|

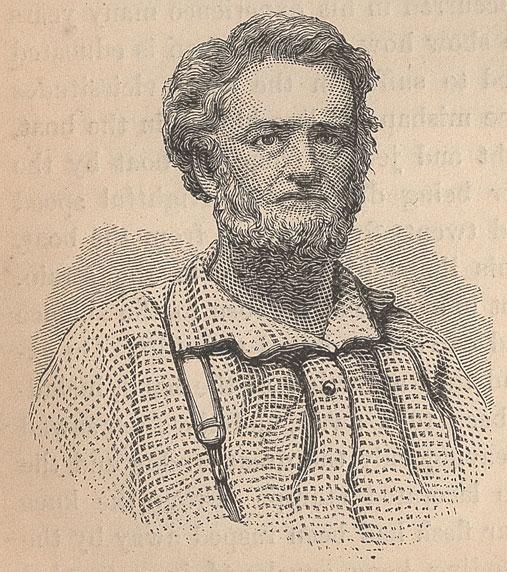

William M. Davis 1815-1891 |

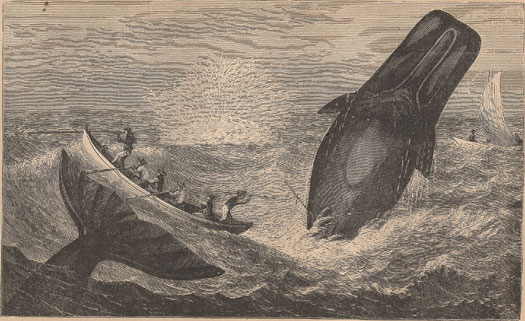

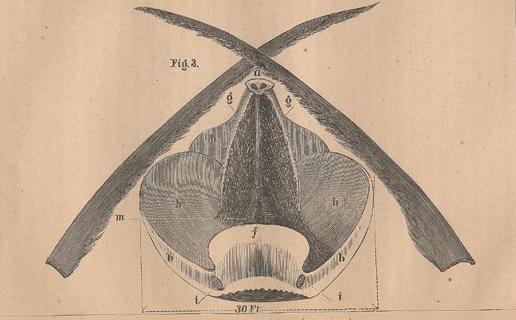

IN THE WHALE'S JAW. |

|

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

Harper & Brothers, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. |

CONTENTS.

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

ILLUSTRATIONS.

|

transplanted in America, struck deep root, and brought forth a rich harvest from the sea. The first recorded agreement concerning the capture of whales in America commences in this wise: "Ye 5th day of ye 4th month, 1672. James Loper doth ingage to carry a design of whale-catching on the island of Nantucket. That is to say, James ingages to be a third in all respects, and some of the Town ingages on the other two-thirds in like manner, etc." Behold in the wonderful history of American whaling how great a flame this little spark kindled. The practical mother-wit, or gumption, which characterized the early American found expression in this first adventure in this most perilous profession. In this agreement we find that subdivision in interest, that co-operation of capital, skill, labor, and courage which ultimately secured a prosperous career to the Americans, made them masters in the business, and drove the men and ships of all other nations from the whale-fishery. Just two centuries from the date of the above contract, or about "ye 5th day of ye 4th month," 1872, my good angel wrote to me, saying: "Overhaul your journal of a whaling voyage to the Pacific, and give us a history of American Whaling by pen and pencil. Fling yourself into the work; write of that strange life as you saw it from the forecastle and the mast-head, from the boats and the quarter-deck. Put into it all the poetry and rapture, the danger and the deviltry, the enjoyment and the suffering, with all the history you have in your memory or have access to. To be statistical and tedious is a felony; but history can be made as charming as romance, without losing any of its value." Such were my directions, and, sailing by that chart, I open the old oil-stained pages of my journal, and therein find that on the 11th day of ye-10th month, 18-, I, Bill Seaman, |

"BEEN ABOARD THE CHELSEA YET?" |

bow-oar with divers others, including captain's mates and harpooners, did "Ingage to carry on a design of whale-catching" in the Atlantic, the Pacific, and all other waters to the uttermost ends of the earth, wheresoever whales did swim; and "some of the town of New London did ingage with us in like manner, in proportions" as set forth in the ship's articles of the good bark Chelsea, Major Thomas A. Williams, owner. And here, before I begin my narrative, I wish to bespeak indulgence toward one of its features. It is based on the well detailed journal of a foremast-hand, who rose to boat-steerer; therefore it is written from the stand-point of the forecastle, and the quarter-deck is treated of as an object of a laudable ambition. My journal is used as a cord on which are strung the experiences and adventures of others, such as I have been enabled to pick up in the form of yarns on board the Chelsea. Omitting a date to my voyage, I am thus enabled to give the experiences of a quarter of a century. About the internal economy of our ship I write as the boyish sailor; and I ask you old captains, in imagination, to sit barefooted on an old sea-chest as you read my story as I sat to write it. Is it necessary that I should recount how complaisant the major was before I signed the ship's articles? It appeared that the major was anxious to fill up his crew, that the vessel might not be detained when her fitting was completed; and doubtless, as he regarded the tall, slender, and rather weakly youth before him, he deemed it necessary to throw in an encouraging word to strengthen good resolutions. "Ah! you're from Pennsylvania. Very good place that: a little too far from salt-water to be wholesome, I guess. Salt air will soon put color in your cheeks. You think you'll like the sea? of course you will. Nice life – very, if you take to it right. Been aboard the Chelsea yet? Yes; good ship the Chelsea, and such a sailer! A regular Baltimore |

clipper; easy times aboard that ship. You've trade-winds most of the way to Cape Horn: trade-winds, you know, are steady; as fixed, sir, as the needle to the pole, as the poet has it. And then there's the Pacific! Grand sea that; all about Juan Fernandez, Magellan, and the Southern Cross it's as calm and smiling as a mill-dam – so smooth that the illimitable sea seems a boundless oil-tank; where you see reflected in it the belt of Orion and the Pleiades. The thought almost tempts me to run out on a voyage, just to see that whaleman's heaven. "Do you know that you get fresh beef at sea? Yes, sir, you do. Porpoises are to be had for the catching. Porpoise has muscle in it; you'd stiffen up on porpoise. And albatross too, big as geese; a little oily, but you'll get used to that. It makes a man water-proof to eat albatross." The good man never dreamed that this moment was the fulfillment of the dreams of my short life. When I was a little boy, I had rigged and sailed my toy boats; and when a few years older, I had devoured Cook and Delano, and was happy in the library of Mavor, looking forward to the time when I too should visit the strange seas and scenes I had pictured in imagination. I took joy in the major's persuasions, as I knew that he would accept me, and allow me to go in his ship. Let me say it was no freak of a child, no sudden whim, which led me to this point. Twice I had been disappointed in going to sea. Once I had shipped in the Globe, East Indiaman, when a severe accident kept me confined for weeks after she had been under way. On a bed of sickness my young heart followed that gallant ship on her course, and I found consolation only in the promise of my fatherly brother, that when well another berth should be found me. Then I shipped on board the saucy little free-trader, Star, bound for the coast of British India. She was armed, and |

carried a very heavy crew. My kit was purchased and taken on board, and one drizzly dark morning I went on board in my gay shirt and spotless ducks. When examined by the surgeon, he pounced on my wrist, left crooked from fracture in the late accident. It was still tender: he gave it an awful wrench; I flinched. "You won't do," was his awful verdict. In vain I told him that it was getting well very fast, and would soon be as sound as the other. He saw my heart was in going, and, being a kindly man, he said, "I can't pass you as sound; but go on shore now, and thank God that a weak wrist stands between you and this voyage." I did not know what he meant, but I went home to the quiet country almost heart-broken; and had no peace of mind until a letter from my friend, Mr. Lorenzo Draper, of New York, brought the glad tidings that he had secured a place for me on the Chelsea. And in a few days, with great joy in my heart (for which God forgive me), I kissed the tearful faces which bade me farewell for the long and, to them, fearful voyage which lay before me. Little did the good major know how little I needed the kindly encouragement he was extending; and lest I might again be disappointed, I made haste to append my name to the articles. "Ah! you've signed. That's a good Bill; there's a captain's berth ahead, if you earn it. Now run down to Mr. Strong in the basement; he'll finish your outfit in a jiffy. Take good advice: he is as sharp as he's Strong; make him take off fifteen per cent. for cash: he will get rich faster than you or I at that. Get a good outfit; spend your money for clothes, and not for tobacco, so that you may keep clear of the slop-chest. You have a week before you sail: look about you, and make the most of New London; for a three years' voyage is no trifle, and you won't see a better place the other side of the land. Good-morning." I did not again speak to the major for forty-five months. |

Eight days afterward, I was standing, a cold, wet creature in red flannel and duck, looking back at a low bank of cloud-like land, as Montauk Point was fast sinking from sight.

