|

|

|

PART I.

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE SPERM WHALE |

|

. . . .

On another occasion, and while upon the Bonin Islands, searching for shells on the rocks, which had just been left by the receding sea-tide, I was much astonished at seeing at my feet a most extraordinary looking animal, crawling towards the surf, which had only just left it. I had never seen one like it under such circumstances before; it therefore appeared the more remarkable. It was creeping on its eight legs, which, from their soft and flexible nature, bent considerably under the weight of its body, so that it was lifted by the efforts of its tentacula only, a small distance from the rocks. It appeared much alarmed at seeing me, and made every effort to escape, while I was not much in the humour to endeavour to capture so ugly a customer, whose appearance excited a feeling of disgust, not unmixed with fear. I however endeavoured to prevent its career, by pressing on one of its legs with my foot, but although I made use of considerable force for that purpose, its strength was so great that it several times quickly liberated its member, in spite of all the efforts I could employ in this way on wet slippery rocks. I now laid hold of one of the |

tentacles with my hand, and held it firmly, so that the limb appeared as if it would be torn asunder by our united strength. I soon gave it a powerful jerk, wishing to disengage it from the rocks to which it clung so forcibly by its suckers, which it effectually resisted; but the moment after, the apparently enraged animal lifted its head with its large eyes projecting from the middle of its body, and letting go its hold of the rocks, suddenly sprang upon my arm, which I had previously bared to my shoulder, for the purpose of thrusting it into holes in the rocks to discover shells, and clung with its suckers to it with great power, endeavouring to get its beak, which I could now see, between the roots of its arms, in a position to bite! A sensation of horror pervaded my whole frame when I found this monstrous animal had affixed itself to firmly upon my arm. Its cold slimy grasp was extremely sickening, and I immediately called aloud to the captain, who was also searching for shells at some distance, to come and release me from my disguting assailant – he quickly arrived, and taking me down to the boat, during which time I was employed in keeping the beak away from my hand, quickly released me by destroying the tormentor with the boat knife, when I disengaged it by portions at a time. This animal must have measured across its expanded arms, about four feet, while its body was not larger than a large clenched hand. It was that species of sepia, which is called by whalers "rock-squid." Thus are these remarkable creatures, from the different adaption of their tentacles, |

and slight modifications of their bodies, capable of sailing, flying, swimming, and creeping on the shore, while their senses, if we may judge from the elaborate mechanism of their organs, must possess corresponding acuteness and perfection. But for the description of the anatomy of these animals, I must refer the reader to Mr. Owen's masterly paper on that subject, in Todd's Cyclopaedia of Anatomy, above quoted. . . . .

|

|

|

PART II.

SKETCH OF A SOUTH-SEA WHALING VOYAGE |

From the beginning of June to about the middle of September we fell in with great numbers of large whales, which we saw sometimes every day for weeks, so that we were kept in constant excitement with chasing and capturing them; for the details of which operations I beg to refer the reader to the account contained in the "Chase and Capture of the Sperm Whale," in the first part of this work, chapters xii. and xiii. About the middle of September we found the weather becoming tempestuous; the whales also became very scarce, or seldom seen; they appeared going off to the southward, no doubt in search of more abundant food; for now the sea, which during the two former months had teemed with polypi, medusae, flying-fish, and squid, was getting quite deserted. They had, towards the latter end of September, nearly all disappeared; and no doubt the squid, upon which the sperm whale feeds, had taken its departure also, for during the two previous months we frequently had seen detached portions of them floating on the surface, upon which the whales had been feeding, and which no doubt had escaped from their jaws; but now nothing of the kind could be seen, and we therefore prepared for our departure also, and, steering about south-west, on the 5th of October 1831, made the Bonins, which form a small group of islands not far from the coast of Japan, in the longitude of 141° 30' east, and in the latitude of 26° 30' north. They were, at the time of our visit, all uninhabited except North Island, upon which two or three Europeans and a few Sandwich Islanders were endeavouring to form a settle- |

ment. We saw numbers of whales surrounding those islands, and we had the good fortune to capture several; they were mostly females accompanied by their young ones, although we saw some large males occasionally, and once in considerable numbers; I then imagined from seeing so many together, and all of them going fast in one direction towards the south-west, that they were migrating. But we had not been long off those islands before we experienced one of the most dreadful typhoons, or Indian hurricanes, that the world ever produced, and which astonished some of our oldest seamen. We had had nothing but calms and light airs of wind for several days, when our attention was drawn to an increasing swell of the sea which came from the north-east, soon after which the atmosphere assumed a very sombre and melancholy appearance, having a peculiar light, from the sun's rays piercing remarkable clouds of a dull ochreous red colour, which tinged the ship, the sea, and everything round. All of us expected some convulsion of nature was about to ensue, which caused us to feel both sad and uncomfortable, and even the sea-caps that broke upon the enormous waves, which had now frightfully increased, seemed to us to make a melancholy moan. The birds which before had attended us in considerable numbers, now left us to our lonely fate, and had betaken themselves to some safe retreat at a distance, or had resorted to the hollow rock, the thick forest, or shady glen. Our captain, not behind in care for the safety of the ship, ordered all sail to be taken in |

