|

THE HANGING OF THE MUTINEERS

At nine sharp a lanyard attached to a dog head was released and a flint

struck a spark into a pan which ignited a tiny pool of black powder. The

powder sizzled down a touch hole and exploded a compressed canvas bag full

of gunpowder. The ensuing explosion fired a wad noisily but harmlessly

across the water. On the same ship, as the white cannon smoke dissipated,

a yellow flag was hoisted. The yellow flag was a summons to an execution

and it demanded the attention of the whole Channel Fleet.

Pasley's crew, and every other

according to naval law, were assembled to witness the proceedings. Launches,

cutters, dingys and other assorted vessels from every ship of the channel

fleet formed a close perimeter around HMS 'Brunswick'. The battleship's

deck was crowded with officers, while all around were redcoated marines

armed with swords and bayoneted muskets, both to prevent the prisoners

escape and to keep the spectator craft at bay.

Along the shore, afloat in

ferries and pleasure boats, were men, women and children. Thousands had

come to watch. There was no thought of an event of sorrow and solemnity

this was a carnival, a spectacle, a circus. Jugglers, whores and entertainers

plied their trade on the nearby docks. Others rowed among the pleasure

boats. Picnics and hampers were unpacked and table cloths spread.

|

The captains of the fleet sat assembled around

Lord Hood on the poop deck and were served delicacies and port as they

chatted and waited the proceedings. At eleven Hood motioned to his aide

Captain Curtis for the prisoners to be summoned up. Curtis stood and gave

instructions to his marine lieutenant who disappeared below with a platoon

of redcoats.

A hush fell over the crowd

as the mutineers emerged from their darkness. They blinked as they looked

around, startled at the brightness and the noise, and size of the crowd

which in roared and shouted to each other. People strained around corners,

over heads, under awnings, to catch a sight of the condemned. People in

boats layed their hands on the shoulders of the people before then, fathers

lifted children and loved ones high in the air to get a better view, others

stood on tiptoe, upon gunwales, upon next to nothing, all trying to observe

every inch of those about to die. |

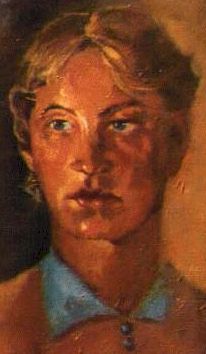

Pasley, seated with Hood and the

other captains on the poop, watched the condemned arrive. Like tired actors

about to play their final scene, he thought, but suddenly, he noted they

took their lead from Millward and they stiffened with resolve. They stepped

forward, heads up, and passed through the lines of the assembled crew to

make their way aft to the quarter deck. Like hundreds of others Pasley

gasped when he observed the bearing and proud splendour of young Tom Ellison

who smiled and waved as he walked between the two adults. Then even more

surprise when his gaze then fell on a grim trio of Graham, Morrison and

a clergyman following behind. It was the first time he had sighted Graham

since the tribunal, and in a place he least expected.

By naval regulation able and

common seamen were arranged along the deck in three columns of twenty men.

Yard ropes stretched along each line passing through each man's hands and

up to three separate block and tackle that hung and exact twelve inches

below the mizzen yard. The block and tackle were to ensure a slow and even

pull on the ropes. Two of the tackle were to port and one to starboard.

From these blocks, and reaching to five feet above the deck, were the plaited

nooses.

Some of the sailors nervously

fingered the ropes as if they were serpents instead of simple woven hemp

while others just looked at the mutineers and wondered which would step

into their particular noose.

The prisoner's separation took

place amidships with Ellison and Millward to be hanged on the port arm.

Graham went to stand behind Ellison. Except for the leg irons the chains

on all three had been removed.

As required a corporal read

out the charges and the sentence then invited last words from the condemned.

On the cat head Millward paused and motioned to Morrison who handed him

a paper. He looked at it, raised up his head, surveyed the audience. Then

in a voice that began with a falter but soon boomed out across the water

he addressed the ship's company;

"My Lords, officers and

fellow crew members. I speak for myself and for my two companions when

I say we deeply regret out part in the mutiny on HMS 'Bounty'. We

would like to apologise to the families who lost husbands and sons in the

unfortunate consequences of that event, especially those who were lost

by accident or illness. They were Thomas Leward Surgeon, David Nelson Botanist,

William Elphinstone Master's Mate, Peter Linkletter Quarter Master, Seaman

Thomas Hall, Seaman Robert Lamb and big John Norton. They did us no harm

and did not deserve to die so far from home. For that we are truly sorry.

We three common sailors that

stand before you now, were not pressed men, nor were we recruited from

prison, instead, we actively chose the life of a sailor. Yes, we were aware

of the hardships, exploitations and brutalities that lay in our path, and

we welcomed them. The reality of our life was salt sores, it was of freezing

or sweating it was of poor pay and the barren taste of ship's biscuit.