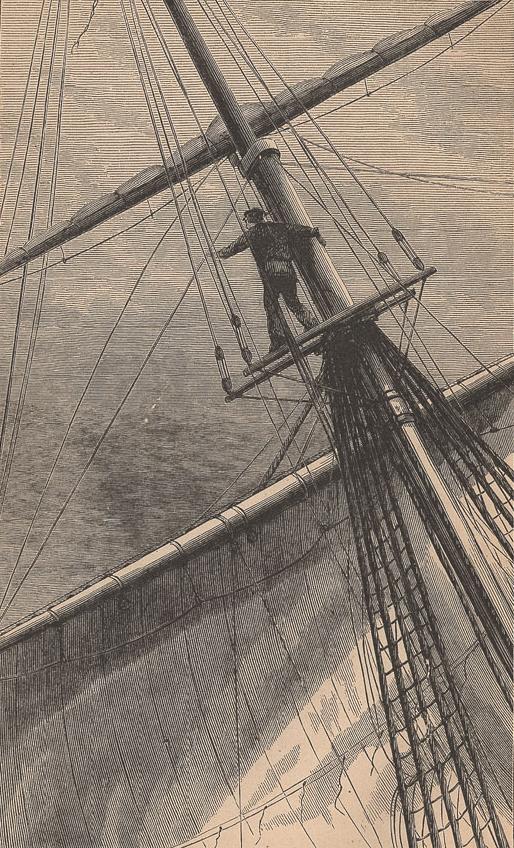

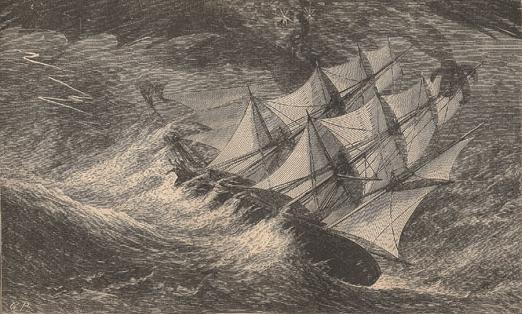

It seemed a wide Rubicon I was crossing. Heart and landscape sunk together. I was now in fitter mood to bid a proper good-bye to those I had so lightly left, so lightly thought of – bah! what a miserable substitute is the rough flannel cuff for a linen handkerchief: it leaves the eyes so red that the jolly brutes about me, in sympathetic tone, inquire if my "head is running on shilling calico already." The first night at sea is ever memorable, especially when a stiff north-west gale whistles a double-quick over the starboard quarter. Such was our welcome; but running free, we made good progress on a course. By some mysterious election I found myself in the starboard watch, Mr. S––, the second mate, heading it. I very soon found a prejudice against my superior, and a serious doubt arose as to the right of his claim to be a gentleman. The matter came out in this wise: in the course of his duty, I suppose, it became necessary to order a reef in the foretop-sail. The yard was lowered away; the reef-tackles hauled out, with much unnecessary "Yo, heave oh'ing," and the old salts flocked up the weather shrouds. I was deeply interested in their movements, never suspecting that a green hand would be required to go aloft the first night out, and in such rough weather; so I studied the endless tangle of braces, halyards, reef-tackles, clew-garnets, falls, and purchases by which I was surrounded. I wondered at the strange music of the storm-harp, the infernal confusion of creaking yards, the flapping of the sails |

away overhead: all this was food for the mind of the lad fresh from the little saw-mill quietly nestled in the shelter of the Gulf Valley. But presently, as I held some secure rope, admiring the agility with which the sailors squirmed out of sight into the whistling, howling darkness overhead, I saw the mad second mate coming for me with a rope's end in his hand, and with some ugly expletives, in sea lingo, between his teeth. I took in the whole situation in a moment, as S– again yelled to me, "Lay aloft, and reef top-sails, you infernal lubber!" The turmoil and confusion of the gale had subsided before this new storm came, and unhappy I found it comparatively easy to creep up the ratlines. My pride then led me to avoid the "lubber's hole" and to mount the terrible futtock-shrouds. Here, in some way, I found myself close in to the bunt on the weather foretop-sail yard. The roll, pitch, and sway of that yard, and the gyrations of the foot-rope supporting me; the darkness, wet, and howl, the hoarse orders and naughty oaths of the men, banished the little sense which the premonitions of sea-sickness had left me. I wonder if any sailor ever forgot his first reef at night. I don't remember to have knotted a point. In sheer desperation I hugged the shivering spar, repeating the beautiful prayer, "Here I lay me down," etc. I was very loath to let go, and even allow the impatient sailors to lay in from the yard-arm. "Goodness gracious!" thought I; "can I ever go clear out on that yard in such a night?" By some means all hands got safely on deck, all was bowsed taut, and we stood on our course again. For the remainder of this miserable night we were hauling and letting go, belaying, making fast, coiling, reefing, and furling, and doing many things which I never so much as heard of in the whole twenty-seven volumes of Mavor's voyages. The pitch of our little uneasy bark, the spraying seas which over- |

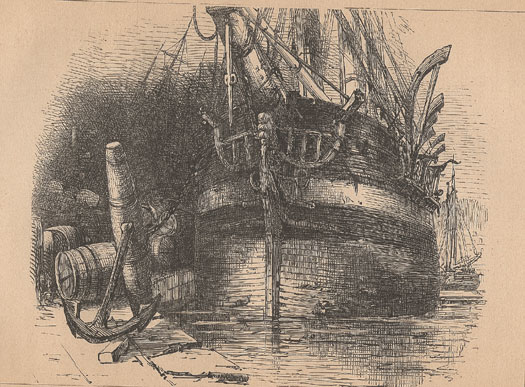

leaped our low bulwarks, and the growling oaths of moist humanity grew worse and louder, until I thought we were in for a terrible gale, and would have so described it, had I not overheard an old salt remark that it "blowed a stiffish breeze." Then I took courage and thanked God, though I should have preferred, with Paul, "to land at the Three Taverns" to do it. Such was the opening of the young landsman's journal of a voyage round Cape Horn in a three years' cruise for sperm-whales, Captain B–– commanding. In passing, let me state that, as the names of our officers are not material, I omit them for reasons which will appear hereafter. If you follow me through the rest of my wanderings, it is proper that you should know and love the good ship which bore us. She was beautiful and good – beautiful in the calm, swift in the breeze, and staunch in the storm; sharp as a clipper; graceful in every line as the frigate-bird; wide-spread in wing as the albatross; and, in riding the waves, like a Mother Cary's chicken. She was sharp in the bow, broad in her beam, and clean in her run; small in her hold, with broad and roomy decks. A woman's head graced her cut-water, and half the gods of heathendom, in alto-relievo and high colors, decorated her stern. In fact, in rig and hull she was a prince's pleasure yacht, rather than a blubber-hunter, although she was built expressly for such service. "Give her speed," was the major's order; for speed in a whaleman is as wisdom was to Solomon – it includes all things. She had the proud habit of the blood-horse in tossing her beautiful head in the face of a gale, and if the martingale was not of the truest and strongest she would toss her jib-boom over the top-sail yard. Then she would nestle her woman's head so deep in the bosom of the leaping waves, that the foam of their crests would kiss the feet of her master on his quarter-deck. Gay and lively, brave and |

