|

|

A GUIDE TOPITCAIRN Published for the Government of the Islands of Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno by the South Pacific Office, Suva.

1963.

|

|

Crown Copyright 1963

Price: Five shillings ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The South Pacific Office, Suva, wishes to thank the following individuals and firms for granting permission to use copyright photographs: G. Allen, pages 7; 22. British Petroleum Co. Ltd., pages 28; 29; 30; 31; 32; 35; 38; 39; 41. J. Christian, pages 8; 15; 19; 23; 24; 33; 40; 42; 43. J. B. Claydon, page 34. Crown Official, pages 17; 25; 37. Metro-Goldwyn Mayer, Cover; page 4. Rob Wright, pages 10; 11; 13; 44; Inside back cover. Prepared for publication by South Pacific Commission Literature Bureau and printed by Bridge Printery Pty Ltd., 117 Reservoir St., Sydney.Page 2 |

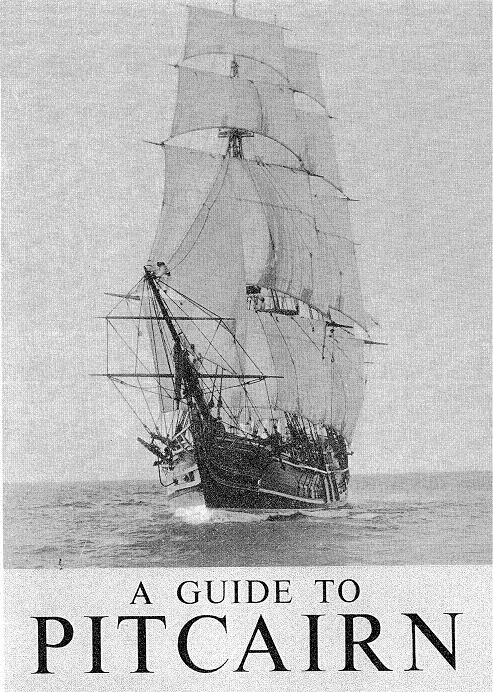

H.M.S. Bounty sails to Tahiti. (Scene from film "Mutiny an the Bounty".)

H.M.S. Bounty sails to Tahiti. (Scene from film "Mutiny an the Bounty".) |

CONTENTS

Page 5

|

|

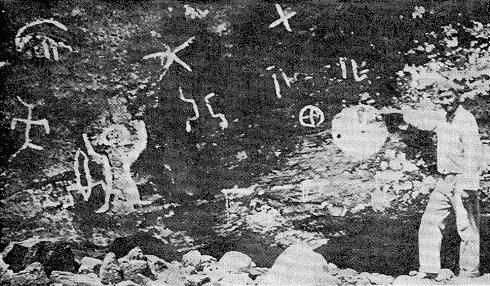

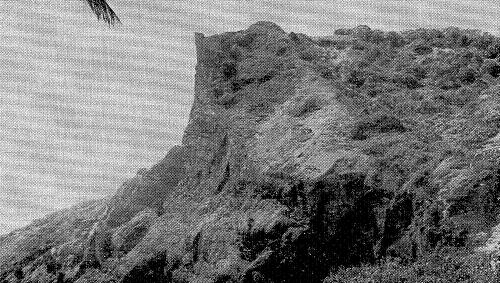

PART IPITCAIRN'S HISTORYAs you sail towards Pitcairn, you approach one of the remotest of the world's inhabited islands, lying half-way between New Zealand and the Americas. Three thousand miles of open ocean separate you from them; a few archipelagos lie to the north; and the southern seas are empty to the ice-caps of Antarctica. If you call at Pitcairn, you will see a unique community of Anglo-Tahitian descent, which turned a naval mutiny into a celebrated romance. Who Were the First Settlers?We do not know who first settled this small, volcanic island about six miles round and two and a half miles at its greatest length. But settlers there were, for early visitors from Europe found many relics of Polynesian civilization, probably from Mangareva some three hundred miles to the north-west. There were roughly- hewn, stone gods still guarding sacred sites; carved in the cliff faces were representations of animals and men; burial sites yielded human skeletons; and there were earth ovens, stone adzes, gouges and other artefacts of Polynesian workmanship.  Polynesian Rock Carvings at Down Rope.

Polynesian Rock Carvings at Down Rope."It is so high that we saw it at a distance of more than fifteen leagues, and it having been discovered by a young gentleman, son to Major Pitcairn of the marines, we called it PITCAIRN'S ISLAND". In these few words were recorded the first sight and naming of Pitcairn by a European. That was in July, 1767, and the words are those of an Englishman, Page 7

|

|

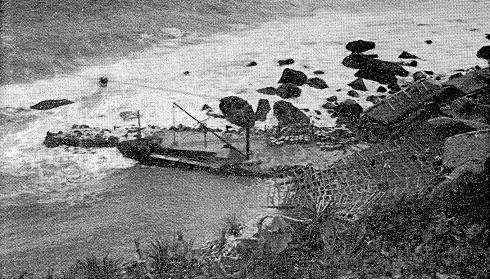

Captain Philip Carteret of H.M.S. Swallow, who was, however, unable to land because of the surf "which at this season broke upon it with great violence". No one except the determined Captain Cook was interested in Carteret's report and his search for the island was deflected by an outbreak of scurvy. So Pitcairn might have become the home of ex-sailors with their Polynesian families and, like other islands in these latitudes, a casual stopover for whalers looking for land and fresh food. But its destiny was to be quite different. The tale of the mutiny on His Majesty's armed ship Bounty, which led to the founding of the Pitcairn community, is well known. All that needs to be told here is that on the 28th April, 1789, when the Bounty was in the Tonga Group on her way home from Tahiti with a cargo of breadfruit trees for planting in the West Indies, the master's mate, Fletcher Christian, and others of the crew mutinied. Casting adrift the Commander, Lieutenant William Bligh, and eighteen loyal officers in the ship's boat, the mutineers sailed the Bounty back to Tahiti, to Tubuai in the Austral Group. There, relations with the inhabitants soon deteriorated and, spurred by the fear of discovery and arrest, nine of the mutineers set sail with Christian in search of an uninhabited island, secure from the outside world. To help them the men took with them six Tahitian men and, to look after them and be their consorts, twelve Tahitian women. Settlement by the Mutineers: 1790For two months the men on the Bounty combed the Cooks, Tonga and the eastern islands of Fiji for a home; and it was almost in desperation that Christian, recalling or stumbling on Carteret's account, sailed eastwards again for Pitcairn, which he reached on the 15th January, 1790. "With a joyful expression such as we had not seen on him for a long time past" Christian returned from the shore to report that the people who had once planted Pitcairn with coconut palms and breadfruit had either died or left it. The island was lonely and inaccessible, uninhabited, fertile and warm; it exceeded his highest hopes.  Ship Landing Point.

Ship Landing Point. |

|

The Bounty was anchored in what is now called Bounty Bay and stripped of all her contents, including pigs, chickens, yams and sweet potatoes, which were 1aboriously hauled up the aptly-named Hill of Difficulty to the Edge, a small, grassy platform overlooking the Bay. Then, fearing that if any European vessel sighted the ship retribution would inevitably follow, the mutineers ran the Bounty ashore and set her on fire so that no trace of her, or clue to their whereabouts, would remain visible from the sea. Fletcher Christian, the man who had led the mutineers to this remote island, was a son of the Coroner of Cumberland and of Manx descent on his father's side. He had been to school with the poet William Wordsworth, was well-educated and, in the words of a friend, "mild, generous and sincere". Certainly his energy and cheerfulness drew both respect and affection from his fellows and, although he died a few years after landing at Pitcairn, he is still remembered as the founder and first leader of the settlement. Of the other mutineers, Midshipman Edward Young was also well-connected and was devoted to Christian whom he succeeded as leader; "reckless Jack" Adams, tater to become patriarch of Pitcairn was a Cockney orphan; Mills, Brown, Martin and Williams were killed within four years of arrival; and of the other two, the Scotsman William McCoy and the Cornishman Matthew Quintal little good can be said, except that they were neither better nor worse than the average seaman of the time. On arrival the mutineers made themselves rough leaf-shelters where the village of Adamstown now stands, but the tiny community did not settle down without friction and, indeed, murder. The Tahitians were treated more as slaves than as fellow human beings and their revolt led to the slaying of some of the mutineers and finally to their own deaths. By 1794 only Young, Adams, Quintal and McCoy remained of the male settlers, leading households of ten women and their children. The next four to five years were peaceful except for occasional outbreaks by the women, including an abortive attempt by some to leave the island. As Young recorded in his Journal: "building their houses, fencing in and cultivating their grounds and catching birds and constructing pits for the purpose of entrapping hogs, which had become very numerous and wild, as well as injurious to the yam crops", kept the settlers busy. Gradually the men and women grew reconciled to their lives and to each other, and all might have remained harmonious had not McCoy, who had once worked in a distillery, discovered how to brew a potent spirit from the roots of the ti plant (Cordyline terminalis). By 1799, Quintal had been killed by Young and Adams in self-defence and McCoy had drowned himself. Then, in 1800, Young died of asthma, leaving John Adams as the sole male survivor of the party that had landed just ten years before. John Adams and His Flock: 1800As leader of the community of ten Polynesian women and twenty-three children the former able-seaman, John Adams, showed himself to be as capable, kind and honest as he had formerly been loyal and helpful to Christian and Young. Each family had its own house and most, but not all, of them were within the village, planned in English style round a common and fenced to keep the chickens in and the hogs out. Solidly built of local timber, some of them with bedrooms on a second floor, the island homes owed little to Polynesia except their thatched roofs. The women had brought their own utensils from Tahiti, which were handed down from mother to daughter, and the men had landed tools and other Page 9

