|

|

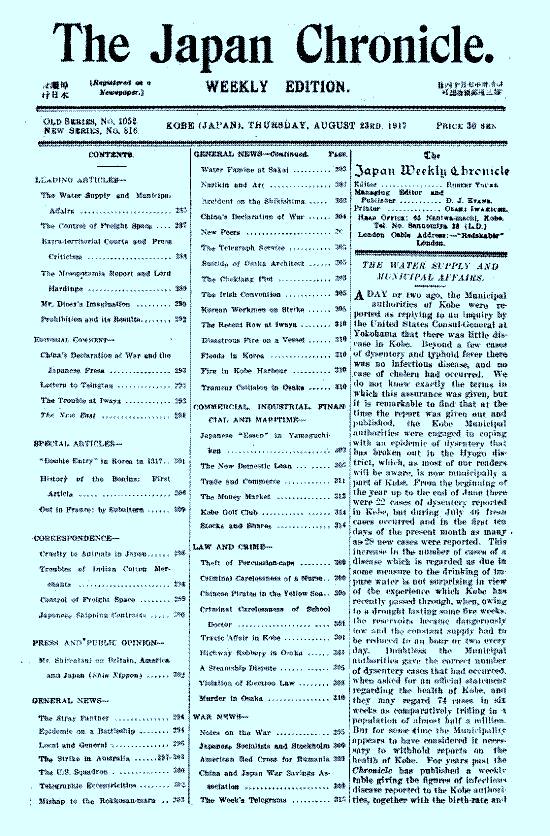

HISTORY OF THE BONINS.

EARLY JAPANESE STATEMENTS DISPROVED. FIRST ARTICLE. Last year, following the publication of the Rev. L. B. Cholmondeley's History of the Bonin Islands, there was published in Tokyo a History of the same group by Mr. Yamada Kiichi, a Tokyo journallst, the publishers being the Hoten Gijuku, of Azabu. Tokyo. Mr, Yamada goes very thoroughly into the early history Of the Bonins, and he shows conclusively that certain Japanese statements regarding their discovery are without foundation. The historical part of his book is of so much interest that we propose to quote from it at some length. The Ogasawara or Bonin Islands are an isolated group that lie out in the Pacifie Ocean far away from the Japan mainland, and for a long time the Japanese had no communication with them. It is impossible to say when and by whorna they were actually discovered, but the tradition still lives on which ascribes their discovery to a Daimyo named Ogasawara Sadayori in 1593. The story runs, that by inheritance and acquisition he had become the owner of large fiefs in the provinces of Etchu and Settsu with a revenue amounting to 160.700 koku. Deprived by aome arbitrary act Of Hideyoshi of ail but 700 koku, he appealed for redress to Tokugawa Iyeyasu, by whose intervention his revenues were increased to 50,000 koku. Latterly he took part in Hideyoshi's expedition to Korea and, having rendered meritorious services. Iyeyasu once more interceded for him in the hope of gaining him the full restitution of his former fiefs. Instead of granting this, however, Hideyoshi made him a promise to create him lord of any islands that he might discover. Strangely content, Sadayori forthwith sailed southward. and pursuing bis course onward from Hachijo, eventuallY discovered three uninhabited islands beyond, from which he returned bringing sundry samples of their products. Having thus satisfied Hideyoshi of his discovery, Hideyoshi on his part gave him a document assigning the islands as a possession to him and his posterity and designating them by his name. The tradition goes on circumstantially to relate how this same Sadayori paid several visits to the islands, but how that after him, his son Nagamichi, on a second voyage, had been compeiled by a storm to turn back and had never repeated the venture. The prohibition under the Tokugawa régime to travel abroad also put an effectual stop for the time being to further expeditions to tne islands. Fabrication by an Impostor.

