Revised Jun 12 2021

← Delano/Foger Home Narratives Pipon/Tagus →

The Briton's Voyage to Pitcairn's Island

by Lieut. J. Shillibeer, R.M.

[This is chapter 5, which describes the stop at Pitcairn, excluding the first part, which is a retelling of the mutiny.]

We left the friendly Marquesians on the 2d of September, and were proceeding on our voyage to regain the port of Valparaiso, steering a course which ought, according to the charts and every other authority, to have carried us nearly 3 degrees of longitude to the eastward of Pitcairn's Island, and our surprize was greatly excited by its sudden and unexpected appearance. It was in the second watch when we made it. At day light we proceeded to a more close examination, and soon perceived huts, cultivation, and people; of the latter some were making signs, others launching their little canoes throught the surf, into which they threw themselves with great dexterity, and pulled towards us.

At this moment I believe neither Captain Bligh of the Bounty, nor Christian, had entered any of our thoughts, and in waiting the approach of the strangers, we prepared to ask them some questions in the language of those people we had so recently left. They came—and for me to picture the wonder which was conspicuous in every countenance, at being hailed in perfect English, what was the name of the ship, and who commanded her, would be impossible—our surprize can alone be conceived. The Captain answered, and now a regular conversation commenced. He requested them to come alongside, and the reply was, "We have no boat hook to hold on by." "I will throw you a rope" said the Captain. "If you do we have nothing to make it fast to" was the answer. However, they at length came on board, exemplifying not the least fear, but their astonishment was unbounded.

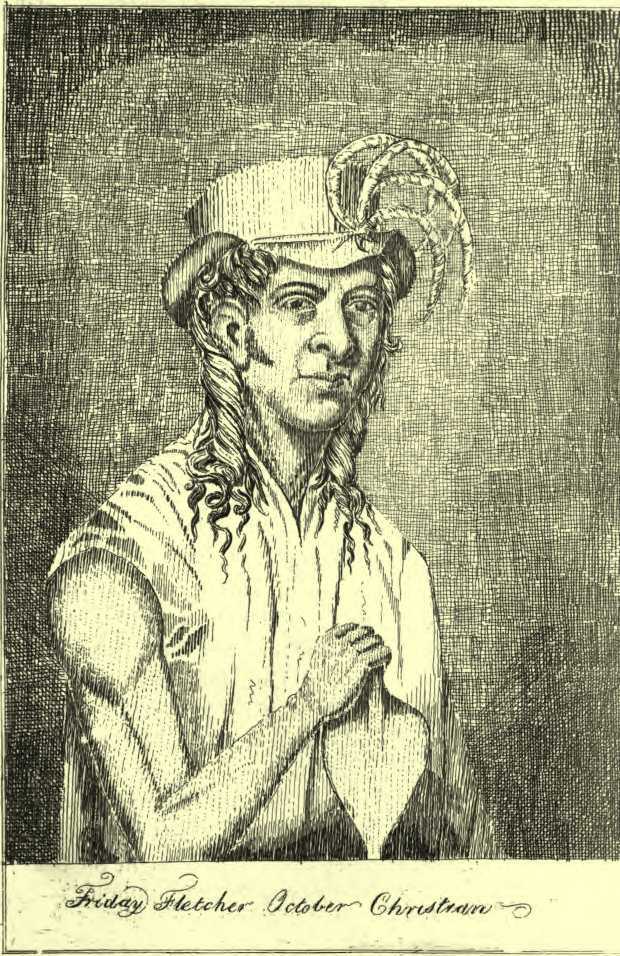

After the friendly salutation of good morrow, Sir, from the first man who entered (Mackey) [McCoy] for that was his name, "Do you know, said he, one William Bligh, in England? This question threw a new light on the subject, and he was immediately asked if he knew one Christian, and the reply was given with so much natural simplicity, that I shall here use his proper words. "Oh yes," said he, "very well, his son is in the boat there coming up, his name is Friday Fletcher October Christian. His father is dead now—he was shot by a black fellow." Several of them had now reached the ship, and the scene was become exceedingly interesting, every one betrayed the greatest anxiety to know the ultimate fate of that misled young man, of whose end so many vague reports had been in circulation, and those who did not ask questions, devoured with avidity every word which led to an elucidation of the mysterious temination of the unfortunate Bounty.

The questions which were now put were numerous, and as I am inclined to believe their being arranged with their specific answers, will convey to the reader, the circumstance as it really took place, with greater force than a continued relation, I shall adopt that plan, and those occurrences which did not lead immediately to the end of Christian, and the establishment of the colony, I will relate faithfully as they transpired.

Question.—Christian you say was shot?