|

|

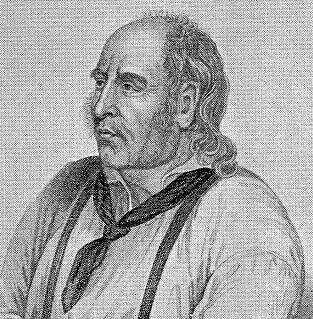

implements from the Bounty and fashioned more as necessary. Food cooked in Polynesian, stone-lined ovens, consisting, mainly of yams, taro and bananas with coconut cream and an occasional pig, bird or goat was, in Polynesian style, served twice a day, at noon and nightfall. Clothes were at first made out of sail-cloth from the Bounty, but they were later replaced by loin-cloths and skirts of tapa, the traditional Polynesian fibre-cloth. In brief, European and Polynesian ways mingled in complete isolation from the rest of the world.  John Adams (from drawing by R. Beechey, engraved by H. Adlard)

John Adams (from drawing by R. Beechey, engraved by H. Adlard)John Adams was no scholar. He read with difficulty and could hardly write, but he was essentially a gentle man who humbly discharged his responsibility for the community he headed. Such was his manner that all took pleasure in obeying his example which he patterned on virtue and piety and regulated by the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer, on Sunday services, family prayers, and grace before and after every meal. And to ensure everybody's well-being, Adams saw to it that the young people cultivated the land, cared for the stock and were not allowed to marry until they could support a family. An End to Isolation: 1808 and 1814In 1808 the little colony was discovered by Captain Mayhew Folger, an American sealing captain, but his visit was brief and his report aroused little interest in an England pre-occupied with the Napoleonic wars. Six more years passed before H.M.S. Briton and Tagis rediscovered the settlement on 17th September, 1814. Ignorant of the American's report, the astonished British commanders were charmed by the physique, simplicity and piety of the islanders. Favourably impressed by Adams and the example he set, they agreed it would be "an act of great cruelty and inhumanity" to arrest him, and so began the long association between Pitcairn and the British Navy which was to influence its development over the next century. Twenty-five years of isolation were now ended. Increasing visits were paid by ships sailing from India and Australia to South America, or to England via the Horn. The reports they brought back stimulated an interest, not least in the English Missionary Societies, and gifts of Bibles, prayer books and spelling books were sent to the island, as well as such practical necessities as crockery, razors, tools and guns. In addition, nearly every visiting ship made generous gifts and bartered surplus stores for provisions, and it was at this time that the orange, now Pitcairn's main export crop, was introduced; that houses were improved with the aid of saws and planes, and clothes and living became more European in character. Page 10 |

|

Successors to John Adams

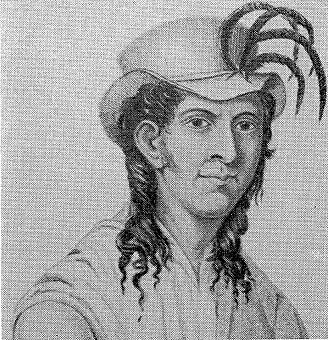

As he grew old, Adams worried about the future of his flock but his appeals to the British Government and missions for a successor to lead and educate them were not met, and it was to voluntary exiles that succession fell. The first was John Buffet, a shipwright from Bristol who landed with John Evans, a Welshman, in 1823. Both married island girls and founded families, and Buffet taught the children and took over the church services. The population had now risen to sixty-six from the thirty-five of seventeen years earlier, and Adams, believing the land was yielding less, seeing the supply of timber decreasing, and concerned that the erratic water supply would be insufficient for the growing population, sought the community's removal to Australia. Meantime, in 1828, another settler arrived. George Nobbs, alleged to be the illegitimate son of a marquis, was well educated and had served both in the British and Chilean Navies. He was a strong character and soon ousted Buffet from the role of schoolmaster and pastor. Then, on 5th March, 1829, John Adams, venerable and corpulent, died at the age of 62. He left behind a community which, though it originated in mutiny and had suffered misery and murder, was to form the basis of countless Victorian sermons. The dramatic regeneration was virtually Adams' work alone, and he was mourned as "Father", the name by which he had been known to every member of the community. Unsuccessful Emigration to Tahiti: 1831Meanwhile Adams' request for emigration was being sympathetically supported in London and, although later naval reports discounted his fears, it was decided to re-establish the islanders in Tahiti. Despite some initial objections, the islanders all set sail on Admiralty vessels in March, 1831. They were given a generous, warm-hearted welcome by the Tahitians but they did not feel at home. They had become on the one hand too European in their ways and, on the other, stricter in moral, particularly in sexual, behaviour than their hosts. They longed to return to their own habits in their own island, all the more so when infectious diseases, to which they had little immunity, began to kill them. In no more than two months eleven of them died, including Fletcher Christian's son, Thursday October, the first child to be born on Pitcairn. Then, assisted by a trader and a missionary fund financed by European subscribers in Tahiti, the islanders bought their passage home. Six months after their removal they were safely back in Pitcairn.  Thursday October Christian (from engraving by H. Adlard. b. October, 1790). Known also as Friday October Christian after 1814 when time was corrected -- see "A Change in Religion: 1887", p. 15.

Thursday October Christian (from engraving by H. Adlard. b. October, 1790). Known also as Friday October Christian after 1814 when time was corrected -- see "A Change in Religion: 1887", p. 15.Page 11

|

|

A Dictator Steps In: 1832

Inevitably the little community had lost some of its innocence. It was leaderless, too, for Nobbs had not yet been accepted as Adams' successor and they could not agree on a local head. There was a period of anarchy and drunkenness but the vacuum was soon filled. In October, 1832, a puritanical busybody, by the name of Joshua Hill, landed on the island claiming to have been sent by the British Government. He was welcomed and, supplanting Nobbs as pastor and teacher, at once appointed himself as President of the "Commonwealth" of Pitcairn. To his credit Hill abolished the distilling of liquor but he also introduced arbitrary imprisonment and other severe punishments for the smallest misdeeds. He secured the expulsion of Nobbs and the other "lousy foreigners" who formed an intimidated Opposition but their departure caused a reaction and his power gradually declined until, in 1838, his claim to represent the British Government was exposed and he was forcibly removed from the island. Nobbs returned from "exile" and by a general vote was reinstated as pastor and teacher. One has only to read Hill's literary effusions to surmise that he was probably mentally unstable throughout his six years on Pitcairn. Pitcairn's First Constitution: 1838The dictatorship of Hill and increasing visits by American whalers brought the islanders to recognize their need for protection, and they prevailed upon Captain Elliott of H.M.S. Fly to draw up a brief constitution and a code of laws selected from those already in force. A Magistrate (who must be native-born) was to be elected annually "by the free votes of every native born on the island, male or female, who shall have attained the age of eighteen years; or of persons who shall have resided five years on the island". He was to be assisted by a Council of two members, one elected and one chosen by himself. Not only was this the first time female suffrage was written into a British Constitution but it also incorporated compulsory schooling for the first time in any British legislation. Whatever the precise legal significance of Captain Elliott's action the Pitcairn Islanders date their formal incorporation into the Empire from the 30th November, 1838, when the new constitution was signed on board the Fly. That they also became a British Settlement later under the British Settlements Act of 1887, is of no consequence to them! A Time of Tranquillity: 1838-1848The next decade was peaceful and uneventful, although in 1845 the worst storm in the island's history destroyed many coconut palms, bananas, yams and boats. Periodic epidemics of influenza; accidents recorded in place-names such as "Where-Tom-Off"; and births, marriages and deaths alone disturbed the placid life. The population topped the hundred mark; Nobbs was firmly in control; and Buffet taught the young men navigation, carpentry and how to fashion curios of the kind still made from Miro and other local woods. Adapting themselves to the needs of their seafaring visitors the islanders became skilled market gardeners, producing potatoes, yams, coconuts, bananas, oranges, limes and chickens for which they accepted in return clothing, tools and money. And largely because they sold their produce for fixed prices, they acquired a reputation for strict honesty. Inevitably the islanders' language, clothes and ways grew more European with these contacts but Tahitian customs were not entirely swamped, and the Page 12 |

|

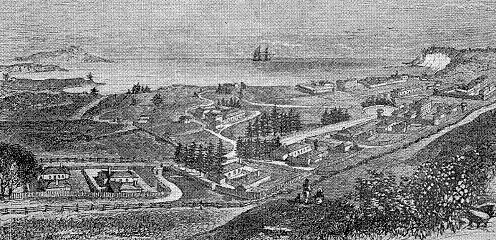

traditional pastimes of kite-flying, stilt-walking and surf-riding still occupied many of their leisure hours. Emigration Again: To Norfolk Island in 1856By 1850 the islanders numbered 156 and were increasing rapidly. Their friends in England and the Pacific were again discussing the question of emigration, for it was feared that land would soon become insufficient and fish had deserted the coastal waters since the landslides caused by the great storm of 1845.  Kingston, Norfolk Island, the residence of the Pitcairn Community, 1857. (From engraving in Murray's Pitcairn.)

