|

John Shillibeer Notes |

Patookee,

|

Contents.

|

TO THEOFFICERSOF THECorps of Royal Marines,ANDROYAL MARINE ARTILLERY,THIS WORKIS AS ASMALL TRIBUTE, OF HIS HIGH ESTEEMMOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,BY THEIRMOST OBEDIENT, AND VERY HUMBLE SERVANT,JOHN SHILLIBEER, LIEUT. R. M.WALKHAMPTON, March 17, 1817 |

PREFACE.––––ONE of the most ordinary features of a prefatory address being that of propitiating the public opinion, the writer of the following pages ventures on this part of his task with a persuasion, that in few cases could the liberality of the reader be more required, or perhaps more justified, than on the present occasion. The motives for committing the following Narrative to the press, were not such as usually actuate adventurers in the paths of Literature. Certainly neither the calculation of interest nor the hope of reputation propelled the author to his undertaking. The too frequently recorded disappointments of those who, uninitiated in the mysteries of the press, presume to look to it for indemnity for their labours, prevent his indulging in a similar delusion, and he is too |

conscious of his deficiencies, to entertain the most distant hope of distinction by his present humble performance. The motive, then, to be explained, is simply that of complying with the solicitations of many of his friends, the companions of his voyage, who, relying on the fidelity of his observations, wish to preserve a narrative of those events in which their feelings were equally interested with his own. This, mingled with a faint hope that, in some particulars, the circumstances described will not be entirely without interest to the public, have led to the production of this volume. The illustrations will, perhaps, have their best apology in the fact of their having been executed by the author for his amusement, and in their being the first productions of his attempts at graphic delineation. Of the style and phraseology of his work, he is fully sensible how much he stands in need of every indulgent consideration. A life of arduous duty, within the confines of a ship, admits of little opportunity of acquiring either grace of composi- |

tion or accuracy of language. The writer is perfectly aware how vulnerable he is to criticism on this ground; but there is one consideration which may redeem this humble performance from the obloquy to which it might otherwise be exposed, and this he presents to the reader, in the solemn pledge, that whatever may be the defects of his performance, the want of truth will, in no instance, be found to augment the literary delinquencies of which he may be found guilty. |

|

The Names of Officers belonging to the Briton of 44 Guns and 300 Men.

|

A NARRATIVEOF THEBRITON'S VOYAGE,T0PITCAIRN'S ISLAND.CHAPTER I.Notwithstanding the variety of publications which have at different times appeared on this subject, I feel it is impossible that a voyage to the South Seas can, under any circumstance, be devoid of interest, and as a more than ordinary share has been attached to the one so recently completed by H. M. Frigate Briton, I have, at the solicitation of my friends, been induced to submit to the notice of the public, the observations which occurred to me during the period of my employment on that service. |

December 31, 1813. It was late in the month of December when the Fleet destined for the East Indies and South America had collected at Spithead, and the Commodore availing himself of the first easterly breeze, proceeded without tarrying at St. Helena, into the English Channel. In a few days we had cleared the western promontory of England, and early on the morning of the 25th day from our departure, we made the island of Madeira. During the two preceding days it had blown with exceeding great violence, nor was the wind abated when the Fort William Indiaman became disabled and in want of immediate assistance, which occasioned our separation from the Fleet, and ultimate change of destination. It was two days 'ere we could reach the anchorage of Funchall, when all our mechanics were set to work, and from the most exemplary exertions of Sir Thomas Staines, we were on the eighth day again enabled to put to sea. At our approach to this anchorage, I was very much pleased with the appearance of the town, as well as with the beauties of the scenery, which, altho' in the depth of winter, bore a very agreeable aspect. Funchall, the capital of the Island, in latitude 32° 37" N. and longitude, 16° 15" W. is |

situated on the side of a steep mountain; forming a kind of amphitheatre, prettily interspersed with vines and trees of various sorts with which the Island abounds. It is of considerable extent, and rather regularly built, the streets narrow, but from a constant run of water thro' many of them, they are comparatively clean. The inclination of this mountain gives the houses at the upper part of the town, an extensive view, not only of the beach below, but also of the adjacent Islands, known by the name of the Deserters. The rivers running thro' the town, are at some periods of considerable size, and principally supplied from the snow, which, during the greater part of the year, clothes the summits of the mountains, from whence they issue, and run with a rapidity, impeded alone by the massive rocks with which their courses abound, until they discharge themselves into the sea. The fortifications are but few and of little import, and the troops which occupied them, were part of the English Veteran Battalions. The town possesses several churches, but none of them are handsome, and with the exception of a massive pair of silver gates in front of one of the altars, there is nothing worthy of notice. |

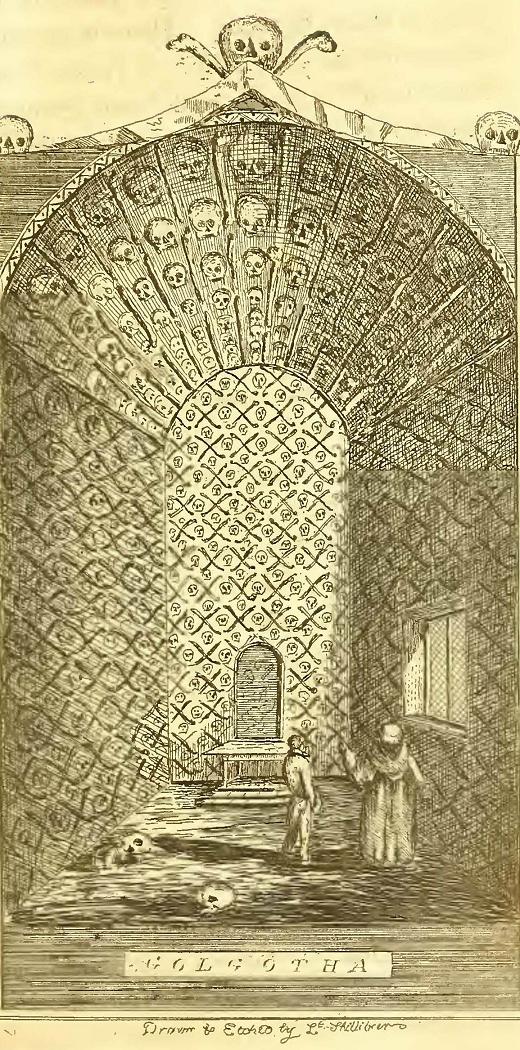

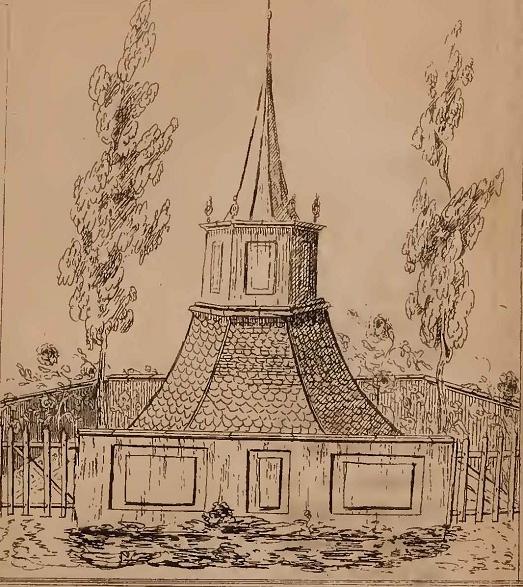

I did not perceive a painting of any merit in either of them. There is an extensive college for the instruction of youth, in all the branches of literature, and I was given to understand a great many young gentlemen are sent here from Portugal, to receive their education. There is a dominican and a benedictine monastery, and to the latter (which is the only thing curious or worthy the notice of a stranger) is attached a small chapel formerly known by the name of the chapel of "All Souls," and had for its motto "memento mori," but it is now better known by that of Golgotha, which appellation it has obtained from its being entirely lined with human skulls and bones. Its interior has no other tracery. Of its origin I could only learn, that it was founded by some religious persons, who at their death bequeathed property to a considerable amount, on condition that a certain number of masses should be daily said for the repose of their souls, under the penalty of losing such bequests in case of the slightest neglect; but notwithstanding this precaution, the chapel has not for many years, been used for any other purpose than to gratify the curiosity of the traveller, nor could I ascertain that the masses were continued to be said in any other place, altho' the Priests still continue to receive the benefit arising from the estates so bequeathed. In this horrible sanctuary, the conductor stalls the attention of the stranger to the skull of a man who, in consequence of having a lock jaw, had four of his front teeth drawn, and being fed through the aperture, his life was preserved to a very great age. This skull was in the highest state of preservation. |

