Reports of Admiral Robert FitzRoy's Suicide

This page contains newspaper and magazine notices of the Admiral's death, with paragraph breaks inserted here for readability. Despite some repetition, each report offers some information not found in others. Original spelling and punctuation is retained; a phrase [within brackets] indicates an editorial insertion in this online page. Newspaper title is followed by page number (in parentheses), location and publisher's name.

(p. 7) — London: John Walter

SUICIDE OF VICE-ADMIRAL FITZROY.

Yesterday morning a painful feeling of regret agitated the whole of the officials of the Board of Trade, on assembling at Whitehall, when the melancholy news of the suicide of Vice-Admiral Fitzroy, the chief of the meterological division of that department of the Government, became known. He cut his throat at his residence, Lyndhurst-house, Norwood, on Sunday morning [April 30, 1865].

The unfortunate Admiral was the youngest son of the late General Lord Charles Fitzroy by his second marriage with Lady Frances Anne Stuart, eldest daughter of Robert, first Marquis of Londonderry. He was born on the 5th of July, 1805; entered the navy in October, 1819, and obtained his commission as lieutenant in September, 1824. After serving on the Mediterranean and South American stations, he became, in August, 1828, flag-lieutenant to Rear-Admiral Robert W. Otway, at Rio Janeiro, and obtained his commission as commander in November of the same year. He was employed as commander and captain of the Beagle from 1828 to 1836 in important hydrographical operations in South America and elsewhere, carrying on surveys and a chain of meridional distances round the globe. In 1843 he was appointed Governor of New Zealand, which appointment he held three years, being recalled owing to the disturbed state of the colony. Previously to going to New Zealand he was elected, in 1841, M. P. for the city of Durham.

Admiral Fitzroy's scientific researches in meteorology have procured him the highest reputation in that branch of science. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society, a Fellow of the Asiatic Society, and many other learned bodies. The late Admiral Fitzroy was twice married,—first in December, 1836, to Mary Henrietta, second daughter of the late Major-General [Edward James] O'Brien, which lady died in the spring of 1852; and secondly in April, 1854, to Maria Isabella, daughter of the late Mr. J[ohn]. H[enry]. Smyth, of Heath-hall, Yorkshire, who survives him. He leaves a son and two daughters by his first marriage.§ The Admiral's only sister [Frances] is married to [George Rice Trevor, 4th] Lord Dynevor.

Robert 1839-1896

Fanny 1842-1922

Katherine 1845-1927

Laura Maria Elizabeth 1858-1943

For reasons unknown, FitzRoy's fourth daughter, Laura, by his second marriage, is not mentioned here or elsewhere. And yet she was hardly unknown: Lady Nora Barlow interviewed her in 1934, one year after editing her grandfather Charles Darwin's Diary. Miss FitzRoy said of Darwin:

“He had been raised up for a special purpose, but he overstepped the mark. Yes, he overstepped the mark for which he was intended.” (in Lady Barlow's “Foreword” to H. E. L. Mellersh's FitzRoy of the Beagle.)

Poor Mrs. FitzRoy would go, & the two daughters § were with her.

§ Presumably, Fanny and Katherine. The 7-year old Laura may not have attended due to her age.

Thursday, May 4, 1865 (p. 14)

THE SUICIDE OF ADMIRAL FITZROY.

Yesterday, Mr. William Carter, one of the coroners for the county of Surrey, resumed the inquest which had been formally opened on Monday evening on the body of Admiral Fitzroy, who died by his own hand on the morning of Sunday last, at Lyndhurst-house, Upper Norwood, under circumstances which were partly narrated in The Times of Tuesday. The inquest was held at the White Hart Tavern,§ in the neighbourhood of the deceased gentleman's residence, before a highly respectable jury, summoned from among the principal inhabitants, and of whom the Hon. Plantagenet Pierrepont Cary §§ was elected foreman.

§ White Hart Tavern, 367 Norwood Road, West Norwood, London SE27 9BQ.

§§ British Navy Admiral, and later (1884) 11th Viscount Falkland.

The sad event has cast profound gloom over the whole neighbourhood, where the deceased admiral was held in high esteem alike by rich and poor, as well for his genial and amiable qualities as a man as for his great repute in the branch of science to which he had especially devoted himself, and which had made his name a household word to the whole seafaring population of the country. Only a few weeks ago he attended an evening meeting of the Royal Geographical Society, of which he was a valued member, at Burlington-house, and took part in the discussion which arose on the projected expedition to the North Pole. He appeared then in high health, and the whole audience listened to what he said on the subject with evident interest and pleasure. He was a man of fine presence, with a handsome countenance, and although just turned sixty years of age, he looked ten years younger.§

§ FitzRoy's 60th birthday would have been two-months hence; 5 July.

At the inquest yesterday, Mr. Farrer, § solicitor, was present to watch the proceedings on the part of the family of the deceased gentleman.

§ Frederick Willis Farrer (1829-1909).

The principal witness called was Mr. Frederick Hetley,§ M.D., and Fellow of the College of Surgeons, residing at Norwood. He said–On Sunday morning last, at half-past nine, I was called to Lyndhurst-house, the residence of the deceased gentleman. Entering a dressing-room, I saw him lying on his back, with his head close to the sponge-bath on the floor in a corner of the room.  I noticed that he had received an injury in the throat. He was alive. He appeared to recognise me, but did not speak. I attended to him, and did all that was necessary. The nature of the injury was an incised wound, extending from the left side of the neck to the right ear. From the nature of the wound, the instrument appeared to have been used more than once, although there was only one principal wound. I saw a razor in the bath, in which was also a quantity of blood – three pints at least. The razor produced might have caused such a wound. The wound was in such a position that he could have inflicted it himself. The windpipe was so much severed that he could not speak.§§ I saw nothing indicating that any person had caused the injury but himself. I anticipated his death. He survived only an hour and three-quarters.