Kingston, Norfolk Island, the residence of the Pitcairn Community, 1857. (From engraving in Murray's Pitcairn.)After their experiences in Tahiti the islanders insisted that if they were compelled to emigrate it should be to an uninhabited island, and, after examining several possibilities, the majority of the community decided to move with British Government aid to Norfolk Island. It had much to recommend it. It was larger than Pitcairn and now uninhabited, but sixty earlier years of convict labour had left hundreds of acres under cultivation. It was well stocked with domestic animals; there were roads and houses and, in 1856, when the naval transport Morayshire arrived, all the 194 islanders boarded her. Return to Pitcairn: 1859-1864This might have been the end of the Pit- cairn story, but in spite of the advantages of Norfolk, many of the islanders wanted nothing more than to return home. By this time, no matter who was elected Chief Magistrate, the real leader of the community was George Nobbs, who had been ordained priest in the Church of England in 1852 and who lived on, at Norfolk, until 1884. His early failings had long been for- gotten and, through twenty years of selfless service as spiritual mentor and secular  George Hunn Nobbs (from a daguerreotype by Kilburn, engraved by H. Adlard)

George Hunn Nobbs (from a daguerreotype by Kilburn, engraved by H. Adlard)Page 13

|

|

teacher, he had won affection and trust in his adopted home. Had he opposed migration few of the others would have Bone but not even his arguments against return could conquer nostalgia. Late in 1858 an opportunity arose when the Mary Ann, en route to Tahiti, offered passages and sixteen of the islanders led by Moses and Mayhew Young boarded her. Characteristically, those who chose to stay behind voted to pay the costs of the journey from communal funds. The returned settlers found their houses in Adamstown and their gardens overgrown and the cattle and other domestic animals running wild. And they arrived just in time to stop the French, who thought the island abandoned, from annexing their home. In 1864 a further four families from Norfolk Island decided to return led by Simon Young who, with Nobbs' parting blessing, was to become the community's new Leader. It was a different Pitcairn now, of forty-three people and only five families -- the Youngs, Christians, McCoys, Buffets and the American Warrens. And of these, the male lines of the McCoys and Buffets were to die out! A Swiss Robinson ExistenceThis third wave of settlers knew from past experience how to make the best use of their resources, but materially they were probably worse off than the mutineers. They had, for instance, no sail cloth to turn into clothing and no means of lighting their makeshift homes other than by candlenut. What was more, there were far fewer visiting ships from which to obtain goods. The peak period of whaling in those latitudes was past and, compared with the forty ships a year that called twenty years previously, there were now only about a dozen. The occasional vessel that did stop, however, was now likely to be a steamer carrying passengers. The islanders therefore turned Buffet's lessons to advantage by selling them curios in place of the food they had sold to the whaling crews. Their limited resources were fortunately supplemented by a succession of shipwrecks which brought them a new "bounty" from the outside world. The kindly community fed and clothed the shipwrecked sailors who, after they returned home to relate their adventure, acquitted their rescue with gifts of crockery, clothes, flour, books and even an organ. Renewed visits by men-of-war in the Pacific also revived the traditional English interest in the children of the Bounty mutineers. Queen Victoria sent another Organ as a personal gift in appreciation of the islanders' "domestic virtues"; and a Liverpool firm tried to rouse interest in the commercial production of cotton, arrowroot and candlenut oil. The Islanders Settle DownAs Nobbs had planned, Simon Young took over the work of pastor and schoolteacher and the former system of government by a Magistrate and two councillors was re-introduced. Almost the first communal task was the construction of a combined school and church but, with this, repairs to houses and the replanting of gardens there was no energy left, and much of the island reverted to natural bush. In 1868, some of the Norfolk Island settlers, including old John Buffet, who was to live to the ripe age of ninety-three, visited Pitcairn and urged their relatives to rejoin the now wealthier community. But nothing happened except that occasional visits between the two settlements have continued, desultorily, until today. Page 14 |

Aute Valley and natural bush.

Aute Valley and natural bush.New blood brought new ways and ideas to the tight, little society, but one of the newcomers fell in love with a girl who was, unfortunately, already engaged to a Christian, Strong passions were aroused and the Commander of the visiting H.M.S. Sappho was induced to approve a law forbidding strangers to settle on Pitcairn. The law was later amended but only to permit settlement by those whose presence was considered of benefit to the island. A Change of Religion: 1887With the passing years and no strong leader, reports of social deterioration grew. Simon Young, loved and respected, and his gentle and talented daughter, Rosalind, were too humble and tolerant of frailty to impose their will, and family faction inhibited cohesion. From the days of John Adams, the islanders had been staunch adherents of the Church of England. They read and studied the Bible, which was for many of them their only reading matter, and its texts were truth. Not unnaturally, therefore, they read with increasing interest the contents of a box of Seventh-Day Adventist literature sent to them from the United States in 1876. And when a missionary arrived ten years later he was allowed, by unanimous vote, to stay and argue his cause. The result was recorded in Mary McCoy's diary in March, 1887: "The forms and prayers of the Church of England laid aside. During the past week meetings were held to organize our church service on Sabbath". So Saturday again became the day of rest, as it had been until 1814 when Fletcher Christian's omission to correct the time across the date-line was rectified. Conversion was greeted with great pleasure by the Seventh-Day Adventists in America and they raised funds for a missionary ship which sailed for Pitcairn in Page 15

|

|

1890. The islanders were baptized in one of the rock-bound coastal pools and the pigs were killed to remove the temptation of eating pork. But few other changes were needed; all were already total abstainers; most were vegetarians, except for occasional meals of goat-meat which is not forbidden by Adventist discipline; and few smoked. Parliamentary Government, 1893The Missionaries relieved the aging Simon Young in the school and, energetically, introduced history, grammar, cooking and nursing; began a newspaper and a kindergarten; and opened a public park. Thus stirred by example, the islanders began to question their social inertia and, putting it down to weakness in their leaders, asked Captain Rooke of H.M.S. Champion to reorganize their system of government. An elected Parliament of seven was introduced and, for the only time in Pitcairn's history, executive and judicial functions were separated. The legal code also was revised to create penalties for, amongst other things, adultery, wife-beating, cruelty and "Peeping Toms"; and the system of public work of pre- migration days, was restored. Society was a long way, indeed, from the simple order of Adams! The Influence of James McCoyBut the reports of the naval officers who visited Pitcairn towards the end of the nineteenth century still continued to reveal how society had deteriorated since the return from Norfolk Island. There was lawlessness and a lack of unity and purpose; and, in 1897, murder. That the community did not degenerate still further was due largely to the influence of James Russell McCoy, a great grandson of the mutineer. In 1870, at the early age of twenty-five, McCoy had been elected Magistrate and during the next thirty-seven years he was chief executive no less than twenty-two times. Although island-born, McCoy had spent some time both in London and Liverpool and, autocrat though he was, he was also, in a real sense, a link between the old Pitcairn and the new. By the turn of the century he had restored purpose to the community by enforcing the recently revived laws of public work; and his personal courage and example, which won him respect if not popularity, secured improvement until he began to spend much of his time overseas on missionary work. The Constitution RevertsIn 1904, R. T. Simons, the British Consul at Tahiti, paid his first visit to Pitcairn and found the parliamentary system too cumbersome for the small community. He re-introduced the time-honoured post of Chief Magistrate and two committees to take charge of internal and external, that is marine, affairs. All the posts were made subject to election and an additional office of Secretary- Treasurer was created. What was more, the days of representation without taxation were ended: an annual licence-fee for the possession of firearms was introducd[sic] which, today, is still Pitcairn's only tax. With some amendment Simons' constitution and code stood the test of time until in 1940 H. E. Maude, representing the British High Commissioner in Fiji, consolidated and expanded them. Page 16 |

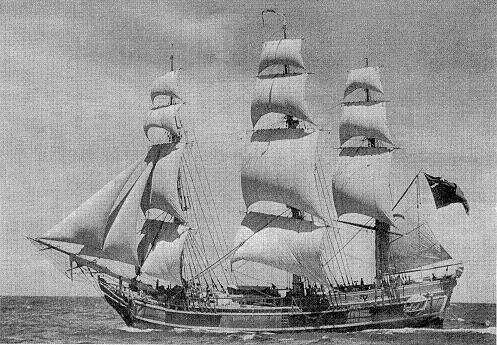

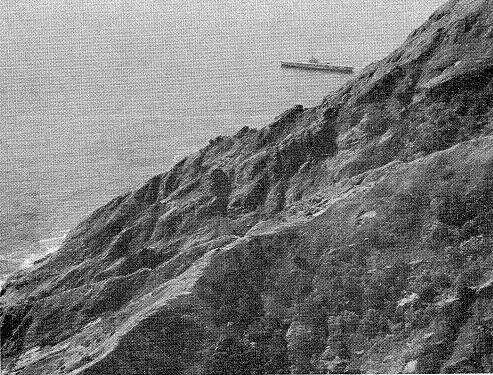

H.M.S. Warrior off Bounty Bay.