Answer.—Yes he was.

Q.—By whom?

A.—A black fellow shot him.

Q.—What cause do you assign for the murder.

A.—I know no reason, except a jealousy which I have heard then existed between the people of Otaheite and the English—Christian was shot in the back while at work in his yam plantation.

Q.—What became of the man who killed him?

A.—Oh! that black fellow was shot afterwards by an Englishman.

Q.—Was there any other disturbance between the Otahetians and English, after the death of Christian?

A.—Yes, the black fellows rose, shot two Englishmen, and wounded John Adams, who is now the only remaining man who came in the Bounty.

Q.—How did Adams escape being murdered?

A.—He hid himself in the wood, and the same night, the women enraged at the murder of the English, to whom they were more partial than their countrymen, rose and put every Otahetian to death in their sleep. This saved Adams, his wounds were soon healed, and although old, he now enjoys good health.

Q.—How many men and women did Christian bring with him in the Bounty?

A.—Nine white men, six from Otaheite, and eleven women.

Q.—And how many are there now on the island?

A.—In all we have 48*.

* [This is an error, either by the author, editor, or printer. The population at the end of 1814 was 39, there were four births and two deaths during the year, the exact dates of all unknown. Staines, captain of the Briton, gave the number as 40.]

Q.—Have you ever heard Adams say how long it is since he came to the island?

A.—I have heard it is about 25 years ago.

Q.—And what became of the Bounty?

A.—After every thing useful was taken ouf of her, she was run on shore, set fire to, and burnt.

Q.—Have you ever heard how many years it is since Christian was shot?

A.—I understand it was about two years after his arrival on the island.

Q.—What became of Christian's wife?

A.—She died soon after Christian's son was born, and I have heard that Christian took forcibly the wife of one of the black fellows to supply her place, and which was the chief cause of his being shot.

Q.—Then, Fletcher October Christian is the oldest on the island, except John Adams, and the old women?

A.—Yes he is the first born on the island.

Q.—At what age do you marry?

A.—Not before 19 or 20.

Q.—Are you allowed to have more than one wife?

A.—No! we can have but one, and it is wicked to have more.

Q.—Have you been taught any religion?

A.—Yes, a very good religion.

Q.—In what do you believe?

A.—I believe in God the Father Almighty, &c. (Here he went through the whole of the Belief.)

Q.—Who first taught you this Belief?

A.—John Adams says it was first by F. Christian's order, and that he likewise caused a prayer to be said every day at noon.

Q.—And what is the prayer?

A.—It is,—"I will arise and go to my father, and say unto him Father, I have sinned against Heaven, and before thee, and am no more worthy of being called thy son."

Q.—Do you continue to say this every day?

A.—Yes, we never neglect it.

Q.—What language do you commonly speak?

A.—Always English.

Q.—But you understand the Otahetian?

A.—Yes, but not so well.

Q.—Do the old women speak English?

A.—Yes, but not so well as they understand it, their pronunciation is not good.

Q.—What countrymen do you call yourselves?

A.—Half English, and half Otaheite.

Q.—Who is your King?

A.—Why, King George to be sure.

Q.—Have you ever seen a ship before?

A.—Yes, we have seen four from the island, but only one stopped. Mayhew Folgier was the Captain, I suppose you know him?—No, we do not know him.

Q.—How long did he stay?

A.—Two days.

Q.—Should you like to go to England?

A.—No! I cannot, I am married, and have a family.

Before we had finished our interrogatories the hour of breakfast had arrived, and we solicited our half countrymen, as they styled themselves, to accompany us below, and partake of the repast, to which they acquiesced without much ceremony. The circle in which we had surrounded them being opened, brought to the notice of Mackey, a little black terrier. He was at first frightened, ran behind one of the officers, and looking over his shoulder said, pointing to the dog, "I know what that is, it is a dog, will it bite?" After a short pause he addressed himself to Christian, saying with great admiration, "It is a pretty thing to look at, is it not?"

The whole of them were inquisitive, and in their questions as well as answers, betrayed a very great share of natural abilities.

They asked the names of whatever they saw, and the purposes to which it was applied. This, they would say, was pretty,—that they did not like, and were greatly surprised at our having so many things which they were not possessed of in the Island.

