UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC

AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION REPORT ON A

BIOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE OF THE

GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS DURING 1957

Robert I. Bowman

(1925-2006)

December, 1917: This document is available for download at SCRIBD. Additional editing done to conform to HTML 5 requirements. Hover over any text to display Chapter number and title.

In July 1957, Ecuador issued a series of six stamps featuring the Galápagos Islands, usable only on the islands. Revenue from the sale of these stamps is to be used exclusively for public works projects on the islands.

Chapter 1: Introduction

The “Archipiélago de Colón,” more commonly known as the Galápagos Islands, is situated approximately 500 miles west of the mainland of Ecuador to which country it belongs. The group is composed of five large and seven small islands, numerous islets and reefs, distributed about the equator at the same longitude as the city of New Orleans.

Historical importance of the Galápagos Islands

Tales of unusual biological productions and of human strife in the Galápagos region have long attracted the attention of historians, story writers, and scientists. During the seventeenth century the islands served as a hideout for pirates of the Eastern Pacific trade routes, on whose shores fresh meat in the form of titanic tortoises and docile doves could be readily obtained. Near the close of the eighteenth century freebooting gave way to whaling, and with the beginning of hostilities between Great Britain and America, gunboats executed many sea raids around Galápagos designed to harass English shipping (von Hagen, 1940). In 1841 the novelist Herman Melville visited the Galápagos Islands aboard a whaling ship and they became the locale of his charming essay The Encantadas.

Scientific interest in the islands begins with the writings of Charles Darwin and particularly his On the Origin of Species which was first published in 1859. When Darwin visited Galápagos in 1835 as naturalist aboard the world-cruising H.M.S. Beagle, he was so impressed with what he observed that he wrote as follows in his diary of 1837:

“In July opened first notebook on ‘Transmutation of Species.’—Had been greatly struck from about month of previous March on character of S. American fossils—species on Galápagos Archipelago.—These facts origin (especially latter) of all my views.” (Barlow, 1933: xiii)

The Galápagos Islands present a unique assortment of plants and animals which make them especially attractive to biologists. For example, there is a group of finches composed of 13 species, each of which in some degree resembles the other species, especially in manner of song, plumage, nest, and so forth, but differs from the others most conspicuously in size and shape of bill. However, one of the unusual features is the frequent occurrence of individuals showing such an inter-mediation of characters that they defy specific allocation. To the evolution-minded Darwin these birds, it was reasoned, could have been the descendants of a common ancestor with bills now adapted to “different ends.”

Two kinds of iguanas living on the Galápagos Islands may have provided Darwin with additional “food for thought” on the origin of new species. The brilliantly coloured land iguanas are distributed on many of the islands, often living but a few yards from their nearest relative, the no-less-colourful marine iguana—the only lizard in the world which enters the ocean to forage.

Most impressive to the eyes of buccaneers and whalers of past centuries, as well as modern visitors to the islands, are the gigantic land tortoises, some of which attain a weight of over 500 pounds. These reptilian monsters occur naturally in no other place in the world, save for a few islands in the Indian Ocean where a similar species still survives.

A distinct species of penguin lives inconspicuously amongst the western islands directly under the equator—the sole members of a typically Antarctic or south temperate group of flightless birds occurring in “tropical” waters. Another non-volant bird, the flightless cormorant, lives close by the penguin foraging for fish in the cool nutrient-rich waters of the Humboldt (Peru) Current. This northwesterly drifting oceanic stream is largely responsible for the anomalies in the would-be “tropical” climate, causing widespread aridity along the low cactus-studded coasts and frequent heavy rainfall in the humid forests of the highlands. Giant tree-like cacti and 60 feet tall sunflower trees are but two more examples of the many unusual biological productions for which Galápagos is famous.

Few places in the world offer such a glorious panorama of “moon-like” landscape, or present such an array of volcanoes (some of which are erupting this very day) as may be found on Galápagos. The inhospitable nature of the coastal regions, whose sun-parched lava supports but a growth of spiny plants, is largely responsible for the retarded human colonization of these islands. Within the past century and a half there has been extensive penetration of the moist highlands of the larger islands and the development of plantations, so that these “Enchanted Isles” are now capable of supporting a limited human population.

In the past few years there has been a revival of interest in Galápagos by the government of Ecuador, which is directed mainly at agricultural expansion through increased colonization, and toward the development of tourist attractions. As a result, new demands have come from internationally-minded conservationists that appropriate action be taken to safeguard the Galápagos biota from further destruction.

Coupled with this upsurge of human activity in Galápagos are the dangers presented by predatory feral cats, dogs, and pigs, which find easy prey in the tame birds, lizards, and tortoises.

Recent interest in the conservation of the Galápagos biota

Fearing the possible extinction of the Galápagos tortoise by the oil hunters, in 1928 the New York Zoological Society sent Dr. Charles H. Townsend to Galápagos to procure a breeding stock of the animals for colonization in the southern states of the United States. He brought back 180 individuals from Albemarle Island. Some of the tortoises collected in 1928 are still alive in zoos today.

In 1930, Dr. Townsend reports (1930: 153) that an attaché of the Consulate of Ecuador in New York requested his opinion as to what steps should be taken by the Ecuadorian government for the preservation of the animal life of the Galápagos Islands. This gentleman also made inquiry as to whether a scientific association, such as the New York Zoological Society, would be interested in undertaking the supervision of some method of conservation that might be found desirable.

In 1936 formal action was taken to enforce the 1934 statutes which provided for the protection of the Galápagos fauna and flora. On 14 May of that year a decree was signed by Ecuador's Provisional President Paez, by which the following islands were declared to be national parks and reservations for the flora and fauna: Hood, James, Barrington, Jervis, Seymour, Daphne, Tower, Bindloe, Abingdon, Culpepper, Indefatigable, and that part of Albemarle between Albemarle Point and Perry Isthmus. It was further stated that a board of directors should supervise the protection of plant and animal life on the islands and the establishment of research stations (Atwood, 1940: 49). It is uncertain whether the provisional committee of Dr. Teodoro Maldonado Carbo, Dr. Antonio Parra V., and Messrs. Francisco Campo K., Eduardo Mena, and Jonas Guerro, named in the decree, ever functioned as intended.

One of the most active American scientists Interested in obtaining better protection of the Galápagos biota during the latter part of the 1930's was Dr. John S. Garth of the Allan Hancock Foundation, University of Southern California. Dr. Garth accompanied the Foundation’s research vessel [Velero III] to Galápagos on its numerous expeditions (see Meredith, 1939). § In 1937 he called upon Dr. John C. Phillips, then Chairman of the Executive Committee of the American Committee on International Wildlife Protection to see what might be done through that organisation to promote more effective conservation of the Galápagos biota. Cooperating with Dr. Garth was Dr. Waldo L. Schmitt of the United States National Museum who with Dr. Garth always maintained that a permanent station on the Galápagos Islands was the only way to study and protect its fauna and flora. Unfortunately, nothing tangible resulted from these efforts.

§ See also C. McLean Fraser's Table of scientists …

In 1946 efforts were renewed to bring the Galápagos Islands under more favourable wildlife management, and at a meeting of the Pacific Science Conference of the National Research Council, held in Washington, D.C, 6-8 June, the following recommendation was presented:

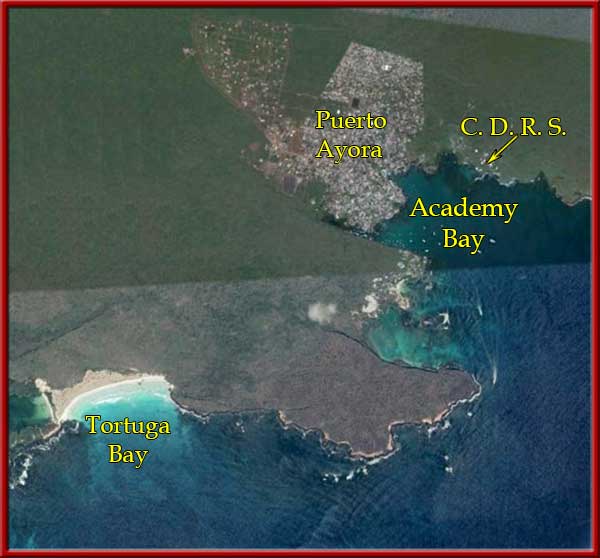

“That steps be taken toward the establishment of a base research station for various types of scientific investigation in the Galápagos Islands, making use of existing installations. The base should be of a permanent nature because of the importance of maintaining continuous oceanographic, biological, and meteorological records from this island outpost of South America. By way of specific illustrations of projects for this station, it may be pointed out that various elements of the land fauna are little known; that the extraordinary humid zone of the south face of the larger islands offer the opportunity for a unique ecological mountain transect, especially from Academy Bay and Indefatigable Island; that the more barren coasts and islands afford simplified ecological conditions, comparable to those of Arctic islands, and provide a veritable field laboratory in themselves; and that the biological interest of these islands is so great that conservation measures, under the control of such a research station, are urgently required.” (Bull. Nat. Res. Council, No. 114, Sept. 1946, p. 43.)