Golgotha |

The climate is particularly fine, insomuch that Funchall and its vicinity is frequently the resort of invalids; but few, I fear, have sufficient resolution to withstand either the temptation of its natural luxuries, or the hospitality of its Anglo inhabitants, and reap the full benefit of its renovating salubrity. The invalid can avail himself of a temperature the most suited to his immediate complaint, by being carried up or down the mountain he is also enabled to enjoy the most delicious fruits, and not only those natural to the Island, but of his own country. The "scenery of this Island is peculiarly romantic—precipices of stupendous height, covered with most delightful foliage, here and there interspersed with huts, and cataracts precipitating from rock to rock. in awful grandeur, until Meeting from various directions among the trees and cottages at the bottom, they form one general stream, which roars as it put.- sues its course to the town. The, chapel on the mount, stands in a most beautiful situation, but possesses nothing worthy of notice, except the loveliness of its site, which affords a view as delightful as can possibly be conceived; and although the journey to it is tiresome, the stranger will be fully repaid |

for his labor by making it a visit. The priest who lives adjoining the chapel, I found to be a very intelligent man, and he treated me with great civility. The inns, whether Portuguese or English, are much below mediocrity, and notwithstanding the little accommodation and abundance of filth, , their charges are enormous; and to make the latter still more grievous, the English one pound bank note, was then only current at fourteen shillings. I was greatly surprised at finding the theatre so good: it is handsome, spacious, and in every respect convenient. It was built a few years ago by subscription, and the most considerable contribution was made by the English merchants residing there, which may in some measure account for its being both in the English style, and equal in beauty to any of our provincial theatres. About this period one of the most zealous of the English residents proposed the erection of a protestant church, and from the place of amusement having been reared with the rapidity of a meteor, he calculated on a liberal support; but so few persons came forward on this occasion, that the project was relinquished and the few donations returned to the donors. This has been a subject of some mirth to the Portuguese. |

Little, independent of wine, is produced in the Island, so that the vine is every where cultivated with the greatest care. Not a spot however rugged, but is turned to advantage. There are a great many slaves here, who are ' treated less cruelly than in most of the Portuguese settlements. They are seldom allowed more clothing than a coarse rag tied round their middle. On the Fort William being in readiness to proceed, we weighed anchor, put again to sea, And after passing through the Cape de Verde islands and a voyage of little interest, we arrived at Rio de Janeiro. |

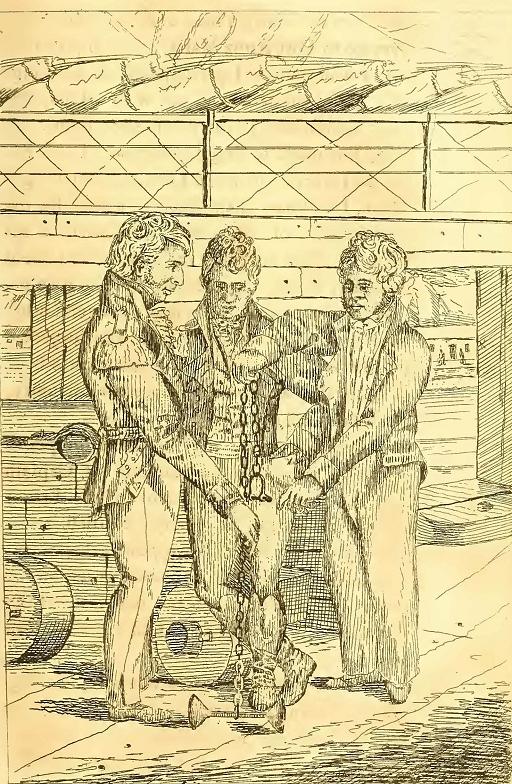

CHAPTER II.On the evening of the 20th of March, we intered[sic] the harbour of Rio de Janiero, where we found Vice-Admiral Dixon with a small English force. Early next morning the, Portuguese flag was saluted, which compliment was acknowledged by a small battery on the island of Cobrus.* * In one of the dungeons of this island, it is said there is at this moment confined a subject of Great Britain, and that Lord Strangford and Sir Sidney Smith have used every measure to effect his liberation, but to no purpose. The report runs thus; – that about three years prior to the Portuguese court being removed to this place, an English sailor in a state of intoxication happened to be in the streets of Lisbon, when the procession of the Host was passing, and from ignorance did not follow the example of the Portuguese in falling on his knees. A friar endeavoured to enforce it, when the sailor fancying himself attacked, gave battle, and the holy gentleman was soon laid prostrate. Our countryman was overpowered, committed, tried, and condemned; but by the humanity at all times so conspicuous in Catholic countries, his sentence of death was commuted for perpetual confinement in a dungeon, and when the court moved from Lisbon, he also was put on board one of their ships, and conveyed to Rio Janiero where he now lingers out a miserable existence. If this story be true, and I have heard it confidently asserted to be so, this unfortunate young man has been for a long series of years, a most melancholy victim to the unrelenting and unparalleled tyranny of a government which owes its very existence to that of his own country!!! |

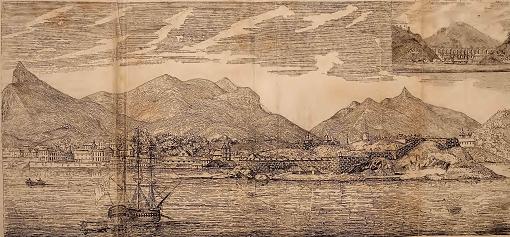

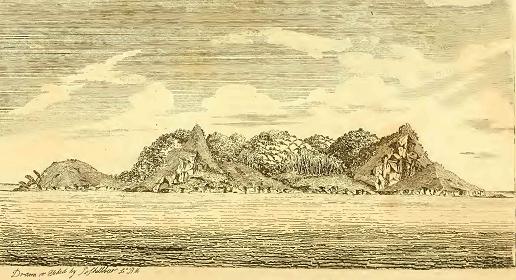

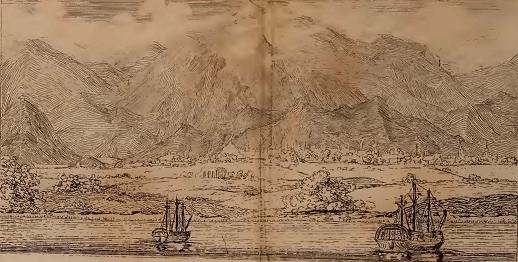

A View of the City of San Sebastian, Isld of Cobrus, Rio de Janiero;

|

The city of San Sebastian, the capital of the Portuguese dominions in South America, and residence of the Prince Regent, is situated. on the south side of an extensive harbour; whose entrance is so exceedingly narrow and well fortified by nature, that with the smallest assistance of art it could be rendered impregnable against any attack from the sea. The fort of Santa Cruz, and a very remarkable mountain, from its shape bearing the name of the Sugar Loaf, form the entrance, at the distance of about a mile. There is a bar which runs across, but the water is at all times sufficiently deep to allow the largest ship to pass. Santa Cruz may be considered the principal fortification, and is, with the exception of two small islands commanding the channel, the only one in a tolerable state Of defence. At the foot of the sugar loaf mountain, is a battery of considerable extent, but so neglected, like several others along the shore, that it is almost become useless. The city derives but little protection from its immediate fortifications, and the island of Cobrus, notwithstanding its contiguity,is now but little calculated to render it any. There are wharfs and stairs for the purpose of landing at, but the most convenient is at the great square, in which the Prince resides. The palace was originally the mansion of a |

merchant: it is extensive, but has nothing particularly magnificent in its appearance, to indicate its being the royal residence of the illustrious house of Braganza. At the bottom of this square, is a very good fountain, which is supplied with water from the adjacent mountains, and conveyed some distance by the means of an aqueduct. The water is not good, and on first using it, causes a swelling accompanied with pain in the abdomen. Ships may be supplied with considerable expedition. It is almost impossible for it person possessing the least reflection, to pass this spot without being struck by the contrast, which must necessarily present itself to him. – On the one hand, he may contemplate the palace of a voluptuous prince, surrounded by courtiers and wallowing in luxury, on the other, slavery in its most refined and horrible state. Leaving the square, you enter a street of considerable length and width, in which the custom bouse, the residence of the British consul, &c. &c. are situated. The houses are generally well built, some of the streets are good, and all exceedingly filthy. The shops are well supplied with British as well as other wares, and whether the vender be English or Portuguese, he is equally uncon- |

