The Last Cruise of the Schooner Chance

Jacob Lundh

1950: The schooner Chance anchored at Sulivan Bay, Isla San Salvador.

Baltra

If you ever visited Guayaquil, Ecuador's main port, in the early 1950s, maybe you would see the schooner Chance lying on her side, sunken in the mire of the Guayas River, across from the city. I never saw her myself in that condition, as I did not return to Guayaquil until some years later, but I have heard that it was a sad sight to see the old yacht, almost covered by the muddy waters of the wide, great, lazy river.

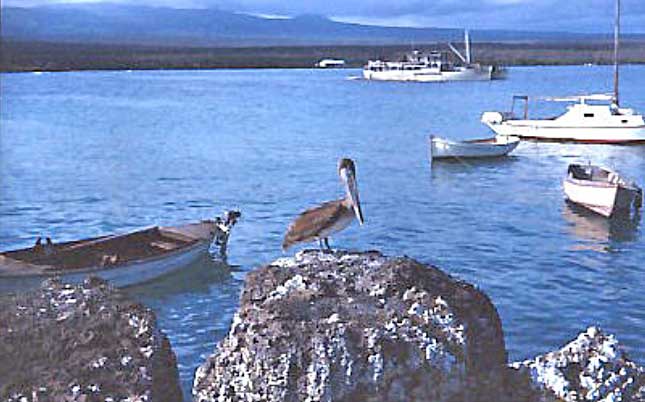

The anchorage at Aeolian Cove on the southwest side of Baltra. The dock was built by the Americans during WWII.

She was a proud ship with her sleek 78 feet of over all length, and her lofty masts, as she raced before the trade wind, all her canvas swollen, her bow breaking the deep blue waves into snowy foam. Her last owner, Captain Larry Blanc, told me when we were on what would be her last cruise, in 1950, that she was then twenty-four years old, and had been three times around the world. But let me get started on that last cruise, which was made in May of 1950, when we sailed her among the Galápagos Islands.

Captain Blanc had been in contact with some Germans who lived on the Island of Santa Cruz, the second largest of the Galápagos. From them he had received much enthusiastic but mostly misguiding information about conditions in the islands. Behind it all was their desire to have him bring out a vessel that was capable of making voyages between Galápagos and the mainland. They also planned to fish with him, producing salted dried fish.

At that time, communications with the mainland were very irregular and depended largely on Ecuadorian naval transport ships that offered unsuitable accomodatins for the passenger and inadequate cargo facilities. However, when Captain Blanc finally arrived, after much delay and some difficulties in Mexico and a stop at Cocos Island, he was coldly received by his friends, who now chose to forget everything they had written him. Furthermore, they even provided employment for their friend's crew, leaving him alone with his schooner.

Still, the captain decided to look around the islands, and find out for himself what they had to offer. He talked four of us Santacrucians to join him on his planned cruise. Thus, on the morning of May 13, 1950, before daylight, we were all awakened by his loud and cheery shouts, followed by his orders to get into action. We went on deck all of us, except one who stayed behind to make breakfast.

I doubt if any of us was inclined to share the skipper's good mood, for it was cold - at least for our tropicalized blood - and slumber is at its sweetest at that time of the morning. Still, we went at it with all our strength, for we had a hard time pulling up the stern anchor, on top of which had anchored a ship from Guayaquil, which made it necessary to pull it up from aboard, instead of doing it from the pram, by pulling it by the rope that held it to a buoy we had placed over it. The bow anchor was a different matter, for we fastened a piece of balsa wood to its chain and threw the whole over the side, to use as a mooring upon our return.

As I had spent about ten months on the mainland, living a civilized life, my callouses were all gone, so my hands became very sore and red with all the rope pulling. But it felt good to be under way, with the engine going and the sails up. It also felt good to go down to the main cabin and get our breakfast, which was served by the hook-nosed, piratical looking skinny Norwegian who had prepared it. This fellow, Erling, had grown up on the island, and belonged to one of the two families who had arrived to Galápagos in 1935. They would call themselves “pioneers” though people had been living on the island a number of years before them.

The other members of our group, besides Erling and the captain, were Miguel Castro, the son of an Ecudorian sea captain who had retired with his family to the island, and my brother Eric and I, whose father was also a master mariner who had sought peace and a good climate on the Galápagos.

Captain Blanc sang all day long, danced on deck and was extremely happy to be out at sea again. I shared his exhilaration fully, but did not express it as eloquently as he. Of course, some of my good mood vanished as I headed for the galley. It was my turn to cook that day, though Erling had made breakfast. However, the day was glorious, the kind of day that makes you feel like hoisting sails to race out across the green lagoons and out to the blue ocean with its whitecaps. Sunshine lit up the sea and the island, as we followed its southeastern shore with its low lands and tiny shallow bays. The breeze was strong and steady despite its being the warm season when the winds are fickle and unsteady.

And sail we did! Most of the way up to Baltra Island was done by sail alone, the Chance lying down on her side, water splashing on her deck as she raced over the sea, up towards Gordon Rocks, off the eastern coast of Santa Cruz. Here, across from the Rocks the land starts to rise again until it forms cliffs which run the remaining length of the eastern coast, tunrning around along the northern end of the island and ending almost immediately on entering the Canal de Itabaca, which separates Baltra from the north coast of Santa Cruz.