safe, was my old pet and mistress; for I came to love her in my long life of safety aboard her. Our ship, bark-rigged, and registered 400 tons, could stow 300, equivalent to 2400 barrels of oil. We carried four boats on the cranes, and three spare boats on the spars above the quarter-deck. To each of the four boats was assigned a crew of six men – viz., a boat-header, a harpooner, and four oarsmen. Besides the twenty-four men assigned to the boats, we had a carpenter, a cooper, a cook, a steward, a cabin-boy, and three spare men; or thirty-two all told. The captain, cook, steward, and cabin-boy did not stand regular watches; they aided as ship-keepers when the boats were off. This gave the starboard and larboard watches each fourteen men, sufficient to handle sails in nearly every emergency. The crew was composed of a captain; a mate, who headed the larboard watch; a second mate, who, with the third mate, headed the starboard watch; four harpooners, and the trades mentioned before, with greenhorns and old salts, who were known to be, and shipped as, able seamen. The strong force on board a whale-ship and the duties in the boats give an importance to the under officers unknown in the merchant service. With us the second mate was the officer of the deck during his watch, and he never left it to furl or reef: he exacted as respectful an "Ay, ay, sir," in answer to his orders as did the captain himself. The harpooners were divided, two in each watch, save when we were on cruising grounds. Then we reefed down every night, and each boat-steerer headed his own boat's crew's watch during the night, and became officer of the deck. Our outfit consisted of extra sails and rigging, spare spars, and a store of tar, paint, etc., for repairs to ship; cedar boards and light timbers for the boats; a large quantity of admirably made whale line; a store of harpoons made of |

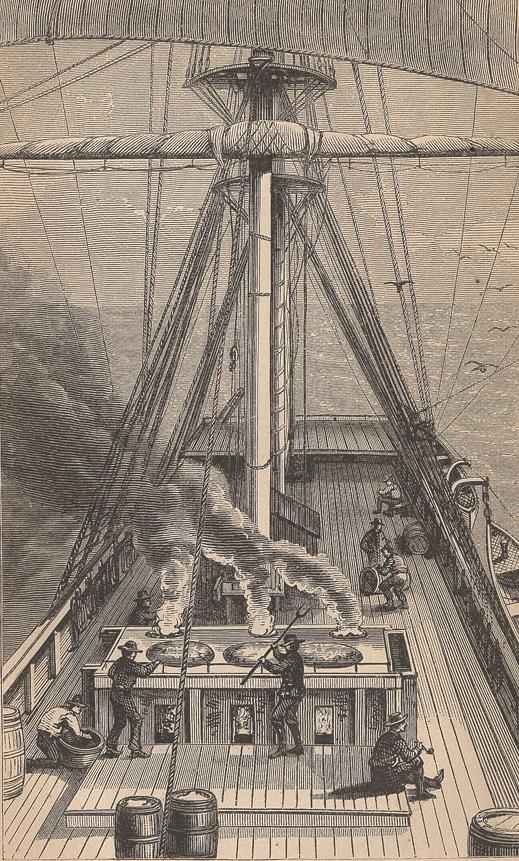

the softest and toughest iron, with lances of a quality of steel and capacity of cutting edge that might excite the envy of a diplomaed "sawbones;" also cutting-in spades, boat hatchets and knives; casks for the oil, stowed with water, food, or clothing; and all the very many necessaries to cover the wear and tear of long years of arduous service. An important and peculiar feature in the equipment of a whaleship is the "try-work." This consisted in our ship of three large iron pots, built in brick-work, and so supported by iron stanchions, that a body of water was maintained between the hearths and the deck to intercept the heat of the furnaces. For stores we carried as a staple, ship-biscuit, pork, and beef, with coffee, tea, molasses, rice, beans, Indian meal, flour, and pickles. Our worthy major was a professor of religion, and I am quite sure that on the day of final account he may safely call upon the Chelsea's crew to testify to his liberality in our outfit. We might confuse the accountants if we gave our entire list of luxuries, which included "doughboys," "choke-dog," "lobscouse," "dough jehovahs," and "menavellins." Each day of the week some one of the above delicacies accompanied the inevitable salt-junk; and, believe it who may, we had pork every day, not two or three days a week, as some unfortunates have it. Furthermore, access to the bread cask and the molasses tank was never denied: Perhaps there is no single article, I may say in parenthesis, in which the superiority of the American whaleman's outfit is more manifest, than in the excellent ship-biscuit which all carry, the greatest care being taken to exclude dampness or decaying influences. It will be noticed at once how well we were provided for. |

CHAPTER II.

The whale-killing historian and poet, Obed Macy, says very truly, that "The sea to mariners is but a highway: to the whaler it is his field of harvest; it is the home of his business." The passage, or voyage, to the harvest-field occupies little of the mind of the whaling man; it is to the harvest-field itself that his thoughts turn. Green hands, women, and men-of-war's men may find material for a journal and a book, mayhap, in the incidents of travels about the blue sea. But the whaleman steps on board his full ship, bound home from Behring Strait, and battered and rusty from a four years' cruise, with the expectation of no more noteworthy incidents than a tired bank-clerk might encounter in a voyage from the Chestnut Street wharf, Philadelphia, to Camden, via Smith Island Canal. I was verdant, and the old journal was well filled before we reached the Brazil Banks, via the Cape Verds, which we sighted and passed. The notes taken were mainly personal, however, and immaterial to this history, except, perhaps, one referring to the captain's inaugural speech. In this speech there was the stereotyped bluster, threat, and insult deemed necessary to place the captain and officers in their proper places, and to put the crew in sailing trim. We were duly informed that |

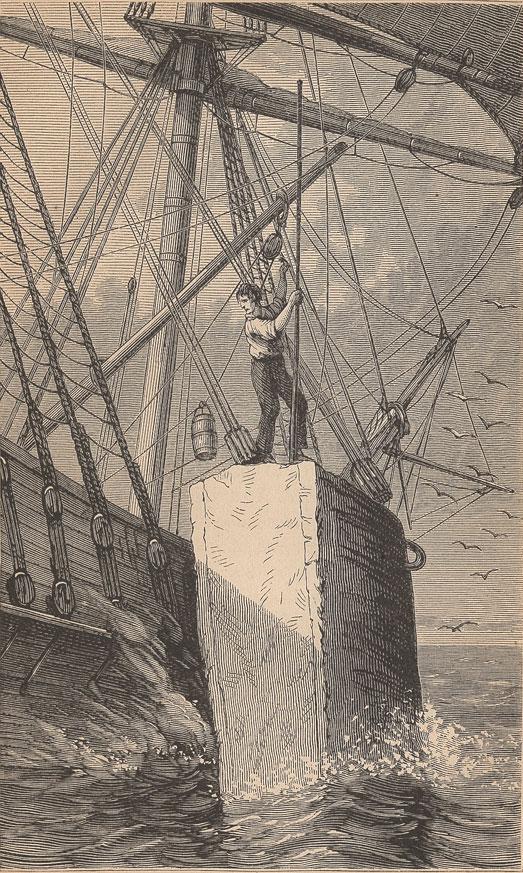

the captain was to do all the fighting and swearing on board the Chelsea. Green as I was, the deprivation of these two sea luxuries was of small account, but some of the old salts took it greatly to heart. To stop the grog on board our whale-ships is of slight moment, but "to clap a stopper on honest swearing is a lubberly go," was the general verdict when the men went forward. Very soon after leaving home the mast-head lookout was established. This consisted of an officer, or boat-steerer, at the main, and one of the crew at the foremost top-gallant cross-trees or royal yard. The mast-head was manned at daylight, and continued until sunset, and was relieved every two hours, the crew taking the watch, as they did the helm, strictly in turn. We were assigned to our places in the boats. I was placed at the bow-oar in the starboard, or captain's boat, in which position service was likely to be seen, as Captain B–– was an ardent whaleman, skilled with the lance, and proud of helping his mates out of a tight place by pitching his lance into the life of their whale. Our boat-steerer, Elisha Chipman, was a fine specimen of manhood, as will appear hereafter. At times, when the ship had moderate headway, the boats, with their green crews, were lowered, and we manoeuvred around a dummy whale – a spare spar towed astern. Thus we were continually drilled in lowering away, shipping oars at the word, "pulling in chase," "going on," "starning," "pulling two oars starn three," until our hands were sorely blistered, and something like discipline was established among the crews. Now we were fairly launched on our cruise, and the captain was ready for whale. The injunction was given to keep our "eyes skinned at the mast-head, and sing out for every thing you see." And thus we ran through the tedious calms and sudden squalls of the "line" into the south-east "trades," which blew us to the Banks |