It was of hardship and the stench of bilges but it was also of mateship

and sharing. We shared hammocks and biscuit, heads and whores. We fought

and bitched and looked after one another. We have no regrets, we were well

aware of the dangers. My heart touches the many remembrances long fallen

asleep of close friends, of shared hunger, of cold and wet backs, of women,

ale and the good times. My desire then, from my youth was to see strange

countries and fashions.

Many have asked me why we mutinied

and my answer is this?ateship is our privilege, and one that the landsman

should not presume upon or quickly judge. Perhaps you should all remember

the words of Mr Garrick's song;

'Now cheer up my lads, 'tis

to glory we steer,

To add something more to this

wonderful year:

Tis to honour we call you,

as freemen not slaves,

For who are so free as the

sons of the waves?'

'Millward looked up from

his notes and a braced purpose entered his body while a kind of inspiration

shone from his eyes. It not only contradicted his manner but changed and

raised the man. He turned to the youth standing beside him, "We are

not afraid to die ... even young Tom." And he stared long at the regally

attired youth shaking his head – "and if the country will profit by

our death ..." his voice wavered and he finished quickly, "May

God forgive us all." He turned to his executioners, "we forgive

you mates, look sharp and pull hard on the ropes."

A marine whispered to Ellison

who nodded his understanding. He carefully, gratefully, unlocked the silver

clasp, shed his cloak, folded it and handed it to Graham. Then he turned

and presented his arms behind his back to the man with the binding cords.They

tied his arms and those of Milward and Burkitt. A little time was spent

in personal devotion during which Morrison performed the last officers

to Millward and Burkitt by placing the nooses over their heads. Graham

did the same for Ellison. For a while Millward and the boy stood together

and they spoke as if they were alone. Voice to voice, eye to eye, heart

to heart, like two children of the same God. Together they viewed the same

dark highway. Together they would travel it and Millward promised to lead

the way.

|

Graham stepped forward, bent

over and whispered into Ellison's ear then, taking a shoulder under each

hand, viewed him closely. The youth smiled, and in an unexpected and strange

movement leaned forward and he kissed the older man.

Graham stiffened and pushed

the youth away.

Again the cannon fired and

the long columns hauled on the ropes and the mutineers were slowly hoisted

above the crowd. The able seamen that pulled mostly looked down at their

hands where the plaited hemp shook; where they felt the struggle of life

pass along the rope?nto their hands, up their arms to lodge as part of

their memory rarely to be visited hence. They were destined to pull many

more ropes but few would feel as heavy and require so little strength.

|

The clergyman, who felt he needed

to say something. shouted out. 'So the rustling of an angel's wings blends

with the echoes of the watchers' gasps and its victims are no longer wholly

of earth but have about them that breath of heaven.'

The bodies rose further into

the air and as Ellison felt the rope tighten he held his breath. He kept

his body completely stiff and tried to control his bladder and bowel. The

concentration made him sweat, stare and bulge his eyes. It was difficult

but he knew he must try, and keep trying. If only he could hold himself

back.

Graham's stood four paces in

front of Ellison and watched his eyes. He saw the glassy concentration,

the widening of the pupils as the boy's body tried to resist the ropes

stranglehold. By the time Ellison's his feet reached Graham's eye level

Graham knew the boy was losing the battle. The limbs were twitching and

the body was beginning its involuntary spasms. The eyes grew even wider

as Ellison's alarm slid toward panic.

The crowd turned their attention

to Burkitt who had somehow managed to free his arms. Even though he was

unconscious his hands alternatively tore at his neck flayed uselessly in

the air?ut to no avail, too late.

For the next thirty minutes

most watched and felt comforted by their life ...their petty complaints

disappeared as surely as the futile struggle above would cease. As usual

some thought of having more children.

Death by strangulation with

a yard rope pulled by their comrades was the way of all naval executions.

In the end with tongues and eyes protruding the fouled bodies appeared

strangely shrunk. Nothing as quick as the French guillotine, thought Pasley,

it would have dispatched thirty in the same time?nd was currently doing

so. He wished Bligh were present... and Christian.

Graham watched as the corpses

were gently lowered to the deck. The extreme care now taken contrasted

with the roughness used before. He moved over to examine the corpse. Ellison

could as well as been asleep such was the state of the body, the look on

the face – the calm, the peace. Was it not for the rope and its impression

there were no signs of strangulation, not like the others.

The ship's surgeon mistook

the look on Graham's face, "I have heard tell of such but never observed

one Mr Graham."

"What?"

"The rope did not kill

him sir he was dead before the rope."

"Bloody nonsense."

"I have heard if the soul

wills it the heart can stop by itself," he was a man who loved superstition

and legend and was intent on producing another. He pointed down,"

just like this one 'ere. The first one I have ever seen though, remarkable!

Look at the face no burst blood vessels nothing, remarkable. Aye sir, this

one were dead before he was hung."

Graham growled and looked at

his guards as if to order himself away.

"Do you want his clothes

back?" the superstitious butcher shouted. Everyone knew that by tradition

the surgeon usually got to keep the clothes, one of the benefits of the

job.

Strangely at the mention of

the clothes something as hard as diamond suddenly cracked inside the advocate.

|