Active in promoting this and other recommendations were Dr. Harold J. Coolidge, Executive Secretary, Pacific Science Board, and Vice-chairman of the Continuation Committee designated to implement this and other recommendations of the conference, and also Dr. Dillon S. Ripley of Yale University.

“UNESCO, under the guidance of its first Director, Dr. Julian Huxley, had on several occasions shown its anxiety that at least certain parts of these islands might be allowed to become effectively protected and maintained intact.” (Press Release of the I.U.C.N., Sept. 1956)

In the Fall of 1955, Dr. Robert I. Bowman and Dr. I. Eibl-Eibesfeldt wrote independently to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and presented their first-hand observations on Galápagos, pointing to the need for more effective conservation practices and the desirability of establishing a permanent research installation on the islands.

In January 1956, Dr. Bowman sent copies of an article to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as further evidence of the immanency of the dangers to the Galápagos biota. Subsequently, public interest in this cause was effectively aroused through letters from numerous other scientists in America and Europe addressed to I.U.C.N. President, Prof. Roger Heim, and its Assistant Secretary-General, Mme. Marguerite Caram.

Mr. Jean Delacour, President, and Dr. Dillon Ripley, Secretary, of the Pan-American Section of the International Committee for Bird Preservation, met with Ecuadorian officials in Quito during May 1956 in an attempt to interest them in the creation of a biological field station and national parks on the Galápagos Islands. (See Bull, of the I.C.B.P. for 11 July 1956, p. 2)

These activities were culminated in the following resolution passed at the Fifth General Assembly of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, held in Edinburgh, 20-28 June 1956:

“The Fifth General Assembly, having taken note with approval of the interesting report submitted by the Survival Service Committee, is deeply concerned by reports which have been received by the Union regarding the precarious situation of various species of fauna and flora endemic to the Galápagos Islands which are entitled to protection under the Ecuadorian laws which were established in 1934. The General Assembly is likewise concerned by reports in the press of plans for the large tourist and economic development of the resources of the Galápagos Islands which might further jeopardize the endangered species found there. They recommend that qualified naturalists should be encouraged to visit the Galápagos Islands to make a survey and ecological studies of the fauna and flora and express their hope that facilities will be provided by the Ecuadorian government or through some form of international technical aid so that a small housing unit or laboratory might serve as a base for such scientific work. It is hoped that additional funds may be found to support a long range scientific programme in the Galápagos Islands and as part of such a programme, certain islands of the Galápagos Archipelago might be set aside as permanent reserves to enable the fauna and flora to remain undisturbed and so as to provide for long term research.”

Dr. Harold J. Coolidge has informed me that the 9th Pacific Science Congress held in Bangkok (1957) passed the following resolutions:

“In view of the endangered status of many elements in the indigenous fauna and flora of the Galápagos Islands, the Congress resolves that:

“The Congress views with satisfaction the institution of efforts by UNESCO and by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources with the support of the Government of the Republic of Ecuador, to establish protection for the fauna and flora of the Galápagos Islands. The Congress especially recommends the establishment, as soon as possible, of a research and observation station in the archipelago, and urges the support of such station by international funds.”

In April, 1957 the I.U.C.N, was successful in obtaining financial assistance from UNESCO to send Dr. Eibl-Eibesfeldt on “a first mission of reconnaissance” to Galápagos. Through the energetic activities of Dr. Dillon Ripley, acting as coordinator of several American organizations also keenly interested in the Galápagos reconnaissance, financial support was obtained for Dr. Bowman in order that be might serve as the American delegate on the UNESCO reconnaissance. The four groups contributing to his expenses were, International Committee for Bird Protection (Pan-American Section), Life Magazine, New York Zoological Society, and the Conservation Foundation.

The main purposes of the survey were as follows:

- To determine the practicality of establishing a permanent scientific station on the Galápagos Islands.

- To locate a possible site for such a station.

- To explore with Ecuadorian officials the possibility of setting aside one or more islands in the Galápagos as an International wildlife reserve.

- To check on the distribution, relative abundance, and ecology of certain “vanishing” species.

- To obtain adequate photographic documentation of the Islands and their biota for publicity purposes.

On 5 July 1957, accompanied by personnel from Life Magazine, namely, Mr. Rudolf Freund, illustrator, and Mr. Alfred Eisenstaedt, photographer, Eibl and Bowman departed by airplane from New York City for Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the philanthropic organizations mentioned above whose grants made it possible for the writer to participate in the Galápagos reconnaissance, there are many individuals who have contributed directly or indirectly to the success of the survey. The following deserve special mention: Prof. Roger Heim and Mme. Marguerite Caram of the I.U.C.N., who in large part are responsible for the successful guidance of the present project from its inception to the commencement of the field work; Dr. I. Eibl-Eibesfeldt, whose enthusiasm and initiative in promoting this project with the I.U.C.N. was instrumental in obtaining the support from UNESCO; Dr. Dillon S. Ripley, Yale University, who has combined his long standing scientific interest in the Galápagos biota with his administrative talents to coordinate American support for this project; Miss Patricia Hunt, Nature Editor of Life Magazine, who cheerfully accepted and skillfully carried out a large share of the work of planning the expedition; Dr. Fairfield Osborn, New York Zoological Society, whose prestige and administrative experience in organizing scientific expeditions have served the Galápagos mission most profitably.

Active cooperation of the government of Ecuador, on whose request the survey mission was sent to the Galápagos Islands, facilitated the field work through the generous contribution of rapid transportation to and among the islands, and the free use of the wireless radio, and in many other ways. The friendly cooperation of official and non-official Ecuadorian citizens wherever we went was most gratifying.

The members of the expedition extend to the following Ecuadorian officials special thanks for their aid and hospitality; Dr. Camilo Ponce Enrique, President of the Republic; Sr. Ingo Alfonso Calderon Moreno, Minister of National Defense; Sr. Carlos Tobar Zaldumbide, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Dr. Jose Baquerizo Maldonado, Minister of Education; Sr. Guillermo Ordonez, Commander General of the Navy; Sr. Rafael Andrade Ochoa, Commander General of Aviation; Sr. Jorge Crespo Toral, Coordinator General for Technical Assistance; Sr. Guillermo Davalos, Capt. of Patrol Boat 04; Sr. Arturo Menu and Sr. Rovere, Port Captains at Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island; Sr. Gomar, Governor of Galápagos, and Sr. Larrea, Acting Governor of Galápagos.

Especially helpful in practical matters on Galápagos were Mr. and Mrs. Miguel Castro, Mrs. Helen Corey, Mr. Karl Angermeyer, Mr. Erling Graffer, Mr. Gilberto Moncayo, Mr. Enrique Fuentes, Mr. Cecil Moncayo, and Mr. Carl Kübler. Mr. Ernest C. Devine put his amateur radio services at our disposal and helped in other ways.

Mr. Anthony E. Balinski, resident representative of the United Nations Technical Assistance Board in Ecuador, served as our official adviser and guide while in Quito and assisted in many other ways; Mr. Christian Ravndal, United States Ambassador, and Sr. Jorge Jurado of El Comercio, aided our group on many occasions; Sr. Ralpho Del Campo of Panagra, was of much service in expediting our official duties while in Guayaquil.

The writer is grateful to Dr. Alden Miller, Director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, for advice, material aid, and loan of scientific equipment. Dr. Carl L. Hubbs, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Dr. R.C. Miller, Dr. Robert T. Orr, and Dr. Earl Herald of the California Academy of Sciences, and Francis and Ainslie Conway, Berkeley, California, offered freely their advice in the planning stages.

I am grateful to the administration of San Francisco State College for releasing me from academic duties during the Fall semester, 1957.

Finally, special acknowledgment should be made of the enthusiastic participation of Mr. Pruand and Mr. Eisenstaedt throughout the course of the survey. Life Magazine should be highly commended for additional contributions which made it possible for the group to extend their activities to important areas which would otherwise have been by-passed.

