Revised Jun 12 2021

← Pipon/Tagus Home Narratives Pitcairners/Beechey →

John Adams's Story of the Mutineers at Pitcairn

as told to Captain Beechey of the Blossom

[The Blossom sighted Pitcairn Island December 4, 1825.]

THE interest which was excited by the announcement of Pitcairn Island from the masthead brought every person upon deck, and produced a train of reflections that momentarily increased our anxiety to communicate with its inhabitants; to see and partake of the pleasures of their little domestic circle; and to learn from them the particulars of every transaction connected with the fate of the Bounty: but in consequence of the approach of night this gratification was deferred until the next morning, when, as we were steering for the side of the island on which Captain Carteret has marked soundings, in the hope of being able to anchor the ship, we had the pleasure to see a boat under sail hastening toward us. At first the complete equipment of this boat raised a doubt as to its being the property of the islanders, for we expected to see only a well-provided canoe in their possession, and we therefore concluded that the boat must belong to some whaleship on the opposite side; but we were soon agreeably undeceived by the singular appearance of her crew, which consisted of old Adams and all the young men of the island.

Before they ventured to take hold of the ship, they inquired if they might come on board, and upon permission being granted, they sprang up the side and shook every officer by the hand with undisguised feelings of gratification.

The activity of the young men outstripped that of old Adams, who was consequently almost the last to greet us. He was in his sixty-fifth year, and was unusually strong and active for his age, notwithstanding the inconvenience of considerable corpulency. He was dressed in a sailor's shirt and trousers and a low-crowned hat, which he instinctively held in his hand until desired to put it on. He still retained his sailor's gait, doffing his hat and smoothing down his bald forehead whenever he was addressed by the officers.

It was the first time he had been on board a ship of war since the mutiny, and his mind naturally reverted to scenes that could not fail to produce a temporary embarrassment, heightened, perhaps, by the familiarity with which he found himself addressed by persons of a class with those whom he had been accustomed to obey. Apprehension for his safety formed no part of his thoughts; he had received too many demonstrations of the good feeling that existed towards him, both on the part of the British government and of individuals, to entertain any alarm on that head; and as every person endeavoured to set his mind at rest, he very soon made himself at home.*

* Since the MS. of this narrative was sent to press intelligence of Adams' death has been communicated to me by our Consul at the Sandwich Islands.

The young men, ten in number, were tall, robust, and healthy, with good-natured countenances, which would any where have procured them a friendly reception; and with a simplicity of manner and a fear of doing wrong, which at once prevented the possibility of giving offence. Unacquainted with the world, they asked a number of questions which would have applied better to persons with whom they had been intimate, and who had left them but a short time before, than to perfect strangers; and inquired after ships and people we had never heard of. Their dress, made up of the presents which had been given them by the masters and seamen of merchant ships, was a perfect caricature. Some had on long black coats without any other article of dress except trousers, some shirts without coats, and others waistcoats without either; none had shoes or stockings, and only two possessed hats, neither of which seemed likely to hang long together.

They were as anxious to gratify their curiosity about the decks, as we were to learn from them the state of the colony, and the particulars of the fate of the mutineers who had settled upon the island, which had been variously related by occasional visiters and we were more especially desirous of obtaining Adams own narrative; for it was peculiarly interesting to learn from one who had been implicated in the mutiny, the facts of that transaction, now that he considered himself exempt from the penalties of his crime.

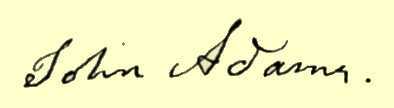

I trust that, in renewing the discussion of this affair, I shall not be considered as unnecessarily wounding the feelings of the friends of any of the parties concerned; but it is satisfactory to show, that those who suffered by the sentence of the court-martial were convicted upon evidence which is now corroborated by the statement of an accomplice who has no motive for concealing the truth. The following account is compiled almost entirely from Adams' narrative, signed with his own hand, of which the following is a fac-simile,

.

.

But to render the narrative more complete, I have added such additional facts as were derived from the inhabitants, who are perfectly acquainted with every incident connected with the transaction. In presenting it to the public, I vouch, only, for its being a correct statement of the above-mentioned authorities.