except a new main-topsail and a storm-trysail, which we were obliged to have bent to keep the ship somewhat steady in the prodigious swell which still continued to increase. In the second night after the rolling of the waters had commenced, the wind suddenly sprung up, and increased during the night to a hard gale, which however died away at sun-rise, and we again found ourselves without wind, the ship being left entirely to the mercy of the waves, which caused her to roll most frightfully, her chain-plates striking the water occasionally with terrific force, and the waves striking against the stern, so that the violent shocks thus caused at times jerked us off our seats. Some of our sailors thought the gale of the preceding night had finished the convulsion; but in this they were much mistaken, for about three p.m. the wind again suddenly arose, and in about half an hour blew a complete gale, which continued to increase in violence until about two a.m. the following morning, when a sudden howling blast of wind of extreme violence laid the ship entirely on her beam ends, carrying the storm-trysail away, with all our trifling movables from the decks. The uproar which was set up at this time from the howling of the wind, the beating and dashing of the waves, the working of the ship, the creaking of the masts and clashing of the back-stays, intermixed with the hoarse calling of the sailors, made "night hideous," and rendered the scene altogether indescribable. That was a dreadful night to me, and to all on board; we met each other with melancholy looks, at the same time |

clinging to anything which was within reach, to prevent ourselves from being thrown down. The blustering bully of fine weather now looked pale with affright; shivering and shrunk, his mind had forsaken him, and not a word escaped his lips; the dashing spray, which at times flew over the decks, caused his craven soul to cower in pitiable plight: but those who might have been thought, from their gentleness and civility, men wanting nerve and courage were now seen facing the danger with unaverted heads, quiet – yet bold, unassuming – yet proud; they feared not the raging of the elements, because, knowing their own hearts, they trusted to Him who "rides in the whirlwind and governs the storm." All of us longed for morning, and when it broke, an awful sight presented itself. The typhoon was still howling in all its fury, and it was so powerful that it appeared to strike the ship like something solid, or similar to a rush of water; a lull for a few seconds would ensue, and then heavy and sudden blasts would come on in quick succession, striking the ship with such amazing force that made every plank to shake in her well-constructed frame. The ship now plunging headlong into an immense hollow amid the waves, and now rising rapidly on the top of one, while another the next moment threatened to overwhelm us, and finish the catastrophe, – all conspired to render our situation an awful one. At about eight a.m., I accompanied the captain to the top of the companion-ladder, and we both sustained ourselves in the erect position, although with great |

difficulty, by firmly holding the capstan with both hands while we were anxiously watching the ship wrestling with the enormous waves; every time that she plunged her head into them the masts bending to such an extent that we every moment expected them to go by the board, –the carpenter's axe slung to windward ready to cut them away if necessary. A prodigious wave came careering and roaring along towards the weather-bow of our ship – she struggled to avoid it, but she pitched almost perpendicularly headlong into a deep hollow, which came immediately before her, – the monstrous wave lifted its gigantic head nearly as high as the foretop, and then fell completely over her decks, even to the main hatchway – it was a dreadful moment! The sudden cries of our brave mariners were heard above the storm, as they gave command or uttered their concern. The ship remained as if she was fixed in the wave for a few seconds, she was unable to rise from the water which held her under its weight, but she recovered herself with a jerk, and the massive bowsprit was broken like a reed; she rose upon the next wave, another struck her, and threw the wreck of the bowsprit across the forecastle; there was an immediate rush made forwards by the crew, who secured it with lashings; immediate attention was also paid to the foremast, which was now likely to go, but it was properly secured in time to prevent the calamity. The ship now rode more easily, not pitching so much, and we endured the hurricane till near sunset before it began to decline; but by sunrise the following morning the sea had fallen, the face of |

nature wore its accustomed brightness, the air was serene and sweet, and the hurricane had passed. A few days after we had experienced the typhoon, we ran in under the lee of South Island to repair our damage, and two boats were sent on shore to obtain some fish, plenty of which surround these islands. When we got on shore we saw the devastation the storm had committed on some parts of the island. Large tamana trees, which are a kind of mahogany, had been blown down, while the smaller trees were damaged in various ways to a frightful extent; large masses of coral had been detached from the rocks by the fury of the waves, and were driven and left high upon the beach. Winding along the indented and rocky shore in the boats, we suddenly came to the mouth of a marine cave of considerable extent, and the boats were headed in, to explore the beauties of this solitary place, situated so far from the common haunts of man. When we had ventured within a short distance of this ocean grotto, we were all greatly delighted at the natural beauties which adorned it in every part; we could not form any idea of its extent inwards, for all was darkness in that direction, although we must have been at one time fifty yards within its mouth, and where the sea still formed its floor. About twenty yards within its entrance was the spot which nature had fixed upon to bestow her beauties with the most liberal hand. If the eye ascended, then its high and vaulted roof was seen, fretted and time-worn into a thousand fantastic forms, – the long stalactites hung down midway, and pierced the |

dingy light with stems of various shape, with glistening aqueous points, – while stretched beneath us a scene presented itself which words cannot describe; the sea-water which entered this cavern was of a beautiful crystal clearness, as pellucid as the air, the rays of a powerful sun penetrated its depths, and illumined every object beneath its glassy surface. The bottom of the cave was formed of many masses of broken rock, all lying in chaotic confusion, forming points and clumps, arches and apertures of all sizes and forms, these were tufted, lined, and embroider ed with oceanic ornaments. On a mass of red coral grew a feathery tuft of marine vegetable, shooting delicately tall through the crystal space, while others of various forms enchained some rocky points, and close beside the ocean-fan expanded. Entwined around a rocky column was reared the tender sea-green stem of fucus, and at its feet a coarser kind matted the uneven floor; another ocean plant extended its broad leaves across a rocky arch, while others, composed of hair-like fibres, drooped from a shelfving rock, and fringed the fairy scene; and some knotted and woven, in various forms arrayed, finished this Neptune's bower, growing from the oosy sand or from the stony clumps. Around corallines of various colours – red, white, blue, and yellow, constrasted their various shapes and hues, and offered with tempting hand the rarest beauties from great nature's store. Roaming through these wild scenes, hundreds of fish appeared, of curious forms and brilliant hues. The teira, the aruanus, and vespertilio, shewed their beauteous shapes, while two |