I noticed that he had received an injury in the throat. He was alive. He appeared to recognise me, but did not speak. I attended to him, and did all that was necessary. The nature of the injury was an incised wound, extending from the left side of the neck to the right ear. From the nature of the wound, the instrument appeared to have been used more than once, although there was only one principal wound. I saw a razor in the bath, in which was also a quantity of blood – three pints at least. The razor produced might have caused such a wound. The wound was in such a position that he could have inflicted it himself. The windpipe was so much severed that he could not speak.§§ I saw nothing indicating that any person had caused the injury but himself. I anticipated his death. He survived only an hour and three-quarters.

§ Dr. Frederick Heatley.

§§ Apparently his vocal cords were severed, but not his windpipe. If the latter had indeed been severed, he would not have lingered for several hours.

I had a knowledge of the deceased professionally from the 18th of April. On that day he consulted me with respect to his health. I was with him on that occasion about an hour and a half, and my deduction was that he was suffering from failing health, in consequence of over-mental fatigue, which had brought on great depression of mind, and consequent wasting of the body. I was acquainted with his position and vocation. These were likely to induce great mental and bodily depression. I also formed the opinion that he had a weak condition of the right side of the heart, and of that I informed him. On that occasion he asked me how far he might continue his work with safety to his health, and a view to his recovery, he observing that he had consulted me principally on that point. I gave him to understand that he should suspend his work temporarily. He begged me to allow him to answer several letters that he had received. I told him that he had not power at that time, meaning not mental power. There was apparently no acute disturbance of the mind at that time, but he was in a state that insanity might arise. I prescribed for him in regard to his bodily health, and did all that was neccesary in regard to his mind. On the 21st I saw him again. On that day I was sent for to go and see him immediately. He was then seriously ill, and I found him in a drowsy condition, resulting from a dose of opium he had taken to produce rest, in consequence of a sleepless night he had had, following a most exciting day. I saw him frequently in the course of that day (the 21st), and on the following day he was relieved of the effect of the opiate. I saw him daily from the 22nd of April up to Thursday last. I am not aware that he did anything at all in that interval. In fact, I should have considered him at that time incapable of following his profession. I had a long walk [sic, talk] with him on Thursday, but his mind was not in a fit state to bear excitement. He had called at my house on Thursday, and on his return from a walk I met him. We then spoke about his condition, and he asked me to give him a point-blank opinion about it. I felt it advisable to give him an answer. The opinion he asked was whether he should give up his work or not. That was always the question he put to me. My reply was, that he was quite incapable of carrying it on, and that if he attempted to do so serious consequences would result.

The Coroner. – What did you mean by serious consequences?

Witness. – That is exactly the question the admiral put to me, and I replied that the result would be a condition of the brain that might lead to paralysis. He said he was grateful indeed to me for telling him so, for it might save his life. When I last saw him on Thursday, he was better than he had been a few days before. He was, however, in his usual depressed condition, which was always the character of his malady. From the conversations I had with him, the idea of his committing suicide did not enter into my mind. There was no distinct reason for my apprehending it.

The Coroner. – You did not think it necessary to place him under any restraint, or to give any special orders?

Witness. – No.

The Coroner. – Looking at the act itself, and the character and position of the wound, is there any doubt on your mind that he has taken his own life?

Witness. – None at all. My opinion is that he was led to the commission of the act by a power over which he had certainly at the time no control, and that he was not then of sound mind. (To the jury.) I did not see him on Friday or on Saturday. He was in town during the whole of Saturday. If sufficient excitement follow on fatigue of an over-worked brain paralysis may occur at once.

The Coroner. – Would it induce sudden delirium?

Witness. – Not unless there was also a fatigued condition of body. Delirium would occur under those circumstances: but ordinarily fever ia not an adjunct of a state of mind and body like that of the deceased.

The Coroner, – But are you quite sure the act was done when the mind was not in a condition to render him responsible?

Witness. – Decidedly so.

Elizabeth Whyman, a domestic servant of the deceased gentleman and his family, was recalled. She said she saw her master alive at ten o'clock on Saturday evening. He was then in the dining room, and all the family were with him, consisting of his wife and two § daughters. Witness took a light into the room before putting out the gas. The admiral had been from home that day. He left at half-past three in the afternoon, and returned at seven. Between his return and ten she saw him just before he dressed for dinner, again at dinner, and afterwards at tea. She heard him say he had seen Captain Maury.§§ His conduct seemed strange, and witness remarked upon it to a fellow-servant. He answered in opposition to what was said to him. He had seemed strange for some time past. She had heard him say he was tired; she understood from the fatigue of the day.

§ FitzRoy had three living daughters and one son, all listed above.

§§ U. S. Navy Captain Matthew Fontaine Maury. An oceanographer, Maury resigned his commission to join the confederacy. According to Gribbins' FitzRoy biography (p. 278), Maury wrote two articles which “… attacked the basis of FitzRoy's forecasting system. This wounded FitzRoy deeply.” Despite that, the two remained close friends and met several times during FitzRoy's final days, as mentioned below.

The Rev. Francis William Tremlett, volunteered to give evidence, and he was heard. He said, – I am a clergyman of the Church of England, and reside at Belsize park, Hampstead. I knew the deceased very well. I first heard of his death on Monday. I had been with him on Saturday. He was at my house on that day, and also on the Wednesday or Thursday previously. He remained an hour and a half. He often came to see me. He came also to take leave of Captain Maury, who was about to proceed to the West Indies, and who had been a personal friend of the deceased for many years. Both Captain Maury and I had a conversation with him about the state of his health, Maury said, “Fitzroy, you want dynamic force,” alluding to his nervous state, and meaning by that expression nervous power. The Admiral turned to me and said he wanted to have my opinion. I replied that I quite agreed with Maury. The Admiral asked on what ground I had formed such an opinion. I replied, “You know you cannot make up your mind upon any subject.” He said, “It's quite true; I cannot.” I said, “Your nervous system is unstrung; I see it by the twitching of your hands, and I judge from what you yourself have told me.” He said he was affected with noises in the ears, and was generally unable to sleep at nights. I replied that those were alarming symptoms in his condition. I urged him to resign at once his post as meteorological officer of the Board of Trade. I had had many conversations with him before upon that subject. I had also many opportunities of judging of the nature of his avocations, and I know they were most laborious. He left my house before Captain Maury left, and, after he had gone, I remarked to Maury upon the admiral being in a bad way. I added, alluding to Maury going away from the country, “My opinion is that you will never see him in his senses again.” I had often thought be would become deranged.