While canvas and wind pulled us along at a record-breaking speed, I made my acquaintance with the galley. It was fairly spacious, and a very refreshing breeze came down through the hatch overhead, which in that warm climate was a decided advantage, especially with a wood burning stove heating up the enclosed space.

My next move was to locate our supplies so that I could find what was needed for the cooking. I headed astern, into the main cabin, crossed it and reached the port stateroom, where the double berth and the floor had been used to store some of our supplies - bananas, plantains, potatoes, oranges, limes, etc. In the starboard stateroom I found, on the berth, our flour, sugar and rice. This latter cabin gave access to the large and well ventilated engine room.

Now, knowing where to find what was needed, I returned to the galley with the intention of starting the job ahead. But there was some excited shouting on deck that sent me first up there. A skipjack had been caught, so we would have fish for our next meal. Unfortunately, this lone skipjack would be - strange to say - the only fish we caught on our whole cruise. This negative experience made me wonder what had become of the “sea boiling over with fish of all kinds” as described by visiting tourists and newspapermen when they recall their supposed experiences from the islands.

Somehow, we must have felt the importance of this catch, for we all took turns to pose for pictures taken with it, Miguel Castro doing the photographing. After this formality, the fish was solemnly handed to me, and we both disappeared down below, while I wondered how to prepared the mortal remains of that member of the mackerel family. Once, in the galley, I heard something shouted to me from deck. Looking up through the open hatch, I shouted back a question to find out what it all was about. Nobody replied.

But I found out soon enough. The ship turned over on the opposite tack very abruptly, sending me down on my behind. Before I quite realized what was going on, two caceroles, fortunately empty, landed by my side, and the skipjack flew across the galley, giving me in passing a wet and slimy slap in the face. The din made by the flying pots, pans, lids and other kitchen parephernalia was heard all over the ship, so it was not strange that our skipper should show his head through the hatch to ask me if anything had happened to the chinaware. Reassured that it was still in its place and undamaged, he grinned and disappeared. While I touched a lump that had appeared on the back of my skull, I was more hurt by his lack of interest in my personal wellbeing, giving all his priorities to the chinaware.

The change of tack had been due to our turning around the northern part of Seymour, after passing the cliffs that form the inaccesible eastern shores of the latter and Baltra. Both these small islands are high on the east side, becoming gradually lower as they descend towards the west, where they both have beautiful white sand beaches backed by low land that rises inland to form flat plateaux and vertical cliffs that end abruptly at the sea to the east.

First sailing west and then turning south, we raced down towards Aeolian Cove, formerly known as Birs Cove, on the southwest side of Baltra, where the Americans had their main Galápagos base during the war. Here, we anchored on a sandy bottom, across from the dock that had been built for the base. The cove opens to the west, and the dock is on its northern shore. There is a large sandy beach at the head of the cove, where the Santa Cruz fishermen used to camp before the base was built.

In those pre-war days, people visited the island to catch the then abundant wild goats. They would chase the animals towards the cliffs, cornering them there and catching them alive. In fact, the tame and wild goats on Santa Cruz had originally been brought from this smaller island. These visitors were mostly fishermen from Santa Cruz, who camped on the beach while catching groupers in the neighboring waters, salting them and drying them for export to the mainland. Running after goats was not difficult on Baltra, as the vegetation was rather open and the inland terrain fairly level. Most of the vegetation consists of scattered cacti and palosanto (Bursera ) trees, grasses and small plants making up most of the minor ground cover. There is the interesting fact that the bursera trees of Baltra, neighboring Seymour and the offshore islet of Daphne minor belong to a different form or species (Bursera malacophylla) than the same trees on the other islands (B.graveolens). The latter is the same species that is found on the mainland.

It always made me sad to look at the landscape on Baltra. Only the mangled remains of the island survive, after being wounded by the work of the bulldozers and other machinery. Roads run all over the place, and at the time barracks stood in small groups everywhere, while poles for supporting the wires of the electrical installations outnumbered the cacti. The worst of all was the emptiness of the place, with the goats extinct and the people gone. Everything seemed to be dead, except for the wind. The wooden barracks deteriorating in the hot sun, made me think of the futility of man's life and his works.

However, later in the same decade the Ecuadorian Government, seeing that it would be too expensive to maintain all the barracks, let the settlers dismantle them and use them for building houses on the inhabited islands. Thus, in the late 1950s “Baltra pine” became the main building material for houses in the Galápagos.

We had barely anchored, when a truck raced down from the old navy base, stopping at the dock. When we landed, we discovered aboard it the port captain, Lieutenant César Crespo and his second in command, Chief Petty Officer Erazo, a navy mechanic. They were in charge of a garrison of half a dozen men. There were also two women on the island, the wives of the lieutenant and Mrs. Erazo. Two mongrel dogs completed the naval garrison. We were received cordially enough, though with some reserve. However, learning of Miguel's identity, Lt. Crespo adopted a somewhat paternal attitude towards him, as he happened to be an old friend of our companion's father.