of those chetodons came close to the boat, and stayed to view us for a considerable time – these remarkable fish are of an oval form and flat, of a rich silvery colour delicately striped downwards with azure bands, swimming in a perpendicular position, and with two long and slender fins, one curving upwards from the back a considerable length, and another curving downwards from the opposite side. These beautiful inhabitants of the ocean remained for some time observing our boat, sometimes gently reclining themselves as if to catch a more extended view; others, of curious forms and various colours, were darting and gliding in and out of different crannies or openings in the rocks in search of prey, or impelled by fear, – several large cray-fish moved their antennae from under projecting points or rocky shelves, while the beche-de-mer, star-fish, and sea urchin, filled the rich scene, – the dark and wandering corie moved slowly along the wet and slimy rock, and the prickly clam, with its extended valves to catch its straying food, remained fixed in the deepest cleft, while pointed limpets studded the rough walls, completing the objects in this ocean cave. As we were looking at an object close to an abyss which appeared among the disjointed rocks, of small extent in width, but from appearance of almost interminable depth, there arose suddenly from out of it, gurgling and opening his enormous jaws, with his eyes glaring around, an immense shark, – he was only a few feet from us, and although we all shuddered at the sight, we felt thankful that we were in the boat, and safe from |

his lacerating teeth. The formidable monster laid his whole length close alongside of us, and did not attempt to stir until I endeavoured to pierce him with the point of the boat-hook, which I thrust at him with all my strength, and he then only moved slowly away to a short distance from us. As we were passing away from this romantic spot, which I have vainly endeavoured to describe, several sharks assailed the blades of our oars with great fury with their teeth, and it was quite a common occurrence for them to dart at a hooked fish at the moment we were hauling it on board the boat. Oftentimes when I have been fishing off these islands, have I observed them slowly moving towards my bait, and when they have just been in the act of seizing it I have jerked it from them, and at times have been obliged to do so frequently before I could get rid of my troublesome and disgusting assailants. Of course if they succeeded in getting the bait within their merciless jaws, away went your tackle in an instant with extreme force, and such an event when it happened always filled me with sensations of the greatest disgust, and even horror. Whalers, whenever they happen to be near the shore, are much in the habit of visiting it, whether it be inhabited or not, with a view of obtaining fish or turtle; and if it should be inhabited, they then visit it to trade with the natives, either for food of various kinds, which they may possess, or for curiosities, such as shells, clubs, spears, and other things of the like nature. They are therefore frequently meeting with accidents when in their boats pursuing such avocations, either from surf or sud- |

den storms, which sometimes arise in a few minutes, allowing them no time to get on board the ship, or to a place of safety on the shore. I need not say, that in consequence many, very many, fatal accidents have occurred to boats' crews while engaged in such excursions, and as I was concerned in one of a terrible nature myself, I have thought the following description of it might prove interesting to the reader, and that its insertion may not be deemed irrelevant to the plan and object of this sketch. A BOAT ADVENTURE OFF THE BONIN ISLANDSWe had been cruising after the spermaceti whale for several months, and had been very successful, yet we found ourselves getting tired of the chase in consequence of having been without fresh provisions for several weeks, and all of us were longing for a fresh mess, and a little relief to our minds in looking upon the land, – for if we could only gaze upon its verdant surface, be near to it and inhale its exciting odours, we though ourselves exceedingly happy, – for it is a vast relief to look upon one's natural element, after having been absent from it several months, with naught but sky and water for our constant view. The captain, in consequence of our wants, now determined to run in under the lee of South Island, which is one of an uninhabited group, called the Bonins, that lie a few degrees to the eastward of the coast of Japan. |

We had a fair wind, and about three p.m. we were within two miles of the lee side of that island in smooth water. The foresail was soon hauled up, and the main-topsail lying aback, when a boat was lowered, and quickly filled with its crew and fishing apparatus, for the purpose of paying a visit to the edge of the rocks, and to procure as many fish as possible before sunset. I, as was usual on most boat excursions, accompanied them to partake of the exciting sport. We got close in with the land at about four p.m. and ran inside a group of rocks, which lie off South Island to the westward; we here in consequence lost sight of the ship; and seeing numbers of fish in this place, five or six of us soon had our lines in readiness for the sport, having despatched a New Zealander through the surf to catch some small crabs which inhabit the rocks, and form excellent bait for the fish which are found in those seas. He soon returned with a considerable quantity; and immediately the fish saw the enticing upper part of a crab's leg suspended, they darted upon it as if even death was a trifle when put in competition with the excessive pleasure they experienced in tasting the delicious morsel; for although crabs are such dainty fare to those finny cormorants, still they are sly fellows, and know how to make themselves scarce. We were soon in full operation, taking fine large fish almost as fast as we could cause the hook to descend deep enough; and we were only fishing in two fathoms and a half water, just outside the surf, so that we could perceive all our fish take the bait. |