The circumstance of the dog, the things which at each step drew their attention or created their wonder, retarded us on our road to the breakfast table, but arriving there, we had a new cause for surprize. The astonishment which had before been so strongly demonstrated in them, was now become conspicuous in us, even to a much greater degree than when they hailed us in our native language; and I must here confess I blushed when I saw nature in its most simple state, offer that tributre of respect to the Omnipotent Creator, which from an education I did not perform, nor from society had been taught its necessity. 'Ere they began to eat; on their knees, and with hands uplifted did they implore permission to partake in peace what was set before them, and when they had eaten heartily, resuming their former attitude, offered a fervent prayer of thanksgiving for the indulgence they had just experienced. Our omission of this ceremony did not escape their notice, for Christian asked me whether it was not customary with us also. Here nature was triumphant, for I should do myself an irreparable injustice, did I not with candour acknowledge, I was both embarrassed and wholly at a loss for a sound reply, and evaded this poor fellow's question by drawing his attention to the cow, which was then looking down the hatchway, and as he had never seen any of the species before, it was a source of mirth and gratification to him.

The hatred of these people to the blacks is strongly rooted, and which doubtless owes its origin to the eary quarrels which Christian and his followers had with the Otahetians after thier arrival at Pitcarnes; to illustrate which I shall here relate an occurrence which took place at breakfast.

Soon after young Christian had began, a West Indian Black, who was one of the servants, entered the gun-room to attend table as usual. Christian looked at him sternly, rose, asked for his hat, and said, "I don't like that black fellow, I must go," and it required some little persuasion, 'ere he would again resume his seat. The innocent Quashe was often reminded of the anecdote by his fellow servants.

After coming along side the ship, so eager were they to get on board, that several of the canoes had been wholly abandoned, and gone adrift. This was the occasion of an anecdote which will show most conspicuouly the good nature of their dispositions, and the mode resorted to in deciding a double claim. The canoes being brought back to the ship, the Captain ordered that one of them should remain in each, when it became a question to which that duty should devolve; however it was soon adjusted, for Mackey observed that he supposed they were all equally anxious to see the ship, and the fairest way would be for them to cast lots, as then there would be no ill will on either side. This was acceded to, and those to whom it fell to go into the boat departed without murmur.

I could wish it had been possible for us to have prolonged our stay for a few days, not only for our own gratification, but for the benefit which these poor people would have derived from it, for I am perfectly satisfied, from the interest every one took, nothing would have been withheld by the lowest of the crew which probability told him would add to their comfort: however this was impossible; for, from some cause on the part of the commissariat department, and which I cannot well explain, we were reduced to so comparatively small a portion of provisions, that it was necesary to use every means to expedite our return to South America, and after ascertaining the longitude to be in 130° 25′,W. and latitude 25° 4′ S. we again set sail and proceeded on our voyage.

No one but the Captains went ashore, which will be a source of lasting regret to me, for I would rather have seen the simplicity of that little village, than all the splendour and magnificence of a city.

I now lament it the more,because the conclusion of this chapter wil be from the relation of another, and I was willing to lay as little as possible before the reader, but to what I had myself been a witness; still, as I can rely on its veracity, I shall hope it will please. "After landing" said my friend "and we had ascended a little eminence, we were imperceptibly led through groupes of cocoa-nuts and bread-fruit trees, to a beautiful picturesque little village, formed on an oblong square, with trees, of various kinds irregularly interspersed. The houses small, but regular, convenient, and of unequalled cleanliness. The daughter of Adams, received us on the hill. She came doubtlessly as a spy, and had we taken men, or even been armed ourselves, would certainly have given her father timely notice to escape, but as we had neither, she waited our arrival, and conducted us to where her father was. She was arrayed in nature's simple garb, and wholly unadorned, but she was beauty's self, and needed not the aid of ornament. She betrayed some surprize—timidity was a prominent feature.

"John Adams is a fine looing old man, approaching to sixty years of age. We conversed with him a long time, relative to the mutiny of the Bounty, and the ultimate fate of Christian. He denied being accessary to, or having the least knowledge of the conspiracy, but he expressed great horror at the conduct of Captain Bligh, not only towards his men, but officers also. I asked him if he had a desire to return to England, and I must confess his replying in the affirmative, caused me great surprize.

"He told me he was perfectly aware how deeply he was involved; that by following the fortune of Christian, he had not only sacrificed every claim to his country, but that his life, was the necessary forfeiture for such an act, and he supposed would be exacted from him was he ever to return: notwithstanding all these circumstances, nothing would be able to occasion him so much gratification as that of seeing once more, prior to his death, that country which gave him birth, and from which he had been so long estranged.

"There was a sincerity in his speech, I can badly describe it—but it had a very powerful influence in persuading me these were his real sentiments. My interest was excited to so great a degree, that I offered him a conveyance for himself, with any of his family who chose to accompany him. He appeared pleased at the proposal, and as no one was then present, he sent for his wife and children. The rest of this little community surrounded the door. He communicated his desire, and solicited their acquiescence. Appalled at a request not less sudden than in opposition to their wishes, they were all at a loss for a reply.