H.M.S. Warrior off Bounty Bay.The twentieth century brought an end to European rivalry in the Pacific and naval visits gradually diminished. Fortunately the Mission ship, Pitcairn, and her successors maintained contact with Tahiti and merchantmen again began to call with increasing frequency until, in 1914, the opening of the Panama Canal placed Pitcairn on the direct run to New Zealand. Many of the new visitors were liners carrying hundreds of passengers anxious to have mementoes of the island, half-way rock on the longest, regular service in the world. A ship a week, and Pitcairn's isolation was over! The pattern of life changed, inevitably. More and more men developed an urge to see the world, which money and the visiting ships made possible, and communities grew up in Wellington and Auckland from which some moved on to Australia. But, even so, the public economy of Pitcairn languished and it was not until postage stamps were issued in 1940 and philatelists came to the rescue, that shanty town became the Adamstown of today. Page 17

|

PART IIPITCAIRN AND ITS PEOPLE(From the Unpublished Travels of Richard Shaw Nichols. Circa. 1852). Pitcairn has changed, but much is still the same and this is how it is described in modern terms over a century later by the island's Education Officer:

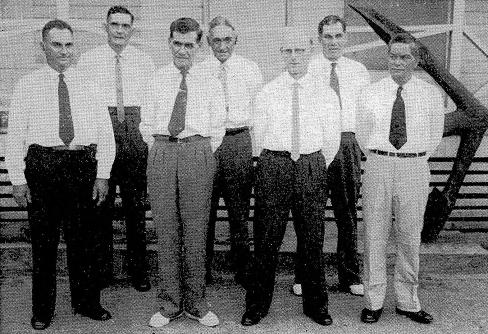

You may feel you would like to settle there; quite frequently inquiries are received from would-be visitors or settlers. But immigation[sic] is controlled (by Ordinance No. 1 of 1954) and a permit to land, other than casually for a few hours, must be obtained from the Governor in Fiji, who exercises his powers in consultation with the Pitcairn Island Council. Since there are absolutely no facilities for visitors, permission to reside is not frequently given. The Pitcairn IslandersAs recounted in Part 1, the people of Pitcairn Island are descended from the mutineers of the Bounty who, led by Fletcher Christian, landed there in 1790 with six Tahitian men, twelve Tahitian women, and an infant girl. The first reliable estimate of the population was given by Captain Folger of the Topaz in 1808 when it was 35, and by 1856, the year of the migration to Norfolk Island, it had increased to 194. By 1864 a total of 43 people had returned to Pitcairn and in 1937 the population reached its peak of 233. Since then it has declined, to remain fairly constant between 130 and 150. The rate of increase over 3 per cent annually in the period 1808 to 1856 and about 2.5 per cent from 1864 to 1937—was quite remarkable at a time when other populations of the Pacific were declining, and it indicates that the original Anglo-Tahitian stock was strong and healthy. Inter-marriage with close relatives has been necessary, but the population has remained tough and vigorous helped, no doubt, by the few immigrants of English and American origin. Contrary to Victorian prognostication that a closed society would deteriorate mentally and physically no evidence of harmful effect has yet been adduced. On the whole the features of the islanders are English, particularly those of the men. In stature Pitcairn Islanders tend to be tall; skin colour varies from a light Polynesian brown to darker than fair; brown to hazel eyes occur more often than blues and greys; and the black hair of Tahitian ancestry predominates. Page 18 |

|

The decline of the resident population from its pre-second-world-war peak of 233 to 126 in 1961 is attributable to migration, principally to New Zealand. The impetus to migrate was the considerable surplus of young men of marriageable age and the attraction to them of improved economic status, particularly during the war years when communications with the outside world were restricted. During the war, too, several islanders served in the armed forces: on land in Germany, the Middle East, the Pacific and South-East Asia; in the air; and at sea with the Merchant Marine. A constant and balanced inward and outward flow of Population has now become part of the order of society, but the island tends to suffer from the loss of men and women in the prime of life, even though the rate of natural increase has recovered since the war. Statistics of the population and its composition are given in Appendix I. CHARACTERISTICS OF PITCAIRNWhere the Island LiesPitcairn is a small volcanic island situated in the South Pacific Ocean at latitude 25°04' south and longitude 130°06' wert. It is roughly 1,350 miles east-south-east of Tahiti; 1,910 miles east by south of Rarotonga in the Cook Islands; 3,320 miles east by south of its administrative headquarters in Fiji; some 3,300 miles east-northeast of Auckland, New Zealand, the southern terminal of its main line of communications; and just over 4,100 miles from Panama, the gateway to the United Kingdom, America and the north-east. It is of irregular shape, some two miles long by a mile wide and, from the best available map, its area is 1,120 acres (1.75 square miles). Physical FeaturesIt is a rugged island of formidable cliffs of reddish-brown and black volcanic rock, nowhere giving easy access from the sea. From Hulianda Ridge just above the landing, at Bounty Bay, round the southeast corner where St. Paul's Point rises lofty and bristling, through Down Rope, with its tiny beach, past Gudgeon to Christian's Point at the western extremity, the cliffs are sheer and inhospitable, capped by volcanic ash and tuff. Many of the land slopes, too, on the western side are very steep, the highest point on Pawala  Pawala Valley and Ridge, rugged and precipitous.

Pawala Valley and Ridge, rugged and precipitous.Page 19

|

|

Valley Ridge, only a few hundred yards from the coast, being 1,100 feet above sea-level. In the north, from cliffs of over 200 feet, the land rises a little less precipitously to about 900 feet; and the slopes of Flatland, which nestles in the centre, run comparatively gently downwards to the north-east and the settlement of Adamstown. In local parlance there are a number of valleys or "walleys", though many are only minor depressions in rock caused by normal weathering. For most of the year they carry no water but, just west of Adamstown, "Brown's Water" is a spring of intermittent flow. The lower slopes and floors of the valleys have soil of colluvial origin and are usually heavily covered with fruit trees. Flat or flattish land forms only 8 per cent (88 acres) of the total surface of Pitcairn; rolling land covers 31 per cent (352 acres); steeply sloping land 34 per cent (385 acres); and cliffs the remaining 27 per cent (293 acres). Geologically, Pitcairn is comparable with other Pacific Islands such as Hawaii, Tahiti and Samoa. It appears to have been formed by progressive volcanic activity and to be the top of a volcano whose base is far below the sea. Only a few hundred feet from the coast there is neither shelf nor coral growth and the rock structure is dominated by basalts with later additions of andesites, trachytes and pyroclastics and minor intrusions of obsidians and pitchstones. The ClimateThe climate of Pitcairn is equable. Although there are no regular trade winds, east to north-east winds predominate with westerly winds increasing in frequency in the winter months. Mean speeds range from 11 to 15 knots and east to southeast gales of short duration may occur perhaps a dozen times a year. Hurricanes have been experienced but are extremely rare. Mean monthly temperatures vary from around 66°F. in August to 75°F. in February, and the absolute range recorded is 51° to 93°F. The rainfall average for the period 1956-60 was 81 inches annually which was fairly evenly spread throughout the year, July and August being the driest months and November the wettest. Relative humidity is usually upwards of 80 per cent and cloud averages six-tenths. VegetationThe natural forest observed by Carteret at the time of Pitcairn's discovery in 1767 has almost vanished and the island is now covered with secondary bush and grassland. The bush consists of small trees, burau (Hibiscus tiliaceus); tapau (Broussonetia papyrifera); rose apple (Syzygium jambos); guava (Psidittm guajava) and tall weeds such as lantana (Lantana camara). Local tradition has it that there were few or no native grasses on the island originally. Today the most common species are Alwyn Grass (Sorghum halepense); cat's-tail (Sporobolus elongatus); Job's tears (Coix lacryma-jobi); crow's foot (Eleusine indica); and paspalum (Paspalum orbiculare and P. conjugatum). The more important of the large number of plants and trees that have been introduced are referred to on p. 25; and, in general, most of the common tropical and sub-tropical plants are now present. Animals and BirdsThe only native mammal is the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans); and cats, dogs, goats, fowl and the common mouse have been introduced, the mouse as late, it is said, as 1942. The Register Book records that rabbits and cattle were landed in Page 20 |

|

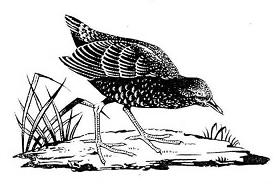

1849 but they did not survive; and the common pig was exterminated towards the end of the last century when the island was converted to the Seventh-Day Adventist religion. An interesting and rare introduction is the Galapagos giant tortoise, (Testudo elephantopus). However it does not breed -- possibly because the two or three are all of one sex. The birds of Pitcairn are predominantly oceanic and migrant, the few land birds having affinities with those of the Austral and Tuamotu islands in French Polynesia. Of twenty-eight types listed, Henderson Island (see p. 45) has seventeen including the unique, flightless chicken-bird (Nesophylax ater); Oeno thirteen; Ducie ten and Pitcairn six. There is no record of the extinction of any native species. Of the birds breeding on Pitcairn the best known are the Fairy Tern (Gygis alba pacifica), the Common Noddy (Anous stolidus pileatus) and the Red-tailed Tropic Bird (Phaethon rubicauda). The Pitcairn Island Warbler (Acrocephalus vaughani vaughani) or "sparrow", is a native subspecies, dark brown above and yellowish to buff below. Legislation has been enacted to protect the bird-life.  The unique and flightless Henderson Island Chicken-Bird, from a drawing by Farrar Bell.