sionable in his demand. Most of the streets are designated by the trades which occupy them. – As in Shoe-street, you will find shoe makers; in Tin-street, tin men; in Gold-street, goldsmiths, lapidaries, &c. – Gold-street is the chief attraction, and is generally the resort of strangers, who are anxious to supply themselves with jewellery or precious stones natural to the country: but it is not always they are fortunate enough to succeed in getting them real, for since it has become the royal residence, it has drawn such a host of English, Irish, and Scotch adventurers, and the Portuguese being such apt scholars in knavery, that among them it is ten to one you are offered a piece of paste for a diamond, – among the former it is but seldom otherwise. The Inns, although better than in many places, can boast of no excellence. This city possesses a considerable number of churches, but they are by no means splendid, and excepting in the Chapel Royal, which is adjoining the palace, I observed nothing worthy of notice. Here may be seen a few good portraits of the Apostles. The altar piece is modern, and contains the full length figures of the prince and family kneeling before the holy virgin. The theatre and opera are attached also to the palace, but possess no particular elegance. The market is well supplied with every article, and |

is in so eligible a situation, that with a comparatively small portion of trouble, it might be kept in fine order: but the people are idolaters to filthiness, and not less slaves to it than to superstition. The laws of this place seem to be very deficient; without money it is impossible to obtain justice, and with it you can prevent its being administered. The murder of a lay-subject is scarcely ever punished; the least insult to the church, most rigorously. The trade with this port is very considerable, and from various countries. There is a Chinese warehouse of great extent, and at certain periods, articles from China may be procured at a low rate. This establishment is propagating with the greatest assiduity the Tea-plant, and from the progress they have already made, I am authorised in drawing a conclusion of its ultimately being of so great importance to Europe, that instead of China, the Brazils will be the grand mart for this dearly beloved article. The country for a considerable distance round, is peculiarly beautiful; the mountains high and woody; the vallies perfect gardens; fruits of the most delicious nature are found here in great abundance, and the orange appears to be a never failing tree; the quantity |

of this fruit I have seen exhibited for sale, in the orange market is astonishing, and on the same tree is often to be seen, the blossoms, the fruit in its primitive state, some half ripe, and others fit for use. The pine apple is also here, and in great perfection. In the neighbourhood there are several botanical gardens, chiefly belonging to private individuals. Many plants but rarely to be met with in England, were brought from them in the Briton. The naval department of the Portuguese is not great, but they had commissioned several sail of the line, and 'ere we left the port five of them with some frigates and corvettes were ready for sea, – Many others of various classes were moored off the arsenal, which is of some extent, and situated near the Island of Cobras. The harbour of Rio de Janeiro is spacious, and was the heat less oppressive, it might be esteemed as one of the most desirable in the world. There is a breeze from the sea generally about noon, which, cools the atmosphere and renders it in some degree bearable. Notwithstanding the entrance is so narrow, the harbour increases to the width of three or four leagues, in which gulf or basin are numerous small islands, some of them possessing villages, others gentlemen's seats only. The water becomes soon shallow, so that at a small |

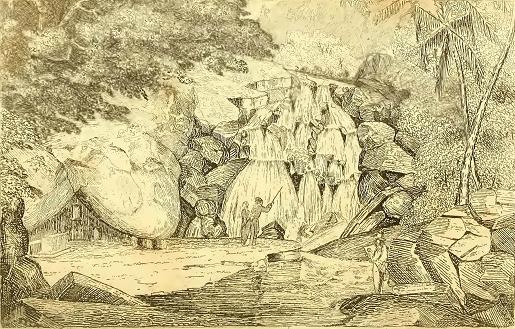

distance above the island containing the British Hospital, it is not sufficiently deep for a vessel of any burden to pass: but great trade is carried on by means of large boats. The whole of those islands are very picturesque. The district of Braganza situated immediately opposite the city of St. Sebastian, is also very fine, possessing the small town of Braganza and a few villages along the coast. Sir S. Smith has here an estate of considerable extent, which was presented him by the Prince Regent in compliment for the services he had rendered him. The water-fall at Tajuca is about eleven miles from the city, and is worthy the notice of a traveller. The fall is not perpendicular, but broken by massive rocks which project, and which add greatly to its beauty. The scenery around it is romantic and wild, and until you come to the very spot, the noise of the water is the only indication of your being near it. It is about sixty feet high. On the left hand of the entrance to this place, is a massive and overhanging rock, supported only by three small stones, and where are deposited the remains of a monk belonging to one of the monasteries at the city, who in his life conceived so great a partiality for this spot, that be requested to be buried there when dead. |

A View of Tajuca Waterfall |

The tomb is oblong, built of bricks, with two steps leading to it, – bearing no inscription, but is covered with the names of those people who have been there. Under this place there is a seat for the accommodation of visitors, and also two niches, but for what purpose they were placed there, I could not ascertain, altho' they evidently appear to have been intended to receive a Bust, Urn, or something of that nature. The inhuman and barbarous traffic of slaves, is carried on to the greatest extent it is possible to be imagined, and as the immediate and private revenue of the Crown, would receive a severe shock by the abolition of so unnatural a barter, there can be, I fear, but little hopes of so desirable an object being speedily effected, without the humanity of the European states turning their recommendations into commands, and enforcing compliance, which I am persuaded would be the case were the different legislators but faintly impressed with the horrors that constantly occur at this place, and the barbarity to which those unhappy people are hourly subjected. – The labour let it be ever so laborious, is performed by slaves, and it is seldom there are more than six apportioned to the heaviest burdens. I have frequently seen as few as four groaning under |

the weight of a pipe of wine, which they have had to remove through the town. Many of those poor creatures are bred to trades, and are sent out daily or weekly by their masters with orders to bring him a certain sum at the expiration of that time, and what they can get over they may consider their own: but they are always so highly rated, that it is with the greatest difficulty they can raise the sum nominated; and in case of defalcation, it is attributed to a want of exertion, or laziness, which subjects the unhappy victim to punishment for a crime, the master alone has committed. Nothing can be more common than instances of this nature, and as the following was related to me by a respectable British merchant, I can rely on its veracity: – "A man," said he, "possessing a few slaves may be considered of good property, particularly, if he bought them when young and has brought them up to trades. With a man of this kind I am acquainted, who is as barbarous and remorseless a wretch as can be conceived, he has several slaves, and as they have all been taught some trade or other, he sends them forth to earn, according to their occupations, certain sums and their food, which must be completed under a penalty (which is seldom remitted even to the most industrious or lucky) of a severe |

flogging. One of those (continued he) was a barber, and for a considerable period shaved me every morning: he was a quiet man, and of great industry, and, as far as came under my observation, always on the alert for his master's interest. For several days I observed he bore a gloomy and melancholy appearance. I asked him the reason, and was informed he had been unsuccessful, and could not render to his master the sum required; that he had little hopes of being able to raise it, and as little doubt of being punished. I gave him something towards it. When he came again, he informed me, that out of thirteen or fourteen, he alone had escaped the lash; but, if he did not make up the deficiency, his would be of greater severity, than had been inflicted on his companions. As the time approached when he must render to his master an account, he became greatly distressed, and despaired of accomplishing his promise. He went with tears in his eyes, tendered what he had gained, and assured him of having used every means to raise the specific sum, and implored a remission of punishment, or a suspension until the following Monday, which at length was granted him, but not without threats of many additional stripes in case of failure. The time fast approached, |

when he must return. He was still deficient. He reached the door of his master's house, when, in despair of being forgiven, and dreading the ordeal he had to undergo, he took from his pocket a razor, and with a desperate hand nearly severed his head from his body. I saw him, several days after, lying in this mangled state near the place where he had perpetrated it. This horrid deed had no other effect on the master, than to increase his severity towards the others, on whom he imposed heavier burthens, to recompense him for the loss he had so recently sustained. I enquired the cause of so many slaves lying dead in the streets, and was assured, that when they were ill and thought past recovery, they were disowned by their masters, to evade the expenses of a funeral, and thrown out of doors, when their miserable lives were soon brought to as miserable a termination. When any of these bodies are found, (which constantly occurs,) there is a soldier placed over it with a box, nor is the corpse removed from the spot, until a sufficient sum has been left by the passengers to defray the expenses attendant on the interment. I witnessed several instances of this nature during the period we lay in the harbour. The cruelties these unhappy people are subjected to, is more calcu- |

lated to fill a volume, than to be brought within the narrow compass of so small a work as this; and, I am sorry, to say, the Europeans, of whatever nation, instead of setting a humane example to wretches whose hearts had been long callous to every feeling of sensibility, vie with each other in minutely imitating their unfeeling conduct. On the 28th of March, every thing being ready for sea, we expected to sail with our charge; but some intelligence of importance having been received from the Pacific Ocean, the Fort William was detained, and we, instead of doubling the Cape of Good Hope, were ordered into the colder region of Cape Horn, round which I shall hope to lead the reader early in the next chapter. |