We were invited to ride up to the base on the old truck. The captain of the port regarded me with considerable interest, as I switched back and forth between Spanish and English while helping him and Captain Blanc to communicate. I am sure he was intrigued by my decidedly Guayaquilian accent, beside my very foreign appearance with my blond hair and gray-blue eyes. Erazo seemed equally intrigued.

On the way up to the base, the skipper and I held a small private discussion. He had hidden under his matress a bottle of excellent rum, and he wondered if it was fit or not to use it to make the port captain more friendly. It was decided that it would be proper to share the precious bottle with our new friends, so I was taken down to the dock again to go aboard to fetch the bottle. At the dock, we met with two navy men and one of the dogs, a bitch called Baltra that was later taken to Santa Cruz. They all, including Baltra, wanted to go out to the yacht, but we left the dog on the dock, as Blanc disliked having children and animals on his immaculate ship.

As we rowed out, Baltra stood on the dock howling dismally, then ran along the edge all the way to the end, from where she jumped into the sea and swam after us. There was a stiff breeze blowing, so the animal had no trouble in overtaking us. We pulled her aboard, she shook water all over us, and finally lay down in the bottom of the boat. Once out on the schooner, she was tied up on deck to prevent her fleas from joining the crew of the Chance, and her wet paws from leaving marks down below.

The two enlisted men were interested in cigarettes. The sight of the American flag, the white, sleek yacht and the “gringos” made their nicotine-starved minds work out possibilities of buying, swapping or receiving as gifts cigarettes by the carton. They were deeply disappointed on learning that Captain Blanc, Miguel and I did not smoke at all, and that Erling had taken along his very last carton, which he had hidden well to keep it out of reach of my kid brother, who had now started to smoke regularly at Erling's expense, mostly to annoy the piratical looking Norwegian.

As I was in a hurry to get the rum and return ashore, there was no time for hospitality, and the navy boys received no other satisfaction than that of looking over the schooner. Getting ashore however was not as easy as usual, as the breeze had turn quite stiff and made rowing slow. But I was lucky that the old truck was still at the dock and I could get transportation to the port captain's quarters. Walking on Baltra seems strangely difficult, as the long sinuous asphalt roads seem to extent into infinity. They definitely discourage one from using one's feet for transportation. It could be that the wind, the desolate landscape and the monotony of the land are discouraging to one's mind.

Finally, the rum and I made it to the port captain's office, where I found him sitting at his desk, making a not too successful effort at conversing with our skipper. The two of them looked quite stupid as they most of the time did not understand each other. They both wore apologetic grins on their faces and their eyes looked blank. Miguel, who at that time could not speak English, sat comfortably enjoying their more or less vain efforts at communicating.

Then, Captain Blanc and I explained that it was our skipper's birthday and that he would be honored to be allowed to have a few drinks with the port captain. We also hoped that he would pardon us for taking the liberty to bring the bottle of rum to his office. The commanding officer of the base thanked us warmly, took possession of the bottle, and ordered one of his men to bring ice, a luxury unknown in the Galápagos of that time.

While we waited for the ice and glasses, I noticed that the port captain was much more relaxed, and had become less formal. It seems as if he felt more at home with our skipper and me after our display of courtesy and our desire to celebrate the former's birthday with him. However, this was nothing compared to what his attitude became later, as the evening wore on - it had now become dark.

The first drink had still some traces of formality about it, and was mainly a toast to our skipper's bithday. But after this things became smoother, conversation going at a constant flow. For Miguel all this must have been extremely boring. An absolute teetotaler, he sat there sipping iced water from his glass and not getting a word in edgewise, while he grinned more and more vanly as the hours passed. Finally, his grin and expression were such, that he looked completely drunk, while we others did all the drinking. By that time I must have been somewhat tipsy for I caught myself wondering whether I would have to help Miguel get aboard.

Upon learning of Blanc's French origin and after getting better acquainted with me, the port captain got decidedly friendly, going to the extent of placing the whole island at our disposition. I was careful not to ask if the two ladies and the dogs were included in this generous offer. About halfway down the bottle, he showed us some photographs of his daughters, three very good-looking young ladies. I hastened to comment on their handsomeness, while regretting that we were not honored by their presence on the island. My remarks seemed to be well received, as they were sincere.

Around midnight, we departed the good officer's presence, and were driven down to the dock by the chief petty officer. Personally, I was very tired and had a great desire to reach the safety of my bunk. I have never talked more in my life. I had had to repeat in Spanish all that Captain Blanc said, then repeat in English all that our host said. Besides, I also had to stand for my own part of the conversation, which I had to repeat in English and Spanish. One good thing about it all is that I slept very well that night.

Next morning, the truck honked from the dock, calling us ashore. We had just had breakfast, and I was wondering if we would be late in getting ashore. Our skipper had forgotten that we were supposed to be on the dock at eight o'clock for a ride all over the island with the port captain and his chief petty officer, who wanted to show us their domains.

We hurriedly scrambled into the skiff and rowed towards the dock, where we were very cordially greeted by our two navy friends. I shall not go into details about our ride over the deserted roads of the island, as there is nothing much left to be said about this desolate place. But there was one surprising fact that the petty officer told us about. He had seen and shot a goat on one of the roads. Therefore, he now made certain that he had a loaded gun with him whenever he was out driving, in case he should happen to meet any of the few remaining goats - if there were any left.

