|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

19 |

| XVII. – LINSEED MEAL AND MUSTARD PLASTER. | |

| Take 2 ozs. Of linseed meal and mix with sufficient boiling water, then add 2 ozs. Mustard, previously mixed with 3 ozs. Luke warm water. Mix the two together, and apply to the chest in Bronchitis or other inflammations. |

|

| XVIII. – TURPENTINE FOMENTATIONS. | |

| Wring a sufficiently large piece of flannel out of hot water. Soak in turpentine and apply quickly. Cover over with anything to keep the heat in, and let it remain for 20 minutes.Remove the fomentation and apply some olive oil. |

|

20 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

NOTES RELATING TO THE USE OF MEDICINES, &c.

—————

Whoever has the charge of the Medicine-Chest must take care that it is kept clean and in good order, and that the various bottles and jars are kept closely stopped and tied over, and in their proper places. Almost all medicines are damaged by exposure to the air, even in a very slight degree.

All scales and weights, measures, and other things used in measuring or mixing the medicines, should be carefully cleaned after use, because the smallest quantity of any one medicine becoming mixed with another may spoil it, or seriously interfere with its action.

In measuring the medicines, it is always better to be strictly accurate. In treating diseases, the proper quantity is often of as much importance as the kind of medicine to be used.

Remember always, in giving medicines, that it is safer to give too little than too much.

The lancets should always be most carefully cleaned after use. The best way of wiping the blade is to lay it along one scale of the handle, and wipe it from heel to point; then lay it along the other scale, and wipe the other side in the same way. Never let the point touch anything hard.

One lancet should be kept specially for use in opening abscesses, because a blade that has been wet with foul matter may infect another wound, even after it has been apparently dried and cleaned. Similar precautions should be observed with the bougies, catheter, &c., and any instrument that has been in contact with the fluids of the body.

All lint, plaster, and dressings, that have been applied to discharging wounds, should be thrown away immediately after use.

The Bed-pan should be well cleansed with Carbolic Acid (No. 9) immediately after use. A small quantity of the acid (mixed in water as directed) should be put into it before use.

|

|

GENERAL RULES FOR KEEPING THE

SHIP HEALTHY.

—————

The first object is to sail with a healthy crew. Every sickly or diseased hand taken on board is a double loss: he not only requires other men to take his share of the work of the ship, but takes up more of their time in attendance upon him. Masters of ships, therefore, have a strong interest in availing themselves of the 10th section of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1867, which enables them to procure a medical inspection of any man applying for employment in their ships, before entering him upon the articles. Unless this is done, there is always a risk of discovering serious or disabling maladies among the crew before the ship has been many days at sea.

The next thing is to sail with a clean ship. The following extract from an old work entitled "Vandeburgh’s Mariner’s Medical Guide" may still be useful, though no doubt much improvement has taken place in ships of the better class since the time when it was written.

"For the better information of seamen in general, I shall consider a ship being discharged in dock, and going to prepare for taking a cargo to the East or West Indies. We will suppose the ship has lately returned from one of those places with coffee or sugar, which was damaged on board, and the noxious effluvia, or air arising therefrom, remaining: if the ship be again fitted for sea, without being perfectly cleaned and well ventilated, diseases, will certainly ensue, and particularly if sailing towards tropical climates. Another thing, too commonly done, is washing the shingle or gravel ballast, while ships are in dock; the ballast remains wet, and, of course, must decay the bottom of the ship, and not only that, but will also produce foul air, which is highly pernicious to the health of the crew, and destructive to the cargo.

|

|

22 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

I would therefore particularly advise, on no account to wash the ballast in the hold of a ship, unless sufficient time can be given to have it perfectly dried before the cargo is taken in. Where fires are not permitted while ships are in dock, the best mode of airing and drying a vessel below is by large wind-sails, which should be made of a topmast studding-sail, the head of it confined, or brought to a yard, and three parts sewn together from the foot; the part to which the yard is fixed must be hoisted up, so that the wind can blow freely through it, and the other let down in the ship’s hold, or places requisite to be ventilated and dried; braces being fastened to the yard to trim it as the wind changes. A wind-sail should be put down every hatchway of the vessel.

"The bread-room should be whitewashed previous to storing the bread, and a wind-sail frequently put in, as nothing tends more to its preservation than airing it. The habitation of the crew should be washed, but never while they are obliged to be in it; and it ought always to be scraped, or dry-cleaned with rubbing-stones and sand. The between-decks, and the habitation of the crew, as well as the hold, whenever it is cleaned out, should be whitewashed with quick-lime; this may be done at little expense, and is not only a preventive against diseases, but also preserves the timber and planks. If the ship leaks or admits water, it should never remain longer than twelve hours without being pumped out, as the closeness of the well not only rots the pump, but occasions unwholesome effluvia, or bad air; indeed, if the water has been there a considerable time, the air becomes so bad that no one can go down without risking life.

"The ship being well ventilated and ready, and the cargo received on board, the men are generally shipped with scarcely any other clothing than what they have on; this may have been purchased from houses or cellars at which they have lodged, where the inhabitants have perhaps been afflicted with the typhus fever, or other infectious diseases; for this reason, it would be always advisable, if possible for the men’s clothing to be well

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

23 |

fumigated and aired previous to coming on board. The bedding and blankets should be aired, and the former composed of horsehair– wool or flocks being more likely to harbour infection, and not so easily cleaned. It would be preferable for the men to sleep in hammocks instead of bed-places, the latter being seldom cleaned; and often, when one of the crew dies of an infectious disease, another occupies his place, not thinking any harm can arise."

Though the amount of care bestowed on the internal arrangements and cleanliness of merchant-ships has greatly increased, and the standard of health has consequently improved, of late years, yet there is undoubtedly room for further improvement, especially in the matter of ventilation. Too often, even during the finest weather, the ordinary means of sending plenty of fresh air through the between-decks and hold are neglected. This will never be the case in a well-ordered ship: on the contrary, in fine weather, every means will be taken to make the atmosphere of the interior of the ship as nearly as possible like the open air; and in bad weather a clear fire in a hanging grate, or chauffer, will be frequently shifted about between decks, lowered into the pump-well, and moved into any position where it can safely be placed, to dry and ventilate the ship.

It will be desirable to swab out all the sleeping-places for the crew, deck-houses, galleys, cabins, &c., once in every four or five days, with water in which Carbolic Acid has been mixed, in the proportion of a tablespoonful to each bucket. – (See page 2.) Condy’s Disinfecting Fluid may be used instead, in the proportion mentioned in the directions on the cases. Whenever any contagious disease has broken out on board, or when you have reason to fear infection from any source, let the same process be gone through every day, and let the mixture be used for washing the men’s clothes, &c., but do not increase the quantity of acid in the water, or the metal-work of the ship may be damaged. Let the hold be cleaned out as often as is practicable with the same mixture; and be particularly careful to have all foul places, waterclosets, &c., constantly purified with it. When Carbolic Acid cannot be obtained, Chloride of Lime may be used to sweeten the

|

|

24 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

air and destroy infection. A pan or flat dish containing a handful of it moistened with water may be placed where required; a little vinegar poured on it now and then will renew its efficacy.

Let the duty of carrying out these necessary measures, and a sufficient supply of the material, be entrusted to some one person on board who shall be responsible for its being done regularly.

In the absence of any better means of purifying the ship, let it be fumigated with tar-barrel staves or tarred rope, burnt in iron pots or in a stove: the hatchways being all shut close and covered with tarpauling. Or let sulphur be burnt in a mess tin with a few dry shavings mixed with it, float this tin in a bucket half full of water. See that every opening is tightly closed, and after careful examination that no person or animal is left inside, sprinkle a small quantity of methylated spirit over the sulphur and set fire to it. Keep the place closed for at least four hours. And afterwards have it thoroughly ventilated with fresh air and washed out. Blankets, woollen clothing, bedding, &c., can be fumigated in this way by hanging them on lines before lighting the sulphur. The amount of sulphur required is one pound for every 1,000 cubic feet of space.

The beds, bedding, and clothing used by Small Pox or Cholera patients should be destroyed, thrown overboard at sea, or burned in harbour. In modern steamers, with steam of over 300° Fahr., good use can be made of steam for disinfection by simply leading a length of steam hose from the exhaust of fore-winch into forecastle, closing the door and turning the steam on. In a very short time every living thing (bugs, cockroaches, &c.) is destroyed.

FOOD, CLOTHING, AND TEMPERATURE.

Nothing tends more to make men unable to resist the attacks of disease than insufficient or improper food. Be sure therefore to use every means at your disposal for procuring wholesome and varied food for the crew. Shipowners and captains are advised to read the circular recently issued by the Board of Trade on the subject, written by Mr. Thomas Gray, "Department Paper" No. 75, in which the following scale is suggested: –

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

25 |

| | Biscuit | Flour | Beef | Pork | Pre-served Meat | Peas | Pre-seerved Pota-toes | Pre-served Car-rots | Butter | Oatmeal | Rice | Marma-lade | Sugar | Raisins | Molasses | Suet | Pickles | Tea | Coffee |

| | "oz.

| oz.

| lb. | oz.

| oz. | oz.

| oz. | oz. | oz. | oz. | oz. | | oz. | | | | | oz. | oz. |

| Sunday. | 12 | 8 | | | 12 | 1/3 | | 8 | 2 | | | | 2 | | | | | 1/8 | 1 |

| Monday. | 12 | | 1 | | | | 2 | | | 4 | | | 2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 4 | 4 | 1/8 | 1 |

| Tuesday. | 12 | 8 | | | 12 | | | 8 | | | | | 2 | lb. | pint | oz. | oz. | 1/8 | 1 |

| Wednesday. | 12 | 8 | | 12 | | 1/3 | 2 | | 2 | | 4 | | 2 | per | per | per | per | 1/8 | 1 |

| Thursday. | 12 | | | | 12 | | | 8 | | 4 | | | 2 | week | week | week | week | 1/8 | 1 |

| Friday. | 12 | 8 | 1 | | | | 2 | | | | | | 2 | | | | | 1/8 | 1 |

| Saturday. | 12 | 8 | | 12 | | 1/3 | 2 | | | | 4 | | 2 | | | | | 1/8 | 1 |

| 1 Man per week | 5.4 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1 pt. | 8 oz. | 1.8 | 6 oz. | 8 oz. | 8 oz. | 1 lb. | 14 oz. | 8 oz. | 1/2 pt. | 4 oz. | 4 oz. | 1 oz. | 7 oz. |

Substitutes.