Though after the opening of Japan, or we may say from the beginning of the Meiji period, a revived credence has certainly been given to this tradition of the discovery of the Islands by Sadayori Ogasawara, and amongst others by the present Marquis Okuma, the writer of the History now under notice proceeds to show how there can be little doubt that the whole story was the fabrication of an inpostcr. ln the twelfth year of Kyoho (1727), so he relates, there was e man of the name of Miyauchi Sadato who represented himself as being a descendant of Ogasawara Sadayori. He prepared an account of the discovery of the Ogasawara Islands and, with this, applied to the Bakufu (the Tokugawa Government, for permission to go to the Islands and take over his forefathers' possessions. Having had his application granted, he put to sea with his familY, but owing to stormy weather — stormy weather and high seas have played a very important part in shaping the islands' destinies — failed to reach his destination. The Bakufu had now, rather late in the day, ordered the recognised head of the Ogasawara family to investigate the legitimacy of Sadato's claim, and investigation had elicited the fact that Sadayori, the alleged discoverer of the Islands, had no place in the pedigree of the genuine Ogaaawara family. claiming descent from the feudei Lord of Fukashi in the province of Shinano. The consequence was that Sadato was not only not allowed to put out on a second vovage, but place was round for him elsewhere in exile as a punishment for his imposture. Among the arguments cited to prove that the account rendered by Sadato Miyauchi to the Bakufu was a fabrication are: — That there is no mention in the Bakufu records of any Ogasawara going wo the islands between the dates of 1593 and 1643; that in any refercnces made to the islands they are designated only as "Muninto," and that it is inconceivable that whilst Hideyoshi required ail his naval forces for Korea, a vessel or vessels should have been allowed to be set apart for a fortuitous quest of unknown Islands. This demoliahing of the Ogasawara tradition stems to be sufficiently effectual, but the point remains to be cleared up how, if this story of the discovery of the Islands in 1593 was the fabrication of an impostor in the vear 1727, the islands should subsequently have been allowed to bear the name that the impostor had tried to foist upon them. We shall have occasion to deal with this point later. Probable Real Date of Discovery.

Putting Sadayori Ogasawara's claim aside, as at least not proven, under the guidance of our latest Bonin historian we atrike the first known facts about the Japanese discovery of the islands in the year 1670. The story that follows is, no doubt, the incident alluded to by Kaempfer, who wrongly, however, though with something to be said in his excuse, gives the date as 1675. A merchant vessel carrying a shipment of oranges to Yedo from a certain Chozaemon of Fujishiro, Kishu, was overtaken by a storm off the coast of Ise on December 6th. The crew numbered seven. They were driven out to sea and had terrible experlences. Their store of rice was exhausted; they were some days without fresh water; and supporting themselves mainly on oranges, at last, about the 20th of January, drifted ashore on some unknown islands which were none other than the Bonins. Two records have been preserved or this remarkable sea adventure, one purporting to be an account prepared and sent to the Bakufu by the merchant who had been the loser of his shipment of oranges; the other, a personal account or their experiences written by two of the vessel's crew, one of them no doubt the successor to the Captain, who had diad of exhaustion the very morning after they had reaohed the island shores. After relating this incident, this latter account, which is naturally the more circumstantial and interesting, continues: — The party had a rest for about ten days following. During, this interval turtles were found on the beach, which were caught and consumed as food. Having thus regained energy they set out on a trip round the Island. It had a harbour facing south, where about twenty or thirty ships could be accommodated. It did not eeem that there were any inhabitants on the island, but at the same time it had no particularly desolate look. Other smaller Islands lay around it. The birds found on the Islands were the uguisu, iwatsugumi, yamabato, a yellowish brown bird, a red-capped bird, besides the ordinary sea birds. The fish found were black seabream, yellowtail, grey mullet, the octopus, lobsters running to about 3ft. in length, besides abundance of turtles. In February and March whales made their appearance. The party dried a catch of turtles and fish for food store for their return journey. Unfortunately, one day, while riding at anchor, the moorings of the vessel snapped and it ran aground and was broken up. This necessitated the party's having to stay on the island for about fifty days whilst they constructed a boat. A large drlfting plank of camphor wood, which they had previously secured, was for this purpoae of great service to them. The boat at last finished, they put to sea and made their way to an island to the north-west, about thirteen ri distant. A further twenty-three ri and they reached the Island of Hachijo. Here they were hospitably received and furnished with food supplies. Then trusting themselves still, it would seem, to their roughly improvised boat, they left Hachijo on the 5th of May and in two days reached the coast of Izu. Expedition to Colonise the Islands.

