A Social Visit Extraordinary

Ernest G. Reimer

It was an hour and a half flight in our small single-engine plane, and the strange history of Floreana Island reviewed itself in my mind as we flew through the equatorial haze that cut visibility to a minimum.

It was in 1929 that Dr. Ritter, a middle-aged Berlin dentist, and Frau Dore Koerwin, the wife of a gymnasium instructor, left civilization behind them and came to Floreana to establish their new home. Their attempt to live a life apart from the world drew much publicity; that plus the fact that Dr. Ritter had all his teeth pulled and a false set of stainless steel ones made. A short time afterward they were joined by another German couple, the Wittmers, who had a half-blind son in his teens. The two families set up their homes on the four-hundred square miles of Floreana far enough apart so as not to interfere with each other.

Their life of contentment was rudely interrupted in 1932 when the so-called Baroness Eloise Bosquet de Wagner Wehrborn arrived on the isle with her two male companions, Alfred Rudolf Lorenz, her lover, and Robert Phillipson. Her plans were to make the Galapagos Islands a world-famous resort and she settled on Floreana near the Wittmers.

Promptly upon her arrival she set herself up as the Empress of Floreana and, clad in a brassiere and shorts and with a pistol, she began her despotic rule. The Ritters and Wittmers were allowed to remain but all other intruders were rashly dealt with. Rumors tell of her shooting and even killing people, but these are questionable. A honeymoon couple cast adrift in a small boat from another isle landed on Floreana; the Baroness refused them aid and forced them out to sea again. She was also noted for shooting animals and then nursing them back to health.

Lorenz, the smaller of the two men, was her favorite but soon she began to play Phillipson off against him. There were supposed to have been daily duels between the two men for her favor; these duels she encouraged and watched with great delight. Lorenz was no match for the larger Phillipson and he was ousted completely as the Baroness' lover. His lot now became that of servant—rather, that of a slave. He had to do all the hard work around the place, and if he faltered or hesitated he suffered beatings and humiliations from Phillipson and the Baroness. Lorenz occasionally stayed with the Wittmers while recovering from these beatings.

This state of affairs lasted for two years. It was on or about March 28, 1934 that the Baroness and Phillipson disappeared. Lorenz said they had gone off on an American yacht, although no yacht had been reported in the vicinity for some time. Now Lorenz wanted to leave as fast as possible, so he left a note in the mail barrel in Post Office Bay asking to be taken off in the first boat that stopped there. A Norwegian fisherman from Academy Bay on nearby Santa Cruz, Nuggerud, stopped at Floreana on one of his periodic calls and when he left Lorenz went with him. On arriving in Academy Bay Lorenz, very anxious to catch the steamer leaving San Cristóbal Island soon for the mainland, persuaded Nuggerud to ferry him over. They left for the island on July 13th but never arrived there.

It was several months later that a small American fishing boat passing the island of Marchena, about 150 miles north of Santa Cruz, saw something on the shore. They investigated and found the wreckage of a small rowboat; halfway under the boat lay a human body. Nearby was another corpse, partially covered with some clothes. Both bodies were badly decomposed. The remains of a seal and iguana, a small pile of burnt paper and some matches all contributed to a tragic story that told itself. Near the bodies were found some mail from Academy Bay and Floreana and also the German passport of Lorenz.

In this stormless area it is hard to imagine what had happened, but Nuggerud's boat was noted for its erratic behavior. It probably broke down again and they drifted for days and finally landed on waterless Marchena, there to slowly await a death of thirst and hunger.

The mystery of the Baroness and Phillipson has never been solved; many possible solutions have been offered but none proven. The common theory was that Lorenz, refusing to take any more from these two, had killed them. It would have been easy with the rocky features of Floreana to hide the bodies or perhaps the ever-present sharks solved that problem for him.

Dr. Ritter died a natural death on the island and Frau Koerwin soon returned to Germany.§ The Wittmers were still on the island and it was they that we intended to visit. We had flown over their place many times and there was always someone to wave a cheery hello. The family now numbered five; a boy and a girl being born on the island. Captain Vernon W. “Fox” Lange, a tall, rangy Minnesotan, and I decided to take a small plane to Floreana and see if we couldn't land in a pasture near the Wittmers and pay a social call.

§ Actually, Ritter died of food poisoning, as described by Heinz Wittmer in the Meat Poisoning section of What Happened on Galápagos.