He also told us of occasionally catching turtles on the beaches during the now almost ended warm season, at the beginning of which these animals come ashore to lay their eggs.Spiny lobsters were also to be caught along the western and southern shores of the island. Unfotunately he had no boat so he could not go out to fish.

Sunday morning, Captain Blanc and I were set ashore on the beach at the head of the bay, and went exploring. Here, we deiscovered two huge installations for distilling sea water. This was a surprise, for I had only known that fresh water was carried over in barges from San Cristóbal, where the Americans had installed a six-inch pipeline from the highlands down to the pier in Wreck Bay.

Two of the boys went in the meantime to look for firewood. Upon returning, we met again our two navy friends, who showed us a boat that the petty officer had beached and was repairing. He complained about having trouble to get out an engine for his little craft. He told us that he planned on continuing in the navy and hoped he would be allowed to remain for some time in the islands. He expected to get a suitable partner to operate his boat and see to it that his crew fished. He could of course not do so himself, as he was bound to remain on shore as long as he continued in the navy.

Later in the day, we had our two friends out for tea, cake and our very last rum. Erling and I acted as cooks and waited on our guests. I noticed that Erling looked constantly at the port captain, who in turn gave Erling some uneasy glances. Evidently, Erling had intended to look at the port captain without being noticed. This only made the object of his scrutiny even more suspicious, for all he did was to give the navy officer some sidelong scowls. This, with his unshaven face and piratical appearance, in addition to his cold blue eyes and disreputable appearance, probably made Lieutenant Crespo consider some horrid possibilities. The ill-tempered frown my brother was wearing at the time did not help.

Maybe the crew of the yacht consisted of murderous escaped covicts or dangerous smugglers. Perhaps the suave skipper and his polite mate were the worst of the lot - in any case, the latter had a suspicious bulge in one of his pockets. There was also a large revolver with a heavy holster and a gun belt that my brother had carelessly thrown over a seat. Even at that time, at the age of sixteen, he had got into the habit of carrying the weapon everywhere he went.

Finally, Erling asked the port captain his name, and informed him that he knew a gentleman in Panama who had exactly the same name and looked very much like him. It was then found out that Erling had been a friend of the port captain's father, who lived in some remote village in Panama, in the Chiriquí mountains. This information made the port captain relax and start enjoying himself.

The next morning was nice and fresh, but the sea was completely calm, without ripples. It promised to become a warm day unless a breeze started up. Since there was no wind, we headed out over the deep blue sea with the help of our engine. We felt no hopes of sailing as we headed for Baquedano Bay (called Turtle Cove by the Americans on the base), on the northern coast of Santa Cruz. There were no sounds other than the purring of the old 150 h.p. Chrysler and the faint splashing of the water against our bow as we parted it. The numerous sea birds were too far from us to be heard.

Mountains in the background are the north side of Santa Cruz seen from Baltra.

I sat by the wheel, taking it all in and enjoying the peace, feeling fine and relaxed. The calm and beauty of the morning had taken hold of me. Even the purple and distant mountains of Santa Cruz that rose against the slightly hazy blue of the sky irradiated total peace. A little ways from our bows, I discovered a group of floating petrels who also seemed to be enjoying the peace of that glorious morning. They did not move away until we were almost on top of them. Then, they settled not far from our port side, scarcely paying any attention to our ship.

While we were approaching our destination, the sky started gradually to become overcast. After an hour and a half of travel, when we anchored off the narrow entrance to Turtle Lagoon, at the head of the bay, the cloud cover hid the whole sky. I had been at anchor here before and we would come back to Baquedano Bay with the Chance, but I never got ashore here, though this was a place I would have liked to explore. From the highlands in the interior one could see a large patch of green vegetation inland from this bay, too far inland to be mangroves. This, and the persistent rumor that fresh water existed in the area, made it most interesting, especially in Galápagos, where fresh water is found in only few places.

The only island with an abundance of fresh water is San Cristóbal, where several perennial brooks are found inland, two of them even running all the way down to the south side of the island, where they form a small waterfall at Freshwater Bay, an open roadstead. Floreana has several springs inland, but only one of them is truly perennial, as the others dry out in periods when there is little rain. On Santa Cruz and Isabela, one depends mainly on brackish water and rain collected in tanks.Thus for the inhabited islands. On uninhabited Santiago there are several springs, none of them reliable.

Everybody left in the skiff, and I remained aboard as I had anchor watch. While walking around the deck, I noticed that a breeze was beginning to blow. It was not quite as strong as that which we had experienced at Aeolian Cove. Little by little, the sun began to look through the cloud cover and I felt its sting on my sore nose that had been peeling during recent days. Meanwhile, I watched how my companions landed and scattered along the shore in search of spiny lobsters.