But what a delightful scene was here! We were looking into the beautiful ocean – it was as clear as crystal; the bottom was composed of masses of broken rock, crowned with tufts of many-coloured coral, having the appearance of the ruins of empires covered with time-telling verdure; – and, what an immense multitude of fishes enlivened the scene! Some darting – some moving slowly and cautiously – some gamboling through the briny waters, and appearing to do so without an effort, – and now, to describe their various beautiful colours, what a task is there! Like the vegetable productions of those sunny climes, there appears to be no termination to the blending of the splendid colours of the rainbow in producing so many rich and exquisite tints; and as it is with the beautiful tropical flowers, so it is with the living beings which inhabit the Indian seas, that constant good-giving luminary the sun no doubt acting the same on both, as regards the brilliancy of their colours. They were of all sizes and shapes; and now and then a huge shark would make his unwelcome appearance, rising out of some abyss or ocean cave, like a wolf from his glen, prowling in search of innocent victims; or like a vulture coming from its secret nest, in the ruins of some ancient temple, to fatten upon the innocent in the sunshine of their happiness. An involuntary feeling of horror pervaded our frames; as the lines now and then touched these monsters' sides, they were drawn up with a convulsive twitch, for fear that they should engulf the bait within their merciless jaws. It is difficult to describe the whole of this feeling |

or the cause of it; but it most probably arises from the naturally uninviting, disgusting appearance of this wolf of the waters, combined with a sudden reflection upon its well known blood-thirsty, cruel, and utterly merciless character. The sun was now very near the horizon, and of course the light of the day was subsiding, when I reminded the third mate, who had the care of the boat, that it was time we should be thinking of taking our departure, and advised him to weigh our boat's anchor. He accordingly gave orders for the line to be coiled up, and the anchor weighed, for we had caught enough fish to serve the whole ship's crew for two or three meals; but the anchor had unfortunately become fouled, or fixed in between two large masses of detached rock, and it was a long time, and with a great deal of difficulty, before we succeeded in getting it clear. We did this at last, but not till it was nearly dusk; the men immediately sat to their oars, and did their best to get outside the land in time to get a sight of the ship before dark; but what was our surprise and chagrin when we could not discover her in the direction we expected. The oars were fixed apeak, and we all stood up in the boat anxiously looking for our only home. In a minute or two our New Zealander called out in an exulting tone, that he could see the ship: it could not escape his eagle eye. We all looked in the direction in which he pointed – we all became convinced it was the ship. We could make out her three masts like black streaks in the gloom, but she was in quite a different direction from that in which we |

left her – for things had entirely altered – the face of nature had changed – the wind had shifted, and blew much stronger; instead of being now on the lee side of the land, the wind was blowing along the shore. The ship had been driven to leeward in consequence of the change in the wind and the strong current that sets to the westward. Not a moment was lost in putting the boat's head in the direction of the ship, and we kept that course as well as we could by the aid of a star, which now appeared in the dark firmament. The boat was steered by the mate, as is usual on such occasions, he being considered, and with propriety, the most proper person to do so. It now became quite dark, and we had continued our course for some time, and nothing further had been seen of the ship – nothing heard except the breaking of the "seacaps" and the distant roaring of the surf, with now and then an ejaculation from the mate to the New Zealander to "look out," when in a moment three or four of us saw a light quite on our beam, but at a very great distance; it appeared even with the surface of the ocean. We soon discovered it to be a blue light, which the captain had no doubt ordered to be burnt to apprize us of the situation of the ship, but from that moment a feeling of hopelessness ran through us of reaching her. The wind was freshening every moment; it was blowing a stiff breeze – the ship was too far off for us to see a lantern suspended in her rigging, and we knew that there were only one or two more blue lights on board. The sea began to run higher and hither every moment; |

and there was every appearance, on looking around us, of the coming of a bad night. Every now and then the foam of the waves broke over us in a merciless manner, and two or three of the crew were employed in baling very frequently. Under these unfortunate circumstances I proposed to get near the land, in the event of very bad weather coming on, so that we might still possess a slight chance of saving our lives, by endeavouring to run the boat into some creek. This was opposed by the mate and several of the crew in a positive manner. They stated that there could be no hope of landing even if we could get near the shore, for they knew of no inlet in this part of the coast in which a boat could find shelter from the storm. I told them I had noticed several places in the surf, through which I thought a boat might venture, but more particularly one which I had observed while fishing, – although it was a dreadful place even to look upon, much more to venture into; but it was a forlorn hope in case the wind should increase much more, of which I had little doubt, and so they thought also, as I could observe in their melancholy looks. All this time the boat's head had been kept in the direction in which the blue light was observed, but now the men began to flag at their oars; there was a general murmuring among them, – they were cold, wet, and much fatigues, and they knew there was no hope of reaching the ship. We now saw in the horizon, but faintly, a glimmering bluish light spring up suddenly; it was in a direction from the beam of our boat, at an |

immense distance, but we could not distinguish the flaming body from which the rays of light proceeded; it appeared hidden in the ocean; – there appeared light springing out of darkness, but in it there was no help for us. We all concluded that the captain had fired another blue light, which had only the effect of increasing our hopelessness; for the crew exclaimed, "She is hull down," meaning that the height of the convexity of the sea between us and the ship was greater that the height of the body of the vessel, and consequently we could not observe the flame of the blue lght which was burnt from her deck, but only the rays of light which diverged from it. Our situation was becoming more and more alarming every moment; there was at this time a terrible sea running; astern appeared the gloomy form of the land – above a dark and frowning firmament, looking angry and inclined to mischief, – below, the vast ocean, getting up also into a terrible mood; like unto a giant snake were its undulations; its sea-caps performed its hissing, and its wide jaws were formed of two huge seas ready to engulf us. We were now obliged to keep the boat's head to windward, so that she might be "head to sea," to prevent our being swamped, when, looking towards the same quarter, we observed a small bright speck in the heavens, which was slowly expanding into an arch. I was sitting by the side of the mate, – I saw him observe it with dismay; in a moment there was a strong feeling |