Soon the outline of Floreana broke through the haze and Lange, who could fly like Menuhin could play, expertly guided the plane between the hills and over the trees towards the Wittmer farm. As we flew over their place we were again greeted by three members of the family. We continued past their place and descended onto the pasture; as we flew over it at about five feet we both could see rocks covering the field. These rocks ranged in size from small pebbles to some that were six inches in diameter. Fox made several passes at the field locating the best landing strip; as we had no interphone communication it was my difficult task to just sit and watch. Finally on the fifth pass the wheels hit and the plane rolled to a stop within two hundred feet. As we crawled out of the plane we exchanged smiles of relief. Positioning the plane for take-off and securing it well we started off in the general direction of the Wittmers. We had to climb and go around a hill covered with high underbrush. The hot morning sun beat down and the difficult going through the brush soon left us wet with perspiration. The branches and vines caught at us and, in the extreme quiet of the morning, it seemed as though they had taken it upon themselves to bar the way. There seemed to be no life here at all, and the eerie atmosphere kept us close together as we forced our way onwards. The going was hard and we stopped frequently to catch our breath.

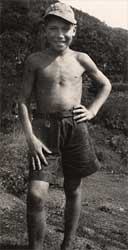

After a hike of approximately thirty minutes the ground began to level off; we had reached the top of the hill and were only a short distance from the Wittmers. The underbrush was thinning out now and soon we came to a stone fence. On the other side of the fence was the dry bed of a once-small stream. Across this, nestled against the side of the hill was the home of the Wittmers. Save for a bird or two and the sound of the gentle wind through the trees there was no movement, no noise at all. Lange and I looked at each other and wondered about the correct etiquette of a call such as this. We decided the best thing to do would be to holler from this side of the fence. We yelled our greeting and immediately some dogs began barking and from around the corner of the house came bounding two huge police dogs. They were followed by a boy holding a rifle, with what at that moment did not look like a friendly expression on his face. The boy stood there, rifle in his hands, a dog on each side, their barks and growls resounding throughout the stillness; this, however only lasted a moment for Mrs. Wittmer then appeared and with a welcoming smile and outstretched arms bade us enter. We climbed the fence, crossed the dry bed and came up to the house.

“Welcome, welcome.” she greeted us, “We were just wondering if you had really landed. You only flew over us once and we thought that maybe you would land. Rolf here wanted to go down and see but I told him to wait a bit. Come in, come in, it's so good to see someone again.”

We introduced ourselves and, in turn, met her two children, Rolf of the rifle, age 11 and Floreanita, a pretty little girl of seven. Both children were extremely well mannered, polite and intelligent. They were dressed in home-made but well-made clothes. As Mrs. Wittmer led the way into the house she sent the boy to fetch his father from the farm.

We introduced ourselves and, in turn, met her two children, Rolf of the rifle, age 11 and Floreanita, a pretty little girl of seven. Both children were extremely well mannered, polite and intelligent. They were dressed in home-made but well-made clothes. As Mrs. Wittmer led the way into the house she sent the boy to fetch his father from the farm.

Their home was in the shape of a small rectangle; the kitchen and dining room each comprised one quarter of it and the other half consisted of bedrooms. On the hill side of the house the hill itself formed half of the wall and the other three walls were constructed of large stones. The floor was packed earth and the whole place, while small, gave the appearance of very comfortable living.

Mrs. Wittmer, and when he appeared, Mr. Wittmer, were both enthusiastic in their welcome. We were the first vistors they had had in six months and our news of the outside world was received gratefully. They had no radio or newspaper and this seemed to be the only thing they missed. We spent some time in bringing them up-to-date on world events.

We met all the family except the eldest son, whose bad eyes prevented him accompanying his father from the fields. The first thing that struck us about these people was the excellent health they seemed to enjoy. Their life of isolation no doubt had its disadvantages, but good health certainly made up for a lot of them. We asked what they did in case of sickness and they replied that they had thus far been able to handle anything that came along. The conversation turned to the children and Mrs. Wittmer explained that she had no trouble at their birth and that both children had enjoyed good health all their lives.

That the children's education had not been neglected was very evident as we observed them. Their parent's plans called for the children to be formally educated in England at the war's conclusion and I believe that these two will have a head start on any other children of their own age. Their self-reliance and assurance were remarkable for their age. The island had many wild bulls that were a nuisance and sometimes destructive on the farm; it was Rolf's job to kill these bulls and he considered it a poor one unless he placed the first bullet between the bull's eyes. Mr. Wittmer in one of the photos wears an apron made from the hide of one of these bulls.

