Revised Jun 19 2021

← Diary Mar 27, 1850 Home BRODIE Diary Mar 29, 1850 →

Brodie's Pitcairn's Island

Diary, March 28, 1850

March 28th. Fine clear weather, with a light north wind, which increased at noon to a moderate breeze. At daylight we were all on the qui vive, expecting to see the Noble close in to the island; when to our surprise, we found that she was about twenty miles to the northward, still standing to the eastward. On looking at her throught the glass (there being two excellent ones on the island), she appeared to have no foresail, fore-topsail, or fore-top-gallant-sail set, but all her head-sails set. As the sun was shining upon her, we could see her very distinctly. Our observations all agreeing relative to her sails, we came to the conclusion that she must be fishing her sprung fore-yard, or repairing whatever damage she might have sustained on the Sunday, supposing the native report, already mentioned, to have been correct. From her situation, we, of course, assumed her to be the Noble; but from the course she was steering, I thought it probable that she might have had no sail on her foremast yesterday, and that, instead of her sailing towards the island during the night, she had actually drifted so much nearer to us, by makinng lee-way.

As the wind was likely to come from the eastward, I thought she intended to get well to the eastward before she came down to take us on board, as she was in a partially crippled state. At 10 A.M. she was a little to the eastward of the island. At 11 A.M. we all proposed going off to her in whale boats belonging to the island. The islanders would have willingly pulled us out, although to so great a distance, had she showed any inclination to wait for us. But no such inclination was displayed; and as the wind was now increasing, it would have been folly to think of catching her.

At noon the wind veered to the south-east, when she steered to the north-east, and in about an hour was out of sight, leaving us totally unable to account for her proceedings. My own opinion is, that she remained by the island until Tuesday night, when the weather appeared very unsettled, and the captain thinking there was no chance of beating to windward in such a hulk of a vessel, shaped his course for California. But previously, I have no doubt that Mr. Webster (better known as a shopman behind the counter at Gibson and Mitchell's retail store in Auckland) had urged him to ursue this course; at the same time giving him (the captain) an instruction in writing, exonerating him from any blame or expense attending it, thinking that our expenses in getting awayu from the island, &c., &., would be far les than the enormous difference which the detention in trying to make the island might make in the sale of the Noble's cargo—a cargo which was partially perishable. Time, I suppose, will explain everyting. Should this barque not have been the Noble, and the Noble have been drifted to the westward by the easterly winds of Monday and Tuesday last, she had now ample time for regaining her lost ground by the N.N.W. and N. winds, which had been blowing for many hours.

But my firm belief is that the vessel we saw this day was the barque Noble, and that she sttered for California on Tuesday night; and that, after steering some few hours to the northward, she met with the northerly winds, which compelled her to steer to the eastward, when she again came most unwillingly in sight of the island. From her position last night, and also this morning, she must have been close hauled, or nearly so, and must have made about four points lee-way, being a very dull sailer; and having no square sails on her foremast, she must have drifted bodily to leeward during the night. I have no doubt that, at daylight this morning, they were much surprised on board the Noble at seeing their position, but could not prevent our seeing them; and that, as they must have made up their minds to leave us, they did not think it worth their while to come down for us, which would not have detained them three hours, or, at the utmost, four hours. It is possible that they did not imagine that we saw them so clearly as was the case.

Here we were, five of us, left upon an island, without a change of clothes or linen, and not a sixpence in our pockets; but, luckily for us, left, perhaps, with little doubt, upon the most moral and religious island in the world, and amongst the most kind-hearted, hospitable, and generous islanders ever met with.

Hearing that there was another road to the hieroglyphics, rather more circuitous than the one we attempted yesterday in vain, and not of quite so dangerous a nature, Carleton, Adams, and myself made another attempt to reach them Upon arriving at the edge of the precipice, it was an awful-looking place to go down; but, if anything, rather more easy to the eye than the other road. The first hundred yards we slid down in a sitting position, on our haunches, having but little regard for the seat of our trousers, a part of which we expected every moment would leave us. We then came to a place, in my opinion far worse than what we looked at yesterday: it was a ledge of rock, about ten feet long, and of only a few inches in breadth. I must say it made me feel rather nervous; but our guide having told us that it was the worst place we had to cross, I hurried over it as quickly as I could, but with as much caution as possible. Adams persuading us that there was no danger, I did not agree with him. To him it was nothing; he skipped across just like a goat. It is extraordinary to see these islanders go up and down the precipices, and jump from rock to rock, like so many goats. After crossing this bad place, the remainder of our journey down to the sea was still very steep; but, with a few resting-places to recover breath, we reached the sea-shore at last in safety, with no other damage than a few scratches and broken trousers. We then proceeded along the coast for about one-third of a mile. The walking here was very bad, it being over large and loose rocks; fortunately it was low water; or I should have had to swim round a headland that formed one side of the bay—an exercise at which I am not very expert. We now arrived at the spot which had cost us so much trouble and anxiety to reach.