CHAPTER III.All communication with the shore having ceased, we discovered the object of our voyage to the South Sea, to be the United States frigate Essex, which had done considerable injury to our whale-fishery, and was then, according to the best information, refitting in the port of Valparaiso. From the season being so far advanced, we had every reason to anticipate an inclement and boisterous passage round Cape Horn; but, by the pleasing hope at all times so fondly cherished by British sailors, of gaining glory in so remote a region, the storms were conquered before they came, and in imagination we were already at the entrance of the wished-for port. The wind from the south-east, which may be almost deemed periodical, had commenced, which greatly prolonged our voyage, insomuch that it was not before the 3d of May we got into 62° 33' south latitude, when a strong breeze from the pole soon wafted us by the inhospitable shores of Terra del Fuego to the coast of Chili. It will be hardly ne- |

cessary for me to inform the reader, that in so high a latitude we found the cold excessive, and the weather tempestuous. Thermometer at 23°. During the whole of the 2d, the wind blew with such violence, that we found it impossible to set the smallest sail; and the sea bore a more terrific appearance than I had ever before seen, or wish again to witness. We did not see any ice, nor had we any snow subsequent to passing the coast of Patagonia; but rain in abundance, and, unfortunately, the men were badly supplied with warm clothing, which occasioned in the sick-list a frightful augmentation. As we proceeded to the southward, the common sea-gull became scarce; and before we reached the latitude of the Falkland Islands, they had wholly disappeared, and were succeeded by birds of beauteous plumage, called by navigators "Pigeon de mer." Those increased in number as we approached the pole, and left us again in the Pacific Ocean, when they were replaced by a species considerably larger, and quite black. About the latitude of 43° south, we were joined by some albatrosses of great size, but they did not continue with us long. We made the land near the island of Chiloe, and, after passing the island of Mocho, and experiencing variable winds, arrived at Valpa- |

raiso on the 21st of May, where we found the object of our pursuit a prize to his Majesty's ships, the Phoebe and Cherub, and preparing to sail for England. The Tagus was also there. Our men, from so long a passage, and being so much exposed, added to the great want of warm clothing, were become very sickly, insomuch that the surgeon's list was increased to 109; but, being abundantly supplied with every species of provision, and the most marked attention being paid to their comfort, it was soon reduced to a comparatively small number. Thermometer from 48° to 59°. Our refit was hastened as much as possible; and on the 10th day from our arrival, after taking on board a number of the Loyalist party, who had been prisoners in Chili, we sailed in company with the Phoebe, her prize, and the Tagus: the two former being bound round Cape Horn, we parted from there off the island of Juan Fernandez, and proceeded, in company with the Tagus, to Callao, the port of Lima, where we arrived in fourteen days, and had ten days' relaxation. During this period, we received frequent visits from the Limanians, who are passionately fond of aquatic excursions, and shew great interest when the object in view is a British man of war. On our part, we |

made frequent parties to the great city, and to an eminent degree experienced the hospitality of its inhabitants. The ladies being pretty, and possessing a more than ordinary share of interesting vivacity, we were led so imperceptibly to the period of departure, that it had arrived 'ere we could have hoped it had half elapsed. Thermometer from 64° to 68° (on board); on shore at 80°. I am aware it may be expected I should here give some account of this famous city, and I should do so, had we not returned to it again, when I had a greater opportunity, not only of making personal observations, but of collecting a great many materials necessary for that purpose: I shall therefore crave the indulgence of postponing it for a while, and in the interim I will take a brief view of the ports we touched at along the coast, as well as the Gallipago Islands. Leaving the anchorage of Callao, (June 26,) and sailing along the coast, which at times presented a pleasing or dreary aspect, according as it became more or less cultivated or inhabited, we arrived at Paita, on the 2d of July; a place of little consequence, although rendered of great historical celebrity, by the unseasonable visit paid it by Lord Anson, during his voyage in 1740, and whose name |

we found. still familiar among several of the families, whose ancestors he so ingeniously (and without ceremony too) unloaded of their cash. Soon after we had anchored, the governor, and a long tatterdemalion retinue, came off to wait upon the captain; and while they are looking at the ship, I will take a peep into the town, which is situated in latitude 5° 16' S. and in longitude 81° W. under a dry, barren, and sterile cliff, and consists of two or three rows of wretched houses built of mud and bamboo, principally without roofs, and the most magnificent among them only covered with a thin hollow matting: however, this may with ease be accounted for, as Paita is situated within that latitude on the coast of Peru, where it was never known to rain. The interior parts of the houses present a very miserable appearance; yet, I was assured, the inhabitants were very wealthy. The east end of the church alone was covered, like the houses, with a coarse matting. There are four bells attached to it, and are hung at a little distance on a frame of wood, resembling an English gibbet. The internal part of this sanctuary, as may be supposed, afforded nothing to describe. On a little eminence to the south of the town, is a small battery, calculated to, and |

mounting eight long brass pieces of ordnance, which are so badly equipped, that I think it is probable they would not stand a second discharge. This place is badly supplied with water, nor do I imagine it possible for shipping to procure any quantity adequate to their consumption, without great difficulty. The country for many leagues is barren, and uncultivated. Piura is the nearest town, in whose jurisdiction it is. In the afternoon, the governor, chief officers, and families, to the number of a score, came off to a dinner, which the captain had prepared for them, when those people, who in the morning appeared in as great a state of destitution as their houses, were clad in the most fantastic and costly attire. Some of them had even been resolute enough to shave themselves. The old priest, who besides his spiritual situation, kept a considerable shop, wishing to make bay while the sun-shone, brought off with him a bale of Guayaquil hats, one of which I bartered for an old pair of silk stockings, being more esteemed than money, but I do not imagine he found a very brisk sale. The fashion for the ladies to go without pockets, was clearly proved, not to have reached this place, for the captain's steward having missed some plate, and fancying he saw one |

of the ladies in treaty with a silver knife, he took the liberty of requesting to examine hers, where, to her great confusion, some of the articles were found; but it may be urged in extenuation of her fault, that Lord Anson, at his visit there, had played a trick or two on the family from whom she was descended. We sailed the same night, still keeping close to the shore, and passing the Islands of Lobus de Mar and Terra, arrived off the river Tumbiz, where we anchored and remained three days, cut a large quantity of wood on an Island in a small creek a little to the northward of the river: we found some foxes here, and took two. There is a bar crossing the entrance of the river Tumbiz. which renders it difficult, and at times, rather dangerous for boats to cross; notwithstanding, ships can be supplied with water which is of very good quality. It was on this place a boat belonging to the Phoebe was upset, which occasioned the death of Lieut. Jago and the Purser, but whether they were drowned or eaten by the Alligators is uncertain. Several of these frightful creatures were seen next morning basking themselves in the sun, and both these gentlemen being good swimmers, one may be led to conclude they reached the shore only to die a more wretched death. This ferocious animal, |

as it is said by naturalists, continues to grow while it lives, and those I saw were of different sizes, from six to eighteen feet. One of ten feet long was shot. They are of a dark green colour, with large and almost impenetrable scales, and, although in apposition to the opinion of many writers who have treated on the subject, I believe of considerable bravery. The town of Tumbiz, at a small distance from the mouth of the river, is of inconsiderable extent, although of some celebrity in the history of Peru, from its having been one of the last towns subjected by the Incas, and the place where Pizarro and his companions in their first expedition landed.1 In their second expedition, they again visited Tumbiz, and formed their first settlement St. Michael2 on the river Piura. After Huayna Capac the eleventh Inca, had brought this province under his subjection, which was effected without much opposition, he dedicated a temple to the sun, a most stately and magnificent temple, the remains of which I have been informed, are still visible. At the distance of a few leagues to the north, is the river and town of Guayaquil, where terminates the kingdom of 1 Garcilleso De la Vega, book 9, Chapter 2. 2 Robertsons History of America, book 6, page 125. |