Chapter 2: Expedition Itinerary

| July | |

|---|---|

| 5 | Leave New York City by airplane. |

| 6 | Arrive in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Freund, Eisenstaedt, and Eibl depart for Quito. Bourns remains in Guayaquil for discussions with Mrs. Helen Coray, domestic manager of our expedition. |

| 7 | Bowman departs for Quito. Reception for mission at home of U.S. Consul, Mr. Jerry Culley. Among officials attending were Mr. Ravndal, U.S. Ambassador; Mr. Balinski, United Nations Technical Assistance Board; Sr. Calderon, Minister of National Defense; Sr. Andrade, Commander General of Aviation, etc. Dinner at home of Sr. Jorge Jurado of El Comercio. |

| 8 | Meeting with the Coordinator of Technical Assistance for Ecuador, Sr. Jorge Crespo. This was a “work” session to present details of the Galápagos mission. Mr. Balinski acted as interpreter. Meeting with American Ambassador to arrange details of passports. Meeting with Minister of National Defense and Commander-Generals of Navy and Aviation to prepare details of transportation to Galápagos via Government airplane and ship. Reception at home of Mr. Jan Schreuder, Director of Arts at UNESCO`s Casa dela Cultura; other guests included Sr. Carlos Mantilla, Editor of El Comercio, which newspaper has given the Galápagos mission much favourable publicity, and other local dignitaries. |

| 9 | Airplane trip over Andes courtesy of the Ecuadorian Government, accompanied by many officials. Audience with the President of the Republic, Dr. Ponce. Meeting with Dr. Acosta-Solis, Director of the Instituto Ecuatoriana de Ciencias Naturales. Meeting with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sr. Tobar. Meeting with the Minister of Education, Dr. Baquerizo to discuss practical measures which the Government of Ecuador might take to further the cause of our mission. Attended meeting of the Comité Nacional del Año Geofísico Internacional and the Subcomisión Técnica de Trabajo de Oceanografía to inform members of the importance of a research station on Galápagos. |

| 10 | Leave Quito for Guayaquil. Meeting with Naval Commander of District No. 1 concerning the shipment of cargo on El Oro to Galápagos. Meeting with Mrs. Helen Coray to prepare list of materials to be purchased for expedition. |

| 11 | Clear baggage through customs. Made purchases of food, etc. end load these on board El Oro. |

| 12-14 | Relaxation in Guayaquil and Playas, awaiting departure of Catalina for Galápagos on 15 July. |

| 15 | Leave Guayaquil by Catalina at 10.45 a.m. Arrive Baltra air strip, 3.45 p.m. Transfer cargo to El Oro which was awaiting our arrival at the air strip. |

| 16 | Sail from Baltra to Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island. |

| 17-19 | Make preparations at Academy Bay. |

| 20-23 | Trip to “Tortoise Country,” Indefatigable Island. |

| 24-26 | Academy Bay |

| 27 | Academy Bay to Duncan Island. |

| 28 | Duncan Island. |

| 29 | Duncan to Jervis Island. |

| 30 | Jervis Island. |

| 31 | Jervis to James Island. |

| August | |

| 1-2 | James Bay, James Island. |

| 3 | James Island to Bartholomew Island. |

| 4 | Bartholomew to Eden Island. |

| 5 | Eden to Conway Bay, Indefatigable Island. |

| 6-12 | Academy Bay. [11 Aug. Eisenstaedt and Freund leave for Baltra Island.] |

| 13 | Academy Bay to Cartago Bay, Albemarle Island. |

| 14 | Cartago Bay to west side Abingdon Island. |

| 15 | Abingdon Island. |

| 16 | Abingdon to Tower Island. |

| 17-18 | Tower Island. |

| 19 | Tower Island to Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island. |

| 20-29 | Academy Bay. [Freund returns to Academy Bay, 23 August and departs for Narborough Island, 2 August sic, September?] |

| 30 | Academy Bay to Barrington Island. |

| 31 | Barrington Island. |

| September | |

| 1 | Barrington Island to Academy Bay. |

| 2 | Academy Bay to Tagus Cove, Albemarle Island. |

| 3-15 | Narborough Island. |

| 16 | Narborough Island to Elizabeth Bay, west side of Albemarle Island. |

| 17 | Elizabeth Bay to Academy Bay. |

| 18 | Academy Bay. |

| 19 | Academy Bay to Charles Island. |

| 20 | Charles Island. |

| 21 | Charles Island to Gardner-near-Hood Island. |

| 22 | Gardner-near-Hood Island. |

| 23-24 | Hood Island. |

| 25 | Hood Island to Academy Bay. |

| 26-27 | Academy Bay. |

| 28-29 | Highlands of Indefatigable Island. |

| 30 | Academy Bay. |

| October | |

| 1-7 | Academy Bay. |

| 8 | Highlands of Indefatigable Island. |

| 9 | Tortuga Bay, Indefatigable Island. |

| 10-11 | Academy Bay. |

| 12 | Tortuga Bay, Indefatigable Island. |

| 13 | Academy Bay. |

| 14 | Academy Bay to Barrington Island. |

| 15 | Barrington Island to Gardner -near -Hood Island. |

| 16 | Hood Island. |

| 17 | Hood to Chatham Island. |

| 18 | Chatham Island. |

| 19 | Chatham to Barrington Island. |

| 20 | Barrington to Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island. |

| 21-30 | Academy Bay. |

| November | |

| 1-21 | Academy Bay. |

| 22 | Academy Bay to Chatham Island. |

| 23-25 | Chatham Island to Guayaquil, Ecuador. |

| 26-27 | Guayaquil, Ecuador. |

| 28-29 | Guayaquil to Miami to San Francisco. |

Discussion with Ecuadorian Officials

During our brief visit to Quito, 7 to 10 July, inclusive, numerous discussions were held with various Ecuadorian officials, all of which, in general, reflected considerable interest in our mission and assured us of full cooperation whenever requested. Expressions of their sincerity and willingness to help are reflected in the following:

- The Minister of National Defense, through the Commander-General of Aviation, placed a Catalina Flying Boat at our disposal for transportation to Galápagos on 15 July, and for the return of Mr. Eisenstaedt in mid-August.

- The Commander-General of the Navy coordinated the sailing schedule of the Government operated El Oro in order that we would not be inconvenienced in any way upon our arrival at the airport on Baltra Island. El Oro was awaiting our arrival and took us directly to Academy Bay.

- A modern speedy patrol boat was placed at the disposal of Eibl sad Bowman whenever we requested it. Captain Davalos and his crew cooperated with us in every way possible to make us comfortable and to land us wherever we requested, and often at “wild” anchorages.

- The government-operated wireless radio was placed at our disposal on numerous occasions, thus greatly expediting our field work.

- The Minister of Education was so keenly interested in the Galápagos project that he requested monthly reports of our progress and any recommendation we might wish to make for the establishment of wildlife reserves on Galápagos. It was explained that quick action on our part would make it possible, if we so wished it, to present to the Fall session of the 1957 Ecuadorian Congress, legislation in support of our recommendations.

- The National Committee for the International Geophysical year expressed much interest in the possibility of a research station on Galápagos, and wished to know if we envisioned oceanographic studies being carried out there. We indicated that we did.

- Ecuadorian scientists such as Dr. H. Acosta-Solis, Dr. Julio Arauz, and Prof. Gustavo Orces of the Comité Nacional de Proteccíon a la Naturaleza y Conservación de los Recuraos Naturales del Ecuador, have indicated their enthusiasm for our mission and hoped that a research station would materialize on Galápagos.

Chapter 3: Scientific Observations

In the following paragraphs I shall present some of the more significant biological observations made by the various members of our group. Systematic collections and observations were restricted for the most part to terrestrial vertebrates because of limitations of time. The writer also made notes -on the distribution of the vegetarian and prepared some herbarium specimens.

At the time of this writing (10 January 1958) not all of the collections on which many of the following observations are based, were at hand. For this reason certain conclusions are necessarily tentative, pending closer scrutiny of the specimens.

Plants

A relatively small collection of plants was made principally on Indefatigable Island, but a few specimens were also obtained on Jervis, Abingdon, Albemarle, Narborough, Chatham, Gardner-near-Hood, and Hood.

Of special interest was the procurement of specimens of the endemic species of Compositae, Scalesia Helleri, from the west side of Tortuga Bay on the south shore of Indefatigable Island. This curly-leaved, highly aromatic, shrubby species is known only from three previous collections; the first two from Barrington Island and the third, a previous collection from Indefatigable Island. Mr. Thomas Howell, California Academy of Sciences, who is an authority on Galápagos plants, has identified this new material.

Under the leadership of Mr. Rudolf Freund, an expedition was organized to penetrate the interior of Narborough Island for the purpose of making scientific observations in and around the large central crater. This expedition represents the fourth of its kind to reach the rim of the large central crater on Narborough Island. The first was in 1899 by Snodgrass and Heller who climbed to the north rim of the crater (Heller, 1903: 40). The second was by Mr. R. Beck in 1906 who examined the southeast rim of the crater having started from Mangrove Point (southeast corner of the island). The third expedition was organized by Mr. Otis Barton who in 1956, with the aid of Mr. Karl Angermeyer, climbed to the east rim of the crater from Point Espinosa (northeast corner of the island). Three of Mr. Barton’s carriers entered the crater and brought out fresh water from the lake.