Along the shore were some mangroves here and there and the occasional shell sand beach. To the south there was a low rocky cliff with a hill standing some distance inland from it. To the north-northeast I could see the entrance to Itabaca Channel, the narrow stretch of water that separated Baltra from Santa Cruz. I noticed that the wind was becoming stronger and coming in with irregular strength. Then, the anchor dragged a little, which made me nervous, especially since my companions were now out of sight. They had entered the narrow, mangrove-fringed channel that leads into the Turtle Lagoon, with its maze of mangrove covered islets and channels

The schooner dragged her anchor some more, enough to make it noticeable when I checked her position against the shore. It was useless to blow the horn we carried, as my companions would not be able to hear me where they now were.

However, storms do not happen in Galápagos. The islands are within the equatorial calms, and really bad weather is extremely rare. I went below for a banana, coming up on deck while eating the fruit. Then, I saw the skiff coming out from the lagoon and heading in my direction. I was relieved to see them, but disappointed when they came closer and I saw that they had not found any turtles. They had only seen sharks in the lagoon. We were in need of oil, as our shortening was getting low, and meat, as we had been living mainly on a vegetarian diet.

We sailed towards the entrance to the Itabaca Channel, anchoring in a little cove before reaching the channel. Here, we went ashore to collect firewood. We found some very good heartwood that was compact as anthracite and so heavy it cannot float even in salt water. It comes from the matasarno tree (Piscidia carthagenensis), also found on the mainland, but in Galápagos only reported from Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal. This heartwood is very popular for posts and was used as framework and support for the old plantation pier in Wreck Bay, on San Cristóbal, where these posts survived year after year without being damaged by shipworms or other organisms.

There were lots of opuntia cacti scattered over the landscape, and Erling stepped on a wobly rock, falling against a young specimen, with the result that he had spines all over his chest and inside his arms, as he embraced the cactus when he fell against it. We spent some time helping him pick out spines, and he finished with most of the rest after getting back on the schooner. For some days he was bothered by the smaller spines that remained.

We slept at this anchorage that night, and could see the fire of a dead cactus that Erling had used his lighter on while we explored the area. Since it was a rather large arborescent cactus, it burnt most of the night. Early next morning, we headed back to Baltra and were received by our navy friends there. We were asked if we could take Petty Officer Erazo and a generator to Black Beach, on Floreana. Since our skipper was interested in seeing much of the islands, he agreed readily, and we set sail at one in the night.

Floreana

Black Beach, the anchorage on the west side of Floreana, with the highest volcano, Cerro de la Paja, in the background. In the middle, the school, and to the right the port captain's office and dwelling.

I had been to Floreana a number of times in the past, mostly fishing out of Las Cuevas, an anchorage on the NE side of the island, far from the inhabited part. I always found Floreana to lack the charm that I found on the other islands. Its characteristic skyline of conical volcanoes gave its landscape a brooding appeareance where it rose out of the sea. It is possible that I was also affected by the island's bloody history and the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Baroness von Wagner and her lover Robert Philipson, the death of her partner Rudolf Lorenz and the Norwegian Nuggerud on Marchena, after they had left Floreana, and the final death of Dr. Ritter, all in the same year of 1934.

Floreana had also been the site of the first organized attempt at colonizing Galápagos, made by General José Villamil, in 1832. It had served soon after as a penal settlement with all its problems.

We arrived to Black Beach in the afternoon, and got the generator unloaded. Erazo went ashore with it to help getting it installed and working, while we headed inland to the oasis above the anchorage, a relatively short hike inland. Here, is a water hole and there were then still a number of coconut plams and some date palms growing there. These had all been planted by a German, Dr. Friedrich Ritter, who had arrived to the island in 1929. We visited Ritter's grave, where he had been buried in 1934, after dying of food poisoning.

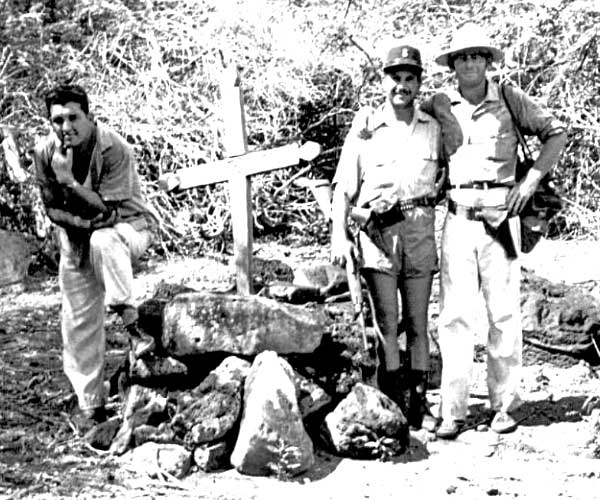

The grave of Dr. Friedrich Ritter, in the oasis above Black Beach. From left, Dr. José Ochoa of the Ecuadorian Navy, Lt. Humberto León (chief of police in Galápagos) and the author.

The following morning, we went inland again, this time to visit the Wittmer family, who had been living on the island since 1932. I knew them well, as I had visited them before, and my mother and I had shared a cabin with Mrs. Wittmer, when they first came to the islands. My mother and I left the ship on San Cristóbal, where my father awaited us in his sloop rigged vessel, while the Wittmers continued on to Floreana, to start their lives there.