The story of these adventures caused so great a sensation throughout the country and excited so much curiosity about these Islands that in the third year of Yenpo – 1675 – (here we have Kaempfer's date) the Bakufu dispatched a vessel with a party of thirty-two men to explore them. The vessel put to sea on April 5th and arrived at her destination on the 29th. How so long a time was apent on the voyage we are not told. On the islands the party spent over a month, making all the required investigations and collecting specimens of plants and products to bring back with them to Japan. We are told too that, having been sent with a view of preparing the way for the establishment of a colony, they religiously set up three shrines, one to Mishima Danishin, another to Hachiman Daibosatsu, and the third to Kasuga Taishin; further, they set free five quails which they had brought with them on board. The partY started on their return voyage on June 5th and reached Shimoda on the 17th, but, for what reason it is not stated, the colonising project had already been given up, so that no practical results came of their mission. The next time, and it is after a long interval, that the islands, still possessing no other name than Muninto, come into notice is in connection with Miya-auchi Sadato's bold attempt to make himaelf the possessor of them by the assertion of his false clam to be the descendant of Ogasawara Sadayori, who himself seems to have been a fictitious personage. This episode has already been fully dealt with. Irresolute though they might be in their plans for dealing with them, the Bakufu were certainly not allowed to forget about the islands, for the writer arrays quite a number of instantes of Japanese vessels — sometimes of considerable size — being storm-driven to theit shores, and of seatnen being found stranded on them who were once more conveyed back to Japan. But perhaps these recurring reminders of the stormy nature of the seas intervening between Japan and the Bonins wisely deterred the Bakufu from too hastily giving effort to any schemes for their colonisation. |

A Dutch Reference to the Islands.

We pass on to a curious story told us of how a certain Hayashi Shihei or Sendai got into trouble with the Bakufu through the publishing of two books entitled Kaikoku Heidan and Sankoku Tsuran. In these works he predicted the foreign invasion of the country, and inserted maps to show the importance of putting certain places into a state of defence. There is nothing In this that directly concerns the Bonins, but in the Sankoku Tsuran the author relates that between the years 1776 and 1780 he had become acquainted at Nagasaki with a Dutehman named Ahrentwel Bayt, the author of a book on geography in which he states that at a point 200 ri south of Japan is an island called "Westeland" (Wild Island) which, though uninhabited end in spite of its repelling name, is abundantly fertile. This island he encourages the Japanese to take possession of and cultivate, adding that it would not be profitable for his own country (Holland) to do so owing to the small size of the Island and of its great distance away. Hayashi's book with this quotation in it from Bayt brought him into trouble. In immediate sequenee our writer informs us how, in the era or Tempo (1830-1843) there were certain "scholars of Dutch affairs," including Watanabe Kazan and Takano Choei, who incurred punishment for projecting an attempt to explore the Muninto. The two incidents put together seem intended to show that the Bakufu in any case were jealously determined to check any Dutch interest moving in a B0nin direction. THE OCCUPATION BY FOREIGNERS.

Possession Taken in Name of King George. Anybcdy reading Mr. Yamada's book wili see that he has been at pains to put together all the facts he can that go to prove that the Japanese had knowledge of, and interested themselves in these early days in the Bonin Islands. But though they had been known to the Japanese from the year 1670, the fact remains that up to the year 1827 these "Muninto" had continued to he "Muninto," and that no scheme of colonising them had been carried into effect. Thus, whan Captain Beechey of H.M.S. Blossom discovered them in the year 1827, there was nothing to convey to him that he was a trespasser on other people's property, and having spent ten days in making a careful survey ot them, he vary warrantably, as he thought, took possession of the Islands in the name of King George. Colonisation by Foreigners. It so happened that they were not much longer after this to remain uninhabited, for in the year 1830 there came to the island the first party of colonists — not however, from Japan, but from far-off Hawaii, — and they came with a British flag; and with no questioning but that they had come to a British possession. Japan on her part was blissfully unconscious of their coming, and for long remained blissfully unconscious that the islands she had neglected to occupy had now fallen to the lot of others. Mr. Yamada, of course, can only directly or indirectly derive his information about Captain Beechey's diseovery of the Islands, and the subsequent colonising of them, from sources to which we have the freer access. It is when he supplies original information from Japanese sources that his contributions to the History of the Bonins are valuable. Nevertheless it is interesting just to note how he introduces these foreign colonisers to his Japanese readers. He writes: "Though Japanese and foreign veesele chanced occasionelly to visit them, there were no inhabitanta at ail on these Islands for a long time. In 1830, however, the first year of Tempo – or 156 years after the Bakufu's exploration of the islands – a party of immigrants consisting of an Italian, Matte Mazarro, as leader, an American named Nathaniel Savory, an Englishman named Richard Millinchamp, an American named Aldin Chapin, and a Spaniard named Richard Jolinson, accompanied by seventeen labourers, arrived at Chichijima from Hawaii to engage in agricultural pursuits. This was the first attempt at exploiting the naturel resources of the isiands. After this there were yearly arrivais of foreign immigrants." Now for "Richard" we should read "John" Millinchamp; and "Charles," not "Richard," Johnson was not a Spaniard, but a Dane: but the most noticeable point in the above relation is that nothing is said of the British character ot the expedition and, with Commodore Perry, the writer will not allow Matthew Mazarro, – the man with the Italian name and the original leader of the party, – to have been a British subject, which from varions evidences he clearly must have been. Mr. Yamada continues: – "As for Japanese, in the ninth year of Tempo – 1838 – Hagura Seki, a local administrator under the Bakufu, when he made the round of the seven Islands of Izu, attempted to explore these Islands (Bonins), but his atternpts were frustrated, and no more official voyages were made to them up to the second year of Bunkyu (1862)." This vague and frustrated attempt, then, of Hagura Seki is all that Mr. Yamada can point to of Japanese official interest in the islands for the first thirty-two ycars during which the foreign eettlers were in undisturbed possession. Commodore Perry's Visit.