Our expedition provided an excellent opportunity for the writer to compare the altitudinal distribution of the vegetation and compare it with that on the south-facing slope of Indefatigable Island. Regrettably, no herbarium specimens were obtained on Narborough (only seeds) because of severe weight and space limitations.

Although the north and northeast rim of Narborough crater is at an elevation of over 4000 feet, nonetheless no grass-fern formation is developed here as it is on the south-facing slope of Indefatigable island at 2000 feet elevation. Rather, the Scalesia tree forms a uniform forest growth about 8-10 ft. high at its maximum development, which is in marked contrast to the 50-60 ft. high Scalesia trees occurring on the south-facing slopes of Indefatigable Island. This situation may be due to differences in rainfall and wind exposure.

Some authors (viz. Lack, 1947: 78-79) have given the impression that “conditions” on the various islands of the Galápagos are more or less the same. It came somewhat as a surprise, therefore, to discover rather striking differences in the growth-form of the vegetation and the degree of dominance of certain species on the different islands visited, many of which, presumably, have similar climates, For example, on Indefatigable Island the thorny tree Parkinsonia forms a very inconspicuous element in the coastal vegetation, whereas on Duncan Island, all members of our group can attest to the dense tangle of dwarf trees of this species over large areas of the Island. Another example is the Opuntia cactus, which is so common throughout the arid coastal zone on Indefatigable Island that it forms one of the most conspicuous elements in the vegetation. On the north-facing slopes of Narborough Island this cactus is extremely rare, and we did not encounter our first tree until reaching the 1260 ft. elevation.

Wild tomato seeds were obtained from plants representing two distinct forms which were growing along the edge of the crater lake on Narborough Island (2325 ft.) This represents the first collection of its kind from this area and has been presented to Dr. Charles Rick of the University of California who actively engaged in genetical studies on Galápagos tomatoes.

About four miles inland from Academy Bay in the Scalesia forest zone and above, there has been a rapid clearing of the virgin forest for agriculture. During the interim of 4 years since the writer was last, in Galápagos, many great changes in the native vegetation have taken place. The farming community of Fortuna has now been extended to a distance of about one mile to the west of the main trail, and northward into the lower Miconia brush zone (above the Scalesia forest zone). It is nearly impossible to find an area of forest that has not been disturbed by man or his introduced animals in much of the area directly north of Academy Bay.

The zonation of the vegetation on the south-facing slope of Indefatigable Island, presents a unique biological situation far Galápagos. This is especially true for the Opuntia-Cereus forest around Academy Bay which is one of the tallest and densest of such formations on Galápagos, and the Miconia brush belt at elevations above the Scalesia forest. The latter formation has been the main obstacle in the penetration of the highest elevations on the Island.

Vertebrates

Fishes

Very few species of freshwater fishes have previously been taken from the Galápagos Islands. It was, therefore, with much interest that Hr. Freund and the writer collected four species of fish from freshwater pools about 1000 yards inland from Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island. Mr. Richard Rosenblatt, Curator of Marine Vertebrates, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, has identified these specimens as Gerrescinereus, Bathygobius lineatus, Philypnus maculatus and Electric pictus. He reports that the last two species are freshwater electrids which have never been recorded previously from the Islands. Bathygobius and Gerres are marine forms which are known to enter freshwater.

Circumstances surrounding the discovery of a small species of fish in the crater lake of Narborough Island is of some interest. Several medium sized fish hooks baited with fresh meat were hung from a float about 25 yards from the east shore of Narborough Lake. Several members of our group noticed a slight bobbing of the float and close examination through the 300mm. lens of my camera suggested that the motion might be due to winds, waves, or currents. No fish were caught by the books and note were observed along the shore in the murky green waters. On the last morning in camp the writer captured a large snake (Dromicus) by a clump of vegetation adjacent to the lake. This and other snakes were carried alive in my pack as our group climbed out of the crater. At the end of the first day's climb, all snakes succumbed to the heat and were preserved in formalin. For lack of space, the snakes were forced into a very small jar. Two days later when we sorted our collections, a small, near transparent fish, about one inch long, was discovered at the bottom of the jar which had contained the snakes. Mr. Rosenblatt informs me that it is a post-larval clinid, almost certainly Labrisomus and probably L. dendriticus, which is a Galápagos endemic. It is surprising to find a clinid being taken in freshwater since the family is not known for its euryhalinilty. The surface water in Narborough crater lake was definitely sweet although heavily tainted with sulphurous flavours. In view of the fact that the lake level is over 2000 feet above sea level, we are obliged to assume that there is no saltwater intrusion at the lake bottom, depth probably under 100 feet.

Reptiles

(1) Tropidurus. Van Denburgh (1913:164) reports that the lava lizard “appears to be nearly extinct on Charles Island”, which he attributes to the abundance of cats on the island. Eibl informed me that he obtained one on 21 September 1957, in the region of Black Beach.

(2) Conolophus. According to Van Denburgh and Slevin (1913:188) the land iguana was formerly abundant on James, Indefatigable, South Seymour, Albemarle, and Narborough Islands. “It is now rare on Albemarle and probably extinct on James and Indefatigable.”

None were observed on South Seymour Island by our group where Beebe (1924: 277) found them numerous twenty-five years previous. No doubt the apparent extermination of this iguana on South Seymour is attributable to the activities of the United States military on this island during World War II.

The California Academy of Sciences expedition in 1905-06 found the deserted burrows of what at one time must have been a large colony of land iguanas on Indefatigable Island. Van Denburgh and Slevin (1913:189) considered the species extinct on this Island. It was with much excitement, therefore, when Sr. Miguel Castro and Mr. Erling Graffer brought our group to a colony of land iguanas, hitherto unknown to science, at Conway Bay (northwest side of Indefatigable Island). We estimated the number on the colony at about 25.

Mr. Freund and I were guided to a lava tunnel by Herr Carlos Kubler, which was situated about one mile and a half inland from Academy Bay. On the floor of this half mile-long tunnel we found a large assortment of land Iguana bones, many of which were of very large proportions.

Land iguanas were observed on Narborough Island from the north coastal region inland to the top of the north rim, and down into the crater to the edge of the freshwater lake. Reports of land iguanas measuring nearly six feet long were not confirmed by our group. None we observed was much over three and one half feet in length but they were exceedingly numerous, and droppings were often seen on barren lava great distances from sources of food.

One female land iguana captured by Eibl on 11 September in the crater of Narborough, contained nine eggs with shells wall formed. Van Denburgh and Slevin (1913:191) reported large eggs in animals on Barrington Island on 22 October, whereas none had enlarged ovaries on 6 April. This observation supports the view that the land iguana breeds in the Fall season on Galápagos (dry season).

Van Denburgh and Slevin (1915:190) remark that the Academy Expedition found no burrows of land Iguanas on Narborough Island. Rather, the animals lived in cracks in the lava. Our group found active burrows in the soil from sea level to the north rim of the crater, and in the latter location they proved to be somewhat of a hazard while walking because of unexpected cave-ins.

We found the land iguana very common on Barrington Island, especially on a plateau inland from the northeast coast, presumably in the same area where the Academy expedition reported that “natives had visited the island and cleared out the entire iguana colony”. Inasmuch as they are very common there today, we can see how this species is able to re-establish itself even when the population has been almost completely killed off by hunters. Apparently, the animals are killed chiefly for their skins which are used for leather.

At Tagus Cove, Albemarle Island, I observed dried droppings which I thought were those of tortoise. However, since R. Beck observed 6-8 land iguanas here in 1906, possibly the species is still intact. No land iguanas were observed in the vicinity of James Bay, the only place our group landed on this island.

Heller (1903:85) believes that the extinction of the land iguana on islands where it formerly was abundant (i.e. Junes, Indefatigable) is due chiefly to the introduced dogs which destroy both eggs and adults. This may very well be true for wild dogs were once known to roam Indefatigable Island in considerable numbers and then rather suddenly disappeared. The land Iguana was thought to be extinct on this island. Human colonization has been too recent to account for the absence of the land iguana around Academy Bay and inland, where we may presume it once flourished, in view of the large number of cave skeletons we obtained. With the disappearance of the dogs, it might not be feasible to transfer stock from Conway Bay to Academy Bay and to other points around the island where possibly they once occurred.

Heller (loc. cit.) also remarks that “all the individuals observed were somewhat shy and would scamper to their burrows as soon as alarmed. This is undoubtedly an acquired habit due to their persecution by dogs.” The writer is skeptical of this statement for wild dogs were never known to occur on Islas Plaza or Narborough Island and at both these places the iguanas were found to be very shy and ferocious.