[A recounting of the details of the mutiny have been excised. It is available here.]

The mutineers now bade adieu to all the world, save the few individuals associated with them in exile. But where that exile should be passed, was yet undecided: the Marquesas Islands were first mentioned; but Christian, on reading Captain Carteret's account of Pitcairn Island, thought it better adapted to the purpose, and accordingly shaped a course thither. They reached it not many days afterwards*; and Christian, with one of the seamen, landed in a little nook, which we afterwards found very convenient for disembarkation. They soon traversed the island sufficiently to be satisfied that it was exactly suited to their wishes. It possessed water, wood, a good soil, and some fruits. The anchorage in the offing was very bad, and landing for boats extremely hazardous. The mountains were so difficult of access, and the passes so narrow, that they might be maintained by a few persons against an army; and there were several caves, to which, in case of necessity, they could retreat, and where, as long as their provision lasted, they might bid defiance to their pursuers. With this intelligence they returned on board, and brought the ship to an anchor in a small bay on the northern side of the island, which I have in consequence named "Bounty Bay," where every thing that could be of utility was landed, and where it was agreed to destroy the ship, either by running her on Jan 23, 1790 shore, or burning her. Christian, Adams, and the majority, were for the former expedient; but while they went to the fore-part of the ship, to execute this business, Mathew Quintal set fire to the carpenter's store-room. The vessel burnt to the water's edge, and then drifted upon the rocks, where the remainder of the wreck was burnt for fear of discovery. This occurred on the 23d January, 1790.

Jan 15, 1790

* [They left Tahiti on Sep 23, 1789, and landed at Pitcairn Jan 15, 1790.]

Upon their first landing they perceived, by the remains of several habitations, morais, and three or four rudely sculptured images, which stood upon the eminence overlooking the bay where the ship was destroyed, that the island had been previously inhabited. Some apprehensions were, in consequence, entertained lest the natives should have secreted themselves, and in some unguarded moment make an attack upon them; but by degrees these fears subsided, and their avocations proceeded without interruption.

A suitable spot of ground for a village was fixed upon with the exception of which the island was divided into equal portions, but to the exclusion of the poor blacks, who being only friends of the seamen, were not considered as entitled to the same privileges. Obliged to lend their assistance to the others in order to procure a subsistence, they thus, from being their friends, in the course of time became their slaves. No discontent, however, was manifested, and they willingly assisted in the cultivation of the soil. In clearing the space that was allotted to the village, a row of trees was left between it and the sea, for the purpose of concealing the houses from the observation of any vessels that might be passing, and nothing was allowed to be erected that might in any way attract attention. Until these houses were finished, the sails of the Bounty were converted into tents; and when no longer required for that purpose, became very acceptable as clothing. Thus supplied with all the necessaries of life, and some of its luxuries, they felt their condition comfortable even beyond their most sanguine expectation, and every thing went on peaceably and prosperously for about two years, at the expiration of which Williams, who had the misfortune to lose his wife about a month after his arrival, by a fall from a precipice while collecting birds' eggs, became dissatisfied, and threatened to leave the island in one of the boats of the Bounty, unless he had another wife; an unreasonable request, as it could not be complied with, except at the expense of the happiness of one of his companions: but Williams, actuated by selfish considerations alone, persisted in his threat, and the Europeans not willing to part with him, on account of his usefulness as an armourer, constrained one of the blacks to bestow his wife upon the applicant. The blacks, outrageous at this second act of flagrant injustice, made common cause with their companion, and matured a plan of revenge upon their aggressors, which, had it succeeded, would have proved fatal to all the Europeans. Fortunately, the secret was imparted to the women, who ingeniously communicated it to the white men in a song, of which the words were, "Why does black man sharpen axe? to kill white man." The instant Christian became aware of the plot, he seized his gun and went in search of the blacks, but with a view only of showing them that their scheme was discovered, and thus by timely interference endeavouring to prevent the execution of it. He met one of them (Ohoo) at a little distance from the village, taxed him with the conspiracy, and, in order to intimidate him, discharged his gun, which he had humanely loaded with powder only. Ohoo, however, imagining otherwise, and that the bullet had missed its object, derided his unskilfulness, and fled into the woods, followed by his accomplice Talaloo, who had been deprived of his wife. The remaining blacks, finding their plot discovered, purchased pardon by promising to murder their accomplices, who had fled, which they afterwards performed by an act of the most odious treachery. Ohoo was betrayed and murdered by his own nephew; and Talaloo, after an ineffectual attempt made upon him by poison, fell by the hands of his friend and his wife, the very woman on whose account all the disturbance began, and whose injuries, Talaloo felt he was revenging in common with his own.