The unique and flightless Henderson Island Chicken-Bird, from a drawing by Farrar Bell.ADAMSTOWN AND THE NEIGHBOURHOODThe threshold of Pitcairn is a rutted path set with rough stone steps. Running from Bounty Bay to the Edge—the level grassy area at the top of the cliff—it follows the track used by the mutineers when they landed. It rises sharply upwards for 200 feet, hugging the side of the reddish cliff, slippery in the rain and hard and gravelly when it is dry. And as in the days of the mutineers certain goods must still be carried up this path if they are too heavy for the flying-fox that the islanders now possess. The settlement of Adamstown, the original home of the mutineers, is well situated on a northerly slope 400 to 500 feet above sea-level, and covers some sixty acres of park-like land. The main path from the Edge, above the landing at Bounty Bay, runs for about half a mile through the village roughly parallel with  On the main road.

On the main road.Page 21

|

|

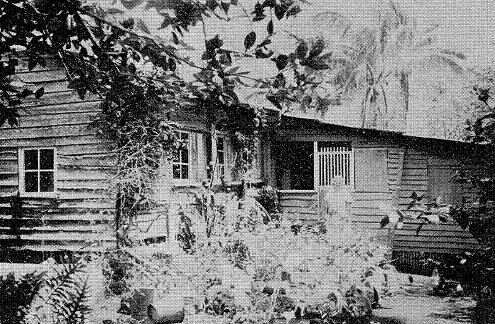

the coast. "Upside" and "downside" of the path numerous little lanes wind towards sprawling houses, scattered irregularly among bushes, ornamental shrubs and garden patches. There are some seventy houses in Adamstown, mostly one-storied, and although 60 of them are classified as being in a state of good repair it is improbable that many more than half will be occupied at a time.  Thursday October Christian's house, the oldest home on the Island.

Thursday October Christian's house, the oldest home on the Island.Built on simple foundations of boulders and logs or wooden piles, with floors of roughly-dressed boards, the houses are well-ventilated at ground-level. The weather-board walls are often unpainted and, although most of the windows are now glazed, sliding shutters of an original pattern, which enable the whole window space to be used for ventilation, are still to be seen. All the roofs are of corrugated iron from which guttering and pipes lead rain water, the only constant source of fresh water available, into private storage tanks. Kitchens and toilets, and often the bathrooms and workshops as well, are usually separate from the living quarters. In a highly individual society it is not easy to give a pen-picture of average living conditions, but spaciousness is the genera I rule. The average number of rooms in a house is five and the inhabitants three. Kitchens tend to have traditional dirt-floors with a stone oven, an open-hearth fire called the "bolt" and a minimum of furniture; but some are modern, equipped with refrigerators and washing-machines. In the living rooms and on the verandahs there are the usual tables, benches, chairs and a bunk or settee; almost invariably a clock, a telephone and a sewing- machine; and frequently a radio, gramophone, piano or harmonium, and a type- writer. Most of the main bedrooms are furnished with a wooden bed with mattress, wardrobe, sea-chest or chest-of-drawers, and dressing-table. Some of these rooms may be painted; all are spotlessly clean and decorated with soft furnishings Page 22 |

|

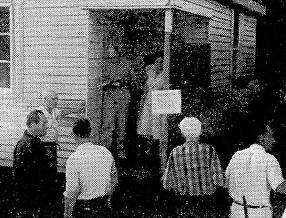

and a miscellany of pictures; and some are lighted with electric light from private plants.  Public Square and Court House with Bounty Anchor outside.

Public Square and Court House with Bounty Anchor outside.The Public Square, "upside" the main path and rather less than half a mile from the Edge, is the heart of Pitcairn. The Court House, a one-storeyed, timber building with a verandah running along its entire length takes up one side of the square and outside, on a plinth, stands one of the anchors of H.M.S. Bounty, recovered by the Yankee in 1957. At one end of the Court House is the Museum and the Chief Magistrate's Office. The main half, rarely used for judicial proceedings, is also the Committee room for the Island Council and the meeting ball for the community. Some thirty yards across the square and separated from the Court House by a strip of garden is the Church, a trim, modern building of concrete and wood erected in 1954, where the Bounty Bible, which is on permanent loan to Pitcairn from the Connecticut Historical Society, is safely kept beside the pulpit. Outside the Church is the bell which is rung both on religious and secular occasions. A series of solemn strikes in ones and twos is the call to prayer; strikes of three summon the able-bodied men to public work; four is the Signal for a share-out of food from a passing ship; and on the strike of live, announcing the arrival of a ship, everyone downs tools and hastens to the landing. On the third side of the square is a new building containing the Dispensary, Library and Post Office and facing it, alongside the path, is a long bench where one may wait for church or assembly or just sit and idly gossip. Between half and three-quarters of a mile to the north-west of the square, along the path to Pulau, are the School and the residence of the headmaster, both of which are modern buildings completed in 1950. Although not strictly speaking part of Adamstown, these two buildings, except for the Radio Station on Taro Ground in the south, complete the record of habitation on Pitcairn; they are magnificently situated among a parkland of natural bush, Brass and coconuts under the shadow of Lookout Point and the yawning cave to which Fletcher Christian is reputed to have repaired in solitude to survey his Island domain. Page 23

|

EARNING A LIVINGThe economy of Pitcairn falls into two distinct parts. The private economy depends almost exclusively on subsistence farming and trading; the public on income from the the[sic] sale of stamps and on interest from investments. A program of social and economic improvement is being undertaken but, because of the island's isolation and small population, economic prospects are restricted; and it is doubtful that much more can be done than to improve subsistence agriculture, introduce minor cash crops and systematize the trade in handicrafts. Mineral resources have not been scientifically investigated, but even were workable deposits of, say, phosphate found, the consequent bounty would be of short-term value and would not ultimately affect the island's future as an isolated coastal community. On an average a man will spend about one day a week in his garden; one day fishing; one day visiting ships and trading aboard them, or getting fruit and vegetables for sale or exchange or attending the boats; part of a day on public work; two days making souvenirs for sale; and the Sabbath at Church and at rest. Occasionally there is the chance of paid labour on government jobs, but it usually provides work only for a small number of men for a few days or weeks at a time. All the women do some form of weaving in addition to their household duties.  Taking home the wood.

Taking home the wood.Wages are normally paid by government only. The current hourly rate is 2s. 6d., there being no differentiation between skilled and unskilled labour. Local government officials are paid allowances, for none of their occupations are full-time, ranging from £30 a year for the Assessors, whose services are rarely required more than twice or three times a month, to £195 a year for the Chief Magistrate. As is common in small and isolated communities, public appointments and the benefits from them are more widely distributed than is warranted by the work to be done. Since the economy of the island is basically subsistence agriculture and there is no retail trading, no price Index is maintained. Imports of food come mainly from passing ships and much of the island's non-consumable stores are purchased through the agents of the New Zealand Shipping Company, Messrs. Duncan Wallet and Company of London, or the Government Agents in New Zealand, Messrs. Burns, Philp and Company Limited, and are often transported free of freight. Clothing is plentiful and costs little in terms of money since parcels continue to come from well-wishers in all parts of the world. Late in 1959, for instance, 17 bales of used clothing in good condition arrived from the United States of America, some of which was sent on to Easter Island which had suffered heavy winds and seas. The principal imports are textiles, flour, canned and dried goods, sugar and fuel. Page 24 |

|

It is estimated that some 60 per cent of the island's souvenirs used to be sold an board ships and the remaining 4() per cent by mail order, mainly to the United States; but, since the passenger liners of the New Zealand Shipping Company ceased to call in 1962, the pattern of trade has been changing and a search for new outlets has become necessary. No assessment of private income that can be considered accurate has been made, for the islanders are reticent about their earnings. But a soil and climate that yield food liberally; generous friends overseas; trading aboard ships and by mail; no taxation; and a tolerant New Zealand which allows access and work without impediment are the Pitcairners' inheritance: and there has been no need so far to reduce it to equivocal statistics. AgricultureWhen Carteret sighted the island in 1767 he reported that it was almost exclusively covered with trees, but settlement and the consequent clearing and burning have left but a remnant of the original forest at the western tip of the island. It is probable that Miro (Thespesia populnea) and Rata (Metrosideros villosa which provides useful timber for building and woodcarving, were original species, but apart from exotics of mainly ornamental varieties, most of the island is now under secondary bush and Brass, interspersed with gardens and fruit trees. Generations of haphazard husbandry, which has encouraged serious erosion in some areas, are not quickly rectified, but quiet steps have been taken since 1960 towards the regeneration of forests by the local government's agriculturalist who was trained in Fiji in 1959-60. Before the scale of afforestation can be increased, however, the predatory goats of Pitcairn must be brought under control, and legislation to that end was approved by the Island Council and enacted in 1960. Soil formation and development is rapid and, although there is evidence of appreciable leaching, the prevalence of nutrient-rich rocks ensures a latent fertility that improved husbandry could exploit. The organic content is low but may readily be improved by green manuring, mulching, composting and possibly the  Bush and gardens near Adamstown.