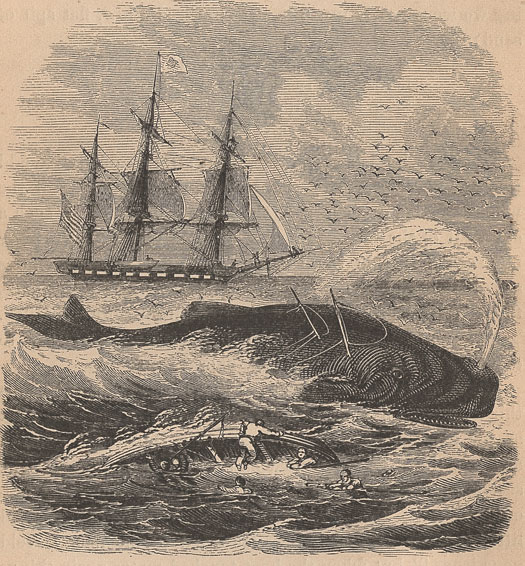

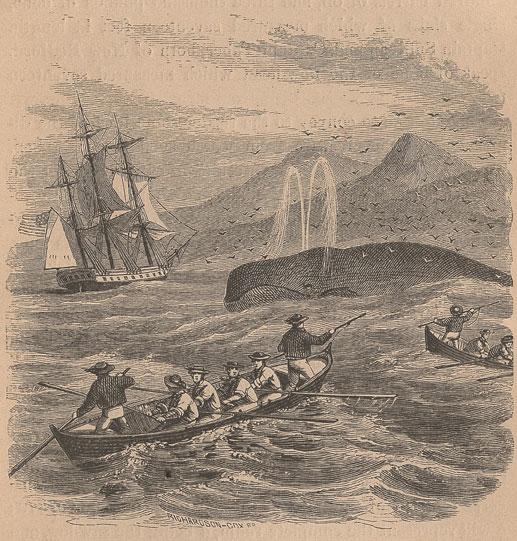

"THERE SHE BLOWS!" |

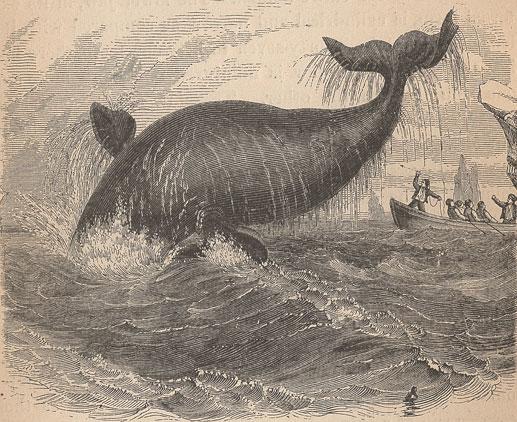

of Brazil. One day the cry came from aloft, "There she blows!" "Where away?" shouted Captain B––, his gray eyes snapping with excitement. "Three points off lee bow; blows; blows; four miles off, and sperm-whale." All hands were now alive, the watch from below came on deck, the captain sprang aloft, and a long-drawn shout came from above, "There goes flukes!" as the whale went down. The excited crew were in the lee rigging, keeping a sharp lookout, the boats having been cleared for lowering. The captain ordered the maintop-sail aback. "Stand by to lower," he cried. "There she blows, close aboard." The boats were awkwardly launched, the willing crews tumbled in, and great confusion of oars ensued; but in good time we settled down to the work, and were fairly off in pursuit of our first whale. A long chase it proved, and fruitless, although we had two fair darts. The mate's boat was first on, and ours was second; but the hump seemed under my bow-oar as we ranged across the corners of his flukes. Owing to want of nerve, or awkwardness in the crew, however, the iron dart came back straight; and so this fine whale was left in the South Atlantic, to blow in peace. The captain took his failure in good part, and scolded less than we expected. The evening's watch was an excited one. As hunters track back on the sport of the day, so we sought reasons for our failure. The knowing ones were wise about spermaceti, and we green hands learned much of forecastle natural history in the evening's recital. Every mother's son who had ever gone on to a whale had a yarn, and some of those told were indeed "wonderfully and fearfully made." The enjoyments of the voyage – these I will describe, as they show something of a whaler's life – in no slight degree depend on the crews having some one skilled in the violin to stir the dance on calm evenings. Generally the accomplish- |

ment is considered necessary in the "doctor" (i. e., cook) of the ship; and if the cook is a black, the chances are that a fiddle is stowed in his sea-chest. We had a beau ideal "doctor" and fiddler, and his enlivening medicine went far to banish scurvy from the ship. The second in importance is the "minstrel boy." He must have considerable range of expression, that he may sing of love, war, and the storm; to soothe us with the sentimental and cheer us with the comic. He must sing with Castillego:

Or, with Dibdin:

Touching on the known constancy of Jack, and the temptations of this wicked world:

He will shock our native modesty by singing of the sights prepared in the ballet:

He sings the joys of virtuous love thus:

|

And of the sterner duties of our hardy profession:

If need be, he must, handspike in hand, mount the windlass and, in deepest bass, lead the chorus,

In brief, the "minstrel boy" must have a fitting song for all moods and every occasion. He is an attraction in the carouse on shore, and in the night-watch in calm and storm. Such a treasure we had in our mulatto boat-sterner, Harry Hinton. Brave and faithful, he never shrunk from a duty below or aloft, or a danger in boat or port. He stuck to the Chelsea through good and evil, and was one of the six who remained to drop anchor from our old ship in New London harbor. The sailor is an insatiable lover of the yarn, and his passion is still strong after he has put aside his sea-legs and settled in the peaceful home, away from the blue water. The marvelous narrations of the forecastle and the quarter-deck have as wide a range as the songs. One of our crew had mastered Mavor's voyages, Walter Scott, Cooper, and Marryat; and being blessed with a memory that held all the wonderful and beautiful of his earliest readings from the "Good Book," he was able to hold the watch in breathless attention through many bells – now with the matchless story of "Ivanhoe," now with the "Talisman," now with "Peter Simple" and " Snarleyow," or with the adventures of the old terrors of the seas on which sailed the English buccaneers. The wild extravagances of Hackett's Nimrod Wildfire and Forrest's Metamora were recited in minutest detail, regard- |

less of time, as Time was an enemy to be led captive by the cunningly meshed yarn. "Come, Jack, now for a long yarn," is the request of the watch, as we gather about the windlass and the forehatch. "Oh, Lord bless your souls! I haven't time for a long yarn, as it's my trick' at the helm at four bells." "You don't get out that way, Jack;" and some one agrees to take Jack's trick, so that he has a clear three and a half hours to drone over an old-fashioned yarn, the requisites being that it shall be of "love and fun, with some murder in it" – the more improbable the better. Jack consents, and is conscientious enough to stretch the yarn out to eight bells, as per contract. Should he find himself, at the end of half an hour, ahead of time, he resorts to an expedient worthy of a professional novelist. The hero is taken home, and friends crowd around him anxious to hear his latest adventures. Jack refreshes himself from a black bottle, and boldly repeats the yarn he has just told us. We then lay awake to watch that his memory is perfect, and that he does not trip, or omit the slightest detail. Should he do so, he is at once stopped, to account for the kink we have detected. If he makes many slips, the impression becomes general that he has been playing on our credulity. This is pretty sure to breed a row, to be settled at the first port we make, as Captain B–– will not allow any fighting on board. Thus we are thoroughly awakened, and in great good humor we strike eight bells and call the larboard watch. The theories and philosophy of the landsmen are accepted with a very liberal discount by forecastle savants. "How could those lubbers ashore be expected to know the real facts of deep water, when they squat ashore and take the dead shells and waifs which the live sea tosses to their-reaching hands? A dead whale floats ashore, and they make drawings that would stand as well for a Dutch galiot, and put it |