Tranquility was by these means restored, and preserved for about two years; at the expiration of which, dissatisfaction was again manifested by the blacks, in consequence of oppression and ill treatment, principally by Quintal and McCoy. Meeting with no compassion or redress from their masters, a second plan to destroy their oppressors was matured, and, unfortunately, too successfully executed.

It was agreed that two of the blacks, Timoa and Nehow, should desert from their masters, provide themselves with arms, and hide in the woods, but maintain a frequent communication with the other two, Tetaheite and Menalee; and that on a certain day they should attack and put to death all the Englishmen, when at work in their plantations. Tetaheite, to strengthen the party of the blacks on this day, borrowed a gun and ammunition of his master, under the pretence of shooting hogs, which had become wild and very numerous; but instead of using it in this way, he joined his accomplices, and with them fell upon Williams and shot him. Martin, who was at no great distance, heard the report of the musket, and exclaimed, "Well done! we shall have a glorious feast to-day!" supposing that a hog had been shot. The party proceeded from Williams' toward Christian's plantation, where Menalee, the other black, was at work with Mills and McCoy; and, in order that the suspicions of the whites might not be excited by the report they had heard, requested Mills to allow him (Menalee) to assist them in bringing home the hog they pretended to have killed. Mills agreed; and the four, being united, proceeded to Christian, who was working at his yam-plot, and shot him. Thus fell a man, who, from being the reputed ringleader of the mutiny, has obtained an unenviable celebrity, and whose crime, if any thing can excuse mutiny, may perhaps be considered as in some degree palliated, by the tyranny which led to its commission. McCoy, hearing his groans, observed to Mills, "there was surely some person dying"; but Mills replied, "It is only Mainmast (Christian's wife) calling her children to dinner." The white men being yet too strong for the blacks to risk a conflict with them, it was necessary to concert a plan, in order to separate Mills and McCoy. Two of them accordingly secreted themselves in McCoy's house, and Tetaheite ran and told him that the two blacks who had deserted were stealing things out of his house. McCoy instantly hastened to detect them, and on entering was fired at; but the ball passed him. McCoy immediately communicated the alarm to Mills, and advised him to seek shelter in the woods; but Mills, being quite satisfied that one of the blacks whom he had made his friend would not suffer him to be killed, determined to remain. McCoy, less confident, ran in search of Christian, but finding him dead, joined Quintal (who was already apprised of the work of destruction, and had sent his wife to give the alarm to the others), and fled with him to the woods.

Mills had scarcely been left alone, when the two blacks fell upon him, and he became a victim to his misplaced confidence in the fidelity of his friend. Martin and Brown were next separately murdered by Menalee and Tenina; Menalee effecting with a maul what the musket had left unfinished. Tenina, it is said, wished to save the life of Brown, and fired at him with powder only, desiring him, at the same time, to fall as if killed; but, unfortunately rising too soon, the other black, Menalee, shot him.

Adams was first apprised of his danger by Quintal's wife, who, in hurrying through his plantation, asked why he was working at such a time? Not understanding the question, but seeing her alarmed, he followed her, and was almost immediately met by the blacks, whose appearance exciting suspicion, he made his escape into the woods. After remaining there three or four hours, Adams, thinking all was quiet, stole to his yam-plot for a supply of provisions; his movements however did not escape the vigilance of the blacks, who attacked and shot him through the body, the ball entering at his right shoulder, and passing out through his throat. He fell upon his side, and was instantly assailed by one of them with the butt end of the gun; but he parried the blows at the expense of a broken finger. Tetaheite then placed his gun to his side, but it fortunately missed fire twice. Adams, recovering a little from the shock of the wound, sprang on his legs, and ran off with as much speed as he was able, and fortunately outstripped his pursuers, who seeing him likely to escape, offered him protection if he would stop. Adams, much exhausted by his wound, readily accepted their terms, and was conducted to Christian's house, where he was kindly treated. Here this day of bloodshed ended, leaving only four Englishmen alive out of nine. It was a day of emancipation to the blacks, who were now masters of the island, and of humiliation and retribution to the whites.