Fresh meat to be given instead of salt, and preserved as long as possible after leaving Port.

Fresh potatoes, carrots, &c., 3-1/2 lbs. Per week, instead of preserved vegetables, as long as they last.

Oatmeal may be substituted for rice in cold weather, and vice versa in hot weather.

Preserved onions may be substituted for preserved carrots.

|

|

26 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

Fresh vegetables – especially fresh potatoes – ripe fruit, and good pickles, in moderation, are great luxuries and at the same time most wholesome medicines to those who have been a long time without them. In all cases men should not be made to hurry their meals, and should not take any violent exercise immediately after them. Even in hot climates the men should have a good supply of warm woollen clothing. The hours just before sunrise are cold enough to require the warmest garments. Flannel should be worn next the skin in all climates. Sudden changes of temperature are always hazardous. They are often the starting points of Rheumatism, Ague, or Diarrhoea. It is always better to be too warm than too cold. All clothing should be carefully kept clean and dry; and wet garments should be exchanged for dry as soon as the nature of the service permits it. Getting wet through seldom hurts anybody; but sitting in wet clothes until you are chilled is a dangerous habit. The men should not be allowed to sleep on deck unless under a stout awning.

There is a common belief that bathing or washing in cold water when the body is very hot is unsafe. But the fact is, provided the man is not out of breath, nor in a state of great excitement, the hotter the body is when it is plunged into cold water the better, both as regards safety and refreshing effect. In all cases, however, as soon as a man begins to feel chilly, it is time for him to discontinue his bath.

A similar prejudice exists against drinking cold fluids when the body is heated. It is quite true that if a man drinks an enormous quantity of cold fluid when in that state he may make himself very ill, and even endanger his life: but so long as he takes a small amount, and continues the exercise which heated him so as to keep his body warm, there is no danger.

In general terms it may be said that anything which rapidly lowers the temperature of the body and induces a painful feeling of chilliness, is injurious, if it continues any length of time.

It is a very bad practice to maintain a hot and stifling atmosphere in the forecastle and cabins: it makes men liable to colds

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

27 |

and disorders of the lungs and throat. A moderate temperature with good ventilation is the most comfortable as well as the healthiest.

The men’s bedding as well as their clothing should be kept carefully clean and dry, and should be brought on deck every day in fine weather. Finally, a ration of hot coffee should be served to the men before turning out in the morning.

WATER.

A plentiful supply of pure water is of the first importance. Many diseases are produced by impure water, e.g., Diarrhoea, Dysentery, Cholera, and Typhoid Fever. Water should be kept in iron tanks, which should be frequently cleansed and cement-washed – in fact this should always be done before taking in a fresh supply. Pure water should be bright and tasteless, and without smell. If muddy, add a little alum, about 1 ounce to 100 gallons.

If there is a suspicion that the water is not good, add a few drops of Condy’s Fluid – if pure and good, a faint pink colour will be produced. If foul, the colour will be quickly destroyed. When this is the case all the water should be filtered before using, and if it still remains foul it should be boiled. Ships at sea on long voyages should carefully collect all the rain-water possible, as it is the purest and best that can be obtained. There are many ports abroad where the water is admittedly bad, such as Batavia, Savannah-la-Mer, Parahibo, ports in Dutch Guiana, Hong Kong, Foo-choo-Foo, Bombay, and Kurrachee. Water from all these ports should be filtered and boiled.

Note. – Wherever disease is epidemic, drinking-water should be boiled and filtered.

|

|

28 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

USE OP SPIRITUOUS LIQUORS.

Probably it will be a long time before people will believe that when plenty of good water is to be had, and men are in good health, they can do perfectly well without spirituous liquors of any kind. Yet this is undoubtedly true, as many instances have shown. For example, during the American War, large armies engaged on most trying service were kept without spirits with great advantage to themselves: and in the American Navy a similar practice prevails. It is a mistake to suppose that spirits can fortify the body against cold. The experience of Arctic voyagers is entirely in favour of the use of coffee, strong broth, or tea for this purpose. Spirits may be, and often are, necessary when a man has been depressed by long exposure to cold; but their effect is not lasting enough to fortify him beforehand. In fact the men will gladly take coffee, &c., instead of grog in such cases, as they feel the cold so much less on these than on spirits. The evils of drunkenness on board ship are so obvious that it is hardly necessary to do more than refer the reader to the articles in this book on "Delirium Tremens," "Apparent Death," and "Liver Diseases." In tropical and unhealthy climates it will always be the drunkards who are in the greatest danger from malarious influences. A judicious captain will always take pains to enforce his men’s attention to this fact.

PREVENTION OF CONTAGIOUS DISEASES.

When a ship arrives off a port where such diseases as Yellow Fever, Ague, or Typhus are known to be raging, the crew should have as little communication as possible with the shore. No man should on any account be allowed to sleep on shore. A dose of from three to five grains of Quinine should be served out to all hands early in the morning, as soon as they turn out. Those necessarily employed on shore in discharging the cargo, watering the ship, &c., should have a double dose. A cup of strong coffee served out to the men every morning will also be of use.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

29 |

An anchorage should be selected as far off the land as possible, and away from the neighbourhood of marshes. The land-breeze coming over such spots is highly dangerous. The difference of a hundred yards in an anchorage has often made a most marked alteration in the health of a ship’s crew, either in increasing the number of deaths, or favouring recovery.

In hot climates awnings over the ship and boats will be of great advantage to health, and wind-sails should be constantly used. The men should never be kept at work under a scorching mid-day sun, during those hours in which the natives of tropical countries seek shelter, nor during heavy rains. Nor should they be exposed, if it can be avoided, in the hour just preceding sunrise, nor in that just after sunset.Neglect of these precautions is sure to be followed by more or less sickness among the crew.

Eating unripe or over-ripe fruit, or an inordinate quantity of ripe fruit, in places where diarrhoea is prevalent, is a common source of disease, and should not be permitted. The danger of drunkenness under the same circumstances has been already insisted on.

When a contagious or spreading disease has already made its appearance on board, the utmost care should be taken. The men should be instructed to come aft for treatment without delay, as soon as the first symptoms shew themselves. The sick must be separated from the rest of the crew, and their quarters kept scrupulously clean and sweet with Carbolic Acid, Condy’s Fluid, or Chloride of Lime, as directed at page 23. All discharges from their bodies, all foul dressings, &c., must be thrown overboard immediately, and the utensils purified. Their usual clothing should be put as soon as possible into boiling water, and as little apparel and lumber as possible should be kept about them. When the sun shines, and in dry weather, all their clothing, bedding, and belongings should be exposed to the air on deck or in the rigging. The deck should be sprinkled with vinegar, and the habitation of the crew well white-washed and kept perfectly dry.

Above all things the captain will do well to remember that under such circumstances the safety of the crew depends in a very

|

|

30 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

great degree upon his own vigilance and promptitude. He must not allow the crew to become negligent or discouraged. The man who lives in fear of the disease is ready to meet it half way. Some cheerful employment should if possible be constantly provided for the men to prevent them from brooding over the disease, as men who are a little out of health are certain to do if they have no other occupation. And men will face this, as they will other dangers, better or worse according to the example set them by their officers.

GENERAL RULES FOR TREATMENT OF THE SICK.

The sick bay or cabin where the patient lies should be kept sweet and airy. There should never be any close smell in it. No difficulty need be found in effecting this in any but very bad weather. The air should be always kept moving slightly, and a moderate amount of light should be admitted if possible. All unnecessary disturbance to the sick man should be avoided, and he should not be made to talk too much. His face, hands, and feet should be often washed with warm water and soap, and if he can bear it the body may be now and then sponged with weak vinegar and water and well dried. The mouth should be rinsed out with vinegar and water. The hair should be cut rather short, and frequently combed out. The body-clothing should be kept clean and dry, and often changed.

Let some one person be responsible for giving him food and medicines at the proper times, and let no one else interfere. Especially let no one give him any spirituous liquors without instructions.

When a man has been long confined to his berth, great care must be taken that the back and hips are kept clean and dry. If any place looks red or tender, dab it twice a day with brandy or some other spirit, and arrange pillars or pads so as to support the body and take the weight off the tender parts. Such places are liable to break, and become what are called "bedsores," and to be very painful and exhausting to the patient. If the skin comes off apply Basilicon Ointment (No. 31) spread on soft rag.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

31 |

The sick person should be treated as a child. The patience of those who attend on him is often tried to the utmost by his petulance and irritability: but let every man remember that it may at some time be his own lot to change places with the sick man, and to have no more power of self-control than he has.

In all cases, remember the importance of losing no time. Both accidents and diseases which might if taken in hand at once have been easily cured, frequently injure a man for life if neglected.

—————

ACCIDENTS.