Peru; Guayaquil being in the district and Vice-royalty of Quito. We next visited St. Helena, a place of little importance, and remarkable only for the high point of land, which has every appearance of being an island, until you are within a small distance of the shore. On a sandy beach to the northward of the point, is a small town, whose inhabitants are chiefly natives of the country. The houses being nothing but frames or skeletons, and having no high land behind them, appear rather extraordinary. The floor on which the people live, is about six or eight feet from the ground, and the ladder by which they ascend, is always drawn up at night, otherwise they would run great risk of being bit by serpents which infest the place, and whose bite is venomous. This reptile is very small, and nearly a yard in length. I saw but one. We took a few fish here, and likewise procured a few boat-load of water. We now steered to the Island of Plata, which to our great surprise, we found destitute of water, and, although possessed of some wood, it was not to be got at but with so much difficulty, that we left it and proceeded to the Island of Salango, between which and the Main we anchored, where we found both the above articles in great abundance. From the surf |

being continual and exceedingly violent, it is necessary to land the casks, and raft them off to the ship. The water is rather muddy, but soon settles and is very good. There are only two houses here, built similar to those of St. Helena, and are occupied by a family of the natives of the country. In this neighbourhood there are some tigers, and the serpents are of a considerable size as well as venomous. Having now completed the ships with water, we left the coast of America for the purpose of examining the group of Islands known by the name of the Gallipagos, and on the 25th July, arrived at Charles Island, and anchored in an harbour sufficiently commodious to contain a very considerable force. This Island is perfectly barren, and excepting the prickly pear tree, which grows to an immense size, and a few bushes along the beach, there is no appearance of the least vegetation. There are the craters of several old volcanoes, but I did not perceive the trace of any recent eruption. Guanas we found here in great abundance, and notwithstanding their disgusting appearance, they were eaten by many of the sailors, who esteemed them as most delicious food. We found also a great many small birds resembling, but more diminutive than the wood pigeon. They were so exceedingly tame, that |

many were, taken without the least attempt to escape, and when a stone or stick was thrown, it was seldom they flew away, but remained until struck or killed. This island is often visited by great quantities of seals. We found but few tortoises and no water. Tarrying here one day, we proceeded to Chatham Island, which excepting a small isthmus, where the volcanoes have not extended their ravages, is a perfect body of black lava. Here we were fortunate in our search for tortoises, and took more than a hundred, among them were several weighing upwards of 370 lbs. Amongst the grass on the isthmus, we took some land tortoise. One of these creatures greatly exceeded the others in size, and as the progress this species make in growing, is particularly slow, I am led to conclude it to have been of a great age. From its having been taken at this island, the sailors whimsically bestowed on it the name of Lord Chatham. It soon lost its natural shyness, became much petted among the crew, and latterly, was in regular attendance in the galley at the hour of meals, when it partook of the ships allowance, and was fed by the men either out of their hands or some of their utensils; but notwithstanding every care was taken, its life could not be preserved in the excessive cold of a high southern latitude. |

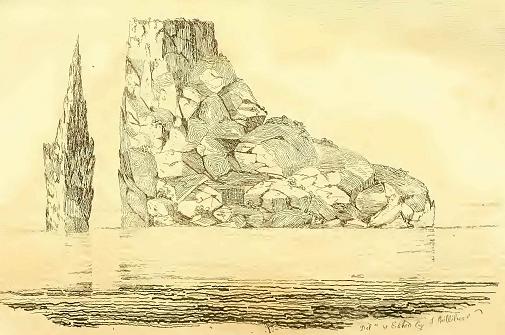

Kicker Rocks |

The Kicker rocks stand in the center of this anchorage, and has a most extraordinary appearance. In our search for water here as at Charles Island, we were unsuccessful. At James's Island we found good anchorage, a considerable quantity of wood, and at the foot of an exceedingly high and remarkable mountain, a small stream of water, near which is the remains of the hut of an unfortunate Spaniard, who was left there by his companions, and where he remained nearly two years. Land tortoises are found here in great abundance, whose meat being very fine, we found it a great relief from salt provisions. The number of guanas we saw here, can alone be conceived; they had regular burrows, and were much more plentiful than I have ever seen rabbits in a preserve in this country. They are of a light red colour, about two to three feet long, and when pursued, do not like those at Charles island, take to the water. Among some green bushes near the beach, is the tomb of Lieutenant Cowen, of the United States Frigate, Essex, who fell in a duel with Mr. Gamble of that ship. That this unfortunate young man was much esteemed by his brother officers, is evident from the great respect they paid to his memory. The thermometer in the shade, at 88° on board, and on shore, also in the shade, at 95°. |

Albermarle Island, the most extensive of this group, is nearly covered by the numerous volcanic erruptions, which appear to have recently taken. place. It possesses no fresh water, but the numerous plants and shrubs would, to a botanist, be a source of infinite gratification. Many of those plants, and which are exceedingly beautiful, grow immediately from solid lumps of black lava, not having the least appearance of possessing any thing sufficiently nutritious, or at all calculated to support a shrub in so high a state of vegetation. I removed one on board, and although a very considerable quantity of the lava was taken with it, it died immediately. It had a leaf resembling velvet, and when broken, an abundance of milky juice of a strong astringent nature issued. This plant was very odorous. There are some small birds here, also lizards and grasshoppers, the latter are of great size as well as beauty. Norborough Island, vies with the others in its dark, gloomy, and mountainous appearance. It is covered with volcanoes, and two were burning when we passed it. This Island does not possess fresh water, or vegetation. There is a very strong and continual current or indraft towards this group, which I suppose supplies the numerous volcanoes, with which they collectively abound. |

Our examination of these Islands occupied us ten days, when we again put to sea, and after a short voyage arrived at the more pleasing, as well as interesting, group of the Marquesas. |

CHAPTER IV.We had departed from those gloomy Islands, 'ere we perceived it to be the intention of Sir Thomas Staines to visit the Marquesas; but the course he ordered the ship to be steered, soon demonstrated his object, and on the 14th day, subsequent to our departure from Narborough, we arrived at Novaheevah, or Sir Henry Martyn's Island, having run in that period a distance exceeding 3,000 miles. At our approach to Port Anna Maria, it became almost a calm, when we were met by a boat, apparently European, which proved to have belonged to one of the whalers taken by the United States Frigate Essex, and now in possession of Wilson, a native of England, who having left an English merchant ship about ten years before, remained there ever since. It was necessary to anchor off the entrance for the night, and early next morning, availing ourselves of the sea breeze, we entered this delightful harbour, when we anchored in a small bay, which Captain David Porter, of the United States Navy, had occupied, and on an adjacent mountain had thrown up some works for his protection, of which, in |

the course of this chapter, I shall have to treat more largely. We were now informed by Wilson, that our appearance off the Island, had been the occasion of considerable alarm, and that the Natives, (dreading it to be the return of Captain Porter, who, doubtless, would have taken ample vengeance for the fate of those of his men, whom they had stoned to death, in retaliation for the brutal conduct he exemplified towards them, during his stay in the Port;) had deserted the Valley, and were seeking safety by flight; but on finding our ship to be of another nation, they soon returned, and at our approach, the shore was crowded, each waving a branch of the palm tree as a signal of friendship. As the first boat drew near the shore, about thirty of the natives ran into the water to receive her, which was done with so much dexterity and strength, that she was carried bodily upon the beach, without giving any of the crew sufficient time to quit her. This had a much prettier effect than I can well describe, and I was infinitely more pleased at beholding such a demonstration of friendship, than I possibly could have been at experiencing it. The Captain now waited on the King in form, who received him with great kindness and made every friendly proffer of assistance. His Majesty after having asked how many pigs, |

bread-fruit, and cocoa nuts we wanted, solicited to know the number of ladies both ships would require, because he was doubtful his valley would be deficient, and in which case, he would send to a neighbouring kingdom for a supply. His politeness was fully appreciated, and I believe there are few Royal Personages of the present day who would be more accommodating, or give to their friendship a greater latitude. The first ceremony being over, – a friendship established, – and the intercourse with the natives becoming unrestricted, each successive day was productive of something new; but 'ere I proceed to the relation, it may not be improper for the information of those of my readers who are not adepts in geography, if I take a brief view of the local situation of the Island, which is one of the most considerable, as well as fertile, among the group lying within the Latitude of 8° and 10° south, and in longitude 138° 15' to 140° 25' west, and discovered by Don Alvera Mendana de Neyra, in the year 1595, who named them jointly, the Marquesas, in compliment to Mendoca Marquis de Canete, the then viceroy of Peru, under whose auspices he had been sent out on a voyage of discovery. Subsequent to this period, they have been often visited by ships of different nations, and it has been asserted that Ingraham, an American, |