Young, who was a great favourite with the women, and had, during this attack, been secreted by them, was now also taken to Christian's house. The other two, McCoy and Quintal, who had always been the great oppressors of the blacks, escaped to the mountains, where they supported themselves upon the produce of the ground about them.

The party in the village lived in tolerable tranquillity for about a week at the expiration of which, the men of colour began to quarrel about the right of choosing the women whose husbands had been killed; which ended in Menalee's shooting Timoa as he sat by the side of Young's wife, accompanying her song with his flute. Timoa not dying immediately, Menalee reloaded, and deliberately despatched him by a second discharge. He afterwards attacked Tetaheite, who was condoling with Young's wife for the loss of her favourite black, and would have murdered him also, but for the interference of the women. Afraid to remain longer in the village, he escaped to the mountains and joined Quintal and McCoy, who, though glad of his services, at first received him with suspicion. This great acquisition to their force enabled them to bid defiance to the opposite party; and to show their strength, and that they were provided with muskets, they appeared on a ridge of mountains, within sight of the village, and fired a volley which so alarmed the others that they sent Adams to say, if they would kill the black man, Menalee, and return to the village, they would all be friends again. The terms were so far complied with that Menalee was shot; but, apprehensive of the sincerity of the remaining blacks, they refused to return while they were alive.

Adams says it was not long before the widows of the white men so deeply deplored their loss, that they determined to revenge their death, and concerted a plan to murder the only two remaining men of colour. Another account, communicated by the islanders, is, that it was only part of a plot formed at the same time that Menalee was murdered, which could not be put in execution before. However this may be, it was equally fatal to the poor blacks. The arrangement was, that Susan should murder one of them, Tetaheite, while he was sleeping by the side of his favourite; and that Young should at the same instant, upon a sign being given, shoot the other, Nehow. The unsuspecting Tetaheite retired as usual, and fell by the blow of an axe; the other was looking at Young loading his gun, which he supposed was for the purpose of shooting hogs, and requested him to put in a good charge, when he received the deadly contents.

In this manner the existence of the last of the men of colour terminated, who, though treacherous and revengeful, had, it is feared, too much cause for complaint. The accomplishment of this fatal scheme was immediately communicated to the two absentees, and their return solicited. But so many instances of treachery had occurred, that they would not believe the report, though delivered by Adams himself until the hands and heads of the deceased were produced, which being done, they returned to the village. This eventful day was the 3d October, 1793. There were now left upon the island, Adams, Young, McCoy, and Quintal, ten women, and some children. Two months after this period, Young commenced a manuscript journal, which affords a good insight into the state of the island, and the occupations of the settlers. From it we learn, that they lived peaceably together, building their houses, fencing in and cultivating their grounds, fishing, and catching birds, and constructing pits for the purpose of entrapping hogs, which had become very numerous and wild, as well as injurious to the yam-crops. The only discontent appears to have been among the women, who lived promiscuously with the men, frequently changing their abode.

Apr 14, 1794

Young says, March 12, 1794, "Going over to borrow a rake, to rake the dust off my ground, I saw Jenny having a skull in her hand: I asked her whose it was? and was told it was Jack William's. I desired it might be buried: the women who were with Jenny gave me for answer, it should not. I said it should; and demanded it accordingly. I was asked the reason why I, in particular, should insist on such a thing, when the rest of the white men did not? I said, if they gave them leave to keep the skulls above ground, I did not. Accordingly when I saw McCoy, Smith, and Mat. Quintal, I acquainted them with it, and said, I thought that if the girls did not agree to give up the heads of the five white men in a peaceable manner, they ought to be taken by force, and buried." About this time the women appear to have been much dissatisfied; and Young's journal declares that, "since the massacre, it has been the desire of the greater part of them to get some conveyance, to enable them to leave the island." This feeling continued, and on the 14th April, 1794, was so strongly urged, that the men began to build them a boat; but wanting planks and nails, Jenny, who now resides at Otaheite, in her zeal tore up the boards of her house, and endeavoured, though without success, to persuade some others to follow her example.