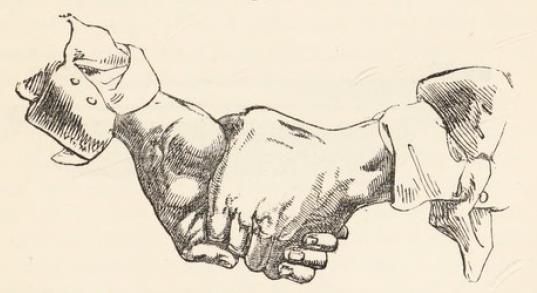

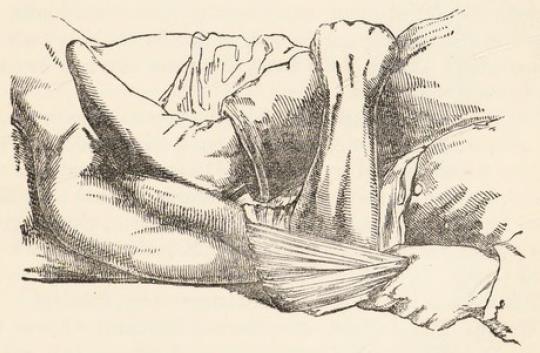

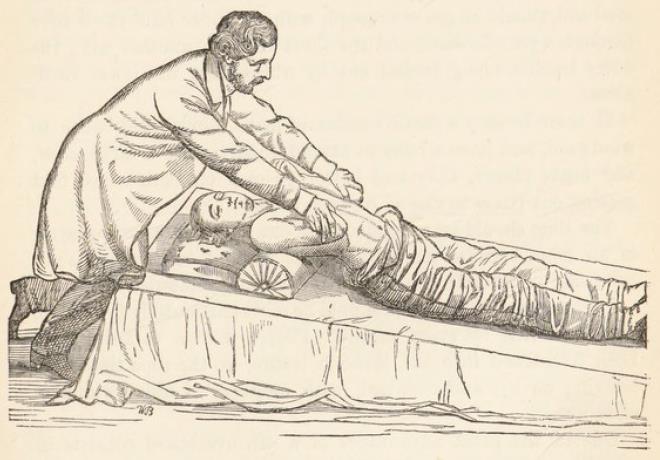

When a man has fallen from a height, or been otherwise injured, ascertain at once, if possible, what damage has been done. If a bone has been clearly broken, or a wound inflicted, adopt the treatment described below without delay. But if the nature of the injury is not at once clear, loosen his clothing, especially about the neck, put him on a stretcher, or if that cannot be done, let two men join hands, as shewn in Fig. 1, each man’s right

Fig. 1.

hand grasping the others left, and lift him gently, putting one pair of hands under his back and the other under his knees. Let him be taken to a convenient place, near his berth or cot if possible, and take off his clothes, cutting them off rather than pulling them from the neighbourhood of the injured part. If he be stunned by the blow, and lies pale and faint without moving or speaking,

|

|

32 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

do not be in too great a hurry to interfere. Mr. Guthrie, the late well-known army surgeon, says of such a case, "It is useless to open the patient’s veins, for they cannot bleed until he begins to recover, and then the loss of blood would probably kill him. It is as improper to put strong drinks into his mouth, for he cannot swallow; and if he should be so far recovered as to make the attempt, they might probably enter the larynx (that is, the windpipe , and destroy him. If he be made to inhale strong stimulating salts, they will probably give rise to inflammation of the nose and throat, to his subsequent great distress."

If the skull be not broken, and no blood-vessel burst inwardly, he will soon come round: if otherwise, there is little to be done. Put him to bed, cut his hair short, bathe his head with cold water, and wait for his coming to. In the meantime, if there is manifestly any bone broken or out of joint, you may adopt the means described under the different heads in this work.

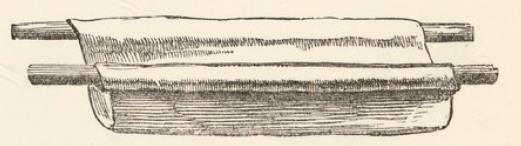

A litter may be easily made with a couple of oars or poles and a blanket, as shown in Fig.2. If the blanket is long enough, it need only be folded; if not, it must be fastened in some way.

Fig.2.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

33 |

WOUNDS.

—————

HOW TO STOP BLEEDING.

The first thing to be done in wounds of all kinds is to prevent further loss of blood, and this is sometimes a matter of great difficulty. The first point to be settled is whether any artery is wounded or not. The blood from an artery is of a bright scarlet colour, and is pumped out in jerks by each beat of the heart. If the cut end of the artery is actually exposed, the blood may be seen to spring from it in a jet, which is sometimes thrown to the distance of two or three feet. The reason of this is that the arteries are tubes penetrating the whole of the body, conveying the blood fresh from the heart to all the limbs and organs; and every beat of the heart is like the stroke of a force-pump. It is this stroke, felt in the artery, which forms the pulse at the wrist and elsewhere.

The veins, on the other hand, convey blood back from the limbs to the heart, and the colour of this blood is dark crimson, with even a bluish tinge. This may be seen in the veins which lie immediately under the skin in fair persons. The blood in the veins flows in an even stream, without jerking.

Therefore, if the blood from a wound is scarlet, and springs or wells up in jerks, you may be sure that an artery is wounded.

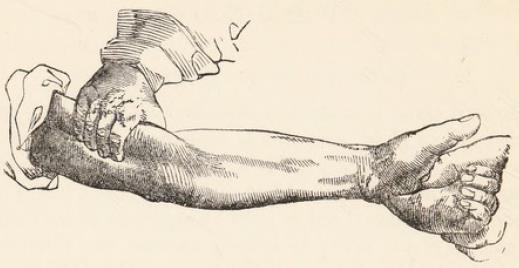

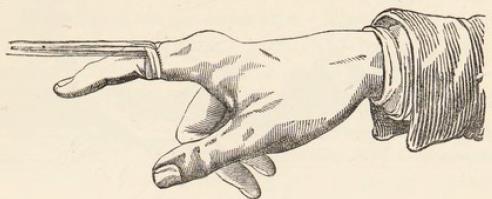

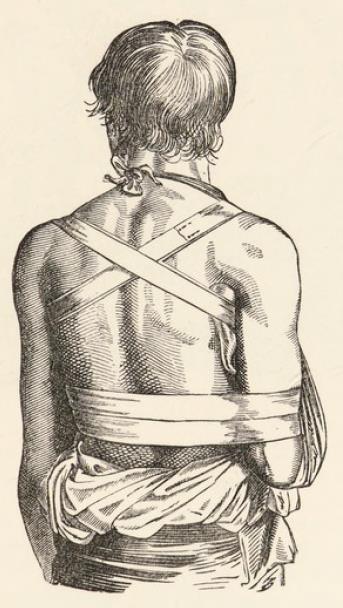

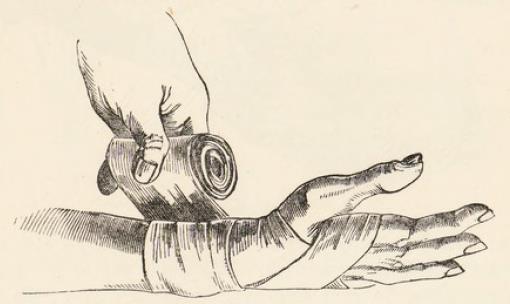

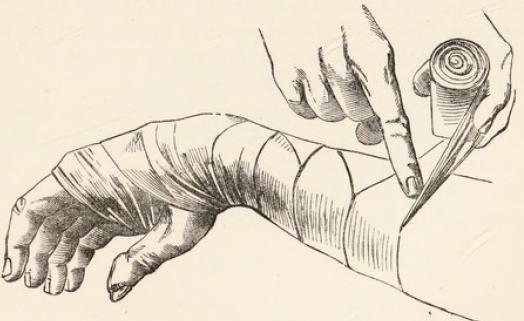

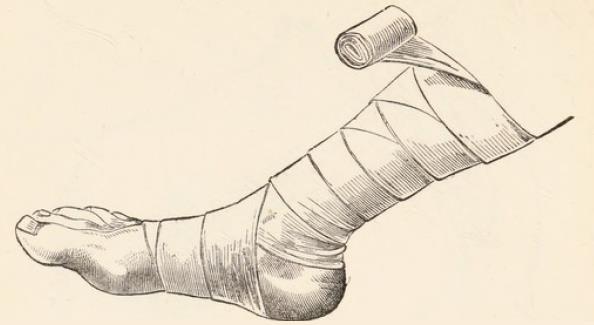

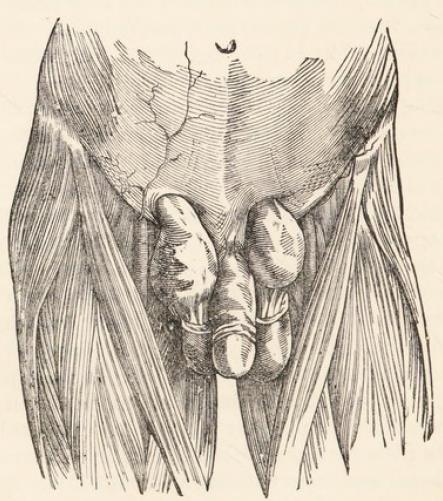

If the wound is in one of the limbs, the bleeding may be controlled by compressing the artery at some point higher up the limb. In the case of a wound of the hand or lower arm, the artery should be pressed firmly against the bone by the fingers of one hand, about the middle of the inner side of the upper arm, as shown in the drawing (Fig.3). For a wound of the leg or thigh, the main artery is most easily compressed on the inner side of the front of the thigh near its upper end, on that part of the groin where a watch lies in a fob. Another mode of compression is by laying a small roll of bandage, or a short piece of stick, over the artery, and binding it tightly to the limb with a hand-

|

|

34 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

Fig.3.

Fig.4.