The Coroner. – Were you surprised to hear of his death?

Witness. – I was surprised to hear of it occurring so suddenly, but not at all at the act itself.

The Coroner. – I seriously put this question. From your knowledge of the deceased, and from what you had noticed in his conduct, do you think he was of sound mind when he committed this act?

Witness – I think not. He was always very much depressed.

The Coroner put it to the jury to say whether, after all that they had heard, it was necessary to carry the examination further into the deceased's responsibility.

The jury, through their foreman, replied emphatically that it was not.

The Coroner said that being so, he left it to them to say – first, whether the deceased killed himself; and if so, secondly, whether he was at the time responsible for the consequences which the law imposed on self-destruction – in other words, whether he was in such a state of mind as to render him responsible.

Inspector Bond, in reply to the Court, said he had searched the room in which the deceased was found, but without discovering any paper to throw any light upon the subject.

Dr. Hetley said it was right, perhaps, to state that on Friday, when the deceased had recovered from the effects of the opiate, he expressed his horror at the risk of death he had run in taking.

The Foreman. – My opinion is that deceased destroyed himself by his own hand, and that he was in an unsound state of mind at the time he did so.

The rest of the jury said they were all of the same opinion, and a verdict to that effect having been recorded to the coroner, the Inquiry terminated.

The late Admiral Fitzroy leaves a son and two daughters of the first marriage, and one little girl by his second wife, also his cousin.

St. Pancras News and Marylebone Journal

Saturday, May 6, 1865, p. 6 — London: Publishing Office, Euston Road, N. W.

Admiral Robert Fitzroy, the great prognosticator of the weather, has destroyed his life by cutting his throat with a razor. The sad event took place at Lyndhurst House, Norwood, Surrey. It appears that the unfortunate gentleman had been for several days in a very low state, but nothing particular was apprehended by his friends, who considered the marked change in his manner was owing only to over-study.

On the morning of Sunday, April 30, about half-past nine o'clock, he repaired to his dressing-room for the purpose, as was supposed, of getting ready for church. He, however, was absent longer than was anticipated, and upon some of the inmates going to ascertain the cause, they found the door of his dressing-room locked from the inside, which, as might be expected, created some alarm, more especially as a low gurgling noise was heard as if the gallant Admiral had been seized with a fit. A forcible entry was made, when the unfortunate gentleman was found with his throat cut in a frightful manner, and a razor smeared with blood, with which he had inflicted the injury, close by him. Medical assistance was at once sent for, and everything that humanity or surgical skill could devise was done to save the Admiral's life; but he survived only two hours, when death terminated his sufferings, and thus the country has lost one of the greatest men of science it ever produced.

There is little if any doubt that the act resulted from his brain having been overwrought with study, and by some concurrent circumstances which greatly excited him. Some time since, his scientific labours affected his health in such a grave degree that his medical attendant informed him of the positive necessity that he should cease for awhile from such work, and take perfect rest. To conform with this injunction he moved, about a month since, down to Norwood, where he took up his residence at the Lyndhurst. He could not, however, be brought to abandon his duties at the Board of Trade, to which he persisted in giving frequent attendance.

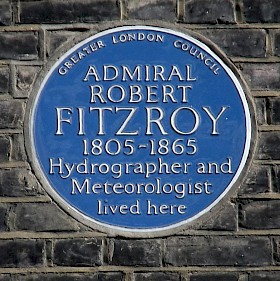

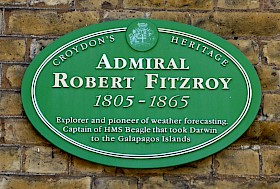

FitzRoy's residence at 38 Onslow Square, Kensington, and later at Lyndhurst House, 140 Church Road, Upper Norwood. Magnifying-glass icons show plaques (courtesy Plaques of London) at both locations.

Possessing many friends in the Confederate States of America, he was seriously agitated at the recent intelligence which has from time to time reached this country of disasters in the cause of the South, and the news that President Lincoln had been assassinated affected him gravely. On Saturday he appeared more than ordinarily depressed, but not to a degree that would inspire fear of the awful occurrence which was brought about the next morning. Rear-Admiral § Robert Fitzroy was the second and youngest surviving son of the late General Lord Charles Fitzroy (who died in 1828), by his second wife, Lady Frances Anne, eldest daughter of Robert first Marquis of Londonderry, and cousin of the late Duke of Grafton. He was born in June, 1805.

§ Promoted to Vice Admiral in 1863.

He entered the Royal Navy in 1819, and having served for some years on the Mediterranean and South American Stations, became flag-lieutenant at Rio de Janeiro to Admiral R. W. Otway. He was made commander, Nov. 13, 1828, and post captain in 1834, when he was appointed to the command of Her Majesty's ship Beagle,§ engaged in surveying the coast of South America, an account of which he subsequently published under the title of “The Voyage of Her Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle.”§§

§ While still a lieutenant, FitzRoy was made commander of HMS Beagle on its first voyage in 1828, and promoted to Post Captain in December, 1834 during the second voyage. Since a ship's captain may not necessarily hold the rank of Captain, the term “Post Captain” signified that the officer did indeed hold that rank.

§§ Actually, Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships … [emphasis added]. George IV and William IV reigned 1820-1830 and 1830-1837, respectively, during which time the first and second Beagle voyages took place. Victoria was monarch in 1837-1901, and thus Queen when the Narrative was published, but not during the time of the voyages.