(3) Amblyrhynchus. In recent years there were no reports of the enormous herds of marine iguanas, which, in some localities, were so numerous that they more or less completely obscured the rocks (see Heller, 1903:90, and photo by Beck taken around 1900 in Beebe, 1924: Fig. 28).

Mr. Freund discovered a herd of several hundred marine Iguanas at Point Espinosa, northeast corner of Narborough Island in September, before the onset of territorial behaviour in the males. (See Life Magazine, 8 September 1958, page 67.)

On Hood Island in September and October individuals were found in their brilliant colours distinctive of breeding condition. Slevin remarks that “the iguanas are now very brightly coloured—green, red, and black” on 5 February 1906 (Van Denburgh and Slevin, 1913:193), and Eibl-Eibesfeldt (1956) described this population as a new race.

No marine iguanas were found on Charles Island in the region of Black Beach and none were seen by any of the members of the Academy expedition in 1905-06 (Van Denburgh and Slevin, 1913:193).

(4) Dromicus. In 1952-53 the writer found no snakes on the south side of Indefatigable Island where once they were known to occur in abundance. At that time feral cats were also plentiful. In 1957 several snakes were collected, and coincidentally the cat population was very low due to a recent poisoning campaign.

Van Denburgh (1912:336), under “Suggestions to Future Students”, remarks that “future collectors in these islands should strive to secure specimens of the snake of Chatham Island, if such there be”. It was of much scientific interest, therefore, to learn that Sr. Luis Perez and his brother from Guayaquil had collected a specimen or two of snake around Wreck Bay, Chatham Island during November, 1957. These were taken to the museum at the Colegio San Jose, in Guayaquil. Eibl also obtained representatives of this island form whose systematic position is yet to be determined. The writer obtained one snake from Bartholomew Island from which no snake has previously been taken.

Two specimens of snake were obtained on Albemarle Island from which island existing museum collections have few representatives. Eibl found one snake in September at Tagus Cove, and the writer obtained one from Cartago Bay in August.

As noted previously, snakes were found in the crater of Narborough Island and one of these regurgitated a small fish, presumably caught in the crater lake. The presence of a fish in the stomach of Dromicus represents a new item in the diet of this reptile. The tail of Tropidurus. the foot and tail of a gecko, and grasshoppers, have all been previously reported in the stomachs of Galápagos land snakes (see Van Denburgh, 1912: 341, 353, and 355).

(5) Sea snake. Mr. Slevin reports the Academy group observed a bicolour sea- snake (Pelamydrus platurus) about 20 inches in length, black on top, and bright yellow below, on the open ocean between Chatham and Hood island on 24 February 1906 (Van Denburgh, 1912:355).

On 20 November 1957, the writer observed a bright yellow coloured snake alongside our boat which was anchored in Academy Bay. The details of coloration could not be discerned since the observation was made after dark and the animal was visible only for brief moments in the light from the deck. The crew was aroused and made an unsuccessful effort to capture the snake. This observation constitutes the second known record of the sea-snake in Galápagos waters.

(6) Gecko. Our observations on geckos have added little that is new concerning the biology or distribution of this species.

(7) Tortoise. The Galápagos Islands were appropriately named the “Isles of the Tortoises.” From the time of their discovery by the Spaniards early in the sixteenth century, down to the middle of the nineteenth century, their outstanding feature has been the presence of great numbers of land tortoises of gigantic size. No other product of the lonely archipelago was of much more than passing interest to navigators except the fur seals, of which they soon disposed (Townsend, 1925). in the minds of many people “Galápagos” is synonymous with tortoise, both literally and figuratively speaking, and mental images of reptilian monsters weighing as much as a ton are prompted by the numerous tales in historical writing about these islands.

Thanks to the efforts of the late Dr. C. H. Townsend who visited Galápagos on several occasions, we now have good data on the numbers of tortoises taken by whalers in past centuries. For example, he has reported on the log-book records of some 105 whaling ships which carried away over fifteen thousand tortoises between 1811 and 1844, or an average of 122 tortoises per vessel! (See Townsend, 1925, 1928.) These figures by no means represent the entire take by whalers, since during this period there were over 700 vessels in the American whaling fleet alone.

in addition there were British whalers, buccaneers, sealers, and merchantmen who frequented Galápagos shores. As S1evin (1935:10) aptly remarked, “the slaughter was appalling”, and it has not ceased even to this day! The search for Galápagos has been so persistent and so devastating that except on Albemarle and Indefatigable Islands, it requires intense hunting by a person very familiar with the habits of tortoises, to find one.

Dr. George Bauer who visited the Galápagos Islands in 1891 has remarked that ten million tortoises may have been taken from the islands since their discovery, a figure which this writer believes to be much too large. Townsend (1925:70) considers it to be within “safe limits” to credit American whalers with taking not less than one hundred thousand tortoises after 1830!

During the course of our 1937 Galápagos reconnaissance a special effort was made to learn as much as possible about present numbers of tortoises on the various islands where they were once known to occur in abundance.

According to the last monographer of this species (Van Denburgh, 1914), tortoises were once known to occur on the following 11 main islands: § Abingdon, James, Jervis, Duncan, Indefatigable, Barrington, Chatham, Hood, Charles, Narborough, and Albemarle, they have never been known to occur naturally on Tower, Bindloe, Culpepper, and Wenman islands. According to the best available Information in 1914, based primarily on the findings of the California Academy of Sciences' expedition in 1905-06, Van Denburgh gave a “status” for each island population. These are compared with the status as the writer considers it to be in 1957.

§ The author's original text follows the above island sequence. For this online version, the islands have been placed in alphabetical order. In the following table, column 1 gives the English name used by Bowman, which also serves as a link to additional information below; column 2 gives the official (or, official/popular) name for the same island. In the descriptions which follow, Bowman sometimes includes two or more numbers for the quantity of tortoises, but offers no explanation of the reason for this.

| Island | Status in 1914 | Status in 1957 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abingdon | Pinta | rare | very rare |

| Albemarle | Isabela | numerous to rare | numerous to rare |

| Barrington | Santa Fe | extinct | extinct |

| Charles | Santa María/Floreana | extinct | extinct |

| Chatham | San Cristóbal | nearly extinct | very rare or extinct |

| Duncan | Pinzón | fairly abundant | rare |

| Hood | Española | very rare | very rare |

| Indefatigable | Santa Cruz | not rare | fairly numerous |

| James | San Salvador/Santiago | rare | very rare or extinct |

| Jervis | Rábida | very rare | very rare or extinct |

| Narborough | Fernandina | very rare | unknown (See text) |

It should be kept in mind that the 1957 estimates of abundance are based on much poorer scientific evidence than those presented by Van Denburgh, but the writer has tried to be conservative. In general our findings suggest that, for the most part, existing populations of tortoises are probably smaller than in 1905-06. Because of better penetration of the interior of Indefatigable Island in 1957 than was possible in 1905-06, I think the tortoise population is greater on this island than was suspected by the Academy expedition or as suggested by log-book records of whaling ships. It would be scientifically valuable to learn through intensive field work if any population of considerable size still remains on Abingdon, James, Jervis, Chatham, and Narborough.

In the following pages I have presented a brief summary of the main published records of the removal of tortoises from the various islands in addition to an elaboration of the evidence, in most cases very feeble, on which my estimate of “status in 1957” is based.

ABINGDON ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Abingdon Island. All records are from Townsend (1925, 1928), unless otherwise indicated.

| 1822 | “Plentiful on Abingdon” (Van Denburgh, 1914:219) | 1853 | 3 |

| 1832 | 8 | 1854 | 3 |

| 1835 | 12, 10 | 1862 | 4 |

| 1837 | 142 | 1867 | 1 |

| 1843 | 67 | 1875 | 4 (Van Denburgh, 1914: 227 |

| 1845 | 7 | 1884 | 1 |

| 1847 | 1, 3 | 1888 | “some” tortoises obtained |

| 1848 | 23, 10 | 1889 | none seen by Heller (1903: 59) who states “probably now nearly extinct” |

| 1849 | 6, 5 | 1901 | 2 (Van Denburgh, 1914: 237) |

| 1852 | 5 | 1905-06 | 3 (Van Denburgh, 1914:298) |

| Van Denburgh (1914:243) designated the Abingdon Island tortoise as “rare”. | |||

Status of Abingdon Tortoise in 1957. Eibl and I climbed the 2000 ft. cliffs on the western side of the island on 15 August and penetrated the dense vegetation almost to the highest peak. We saw no animals but observed one or two paths of somewhat matted underbrush suggesting the trail of a tortoise. I consider the tortoise to be very rare, if not close to extinction on Abingdon Island.