Fig.4.

kerchief or piece of linen; or by tying a large, hard knot in the handkerchief, and tying it round the limb, taking care to place the knot over the artery. For wounds of the foot or lower part of the leg the handkerchief may be tied round the knee, with the large knot in the hollow of the ham. For wounds of the hand or upper arm the knot or pad should be placed as shewn in Fig.4, on the same spot on which the fingers are pressing in Fig.3. The handkerchief or bandage may be further tightened by having a stick twisted into it (Fig.4). The proper instrument for the

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

35 |

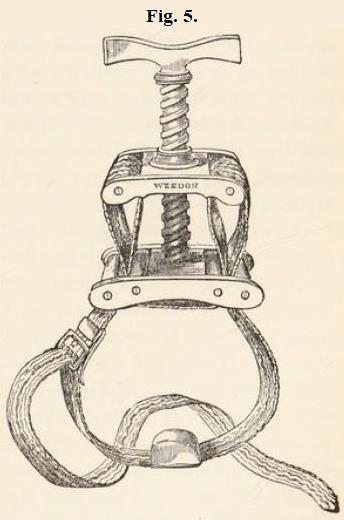

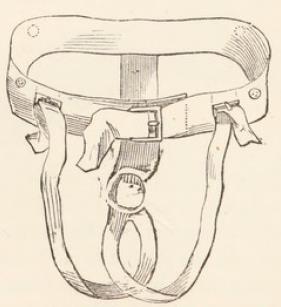

purpose is the Tourniquet (Fig.5), the pad of which is to be placed over the artery, and the strap buckled round the limb, and tightened by means of the screw. Or Esmarch’s Tourniquet (which is simply an elastic tube about 24 inches long, and as thick as the little finger, having a hook fixed to the ends, and which ought now to be in every medicine chest) may be applied by putting it on the stretch, and bound round the limb above the wound, and fixing the hooks. The advantage of Esmarch’s Tourniquet over the older screw Tourniquet is, that it is easily and quickly applied, and requires no

knowledge of the position of the arteries. In applying anything of this kind which goes quite round the limb, it is necessary to draw it tight quickly, so as to stop the beating of the artery at once; because if the veins of the limb are compressed while the artery is not, the blood contained in them is prevented from returning to the heart, and the bleeding from the wound is increased. But at the same time that this is being done, the wound itself should be firmly grasped or pressed as soon as possible, as shewn in Fig.3, which represents a wound in the hand. In all but very severe cases this will usually suffice to control the bleeding for a time, without the use of the Tourniquet or other means. If the wound be in the hand or arm, the arm should be held up: if in the foot or leg, the patient should lie down, and the leg should be raised.

knowledge of the position of the arteries. In applying anything of this kind which goes quite round the limb, it is necessary to draw it tight quickly, so as to stop the beating of the artery at once; because if the veins of the limb are compressed while the artery is not, the blood contained in them is prevented from returning to the heart, and the bleeding from the wound is increased. But at the same time that this is being done, the wound itself should be firmly grasped or pressed as soon as possible, as shewn in Fig.3, which represents a wound in the hand. In all but very severe cases this will usually suffice to control the bleeding for a time, without the use of the Tourniquet or other means. If the wound be in the hand or arm, the arm should be held up: if in the foot or leg, the patient should lie down, and the leg should be raised.

For permanently stopping the bleeding, one of two modes may>

|

|

15 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

be employed. The first is by plugging the wound. This requires to be done very carefully, but any one may succeed in it by attending to the following instructions. First find out the bleeding point. This is to be done by gently clearing the wound of clotted blood and exploring it with the fingers. The place from which the chief stream of blood issues may then be either seen or felt. If the bleeding is stopped for the time by the Tourniquet, or pressure with the hand on the artery, the pressure may be relaxed for an instant, in order to ascertain the bleeding spot, and then immediately renewed. Place a finger firmly on the spot, and with it press down a small plug of folded lint, less than an inch square, on the very point from which the blood issues. On the top of that put one slightly larger, and add another and another, pressing them down firmly until the wound is filled up to a little above the surface. Then put on the top of the pile a thick piece of cork or a piece of wood, and secure the whole with a bandage or strong strips of plaster, taking care that the plug really presses down into the wound at the very spot required. The lint used for the plugs should be dipped in Friar’s Balsam, if any is at hand.

The other mode of stopping bleeding from an artery is by tying a piece of silk or thread tightly round the artery above the wounded point. This requires considerable coolness and skill, but it may be accomplished by any handy and resolute man, especially if he has seen it done before. The way of proceeding is as follows: – Having got the bleeding under control by means of the Tourniquet, or by compressing the main artery of the limb (if the wound is in one of the limbs), remove the clots gently from the wound with the help of a sponge, and try to find the spot from which the scarlet blood proceeds. Then with a forceps or pair of tweezers seize the bleeding point, raise it very slightly above the surrounding surface, and tie a piece of strong silk or waxed white thread tightly round it. Then let go with the forceps, and see whether the bleeding from that point is stopped. If it is not, you have failed to secure the vessel, and must try again. If the cut ends of the artery (which appears as a whitish elastic

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

37 |

tube, from the size of a goose-quill downwards) can be seen, there will be no difficulty in seizing them with tweezers or drawing them slightly out with a hook or needle, so as to be able to tie them; but this will not often be the case. If a wound can be seen in the side of an artery which is not quite cut through, a needle can be passed behind it to lift it up, and a thread tied round the artery, both above and below the wound. When the artery is quite cut through, both ends must be tied. But this will generally be a work of difficulty, because the artery, when cut, shrinks back among the flesh. One end of each thread used for tying an artery should be cut off near the knot, and the other end left hanging out of one corner of the wound. The threads will come away of themselves in from nine to fifteen days. They should not be pulled unless they are quite loose.

The "reef-knot " is the best to use in tying arteries. Great care must be taken not to include any nerves in the knot. A nerve is a white cord which does not beat like an artery.

The mode of tying arteries has been described in order that if there should be any man on board capable of doing it, this book may serve as a guide to him. But if you have not sufficient confidence to try it, it will be better to rely on plugging the wound in the way before described; always remembering that unless the deepest part of the plug bears exactly on the bleeding point, it will be of no use.

If all other means fail, rather than let a man bleed to death, use that old, and in appearance terrible remedy, the hot iron. Let it be at a black-red heat, and apply the point of it only to the exact place from which the blood issues. The remedy is really not so formidable as it seems. Bandage as before directed.

As soon as by one or other of these means the bleeding has been stopped, let the patient be placed gently in his bunk or cot, in as easy a position as possible, and with the wounded part raised (if this can be done) and very lightly covered. The Tourniquet or handkerchief which has been bound tightly round the limb to control the bleeding should not be taken off, but should be allowed to lie loosely in its place, in order that it may be tightened imme-

|

|

38 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

diately if the bleeding should return. It is not safe to keep it tight for more than ten or twelve hours at the utmost, for fear of making the limb swell or mortify. The patient should not be left alone for three or four days, because startings of the limb, or movements of the body may throw the dressing or plugs out of place, and cause the bleeding to return at a moment’s notice. If this after-bleeding should occur, the Tourniquet or handkerchief must be tightened, the dressings removed, and the wound plugged afresh.

If ice is procurable, let a small bladder filled with it be laid ¦over the wound. If not, let rags wet with cold water be laid over it, and changed frequently, to keep the part as cool as possible.

While you are endeavouring to stop the bleeding, you should gently cleanse the wound from dirt, and any substances that may have found their way into it, with a sponge and cold water; but when the bleeding has ceased you should allow the dressings to remain undisturbed until they are loosened by the formation of matter, which will have occurred by the fourth day. Then remove what is loose carefully, taking care not to drag anything away by force, and put clean lint or soft rag instead of it. Afterwards treat the wound as you would any other, according to the directions given below.

In Bleeding from Veins, the blood is dark and flows in an even stream. It is easily stopped by the pressure of a pad and bandage applied immediately below the wound. If applied above the wound, the bleeding will be increased.

—————

DIFFERENT KINDS OF WOUNDS.

Wounds are either cut or torn: and those which are torn are attended with various degrees of injury to the surrounding parts. Under the head of torn wounds we include those made by blunt instruments, bayonet wounds, gun-shot wounds, the bites of animals, and the like.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

39 |

Simple cuts, even if very extensive, are the most easily recovered from; and those which run in the direction of the length of the limb are the most favourable. Such wounds, if no considerable artery has been injured, and if the patient is healthy, may be very easily repaired in the following way: – First, remove all dirt and clotted blood with a sponge and cold water. Then, if the cut be of moderate size and in a convenient place, bring its edges carefully together, without using force, and keep them in position with long strips of adhesive plaster. If the cut be on a limb, the strips should reach half way round the limb. The plaster should be slightly warmed, and should be pressed on the skin for a minute or two to make it hold firmly. Small spaces, about a straw’s breadth, should be left between the strips where they cross the wound; and moisture oozing from the wound should be dried. Then lay a small piece of lint, thinly spread with fresh Simple Ointment (No. 33), or dusted over with Iodoform (No. 63) which need not be renewed for two days, or with Carbolic Oil (see Receipt No. 14), along the track of the wound, and over it one or two folds of soft rag, and bind up the limb lightly with a bandage, extending some distance above and below the cut. (See the article below on Bandaging.)

If the cut is large, and its edges cannot be brought together satisfactorily by plaster, one or more stitches must be inserted. This will be required most often in cuts on the face, neck, or parts of the body where the plaster cannot be readily applied; but it will be better to do without the stitches whenever it is possible. Stitches should not be used at all in wounds of the scalp.

The stitching may be done in two ways. A sharp straight or curved needle may be

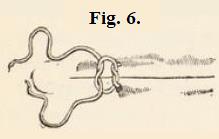

threaded with strong white waxed thread or white silk, and thrust through the skin at about a third of an inch from the outside edge of the cut until the point appears in the wound. The edges should now be brought together, and the needle pushed on so as to come out at about the same distance on the opposite side of the cut. The thread is now drawn through, and the

threaded with strong white waxed thread or white silk, and thrust through the skin at about a third of an inch from the outside edge of the cut until the point appears in the wound. The edges should now be brought together, and the needle pushed on so as to come out at about the same distance on the opposite side of the cut. The thread is now drawn through, and the

|

|

40 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

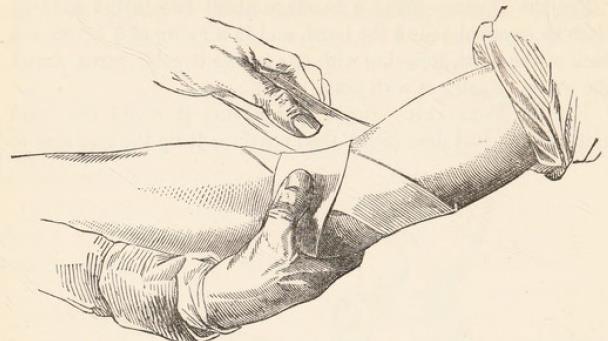

ends tied firmly with a reef-knot, so as to hold the edges together gently, without any straining (Fig.6). Then apply strips of plaster between the stitches, and proceed as before.