He was an unsuccessful candidate for the representation of Ipswich in 1831, and sat, in the Conservative interest, as M. P. for the city of Durham from 1841 to 1843, when he accepted the post of Governor and Commander-in-Chief of New Zealand. Returning to England after having held this post for three years, he entered the civil service, and in 1855 was appointed to preside over the Meteorological Department (then just initiated) of the Board of Trade. In this capacity he practically carried out the working of that system which he did so much to inaugurate; and it is not too much to say that to him we owe the rapid, and generally all but infallible tidings of approaching storms, which, trarnsmitted by telegraph to the various ports and harbours of Great Britain, have in all probability been the means of saving so much valuable property, and many more valuable lives. An account of the progress of meteorological science in this country, and the results of the department over which the deceased Admiral so ably presided, and in which he took so deep an interest, will be found in the annual reports which were published under his superintendence, and the contents of which have often appeared epitomized in these columns.

The late Admiral married in 1836 Mary Henrietta, second daughter of the late Major General Edward James O'Brien, by whom he left issue.§

§ Details of FitzRoy's two marriages, and daughters from both, are given in the The Times obituary of May 2.

Mr. William Carter, coroner, opened an inquiry into the circumstances attending the death of the Admiral, who was aged 59 years.

Elizabeth Whyman said that she was a domestic servant at the Lyndhurst, Church-road, Norwood the residence of the late Admiral Fitzroy. On Sunday morning the little daughter of the deceased admiral went upstairs, at a quarter past nine o'clock, to ascertain if he was in his room. In a short time she came down the stairs and said, “Papa is asleep; his door is locked.” Witness then went upstairs to call him, but upon knocking at his dressing room door she received no answer.

§ It is unclear why his daughter (Laura Maria Elizabeth, age 7) would say he was asleep when he was in his dressing room, not in his bed.

Mrs. Fitzroy was then sent for, and in that lady's presence the door was forced open. The door had been bolted from the inside. Upon entering the room witness saw the admiral lying on his back in a large pool of blood. There was a deep gash in his throat. Witness perceived a quantity of blood in a flat bath § that was in a corner of the room. Mr. F. Hetley, a doctor residing in the Church-road, was sent for, and upon his arrival he attended to the deceased until his death, which took place in about two hours after he was first found lying on the floor of his room.

§ Referred to above as the sponge bath. See first Note at bottom of page for more details.

Mr. John Bond deposed that he was an inspector of police, and that he made an examination of the dressing-room in which the deceased gentleman was found. The room in question was on the second floor, and upon entering it witness saw a flat bath in a corner of the room. At the bottom of the bath was a quantity of blood, and in that blood was discovered an open razor, that had evidently fallen or been thrown into the bath.

The coroner said that was all the evidence he intended to take at that meeting. He should, therefore, adjourn the proceedings until other witnesses could be brought before the court.

The inquiry was accordingly adjourned.

(p. 484) — London: John Campbell

Admiral Fitzroy, the well-known meteorologist, committed suicide on Sunday morning at his own house, Upper Norwood. He had overworked himself of late, found that he was losing his memory, became sleepless, and resorted to opium to obtain ease, which aggravated his symptoms. His doctor had warned him that he ran great risk of paralysis, but from a false tenderness did not at once compel him to give up labour. The Rev. F. Tremlett said the nervous condition of the Admiral had been a subject of conversation between himself, Captain Maury, and the deceased, and the witness had expressed an opinion that he was on his way to lunacy. The jury of course returned a verdict of temporary insanity.

We wonder to what extent death from over brain-work increases. The returns do not show it, but people who live in great cities hear of it with increasing frequency. It is worth recording that in the opinion of a very great physician § the true remedy for the sleeplessness which is the most distressing symptom of overwork is not opium, but Bass's beer, drunk at bed time, instead of at dinner.

§ The identity of the “very great physician” is unknown, pending further research.

(pp.788-789) — London: Sylvanus Urban, Gent. §

§ Edward Cave (1691-1754) first published The Gentleman's Magazine in 1731, sometimes writing under a Sylvanus Urban pseudonym. Apparently, the pseudonym was retained by publishers Bradbury & Evans who acquired the magazine in 1865.

Vice-Admiral FitzRoy

April 30. By his own hand, at his residence, Norwood, Surrey, aged 59, Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy, head of the meteorological department of the Board of Trade.

The deceased, who was born July 5, 1805, at Ampton Hall, Suffolk, was the youngest son of General Lord Charles FitzRoy, by his second wife, Frances Anne, eldest daughter of the first Marquis of Londonderry. In February, 1818, he entered the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, where he was awarded a medal for proficiency in his studies. On October 18, 1819, he was appointed to the “Owen Glendower,” then coasting between Brazil and Northern Peru. In 1821 he joined the “Hind,” and served two years in the Mediterranean. At an examination in the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, in July, 1824, he obtained the first place among twenty-six candidates, and was promoted immediately. In 1825, he joined the “Thetis,” and in 1828 he was appointed to the “Ganges,” and soon after flag-lieutenant at Rio Janeiro. In November, 1828, Mr. FitzRoy was made commander of the “Beagle,” a vessel employed in surveying the shores of Patagonia, Terra del Fuego, Chile, and Peru. In the winter of 1829, during an absence of thirty-two days from his ship, in a whaleboat, he explored the Jerome channel, and discovered the Otway and Skyring waters. On December 3, 1834, he was promoted to the rank of captain, but remained in command of the “Beagle,” pursuing his hydrographical duties, making surveys, and carrying a chain of meridian distances round the globe. During these surveys he expended considerably more than £3,000 out of his private fortune in buying, equipping, and manning small vessels as tenders, to enable him to carry out the orders of the Admiralty, an outlay which was not refunded to him.