Bush and gardens near Adamstown.Page 25

|

|

use of nitrogen and potassium fertilisers combined with a rational process of strip bush-fallowing. Most of the gardens lie in an arc on the more gentle slopes to the north and west of Adamstown and provide a variety of root and green vegetables and fruit. Sweet potaoes[sic] (kumara), yams, arrowroot and taro are the staple subsistence foods, supplemented by beans of different sorts, sweet-corn, tomatoes and carrots. Scattered all over the island are bananas, lemons, limes, oranges and grapefruit, all of which flourish and fruit heavily even though cultivation is minimal. Among other produce, mangoes, pineapples, sugar-cane and several types of passion fruit give almost as good a yield, while coconuts of the dwarf species, which were introduced from Fiji some ten years ago, are better suited to the climate than the original tau l varieties. In brief, Pitcairn Island is remarkably fertile and productive. The Allocation of LandLand is held under a system of family ownership, based upon the original division of the island by Fletcher Christian and his companions, and modified after the return from Norfolk Island. Since the system has never been studied in detail it is impossible to decide whether theory differs from practice and the remarks that follow are a synthesis of observers' reports. There is reason to think that the first of the few islanders who returned to Pitcairn from Norfolk in 1859 assumed title to as much of the best land as the pre-emigration system and public opinion permitted. After 1864 there was still some land left in trust for others who never returned and gradually it was incorporated into family holdings. Through these factors and prudent marriages, under a system of bilateral inheritance by which a wife's land passes to her husband, the pattern of ownership has become uneven, but the complaints that are voiced from time to time are more likely to be inspired by resentment of inequality than by actual want. Nevertheless, the pattern of agriculture and settlement places a premium on flattish, fertile land close to Adamstown and in it, and a system known as "borrowing" has been developed to meet scarcity, under which an owner grants usufructuary rights to the borrower, for food gardens or for housing, for as long as he remains on Pitcairn. Bilateral inheritance, although partly balanced by the passing of a woman's title on marriage to her husband, has caused fragmentation and the pattern of usage is one of widely separated plots. A count made several years ago disclosed that there were over 150 garden plots, varying in size from a fifth to a third of an acre, cultivated by 37 families. The pattern today is probably little changed but, as an official soil survey in 1957 disclosed that over live times that area of land was suitable for development as gardens, it is likely that choice plays some part in the patchwork. Legislation concerning land is limited to a simple regulation requiring the Chief Magistrate to ensure that land marks are inspected annually. Although legislation does not prohibit the alienation of land to foreigners, as a general rule the only rights to pass are to their descendants from marriage to a Pitcairner, who acquire the normal benefit of inheritance. At some time the system of tenure will have to be examined, but while the population remains static through emigration time does not press. It is, perhaps, more important that the land under grass and scrub should be brought under Page 26 |

|

forest first, that erosion may be checked and the natural Vegetation restored more approximately to the state it was in when Midshipman Pitcairn first sighted the island in 1767. Animal HusbandryThe only two useful animals are the fowl and goat, but neither is domesticated. The goats, of which there were 156 in the middle of 1961 and only 58 at the end of 1962, are a contentious problem. They are not eaten very often; they are not milked; and they occasionally damage food gardens. But the principal case against them is that by eating bushes, young trees and grass they have contributed to pockets of soil erosion and inhibit conservation and the regeneration of forest. Against this catalogue of criticism stands a body of islanders who regard the goats as a reserve stock of food for emergencies, and legislation enacted in 1960, to secure more effective control and the reduction of goats, was designed to meet both points of view. Whether it will succeed entirely is still in doubt, but the goat defenders realize it serves notice on them and that, if it fails, the elimination of the goats must inevitably follow. As an alternative to goats consideration has been given to re-introducing cattle, but the lack of surface water and of interest in animal husbandry generally makes success problematical. FishingFish, of which the most common are rock-cod, grey mullet, red snapper and a species of mackerel, are plentiful in the seas around Pitcairn but its rocky coastline is often pounded by ocean rollers, and there may be weeks of rough weather when deep-sea fishing is impossible. From the rocks with a line, or about them with a toddling iron (spear), small fish can be caught at almost any season and no fish, however small, is returned to the water. Line fishing from a canoe, kneeling and watching for prey through a glass-bottomed cylinder is traditional, and on a good day fifty to a hundred fish averaging between one and three pounds can be caught. From June to August migratory whales may be seen off-shore and a few months later barracouta may be speared and tuna hooked. On visits to Oeno Island (see p. 46), where the lagoon is rich in tropical fish, large quantities are caught, salted and taken back to Pitcairn. For religious reasons shellfish are not eaten. HandicraftsNearly every household on Pitcairn is a small factory and the whole family takes part in manufacturing handicrafts or curios, a development assisted by Laeffler, an Austrian wood-carver, who lived on the island earlier in this century. The basic work of wood-carving is done in the home workshop with its bench and lathe, and with gouges, chisels and planes which are usually of good quality, The men can often be seen about the island with their baskets containing, perhaps, a partly carved flying-fish and the oddments of small tools and bits they need to complete it. The women's role is the weaving of baskets and hats from pandanus leaf and painting shells and other small articles, all of a type that is widespread in the Pacific. Miro (Thespesia populnea), a dark, durable and handsomely grained wood, is preferred for carving and, since Pitcairn itself has long been denuded, visits for supplies to Henderson Island, one hundred miles to the north (see p. 45), are made when opportunity offers, usually when the Master of a passing ship will Page 27

|

|

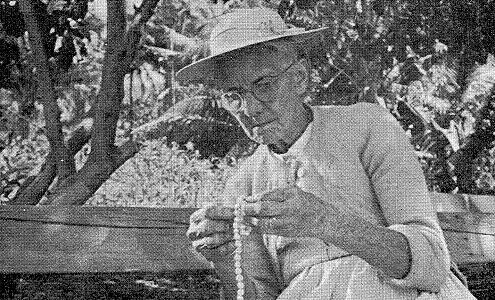

carry the islanders' boats which are later sailed home in convoy. The most common articles carved are flying-fish, tortoises, vases, walking sticks, inlaid boxes and, of course, models of clippers and, more rarely, of H.M.S. Bounty, most of which are sold or bartered on board ships.  Mr. Tom Christian, Senior Wireless Operator, carving a flying-fish.

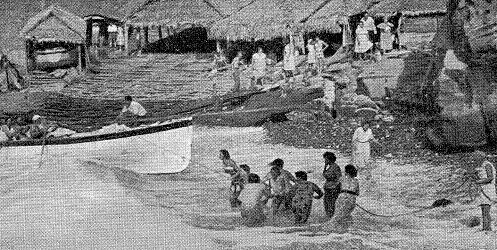

Mr. Tom Christian, Senior Wireless Operator, carving a flying-fish.There is little reliable information about how much is obtained from "trading", but one observer has reported that "the people always say, the money is in those ships so long as you have the curios to trade". Whatever the return is, and it is counted in goods as well as money, it is not negligible. Five strokes of the public bell announce that a ship has been sighted and whatever is being done is at once dropped, fruit and curios are hastily gathered, the boats are launched and manned and plunge out through the surf of Bounty Bay. Apart from the "public fruit" which is exchanged for goods of approximately equal value that are later distributed evenly at the "share out" in the square, it is each for himself on board, and the men stand short watches in the boats below in strict rotation. Trading relations with ship's complements vary according to company policies and personal attitudes, but the romance of Pitcairn rarely leads to the islanders being disappointed. On passenger liners, however, the pattern is always much the same: trading starts when the deck is reached; the men sell what they can as quickly as possible and disappear below to contact their "friends"; the women remain on deck and in the foyers to go on with their trading and are always ready to answer the many questions fired at them. Usually the call is enjoyed by everyone and when Page 28 |

A share-out in the Public Square.