was the first who discovered Novaheevah, and from which I am inclined to suppose, Captain Porter's pompous and ridiculous claim to priority of discovery is founded: but the Islands Ingraham seen, appear to be those mentioned by the French Navigator, Le Merchand, and are situated at a small distance to the north west of the Marquesas. Novaheevah, the signification of which I could not ascertain, received from Lieut. Hergest, the name of Sir Henry Martyn's Island, and by which it is now generally known. This island, as I have already said, is not only more extensive than the others, but also of greater fertility. It is divided into several districts or vallies, each containing from 1500 to 2000 people, with an hereditary King attached to each. These Tribes or Nations are frequently at war with each other, but I believe seldom come to a general battle, and which is as seldom sanguinary; still the mode they pursue, may be productive of greater calamity than the loss of a few slain. They frequently go by night into a neighbouring district, and destroy the bark from every bread-fruit*, or Cocoa-nut tree they meet with, which * After the bread-fruit tree has been thus treated, it is five years' ere it will again bear fruit. |

being their general food, a ravage of this kind is certain to involve the unfortunate district in want for several subsequent years; insomuch that its inhabitants become dependant on the adjoining villages for subsistence. In the several kingdoms of the Pytees, Haupaws, and Typees, I saw an exceeding number of trees which had undergone this barbarous operation, and from whence many of the inhabitants had not only been obliged to remove, but to solicit the aid of their neighbours. Port Anna Maria, or the bay of Tuhuony, forms one of the most considerable districts of which the natives call themselves Pytees – beyond the mountains are the Haupaws, and those inhabiting the Valley in Comptroller's Bay, are called Typees, who are said to be the most warlike in the Island, as well as being a species of the Anthropophagi, but I am yet to learn, how they gained this unnatural reputation, for when I made an incursion into the interior of their country, I could not perceive the least trace of cannibality among them, or aught, to authorize my drawing so horrible a conclusion. The manners and customs of those tribes, resemble each other in every thing, but, perhaps, those of the valley of Tuhuouy are the most civilized, as it is a Port where ships occasionally touch for the purpose of procuring Sandle wood for the market of Canton. |

This place is surrounded by a ridge of mountains of most inaccessible height, forming the boundary of the kingdom, which is divided and subdivided into villages or districts, each having a chief, tributary to the king, who is at all times ready to lead his warriors to battle at the sound of the conch. Every kingdom has a chief priest, and to each of the divisions a subordinate one, who are much respected, and ever held in the greatest veneration. Their religion, as well as their mode of performing it, appears to differ but little from the description given in the appendix to the Missionary voyage to the Society Islands, excepting that of offering human sacrifices to their Eatooa or God. I could not find that this custom had ever been in practice here; if it had, it must have been very ancient, for it did not form any part of their numerous traditionary stories, The Eatooa appears throughout these Islands, to be the superior deity, but they have many of inferior note, and amongst them I remarked Fatu-aitapoo, and two or three others ,resembling in sound those mentioned in the Missionary voyage, (page 143) but the one here mentioned, alone corresponded exactly. Every family have also a deity of their own, taken from an illustrious relative whom they suppose, has from his virtue, or great actions, become |

an Eatooa. To him they dedicate images cut out of wood, and although the figures are uncouthly represented, they are very ingenious. These are sacred, and principally used for the tops of crutches, or stilts, as they are superstitious enough to suppose, that when they rest on these images they will be secure from injury; and if by accident they are unfortunate enough to stumble, it is seldom they live long afterwards; for if the Priest cannot satisfactorily appease the anger of the Tutelar Eatooa, they fancy they labour under his displeasure, and with an unequalled resignation and calmness starve themselves to death. In the performance of all ceremonies, they exemplify the greatest devotion, nor do they at any time approach a place sacred to the Eatooa without the most marked respect. The women uncovering their bosoms, the men removing their hats. Of the evil demon or Veheene ihee, they have but little dread, being firmly persuaded that after the soul has taken its departure from the body, it will enjoy a rank among their Eatooas in another world, according as its life has been good or bad in this. Nothing can exceed their superstition; they are constantly seeing Atoowas, or Ghosts, and even in their sleep, even, they fancy the soul leaves the body to repose among its kindred spirits. |

The morais, or burial places at this place, are greatly inferior to what I was led to expect, as from the description of several navigators I anticipated something exceedingly handsome, but they consist merely of a large heap of stones, very irregularly piled, having on the top a small house for the purpose of receiving the remains of the King, his family, or those of the principal Chiefs; the sacrifices are also made here, and from the place being Tabooed, or rendered sacred, the women, who labor under great restriction, are precluded from going to, or even touching it, under the heavy penalty of death. Their regret at the loss of a friend is demonstrated in various ways, and are borne away by the most opposite and sudden gusts of passion; and if a woman be weeping over a dead child (for they are very affectionate) you may expect (as I was informed) her sorrow to be turned into joy, and that she will be laughing with a glee equal to her former grief; but nothing of this nature came immediately under my notice. Their places of public assembly, are much superior to the morais, and are generally extensive enough within to contain 1000, or 1200 people. This spot is also tabooed, and consequently the ladies, whose interference in any political matter is never allowed, are prohibited |

The exchanging names, or becoming a brother with a chief, or native, seems to be a general custom, and indeed there can be no greater advantage to a stranger, for when an adoption of this nature takes place, the chief considers his Tayo, or brother, equally with himself, entitled to what his bouse, or district affords, and his people pay him the same respect. Patookee, a chief of great celebrity, solicited a Tayoship with me, to which I acceded, when he placed on my head his own hat as, a token of friendship. It is of a simple, structure, made from the leaf of the palm tree, but I shall ever hold it in the greatest estimation. The benefit I derived from my new connection was incalculable – he was in constant attendance, and seldom came without offering me presents. From this Tayo there is nothing withheld, even the most favorite lady would be ceded with the greatest complacency. The reader will, I doubt not, imagine where female chastity is so little esteemed, and of no recommendation to the sex, there can be but a small portion of the affection of a father, a husband, or a friend. The wife too, he may suppose, is equally callous to every feeling of |

sensibility: – but I can assure him, an impression of this kind would be very erroneous, for I am firmly persuaded, notwithstanding their readiness to deliver their wives, or daughters, into the embraces of strangers, they possess to an eminent degree the finest feelings of friendship. I have often seen the men fondling and hugging their children with as great appearance of affection, as can well be described, and that the women are impressed with the strongest attachment for their immediate Lords, the circumstance I am about to adduce will be sufficient to prove: – Lieut. Bennet, of the Royal Marines, took for his Tayo a young man of an exceedingly interesting and penetrating countenance, in stature manly, and whose wife possessed more than ordinary beauty. From the attention shewn him, he conceived a desire to visit England, and was, I believe, promised permission should be granted him. His intention was soon communicated to his wife, who an evening or two after, when we were walking on the beach, came up to us in the most frantic and wild manner, talking with unequalled rapidity, but not a word could we distinguish but "Vahana Picatanee" or husband to England. She cried and laughed alternately, tore her hair – beat her breast – lay down on the ground – danced,–sang, and |

at length in a paroxysm of despair, cut herself in several places with a shark's tooth, which until then she had concealed, nor could we disarm her before she had done herself considerable injury. She was still frantic, and we still ignorant of the cause, and should have remained so, had not Otaheitean Jack* arrived, who informed us, when we assured her, her fears were vain, and that her husband should not be permitted to go from the Island without her leave. This had the desired effect, and she soon became as placid and cheerful as ever; nor did she appear to notice the wounds she had inflicted. There were several spectators to this affecting scene, which clearly proved that the natives of this remote region, although in a perfect state of nature, are neither destitute of feelings nor affection. Old age is no where more respected or revered than here. I am decidedly of opinion that the custom of having plurality of wives is confined to the chiefs alone, and that the people in general are constant to one, and in this I am supported by the opinion of Crook, the Missionary, who says, speaking of the Island of St. Christina, * A Native of Otaheite, who had been taught a little English by the Missionaries. |