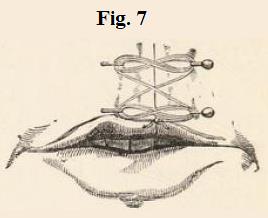

The other method is to thrust a straight pin or needle (in Fig.7) through both sides of the wound as before, but a little more deeply, and to whip a thread or silk figure-of-8-ways under both ends of the needle, while the edges of the wound are held gently together. The point of the pin may now be cut off with a pair of pliers. One advantage of this plan is that the thread is easily unwound and the pin drawn out when required.

The stitches may be about three-quarters of an inch apart. They should be removed in from three to six days, or sooner if the wound becomes greatly inflamed. When the edges of a wound are hard, red, and projecting, and the parts around are painful, hot, and throbbing, inflammation may be known to have begun. All attempts to hold the edges together must now be abandoned, and hot linseed-meal poultices must be applied. The poultices must be changed every four or flve hours, or oftener, according to the quantity of discharge coming from the wound. When the inflammation has abated, and the surface of the flesh looks clean and red, water-dressings may be applied instead of the poultices, until the cavity has become filled up with new flesh, over which skin will gradually form.

If a wound that has been stitched, however, does not inflame, it should be allowed to remain as still and undisturbed as possible until the fourth day, when the bandage may be unfolded, and the dressings changed. If the dressings stick together they should be softened and loosened with a sponge and warm water. They may be afterwards changed every day, the rags applied being moistened with weak carbolic acid lotion (No. 9). When the stitches have become loose, they may be removed by cutting the threads.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

41 |

The patient’s bowels should be kept moderately open with Castor Oil or other mild aperients. So long as there is any danger of inflammation he should take no solid food, nor spirituous liquors of any kind, but live on light broth, sago, rice, and similar kinds of mild diet. It often happens that a man in good health receives a wound, and feels so little inconvenience from it that he makes no change in his manner of living; but after two or three days he is sure to find out his mistake. The time is always saved, and pain avoided, by attending to a wound at once.

In the case of a cut on the Scalp, the hair should be cut off or shaved as close as possible to the extent of an inch or two in every direction round the wound, in order to allow the plaster to stick, and to promote cleanliness; and cold wet cloths should be applied to the head. All wounds of the head should be carefully attended to, on account of their liability to inflammation, which may be attended with dangerous consequences. In such cases the man must be put on the lowest diet, kept quiet, and the Soothing Mixture (see Receipt No.5) given regularly.

TORN WOUNDS.

These may be caused by any more or less blunt instrument, such as a nail, a bayonet, a sword’s point, or the tooth of an animal; or by missiles of any kind, such as stones, bullets, fragments of shell, or cannon-shot.

A deep wound of this kind, even though the hole made is a small one, is always more serious than a cut, however extensive. The reason is that the structures through which the weapon passes are crushed in its passage, and must become inflamed and discharge themselves through the narrow hole left open. Therefore it is sometimes desirable, when the wound is not near any vital part, to enlarge its opening both ways with a knife, so as to convert it as nearly as possible into a simple cut. But this must be done with considerable caution. In the case of gunshot wounds it is better not to attempt it.

If a rent or stab of any kind has penetrated the Chest or Belly, the patient will be in great danger. In wounds of the chest, if

|

|

42 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

the lungs are penetrated, which will be known by froth or air escaping from the wound, he must be kept perfectly still, with the injured side downwards, and fed on the lowest diet – weak broth and toast and water – until the breathing becomes easy. If he be a robust man, and the breathing be very much oppressed, with swelling of the veins of the head and neck, it may be necessary to take blood from the arm. He may have bled internally, though very little may have escaped from the wound; this may be suspected to be the case if he becomes very pale and faint without apparent cause. If he appears to be sinking – but not otherwise – a very little wine or brandy in water may be given him. But the main object is to keep his whole body in as quiet a state as possible, so as to avoid anything that may excite a return of the bleeding. His bowels must be kept moderately open; and for this purpose injections are best, if they can be given without disturbing him. He may drink small quantities of iced water, or suck a lump of ice. The wound should be covered with lint kept wet with cold water, so as to exclude the air.

In wounds of the belly, if the bowels protrude they must be gently put back, and the edges of the wound kept together by one or two stitches if necessary, care being taken to allow space for the escape of fluids from the wounds. The patient must be placed with the wounded side downwards, to allow discharges to run off easily. The treatment afterwards must be directed to the object of keeping him perfectly quiet, and avoiding inflammation. If great pain and vomiting come on, and he be a robust man, blood must be taken from the arm. If leeches can be procured, a dozen should be placed over the belly. A piece of flannel wrung out of hot water should be laid over the belly (not over the wound); and Opium is the only medicine that must be given. One pill (No. 39) every three or four hours until he becomes drowsy; afterwards, when the effect of them has passed off, one, two, or three in the day, according to the amount of pain. The bowels will be very costive, but no attempt must be made to get them open. No solid food of any kind must be given. Iced water, or a lump of ice to suck, toast and water, or cold broth by spoonfuls, must

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

43 |

be the only nourishment. The wound should be covered with lint kept wet with cold water.

If a wound of any kind penetrates a Joint, there is great risk of the patient’s losing the use of the joint, if not his life. Indeed it has been generally supposed that a bullet-wound of the knee-joint is a fatal injury: but many cases occurred in the late American War which proved the contrary: one case in particular may be mentioned, in which an officer was shot through both knees with the same bullet, and yet recovered with fair use of his legs. Therefore you need not despair of cases of even severe wounds of joints, whether they are clean-cut or torn. The clear gummy fluid which fills the interior of the joint may be seen escaping from the wound, and will inform you at once if a joint has been opened. The ordinary consequences are severe inflammation and swelling, with acute pain, and a copious and exhausting discharge, which often wears the patient out. The first object must be to keep the joint perfectly immovable for about a month or longer; this is accomplished by laying the limb on a splint, and securing it with a carefully adjusted bandage. The splint must extend nearly the whole length of the limb, and the wound itself should be left uncovered by the bandage, so that it can be dressed without loosening the splint. If the knee is wounded, the splint should be straight, and placed behind the limb: if the elbow, the splint should be shaped like a capital  . But with the angle widened a little, (thus . But with the angle widened a little, (thus  ), and should be placed on the inner side of the limb. The joint is liable to become permanently stiff in a position in which it is placed, so that it is important that it should be placed in the most useful position. The next object is to close the wound if possible, and apply Iodoform (No. 63) or Carbolic Oil (see Receipt No. 14) on lint, and dressed carefully and regularly. ), and should be placed on the inner side of the limb. The joint is liable to become permanently stiff in a position in which it is placed, so that it is important that it should be placed in the most useful position. The next object is to close the wound if possible, and apply Iodoform (No. 63) or Carbolic Oil (see Receipt No. 14) on lint, and dressed carefully and regularly.

If the wrist-joint is wounded, the whole hand and lower arm must be bandaged to a flat splint. Wounds of the ankle-joint must be treated with an  shaped splint fitted to the inner side of the leg and foot. The splints must be padded, as directed under the head of Fractures. shaped splint fitted to the inner side of the leg and foot. The splints must be padded, as directed under the head of Fractures.

|

|

44 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

Gunshot Wounds, in which the bullet has passed out of the body, differ from those caused by other blunt instruments only in the amount of damage done to the structures through which the ball passes. If the bullet remains in the body it is usually an additional source of danger – though there are many instances of men carrying bullets about in them for forty or fifty years without serious inconvenience.

The ball should always be extracted if possible; but this is usually a task which requires some surgical skill. If, however, you find that you are able to lay hold of it easily with any instrument, you may make the attempt; or if it lies immediately under the skin, you may cut down upon it very cautiously; but it is often no easy matter to get out a bullet which seems to lie in your grasp.

The effects of a conical rifle-ball are much more serious than those of a round bullet. The former smashes bones, while the latter frequently glances off them, or only slightly injures them. The former generally passes straight through wherever it strikes; the latter often runs round the body under the skin, or buries itself at a distance without doing much damage. Injuries to bones by gunshots must be treated like other Compound Fractures, as described under that head.

The hole by which a ball passes out is always larger than that by which it went in.

If a ball or any other weapon enters the skull, death is almost certainly instantaneous.

When a ball passes through fleshy parts without breaking a bone, the chief danger is that some large blood-vessel or nerve may be injured: and even though no serious bleeding may take place immediately, an artery may give way when the wound begins to soften and discharge. The patient should therefore be watched with care. If a large quantity of scarlet blood has come from the wound, and then suddenly ceased, or if there is any other reason to suppose that a great artery has been injured, the patient must be kept perfectly still, on low diet, and a purgative given. If he is a very full-blooded man, and the wound is attended with much throbbing, swelling, and pain, it may be

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

45 |

necessary to bleed him. No wine or spirits must be given in this case: everything must be avoided that might provoke a return of bleeding from the wound.

When the end of a limb has been taken clean off by a cannonshot, there is not usually much bleeding, because the blood-vessels shrink back among the flesh and close themselves; but there is some risk of their bleeding again when the stump begins to inflame: in that case they must be sought for on the face of the stump and tied. The hot iron is the only other treatment, as it is impossible to make pressure by compresses effectually on the end of a stump.

Pieces of clothing are commonly carried in by the ball; and these, together with splinters of wood, bone, etc., must be removed, if it can be done without violence. The wound sometimes heals over them, and pieces of cloth are sometimes discharged many months afterwards.