Captain FitzRoy was elected an elder brother of the Trinity House in 1839, and sat in the House of Commons as member for Durham in 1841. He was appointed acting conservator of the [River] Mersey, September 21, 1842; and in the same year he was selected to attend the Archduke Frederick of Austria in his tour through Great Britain. He introduced a bill in Parliament in March, 1843, for establishing mercantile marine boards, and enforcing the examination of masters and mates in the merchant service. He went out as governor of New Zealand in April, 1843, and was succeeded in that office by Sir George Grey in 1846. In July, 1848, he superintended the fitting of the “Arrogant,” with a screw and peculiar machinery which gave [him] the utmost satisfaction.§ He became rear-admiral in 1857, and vice-admiral in 1863.

§ Apparently the work took many months: “The Arrogant, 46 [guns], new auxilliary screw steam frigate, will be commissioned tomorrow, for the command of Captain Robert Fitzroy (1834). She will, we believe, have a complement of 450, officers and men.” London: The Times, Wednesday, March 14, 1849.

When, in 1854, the meteorological department of the Board of Trade was established, Captain FitzRoy was placed at its head, and to him are owing the storm signals and other models of warning that are now in use for the benefit of the seaman. His own life, however, was the price of his devotion to his duties. For some time before his death he had suffered greatly from depression of mind, and had consulted his medical attendant, Dr. Frederick Heatley, who, perceiving that he was much reduced in health by the severe mental labours incident to his position, told him that he must rest from his labours for awhile, and only on the Thursday before his death [April 27] warned him that he must give up his studies, or the brain would become so affected that paralysis would ensue, but there was nothing in the tone of the Admiral's conversation that could lead to the supposition that he would commit suicide. On the day before his death he called on his friend, Captain Maury, the American navigator, who was about to leave for the West Indies, and his strange condition struck both that officer and a clergyman [Rev. Francis William Tremlett] with whom he [Maury] was staying. In the afternoon he [FitzRoy] went to London, returning in the evening. He retired to rest at the usual time, and on the following morning got up earlier than usual, and went to his bath-room. The family, finding that he remained longer than usual, knocked several times at the door, but receiving no answer, the door was at length broken open, when the Admiral was found weltering in his blood, having cut his throat. Dr. Heatley was immediately summoned, and on his arrival the Admiral was alive and recognized him, but he died soon afterwards. These facts have been deposed to by Dr. Heatley and other witnesses, the coroner's jury returned a verdict to the effect that [the] deceased destroyed himself while in an unsound state of mind.

Admiral FitzRoy was a Fellow of the Royal Society, of the Royal Asiatic Society, and many other learned bodies. He published—“Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of H.M.S. ‘Adventure’ and ‘Beagle,’ between the years 1826 and 1833, Describing their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the ‘Beagle's’ Circumnavigation of the Globe,” 4 vols. 8vo.; “Remarks on New Zealand,” 1846; and “Sailing Directions for South America,” 1858.

He was twice married, first in 1836 to Mary Henrietta, second daughter of the late Major-General O'Brien, which lady died in the spring of 1852; and secondly, in 1854, to Maria Isabella, daughter of the late J. H. Smyth, Esq., of Heath Hall, Yorkshire, who survives him. He leaves a son and two daughters by his first marriage.§

§ As elsewhere, his daughter Laura Maria Elizabeth by his second marriage, is not mentioned.

Of his personal character and devotion to his duties a distinguished officer§ thus writes:—

I knew poor dear FitzRoy from his boyhood; a more high-principled officer, a more amiable man, or a person of more useful general attainments never walked a quarter-deck; but having entered the Royal Navy after the general peace of 1815, his professional career was not remarkable, except for the zeal he displayed as a navigator and a nautical surveyor.

§ The “distinguished officer” remains unidentified here and elsewhere. Possibly, Admiral Plantagenet Pierrepont Cary (1806-1886). According to Mrs. FitzRoy's written account of his final days,§§ FitzRoy visited Cary several times between April 24 and 27, and as noted above, Cary was elected Foreman at the inquest following FitzRoy's suicide.

§§ Unidentified document, cited in John & Mary Gribbin's FitzRoy (pp 280-281).

The office over which he presided did not in itself entail any very extraordinany amount of intellectual exertion, but all his friends knew well that any subject the gallant officer touched received from him such an absolute amount of devotion, to prove, as he wished, that he fully executed the duties attached, that he worried himself with the details which belonged to his assistants, and thus made that which should have afforded pleasant recreation to the mind an intense labour.

It is true that the general duties of an office are supposed to be executed between the hours of ten and four during the day; but the individual who has his mind worried by the ever-changing conditions of the wind, electricity, and other warnings, which become part and parcel of the life of an observer of meteorological disturbances, cannot be said to be at any time truly quiescent. The whistle of the coming breeze, the rattling of windows, the pelting rain, lightning, thunder, and sudden change, either with or against the motion of the sun, as peculiarly noticeable in hurricanes, typhoons, or our own gales, all tend to keep up an excitement not to be understood by others than the workers in observatories.§

§ The above passage is perhaps not to be understood by anyone else either.

(p. 6) — Brisbane, Australia: Brisbane Newspaper Company Ltd.

SUICIDE OF VICE-ADMIRAL ROBERT FITZROY

On Monday morning a painful feeling of regret agitated the whole of the officials of the Board of Trade, on assembling at Whitehall, when the melancholy news of the suicide of Vice-Admiral Fitzroy, the chief of the meteorological division of that department of the Government, became known. He cut his throat at his residence, Lyndhurst-house, Norwood, on Sunday morning.