(M.V. page 144.) "Observing a pregnant woman I asked her how many children she had? She replied three. I wished to know if they were all by the same man? she said yes. I asked farther if he had any other wife? she said no. Whence I am led to believe that though Tenae* has more wives than one, this is not usual, and may be the privilege of the chief." The continuation of this paragraph, tends greatly to strengthen what I have already said, relative to their affection, for says he, "They seem to be very fond of their children, and when I went up to the valley, I saw the men often dandling them upon their knees, exactly as I have observed an old grandfather with us in a country village." The Nooaheevahans, like most of those of the other Islands, have no regular meals, nor are the women employed in any part of the cookery, except for themselves, and are prohibited from eating at all of the hog, notwithstanding they are very fond of it, for those who came on board ate of it most voraciously. They do not eat much at a time, but their meals are frequent, and their dishes consist chiefly of the bread-fruit roasted, fish, which they eat raw, Ahee-nuts, a root resembling the yam beat in- * Chief or King in the Island of Christina, by whom Crook the Missionary was patronized. |

to a paste, and roast pork. Poultry they have also, but in no great abundance, nor did they appear to like its meat. These articles are generally served up in calabash, or cocoa-nut shells – their knives are made from the outside of bamboo, and their forks of the same materials, but resembling a wooden skewer. These instruments are seldom used, but for the first separation. It is rarely they employ themselves at work, and excepting a few old men, who were making nets, or canoes, I never saw any, The clothing, or dress of these people is very simple, the men having nothing but the ame or girdle of cloth round their waist, which is passed between their legs and neatly secured in front. They have also a hat made from the palm tree, the simplicity of which gives an interesting finish to their manly statures. They are excessively fond of ear ornaments, the men making theirs from sea shells, or a light wood, which by the application of an earth, becomes beautifully white. The women prefer flowers, which at all seasons are to be found. Whales teeth, are held in so much estimation, that a good one is considered equal to the greatest property; they are generally in the possession of the Chiefs, who wear them suspended round their neck. Their other species |

of dress consists of a kind of Coronet, ingeniously made from a light wood, on which is fastened, by means of the rosin from the bread-fruit tree, small red berries; a great quantity of feathers give the finish. The ruff worn round the neck, is made of the same materials. Added to these are large bunches of human hair, tied round the ancles, wrist, or neck, and always worn in battle, though seldom otherwise. Tattooing is evidently considered among them a species of dress, a man without it being held in the greatest contempt. The women are not exposed as much as the men, and their tattooing is very inconsiderable. Their dress, consists of a piece of cloth round their waists, answering to a short petticoat, and a mantle, which being tied on the left shoulder, and crossing the bosom, rests on the right hip, and hangs negligently as low as the knee, or calf of the leg, as it may accord with the taste of the lady. Their hair is generally black, but worn in different ways, some long, and, turned up – others short. They are all fond of adorning their persons with flowers, and many of the wreaths are formed with such elegant simplicity, that does not contribute a little to their personal appearance, which is at all times particularly interesting; the beauty of their features being only equalled by the symmetry of their figures. They are of a |

bright copper colour, and in the cheeks of those who were requested to refrain from anointing themselves with oil, and the roots of trees, the crimson die was very conspicuous. In their early visits to the ship, they swam off; and as their clothes are not calculated to stand the water, they left them on the beach; but they never neglected taking with them a few leaves to tie round their waists. In this state of nature would they daily exhibit themselves, and too without suspecting, or being in the least degree conscious they were offering the most trivial offence to modesty. "Our first visitors," say the Missionary Voyage, "came off early from the shore; they were seven beautiful young women, swimming quite naked, except a few leaves round their middle; they kept playing round the ship for three hours, calling Waheine, until several of the men came on board; one of whom being the Chief of the Island, requested that his sister might be taken on board, which was complied with: she was of a fair complexion, inclining to a healthy yellow, with a tint of red on her cheek, was rather stout, but possessing such symmetry of features, as did all her companions, that as models of Statuary and Painture their equal can seldom be found. Our Otaheitean girl who was tolerably fair, and had a comely person, was, notwithstanding, greatly |

eclipsed by these women, and I believe felt her inferiority in no small degree however, she was superior in the amiableness of her manners, and possessed more of the softness and tender feeling of the sex: she was ashamed to see a woman upon the deck quite naked, and supplied her with a complete dress of new Otaheitean cloth, which set her off to great advantage, and encouraged those in the water, whose numbers were greatly increased, to importune for admission; and out of pity to them, as we saw they would not return, we took them on board, but they were in a measure disappointed, for they could not succeed so well as the first in getting clothed nor did the mischievous goats even suffer them to keep their green leaves, but as they turned to avoid them they were attacked on each side alternately, and completely stripped naked." I must confess, when I read this paragraph, notwithstanding the respectability of the authority, I was rather inclined to be incredulous, but 'ere we had been at anchor many hours, a similar circumstance took place, and afterwards several others, and to which I was an eye witness. Tattooing, or Patekee, is considered a great mark of distinction, the pain being of infinite acuteness, it shews what they are capable of |

undergoing. There are many on whom it has been performed so often, that not a spot of their natural colour is seen to remain. Some are most fantastically done, although with great taste, and if it be possible, straight lines are always avoided. Those who are marked only sufficient to shew the class they belong to, are of the inferior order, or toutous, and have, perhaps, a fish, a bird, or something of little consequence, represented on one side of the face. The women, as I have before observed, are so little marked in this way that it seldom exceeds a hand, or a few fingers. The lips of many are streaked, and this is principally seen with those who are married, or have children, but it is not as many suppose a general rule among the married. The men are tall, well formed, muscular, and manly; possessing a great portion of vivacity and penetration; insomuch that for a people of whose language I was ignorant, I had less pains in making them understand me than any I ever met with. They took notice of every thing they saw, and I believe no one came on board who did not measure the length of the ship, and count the number of guns, masts, decks, &c. Their amusements are principally in dancing, swimming, and wrestling; throwing their javelins, and slinging stones, in the whole of |

which they are great proficients. Their arms consist of clubs, of which there are two kinds, the carved, and the plain, both made from a wood, though not hard when first cut, becomes so by being buried in the mud which serves as a strong die. Spears of 10 feet long, made from the same wood, or from the cocoa-nut tree, and slings made from grass. Bows and arrows have not yet been introduced among them. The stone from the sling is thrown a great distance, and with considerable accuracy. The person o£ the king being tabooed, whatever place or ground he touches becomes sacred, and to obviate the inconveniency to which his people would otherwise be subjected, he is at all times carried on a man's back, his conch, or horn, slung about his neck, and a small diadem, made of leaves, on his head. Several of the principal chiefs are in constant attendance, as well as a retinue of domestics. In his palace he has a canopy of state, under which he sits, or lies – there is great simplicity in its appearance. The palace is an open hut, situated near the sea-side, and has nothing, except its size, to distinguish it from any of the others. One of the rooms was curiously decorated with the skeleton heads of pigs, exceedingly clean, and well preserved. These animals, to |

a great number, had been sacrificed at the death of the king's mother, and whose heads were fixed round this apartment, by way of keeping her alive in his memory; but however dear she might have been to him, he did not hesitate to barter a couple of the best for an old razor. Their candles are made by sticking a great number of the kernels of nuts on a long slip of bamboo, and from their oily nature, they are easily lit, burn very regular, and produce an exceedingly good light. There is a very small portion of smoke, and when the light is extinguished, the smell though rather powerful, is by no means disagreeable. The quadrupeds consist only in pigs, and rats, the latter are exceedingly large, and in very great numbers, the pigs run wild, and are of a fine sort. I brought one of them to England with me, which being with young at the time of landing, I have now in my possession the species entire. The natives on seeing our cow, were much surprised, and called it a horned pig, not having seen any of the species before, or having the least idea what else it could be. The natives of this place do not bleed their pigs, but strangle them with a rope, and after having taken out the entrails, and binding |

the body up with large leaves, it is laid on a heap of hot stones, which burns off the hair, and dresses the body; and had the one so prepared for us by the Tytees in Comptrollers bay, been a little more dressed, I am persuaded no dish could have exceeded it: it was full of the richest gravy and was in every way calculated for the exquisite palate of an alderman, who I am inclined to believe, would have taken it in preference, even to the callipee, or callepash, of the most delicious tortoise. The cava, or spirit, drank here, possesses very inebriating qualities, and brings on almost immediate dizziness. It is produced from the leaves, and roots of a plant, which being chewed by women of the lower order, and spit into calabashes, or receivers, and mixed with the milk, from the cocoa-nut, is left to ferment; after which it is strained off, when it soon becomes fit for use. The kings, and a few chiefs, can alone afford to indulge themselves in this delicious nectar, and to those it produces a kind of dry scrofula in the skin, with soreness in the eyes, which was very conspicuous in the old king, for, notwithstanding he had undergone the ordeal of Tattooing to an immense degree, his skin was covered with such a dry |