Gun-shot wounds are commonly followed by a severe shock, from which the patient sometimes does not recover. Brandy or other stimulants must be given, if necessary, to revive him. The treatment afterwards is the same as that directed for torn wounds of all kinds. (See page 41.)

Fragments or Shell inflict ragged and fearful wounds, also accompanied with severe shock. They must be treated in the same way. The effects of Grape and Canister are similar to those of round bullets, in proportion to their weight. Grapeshot sometimes lodge themselves in the body. Spent Shot or fragments of shells sometimes break bones and reduce the flesh to a pulp (which afterwards mortifies), without breaking the skin.

POISONED WOUNDS.

Severe Poisoned Wounds, whether from the bite or sting of an animal or inflicted by a poisoned weapon, are commonly followed by rapid swelling, numbness, faintness, giddiness, and vomiting; and often by cold sweats, convulsions, and death, or by extensive abscesses.

First endeavour to prevent the poison from spreading, if the

|

|

46 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

wound has been received within a few minutes. Place a tie round the limb just above the wound. Instantly suck the wound with your mouth; this may be done with perfect safety unless there are any cuts or raw places about your mouth. Then the wound should be thoroughly rubbed with wetted Lunar Caustic; or cut entirely out, if anyone has sufficient boldness and skill; or well burnt with a white-hot iron. A cupping-glass may be used to draw out fluids from the wound. Hartshorn, hot vinegar, or salt, may be applied if nothing else is at hand. The wound should be soaked in hot water to encourage bleeding.

The chief internal remedy relied on in the South-Western States of America for the bite of a rattlesnake is whisky. It is given in enormous quantity – as much as two bottles – without producing drunkenness, and seems to have the power of neutralizing the poison. Any other spirit or wine, whatever may be at hand, should be given plentifully, with water. If the patient cannot swallow, inject spirits and water into the bowels.

Poisoned Wounds of the fingers and toes are more dangerous than those of other parts of the body. The rapidity with which the poison of the rattlesnake or cobra infects the whole system is wonderful. A very few minutes are sufficient,

When the first danger has been averted, the patient’s bowels should be opened with two Purging Pills, followed by half an ounce of Castor Oil on the following morning. He may have a good diet, without solids, and some wine daily.

Smaller injuries of this kind, such as the bite of scorpions, centipedes, hornets, bees, wasps, mosquitoes, etc., should be treated by applying Hartshorn or Sal-volatile. Carbonate of Soda or Chalk, or rags wet with Goulard’s Lotion (No. 22) or vinegar. If the sting is left in the flesh it must be extracted: a magnifying glass may be necessary to find it. If a man be stung in many places at once he may suffer severe collapse, and require strong spirits and water, or wine. A poultice of Ipecacuanha Powder is strongly recommended by some.

The bites and stings of insects are usually most painful to those who are in the habit of drinking spirits and of eating too much.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

47 |

BURNS AND SCALDS.

In slight cases the skin is merely reddened. In more severe cases blisters are raised, under which (if they are not opened) a new skin is formed. In the worst cases the burnt part is killed, and separates itself from the body as a dead substance, if the patient lives long enough. If the patient is greatly depressed and stupified by the accident, and feels no pain, it is a bad sign, and you must give him beef-tea and brandy at once; the burnt part must be kept covered up from the air. If the injury is slight, one of the following remedies will suffice; a coating of olive oil, or rag spread with fresh lard, or simple ointment, or soaked in Goulard’s Lotion, or in a cup of water in which two teaspoonfuls of Carbonate of Soda have been dissolved; or repeated coatings of flour, or of thick soap-lather. The part may be first soaked in warm water. After four or five days, if the place begins to discharge, it may be dressed with rag dipped in Zinc Lotion. In severe cases the part must be covered with cotton-wool on which Olive Oil, or a mixture of Linseed Oil and Lime-water, has been spread. The discharges are generally offensive, so that the dressings require to be changed often; but they should not be disturbed unnecessarily, so that the air may be kept from the sore. If portions of the wool stick to the surface they should not be pulled away. A light bandage should be used to keep the dressings in place. The part must be protected from cold.

Never open the blisters. If they break, do not cut away the skin. If there is great pain, a linseed meal poultice on which thirty or forty drops of Laudanum have been sprinkled, may be applied. The wounds are often very long in healing, and are painful and exhausting for weeks or months. In these cases poultices, with a teaspoonful of Olive Oil and ten drops of Goulard’s Extract mixed in them, are useful. If the sore becomes very foul, Carbolic Acid Lotion must be freely applied.

The bowels must be regulated, as in all other cases of injury; and the diet must be light and nourishing.

|

|

48 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

THE EFFECTS OF COLD.

When a person is exposed to great cold, especially if it be accompanied with wind, and he be fatigued and hungry, he is liable to feel an almost irresistible desire to lie down where he is and sleep. If he does so, he never wakes. The only thing to be done is to struggle against the feeling, and push on for shelter. If one of a party is affected in this way, the others must shake and rouse him, and not listen to his entreaties to be left alone. When shelter is reached, he must not be taken directly into a hot room or cabin, but have his warmth and circulation gradually restored by rubbing his limbs, &c. If this cannot be done, he becomes perfectly pale and cold, the pulse diminishes to a thread, and the breathing becomes faint, and ceases. The limbs are flexible while life lasts.

The cold may affect a part of the body, while the remainder does not feel its influence. This is called Frost-bite, and often happens to seamen in the North and South Seas, especially if they are natives of hot countries, or have intemperate habits. The signs of it are that the part affected, which is most commonly a finger or toe, or the nose, ears, or lips, becomes first of a dull red, and then of a pale tallowy colour, and is insensible to feeling, and shrunken. The patient is usually unconscious of it, until he is told of it by a comrade. The consequences, if the injury is neglected, are that the part dies, becomes black and gangrenous, and falls off, leaving a ragged sore. Sometimes a hand or foot has been lost in this way.

The best remedy is to rub the part briskly with snow or pounded ice, without a moment’s delay. This must be continued until sensation returns. The patient must not be brought near a fire, nor into a warm room. No warm applications must be used until after inflammation has set in, and dead parts have begun to separate. Poultices are then required. When the inflammation has ceased and the wound is clearing, a little Basilicon Ointment spread on lint may be applied. If the sore is sluggish, it may be touched now and then with Lunar Caustic. Give nourishing food

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

49 |

with wine and quinine, and be careful to have the injured part protected from the cold for some time afterwards.

The touch of intensely cold metals, such as frozen quicksilver, has similar effects to that of hot metals.

Chilblains are produced more easily in some persons than others, but most easily in rheumatic persons, by sudden changes of temperature, such as bringing cold feet or hands close to a fire. But they may come on in spite of all precautions. If unbroken, they should be gently rubbed with Turpentine Liniment, Opodeldoc, or Spirits of Wine with Camphor dissolved in it, and covered with flannel. If blisters rise, they must not be broken, but the Liniment should be applied with a feather. When the skin breaks and an ulcer is formed, it may give a great deal of trouble. If there is great pain and heat, poultices must be applied; but they should be exchanged, as soon as the heat has abated, for Basilicon Ointment spread on lint.

—————

BRUISES AND STRAINS.

When the skin is not broken, and no bone has been injured, the bruised or contused part should be bathed with hot water, and with warm vinegar. Cloths wet with this or with Goulard’s Lotion should be applied. If the patient prefers it, the applications may be cold.

Bruises of the head should be carefully watched, on account of their tendency to inflammation, and the possibility of their being accompanied with concussion of the brain. Heavy blows on the Spine and Loins are often more serious than wounds, and should be also carefully watched. Either of these injuries may be followed by palsy of the parts below the injured point.

If symptoms of Concession of the Brain occur, they always follow the injury immediately. The patient is more or less deeply insensible, and in slight cases can be roused for a moment to answer a question. The skin is pale and cold, the pulse feeble and irregular, and the breathing slow. After a time the patient moves his limbs about and vomits more or less violently, and then

|

|

50 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

usually recovers his senses. If the pulse and breathing remain very weak for many hours; if the eyelids do not move when touched, and the legs are not drawn up when the soles of the feet are tickled, the case is likely to end badly.

When the patient has recovered his senses one of the following things may occur: – 1. Inflammation of the Brain. This rarely appears till a week after the injury, or sometimes later. It is known by a feeling of tightness and pain in the head, quick pulse, confusion of mind, disturbed sleep, want of appetite, and general sickness, followed by burning heat of skin, occasional shivering fits, throbbing at the temples, dry tongue, costive bowels, violent headache, and inability to bear light or sound. The patient often raves violently. If these symptoms are not relieved, the pulse sinks, he becomes insensible, with low muttering delirium, palsy, squinting, or convulsions, and death soon follows.

A part only of these symptoms may occur. The treatment to be adopted consists of perfect quiet of mind and body; free purging; low diet; and cold applied to the head. Put him in as quiet a place as possible, not in a bright light; cut off all his hair, keep his head raised, and apply all over it a bag of pounded ice, or cloths wet with the coldest water procurable. If he can swallow, and is not inclined to sleep, give him ten grains of Dover’s Powder every four or six hours, stopping it as soon as he becomes drowsy. Give him also three Purging Pills, followed in two hours by a full dose of Black Draught. If no effect is produced, repeat them. If he cannot swallow, do not attempt to force things down his throat, but give him an injection of a pint of warm gruel or barley-water, with two tablespoonfuls each of common salt, soft sugar, and sweet oil. If the injection comes away without relieving the bowels, repeat it. Soak his feet in hot mustard and water, and keep his body warm. But disturb him as little as possible in applying these remedies. If they fail, put a blister to the head (having previously shaved it) or to the nape of the neck.

2. Pressure on the Brain, from blood which has escaped

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

51 |

within the skull. This often comes on after an interval, when the patient has recovered his senses from the first shock. It begins gradually, the pulse being usually full and slow, the skin hot and perspiring, the breathing of a puffing and snoring character, and the pupils of the eyes large and fixed. There is also usually some palsy, and the patient may pass his urine and motions under him. The treatment is the same as in the last case.