ALBEMARLE ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Albemarle Island. All records are from Townsend (1925, 1928), unless otherwise indicated.

| 1833 | 9 | 1853 | 150 |

| 1835 | 2, 67 | 1854 | 1 |

| 1836 | 23 | 1855 | 14, 11 |

| 1838 | 8 | 1857 | 13 |

| 1839 | 20, 7 | 1858 | 24 |

| 1840 | 113 | 1859 | 7 |

| 1841 | 10, 12, 47, 24 | 1860 | 81, 122, 14, 56+ |

| 1842 | 64, 36, 10, 5 | 1861 | 6, 41 |

| 1844 | 4+, 9 | 1862 | 95, 63 |

| 1845 | 69, 150, 3 | 1872 | 36 |

| 1846 | 2, 1 | 1875 | “Still abundant on the southeast end of Albemarle and tolerably numerous at Tagus Cove (Slevin, 1935:11) |

| 1848 | 75 | 1901 | 18 (Van Denburgh, 1914:237) |

| 1849 | 2, 63 | 1902 | Oil hunters as [sic, at] work on Villamil Mt. southern Albemarle |

| 1851 | 2 | 1905 | “Very few large tortoises found on Villamil Mt.” (Slevin, 1935:11) |

Van Denburgh (1914:243) gives the status of the tortoise on Albemarle Island as follows: Villamil, abundant; Iguana Cove, numerous; Tagus Cove, fairly numerous; Banks Bay, fairly numerous; and Cowley Mt., rare.

Status of Albemarle Tortoise in 1957. Our group was informed by Sr. Gonzolo Garcia that inland from the north shore of Albemarle Island between Point Albemarle and Cape Berkeley tortoises are still numerous. Eibl found a mummified specimen of a newly-hatched tortoise a short distance inland from Tagus Cove. Four years earlier (1953) he found another small mummified tortoise in the same general area. Along the ridge of the crater containing the salt water lake by Tagus Cove, I discovered two dried droppings composed of plant material, presumably of tortoise, although possibly of land iguana, and there were trails suggestive of those made by tortoises in evidence here.

Mr. Freund and I saw one or two live tortoises at Wreck Bay that were being kept as pets and which were supposed to have been found on Albemarle Island. We were told that tortoises are still to be found in the highlands north of Villamil in the vicinity of the penal colony, but these are quite reduced in numbers. Thus, tortoises are still plentiful in certain localities on Albemarle Island, particularly those regions in the northern port of the island that are not readily approached by boat. In the immediate vicinity of settlements they are very rare.

BARRINGTON ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Barrington Island.

1839 22 (Townsend, 1925)

1853 1 (Townsend, 1925)

The California Academy of Sciences expedition found only old eggs and tortoise remains on Barrington Island so that Van Denburgh (1914:243) considered the population to be extinct. In 1957 learned that colonists from Academy Bay released two small tortoises (obtained from Indefatigable Island) on Barrington Island. One of these was discovered by yacht people in July of the same year.

Status of Barrington Tortoise in 1957. No signs of tortoise were observed by our group in 1957 and the species is considered to be extinct. No doubt the early disappearance of this island population of tortoise is due to the fact that the island la not densely covered with vegetation, making for easy penetration of the interior, and also to the large number of feral goats which might have been food competitors.

CHARLES ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Charles Island. All records are from Townsend (1925, 1928), unless otherwise Indicated.

| 1812 | 400-500 (Townsend, 1930:141 | 1835 | 50, 40 |

| 1824 | 394 | 1837 | 24 |

| 1828 | 100 | 1847 | “some terrapin” |

| 1831 | 155, 179 | 1848 | “got some terrapin” |

| 1832 | 226+ | 1875 | Reported extinct on Charles (Slevin, 1935:11 |

| 1833 | 235 | 1882 | 5 |

| 1834 | 100, 350, 100 |

Charles Darwin who visited this island in 1835 stated that the main animal food of the colonists was derived from the tortoise (Townsend, 1925:63). According to the log-book records of 79 whaling ships examined by Townsend (1928:157), the last tortoises were taken from Charles Island in 1837. Heller (1903:53) considered the Charles Island tortoise to have been extinct since 1840, stating that the penal colony which was established on the island by the Ecuadorian Government in 1829 had brought about their extermination directly because the animals were killed for fresh meat, and indirectly, as suggested by Broom (1929:313), by the feral dogs and pigs. Broom (1929:313) states that probably the native tortoises were extinct by 1850, any specimens collected after that date are most likely to have been animals brought from neighbouring islands. The California Academy of Sciences expedition of 1905-06 obtained no specimens from Charles Island. In 1928 several barrels full of tortoise bones were obtained from a cave (Townsend, 1928:156, Broom, 1929:313).

Status of Charles Tortoise in 1957. Extinct.

CHATHAM ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Chatham Island. All records are from Townsend (1925, 1928), unless otherwise specified.

| 1813 | 100+ (Slevin, 1935:10) | 1848 | 54, 70, 200, 4, 177 |

| 1834 | 8 | 1849 | 130 |

| 1836 | 20 | 1850 | 150, 110 |

| 1837 | 240 | 1851 | 90 |

| 1838 | 67 | 1852 | 107, 47 |

| 1840 | 59, 65, 115 | 1853 | 315, 13 |

| 1841 | 102 | 1854 | 43 |

| 1842 | 118, 107, 30 | 1855 | 152, 28, 4, 310 |

| 1843 | 262 | 1859 | 78, 70 |

| 1844 | 24, 130, 100 | 1861 | 188, 50, 42, 105, 50 |

| 1846 | 14, 190-, 120 | 1863 | 208 |

| 1847 | 100, 4, 100 |

In 1875 few tortoises were reported surviving on Chatham Island (Slevin, 1935:11); and the California Academy of Sciences expedition collected only two live animals in 1905-06 (Van Denburgh, 1914:326), the latter author (loc. cit. p. 243) considering the Chatham Island population “nearly extinct” in 1914.

Status of Chatham Tortoise in 1957. Mr. Rudolf Freund and the writer purchased two live tortoises at Wreck Bay in October, and these animals were reportedly taken from Chatham Island. Since there was some reason to trust the accuracy of this report, the island population may still be intact; but it is probably near extinction.

DUNCAN ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Duncan Island. All records are from Townsend (1925, 1928), unless otherwise indicated.

| 1848 | 50 | 1891 | 8 (Van Denburgh, 1914:228) | |

| 1850 | 131 | 1897 | 29 (Van Denburgh, 1914:233) | |

| 1855 | 17 | 1900 | 4 (Van Denburgh, 1914:237) | |

| 1865 | 208 | 1901 | 5 (Van Denburgh, 1914:237) | |

| 1888 | 18 | 1905-06 | 86 (Van Denburgh, 1914:311 | |

| 1891 | 1 | 1923 | 1 (Beebe, 1924:224) |

We learned from the colonists at Academy Bay that in 1954 the Walt Disney Photographic expedition discovered live tortoises on Duncan Island.

Status of Duncan Tortoise in 1957. Our group searched the east slope of the island and the top crater for tortoises but none were found. Mr. Rudolf Freund later made two separate trips to the south slopes of the island, where the California Academy of Sciences expedition found most of their specimens. After much hard labour one animal was found but not without the help of Sr. Gilbert Moncayo, son of a veteran tortoise hunter. In view of the effort expended to locate this one animal, the tortoise on Duncan Island should be considered “rare.”

HOOD ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Hood Island. All records are from Townsend (1925, 1928); unless otherwise indicated.

| 1831 | 335, 250, 86 | 1844 | 20, 14 |

| 1832 | 50 | 1846 | 7 |

| 1834 | 237 | 1847 | 67 “got but few terrapin” |

| 1835 | 65 | 1849 | 1 |

| 1838 | 136 | 1853 | 7 |

| 1839 | 12 | 1875 | “number so greatly reduced they were no longer hunted.” Slevin, 1935:11) |

| 1840 | 45 | 1905-06 | 3 (Van Denburgh, 1914:315-316) |

| 1842 | 173, 5 “terrapin very scare” [sic] | 1929 | 2 taken by Pinchot expedition (Townsend, 1930:142) |

| 1843 | 100 | ||

| Van Denburgh (1914:243) designated the Hood Island tortoise as “very rare.” | |||

Status of Hood Tortoise in 1957. Mr. Rudolf Freund purchased one small live tortoise at Wreck Bay in October which was reported to have been taken on Hood Island. The writer was on Hood Island on 23-24 September and 16 October, but discovered no signs of tortoise. Sr. Gonzolo Garcia of Wreck Bay reports tortoises still occurring on Hood, although they are very rare.