His charming daugher although inundated with tears, first broke the silence.

"Oh do not, Sir," said she "take from me my father! do not take away my best—my dearest friend." Her voice failed her—she was unable to proceed—lent her head upon her hand, and gave ful vent to her grief. His wife too (an Otaheitian) expressed a lively sorrow. The wishes of Adams soon became known among the others, who joined in pathetic solicitation for his stay on the Island. Not an eye was dry—the big tear stood in those of the men—the women shed them in full abundance. I never witnessed a scene so fully affecting, or more replete with interest. To have taken him from a circle of such friends, would have ill become a feeling heart, to have forced him away in opposition to their joint and earnest entreaties, would have been an outrage on humanity.

"With assurances that it was neither our wish nor intention to take him from them against his inclination, their fears were at length dissipated. His daughter too had gained her usual serenity, but she was lovely in her tears, for each seemed to add an additional charm. Forgetting the unhappy deed which placed Adams in that spot, and seeing him only in the character he now is, at the head of a little community, adored by all, instructing all, in religion, industry, and friendship, his situation might be truly envied, and one is almost inclined to hope that his unremitting attention to the government and morals of this extraordinary little colony, will ultimately, prove an equivalent for the part he former took,—entitle him to praise, and should he ever return to England, ensure him the clemency of that Soverieign he has so much injured."

The young women have invariably beautiful teeth, fine eyes, and open expression of countenances, and looks of such simple innocence, and sweet sensibility, that renders their appearance at once interesting and engaging, and it is pleasing to add, their minds and manners were as pure and innocent, as this impression indicated. No lascivious looks, or any loose, forward manners, which so much distinguish the characters of the females of the other islands.

The Island itself has an exceedingly pretty appearance, and I was informed by Christian, every part was fertile and capable of being cultivated. The coast is every way bound with rocks, insomuch that they are at all times obliged to carry their little boats to the village, but the timber is of so light a nature that one man is adequate to the burden of the largest they have.

Each family has a separate allotment of land, and each strive to rival the other in their agricultural pursuits, which is chiefly confined to the propagation of the Yam, and which they have certainly brought to the finest perfection I ever saw. The bread-fruit and cocoa-nut trees, were brought with them in the Bounty, and have been since reared with great success. The pigs also came by the same conveyance, as well as goats and poultry. They had no pigeons, and I am sorry to say no one thought of leaving those few we had on board, with them.

The pigs have got into the woods, and many are now wild. Fish of various sorts are taken here, and in great abundance; the tackling is all of their own manufacturing, and the hooks, although beat out of old iron hoops, not only answer the purpose, but are fairly made.

Needles they also make from the same materials. Those men who came on board, were finely formed, and of manly features. Their height about 5 feet 10 inches. Their hair black and long, generally plaited into a tail.

They wore a straw hat, similar to those worn by sailors, with a few feathers stuck into them by way of ornament. On their shoulders was a mantle resembling the Chilinan Poncho which hung down to the knee, and round the waist, a girdle corresonding to that of the Indians at the Marquesas Islands, both of which are produced from the bark of trees growing on the Islands. They told me they had clothes on shore, but never wore them. I spoke to Christian particularly, of Adams, who assured me he was greatly respected, insomuch that no one acted in opposition to his wishes, and when they should lose him, their regret would be general. The inter-marriages which had taken place among them, have been the occasion of a relationship throughout the colony. There seldom happens to be a quarrel, even of the most trivial nature, and then, (using their own term,) is nothing more than a word of mouth quarrel, which is always referred to Adams for adjustment.

Several books belonging to Captain Bligh which were taken out of the Bounty were then in the possession of Adams, and the first voyage of Captain Cook was brought on board the Briton. In the title page of each volume the name of Captain Bligh was written, and I suppose in his own writing. Christian had written his name immediately under it without running his pen through, or defacing in the least that of Captain Bligh's. On the margins of several of the leaves were written, in pencil, numerous remarks on the work, but as I consider them to have been the private observations of Captain Bligh, and written unuspecting the much lamented event which subsequently took place, they shall by me be held sacred.

If the outline I have here given has not been adequate to the reader's expectation, I trust the short period in which I had to collect the materials, will, in some degree, plead my apology; under which impression I shall leave Pitcairn's Island, but not without a hope that its interesting inhabitants will receive that support from this country, the peculiarity of their situation so justly entitle them to, and proceed to Valparaiso, where we arrived after a voyage of 80 days, when we had neither bread in our lockers, nor wine in our casks; therefore, the reader will not be surprised, if, while he rests, that I should indulge myself with a few of the luxuries of the Port.