The Wittmers received us with their usual hospitality. We were served Wittmer's home made schnaps and coffee with delicious cookies. We were shown photographs and the guest books, of which there were several. Captain Blanc was moved to find the Chance entered in one of them. We were also shown around their well kept farm and given some fresh eggs. On the way back to the beach, we stopped again at the oasis and found the Cruz brothers there—Eduardo and Eliezer—who had been living on the island since the 1940s and had their families with them. We sailed again at 3 o'clock in the morning, heading for Baltra, where the skipper and I were invited for supper at Lieutenant Crespo's quarters at the base.

Santiago

View of Sulivan Bay, off the southeast coast of Santiago, seen from Bartholomew Island.

Two days later, we sailed early in the morning for Santiago, arriving to Sulivan Bay, on the SE side of that island. Santiago, officially known as San Salvador, is a rather large island, uninhabited and located at the center of the archipelago. It has a moist region in its higher parts, so it is potentially inhabitable, but as far as we know no attempt at colonizing it has ever been made. At the time of our visit, much of the interior was still little known.

Sulivan Bay is a rather desolate place, with extensive jagged lava fields out of which rise conical tufaceous hills that are obviously much older than the surrounding lava. There is little vegetation, except for the greenery here and there along the shores, consisting mostly of white mangrove with a few other halophytic plants. The most used camping site of the island fishermen is Bartholomew Island, a small rugged island that forms the south shore of this bay. However, we anchored farther north, next to a steeply rising coast of bare lava. We did not remain long, continuing our sailing outside this forbidding landscape, past Buccaneer Cove, on the NW side of the island.

Buccaneer Cove seems to have been a favorite with the tortoise hunters in the 19th Century, as the access to the interior of the island is shorter and easier from this anchorage than elsewhere along the coast. We did not enter the cove, sailing past it, then between Albany Island and the larger island, into James Bay, on the west side of Santiago. This bay was a favorite with the buccaneers towards the end of the 17th Century.

Here, the landscape changes dramatically. The bay is divided by an extensive and bare lava field that fans out from the interior and ends in low cliffs by the sea. North of this field, the terrain is rugged and rises steeply towards the interior and the highest mountains of the island. The whole area north of the lava is well wooded. This northern part is limited to the NW by Cape Cowan, an abrupt headland on top of which there are several springs. This cape is named after Lt. John S. Cowan, who was killed in a duel on the large beach south of the cape, while the U.S. Frigate Essex was anchored here, in 1813.

View of James Bay, looking towards the lava field that divides the bay.

Above the beach is a wide swath of green vegetation, consisting mainly of white mangroves. Behind it were then still two shallow lakes of briny water, frequented by flamingos that also nested here. These lakes were filled with mud during the unusually heavy rains of the 1982-83 warm season, and no longer exist. We did not land here, but continued to the south of the bay, where the landscape is very different.

South of the lava field, the coast consists of tufaceous cliffs separated by the beds of several intermittent brooks that run into the bay in rainy periods and form small beaches. We headed for the southernmost of these, where landing is easier than elsewhere. The landscape is open, with trees growing scattered all over, with low vegetation such as grasses and small shrubs between them. It all gives the place the appearance of an African parkland. The ground consists of layers of tuff, which look like pale colored brick. Towards the south rises the conical Sugar Loaf Mountain, an extinct tuff volcano.

The trees we found on landing were mostly palosanto (Bursera graveolens) with their spreading, flexible branches of a silvery gray color still in leaf. The tender green of the leaves gave them a beautiful appearance. There were also a few scattered acacias still with their delicately scented yellow flowers. At one place we came across a fenced in area shaded by a large acacia. The fence was built of pieces of tuff that had been piled on top of one another. We knew that this was all that remained of the home of Frances and Ainslie Conway, an American couple who had lived here twice—once shortly before the war and afterwards when the war had ended. At the latter time they had had to leave because of Ainslie's health. The couple wrote two books about their experiences in the islands.

Blanc wanted to see the spring on the side of Sugar Loaf Mountain, so we headed in that direction. He carried a rifle with him in the hope of killing a goat, and we did find a herd resting under some trees. The skipper shot and one of the animals, a young female, jumped into the air and started running, while the whole herd spread, fleeing inland. Believing the young female to be wounded, and feeling sorry for it, I ran after it on a mad scramble across the open terrain. Finally, after considerable effort, I cornered the animal behind a high bush, at the foot of a steep tuff wall that formed one side of a dry water course.

The animal could flee in each of two directions on the sides of the bush, so I jumped on top of the plant and grabbed its horns. With my right hand, I took out my hunting knife and slit the animal's throat. It died very quickly. Erling, who had been following me and shouting encouragement all the while, helped me carry the beast down to the beach, where we placed it on a flat stone and gutted it.

In the meantime, Blanc had gone inland a ways and met with some donkeys. Not knowing that we had succeeded in getting the goat, he shot one and left it there to be picked up later. Farther inland, he met with a young pig, which he also shot. Thus, we had plenty of meat for a change, and I spent the afternoon salting meat, as we had no refrigeration. Still, we had time to visit the spring, which was nearly dry at that time, a tiny stream running down from a rocky wall that seemed to sweat drops of clear water. Several depressions had been cut in the tufaceous water course to help collect the water, but these were filled with gravel. The water disappeared into the loose soil a short distance downhill.