There now follows the account of Commodore Perry's historical visit to the islands in the sixth year of Kayei (1853), but Mr. Yamada only tells us in brief what we can gain full knowledge of elsehere. He notices, however, that the purchase by the Commodore of land for a coaling depôt called forth from the British Government demand for an explanation of his action. This was the only occasion, as Mr. Cholmondeley points out in his book, of the British Government's professing any concern in the Benin Islands. Mr. Yamada naturally mentions the incident, because it evoked from Commodore Perry the reply, that he did not regard England as having established any claim to the ownership of the Islands, which, if thy;sic] belonged to anybedy, should belong by right of priority of discovery to Japan. Japanese Action.

At last, the writer continues, the Bakufu had been awakened from its long slumbers. Learning that Commodore Perry had visited the Islands and that Europeans and Americans had emigrated thither, the Gavernment resolutely made up its mind to colonise the islands, though the authorities felt no small amount of apprehension and anxiety over the execution of the project, and much time was spent in preparation. Eventually it was decided to send to the islands a High Commissioner in the person of Mizuno Chikugo no Kami, with a warship under his command carrying a force of ninety men. The following extracts, as bearing testimony to his commendable foresight, are quoted from a scheme submitted by him to the Bakufu: — "I hear that many foreigners are now settled on Ogasawarajima. It is possible that among them there may be many, treacherous and unruly persons who may treat our arrivai with disrespect. Evert one such might draw the ignorant people round him and so bring about a serious situation. The making of many arrests might have an undesirahie effect in alienating the good will of the people generally. My conclusion then is that it would be the wisest course to overawe all opposition by a display of military force. I would therefore recommend that the warship be fully equipped with big guns and other weapons, and 1 would ask that arrangements be made to enable us to fire a succession of salutes on arrivai in harbour." "It would be advisable that the Expedition should first touch at the Island or Hachijo, and that the younger inhabitants should he urged to emigrate to the Ogasawara islands, because their simple mode of life better fits them for emigration, and they are not so dépendent on rice diet as the Japanese on the mainland. Further with the view of assisting such emigrants, that a good supply of food, implements and other necessaries be taken on board." Arrival of a Japanese Warship at the Islands.

All the necessary preparations concluded, the warship Irin-maru left Sulnagawa on December 4th in the first year of Bunkyu (1861) and safely arrive at Chichijima on the 19th of that month. As soon as the party landed (we hear nothing about a succession of salutes) they hoisted a Japanese flag at the top of Asahiyaina, the highest peak overlooking the harhour, and gatherIng the inhabitants of the island together, made formal announcement to them that the islands, on which they had been residing, were Japanese territory, not that they should be left in undisturbed possession of the land and other property which they were at the time holding. By this announcement and a subsequent liberal distribution among them of wine, candies, utensils, etc., we are told that the goodwill of ail the inhabitants was successfully secured. A number of regulations issued by Mizuno Chikugo no Kami and Hattori Kiichi are given. The High Commissioner ami his party made a stay of three montha during which they paid a visit to the South Island, Hahajima, and to some of the smaller islands of the group. They established government offices on the main island at Oguira, on the south side of the harbour, that is, on the opposite side to where the little town with its official buildings is to-day: and, to-day, at Oguira may he seen the great slab monument they erected with a long inscription recounting how the islands had been discovered by the Japanese, and as a memorial to those Japanese who hed perished on the islands by shipwreck. "Having thus," so we read, "taken colonisation measures of immediate importance, Mizuno and Hattori decided to return te Japan, and setting sail on March 9th, 1862, the second year of Bunkyu, arrived at Shimoda on the 15th that month." Japanese Estimate of Foreign Settlers.