to gain the shore manifested by the whole crew; they would rather be dashed to pieces against the rocks than founder silently on the bosom of the ocean without a chance of escape. They understood the sign which the Almighty in his goodness is pleased to hold out to his creatures, that they may escape into some protective glen or cave from the violence He is about to inflict on nature for some wise purpose; – they knew that in a very short time there would be a convulsion of nature, – that there would be an Indian hurricane, which is more violent than any other in the world, – that aged trees would be torn out by the roots, – that the sea would be like an agitated cluster of mountains, striking against each other with awful force and impetuosity, – raising clouds of mist, which would be swept away with almost the rapidity of lightning. The boat's head was put about three points off the wind, taking the sea upon her bow, and she was headed in as much as possible for the shore. Enormous exertions were not made by the men to gain the rocks, trusting to Providence for a landing-place; I was asked by the crew almost in one voice, if I could recollect the spot where I had noticed the opening in the surf. I replied I thought the boat's head was directed towards it, – I formed this idea from the appearance of the high land, the figure of which I had noticed, its black upper edge could just be observed raised in the clouds: the rowers increased their exertions, they cheered, they were answered by the roaring surf, which we heard louder and louder every moment, in a short time we could |

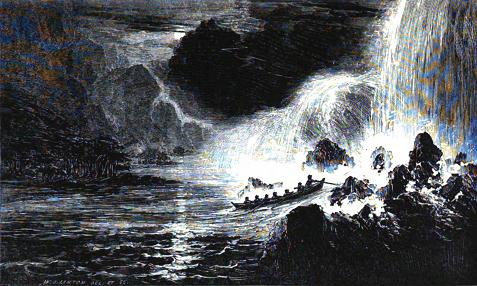

observe its wild forms dancing in the air to its own wild sounds – but there was destruction to us in it, death was in its foaming embrace! Around its base horrible sharks were prowling for the unfortunate victims of the troubled waters. We could just observe a breach of continuity in the "rollers," – it was the passage I had seen and had spoken of; we appeared to be approaching it rapidly, more so than the strength of our oars could impel us; there appeared to be a rapid current setting in through the opening – the crisis approached! The men simultaneously ceased rowing forward, and backed their oars to prevent themselves and boat from being whirled to destruction; the passage was narrow, in its centre there was no surf that we could perceive in the darkness, – but on each side there were tremendous pillars of raging foam. We all remained in doubt what to do, the darkness was still extreme, it appeared impossible to pass through without getting into contact with the sides of the channel, which looked like a marble sepulchre, opening its jaws to receive us. A few bright flashes of lightning, succeeded by terrific peals of thunder, and which were followed by a howling blast of wind, left us no choice; the boat was now drawn by the current and impelled by the furious wind and waves into the pass. In an instant we were surrounded by the foaming waters, far above our heads – they appeared about to overwhelm us – there was a death-like stillness amongst us, each grasping in an agony of mind some part of the boat. At this moment a light was held out by an invisible hand, we could perceive our situation more |

critically, the mate with one powerful stroke of the steering oar saved us! We escaped from the mighty power of the water, and were driven along with great velocity into a beautiful smooth bay, away from the foaming billows (see cut); the storm rolled over our heads; we could hear its violence behind us, but we were protected from its rage, and heeded it not, – everlasting thanks to the invisible hand of Him who held thee out, pale Cynthia! To Him who drew the dark curtain from before thy bright face in the moment of need, when the demon of darkness and death was hovering over us. We soon reached the termination of the bay, and landed upon a small sandy beach that was situated between two immense masses of broken rocks, which reared their uncouth forms high into the air. At a small distance from the edge of the water and at the back of the beach, an extensive forest of tamana trees commenced, some of them being of gigantic size, whose wide spreading branches shut out the few rays of light which shot at times from the silvery moon – forming dark arbours for the retreat of the night bird, and where the flying fox (with which this island abounds), and the night-loving bat, might revel unreached by the light of day, whose unseemly forms are hidden in the shades of evening, as if nature felt herself disgusted with the sight of beings so different in form to those inhabitants of the air which rise with the glorious sun, whose beauty of shape enchant us, whose brilliancy of colour delight us; but nature, all wise, animates with those shady beings the stillness of the evening for some great purpose who |

BONIN ISLAND – BOAT PASSING THROUGH THE BREAKERS. |

join with the unseen spirits of darkness, which are said to "walk the night" while the rest of nature lies in profound repose. A fire now became the first object of our attention: what was our sorrow when we found that we had left the ship without the necessary apparatus for obtaining one, – but our genius of good fortune had not yet forsaken us. In the person of the New Zealander we found a fortunate assistant, who by the friction of rubbing two pieces of wood together produced to our eager eyes a flame, which soon ignited a pile of wood that we had gathered for the purpose, and we began to prepare a repast from the fish we had been so fortunate as to capture. Our New Zealand friend, by a process peculiar to the tribe to which he belonged, quickly removed by the aid of his thumb nail the strong and large scales of a very fine fish, then thrusting a long stick into its mouth, he stood to windward of the blazing fire, and by turning the stick frequently round, soon cooked in a masterly manner the unfortunate inhabitants of the ocean. In two old shells he found upon the beach, in one of which he placed a portion of the fish, while the other contained a little salt water for sauce, did our useful companion serve up to myself and the mate this humble meal. This plan was quickly followed by our companions, and in a short time all but myself might have been seen in the arms of Morpheus; they were much fatigued or they could not have slept, for now the storm had increased to tenfold violence. Standing alone upon the beach, I observed with awe this convulsion of nature, |