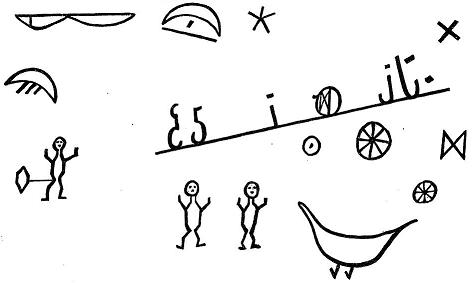

The hieroglyphics were carved at from two to ten feet from the ground, many of them appearing to be nearly obliterated. The rock in which they were cut was exceedingly hard, and much resembled the French burr stone. On the opposite page [below] is an accurate representation of what we saw-the moon, the sun, the stars, a bird, figures of men, &c.;, &c.;

After remaining about an hour, we returned home; not by the same way we came, but by the road which we attempted yesterday, which made a difference of nearly a mile in shortening the distance. Adams took the lead, with a rope and a hoe in his hand, making holes in the ground and soft rock, wherever they could be made to our advantage, in ascending this anything but delightful ascent. When nearly up to the top of the first ridge, I squeezed myself between two rocks to rest, and then requested Adams to pass the rope down to fasten round my waist, as immediately above me the rocks were perpendicular; and having a rope, I thought I might as well make use of it. Adams then hauled, or I should say assisted, me up this difficult pass. Carleton would not use the rope, preferring his own hands and feet to the assistance of others. Upon arriving here, which was the place we looked down upon yesterday, I was most thankful. How curiosity could have tempted me to undertake so dangerous an excursion, I know not; but I do strongly recommend Europeans never to attempt the same for the sake of curiosity. The only strangers that ever attempted and accomplished it besides ourselves were Dr. Domet, Lieutenant M’Leod, and Mr. Lock, of H.M.S. Calypso.

These figures can be visited in a canoe or boat; but only in very fine weather, on account of the great surf running on that side of the island. In the evening there was no appearance of any vessel in sight. I myself gave up all hope of the barque Noble, but the others did not, thinking that she had gone to Elizabeth Island to procure a spar for a fore-yard. Elizabeth, or Henderson’s Island, is about 120 miles from Pitcairn’s—latitude 24° 0′ 2″ south; longitude, 124° 45′ west—is larger than Pitcairn’s, and covered with timber of only a small size, similar to that with which the houses are built upon Pitcairn’s, and which is nearly all used up.

Not long ago, eleven of these islanders, along with John Evans (one of the three resident Europeans), were carried to Henderson’s, or Elizabeth Island, in an American whaling vessel, on an exploring expedition. The landing was any thing but good, and the soil not near so rich as that of their own island, being of a much more sandy nature. Water there appeared to be none; but, after a long search, they found a fresh-water spring below high-water mark. Some cocoa-nuts, which had been purposely carried there, were planted upon the best ground they could find. Several goats had been likewise shipped for turning out, but were actually forgotten until some time after they were returned on board. They were only a few hours on the island, and, therefore, were unable to form or give any detailed description of it.

Elizabeth Island is of a peculiar formation, very few instances of which are known; viz., dead coral, more or less porous, elevated in a flat surface, probably by volcanic agency, to the height of eighty feet. It is five miles in length, one in breadth, and thickly covered with shrubs, which makes it difficult to climb. It was called Henderson’s Island after the captain of the ship Hercules of Calcutta, though first visited by the crew of the Essex, an American whaler, two of whom landed on it after the loss of their ship, and were subsequently taken off by an English whaler, who heard of their fate at Valparaiso. They are very anxious to procure a small vessel or large boat, of about twenty tons burden, to enable them to visit this island at pleasure, and bring off house-timber as required, as likewise to convert it into a run for their live stock; thus relieving their little island from that burden, and enabling them to direct the whole of its capabilities to the use of man. They have established a sort of Bank amongst themselves, in which a large part of the money paid by vessels for refreshments, is suffered to accumulate for the purpose of purchasing a small vessel.