Lieut. Gregorie of H.M.S. "Juno". We sailed on February 23rd 1856, and after encountering head winds and calms, more than usual, we arrived at Norfolk Island on the 18th March. The island is about 20 miles in circumference with an average width of 5 miles. It is beautifully diversified with hills and dales and the lower lands are extremely fertile. We found growing on some cultivated spots of ground, pine apples, figs, lemons; Cape Gooseberries, Guavas, Pomegranates, Bananas, peaches, grapes, straw-berries, apples, quinces, chillies and other fruits, also potatoes, cabbages, peas and beans — cinnamon and other spices, tobacco arrow-root and sweet potatoes — Maize, barley, wheat, and rye grow on the higher land. The botanist was delighted with the island and on his return voyage he was going to secure some Norfolk island Pines (Auracaria excelsa) and other native plants for which he had brought glass cases of the Ward pattern. Having landed the stores for those on the island we sailed the following day. Again head winds delayed us and we were obliged to sail around the southern end of New Zealand to get fair wind for Pitcairn, which, after encountering a storm that lasted four days, we reached on the 23rd of April<. From a distance it looked like a mere rock in mid-ocean with no other land to be seen.

On arriving near Bounty Bay we saw a small canoe with two men paddling towards us. Coming alongside they sprang on board and shook hands with all of us as if we were old friends. Their canoe was easily hauled on board by one man. I expressed my astonishment at their coming through the surf in so small a boat, but they told me that they could come through the surf in that when they dare not venture with a whale boat. As there was no anchorage we had to stand off the island the following night. The next day I went on shore in the whaleboat and the stout islanders took us safely through the surf which I found to be much as I have seen it on the north coast of Cornwall, when the Atlantic swell is rolling in over the yellow sands.

The islanders were delighted to see us and we were received with such demonstrations of affection as if we had been their dearest friends. Accompanied by two of the men I went up to what they called their town, which was composed of a good many one and two stories huts built of the Meero wood and thatched with palm leaves, the floor being raised a little above the ground level. The entrance door opens into the living room, out of which opens two or three other rooms used as bed or bunk rooms and store. In other huts the upper story is reached by a ladder from the living room. In some of the houses they slept in bunks built in the sides of the rooms having sliding panels, which are kept closed during the day, but in others they had bedsteads. There was no glass in their windows — they had sliding shutters which were closed at night and in bad weather. Simon Young took me to his hut and there I found his wife, Jemima*, busy ironing and getting ready to pack up. After eating some delicious bananas he gave me, I went off to explore the island. Walking up a small valley I found, at a brook, three or four women washing their clothes — in fact a grand wash was going on previous to packing up. I noticed the Banyan tree growing here, sending its long tendril roots from the branches to the ground. There were plenty of food-producing trees and plants, cocoanut trees, plantains, bananas, yams, sweet potatoes, Taroroot and Yappa, two arums yielding arrowroot, the Cloth tree or paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), the Tee-plant (Dracaena terminalis) from the root of which Quintal distilled a spirit, the Doodoe (Aleurites triloba) from the nuts of which they express an oil for their lamps — Mulberry and some timber trees; one as solid and dark as mahogany, which they called Meero wood and another yellow which they called lemon wood. They had also a number of fruit trees and vegetables which had been introduced, such as oranges, lemons, melons, potatoes, tobacco etc.

* [Jemima was Simon's sister, his wife was named Mary.]

I returned to Simon Young's hut, just as supper was ready, and we sat down to a savoury meal of boiled pork, sweet potatoes, yams and cooked plantains, and tea sweetened with Molasses. After supper I gave them a few tunes on an accordion that was in the house. "Cheer boys cheer" delighted them and brought an audience of outsiders.

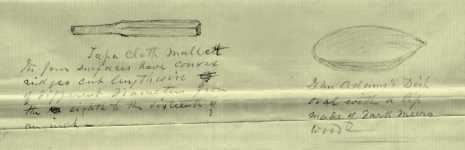

Hearing a bell ringing I was told by Simon that it was the bell of the singing room where they congregate in the evenings to sing hymns, glees and other songs. We went there and met the Captain, Mr. Robinson and Mr. Gregorie, who had been entertained by others in the village. The singing was very good, they had been taught music by means of a blackboard and chalk. The young women were all dressed in a garment extending loosely from shoulders to heels made of Tapa cloth and over this a loose short gown. We went afterwards to see them making this cloth or rather paper, from the inner bark of the paper Mulberry tree. They beat the bark with wooden mallets on a block into long strips until it is as thin as paper, these strips are then joined together by beating their overlapping edges together until the piece is wide enough to make a garment, after being dried in the sun.