Aug 15, 1794

On the 13th August following, the vessel was finished, and on the 15th she was launched: but, as Young says, "according to expectation she upset," and it was most fortunate for them that she did so; for had they launched out upon the ocean, where could they have gone? or what could a few ignorant women have done by themselves, drifting upon the waves, but ultimately have fallen a sacrifice to their folly? However, the fate of the vessel was a great disappointment, and they continued much dissatisfied with their condition; probably not without some reason, as they were kept in great subordination, and were frequently beaten by McCoy and Quintal, who appear to have been of very quarrelsome dispositions; Quintal in particular, who proposed "not to laugh, joke, or give any thing to any of the girls."

Oct 3, 1794

Nov 11, 1794

On the 16th August they dug a grave, and buried the bones of the murdered people: and on October 3d, 1794, they celebrated the murder of the black men at Quintal's house. On the 11th November a conspiracy of the women to kill the white men in their sleep was discovered; upon which they were all seized, and a disclosure ensued; but no punishment appears to have been inflicted upon them, in consequence of their promising to conduct themselves properly, and never again to give any cause "even to suspect their behavior." However, though they were pardoned, Young observes, "We did not forget their conduct; and it was agreed among us, that the first female who misbehaved should be put to death; and this punishment was to be repeated on each offence until we could discover the real intentions of the women." Young appears to have suffered much from mental perturbation in consequence of these disturbances; and observes of himself on the two following days, that "he was bothered and idle."

Nov 30, 1794

The suspicions of the men induced them, on the 15th, to conceal two muskets in the bush, for the use of any person who might be so fortunate as to escape, in the event of an attack being made. On the 30th November, the women again collected and attacked them; but no lives were lost, and they returned on being once more pardoned, but were again threatened with death the next time they misbehaved. Threats thus repeatedly made, and as often unexecuted, as might be expected, soon lost their effect, and the women formed a party whenever their displeasure was excited, and hid themselves in the unfrequented parts of the island, carefully providing themselves with fire-arms. In this manner the men were kept in continual suspense, dreading the result of each disturbance, as the numerical strength of the women was much greater than their own.

Dec 27, 1795

On the 4th of May 1795, two canoes were begun, and in two days completed. These were used for fishing, in which employment the people were frequently successful, supplying themselves with rockfish and large mackarel. On the 27th of December following, they were greatly alarmed by the appearance of a ship close in with the island. Fortunately for them, there was a tremendous surf upon the rocks, the weather wore a very threatening aspect, and the ship stood to the SE, and at noon was out of sight. Young appears to have thought this a providential escape, as the sea for a week after was "smoother than they had ever recollected it since their arrival on the island."

So little occurred in the year 1796, that one page records the whole of the events; and throughout the following year there are but three incidents worthy of notice. The first, their endeavour to procure a quantity of meat for salting; the next, their attempt to make syrup from the tee-plant (dracaena terminalis) and sugar-cane; and the third, a serious accident that happened to McCoy, who fell from a cocoa-nut tree and hurt his right thigh, sprained both his ancles and wounded his side. The occupations of the men continued similar to those already related, occasionally enlivened by visits to the opposite side of the island. They appear to have been more sociable; dining frequently at each other's houses, and contributing more to the comfort of the women, who, on their part, gave no ground for uneasiness. There was also a mutual accommodation amongst them in regard to provisions, of which a regular account was taken. If one person was successful in hunting, he lent the others as much meat as they required, to be repaid at leisure; and the same occurred with yams, taros, &c., so that they lived in a very domestic and tranquil state.