Next morning, we visited the salt crater. This is a low hill close to the lava field which has a shallow lake inside its crater. The inside is very steep, and covered with a scattering of palosanto trees. The lake consists of concentrated brine and the salt forms by evaporation, sinking layer upon layer to the bottom. These layers become hard and are separated by thin layers of mud from the soil that washes down to the lake from the sides of the crater during rainy periods. The salt is of a high quality, containing 98% of sodium chloride.

Isabela

Crater of the Santo Tomás Volcano, on the southeast side of Isabela. It is the largest crater in the islands, with a diameter of nine and a half kilometers.

After our short stay in James Bay, we set sail for the north of Isabela, the largest of the Galápagos Islands, which consists of five huge volcanoes whose bases have been joined by lava flows. The island consists largely of desolate lava fields and has in most parts a forbidding appearance. However, there is a settlement on the SE side, Puerto Villamil, and there are farms on the south side of the 1440 meter high Santo Tomás Volcano. This latter has a huge crater, all of nine and a half kilometers in diameter.

We sailed past steep Redondo Rock, off the north shore of Isabela, anchoring at Point Albemarle. The country here was mostly bare lava, all the way up to the lofty mountain (1700 meters) that rises inland. There was some greenery along the shore, but it consisted of mangroves and other salt loving plants. Otherwise, the lava fields had some cacti scattered here and there—opuntiae and cerei. We saw a number of sea birds, mainly pelicans and boobies, and a green heron. We also saw mullets and other fish and managed to catch a few spiny lobsters along the shore. One day, we caught a turtle, which I butchered the same day. It gave us some oil and fresh meat for a couple of days.

There was still a tower standing that had belonged to a radar station, as well as the remains of concrete floors on which the wooden building of this small base had stood during the war. There was also a stranded tuna clipper, the Glory of the Seas, which had come too close to the shore and been grounded a year or so earlier.

We saw a lot of cormorants. The Galápagos cormorant is too large and heavy for its atrophied wings and is unable to fly, but it swims at an impressive speed under the water. This bird has its habitat in the western parts of the islands. There were also some enormous manta rays in this area, and I had a shock when I discovered one that was seven feet, from wing tip to wing tip, swimming silently under the skiff while I was rowing out to the schooner. I know these animals are supposedly harmless to humans, but its dark upper part had a sinister appearance, and we had heard and seen how they jump into the air, falling back on the water with a sound that was like a canon shot.

Fernandina

The northeast coast of Fernandina, the westernmost of the Galápagos Islands.

We sailed to the west from Point Albemarle, then turned south to enter Canal Bolívar, after passing the enormous Banks Bay, which we did not enter. The landscape here is very barren, consisting of extensive lava fields. The mountains inland are high and steep. On the other side of Canal Bolíver, we could see the main mountain of Fernandina, a large and forbidding island which, like Isabela, has several very active craters.

We anchored at Punta Espinoza, the NE corner of Fernandina, where we landed on the rocky shore, meeting with numerous penguins, cormorants, boobies and pelicans scattered along the shore. Inland were some shallow salt water ponds, surrounded by mangroves. There were also mangroves along the shore itself, but otherwise there was very little plant life in the area. Erling tried to make friends with a penguin, which looked rather tame. However, the bird attacked him when he came too close, making us all laugh at his expression of hurt surprise.

Captain Blanc said that he would wait a day for anyone who wanted to climb the island, which we all felt like exploring, but seeing the rugged lava that went up all the way to the top of the main mountain, we who were used to the island terrain realized that a trip to the rim of the main crater would need at least twice as much time and better preparation.

We knew there was a lake in the main crater, which had been discovered by the Americans while flying over the island, but at the time we were there nobody had as yet visited this lake. Some years later, an American attempted to settle by this lake, but reaching it he found that it had disappeared. With all the volcanic activity on this island, the lake reappeared later, with its bed removed to one side of the main crater.

Next morning, we sailed across to Tagus Cove, on the Isabela side. This cove is a narrow formation between tufaceous cliffs, and gives good shelter. It is possible to land at its head, where an intermittent stream has cut a bed through the soft rock. The place is desolate, but with more vegetation than the lands to the north, between Tagus Cove and Banks Bay. There were scattered palosanto trees, a few mimosas, and dried sedges and grass. There were also signs of civilization in inscriptions worked into the tuff cliffs with the names of visiting ships. I recall one with the name Phoenix and the year 1836, that was fading from erosion. There was also an old acquaintance, the Falcon with the date 1935. The Falcon was a vessel from Santa Cruz on which I had made fishing trips in 1947 and 1948.

At the head of the cove was a wooden box, covered in painted canvas and intended for leaving letters to be picked up by visiting ships. I have been unable to find any records of this box, and it was gone when I visited the cove a few years later. This may have been an attempt to imitate the post barrel at Post Office Bay, on the north coast of Floreana, which was first established at the time of the whalers.