the very ground trembling under my feet from the forcible beating of the surf – the wind groaning and howling through the forest, and against the rocks, with terrible strength; now and then might be heard the cracking of some huge tree, which could no longer withstand the ruthless fury of the blast; and now a stream of fire darting its zig-zag course with wonderful velocity buries itself in the briny and troubled bosom of the ocean, lighting up all nature with its lurid flame, shewing the agitated waters hissing and foaming in the distance, followed by horrid sounds of thunder, terrible in the extreme, causing a sickening of the very soul. I felt desolate, as if the whole world had become a chaos, except the spot on which I stood, – I and my companions, like the family of Noah, were the only saved! With what agonized feelings did I think of my beloved one, and my dear kindred; – could she but have cast a look across the world of waters, and have seen my melancholy standing-place – could I but have seen her beloved form, what joy would have filled my heart! – but we were divided by the diameter of this immense globe – we were antipodes; but although the cold ocean, the snow-clad mountain, and a thousand dangers separated up, still we were as "one soul in a divided body;" there was a never-failing powerful attraction between up, superior to that power which attracts the mariner's compass; for although it exerts its subtle influence at an immeasurable distance, and with undeviating truth, yet when closely approaching the supposed object of its distant choice, vacillates, acts with uncertainty – its |

secret influence is lost, when we should have supposed it would have evinced redoubled power. I at length followed the example of my companions, rolling a detached mass of coral from the edge of the sea to the side of the fire, on which to rest my head. I reclined upon the sand, and notwithstanding the roar of the elements soon fell asleep, but during which dreams of a disagreeable nature continually harassed me, and I was in a short time entirely aroused by the voices of several persons near me, which I soon discovered to be my fellow adventurers, who had risen from their uncomfortable resting places, and were discussing the incidents of this adventure. The fate of the ship of course now formed the principal topic of their conversation; one supposed she had been driven a long way from the island while another stated that the typhoon had blown gradually round the compass, and therefore she could not at present be at any very great distance; still a heart-rending and melancholy foreboding hung upon us all, that she was lost! The last time we saw her she was drifting in the direction of North Island; we knew that great numbers of detached and sunken rocks lie about there, which cause the navigation to be extremely dangerous, and more particularly in a hurricane, when nearly all command of the ship is lost. The eastern part of the heavens now became slowly illuminated, betokening the coming day, the cheering sight of which lessened our melancholy and increased our hope. The violence of the storm had somewhat abated; the glorious sun was rising to light the mariner |

on his dangerous path, to dispel the darkness which adds much to his discomfiture, and to cheer him from his gloomy imaginativeness of being near dangers which he cannot perceive. The sun rose, appearing to spring out of the ocean, of a crimson hue; wild and tattered seemed the clouds which hung around him, gilded from his effulgence: he looked like a stern warrior rising from the fight, with his mantle torn and bloody, his enemies lying prostate and conquered, and encompassed with the darkness of night. Surrounded with glory, he rose from out of the dark roar of the elements with heaven-born majesty, securing by his presence harmonious peace, and giving to oblivion the horrors of the past night. The cheering light of day being once more fully established, myself and the mate commenced to climb up one of the rocky eminences which overlooked the sea, for the purpose of gaining, if possible, a view of the ship. After some labour, danger, and difficulty, we succeeded in gaining the uppermost pinnacle of the rocks, and casting our eyes around, beheld one of the finest scenes in nature. Below, the fluid element, uneven and broken, but losing rapidly the quickness of its motion – the giant waves slowly and lazily tumbling against each other, on account of the lessening of the wind, but the surf still rolling in enormous masses over the rocks, darting its snow-white foam in some places to a considerable height. In an opposite direction stood the tamana forest, imitating in its waving motion a gently troubled sea. But while we were both silent, and observing the different natural objects which quickly pre- |

sented themselves to our notice, with inexpressible joy we perceived the ship coming from behind some high land which stood upon our right, and she was soon fully in our view. A shout of exultation rent the air as we motioned to some of our companions who remained upon the beach, that the ship could be seen, and was near. They answered us with cheers, and rushing up the craggy rocks with dangerous velocity to the spot on which we stood, they feasted their eyes upon the object of our late solicitude with heartfelt satisfaction – some having deemed her lost, and others that she would not have made the island for several days. But our poor ship looked quite weather-beaten and dejected; here three top-gallant masts were struck; she was lying with only a close-reefed maintopsail to the wind, and as she lay tumbling and rolling, now on the top of an enormous wave, and now between two of them, appearing to be half engulphed, and ever and anon the sea washing over her decks, gave us a plain representation of the toilings and sufferings of the tars who had remained on board. The wind and waves continued to abate, and we employed ourselves in carrying the boat over a small neck of land, which divided the bay from another, and into which the ship appeared to be drifting. That glorious sun which gave us hope in the morning was now falling rapidly again into the abyss of night, but left us his evening rays to light us on our journey to the ship; and while we were climbing her side, amidst the congratulations of our companions, the magnificent orb was once more lost behind the dark and swelling bosom of the ocean. |

|

CHAPTER X.Having taken our farewell view of the Ladrone Islands, we still continued our course to the northward without anything remarkable occurring, except that on the evening of the 15th of April, being in the latitude of 24° 17' north, and near the Sulphur Islands, sailing at the same time nearly before the wind, we were overtaken by a violent squall, which carried away every sail that we had bent. In fact, it was the blast of a terrific hurricane to which this part of the world is very subject, but which only continued for about half an hour; and it was a fortunate thing for us that it was not of longer duration, as it is impossible to say where we might have run to; for we scudded before it at a frightful rate under bare poles, with our masts creaking as if going by the board every moment, and with a few fragments of the sails flapping about the rigging with awful force, which it was impossible to secure until the violence of the wind had subsided. And moreover, the thought which alarmed us more than any other was, that we were running directly towards land, which was not far distant, for we were certain that we had passed the Sulphur Islands, although we were well aware that we were near them; and even if we had passed them, we knew that the Bonins were directly in our front, so that we were |