The young women and girls dressed only in this long white garment with a wreath of everlasting flowers as their only head adornment. Their flowing black hair, handsome brown faces with large dark eyes, together with a natural gracefulness of movement and light cheerful dispositions made them the finest of nature's beauties. The small children were absolutely garmentless, and were as much at home in the water as on land. The men wore clothing they had obtained from the sailors who had visited the island so there was nothing to describe in their dress.

I slept at Simon Young's that night and found his bunk more comfortable than my own on board ship. In the morning I went out before breakfast, and John Evans (not a descendant of a mutineer) walked up a Cocoanut tree and threw me down some nuts, the milk of which I much enjoyed in the early morning. He took me to see John Adams's grave.

After breakfast I left my hospitable friends and was loaded with presents of Cocoa-nuts, pine apples; bananas, Oranges etc. as much as two men could carry to the boat. Jemima Young presented me also with a straw hat made by herself, adorned with two wreaths of everlastings. Before leaving the beach I asked them to show me how they used the surf-boats; so John Evans and John Quintal taking each a boat under his arm, for they are barely four feet long, dived through the breakers and swam to a rock. Waiting there until a large wave approached, they lay on their boats and floated in on the crest of the wave sliding up the beach in perfect safety. The boat is a scooped out piece of timber, which just fits the body, the legs projecting over the stern and the arms over the sides for swimming. The bow is shaped as a boat while the stern is flat and its purpose is to protect the body from injury when cast by the wave on the beach.

By the aid of the islanders we passed through the surf in the whale boat without a wetting, and the Morayshire had to stand off and on for some days until the people collected all their moveable goods; then biding a calm day, we, on May 3rd, received them all on board, old and young of all ages — 193. They brought with them several of the articles from the old Bounty — The anvil, the old gun, some of the sheet copper from her bottom, blocks and other articles. Two or three articles of interest they gave to me — John Adams's dish made of Meero wood, a Tapa mallet made of a Whale's tooth, some of the Tapa cloth, a work-box made by George Young, a son of the mutineer, and some of the girls gave me their wreaths.

Tapa cloth mallet - John Adams dish

These articles were exhibited at the Royal Naval Exhibition at Chelsea a few years ago. Well, at 8 p.m. we made sail from Pitcairn amid many a sigh and many a tear, for there was not one that could say he or she was glad at leaving their long-loved island home.

It was with some difficulty that George Adams, the son of old John, could be brought on board, he said he would rather be run through with a sword.* During the first few days, most of them were ill, but during the greater part of the voyage, with the exception of two or three, they proved good sailors. On the 24th. of May, they kept the Queen's birthday as they always had done, being most loyal subjects, by putting on their best dresses and making the day as they said a holiday. They had a religious service, sang hymns and God save the Queen, after which they fired off all the guns they had with them as a royal salute. They were all very devout and had prayers three times every day with singing of hymns.

* [George Adams' granddaughter, Phoebe Cleaveline Adams, was only six months old and dangerously ill. He was terrified she would not survive the voyage. She did, but died soon after arriving in Norfolk island.]

At last on the 6th of June, after a voyage of about 3600 miles, we reached Norfolk Island and there found H.M.S. Herald, Captain Denham, awaiting us to assist in the landing. The next day, amidst heavy rain they were all landed without an accident — 194 all told, one having been born during the voyage.

As there was no harbour or safe anchorage at Norfolk Island, we had to stand off at night and haul in during the day, to disembark their goods and chattels, this took a few days after which I went on shore. Several of them were at the landing place — they were delighted to see me and I had to kiss all the women, for if I did not they would kiss me. They were greatly taken up with the many new things they saw, they were afraid of a horse that was near. It had on a bridle and a saddle so I got on its back and cantered off at which they screamed with fright. Coming back I induced first one man, then another, to get on its back and ride at a slow pace, and the girls with but a little persuasion, came and stroked it. The big houses and farm implements interested them very much. The land was being surveyed to be parcelled out among the several families, and until allotment and their houses were built they were to live in the barracks. This they did not like and many regrets were expressed at leaving their beloved Pitcairn.

It will not surprise the readers of this article that in 1858 Matthew* and Moses Young returned to Pitcairn with their families, 16 persons — and in 1863 twenty seven others returned, mostly descendants of Young, the mutineer, and with them returned Thursday October Christian**, the first born on the isle of Pitcairn, and his wife, also Elizabeth Young, a daughter of John Mills, whose was the fourth birth on the island, and Hannah Young, daughter of John Adams. In 1898 the population of the Island had increased to 141 and they were greatly degenerated through inter-marriage. The population in Norfolk Island had at the same time increased to about 900. The Government are again contemplating the removal of the Pitcairners.

* [Mayhew.]

** [Thursday, the first born on Pitcairn, died on Tahiti in 1831.

It was his son Thursday who returned to Pitcairn from Norfolk.]

They were a most interesting people and well deserved the motherly care of the English Government