The unfortunate Admiral was the youngest son of the late General Lord Charles Fitzroy by his second marriage with Lady Frances Anne Stuart, eldest daughter of Robert, first Marquis of Londonderry. He was born on the 5th July, 1805; entered the navy in October, 1819, and obtained his commission as lieutenant in September, 1821. After serving on the Mediterranean and South American stations, he became, in August, 1828, flag-lieutenant to Rear-Admiral Robert W. Otway, at Rio Janeiro, and obtained his commission as commander in November the same year. He was employed as commander and captain of the Beagle from 1828 to 1836 in important hydrographical operations in South America and elsewhere, carrying on surveys and a chain of meridional distances round the globe. In 1843 he was appointed Governor of New Zealand, which appointment he held three years, being recalled owing to the disturbed state of the colony. Previously to going to New Zealand he was elected, in 1811, M. P. for the city of Durham.

Admiral Fitzroy's scientific researches in meteorology have procured him the highest reputation in that branch of science. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society, a Fellow of the Asiatic Society, and many other learned bodies. The late Admiral Fitzroy was twice married,—first in December, 1836, to Mary Henrietta, second daughter of the late Major-General O'Brien, which lady died in the spring of 1852; and secondly in April, 1854, to Maria Isabella, daughter of the late Mr. J. H. Smyth, of Heath-hall, who survives him. He leaves a son and two daughters by the first marriage [names given above]. The Admiral's only sister [Frances, 1803-1878] is married to Lord Dynevor.

(p. 5) — Maitland, Australia: Thomas William Tucker and Richard Jones

On Sunday, April 30, Admiral Robert Fitzroy, who resided at Norwood, and whose weather forecasts have rendered his name so famous, committed suicide. His daughter went upstairs, at a quarter-past nine o'clock, to ascertain if he was in his room. In a short time she came down stairs and said, “Papa is asleep; his door is locked.” A servant, named Whyman, then went upstairs to call him, but upon knocking at his dressing-room door, he received no answer. Mrs. Fitzroy was then sent for, and in her presence the room door was forced open. The door had been bolted from the inside. Upon entering the room the Admiral was found lying on his back in a large pool of blood. There was a deep gash in his throat. There was also a quantity of blood in the flat bath that was in the corner of the room.

Mr. F. Hetley, a doctor, was sent for, and upon his arrival at the house he attended to the Admiral until his death, which took place in about two hours after he was found. At the inquest on Monday the suicide was attributed to the brain of the Admiral having been overworked, to agitation induced by the reverses of the Confederates, among whom he had many friends, and to the assassination of President Lincoln. On Saturday he appeared more than ordinarily depressed, but not to a degree that would inspire fear of the awful occurrence which was brought about the next morning.

At the inquest, John Bond deposed that he was an inspector of police, and that he made an examination of the dressing-room in which the deceased gentleman was found. The room in question was on the second floor, and upon entering it witness saw a flat bath in a corner of the room. At the bottom of the bath was a quantity of blood, and in that blood was discovered an open razor, that had evidently faller or been thrown into the bath. At an adjourned inquest, on Wednesday, Dr. Hatley [sic], a friend of the Admiral's, said he entered the deceased's drawing-room before his death. “He was alive. He appeared to recognize me, but did not speak. I attended to him, and did all that was necessary. The nature of the injury was an incised wound, extending from the left side of the neck to the right ear. From the nature of the wound the instrument appeared to have been used more than once, although there was only one principal wound. The windpipe was so much severed that he could not speak.§

§ See note above about windpipe vs. vocal cords.

I had a knowledge of the deceased professionally from the 18th of April. On that day he consulted me with respect to his health. I was with him on that occasion about an hour and a half, and my deduction was that he was suffering from failing health in consequence of over-mental fatigue, which had brought on great depression of mind, and consequent wasting of the body. I was acquainted with his position and vocation. These were likely to induce great mental and bodily oppression. I also formed the opinion that he had a weak condition on the right side of the heart, and of that I informed him. On that occasion he asked me how he might continue his work with safety to his health and a view to his recovery, he observing that he had consulted me principally on that point. I gave him to understand that he should suspend his work temporarilly. He begged me to allow him to answer several letters that he had received. I told him that he had not the power at that time—meaning not mental power. There was apparently no acute disturbance of the mind at that time, but he was in a state that insanity might arise. On the 21st I saw him again. On that day I was sent for to go and see him immediately. He was then seriously ill, and I found him in a drowsy condition, resulting from a dose of opium he had taken to produce rest in consequence of a sleepless night he had had, following a most exciting day. I saw him frequently in the course of that day (the 21st), and on the following day he was relieved of the effect of the opiate. I saw him daily from the 22nd of April up to Thursday last. I am not aware that he did anything at all in the interval. In fact, I would have considered him at that time incapable of following his profession.

I had a long walk [sic, talk] with him on Thursday, but his mind was not in a fit state to bear excitement. He had called at my house on Thursday, and on his return from a walk I met him. We then spoke about his condition, and he asked me to give him a point blank opinion about it. I felt it was advisable to give him an answer. The opinion he asked was whether he should give up his work or not. That was always the question he put to me. My reply was that he was quite incapable of carrying it on, and if he attempted serious consequences would arise, and that the result would be a condition of the brain that might lead to paralysis. He said he was grateful indeed to me for telling him so, for it might save his life. When I last saw him on Thursday he was better than he had been a few days before. He was, however, in his usual depressed condition, which was always the character of his malady. From the conversations I had with him the idea of his committing suicide did not enter into my mind — Mr. F. W. Tremlett said: I first heard of his death on Monday. I had been with him on Saturday. He was at my house on that day, and also on the Wednesday or Thursday previously; he remained an hour and a half. He often came to see me. He came also to take leave of Captain Maury, who was about to proceed to the West Indies, and who had been a personal friend of the deceased from many years. Both Captain Maury and I had a conversation with him about the state of his health. Maury said, “Fitzroy, you want dynamic force,” alluding to his nervous state, and meaning by that expression nervous power. The Admiral turned to me, and said he wanted to have my opinion. I replied that I quite agreed with Maury. The Admiral asked on what ground I had formed such an opinion. I replied, “You know you cannot make up your mind on any subject.“ He said, “It's quite true: I cannot.” I said, “Your nervous system is unstrung; I see it by the twitching of your hands, and I judge from what you yourself have told me.”