INDEFATIGABLE ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from Indefatigable Island. All records are from Townsend (1925), unless otherwise indicated.

| 1812 | tortoises in abundance (Townsend, 1930 | 1845 | 45 |

| 1825 | 187 (Van Denburgh, 1914:219) | 1848 | 36 |

| 1833 | 44 | 1824-49 | “There are before me records of certain whaleships that took 753 tortoises from Indefatigable Island between 1824 and 1849.” |

| 1834 | 140, 12 | 1875 | “numbers so greatly reduced they were no longer hunted.” (Slevin, 1935:11) |

| 1836 | 2 to many | 1901 | 10-11 (Van Denburgh, 1914:237 |

Heller (1903:51) states that “The form on Indefatigable has only recently become extinct”, whereas Van Denburgh (1914:243), reporting on the California Academy of Sciences 1905-06 expedition, which obtained 46 tortoises on Indefatigable, considers it “not rare.” In 1952-53 the writer encountered a small tortoise in the highlands northeast of Academy Bay.

Status of Indefatigable Tortoise in 1957. This island has been visited less frequently by sailors than most of the other large islands, which may help to account for the presence of a fairly large population of tortoises to this day. From 20-23 July 1957, our group visited the “Tortoise Country” approximately 7 miles northwest of Academy Bay, and approximately 15 hours by trail, elevation 500 feet. In this region of mid-transition zone forest there are numerous small and large ponds and open grassy areas where we encountered 3 large tortoises, one of which was estimated to weigh over 500 pounds by a veteran tortoise hunter, Sr. Cecil Moncayo. Sr. Moncayo also mentioned that this was not the largest specimen he has seen on Indefatigable Island. We found the skeletal remains of tortoises strewn about the forest in this area, attesting to the intensity of the slaughter of this animal for food and oil in recent years.

Mr. Freund and I discovered the skeletal remains of two tortoises in a lava tunnel about one and a half miles north of Academy Bay. On 29 September 1957, a small tortoise was discovered by dogs on the Kastdalen farm, approximately five miles north of Academy Bay, elevation 750 ft. This was the first tortoise ever found by the Kastdalen family on their property during the 22 years of continuous residence here. Sr. Sotamayor collected several skeletons from an area several miles west of Tortuga Bay called “La Fe.” One of the carapaces measured almost four feet long (linear length). In the coastal situation it is not difficult to find live tortoises, and Sr. Sotamayor captured 5, all about one foot in length, one of which was brought alive to Berkeley, California for study. Eibl found a shell of a small tortoise (about 10 inches long) which had been broken open presumably by a pig. Sr. Sotamayor stated that pigs frequently attack tortoises in this manner.

In view of the large extent of suitable tortoise habitat on the south and southwest slopes of the island, it may be assumed with confidence that the tortoises are still fairly numerous, although inroads by oil hunters on the population are a constant threat to the species. Next to Albemarle Island, Indefatigable Island probably has one of the largest remaining populations of tortoise on Galápagos.

JAMES ISLAND

The following are the main published records of the removal of tortoises from James Island, all records are from Townsend (1925, 1928), unless otherwise indicated.

| 1812 | Capt. Porter's crew loaded one of his ships with tortoises that “would weigh about fourteen tons” (Townsend, 1930:141) | 1838 | 12- |

| 1813 | “Land tortoises are found here in great abundance” (Slevin, 1935:11) | 1841 | 179, 93 |

| 1831 | 55 | 1842 | 10 |

| 1834 | 23+ | 1845 | 58, 20 |

| 1835 | 124, 68, 35 | 1875 | “numbers so greatly reduced that they are no longer hunted” (Slevin, 1935:11) |

| 1836 | 13-, 118 | 1905-06 | 5 (Van Denburgh, 1914: 321-322) |

| 1837 | 224 | ||

| Van Denburgh (1914:243) designated the James Island tortoise as “rare”. | |||

Status of James Tortoise in 1957. Local tortoise hunters now consider the James tortoise to be extinct, even though there are vast areas in the highlands, very inaccessible because of intervening lava beds, where tortoises eight still exist. Slevin (in Van Denburgh, 1914:321-322) writes as follows about the James Island terrain: “We went in after tortoises about five miles northwest of Sulivan Bay. The country is extremely rough—the worst we have encountered since we arrived in the Islands. It was very difficult to get out the ones we did. No wonder people don't find tortoises on James I”—our group explored only the coastal area about James Bay and a small inlet (called “Crab Point” by local fishermen) a few miles south of James Bay, but we found no signs of tortoises here. They are probably very rare or extinct on James Island.

JERVIS ISLAND

The first and only published report of tortoise on Jervis Island is that of Van Denburgh (1914:351-353) who described the one specimen captured by the California Academy expedition in 1905-06. None has been reported since.

Status of Jervis Tortoise in 1957. Our group spent two days on Jervis Island covering such of the northeast coastal region, almost to the top of the island, without discovering any signs of tortoise. Presumably the species is now very rare or extinct on Jervis Island.

NARBOROUGH ISLAND

Only once [sic, one] specimen of tortoise has been taken from Narborough Island by scientists, and this was obtained by Rollo Beck in 1906 while leader of the California Academy of Sciences Galápagos expedition. It has been suggested by Townsend (1925:66) that tortoises probably were largely destroyed on this island from time to time by lava flows and by intense heat. However, I am of the opinion that due to the formidable expanse of lava which surrounds the green highlands, especially in locations adjacent to anchorages, few people have been willing to run the risk presented by the extended trek inland to search for tortoise. The only other collectors known to have penetrated the interior of Narborough Island previous to Beck were Heller and Snodgrass (1903:40) who climbed to the summit of the crater's north rim. They observed no tortoises. Our group in 1957 climbed the crater in essentially the same location as Heller and Snodgrass, and we did not find any tortoises or signs of them, even inside the main crater. Presumably the southern slopes would be more productive since they are considerably moister, but we were unable to extend our survey into this area. It was on the southeast slope about 1000 feet from the rim of the crater where Beck found his only specimen. Because no one has surveyed the most likely areas on Narborough Island where tortoises may occur, it is impossible to formulate a status for this species on this island. Because the green zone is quite extensive on the south-facing slope, we might predict that a fairly large population exists there, unknown to science.

Summary of Tortoise Occurrences in 1957

Tortoises are still fairly plentiful on Albemarle and Indefatigable Islands, but quite rare on Duncan, Hood, Abingdon, and possibly Chatham Islands, with the status on Narborough Island undetermined.

Birds

The following are but a few of the observations on birds made during 1957.

(1) Penguin and flightless cormorant. At Pt. Espinosa, northeast corner of Narborough Island, numerous penguins and cormorants were encountered. The penguin was suspected of nesting in the lava crevices because of their distinctive calls emitted in the region of the shore. Also, the writer observed copulation while the birds were in the water, in late September. Mr. Rudolf Freund had the good fortune to discover a nest of the penguin containing two downy young at Iguana Cove, Albemarle Island, on 17 September. This marks the second nesting report of this species. The first was made by Couffer (1957) at Point Espinosa in August, 1954. The writer observed nearly full-grown young penguins, still covered with grey down feathers, at a small island in Elizabeth Bay,§ west of Albemarle Island, on 16 September.

§ Probably, one of the Marielas.

The flightless cormorant was found nesting at Pt. Espinosa in September. Several nests with downy young were scattered about the barren lava. Copulation was observed once, and this took place on land.

(2) Galápagos pintail. In September, while our group was camped on the shore of the crater lake, Narborough Island, we saw numerous ducks feeding on the floating mats of green algae. Here the writer observed copulation, and other members of the group discovered some nests in the rushes containing eggs, and downy young were seen on the water.

(3) Bird colonies Point Cevallos, southeast corner Hood Island. The writer visited the bird colonies in September and October. #8220;Courting” groups of Albatross were noted along the coast and one mile inland near the now defunct radar station. On both occasions half-grown downy young were seen walking about. No active nests were observed. The largest colony of masked boobies (Sula dactylatra) encountered on Galápagos were found perched on the ocean-facing cliff at Pt. Cevallos. No nests were found and the birds intermingled with the frigate-birds (Fregata minor) whose nests contained half-grown young and were situated on the shrubby vegetation close to the cliff. Nests and eggs of the fork-tailed gull (Creagrus furcatus) and red-billed tropic bird (Phaethon aethereus) were found along the cliff in October. The latter nested in small wind eroded pockets in the sedimentary tuff. Pigeons (Nesopelia) were exceedingly common and tame on Hood Island. The longest billed form of mockingbird (Nesomimus) found on Hood Island was seen to puncture the eggs of the fork-tailed gull when the adult bird was frightened from the nest.