A share-out in the Public Square.the ship's siren sounds, hands are shaken, the islanders clamber down the ladder and, as they pull away, burst into a song of farewell that competes with the churning propellers. The Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy, in recent years the latter in particular, have had a long and generous connexion with Pitcairn and it is fitting to pay tribute to them for, if these ships did not call on the long haul between Panama and New Zealand, it might well have been necessary to abandon the island. Ships and the sea are not only part of Pitcairn's history, they are also its continuing lifeline, providing the means of living, of contact with the far-off world and, sometimes, even of life itself for a dangerously-ill islander. Public Finance and PlanningThe £ sterling is used for keeping Pitcairn's accounts; the £ New Zealand is in general circulation; and American and other currencies can usually be exchanged on the island. British postal orders are sold and cashed and travellers' cheques are accepted. The public revenue of Pitcairn comes almost exclusively from the sale of postage stamps and interest on investments; and except for minor licences, there is no taxation. Financial administration is vested in the Governor, but all local expenditure is estimated and controlled by the Chief Magistrate in Council. The island's revenue and expenditure from 1957 to 1962 were as follows:

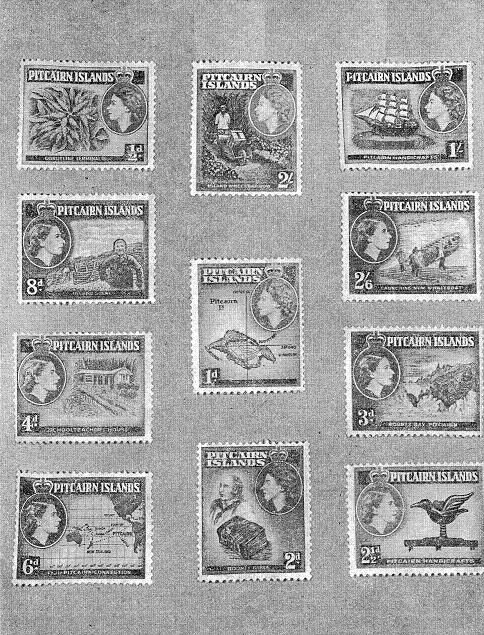

Further details are given in Appendix II. The sale of stamps was introduced in 1940 as a means of financing development, and it can truly be said that stamps bunt the island school. Page 29

|

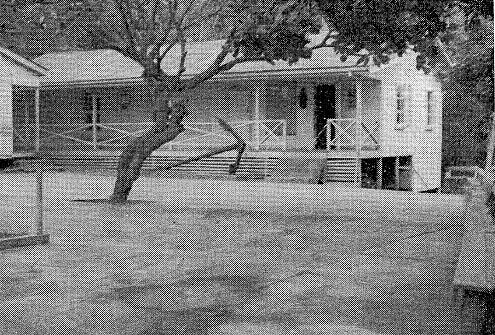

Bounty Bay with facilities partly completed.

Bounty Bay with facilities partly completed.The practicability of developing Pitcairn's resources is very limited and assistance from Britain under the Colonial Development and Welfare Acts has so far concentrated an communications and agriculture. In 1958 a development plan was approved by the Island Council and Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom which provided for the improvement of landing facilities in Bounty Bay, a new radio installation, agricultural surveys and training, and technical training overseas. The programme is still under way and between 1958 and March, 1962—the following grants had been approved for work accomplished:

From the introduction of the plan in 1958, Pitcairn has contributed 10 per cent of the cost of development expenditure which is not included in the preceding table. Attempts have been made to interest the islanders in savings-bank facilities but with no success so far. COMMUNITY LIFE AND LEISUREPitcairn is a family of individuals, and community life and leisure reflect it. Public WorkPublic work which, by law, is required of all men between the ages of 16 and 60 is partly a relic of the homogeneous community created by John Adams and Page 30 |

|

partly a necessity born of the basically moneyless economy. The duties included in it are all decreed and controlled by the Internal Committee on behalf of the Island Council, and in recent years that part which is not traditional has been reduced as far as finance reasonably permits. Nowadays there is a government school which provides free education; there are government-provided radio communications which benefit the private citizen as much as the administration; there are public buildings which house a free dispensing service for the sick, a post office, a library and a combined Court House and community hall. These are all services which fall outside the old tradition, and public work on them is kept to a minimum.  Manning the boats.

Manning the boats.Perhaps the most essential of the public duties that are still recognised as being traditional are concerned with Bounty Bay and the maintenance of the public boats, which are public in the sense that they are owned by the community and not by the government. Installations in the Bay, however, are provided mainly from general revenue and grants from Britain and, since they are vital to the life of the people and the outcome of older custom, there exists a degree of give and take in their maintenance. Public trading, the landing of cargo, the "share out", and the maintenance of roads and paths are also part of accepted community service as, in very much the same category, is the voluntary work undertaken for the Church. There is little doubt, however, that public work is generally unpopular on Pitcairn as it would be in much of the rest of the world; but it is all too evident that a small community, so dependent on co-operative action, could not change over entirely to a system of paid labour, so the grumbles and compromises are likely to go on as they have always done. The ChurchThe Seventh-Day Adventist Church which established itself on the island seventy years ago is attended by most of the population though, from time to time, a teenage group led by some modern mutineer chooses to assert its independence by refusing to attend services. The Sabbath School meets at 10 o'clock on Saturday mornings, the Seventh Day Sabbath, and is followed by Page 31

|

A Church Service.

A Church Service.Divine Service an hour later; an Tuesday evenings there is a further service in the form of a prayer meeting. A Young People's Society, which aims at providing for the spiritual and social needs of youth, meets for divine service weekly and for social recreation once fortnightly; and a junior society provides for young boys and girls in a similar way. Local administration of the church is vested in a resident Pastor and elders, and it forms a branch of the Central Pacific Union with headquarters at Suva in Fiji. FilmsFilms are very popular and regular supplies are received from the British Government's Overseas Film Library in London; from the Fiji Branch of the British Council; from the National Film Library of New Zealand; and, through the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, from the United States. Commercial films are also hired occasionally from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in New Zealand and when they are shown a Charge is made to cover the cost of hiring. The Island NewspaperIn April, 1959, the Education Officer and Pastor published the third monthly news-sheet in Pitcairn's history -- Pitcairn Miscellany. Its predecessors were The Monthly Pitcairner, which was born in December, 1892, and about which little information is available; and Pitcairn Pilhi which, published also by an Education Officer, ran from July, 1956, to December, 1957. In its own words Miscellany sets out to publish "highlights of overseas news, local news, ship news, entertainment news, Church news, and any other features that come to the notice of your editors and which are thought likely to interest you". Hardly an issue fails to contain contributions by the islanders, and not least valuable are their occasional reminiscences and interpretations of the earlier history of the island. The circulation of Miscellany is uncertain, but letters have appeared in it from England, South Australia, Texas, Ontario, and East and West Germany. Page 32 |

|

Clubs and Community Recreation

In 1956, Clubs both for men and women were formed with guidance from the Education Officer. They tend to be spasmodic in activity but their meetings provide a useful forum for discussing community affairs, and a committee of the Men's Club is responsible for organizing Sports and entertainments. Community recreation is not, however, deeply rooted in the Island, partly because of the individual character of the people and partly, perhaps, because an active, outdoor life during the day tends to send people early to bed unless there is a special incentive to break routine. During the summer months the children play in Bounty Bay and the young men may be seen shooting the breakers on surf boards; occasional picnics are arranged, particularly when the yams are ready to harvest in April and May; fishing and goat-hunting interest many of the men; women drift into groups to weave their baskets and gossip; and the square at Adamstown provides shaded benches for the old and the idlers, and an open space for the young to play in. Church and church societies, the occasion u meeting, the odd evening of table-tennis or other games, perhaps an annual concert and fancy-dress party for the children, the ever popular films, and the recurrent birthday parties are the complement of the day-time work of the community.  A Christmas tree on the Public Square.

A Christmas tree on the Public Square.Cricket on Pitcairn deserves special mention because the traditional matches are played in a pre-Hambledon spirit. A word is spoken, the challenge taken; deliberation develops into argument and by evening teams of a score or more a side are announced. Old bats are brought out, new bats are hurriedly made, the miscellany of other equipment is inspected and repaired; and at daybreak the public bell rapidly tolls the way to the hillside -- "up Hulianda" or to "Number Seven" -- where the young men armed with hoes and cane knives soon clean a pitch in the Alwyn grass and cat's-tail. When enough stragglers have arrived, straws are drawn to see which side bats Page 33

|

|

first, scorers from each are Chosen to ensure a degree of unanimity and mathematical accuracy in the tally of runs, and the game begins. There is no batting order: men and boys push and grab and the victors, flourishing their bats, take up stance at the crease, surrounded on the leg side by their own team impatiently waiting for the Chance to push and _grab again. There is no controversy about unfair Bowling which, fast, erratic and- sometimes alarming, is from the "up-side" end of the pitch. The prevailing stroke is a hearty and lofted sweep to mid-on, for the grass, scrub and hillside pitch make other strokes almost worthless, and the ball is enthusiastically chased by all fielders within rang,e, and by a good number of excited children as well when it vanishes into Alwyn grass and Lantana scrub. Occasionally, unless the precaution of burning-off has been taken, these forays into the grass are hotly resented by wasps which turn the vigorous pursuit of the ball into a tactical manoeuvre of beating, Barts and dashes! Nom the edge of the grass a constant wave of barracking breaks over the field, rising to cheers when the ball is lost or a wicket falls, and to mild ribaldry when an unfortunate batsman collects a "duck".  Cricket at "Up Hulianda".