It unfortunately happened that McCoy had been employed in a distillery in Scotland; and being very much addicted to liquor, he tried an experiment with the tee-root, and on the 20th April 1798, succeeded in producing a bottle of ardent spirit. This success induced his companion, Mathew Quintal, to "alter his kettle into a still," a contrivance which unfortunately succeeded too well, as frequent intoxication was the consequence, with McCoy in particular, upon whom at length it produced fits of delirium, in one of which, he threw himself from a cliff and was killed. The melancholy fate of this man created so forcible an impression on the remaining few, that they resolved never again to touch spirits; and Adams, I have every reason to believe, to the day of his death kept his vow.

The journal finishes nearly at the period of McCoy's death, which is not related in it: but we learned from Adams, that about 1799 Quintal lost his wife by a fall from the cliff while in search of birds' eggs; that he grew discontented, and, though there were several disposable women on the island, and he had already experienced the fatal effects of a similar demand, nothing would satisfy him but the wife of one of his companions. Of course neither of them felt inclined to accede to this unreasonable indulgence; and he sought an opportunity of putting them both to death. He was fortunately foiled in his first attempt, but swore he would repeat it. Adams and Young, having no doubt he would follow up his resolution, and fearing he might be more successful in the next attempt, came to the conclusion, that their own lives were not safe while he was in existence, and that they were justified in putting him to death, which they did with an axe.

Such was the melancholy fate of seven of the leading mutineers, who escaped from justice only to add murder to their former crimes; for though some of them may not have actually embrued their hands in the blood of their fellow-creatures, yet all were accessary to the deed.

As Christian and Young were descended from respectable parents, and had received educations suitable to their birth, it might be supposed that they felt their altered and degraded situation much more than the seamen, who were comparatively well off: but if so, Adams says, they had the good sense to conceal it, as not a single murmur or regret escaped them; on the contrary, Christian was always cheerful, and his example was of the greatest service in exciting his companions to labour. He was naturally of a happy, ingenuous disposition, and won the good opinion and respect of all who served under him; which cannot be better exemplified than by his maintaining, under circumstances of great perplexity, the respect and regard of all who were associated with him up to the hour of his death; and even at the period of our visit, Adams, in speaking of him, never omitted to say "Mr. Christian."

Adams and Young were now the sole survivors out of the fifteen males that landed upon the island. They were both, and more particularly Young, of a serious turn of mind; and it would have been wonderful, after the many dreadful scenes at which they had assisted, if the solitude and tranquility that ensued had not disposed them to repentance. During Christian's lifetime they had only once read the church service, but since his decease this had been regularly done on every Sunday. They now, however, resolved to have morning and evening family prayers, to add afternoon service to the duty of the Sabbath, and to train up their own children, and those of their late unfortunate companions, in piety and virtue.

In the execution of this resolution, Young's education enabled him to be of the greatest assistance; but he was not long suffered to survive his repentance. An asthmatic complaint, under which he had for some time laboured, terminated his existence about a year after the death of Quintal, and Adams was left the sole survivor of the misguided and unfortunate mutineers of the Bounty. The loss of his last companion was a great affliction to him, and was for some time most severely felt. It was a catastrophe, however, that more than ever disposed him to repentance, and determined him to execute the pious resolution he had made, in the hope of expiating his offences.

His reformation could not, perhaps, have taken place at a more propitious moment. Out of nineteen children upon the island, there were several between the ages of seven and nine years; who, had they been longer suffered to follow their own inclinations, might have acquired habits which it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for Adams to eradicate. The moment was therefore most favourable for his design, and his laudable exertions were attended by advantages both to the objects of his care and to his own mind, which surpassed his most sanguine expectations. He, nevertheless, had an arduous task to perform. Besides the children to be educated, the Otaheitan women were to be converted; and as the example of the parents had a powerful influence over their children, he resolved to make them his first care. Here also his labours succeeded; the Otaheitans were naturally of a tractable disposition, and gave him less trouble than he anticipated; the children also acquired such a thirst after scriptural knowledge, that Adams in a short time had little else to do than to answer their inquiries and put them in the right way. As they grew up, they acquired fixed habits of morality and piety; their colony improved; intermarriages occurred: and they now form a happy and well-regulated society, the merit of which, in a great degree, belongs to Adams, and tends to redeem the former errors of his life.