all afraid of running upon them in the utter darkness which prevailed during the violence of the storm. But even if it had been light, and we had been so situated, with land in our front, I doubt very much whether we could have escaped the imminent danger of shipwreck, as it was impossible to steer the ship in any other course than directly before the wind. For even if the ship "yawed" in the steering one or two points against it, it appeared to increase with tenfold violence, and such was the horrid howling of the wind, the roaring of the waters, the clashing of the "backstays," creaking of the masts, and flapping of the torn fragments of the sails, that it appeared as if the demon of the storm was about to overwhelm and utterly demolish us with all his wrath. On the 21st of April, we again made the Bonin Islands, and on my first visit to the shore I busied myself in clearing a small space of land on the left of the large bay, which is situated on the south-west portion of South Island, for the purpose of planting some cocoa-nuts, yams, and bananas, which we had brought with us from Guam. I afterwards engraved my name in the bark of a large tamana tree which grew by the side of my plantation, as a frail memento of my visit. On our first arrival at the termination of this bay, we saw no less than upwards of a hundred large green turtle of the finest quality, lying upon the white sandy shore basking in the sun. Approaching the beach upon which they were lying, in the most cautious manner, we began turning them over upon their backs with |

the utmost promptitude, some of them requiring three of us to do so, and at the same time exhausting all our strength, their weight exceeding two hundred pounds. When we had succeeded in turning about twenty of the largest, the others became alarmed, and a scrambling race took place among the whole of them to gain the water; in doing so they threw up the sand upon which they lay with their fins with great force, and when they got to the edge of the bay in shallow water, those we captured in that situation gave us some trouble. This was especially the case with the last that we endeavoured to obtain, one of exceeding large size; for as it had gained a sufficient depth of water nearly to cover its shell, it was just on the point of darting off with great velocity, when at that moment one of our men endeavoured to stop its career, but was directly thrown down by the violence of its action; however, three more of us immediately ran to the spot and assisted in the capture, when a ludicrous scene presented itself. The turtle having got into deeper water, was exerting itself with all its strength to escape from our grasp, and in doing so two of us were thrown backward into the water, with our antagonist on the top of us; our friends, on the other side, exerted themselves to their utmost to relieve us from our unpleasant situation, with just our heads appearing above the surface of the sea, and during this time our obstinate adversary kept moving its four fins with the greatest velocity and force, dashing the salt water in our faces, almost blinding us, and at the |

same time affording every now and then some very awkward thumps with its flippers. We could not forbear, when we thought of our strange rencontre, breaking out into an immoderate fit of laughter, which had the effect of decreasing our strength and destroying our vigilance, so that the turtle at this moment making another violent struggle, broke from our hold and escaped, leaving us covered with sand and drenched with water. However, when we returned to the shore, we found that we had secured above forty of the finest, so that we had no reason to regret the loss of the one that had escaped. After having placed two of the largest in our boat, we set about returning to the ship, leaving the others secure on the beach. But while we were passing through the bay, we observed an immense number of large sharks and dog-fish, with enormous sting-rays, or "devil fish" which last are formed very similarly to the common fish known by the name of skate, only much larger, being from five to six feet across, the posterior angle of their flat bodies ending in a long tail, which gives them a remarkable appearance. These curious fish were very shy, for the moment they saw the boat they set off in a great flurry out to sea, using their immense flaps through the shallow water, as a bird uses its wings, leaving a "wake" after them like a steam-boat. But as for "Master John Shark," as the sailors sometimes term them, they were not to be intimidated in the least by our appearance, in fact they frequently came close to our boat without evincing the slightest concern. The dog- |

fish also expressed the same unwillingness to be disturbed or alarmed, appearing to be quite occupied by their anticipation of the rich harvest which awaited them in the feast of young turtle to which they were hourly looking. For we found on the beach I have before mentioned, several large holes dug n the sand, which had been prepared by some of the turtle to deposit their eggs in; after having done so, the sand is again removed, and carefully placed over them, they are then left to be hatched by the heat of the sun. As it was the hatching season at the time of our arrival here, all these sharks, sting-rays, and dog-fish, were waiting at the edge of the bay, to devour the newly-hatched turtle as they made their first entrance into the water, which they do as soon as they can relieve themselves from the sand with which they are covered; so that, considering the number of sharks, devil-fish, and dog-fish, which we saw in the bay, and knowing well their gluttonous propensities, it was astonishing to me how it was possible for a single young turtle to escape. All the next day we were well employed in getting on board the remaining turtle we had left on the beach on the preceding day, and by night-fall we had finished our task. For the space of four or five weeks afterwards we lived in excellent style, our dinners surpassing a civic banquet in the quantity and quality of our turtle-soup, our black cook thinking very little of fifty or sixty pounds of their flesh, with its "green fat" and "calapee," for the preparation of his dinner – which daintly fare con- |

tinuing so long, we became quite aldermanic in our appearance, and even our dogs and cats, which fed upon their waste morsels, soon became remarkably corpulent, seeming also to get quite idle, and excessively stupid, verifying the words of our great poet, who states that "fat paunches make lean pates, and dainty bits serve to banter out the wits." Having touched at North Island, we visited the grave of Captain Younger, who was killed by the falling of a tree while on this island, which misfortune was quickly followed by the total wreck of his ship, on the rocks not far distant from the spot at which, only a few days before, he had been interred. While there, three of us entered into the spirit of wild-pig hunt, which was amusing and romantic enough in these desolate regions: many daring and curious feats were performed on that day, the particulars of which would fill a chapter, but I can only state that we captured three fine boars. We now began cruising about these islands for whales, but met with very trifling success, and finding that it was not likely to be improved on account of having lost our two best whalers, and also finding that the captain still continued his ill-treatment of the crew, which had been the principal cause of our misfortunes, I could not help turning from the scene with disgust, and a strong desire to return home sprang suddenly up in my mind, which I could not control, and which I certainly had no inducement to repress, for the captain had by this time estranged from him every soul in the ship, by his cruel and tyrannical conduct. This being the first and last voyage I had ever under- |