Mr. Wittmer produced a bottle of lemon-colored, home-made punch; the taste was indefinite but along the wild plum line. It was delicious and we questioned him as to its contents. His only reply was that it was a combination of fruit juices. As we were conversing with Mr. Wittmer, his wife was busy preparing some coffee and cake and it was hard to realize that we were hundreds of miles from civilization; in their solitude through the years the Wittmers had maintained a perfect mode of living. They could return and at once fit into any small community. When we learned that their only contact with the outside world was an Ecuadorian boat that stopped at inconsistent intervals, sometimes not for months, it increased our amazement.

Their source of fresh water was a small stream in a cave behind the house and they had rigged up a half-inch pipe that caught the free-falling water and carried it directly to the kitchen sink. One of the husband's hobbies much have been that of carving smoking pipes; he showed up about eight of them in a beautiful hand-carved pipe stand.

They subsisted almost entirely upon their own products; the boat bringing them whatever the land could not furnish and as we marveled at the completeness of their life they told us of the long time it took to accumulate their belongings and of the difficulties they encountered the first few years. The method of communication was still the mail barrel in Post Office Bay, where a letter was deposited until a passing boat picked it up; it was in this manner too that they received their mail.

We questioned them about the past and they were very pleasant in their answers but were reticent to speak about the Baroness, so we did not press the matter. Mr. Wittmer pointed out where the Baroness had her home, just across a small valley.

We wanted to take some pictures of the family and their home, so we went out to their front yard. Here, growing in abundance were many beautiful wild flowers of every description and color. There were many baby chicks and ducklings running about the yard and along with the dogs, chickens and geese it paralled many a scene on an American farm.

We wanted to take some pictures of the family and their home, so we went out to their front yard. Here, growing in abundance were many beautiful wild flowers of every description and color. There were many baby chicks and ducklings running about the yard and along with the dogs, chickens and geese it paralled many a scene on an American farm.

On the path leading down to the fields there was a little knoll and from here Mr. Wittmer pointed out his farm lands that were visible from this point. We did not have time to go down and see the manner and style of his farming, but judging from what we had already seen I'm sure it lacked nothing.

The knoll was perhaps three hundred feet from the house and yet as we looked back we had difficulty picking it out for it blended in perfectly with the background. Other than a red roof section or a yellow window curtain, there was nothing to indicate a modern eden.

We asked them if they were happy; if being free from all the limitations that society imposes and therefore doing without the benefits of society brought about a philosophy resulting in a life of contentment. The smiles that came to their faces showed that they had been asked this many times before and I imagine we got the same answer as the rest. A shrug of the shoulders and a smile that said, “look for yourself.” They had been there for fifteen years and although the war worked its hardships on them in a more severe way than the rest of us they never once left their isle. They might not have the complete answer but I think they have come a lot closer to it than the rest of us.

The time slipped away much faster than we realized and we had to say goodbye to this extraordinary couple. We promised to send them copies of the pictures we took of their children and Rolf and Floreanita were sent along to guide us down the path to the field where we had left our plane. I can still see Rolf, rifle in hand, striding manfully down the trail ahead of us. I don't believe his rifle was ever more than a few inches from his grasp.

The time slipped away much faster than we realized and we had to say goodbye to this extraordinary couple. We promised to send them copies of the pictures we took of their children and Rolf and Floreanita were sent along to guide us down the path to the field where we had left our plane. I can still see Rolf, rifle in hand, striding manfully down the trail ahead of us. I don't believe his rifle was ever more than a few inches from his grasp.

The airplane was something completely new to these two children, for we were the first ones ever to land on Floreana; they had seen planes in the air but had never been close to one on the ground. We let them inspect the plane as much as they wanted and even placed Rolf in the cockpit, but the usual childish enthusiasm for airplanes was lacking. Both of them were very quiet as they looked at this man-made contraption; it did not register with them. Its many gadgets, dials, switches and levers were too much and bewilderment showed on both faces. We told them to stand about two hundred feet away and watch us take off. They obeyed in silent acquiescence, but as soon as the engine caught and started with a roar both kids turned and ran as fast as they could to the shelter of the trees. There they watched us taxi and take-off with perhaps more confidence.

As we flew back towards our base with its electric lights, movie shows, radios and all the other things we would feel lost without, I wondered who was better off, they or we.

Ernest Reimer at Floreana