in their picture-books as one of the living, beautiful facts of God's creation!" Reasoning much in this way, Jack takes a landsman's theories with a grain of allowance, deciding that much learning tends to madness. His own philosophy is sometimes astonishing – certainly original; and I may cite the theory of the Gulf Stream proposed by Mr. Burrows, our Mexican third mate, as an example. He started our greenhorns on a new track, by declaring the old theory of a concentration of Atlantic currents insufficient to account for all the phenomena attending this stream, and also that the influence of the north-east trade-wind blowing into the Gulf of Mexico was incompetent to produce such a result; for, said he, the violent interruptions of contrary gales and hurricanes would not affect the general velocity or volume of the stream. "The fact is," said Burrows, very learnedly, "there is an under-ground channel between the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico, through which a great river of the warm water of the Pacific is poured to the lower level of the cool Atlantic. In evidence, the pretty weed which floats in great fields in the Gulf Stream is found growing on the Pacific shore of the continent, and not on the eastern side. To be sure, great masses are met north of the islands, but it is the bruised, half-killed weed which has passed north in the stream and has been swept into the great return eddy. The little crabs and the peculiar creeping fish found in the weed, belong to the Pacific shore. But the best reason is the fact that whales do pass from sea to sea in a time too short to allow of the long journey around Cape Horn. Whaling skippers tell of sperm-whales that have been killed in the Pacific carrying in fresh wounds the bright irons bearing the stamp of ships then cruising in the Atlantic. On after comparison of the logs, it became apparent that but few days elapsed |

between the escape of the stricken whale in the one sea and its subsequent capture in the other." The interest in this view lies in the existence of the interoceanic canal; but the sperm-whales are close-mouthed (as we afterward learned), and keep their own secrets. One of the men remarked that the idea was "too simple and rational to be believed," and he went into a scholarly yarn on the subsidence of a great part of our continent, the lofty fingerprints of which he said yet remain visible in the mountain heights of Cuba, San Domingo, and the chain of the Caribbees. And he told of a civilization in this Western World older than the Pyramids, and in existence before the learned Brahman Menou recorded, in Sanscrit, the dawn of human history. But the incidents of the day indisposed us for subjects so scientific, and all knowledge concerning the Gulf Stream was voted a whaleman's yarn. Old Ben, one of our crew, was then called on for his yarn about the first time he went on a sperm-whale. This story was as nuts and cider to the green hands, inasmuch as it was an honest confession that an old hand had been "gallied" (frightened). The fellow-feeling made us wondrous kind. But you should know Ben Coffin in order to appreciate the fun of the story. Ben, in his youth, might have sat for the picture which Dibdin sang:

Ben, as he begins, says he is a rich farmer's son, and that he came to sea to wear out his old clothes. When he gets through with the job, he is going to play the role of the Prodigal Son, and go back to the old Vermont farm, and say, "Father, I have whaled," which involves all of sinning, and then eat fat veal all the rest of his days. |

"When that port is made, and I am safe anchored, and rich, and all that kind of thing, and can do as I please, I am goin' to ship a bosin-mate from the biggest seventy-four in Uncle Sam's blessed navy, and I'll give him a silver call; and his duty shall be to pipe all hands at eight bells (4 A.M.) in the morning, and to rap a handspike ag'in the mahogany (inlaid with whale ivory) door of my state-room, and rouse me out with, 'Starbo-a-r-d watch, a-h-o-y-oy!' Then I'll sing out, 'Watch be blowed!' and go to sleep again. What's the gain of bein' rich if you can't blow the starboard watch at eight bells?" Ben is about sixty-five, and has a chestful of old clothes yet. Fifty-two years he has spent at sea, with short intervals on shore. He never married, "because his mother was particular on the score of daughters-in-law." Ben is bruised, battered, and warped in body; seamed and wrinkled in brow, by fire, by ice, and shipwreck. The few fingers which the frosts of Labrador have left him are corrugated and doubled in, to fit close to the rope and the oar he has tugged at for half a century. During the war of 1812 be served in the Constitution, and labored faithfully and successfully in shooting some new ideas through Mr. John Bull's head. Growing tired of the humdrum and peaceful quiet of man-of-war life, he came whaling, as he expressed it, to "see life, to sweat the weeds from my figure-head, and to rub off the barnacles which deadened my headway; and, by the great hokey! I got in the right place in the Chelsea under old Captain Davis. I'll tell you green hands about that first whale I went on in the captain's boat." |

CHAPTER III.

"We was a-runnin' down the trades, in lat. 13 S., right about this very spot as it might be, and Lish Chipman there, he was at the mast-head, and raised whale. We ran down with the ship convenient, and lowered four boats. Captain Davis was real hungry and cantankerous for a whale, for he hadn't been in a fight for nearly six months; howsoever, the whale soon turned flukes and staid down, so that I thought he'd never come up ag'in. The captain was mounted on the gunwales, and Lishey was on the box; and we was a-lookin', each man over the blade of his own oar, to catch the first spout, when suddenly Lish uttered a cry that almost made one's marrow creep. 'Bill,' said Ben, addressing me, 'you're in his boat, and you'll hear him whisper that way some day, and you won't grow any more after hearin' it.' "Well, however, as I was sayin', Lisha, with a quiet yell, not much above a whisper, said, 'Look out for breakers, captain; take your oars, all of you, and don't speak for your lives.' He grabbed his iron, when, quick as a white squall, |