taken, the very enjoyments of the sailors at times appeared to me to be sufferings, when I compared London associations with things which take place upon the great sea. But when I saw thirty-two good, industrious, and harmless, though brave men, abused and browbeaten to a most shameful extent, by a mean and contemptible tyrant, while at the same time they were exerting themselves to their utmost for the success of the voyage, which he had himself frequently neglected to do, I turned from the scene with horror, and plainly intimated that I could no longer endure the sight. Can we wonder at some of our men deserting us? I have heard of seamen escaping from ships which have been tyrannically governed, although they have been twenty miles from land, merely using a piece of bamboo to assist them to swim on shore; others in their despair have thrown themselves among savages. They have precipitated themselves into the sea! they have at times turned against their inhuman task-masters – they have mutinied – they have destroyed their oppressor in some instances, in consequence of the ill-treatment they have received and endured, until the passions in their vehement reaction could no longer be shackled or kept down. Such was the captain's conduct that I now made up my mind to seize the first opportunity of leaving him to his fate the moment I could find it convenient, whether advantageous or not to myself, and on the first of June 1832, being still off the Bonin Islands, we had the good fortune to fall in with the Sarah and Elizabeth |

of London, Captain Swain, which belonged to the same owner as the ship I was then in. When I informed Captain Swain of my desire to return home, he in the most handsome manner offered me a passage in his ship, for which kind offer, under all the circumstances with which we were then surrounded, I shall never cease to feel grateful. On the same day that I have just mentioned, I exchanged berths with Mr. Hildyard, who happened to be surgeon of the Sarah and Elizabeth, and with whom I had been acquainted in London, he having studied at the same medical school in which I was also engaged. He entered the berth I had left by his own urgent desire, but much against my wishes and best advice, and which afterwards he had much reason to regret. But fate appeared to order the exchange, which was greatly to my advantage, and at midnight, it being calm and convenient, I was conveyed to the Sarah and Elizabeth with the whale-boat that I was in so completely filled with curiosities and shells that the oars could not be used, so that the men were obliged to make use of paddles instead. On the dark ocean, at midnight, I took my last farewell look of the noble but ill-fated ship, which had carried me safely through a thousand dangers. We had weathered them together, we had travelled together at least twenty-five thousand miles! And now in my separation from her, the tear that bedimmed my eye made me think that she was almost a thing of life. The brave seamen who had sailed with me from London, and who were still doomed to remain on board, saw me |

leave them with regret; all of them would have followed me, but it was impossible: such is the effect of tyranny that they would have abandoned the captain to his fate, but they had no door by which to escape. After I had left them, they commenced the Japan fishery, but obtained only a small quantity of oil; they then went to the coast of California, and there they met with the same ill success; the ship then sailed towards the equinoctial line, and there they lost the source of all their misfortunes – the captain died, and his corse [sic]was committed to the great deep, "without a mark, without a bound." The people who remained on board obtained but little oil afterwards, because they had by this time been out so long that the provisions were getting scant, their rigging and the ship also were getting in a dilapidated state. The men who were left on board, for by this time many had forsaken her, were completely dispirited, their conjoined cry was for home! To which they endeavoured to get as fast as the condition of their sails and cordage would allow them. And after they had put the owner to an enormous expense, touching at one place and another as they sailed along, finding it necessary to do so, they at length were fortunate enough to arrive at the port whence they sailed, after an absence of three long years and a half, during which time they had only procured one-half of an average cargo. |

Thomas Beale, 1807-1849Thomas Beale, an Englishman, was born in 1807. In 1830, at the age of 22 or 23, he sailed for the South Seas as a physician on the London whaling ship, the Kent (William Lawton, captain). On June 1, 1832, Beale exchanged berths with a Doctor Hildyard while both vessels were near the Bonin Islands. He then returned to England on board the Sarah and Elizabeth (William Swain, captain) in February, 1833. In 1835 Beale published for subscribers a fifty-eight page booklet with a long title: A Few Observations on the Natural History of the Sperm Whale, with an account of the Rise and Progress of the Fishery, and of the Modes of Pursuing, Killing, and "Cutting In" that Animal, with a List of its Favourite Places of Resort (London, Effingham Wilson, 1835). The apparent success of this fifty-eight page publication, led Beale to revise and expand it in the more substantial The Natural History of the Sperm Whale: its Anatomy and Physiology – Food – Spermaceti – Ambergris – Rise and progress of the Fishery – Chase and Capture – "Cutting In" and "Trying Out" – Description of the Ships, Boats, Men, and with an Account of its Favourite Places of Resort. To which is added, a sketch of a South-Sea Whaling Voyage; Embracing a Description of the Extent, as well as the Adventures and Accidents that Occurred During the Voyage in which th Author was Personally Engaged. (London, John van Voorst, 1839) which was published in 1839. Joan Druett, in Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail (Routledge, New York, 2001) writes of Beale:

Beale's Natural History was used by Herman Melville as a fundamental source in the writing of Moby Dick which was first published in 1851.

Tom Tyler, Denver, September 27, 2002

Rev. Feb 11, 2017 |

|

Source.

Thomas Beale.

Selections were made from the Whalesite Anthology of 19th century whaling.

Last updated by Tom Tyler, Denver, CO, USA, Nov 4 2022

|

|