3. A condition of semi-stupor, which may last some days, followed by an infirm state of body and mind, with loss of memory and impaired hearing and smell, and a liability to violent excitement from drink or other causes. It is common for the patient to forget the circumstances which preceded the accident, and those which followed his return to consciousness.

In all these cases you should be careful to see that he passes his water freely. If he does not, and a round swelling, caused by the full bladder, can be felt at the lower part of the belly, the water must be drawn off by a catheter. (See Retention of Urine.)

The diet at first must consist entirely of slops. If he is very low, wine or brandy may be given. He must avoid fatigue, hot sunshine, excitement, and drink, for a long time.

Erysipelas, or St. Anthony’s fire, is very liable to follow blows on the scalp. (See Erysipelas.)

Blows on the Chest sometimes produce Pleurisy, but they may generally be treated by hot fomentations, rest, and a purgative. Broken ribs must be looked for and treated as directed farther on.

A severe blow on the Stomach is often followed by immediate death. If the bowels are burst (which may happen without the skin being broken) death almost inevitably follows after a short time. Let the patient lie still on his back, with his head low: give him wine or weak brandy and water every fifteen minutes until he rallies. Keep the feet warm. Give him an Opium Pill every third hour until three have been taken, unless he appears drowsy. Stop the wine as soon as the pulse becomes stronger and the warmth of the body returns, and treat him as directed after Wounds of the Belly, at p.42.

|

|

52 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

The Spine is known to have been injured by the loss of feeling and power of motion below the part struck. The urine and motions will probably be passed without the patient’s knowledge. Place a large poultice along the back-bone, and in other respects treat him as directed for blows on the head; of course applying the remedies to the spine instead of to the head. All these cases are troublesome, and require careful nursing.

Bruises of other parts of the body are seldom followed by serious consequences. If the swelling is very great, a few leeches, if they are procurable, may be applied.

When a joint has been strained, and becomes hot and painful, bathe it in hot water or vinegar, and apply cloths wet with water in which Laudanum has been mixed, in the proportion of one or two drachms to a pint. Use occasionally the Opodeldoc embrocation, or a mixed one composed as follows: – Opodeldoc, 1-1/2 oz., Spirits of Hartshorn, 1/2 oz., Laudanum, 1/4 oz. Rub a little of this into the painful part gently, for half an hour at a time, and apply a light bandage.

Immediately on receiving a strain it is a good plan to hold the limb for some minutes in running water.

Complete rest for the limb, regular diet, and opening medicine, are necessary to rapid recovery. After the inflammation has disappeared, if the part continues to feel stiff and weak, pour cold water on it for two or three minutes every morning, and rub it well with a rough towel.

—————

DISLOCATIONS.

A dislocation is the putting a bone or bones out of joint. It is sometimes done by a direct blow, but more commonly by a twist, as in falling when one is tripped up.

In all dislocations it is of the greatest importance to attempt to put the bone in again as early as possible, before the limb has begun to swell. Afterwards, if great swelling and inflammation come on, the patient must be put on low diet and purged, if he be strong enough to bear it; if he be a very robust man it may be necessary to bleed him.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

53 |

If there is a difficulty in putting in a displaced bone, the patient should be placed in a warm bath before the attempt is made.

When a dislocation is suspected to exist, compare the injured side with the sound side, and note the difference.

DISLOCATIONS OF PARTICULAR JOINTS.

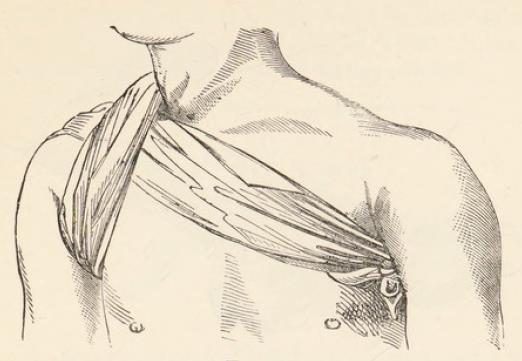

Shoulder. – This is more often put out than any other joint. The arm bone is commonly displaced downwards, and its round head can be felt in the arm-pit if the limb be raised a little. At the same time the shoulder is flattened, and a slight hollow may be felt where the head of the bone ought to be, just below the point of the shoulder; the elbow sticks out from the side, and cannot be made to touch the ribs; the arm is slightly lengthened, and the patient is unable to use it. There is considerable pain, which is relieved by supporting the arm.

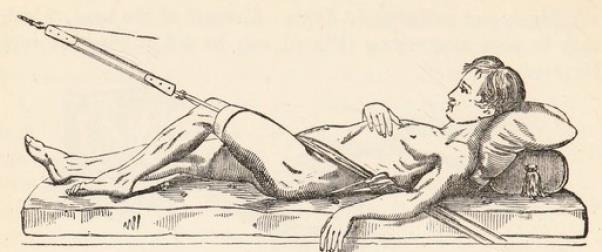

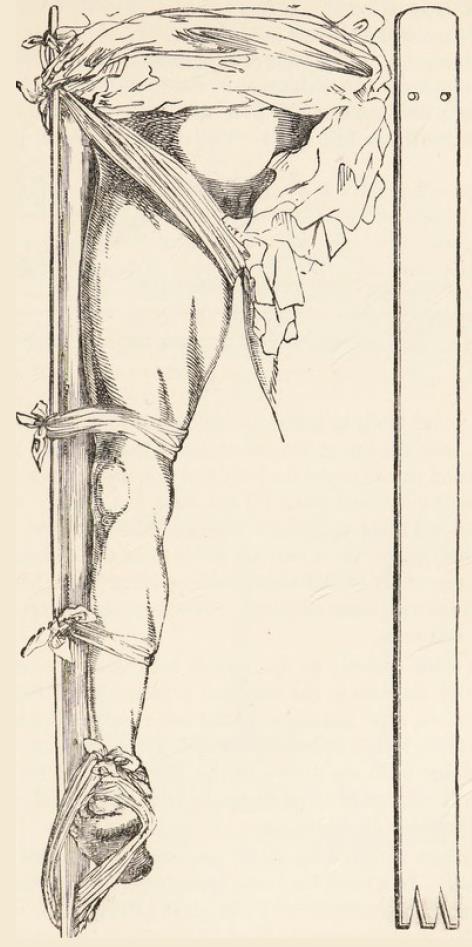

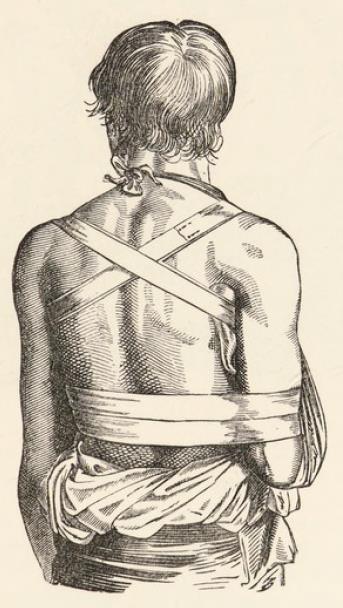

Let the patient lie down on his back. Sit down beside him on the deck, on the side on which the dislocation is, facing the opposite way to him. Put a towel round the arm with a clove hitch, just above the elbow (Fig.8); put the heel of your foot which is next to his body (with the boot off) into the arm-pit,

Fig.8.

Fig.8.

|

|

54 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

and pull slowly and evenly on the arm until the bone goes with a snap into the socket. On comparing it with the sound side you will be easily able to tell whether the bone is in its place again.

Another method is to let the patient sit, pass a jack-towel round his body, close under the arm-pit of the injured side, and make it fast to a stanchion on the other side, so as to keep the body fixed; then pull his arm straight out from his body with a small block and tackle; stand behind him, and help the bone into place by putting your knee under the arm-pit.

As soon as the bone has been replaced in its natural position, put a large wad of tow in the arm-pit, put the arm in a sling, and keep it bandaged to the side for a few days. The accident when it has happened once, is very liable to be repeated; the arm, therefore, must not be used for hard work for some weeks.

The oftener a joint has been dislocated, the more easily it is replaced, and the more readily it slips out again.

Remember, in all cases, a steady and even pull is far more effective than any sudden or violent efforts.

Elbow. – The fore-arm has two bones, the heads of which, in dislocation of the elbow, are generally driven backwards, and may be felt sticking out behind, while the elbow is bent and immovable. Or one of the bones (the outer one) may be forced up in front of the joint.

Let the patient be seated, and let the upper arm be firmly held by one man, while another pulls the hand straight down. Take hold of the elbow, and try to help the ends of the bones into their places, by pushing them steadily downwards. When the pull has been kept for some time, suddenly bend the arm, without giving the patient warning, and the bones will probably go back into their places.

Put the arm in a sling until inflammation has subsided.

Wrist. – This does not often become dislocated without fracture. The joint is easily seen to be out of shape. It is restored by steadily pulling on the hand.

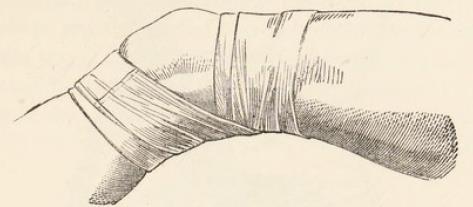

Finger. – Often a troublesome dislocation to deal with, especially if not treated at once. Tie a tape with a clove hitch round

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

55 |

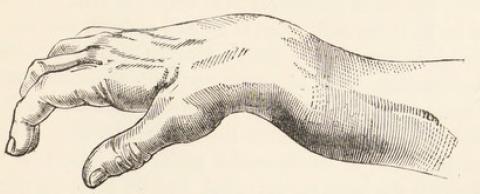

the finger, and pull straight down. The end of the bone, which may be seen sticking up (Fig.9), can be felt to go back into its place.