Cricket at "Up Hulianda".Quiet falls at breakfast time, the Pitcairn equivalent of the luncheon Break, but only for a few minutes, for the younger men are anxious to return to the battle which continues until the sun dips below Taro Ground. By then, each side will have batted up to seven times, some eight hundred runs will have been agreed and recorded by the rival scorers, and tired but triumphant the winners will throw down a challenge for tomorrow with a public dinner as the stake. During the night the opposing captains are surreptitiously at work to ensure that when the game is resumed next morning, every family will have representatives on both sides, Who wins or loses on the second day is then less important; the end has been achieved for every family will be involved in preparing the public dinner. And so the contest comes to its Brand finale in the riot of a women's game and the good-fellowship of a public feast. A Birthday FeastIt is on occasions such as birthdays, not necessarily held exactly on the date, that the controversial goats come into their own, if one may so describe the hunt that ends with several of them in the stone oven along with some of the local variety of chicken. Page 34 |

Preparing "Pillhai"

Preparing "Pillhai"All of the closest relatives, perhaps a third of the island's population, are invited to "tea" and around the long table, neatly laid and covered with a cloth, an array of chairs and benches await the guests, who come laden with their own pillhai, a mixed vegetable dish, and, from those who have refrigerators, jellies and cold puddings of various kinds. Everyone is seated and grace is said—probably "Bless this food kind Father, bless it to our soul's use and make us thankful. Amen"—and silence is broken only as the feast advances. The Pitcairners are solid trenchermen with a taste for sweet delicacies which they mix appreciatively with meats and vegetables an the single plate that serves throughout the meal. Conversation about the food and the capacities of the eaters begins to flow and complimentary belching brings a glow of satisfaction to the hostess, who bustles from oven and "bolt" (open fire) and washing-up to the table with yet more food and steaming cups of cocoa and brav tea. This Pitcairn is a "dry" island, but then its early years were clouded with the murders and miseries that followed William McCoy's conversion of a Bounty Boiler into a still for procuring spirits from the roots of the ti tree (Cordyline terrninalis). When the guests have had their fill and every "bally" is tight, they drift off to the verandahs to continue their convivial talk while the helpers take their turn at the table and the young children receive attention if they need it. For a short while, hosts and helpers mix with the guests and the conversation, still mainly of the feast just finished, drifts into somnolence. The party slowly breaks up with a minimum of acknowledgement, that speaks for the unity of the family, and with a parcel of tit-bits and bones for the patient dogs. "So long as you get enough" is the host's farewell and no Pitcairner would be so churlish as not to have eaten up to it! Page 35

|

EDUCATIONThe Pitcairn DialectThe dialect of Pitcairn is a mixture of English and Tahitian, with the former naturally predominating as most of the island's contact is with the Englishspeaking world and education is in English. With visitors a softly slurred English is spoken which is perfectly comprehensible, but among themselves the islanders tend to lapse into a dialect which at times is hard to understand. Apart from the two tongues that came to Pitcairn when it was settled in 1790, a local idiom, particularly in place names, which is pari of the island's history, has developed so that a conversation may be studded with bewildering references to John Catch a Cow; Where Tom Off; Father's Block; Timiti's Crack; Up in Ti; Six Feet; and Jinny's Bread. Some of the more common phrases in use, which give an idea of the form of dialect, are:

The story of education on Pitcairn Island was begun by John Adams in the early years of the nineteenth century when, from the Bounty Bible and a prayerbook, he taucht the first generation of children to read. In 1823 John Buffet, a volunteer off a whaling ship, remained behind as instructor and in 1828 he was joined by George Hunn Nobbs who assumed the triple röle of pastor, surgeon and teacher, first on Pitcairn and later on Norfolk Island. After the return from Norfolk Island in 1864, Simon Young, a descendant of one of the mutineers, and his daughter Rosalind kept a simple education alive until, in the last decade of the century, the school came under the guidance of the Seventh Day Adventist Church. Between 1917 and 1938, when the Church again appointed a resident pastor, the academic side of the school was once again left to the islanders. In 1948 Government formally assumed responsibility. The Education Officer, as he is commonly called, is appointed by the Governor in consultation with the New Zealand Department of Education which, except during 1958 and 1959, has courteously made available the services of qualified teachers for tours of duty of two years. In the management of the school the Education Officer is assisted by a committee consisting of the Chief Magistrate as Chairman, and two members appointed by the Island Council and the Island Church. Legislation, first introduced in 1838, provides for the compulsory attendance of children between the altes of 5 and 15 and for a minimum five-hour day for 380 half-days a year. The timetable has to be approved by the Governor of Fiji. Examinations are conducted by the Education Officer and the Governor may prescribe external examinations and arrange for inspection. The school and the teacher's residence are of timber and iron construction and were completed in 1950. The equipment is modern and includes a 240v. lighting plant, a film projector, and some apparatus for technical training. The school library is kept well stocked. Page 36 |

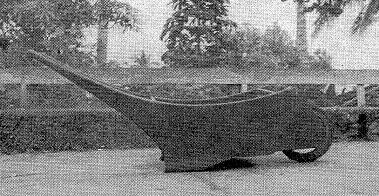

The School at Pitcairn Island.

The School at Pitcairn Island.The average attendance at the school in the early nineteen-fifties was 20 pupils, but it has steadily increased—to 28 in 1959 and 36 in 1962. Since the beginnin2 of 1959 a former pupil has helped the Education Officer with the infant classes, and in 1961 a year's training course in infant-method in New Zealand was arranged for another young girl who has now returned to teach the younger children. The school provides primary education based on the New Zealand Syllabus and practical training is given in home studies, farming, commercial practice and typewriting. Correspondence courses in post.primary education were introduced in 1957, and in 1960 a student spent several months in Fiji on a special agricultural extension course. The simple pattern of education on Pitcairn is not expected to change rauch. The island is likely to remain a Land of smallholders and handicraft traders; the Population will probably remain static, with emigration of the young offset by a return of older people; and the cultural demand, at least for some time to come, seems destined to stay on the level of an isolated coastal village in a large country. Within these limitations and the simplicity of the basic pattern of life, continuity in some esential services must be provided for and it is towards this end that policy is directed. In particular, the island has a continuing need for women with nursing, midwifery and infant-welfare experience; for men with practical training in mechanical, building, radio and agricultural technology; for local-government officials; and for adequate teaching stafl. If the education system can produce men and women for such posts it will assist social improvement, but it will create problems of its own for, besides the probable departure of students seeking Page 37

|

|

success overseas, even a small sub-professional and technical dass will have to be so assimilated into the cornmunity that the social Organisation remains balanced and stable. HEALTHThe general standard of health has been no problem on Pitcairn since, in the early days of settlement, the patriarchal John Adams stamped traditions of justice, moral rectitude and social solidarity on his flock. For a period of thirty-five years after 1790, when the mutineers landed at Pitcairn, the island was for all practical purposes completely isolated and, after the Tahitian interlude of 1831, it was succeeded by a shorter term of incomplete isolation which ended with the mitzration to Norfolk Island in 1856. Following the re-occupation of Pitcairn in 1864 there was again a period of partial isolation, terminated by the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, since when Pitcairn has been regularly visited by ships on the New Zealand run. The difficulty of landing on the island and the exposed anchorage, which is suitable only for small vessels, reinforced its isolation, since it is evident from the records that brief calls only were the rule. The islanders had, therefore, a natural protection against some of the vice and disease that played havoc elsewhere in the Pacific, although even casual contact was sufficient to introduce them to common infectious ailments such as colds and Influenza. Proof of the value of this isolation is afforded by the experience of the islanders during their short stay in Tahiti in 1831, when 17 out of a total number of 87 succumbed to disease. Throughout the 170 years of occupation there has been no resident doctor on Pitcairn Island nor, so far as can be traced, was there a nurse until an appointment  The healthy young --

The healthy young -- |

|

was made in 1934 in co-operation with the Australasian Union Conference of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, Since 1934 this co-operation has continued and it is now the usual practice for the wife of the resident Pastor to he a trained nurse. When students with sufficient basic education become available it is pro- posed to consider again the training of nurses, which was unsuccessfully attempted in the nineteen-forties. With the willingly-given assistance of surgeons from passing ships, which call at the island on an average of one approximately every ten days, or which can be summoned by radio in cases of emergency, Pitcairn is better situated for medical assistance than many small, rural communities. Occasionally, a visiting medica 1 officer is able to spend a short time on the Island, and reports by H.M.S. Warrior and the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition in 1957 commented favourably on the general state of health but noted a need for dental care. In 1962 the surgeon of the Dutch ship Willern Ruys made an X-ray survey of the population and, by arrangement with the Post-raduate Medical Committee of the University of Auckland, the Administration sent a doctor to the island for a month's visit. Between 1956 and 1960 an average of 180 non-epidemic medical cases were tre2tted in the well-equipped, Government dispensary, of which 44 per cent were for minor ailments such as the common cold, bruises and cuts and 25 per cent for eye, ear and skin infections and injuries. A few surgical cases were evacuated to New Zealand, expenses being met by 9,-overnment loan or grant when necessary. In the same period there was an average of 60 teeth extractions annually, and from 1957 to 1960 over 600 teeth were filled, principally in 1958 and 1959. There was an influenza epidemic in 1959 which resulted in one death. In 1959-60 the whole population was immunized against poliomyelitis. There were 30 births and 15 deaths on the Island during the period 1954-62.  -- and the contented old. Mrs. Ettie Christian testing her eyesight and steady hand.

-- and the contented old. Mrs. Ettie Christian testing her eyesight and steady hand.Page 39

|

|