(4) Bird colonies at Darwin Bay, Tower Island. When our group visited this bird “sanctuary” in August, we found large numbers of frigate-birds (Frigata minor) and boobies nesting. Three species of booby were present: the commonest was the red-footed (Sula piscator), the blue-footed (Sula nebouxii), masked (Sula dactylatra) species in much fewer numbers; all three species were nesting (i.e. with eggs or young). No nests of the frigate-bird were found containing eggs, but many had young of various ages from about one week old to nearly fully-fledged birds. None of the adult males were seen to inflate the gular pouch, although members of the yacht Utopia reported seeing inflated pouches at this same locality in the preceding month. According to Beebe (1924:319) an inflated pouch is correlated with an empty nest whereas a deflated pouch is correlated with an egg in the nest. As on Hood Island, the pigeons were exceedingly tame and abundant on Tower Island.

(5) Finches. Of special interest to the writer were the finches, which group he had studied in considerable detail in 1952-53, chiefly at Academy Bay. The present reconnaissance permitted him to become acquainted with all the species, and the following were encountered for the first time in 1957: Geospiza conirostris, Geospiza difficilis, Camarhynchus pauper, and Cactospiza heliobates.

Geospiza conirostriswas found to be very common on Hood Island, and less abundant on Tower Island. Among the finches of Tower Island, Geospiza difficilis is second in abundance to Certhidea olivacea.

David Lack in 1938-39, and the writer in 1952-53 did not encounter Geospiza difficilis on Indefatigable Island, from Academy Bay inland to Fortuna, in which region they were observed as late as 1935 by Harry Swarth of the California Academy of Sciences. Extensive searching and collecting in all sections of Indefatigable Island failed to turn up this species, which is now presumably extinct. The existence of a large population of Geospiza difficilis (race undetermined as yet) on Narborough Island was established in September 1957. Previously this species was recorded with some uncertainty from this island (see Swarth, 1931:181, and Lack, 1947:20).

On a four-hour-long walk into the highlands of Charles Island from Black Beach, during a rainstorm, the writer collected several examples of Camarhynchus pauper, which species occurred sympatrically with C. psittacula and C. parvulus in the dense forest tangle of introduced guava and lemon trees. While returning to the beach the writer spotted a large-billed Geospiza, which he shot at very close range. This specimen is, without a doubt, assignable to Geospiza magnirostris. Furthermore, some of its bill dimensions overlap with those collected by Charles Darwin in 1835. There has been such uncertainty about the exact locality from which Darwin obtained his exceedingly large-billed specimens, i.e. Charles, Chatham, or James island (see Swarth, 1931:146-150). Swarth thinks it unlikely that Darwin's specimens could have come from Charles Island since no large-billed finches have since been found upon this island. With this “re-discovery” of G. magnirostris on Charles Island, and especially an individual that is so large in bill dimensions, there is good reason to think, contrary to the views of Swarth (loc. cit.), that Darwin probably did collect his specimens on Charles Island, as he implies in his Journal.

(6) Rails. On the basis of information related to me by Mr. Alf Kastdalen and specimens obtained in 1953 and 1957, it is now firmly established that two species of rail are resident on Indefatigable Island.

In the grasslands atop the island the black rail (Lateralluss pilonotus) was seen and a specimen in formalin obtained for me by Alf Kastdalen. In 1953 I collected two individuals of a somewhat larger red-legged rail, clearly referable to the species Neocrex erythrops, hitherto unreported on Galápagos.

(7) Flamingos. Fourteen birds were observed by the group in 1957, as follows:

James Island, James Bay

Crater Lake, 1 August, 2 birds.

Lagoon, 1 August, 5 birds.

Indefatigable Island

Conway Bay, Lagoon, 4 August, 2 birds.

Tortuga Bay, Lagoon, 12 October, 5 birds.

Mr. Freund reported seeing a captive bird at Villamil, Albemarle Island in September.

(8) Larus fuliginosus. To the disappointment of the Writer we did not obtain any evidence to indicate the whereabouts of the breeding grounds of the lava gull, whose eggs and nest are still unknown to science.

Bobolink. One immature bird was given to the writer by Mr. Alf Kastdalen who found it dead on their farm located approximately 5 miles north of Academy Day, elevation 750 feet. Mr. Kastdalen has observed adult birds on the farm during August and September of 1957. Swarth (1931:136) lists the three previous records of this species for Galápagos. This is the first report of this species on Indefatigable island.

Mammals

(1) Native rodents. The following species of rodents have been reported from the Galápagos Islands (Orr, 1938:303-304):

| Barrington | Oryzomys bauri |

|---|---|

| Chatham | Oryzomys galapagoensis |

| Indefatigable | Nesoryzomys darwini |

| James | Nesoryzomys swarthi |

| Indefatigable and South Seymour | Nesoryzomys indefessus |

| Narborough | Nesoryzomys narboroughi |

Oryzomys bauri was found to be exceedingly common on Barrington Island in September and October when both snap and live traps were set along a dry wash leading from the northeast corner of the island.

Nesoryzomys narboroughi was trapped at Pt. Espinosa on lava beside clumps of Cereus nesioticus on which the animals fed. It was also common on the rim of the crater (4150 ft.) beneath Scalesia trees, and along the edge of the crater lake (2325 ft.) in the rushes.

(2) Introduced Rodents. The following species of introduced rodents have been recorded on Galápagos (see Heller, 1903:235-238):

| Albemarle, Chatham, Duncan | Rattus rattus rattus |

|---|---|

| Albemarle, Charles, James | alexandrinus |

| Chatham | Mus musculus |

Through field observations and trappings I have recorded R. r. rattus on Duncan Island in July,R. r. alexandrinus at Academy Bay and inland from July to October, and Mus musculus on Indefatigable Island (July), Charles Island (September), South Seymour Island (July).

Heller (1904:236) states that “In no locality in the archipelago do any species of Mus (Rattus and Mus) [sic, ?] occur with the indigenous species of Oryzomys and Nesoryzomys. This is probably due to the extermination of these latter species by hardier introduced forms of Mus, and by cats.”

On Charles Island, approximately three miles east of Black Beach, 1300 ft., on 20 September, I observed numerous house mice running around the forest floor in the middle of the day (sky overcast, rain falling) quite undisturbed by my presence.

Along the main trail to the highlands from Academy Bay I frequently saw Rattus running between the crevices in the lava, and frequently one would find a sickly or dying animal on the trail. The population of Rattus and Mus was so high that all traps in a line often would catch one, and sometimes two animals, for two nights in succession! About three years ago the residents began setting out poisoned bait (“ten-eighty” poison on bananas) in an effort to reduce the rodent population. This action, seemingly, has had little effect on the rodent population but has brought about a remarkable decrease in the feral house cats as well as the local pet dogs and cats. This in turn may help to account for the increase in the wild snake population around Academy Bay.

Mr. Freund and I picked up many skulls of a small rodent, possibly Nesoryzomys darwini from a lava tunnel about 1½ miles north of Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island. However, no native rodents were trapped on this island in 1957.

(3) Feral animals. So far as the writer is aware there is no published report in which an organized account of the distribution of escaped domestic animals is given. On the basis of our observations and information obtained from local residents, we learned that at present (1957) donkeys, goats, cattle, pigs, and cats are running wild on the islands of Indefatigable, Chatham, Charles, and Albemarle. James Island has the same complement except that it lacks cattle and possibly also cats. Albemarle possesses wild dogs, and these may also be present on Chatham and Charles. They are now apparently extinct on Indefatigable Island (last reported in 1935). Hood and Barrington islands support large populations of goats. South Seymour Island once had many goats but these seem to have been killed off completely with the building of the military base in 1942.§ Duncan, Jervis, Abingdon, Bindloe, Tower, South Seymour, and Narborough islands are presently free of feral animals.

§ The goats were not killed off while the American troops occupied South Seymour Island (now, as then, Isla Baltra). According to a Time Magazine report, Galápagos goats idled nearby when the base was turned over to Ecuador at the end of WWII.

(4) Fur seal (Arctocephalus australis). Townsend (1934:47) has published a compilation of some of the seal catches on Galápagos, and the following is a summary of his data:

| 1816 | 8,000 | 1885 | 1,000 |

| 1825 | 5,000 | 1887 | 1,200 |

| 1843 | 14 (Narborough) | 1897-1899 | 224 |

| 1872-1880 | 6000 | 1906 | 1 |

| 1880 | 261 (Albemarle, Culpepper, Narborough, Tower, Wenman) | 1932-1933 | 8 |

| 1882 | 800 | (total) | 22,508 |

The history of the reduction of the Galápagos fur seal, of which the foregoing records are but a partial indication, has been similar to that of the Guadalupe Island seal, namely, the unrestricted slaughter of male and female, old and young alike, whenever and wherever found. The history furnishes further proof of the fact that the fur seals cling to their ancestral and accustomed breeding grounds, that the re-establishment of the species would undoubtedly result from a complete protection of these places and the result would be the building up of a valuable seal fishery for the future (see Townsend, 1899:272-273).