He said he was affected with noises in the ears, and was generally unable to sleep at nights. I replied that those were alarming symptoms in his condition. I urged him to resign at once his post as meteorological office of the Board of Trade. I had had many conversations with him before upon that subject. I had also many opportunities of judging of the nature of his avocations, and I know they were more laborious. He left my house before Captain Maury left, and after he had gone I remarked to Maury upon the Admiral being in a bad way. I added, alluding to Maury going away from the country, “My opinion is that you will never see him in his senses again.” I had often thought that he would become deranged. The jury returned a verdict that the deceased had destroyed himself when in an unsound state of mind. Rear-Admiral Robert Fitzroy was the second and youngest surviving son of the late General Lord Charles Fitzroy (who died in 1829), by his second wife, Lady Frances Anne, eldest daughter of Robert, first Marquis of Londonderry, and cousin of the late Duke of Grafton. He was born in June, 1805. The late Admiral married, in 1830 [sic, 1836], Mary Henrietta, second daughter of the late Major General Edward Jas. O'Brien, by whom he has left issue.—Liverpool Albion.§

§ Again, FitzRoy's second marriage is ignored. See The Times obituary above for details.

(May, pp. 471-472) Eliakim & Robert S. Littell

Over-Taxed Brains

Human life is in many respects worth more now than it was a hundred years ago. We no longer, as a rule, eat and drink to excess as our ancesters did; we do not invite apoplexy by covering our heads with a cap of dead hair, and swathing our throats in folds of unnecessary linen; our sanitary arrangements are a hundredfold better, and our town-dwellers see much more of the country, and taste much more of the country air. Yet it is certain that nervous disorders are greatly on the increase, and it is to be feared that the excitement of modern life is introducing new maladies while removing old. A physician of the early or middle Georgian era said that a large proportion of the deaths of Englishmen was due to repletion. The proportion under that head is now very much less; but what we have gained in one direction we have lost in another. Among the intellectual and mercantile classes of the present day, the greatest danger to life is from nervous exhaustion. We make too serious and too incessant demands on the most delicate part of our structure, and the whole fabric gives way under paralysis, or heart complaint, or softening of the brain, or imbecility, or madness. Disease of the heart is constantly sweeping off our men of intellect, and the vast size of our modern lunatic asylums, together with the frequent necessity of adding to their number, is a melancholy proof of the overwrought state of a large part of the population.

The lamentable suicide on Sunday of Admiral Fitzroy brings us face to face with the depressing fact that modern civilization is a brilliant but a relentless despot, to whom, in some shape or other, our foremost men are called upon to render up their lives. The evidence given at the inquest brings out the pitiable story with only too great clearness. At sixty years of age, while still preserving the external appearance of a man ten years younger, he who had saved so many lives from the perils of the deep, was brought to that pass of profound mental wretchedness and depression that self-inflicted death seemed the only haven of relief from the sheer misery of being. It is, perhaps, not unworthy of note, that Admiral Fitzroy was a near relative of the famous Lord Castlereagh, who committed suicide in a very similar manner. It may be, that there is a tendency to this form of insanity in the family, since it is well known that such a predisposition may lurk in the blood, and reveal itself from time to time in repeated acts of self-murder. But it is more probable that, in Admiral Fitzroy's as in Lord Castlereagh's case, the origin of the suicidal madness is to be traced to brain-disturbance resulting from over-work. The Prime Minister gave way under the toil and responsibility of guiding such a country as England through one of the most difficult crises of her history—a task rendered the more difficult by the unpopularity of his acts among the masses of the people. The scientific man has been worn out by the weight of continual cares resulting from his post as meteorological officer of the Board of Trade. Both succumbed to demands which they had probably not the physical strength to answer beyond a certain point. In the case of Admiral Fitzroy, we see laid out before us on the inquest all the steps by which the melancholy result was reached.

He had been a handsome man, with a fine, vigorous presence, a genial manner, and an amiable disposition. With the accumulating pressure of his work—which, it should be recollected, involved calculations of the utmost nicety, whereon the safety of many lives depended—he became depressed in spirits, peculiar in manner, reduced in person. He acquired that terrible inability to sleep which is one of the most dreadful of those means by which Nature avenges the abuse of the mental powers; and he was forced to take opium at night—at one time to an extent which threatened serious consequences. The right side of the heart became weak in its action; the brain showed symptoms of paralysis; his medical attendant § dreaded the advent of insanity, and warned him that he must refrain from work; his servants noticed that he gave strange and inappropriate answers to questions; his friends remarked that he could not make up his mind on any subject, which he admitted to be the case; he had noises in the ears and twitchings of the hands. His intimate friend, Captain Maury, told him that he “wanted dynamic force,” meaning nervous power. In other words, the subtle organization of nerves and brain was worn out, or, perhaps we should rather say, plunged into a state of abnormal and terrible excitement, in which the perceptions became confused, and nothing remained clear but the pain and hopelessness of life. Then the desperate hand was raised against its own existence, and we read the termination of the story in the verdict of “Temporary Insanity.” And much the same story must, doubtless, be told of the other suicide of the week, Mr. W. G. [William George] Prescott, the banker.§§

§§ One day before FitzRoy, Prescott locked himself in his room and cut his throat with a razor.

That men of intellect are peculiarly liable to mental disease might be safely supposed, without any direct evidence, from the very nature of intellect and the work it has to perform. Genius, whether it exhibit itself in literature, art, or science, is the result of a peculiar fineness and sensitiveness of the nervous system, without which great men would be nothing more than ordinary men, and having which they are often martyrs as well as conquerors. The possession of this delicate and subtle framework enables them to perceive what others would pass over; but it also lays them open to shocks and jars of which the more robust would not be conscious. Too often in the end, if not in the beginning, genius, as a witty French author§ once said, “is a disease of the nerves.” The brain becomes unnaturally sharpened, and eats into itself. The whole physique suffers from the undue strain on its most exquisite part. The ethereal spirit that sits within this mesh of nerves, and arteries, and fibres, suffers with the suffering of that marvellous mechanism on which it is dependent for its earthly existence.

