|

|

Letters from a mariner, No. 2:

|

NO. II.

Sir — I was once (1817) bound from the islands last mentioned to Coquimbo, when we hove to under the southeast side of Pitcairn's Island, the retreat of the mutineers of the Bounty. We discovered a village under a noble grove of banyan and palm; and the inhabitants were seen hastening down the declivity by a circuitous path to the beach. I was one of five who went in a boat near to the shore, where the islanders stood on a projecting rock, making courteous signs for us to approach. But the surf was too high, and several of their young men swam off. They gave us from the water the English salutation, 'How do you do?' and one of them said in a very pleasing manner ‘I will come into your boat, Sir, if you will permít,' but not one of the whole attempted to get in till he had obtained permission. Ten came in, and as soon as seated, asked with the utmost eagerness our nation, and reason for coming to their island. The cause of our coming we stated to be, partly to obtain provisions, but principally to see with our own eyes the innocence and happiness of their little society. All were desirous to go on board, but as the sea was high, and the weather in their own phrase 'looked naughty,' I limited their number to three. They decided by lot who should go, and the unsuccessful swam off under the promise of being permitted in their turn to visit the ship. It was dark when we dropped anchor, and we discovered immediately after, a single man in a canoe that could hold but one, and which, though little better than a cockle shell, he managed dexterously. He came under our lee quarter, and called in a bold manner for a rope, by which we hauled him and his canoe on deck together. He was not encumbered with dress, wearing nothing but a free mason's apron without the emblems. |

In the morning a gale drove us off many leagues. Yet although the sea was high, our visitors showed no symptoms of alarm; but all were uneasy for the pain their situation, or ignorance of it, would give their friends on shore. Their agreeable manners and amiable dispositions made them favorites with us all: and if ever there was a golden age it must have produced people like these. I have never seen in others such natural ease of deportment or unhesitating boldness in speaking their sentiments. 'Mr Adams' seemed to be held by all in great veneration. Since their infancy, the good man has been anxiously engaged in turning their minds to good, or, in their own words, he has learnt them to love all good things and to hate every thing that is naughty.' This last is a phrase in high favor with this Solon of the sea, and if the manner in which it is used shows a lack of elegance, it indicates a simplicity that belongs to innocence. The women, notwithstanding the assurance of Adams, had bewailed the young men as lost when the vessel disappeared, and when they arrived on shore, all parties seemed frantic with joy. Our boats lay beyond the surf, and the patriarch brought off for the crews, a roasted pig. He requested our attention,' and said grace in a solemn manner and these words, "For what we are to receive, the Lord make us thankful.' In the crowd standing on the cliff, I pointed to a couple of females who the old man said were his daughters, and on my expressing a desire to see them he waved his hand in a manner that shewed he had a system of signals; for the youngest ran down the the slope and without waiting for the returning wave, plunged into the surf. She needed little aid to get on board, and in the same moment when she put her hand upon the gunwale she was seated at her father's side. |

Her countenance was decidedly English, and constantly animated with smiles. Ilaving received many presents, Hannah returned on shore, and Mr Adams consented to pass the night on board. But he could not compose himself to sleep; at every movement on deck, and we tacked frequently, he ran up and seized a rope where his aid was little wanted, and cheered the sailors with the exclamations usual in hauling. Then he would return to his cabin, where he was often heard in prayer. As ours was the first ship he had entered since the Bounty (for I think he did not visit Capt. Folger’s), perhaps the revival of old recollections was too strong for his philosophy, or perhaps he feared that we might detain him as a prisoner. My own private belief was that his intellect was a little disordered. I went on shore to see the village, and was received on the beach with a general 'welcome.' We passed through a grove of cocoa palins planted with regularity, and the broad leaves were so interlocked as to exclude the light of the sun, and produce a twilight at noon day. Had there been no birds to sing, it would have been almost dismal. The trunks were large, strait, and tall, and the whole grove looked like a magnificent temple of pillars. Near this is the village, divided by a swift rivulet of the clearest waters. The houses are of plank hewn from the tree, and the windows are sliding pannels. In the village are some noble banyan trees, which make a canopy that will almost exclude the rain. Some of them look like a pavilion, and in all it seems to a stranger that nature has borrowed the aid of art. The branches, like those of the live oak in America, extend themselves parallel to the earth; and when they require, from their distance to the trunk, a new support, a shoot like a prop falls to the ground, where it takes root like a new tree. The banyan therefore covers a great surface. |