We left that same afternoon, heading south, and passing Elizabeth Bay, a large bay that forms the western shore of the Perry Isthmus, and has extensive mangrove swamps. We had some shifting wind conditions and alternately sailed and drifted, thus reaching Iguana Cove, the SW corner of Isabela, above which rises the second highest volcano in the islands, Cerro Azul. I would get to know that area rather well in 1959, when I made several visits to Iguana Cove. Here, the moist region stretches all the way down to the seashore at Iguana Cove and Point Essex, there being more rains farther down than elsewhere in the islands, due to the height and steepness of the mountain.

After coming clear of Isabela, we did some tacking, but drifted much of the night. We had to keep a keen watch, for the current sets against the land, and the land is exposed and rocky. By daybreak we had reached Tortuga, a small island outside Puerto Villamil, where the ships visiting the island anchor up. There was also a penal colony on the island at the time, so Captain Blanc was not interested in visiting the place.

We sailed past the rather high Crossman Islands, a group of steep islets outside the SE coast of Isabela, then reached the channel that separates Isabela from Santa Cruz. From here, since it was a clear day, we could see Floreana, Santa Cruz, Duncan and Santiago, as well as Isabela. We set our course towards the NW coast of Santa Cruz, in order to visit Conway Bay, but stopped first at Whale Bay, a small cove south of it. Here, there is a steep hill with a long, narrow summit.

Landing on the small beach at the foot of the hill, I found that the sand here was quite different from that on other Galápagos beach, which cosnsist mostly of shell sand. The sand here was made up mostly of tiny green chrysolite crystals. It was at this place that the first known inhabitants of this large island lived in the 1840s, probably tortoise hunters. At the time there was a trail going inland and up into the mountains, where there is a fresh water spring at Santa Rosa. There had also been two small farms there, that are said to have been set up by orders from don Manuel Julián Cobos, owner of the sugar plantation on San Cristóbal, who used these plantings to provide food for his workers when they hunted tortoises and gathered archil in the area.

Captain Blanc and I climbed the steep hill. After going down, we rowed out to the schooner, and started sailing north. There was a stiff breeze blowing from the SE so we made good time past the high islet of Eden, north of which we found shelter and good anchorage. However, rowing ashore was hard work on account of the wind.

I had visited Conway Bay several times before with the Falcon and camped there. I recalled the nights sleeping ashore with the mosquitoes and a special night when we had heavy rains and I had to get up and wring out my blanket several times. We landed on one of the shell sand beaches in a typical Santa Cruz landscape with black jagged rocks, palosanto trees (which had unusually thick trunks here), thorny shrubs, cerei and opuntia cacti. Wherever there was soil, grew a coarse grass. Along the shore we saw mangroves, and other salt loving growths. There was also an abundance of animals such as mocking birds, finches, lizards and land iguanas. The holes dug by the iguanas were numerous in those places where some soil was found.

There were numerous donkey trails in the area inland from the bay, and we found cat scats and signs of goats. After our little expedition inland, we were very thirsty and found a bath in the sea quite refreshing. Then, we rowed out to the schooner. While we rowed, the wind changed suddenly, coming in from the north, then died. Thus, we had to motor back to Baltra, our next stop. On our way, we anchored for a while at Puerto Baquedano to attempt catching turtles. Here, we found a British yawl, and invited the two men for a visit to the schooner.

Not succeeding with the turtles, we had caught some spiny lobsters along the shore, making good use of the low tide. In the early afternoon, we set course for Baltra, anchoring up in the cove. When entering Aeolian Cove, we found the Calderón, a naval transport ship, tied to the dock. Everybody aboard came to its starboard side to watch us tie up to a buoy that was anchored a little distance in from the dock.

We were much admired, as we maneuvered flawlessly. Blanc stood forward, signaling me with his arms, as I steered in, with the engine running very slowly. My borther and Erling were in the skiff, with the end of the anchor chain, while Miguel was on deck, letting out more chain as needed. At the moment the skiff reached the buoy, I stopped the engine and reversed slightly to stop the schooner, the boys in the skiff put the chain through a ring on the buoy and shackled it. Everything went so perfectly, that we were praised by some of the naval officers.

On the Calderón came Arne, Erling's elder brother, who had been living in Guayaquil. He was very interested in the schooner, but would not come with us, as we were not going to Santa Cruz at once, while the navy ship was leaving for Academy Bay that night. We were going to beach the schooner on the large sand beach at the head of the cove to make some repairs on her stern, which had a leak.

Next morning, we headed for the beach bright and early. Just outside it, we turned around and went stern first towards the beach, until we hit bottom. We had already set an anchor from the bow. Now, ropes were paid out to be tied onto trees above the beach. The waves that rolled against the beach were fortunately not big enough to give us problems.

After the tide went out enough for us to work on the stern, we released two of the copper plates in the leaking area and lifted off the tarred felt that was below them. We found a seam that need recaulking, and fixed it. Then replaced the felt and the copper plating. When the tide was in again, we freed the schooner from the trees and pulled in the anchor, thus coming clear of the beach and being able to engage the engine, which was already running.

Early in the morning we started out for Academy Bay, on the south side of Santa Cruz, arriving home that afternoon. We had been away for about a month when we got there.

Academy Bay, on the south side of Santa Cruz. Photo taken in the 1960s, when there still were few changes in the appearance of the settlement.