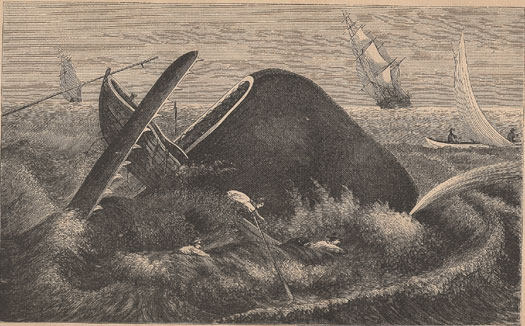

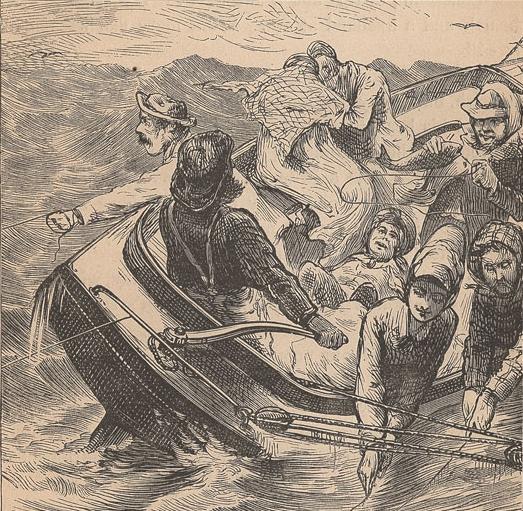

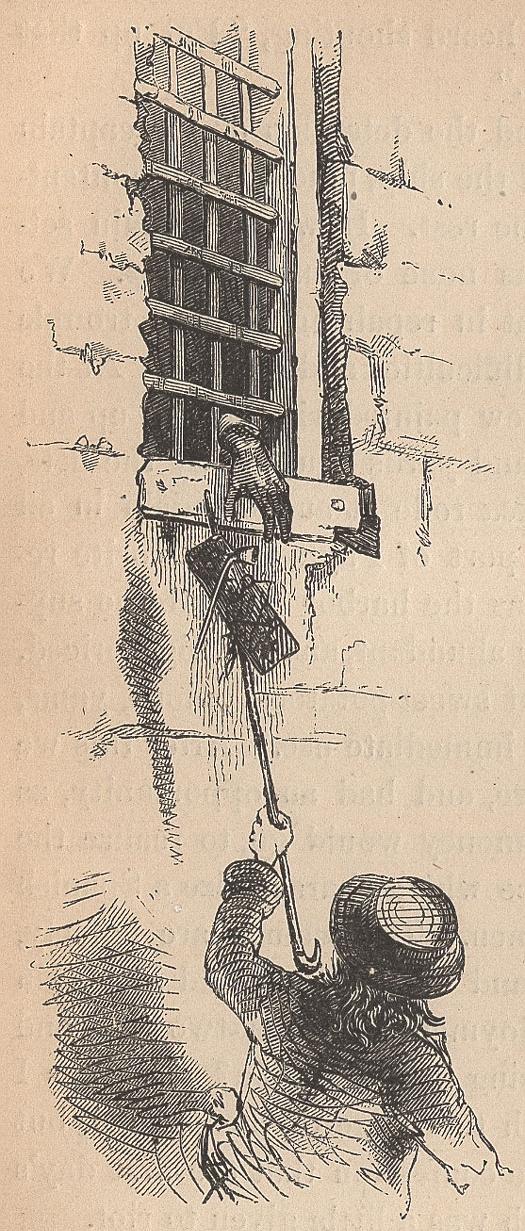

STRUCK ON A BREACH. |

there was the whale's head on a clean breach, not two iron's length from the head of the boat. We couldn't stir hand nor foot for the life of us. Up, up, not fast, the whale kept going. It seemed there was no end to him. The old man was gallied a little I think, but he let Lish have his own way. I don't think one of us breathed, or even winked, as we watched that awful black mass shootin' into the sky. I tell you, boys, you'll never really know how big a critter a whale is until you see him eclipsing the sun, as I did that blessed day. "And there stood that Chipman, his back to us, and at that minute, I guess, to all the world, with his iron and hand away back over his shoulder, a-waitin' and waitin' till the hump showed itself, and full fifty feet of black skin was in the air! It looked as if it hung right over our heads, when, holy Moses! Lisha clapped the iron in right up to the socket, and yelled out so they heard him aboard the ship, 'Starn for your lives! Starn all, I tell you!' At the same time he planted his second iron in the falling whale. Didn't we obey orders that time, I wonder! The boat had jumped its length, when the whale fell crashing right across our bows, nearly swamping the boat in the swell he raised, and more 'n half filling us with white water. "I never was at the Falls of Niagara, and, at my time of life, don't believe I'll ever go there for the express purpose of listenin' to splashin' water, as I have heard one uproar that showed what might be done. "The whale thought that blow between wind and water was foul, for he cut such infernal canticoes that we could not get on to him. He sounded out half the line, and then ran under water, and provoked us in that way till the old man got real mad, dashed down his hat, and let out one of his rip-stavin' swears. Old B––, you know, wouldn't swear to save his soul, let alone a whale! But our old man, Jeru- |

salem! how he could swear when there was honest life-and-death need of it! Well, while the old man was a-cussin', I heard cedar a-crackin', and when I looked around I was goin' up to the sky fast, with Captain Davis about half a boat's-length ahead of me. We parted company up there, for he kept on his course when I turned. I come down head first as in course, and went down into dark water like a bower anchor; I was kind of wire-drawn, and felt long as the mainmast. Bime-by I turned a sharp corner and glanced up, most as fast as I went down, and was gettin' party well into daylight ag'in, when all at once it was dark ag'in. I looked up, and there was the whale, like a-comet with a tail of seafire a-streamin' behind him, a-headin' right for me. Good Lord, how I sculled out of his course! He shot by me like a rocket, and when I came up on a half-breach, I was just dead-beat for breath. I spouted like a whale, and blowed out the surplush water, and got a good long breath. Oh, how good the blessed air comes to a famished, chokin' man! "Just then I heard something splash in the sea; I turned quick, and obsarved that the boat keg had just come down. 'Stand from under!' said I, and, I looked up, and believe it or not just as you please, but there was Captain Davis a-comin', end over end, makin' the tallest kind of headway to his natural level. This whirligig made me kind of sea-sick, and turned my stomick ag'in whalin'. I thought I'd carry out my old plans, and git to Vermont jist as quick as I could; so I got the sun well over my larboard shoulder, and struck out north, two points east, for New London. But the mate's boat overhauled me before I had swum far, and took me back to the ship, where the captain gave me a stiff can of grog, to qualify the salt I'd swallowed in my deep-sea soundings. "Now, boys, I never could make out exactly whether the captain went up very high, or I came up quicker than I |

thought for (I allowed that I was down about a half-hour), but, maybe, I only dreamed the dreams of the drowning, and saw sights which flit through men's heads in their last minutes. I asked Captain Davis once how long he'd been kiting that time. The old chap grinned, and said he hadn't looked at his watch, but he could now believe that the 'cow jumped over the moon' about the time when ' the little dog laughed to see the sport, and the dish ran away with the spoon.'" "How about Ben's yarn?" we inquired of Chipman, who sat quietly smoking his pipe on the end of the windlass. "Ben is about right in the main features of the case. I happened to look straight down from the head of the boat, when I saw the whale right under us, coming on a breach. He glimmered as bright a blue in the deep water as my sweetheart's bonnet. There was no time for thought, so I only acted on instinct and followed mother's last advice, never to let black skin go by the head of my boat without putting an iron in it, which the dear creature gave, illustrating it by throwing a fork at the black cat. But say, Ben, I was mortal feared the old man might order you to stare off before I could get my irons in. The whale didn't act so ugly as Ben thought; Ben was green then, you know, boys; but the durned critter did smash things when he hit us. But, then, nobody was hurt, although some were mightily skeart; and the old man himself owned that be got confused in his whirligig passage from the stern-sheets of the boat to the water." Such were part of the yarns called forth by the adventure of the day; and we young fellows retired to our virtuous straw, in the main pleased that we had passed the first ordeal without mishap, but sorry, of course, that we had hissed this first chance for oil. After this, long days passed as we sped southerly. Many |

false alarms were raised from the mast-head; ships were seen and passed; none spoken. We watched the little pilot-fish under the bows, and the great albatrosses as they sailed about the ship or floated gracefully on the water. About the Brazil Banks several of these great birds were taken by baiting a floated hook with fat pork. As the "Antient Mariner" hath it: "It ate the food it never had eat;" and, in consequence, it fell into the hands of those who had not the awful warning of the slayer of albatross before their eyes. We caught and killed them to obtain the long, hollow bones of the wings, for ornamental needle-cases for the "girl I left behind me." One grand old fellow, whose stretch of wing was guessed as twelve feet, and whose great, hooked beak seemed little in jured by his capture, we preserved from death to convert into a messenger. Writing the words "Chelsea,_ of N. L., Captain B––; all well; lat. 27° S., long. 36° W.," we secured the paper in oiled silk. This was waxed, varnished, rendered perfectly water-proof, and secured by a cord around the base of the. bird's neck. A red ribbon streamer was attached to attract attention. All being prepared, we headed our messenger by compass a true course for our " sweethearts and wives," and launched him on the wing with a loud hur ra. Forty-two months from this time we learned the conclusion of our venture. Five months after we had released the bird in lat. 27° S., it was shot from a pilot-boat off the harbor of New York, and our dispatch, with the manner of conveyance, made an item in the papers of that city. This was the first news our friends had received of the wild wanderers. Thus the albatross had come like a voice from the sea to many anxious hearts, bearing a welcome message five thousand miles, and, like the messenger from Marathon's bloody field, dying in delivering it. As I have anticipated in the case of the albatross, let me do the same with the little pilot-fish which leads our good ship on her way. From |

the neighborhood of the Cape Verd Islands, where it joined us, until we lost headway in the port of Callao, Peru, it accompanied us. Undaunted by the cold and the storms of the cape, it led the way into lat. 62° S., and during a fearful scud before a south-east gale, which drove us for forty hours at an average of. nearly fifteen miles an hour, we carried it into the shoal and perhaps too foul waters of a Peruvian harbor. The whole distance run by this little fish, allowing for traverses, was over 14,000 miles; time 122, days, or a daily average of 115 miles. In all these days, there was not a moment when the ship had such headway on her that our pilot might not be seen distinctly in front of the cut-water. By day, we could see it near the surface at our rising and falling bow; by night, in the phosphorescent seas it shot along, a gleaming flame, just in advance of the scintillations caused by the spurt of the cut-water. Our little companion obtained the interest of the crew, and word that it was still with us was passed. from watch to watch. It finally entered into the superstitions of our ship, and its leaving us would have caused concern to many minds on board. Among nien and officers there was no doubt that it was the same fish that joined us on the coast of Africa, and followed us south 77 degrees of latitude, thence' north 50 degrees, making west 60 equatorial degrees, boarding itself meanwhile, without a watch below for sleep or rest. Let any boy or girl turn to the map of the world, and trace this long track of a fish not over twelve inches long, and think how wonderful are God's ways even with the smallest creatures-ways so wonderful that they are past finding out by grown men, even professors in natural history. In the days that gradually grew longer as we approached the cape, the time of the watch on deck (or half the crew in turns of four hours each) was employed in pulling old rigging into yarn, knotting the yarn and winding it into con- |