The Otaheitan women followed me wherever I went, with inquiries of their long lost country; for they persisted in believing that I had come last from Otaheite. To Adams we gave a good boat, many tools, and some useful books. To the young people we promised a supply of spelling books,' for which they made early and anxious inquiries. Their desire to learn seemed very great. We received the spy-glass of the Bounty, and a few blank books that had been on board. We also saw the guns, which are visible at low water, though half devourred by rust. I had the pleasure to receive many pressing invitations to live upon the island. I was a waif on the world's wide sea, and perhaps it had been better for me had I been here cast ashore: for even Hannah promised that if I would remain and teach her to read, I should have a house of my own, and never be called to labor in the yam fields.' Other destinies led me away, but not without more regret than I can express, as I took leave of these innocent, kind, and happy islanders. This was more than twelve years ago, and I have never had a conveyance for the spelling books. I confess with sorrow that I have not sought one: if you can inform me of such, I will recover a little self esteem by sending those and better books, though they cannot restore' to the Islanders their lost simplicity. |

|

Notes.

— #1 —

This essay was first published as as part of Holbrook's second "Letters from a Mariner" which was published in the New-England Galaxy and United States Literary Advertiser, Joseph T. Buckingham editor.

— #2 —

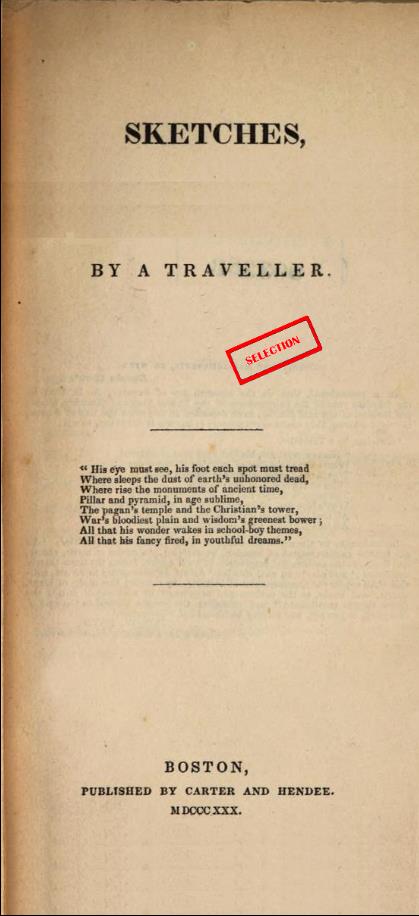

"Mr. Holbrook was the writer of a series of letters entitled 'Letters from a Boston Merchant,' — another series, entitled 'Recollections of Japan,' — another, 'Recollections of China,' — and a fourth, 'Recollections of Turkey,' — all of which were published in the Courier. The facts, which formed the basis of these 'recollections' were, of course, obtained from books, he having never visited the countries described, except some of those noticed in the 'Letters from a Boston Merchant.' A year or two before his death, he made a selection from these articles, which he published in a duodecimo volume, under the title of 'Sketches by a Traveler.'" This is from a footnote to a memoir of Silas Pinckney Holbrook by Joseph T. Buckingham, his editor at The Boston Courier and the New England Galaxy.

— #3 —

HOLBROOK, Silas Pinckney, author, was born in Beaufort, S.C June 1, 1796; son of Silas and Mary (Edwards) Holbrook, and brother of Dr. John Edwards Holbrook, the naturalist. He was graduated from Brown in 1815, studied law in Boston, and practised in Medford, Mass., 1818-35. He travelled extensively in Europe and contributed to the New England Galaxy and the Boston Courier, under the pen name of "Jonathan Forbrick": " Letters from a Mariner," "Travels of a Tin Peddler," "Letters from a Boston Merchant," and "Recollections of Japan and China." He also conducted the Boston Tribune and Spectacles. He collected his contributions and issued them as: Sketches by a Traveller (1830). He was married to Esther Gourdin. He died at Pineville, S.C, May 26, 1835.

|

|

Source.

Silas Pinckney Holbrook, 1796-1835.

This transcription was made from the volume at the Hathi Trust.

Last updated by Tom Tyler, Denver, CO, USA, December 29, 2024.

|

|