white scale, that it gave him, instead of a black, the appearance of being a light grey colour. These people are seldom visited by sickness, which may in some measure be attributed to the simplicity of their diet, and their great attention to cleanliness. It is considered necessary with them to bathe at least three times a day, which greatly diminishes that sour offensive exhalation, proceeding from those people of a similar climate, who are less attentive to their persons. In case of accidents, there are people who profess the art of surgery, and in setting fractures they are expert, and successful. I saw but one operation of this nature, which was on a broken thigh – the swelling being reduced, the part fractured was bound carefully round with large leaves, when several splints, or smooth pieces of bamboo, were applied, which being bound with great caution, and the limb confined in one position, the operation was finished. One of the faculty was solicitous to be supplied with lancets, but I could not ascertain from Wilson, if phlebotomy had ever been practised, or if the old man understood the use of these instruments. However, he was furnished with enough to open all the veins in the Island. Sir Thomas Staines taking great interest in |

the voyage, and wishing to know beyond a vague conjecture, their mode of fighting, solicited the old king to cause a sham fight to be performed upon the plain, which he acceded to, and the old warrior, took great pleasure in going through all the various evolutions. For the club, a tolerably sized stick was substituted – for the spear, a piece of bamboo, and the slingers, instead of stone, threw the small bread-fruit. Thus armed, about 300 of the most experienced went forth to the plain. The king, for the first time, was carried on a superb litter, which we had made for him on board. He gave direction to the chiefs, for the formation of both armies, which were drawn up in the following manner. About thirty principal warriors, with clubs, formed the first line – the second was composed of spearmen, and the slingers on the flanks. The battle commenced by a single combat between two chiefs, who displayed great powers, both in agility, and skill, and were struggling manfully when the signal was given to advance. A terrific and hideous shout followed. The slingers now began, but were obliged to retire on coming within the reach of the spears. The advance was rapid, and as the parties closed, so did the confusion increase. Club came in contact with club, and spear with spear, – the |

slingers stood aloof. The conch was at length sounded, when each party separated, the slingers, on either side, filing into the rear of their respective flanks to secure their retreat. They did not cease throwing stones until they were rendered of no effect. Both parties again drew up in their original order, and rested on their arms. The distance, as well as accuracy with which they throw a stone is almost incredible – the spearmen are also very expert. The countenances of many by being hit by shot from the slings, became quite ferocious – many were knocked down, but none received injury, and thus ended the representation of a battle, which must have been productive of great pleasure to every beholder. The principal trees are bread-fruit and cocoa-nut, as from their produce the natives derive their subsistence, but there are various others, which together with a variety of plants and flowers, would afford the botanist an extensive field for speculation, and I regret to say I had no knowledge in so pleasing, as well as useful a science, or I certainly should have turned it to advantage. There are several fine streams of water, and ships may at all seasons be supplied without difficulty. There are also several mineral springs, but the qualities they possess I was wholly inadequate to ascertain. |

The language spoken here, is by no means harsh, and principally formed from vowels, but I could not learn from Wilson, who is most egregiously ignorant, if like most others, it had any particular form, or government, or what it was; nor could I make myself sufficiently understood among the natives to ascertain it from them, but what I could collect, I shall here introduce, and I trust it will be not unacceptable. Their manner of counting is rather irregular, as they only count to twenty, and then the number of twenties, as will be seen by the following tables, to which I shall add, all the words, and expressions, we could gather during our stay, which we found of great use. A table of numerals used at the Island of Novaheevah Marquesas.

It will be necessary to observe, that the Eleventh number is formed by the addition of |

"Om," to the first and the Twelfth by the same addition to the second, and so on to Twenty when they stop: – as

To count a greater number than Twenty, they would say for the first "Atachkee Omnahoo" and commence afresh with the first number, and "Ahowa Omunahoo" would be the second twenty, or forty, and so on: but they are by no means expert in any kind of calculation. The following phrases we found of considerable use.

|

|

A list of words we collected during our stay at Port Anna Maria.

|

The marvellous stories related by the American Officers, who had been taken in the Essex, and who were at Valparaiso, when we arrived there, relative to the ferociousness of the people, inhabiting the interior of this Island, had greatly excited my curiosity, and 'ere we reached Port Anna Maria, I had made up my |

mind to ascertain beyond a doubt, whether the terrific description given of them was correct; and to accomplish this point, a party of several officers was made, and every arrangement necessary for crossing the mountains entered into: however, when the period came, from causes which I cannot explain, we were reduced from the number of a dozen to only three; namely, Lieutenant J. Morgan, commanding the Marines of the Tagus, Mr. Blackmore, Midshipman of the Briton, and myself. To these gentlemen I shall ever feel myself obliged; for had they forsaken me also, I should not have relinquished the journey, but have gone alone, and their company and observations were throughout the day, both agreeable, and interesting. It was soon after day-light when we set out, accompanied by my Tayo Patookee, as a guide, and Otaheitean Jack as interpreter. In the two preceding days to our journey, a considerable quantity of rain had fallen, and the road which bore the appearance of being always bad, was now become almost impassible, insomuch, that each step we ascended, the difficulty increased, and in many places, and for several yards together, the mountain was so steep, that had it not been for the roots of trees, forming themselves into steps, any attempt to |

cross by this route would have been vain. – About nine o'clock we reached the summit, where we tarried awhile, not only to take some refreshment, but to gaze on the various beauties of nature as they presented themselves. It was impossible to turn the eye, where it was not met by the most romantic scenery. We had now full three miles farther to walk, before we could reach the country of the reputed Cannibals, and as the road did not bear a very favourable appearance, we hastened our departure from the spot, and proceeded on our journey – we had not gone far before we were met by some natives, inhabiting the small, though comparatively level district, through which we were passing, who brought us cocoa nuts, and demonstrated their joy and friendship, by a number of strange actions, which pleased the more because it augured a favorable reception from the Typees. This country is of a deep rich soil, and capable of the greatest improvement. The cocoa-nut, and bread-fruit trees, are every where conspicuous. – There are also some sandle trees found here. It was nearly noon before we completed our journey, (about ten miles from the port) when we were received, and treated with great kindness by those terrific people, whom Captain Porter speaks of as having conquered and ren- |

dered tributary to the American flag. The whole seemed pleased, and their satisfaction at seeing us was expressed in various ways, some danced, others sang, knelt down, embraced us, with many other laughable actions, which would be impossible for me to describe. They anticipated our wishes in every thing. The cocoa-nut for our refreshment was presented us, as well as clubs, spears, slings, &c. &c. as pledges of their regard, and which they caused one of their people to carry even to the ship. They examined every thing we had with us, and were greatly astonished at the whiteness of our skin; several of them opened the bosom of my shirt, the sleeves of my coat, the bottoms of my trowsers; and one was even so incredulous as to wash my hand to ascertain if it was not painted. At this time, we were in the place of assembly, surrounded by more than five hundred of them, and I must confess I did not like so strict an examination, which was, however, put a stop to by my friend Morgan, who with Mr. Blackmore, was undergoing a similar process. At his discharging a pistol in the air, the whole assembly fell prostrate, and in which attitude they remained a considerable time, or until they thought the shot had reached its destination. When they were about to rise, a second was fired, which was |

productive of the same effect. This scene was so truly ludicrous, that to have withheld from laughing would have been morally impossible. When they had recovered, at their request, the pistols were several times discharged, but during the rest of the day, every one observed the most accommodating distance. I have not the most trivial thought of their having been actuated by aught but curiosity, for had they entertained a hostile thought, our being armed with pistols would not have intimidated them; we were so few in number, that one volley of stones, from their slingers, would have given them quiet possession of our bodies. On this occasion I received great assistance from my Tayo Patookee, as well as on every other, during the whole period of our stay in the Island. The Morais of this place, like those of Tuhuony, are by no means handsome, but the square of public assembly is much superior, and sufficiently spacious to contain 1200 people: it is also well built. The manners and customs of this tribe, appear in every respect the same as those at the Port, or Tuhuony. The land is very luxuriant, but nothing is propagated; save the few trees from whose fruits they subsist, which grow almost spontaneous. There is not any sugar cane, though |