In their Report, submitted to the Bakufu, it was stated that on Chichijima, that is, on the chief Island, there were thirty-six foreign settlers occupying nineteen houses: that for the most part these were formerly seamen on board warships |

or whalers, who had abandoned their service owing to advanced age or sickness, and had settled down on the islands; that they were ail people of an inferior class, and that there was no one of high position among them deputed by any Government to fulfil any mission." Attitude of British Minister.

We shall be seeing how this colonising scheme, at last so definitely undertaken, was to come to an untoward end after but a year's working. At this point, hawever, it will be convenient to turn to Mr. Yamada's account of the negotiations previously entered into with the Treaty Powers respectively of Great Britain and the U.S.A. "When the Bakufu," he writes, "set about colonising Ogasawara-jima they notified the scheme to the Treaty Powers. Mr. Harris, the American Minister, made no demur to the proposai, stipulating only that the vested interests of what American settlers there might be on the islands should be respected. The British minister, on the other hand (who at that time was Sir Rutherford Alcock, though his name is not given by Mr. Yamada) asked to be allowed time for consideration. When he at length sent in his reply, he called the attention of the Bakufu to the fact that though the early discovery of the islands by the Japanese was indisputable, there had been no undertakings carried out by the Japanese on the islands, but that they bad been lett unoccupied and uncared for. On the other hand he pointed out that, as a result of a visit paid to the islands by a British ship, there were to-day a number of British and other settlers on the islands. In conclusion he invited attention to a proposai that had emanated from the United States to the effect that the islands should be regarded as a possession common to the Powers and a place of refuge for vessels in distress. In a later official note, the British Minister represented that according to Western law Japan's ownership of the Islands had been already forfeited, and that there were various consideratlons that made it advisable now that the Islands should not be regarded as the possession of any one Power. None the less the British Minister was prepared to give assurance that no objection would he made on the part Of his Government to the Islands coming under the dominion of the Mikado, and to the free emigration of his subjects thereto, provided that foreigners were guaranteed unrestricted access to their ports and full protection of their interests. Reply of Japanese Government. To this Note of the British Minister the Bakufu made rejoinder that the foreign settlers on Ogasawara-jima were no ordered community under any Government, but were just a heterogeneous lot of men whom chance or inclination had brought there; whereas the Japanese intended establishing a well-ordered colony on the islands with responsib!e officiais to direct its affairs. Also, they had it under contemplazion to establish a coal depôt, and to see that the islands were adequately supplied with live stock and vegetables for the benefit of foreign vessels calling there. With this rejoinder the matter dropped. Failure Of Bakufu Colonisino Scheme.

Alter Mizuno's return, the order of events is rather vaguely chronicied. We are told that Kobana Sakunoshin was appointed Governor; that, subsequently, the Choyo-maru was dispatched to the islands with forty koku of rice and ten of wheat: that the authorities decided to move forty households from Hachijo to the islands, and that this décision was communicated to Egawa Tarozaemon, the administrator of Hachijo; finally, that a proclamation was made throughout the country that Ogasawara-jima having been opened, emigration thereto and whale fishing would be permitted on application to the authorities. But vigorously though the colonising scheme is thus represented as being prosecuted, its end was fast approaching. These were days when Japan was passing through a crisis. "There were Internai and external complications," 'Mr. Yamada writes, "and the downfall of the Bakufu seemed imminent. It was impossible for the authorities to continue to give attention to colonising work which was of no pressing importance, and so it came to pass that the undertaking was suspendsd and the colonisers, officiais and all, returned to Japan. This was in May in the third year of Bunkyu (1863)." . . . .

|

|

Source.

"History of the Bonins: Early Japanese Statements Disproved (First Article)".

This transcription was made from the volume at Google Books.

Last updated by Tom Tyler, Denver, CO, USA, Nov 8 2022

|

|