venient balls, or, by a simple wheel and axle, spinning it into rope-yarn for rigging again. The finer and evener yarn was neatly woven into mats to prevent the yards from chafing. The old sailors would neatly point ends of rigging or work the various knots of the "rose," and "double rose," the "wall," and "wall and crown," each having a special place and service. To "roan-rope," "bucket-rope," " stoppers," etc., etc., are the accomplishments of the able seaman, next in order to reefing and steering. Inability to place the appropriate splice or knot in the appropriate place is deemed lubberly. Endless were the lessons patiently given and received in this intricate and important part of a sailor's education. Long were the discussions, and countless the authorities quoted to establish diverse views as to the placing of some knot, splice, point, or seizing. Things were simplified to me, however, when I learned that in all the tangle of. taut, strained, or swinging lines, there were only three ropes in the ship-viz., man-rope, monkey-rope, and bucket-rope, with a rope's end to every piece of standing or running rigging. The first piece of rigging my poor brain, located was the clew-garnet; its mineralogical association fixed that. From this little point I soon got over the lubberly habit of asking some one to "cast off" or "make fast" this or that rope, and began to chatter in the best sealingo about "swifters," "fore" and "back stays," "braces," "halyards," "falls," "purchases," "jewel-blocks," "ear-rings," "chains," " forefoot" and " taffrails," " binnacles" and " lockers," and to respond promptly to " bowse, taut, and belay all," and to "cast a bowline" or "double hitch." The mystery of the short and long splice, the "grummit" and " thole mat," the "thrum" and the "point," afforded play to the fingers which had practiced with the trout-flies and lighter tackle of the gentle art taught by Izaak Walton, of most worshipful memory. The useful art of washing and mend- |

ing was not neglected, and we collected our rents as faithfully as did the closest landlord of the dry land. A sailor should be able to direct the building of his ship from royal-truck to keelson, and rig her with his own hand from a rope-yarn to the "hawser bend." But he must also know the altitude of the sun which will cast a true forked shadow on a piece of duck, as pattern for a pair of trowsers; he must work the American eagle and a true-lover's knot in blue yarn, to quilt his flannel shirt against the cold of the cape; he must plait the split palm-leaf into pointed sennit for his tarpaulin hat; he must never want protection for his feet against cutting rocks, when his club can secure him a seal or sea-lion; he must stand by a shipmate in trouble; jump at the order of his officer, never " sodger," of all things, never question about God and his ways on deep water, and never flinch from the tallest kind of a row when the honor and good name of his mother or country are called in question. Such was the teaching on the forehatch of the Chelsea, as we scudded past the mouth of the La Plata, and made preparation to meet the old Storm King who.has his home in the Antarctic. As the days lengthened and the nights grew less dark, the more exact history of the business we were engaged in occupied many of the idle hours of the night-watch, our ship bowling along, without labor or care other than that of the man at the helm and the lookout on the bows. In this lore my special crony, Posey, delighted. To question him on the history of Nantucket, New Bedford, Sag Harbor, or New London, and of the famous captains who had fished in these beautiful towns, was to open the flood-gates of his knowledge. Often, on the quarter-deck and on the forecastle, he would talk to delighted audiences about the antiquity of our craft, and the high honor in which it had been held by great princes and powerful nations of the earth. Posey was a |

great favorite with officers and men. Never in the way, his hand and voice were always present when they were needed. He had auburn hair, and blue eyes, set in a broad, sanguine face (hence unaccountably, it was said, the ship-name of Posey), wearing an expression of sadness. Posey was a scholarly man; his hands were delicate, and he had a stoop which neatly fitted him to the low ceiling of our forecastle. He was not at all the beauty of the crew, and he had not come to sea to escape the "fool-catcher." He pulled the bow-oar in Mr. F -'s larboard quarter-boat, and so was in direct line of promotion. His heart was in his work, and he used all his energy to win his way to the harpooner's place. No boat was lowered to practice on black-fish in which he was not a volunteer, and he was always on hand to aid in coiling line in the boat-tubs and in mounting and grinding harpoons and. lances. In fact he was a ready hand for the hundred little details which go to complete the gear of a whale-boat. In a night-watch he confided to his companions the inspiration which sustained him, cheery and unwearied, in the hard, uncongenial life in which he was immersed. I was young and heart-whole, with my love in the wild, wandering life before me, and was amused, rather than interested, in the story which told of a young scholar from Vermont, who found home and occupation as master of a school in Nantucket. The old, old story it was – old as the Garden of Eden. A man met the woman he loved, and found, too late, that he could only win the daughter of a long line of the nobles of the island – the whaling-captains – by winning his knighthood at the head of the whale-boat. A true daughter of the land, the girl desired the security of a home founded on the traditional harvest-field of her ancestors. How could it be helped? She had been taught to refuse to dance with one who had not been fast to a whale, and never to accept a |

hand which had not planted a harpoon. So, in due course, when he avowed his love, Katie, with a smile of encouragement, replied, "Dear Garvin" – that was his proper name – "sing that song to me after you have struck a sperm-whale, and it will sound more real." How could the bonnie lassie do otherwise? In her home she had been severely trained.

NANTUCKET SCHOOLING.One day she saw her good mother throw a loving arm around her father, and say, "Jack, dear, one of us must go a-whaling, and I can't." "Why, what's up now, Dolly?" the briny old man asks. "There's low tide in the bread-kit, and another mouth is coming." |

The dear old fellow stows his kit, kisses Dolly and the little ones, and, leaving a kiss for the coming stranger, goes to sea for a four years' voyage. Katie, with a daughter's love, looks into the mother's eyes, and says, "We're lonesome, now that father's gone." "Lonesome, dear? not a bit of it. We have a clean hearth and a husband at sea. What more can woman desire?" In such a severe atmosphere no sehool'boy love could flourish, but Posey had heroic stuff in him. The idea never entered his head to slip his cables and drift out of action. He recalled the servitude of Jacob for the woman be loved, and he said, "It is a little thing to serve one voyage for Kate; and if I am only lucky enough to have Mr. F put me on a whale, I won't miss, be right sure." Such was Posey, the banished school-master. The starboard watch was on deck one day, when Posey gave us the following "key to Nantucket's success in the whale-fishery:" "From the first, our people clubbed their means to build or buy the vessel, and many of the necessary branches of labor were conducted by those immediately interested in the voyage. The young men of the island, with few exceptions, were brought up to some trade necessary to the business. The rope-maker, the cooper, the blacksmith, in brief, the workmen, were either the owners of the vessels, or were connected with the families of the capitalists. While the ship and part of her owners were at sea, the remainder in interest were busily employed at home preparing an outfit for the succeeding voyage. The cooper, while employed in making the casks, took good care that they were of sound and seasoned wood, lest they might leak his oil in the long voyage; the blacksmith forged the choicest iron in the |

LIGHT-HOUSE, SANKATY HEAD.shank of the harpoon, which he knew, perhaps from actual experience, would be put to the severest test in wrenching and twisting, as the whale, in which he had a one-hundredth interest, was secured; the rope-maker faithfully tested each yarn of the tow-line, to make certain that it would carry two hundred pounds' strain, for he knew that one weak inch in his work might lose to him his share in a fighting monster; the very women and girls who made the clothing remembered in their toil that father, brother, or one yet dearer to them, might wear the garment, and extra stitches were lovingly thrown in to save the loss of button and prevent the ripping of a seam. Thus the profits of the labor were enjoyed by those interested in the fishery, and voyages were advantageous even when the price of oil was barely sufficient to pay the outfit, estimating the labor as part of it. |

"How could the British capitalist, who required a net profit, compete with this industrious hive of co-operationists? His Government aided him by a bounty equal to $10 per ton on the burden of his ship, protected him by excessive duties on American oil, and granted immunities to his seamen. All was in vain, and He was compelled to yield the field. Listen also to the words in praise of our whaler, penned by a hand that wielded harpoon and lance as successfully as the pen. Obed Macy, of Nantucket, tells us: 'His youth and strength, his manhood and experience, are devoted to a life of great labor and much peril. His boyhood anticipates such a life, and aspires after its highest responsibilities, while his age delights in recounting its incidents. For deeds of true valor, done without brutal excitement, but in the honest and lawful pursuit of a means of livelihood, we may safely point to the life of the whaleman, and challenge the world to produce a parallel. The widow and orphan mourn not over his success; oppression and tyranny follow not in his paths; his wife and children reap the reward of his toils and danger, and his prosperity is his country's honor.'" "Every word of that is true," said the captain, who was listening to Posey, while his thoughts were doubtless soaring beyond the snow-capped Cordilleras, to a quiet home, and wife, children, and friends, near the distant hills of New England. |

CHAPTER IV.