§ Jacques-Joseph Moreau; although hardly witty, he was a French author. In the July 16, 1864 issue of The Athenæum, in an unsigned review of Émile Deschanel's Physiology of Writers and Artists (pp. 76-77), the reviewer notes that “The Doctor [Moreau] … comes to the conclusion that genius is a disease of the nerves.”

The same week in which we hear of Admiral Fitzroy's suicide brings us news of General Kmety§ expiring, prematurely old, at fifty. Swift dying in moody mania— Sir Isaac Newton with intellect temporarily shattered—Johnson oppressed by thick-coming fancies—Cowper overcome by them—Sir Walter Scott excited to such a pitch of mental activity, that he “could not leave off thinking,” and moved about among familiar scenes with a sense of ghostly unreality—Southey struck down from his height of literary fame into mere imbecility—Auckland smitten in his strength—Laman Blanchard, [Benjamin] Haydon, and Hugh Miller perishing by their own hands.§§

§ Hungarian General György Kmety.

§§ The others listed in this paragraph of course did not die in the same week as FitzRoy, a point not made clear by the wording. In fact, two paragraphs earlier, the notice mentions “the other suicide of the week.”

These are only a few instances of that fate which so often overtakes men of unusual powers. And to these must be added several cases occurring of late years, in which, without the mind being at all affected, our prominent statesmen, such as Lord Herbert and Sir George Cornewall Lewis, have died prematurely from exhaustion. The fact is that much is expected from those to whom much has been given. They become committed to work which cannot be divided, and they fall as much in the service of their country as though they had perished on the field of battle or the sinking deck.

Notes

In most circumstances, death by slashing the throat occurs within minutes, and certainly the suicide victim would not remain alive for two hours or more. But in the Maitland Mercury report above, the “lying … in a pool of blood” and “also blood in the flat bath” indicate two locations: apparently FitzRoy slashed his throat while in the bath, and then for reasons unknown, climbed out and collapsed in the room, something that would have been impossible if he had been more thorough in doing the deed. So, is it possible he had a last-minute hope for survival and was making his way to the door to seek help? Unfortunately, he took the answer to his grave, and we shall never know why he was found on the floor and not in the bath. Of course, the size of that bath is unknown, but the razor and three pints of blood it contained suggest it was indeed a larger floor-standing device. Furthermore, Dr. Heatley's remark that he saw FitzRoy “ … lying on his back, with his head close to the sponge-bath on the floor” (emphasis added) also supports this supposition.

To add yet another mystery, in his FitzRoy of the Beagle biography, author H. E. L. Mellersh includes FitzRoy's wife's account of his final days, taken from “Private papers in the possession of Robert FitzRoy's descendants.” The account concludes (p. 284) with:

He got out of bed before I did and went to his dressing room kissing Laura as he passed§ … and did not lock the door of his dressing-room at first. [Emphasis in original, as noted in Mellersh's text, but not in Gribbins'].

§ How FitzRoy's widow knew of this is unknown. Perhaps Laura told her about it later on.

In context, it would appear Mrs. FitzRoy was contradicting something stated elsewhere in the private papers. But, if he got up before she did, and the door had to be forced open (as described above), how would she know that he did not lock the door at first?

Perhaps her remark was the source of author Nick Hazlewood's account of FitzRoy's final moments; he writes, with some embellishment:

In his dressing room he closed the door without locking it, took out a razor, held it up and then, in a deliberate arc, slit his throat.§

§ Savage: The Life and Times of Jemmy Button (p. 337). 2001, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin's Press.

At the time of his death, the age and location of FitzRoy's living children were:

| Name | Age | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Robert | 26 | a lieutenant in the Royal Navy |

| Fanny | 23 | Since the 1852 death of their mother, both sisters lived with the family of FitzRoy's brother George § |

| Katherine | 20 | |

| Laura | 7 | living with her parents, as already noted |

§ But in the unidentified document cited above, Mrs. FitzRoy gives evidence that FitzRoy's eldest daughters were living with (or, just visiting?) the couple on the day before his suicide:

After luncheon he felt somewhat better, and set out to take a walk with the two eldest girls. … When the girls had gone to bed, he said to me he wished to talk over with me about his idea of going to London on Sunday to see Maury once again.

And as noted earlier, the presence of his two (actually, three) daughters was also noted in the May 4, 1865 obituary in The Times.

To conclude with a final mystery, in her 1934 “Foreword” to Mellersh's FitzRoy of the Beagle mentioned above, Lady Barlow wrote:

I remember well the look of [Laura FitzRoy's] crowded Victorian drawing-room, dominated by a large white marble bust of her father. … I asked Miss FitzRoy [now, age 76] tentatively whether the bust had ever been photographed? And I remember how her brisk answer was unequivocal and final: “No, I should not like the idea at all.”

Almost a decade later, Miss FitzRoy bequeathed the bust to the Royal Meteorological Society, where Society Journal editor E. L. Hawke noted that it was placed in the main library room at the Society's Cromwell Road headquarters. He also mentioned receiving “a gilt-framed crayon portrait of the admiral at the age of 30, when he was in command of the Beagle.” The Society has moved several times since then, and both the bust and the portrait have gone missing. There is however a plinth from a broken statue in storage at the Society's current home in Reading. Is this all that remains of the FitzRoy bust? If so, it is indeed odd that someone would go to the trouble of saving just the plinth but not the rest of it. And surely FitzRoy would have been famous enough to have warranted a written record of a damaged white marble bust. As for the crayon portrait, did it find its way into someone's private collection? For now, we have no definitive answers to these questions. And unfortunately, Miss FitzRoy's wishes were apparently honored even after her passing; we have no photographs of either work, and can only hope that one day they will be re-discovered intact.