Fig.9

Fig.9

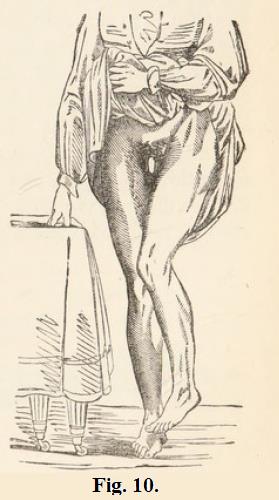

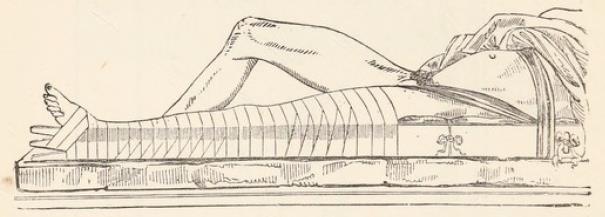

Hip. – The most usual mode of dislocation is that in which the thigh bone is displaced upwards and backwards. The limb is about two inches shorter than the other, and turned inwards, so that the toes rest on the opposite instep (Fig. 10). The hip is less

prominent than the sound one, and the legs cannot be separated. If the patient is thin, the head of the bone may be felt a little behind the hip.

prominent than the sound one, and the legs cannot be separated. If the patient is thin, the head of the bone may be felt a little behind the hip.

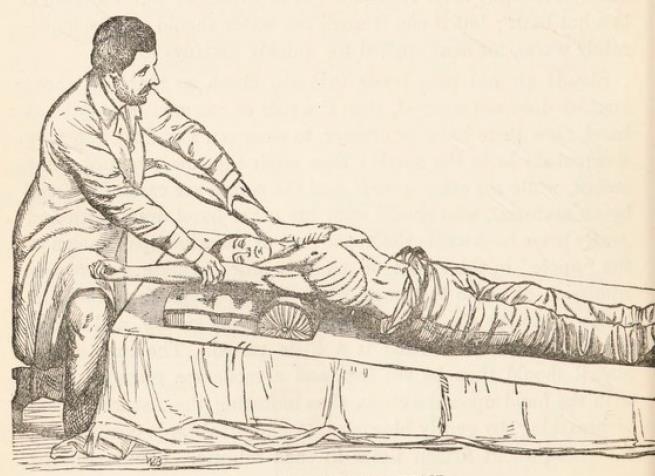

Lay the patient on his back. Make fast the upper end of the limb by a stout jack-towel passed under the fork, and secured to a stanchion behind him. Fasten a small block and tackle to the lower end of the thigh, just above the knee, and let a man pull slowly and steadily. Let the direction of the pull be downwards, inclining a little across to the opposite side (Fig. 11). Put another jack-towel round the upper part of the thigh, and round your own neck, so as to enable you to lift the head of the bone towards its proper place. Let another man turn the foot and leg slightly inwards. After a time the bone will usually go into its place suddenly with a snap.

|

|

56 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Knee. – The joint itself is seldom dislocated. If it is, the bones can be easily felt to be out of their places, and the leg must be pulled straight down until they come into them. The Knee-cap is more often thrown out of place, and usually to the inner side of the joint. In this case the leg must be straightened, and held up towards the body, and the knee-cap can then be pushed back into its place with the fingers and thumbs. A straight splint must be kept bound to the limb, behind the joint, so as to prevent the knee from bending for a fortnight or more.

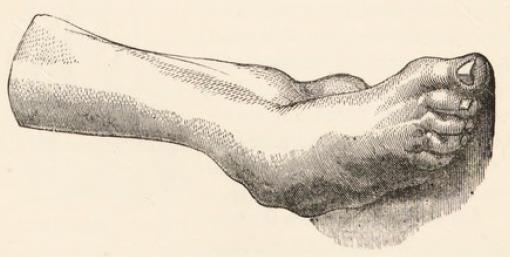

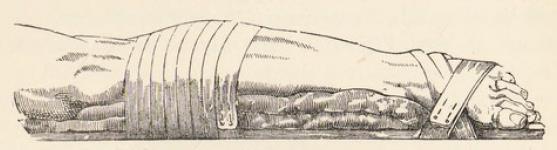

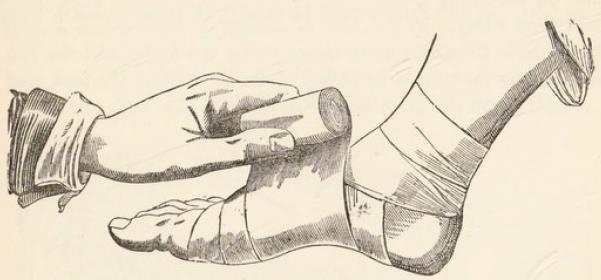

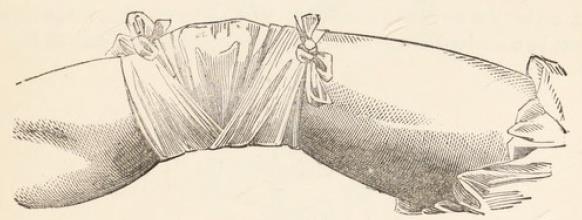

Ankle. – A jump from a height or any violent wrench may cause this dislocation, and very likely break one of the bones, or drive it through the skin. The shape of the joint is altered, and the foot rendered immovable (Fig. 12). The foot must be pulled

Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

57 |

steadily straight downwards, and when the bones have returned to their places, the limb must be bound to an  shaped splint, reaching as high as the knee, on the inner side of the leg. Another may be put on the outer side. The knee should remain bent, both during the attempt to put the bones in place, and afterwards. The patient should lie on the injured side. shaped splint, reaching as high as the knee, on the inner side of the leg. Another may be put on the outer side. The knee should remain bent, both during the attempt to put the bones in place, and afterwards. The patient should lie on the injured side.

If the skin is broken by the bones being thrust through it, the case is more serious, and the joint is sure to become inflamed. All dirt must be washed away with warm water, and if any loose fragments of bone are sticking out, they must be gently removed with the fingers. A piece of lint, dipped in the blood, should be placed on the wound, and allowed to stick to it, so as to exclude the air, and cold lotions must be kept constantly applied. The splints should be arranged, if possible, so as not to be over the wound. Care must be taken to keep the foot in good position, like that of the sound side. The diet must be simple, and no wine nor spirits must be given, unless the patient is low. The discharge may probably be exhausting, and the recovery may take many months.

Foot. – Some of the bones of the foot, or of the toes, may be displaced, and can be set right by steadily pulling in the direction of the length of the foot.

Jaw. – If a man receives a blow on the chin when his mouth is wide open, the lower jaw may be displaced. The mouth is fixed open, and the saliva dribbles from it. Wrap several folds of a thick towel round each of your thumbs, and, while the man sits down in front of you, thrust both thumbs as far back as you can upon the lower teeth, and press firmly down, while you press the point of the chin upwards and forwards with your fingers. The jaw goes into its place with a snap.

Collar-bone. – This may be knocked away from its attachments, usually at the inner end. The treatment is the same as for fracture of the bone. (See p.61.)

—————

|

|

58 |

the seaman's medical guide.

|

|

FRACTURES OR BROKEN BONES.

A bone is known to be broken by the following signs: – 1. It is altered in shape as compared with that of the sound side. 2. Its two parts can be moved upon one another; that is, there is a joint where there ought not to be one. 3. The broken ends can be felt or heard to grate upon one another when they are moved.

The object to be aimed at in the treatment of broken bones is to replace the broken ends in their natural position, and to keep them there until they have firmly united. They will not unite unless the part is kept perfectly at rest. The time required varies from three to six or eight weeks, or longer, according to the size of the bone and the health of the patient.

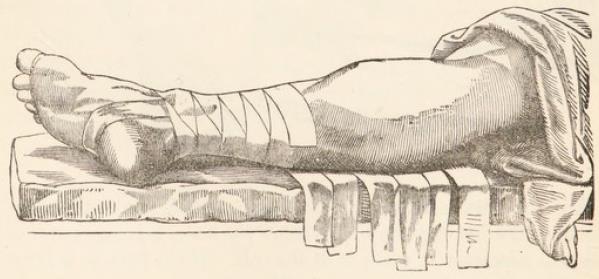

A fracture is called simple when the skin is not broken, and compound when there is a wound reaching down to the bone. Compound fractures are much more serious than simple, because the air can get at the broken bone. Therefore in moving a map with a broken limb, be careful to tie the limb to a flat piece oi board, or to tie it up in a bundle of stiff straws, reeds, canes, or anything that may be at hand, before you lift him: otherwise one of the ends of the bone may work its way through the skin as you carry him. If a leg or thigh be broken, tie both limbs together, putting a pad between them (Fig. 13), and lay him on the sound side.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

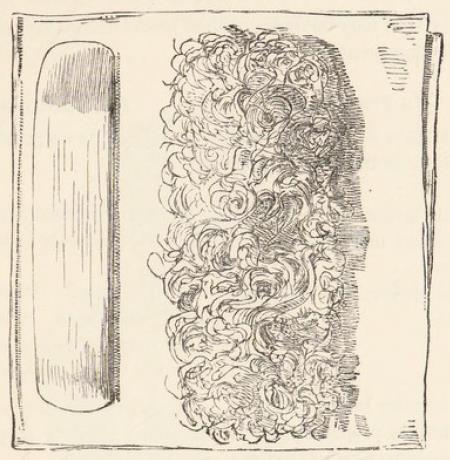

Splints are flat pieces of wood padded with tow or any soft material, which are used to keep the broken bone steady during

|

|

|

the seaman's medical guide.

|

59 |

recovery. Any flat piece of wood, shaped with a knife to the required size, with the corners rounded, may be laid on a piece of cloth, with some tow arranged by it, as shewn in Fig. 14, and rolled up and secured with pins so as to make a very efficient splint.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.