The first white who settled the island of Nantucket was Thomas 14 lacy, a brave, righteous man, a hater of tyranny, a contemner of religious bigotry, a hero in every particular fibre of his being, right worthy of founding a community so virtuous, hardy, and adventurous, whose members by their lives have made their desert island a monument of human enterprise more enduring than bronze or marble. "Having my hand in," said the school-master,"I would like to reach down into the ages and show you how ancient is our craft, and how honorable it was held above all other commercial enterprises by the rulers of the Old World, and how desirable was the business to the governments of great nations. I would like to show you how princely bounties to the merchant, and privileged exemption to the mariners, have failed in hiring England's sea-dogs to hunt the grandest of ocean's game. Thus you may realize what the American has done, unaided save by his natural attributes, in winning unexampled success in this grand and hazardous vocation. "That our craft excited a lively interest in the English at |

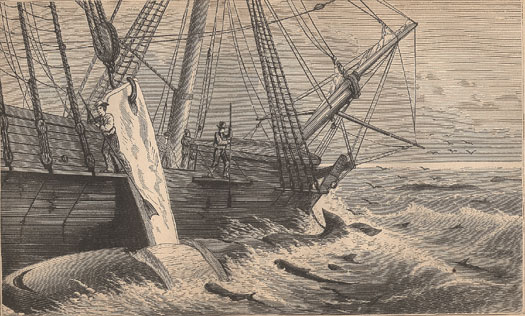

a very early period in their commercial history, is shown by Alfred's account of Ohther's adventures; and we find in Hakluyt's voyages that, in 1598, an honest merchant requests, in a letter to a friend of his, 'to be advised and directed in the course of killing a whale.' The answer conveyed the information that ' all the necessary officers were to be had from Biscay, whose people had pursued the hazardous business since A.D. 1390.' "The English went on, from 1598, unrivaled with their whale-fishery in Greenland, until 1612, when the Dutch first. resorted thither; whereupon the English-Russia Company's ships seized the oil, fishing-tackle, etc., of the Dutch, and obliged them to return home, threatening that, if they were ever found in those seas thereafter, prizes would be made of their ships and cargoes. The English whalers claimed that their master, the King of Great Britain, had the sole right of the fishery, by virtue of the first discovery thereof. The natural result of this peculiarly English proceeding was, that in 1613, while the English sent thirteen ships, the Dutch sent eighteen ships, four of which were men-of-war of the States, and they fished in spite of the English companies' pretensions. "In 1617 the quarrels ran very high between the English and the Dutch. The former persisted in seizing one part of the oil; and this is the first time mention is made that the fins or whalebone were taken home with the blubber, although probably before this date it came into use for women's stays, etc., through the Biscay fishermen. The whales, never having been disturbed, resorted to the bays and the seas near the shores, and their blubber was easily landed, and the oil extracted in boilers which were left standing from year to year. But after the violation of their sanctuary the whales became less frequent in the bays, and commonest among the ice farther from the land. The ships follow- |

ed them thither, and the blubber could no longer be landed, but had to be cut from the floating whale in .small pieces, and brought home in casks for boiling. The new method of fishing was often found dangerous to man, and perilous to shipping. So discouraged were the English adventurers, that they soon afterward relinquished the fishery, until the time of Charles II. In 1618, with respect to the whale-fishing of Holland, De Witte quotes Sievan Van Aitzma, who says that the whale-fishery to the northward employs about 12,000 men at sea' Anderson, in his 'Annals of Commerce,' treats this as an exaggeration. "In 1634 'The Dutch Greenland Company' made an experiment of the possibility of human beings living through a whole winter at Spitzbergen, till then believed to be impossible. They left seven of their sailors to winter there, one of whom kept a diary from the 11th day of September to the 26th of February following. The men were then down with the scurvy, and their limbs were benumbed with the cold, so that they could in no way help themselves. They were found dead in the house they had built for themselves, on the return of the ships in 1635. In 1670, Sir Joseph Child, in 'Discourses on Trade,' informs us that in 'the Greenland whale-fishery the Dutch and Hamburgers have annually four or five hundred ships, and the English only one ship last year, and none in the former one.' In an account of the Dutch whale-fishery for forty-six years ending in 1721, we are informed that the 5886 voyages made had secured 32,906 whales, valued at £16,000,000, a clear gain out of the sea, mostly by the labor of the people. "In 1740 England made a determined effort to establish the business in her dominions, To this end she granted au additional bounty to those formerly established; making in all thirty shillings per ton for each voyage on the ships employed; and to induce her mariners to engage in the busi- |

ness it was enacted 'that no harpooner, line-manager, boatsteerer, or seaman in that service should be impressed into the naval service.' Such immunity from the odious tyranny of the press-gang, we should think, would have flooded the whaling service with seamen; but no! the perils of this fishery were more terrible to the English imagination than forced service under the thunder of great guns. Eight years later, the bounty was increased to £2 per ton on the ships employed, and the foreigner was invited to do for England that which British seamen failed to do. The following was enacted 'Foreign Protestants who shall serve three years on board British whale-fishery ships, andshall take the usual qualification oaths, shall be deemed natural born subjects of Great Britain to all intents and purposes, as far as other foreign Protestants can so be.' Stich is the evidence, that the' jolly British sea-dogs,' the 'hearts of oak,' had no hankering for the whale fight, and that Britannia could not rule that wave at least. Now the hand of the American whaleman is first felt in the markets of the world. Nantucket, in the year 1761, employed ten vessels of one hundred tons each; in 1762, fifteen vessels; in 1763, above eighty vessels; 'whereupon,' says M'Pherson's Annals, 'the increasee of the quantity of whalebone imported from New England to Britain reduced the price of whalebone from £500 to £350 per ton.' From these annals we also learn that in the thirtynine years to 1788 the whaling voyages made from Britain numbered 2874, and the sum expended from the treasury in bounties amounted to £1,687,902. "The British Government continued to manifest the liveliest solicitude in the development of the fishery, and in 1795 the following additional bounties were granted: 'To the vessel proceeding to the Pacific Ocean, continuing four months upon the fishing-ground, and, after being sixteen months out, having the greatest quantity of clear sperm-oil, |

£600; to each of the seven having the next greatest quantity, £500.' And it was further provided by the act of June 22, 1795, 'that foreigners, not exceeding forty in number, who had previously been employed in the occupation of fishing for whales, and were owners of vessels, should be permitted to come to Milford Haven, in Pembrokeshire, with their families and vessels, not exceeding twenty in number, each vessel being manned by at least twelve seamen accustomed to the fishery. They were allowed to import their goods, furniture, and stock, duty free, on giving security for their residence at least three years in Great Britain. They were then entitled to the premiums granted to British fishermen, and in general to all the rights and privileges of natural-born subjects.' "Opposed to this picture, I quote Captain Wilkes: 'The American whaling-fleet now (in 1840) counts six hundred and seventy-five vessels, the greater part of which are ships of four hundred tons burden, amounting in all to two hundred thousand tons. The majority of these vessels cruise in the Pacific Ocean; between sixteen and seventeen thousand of our countrymen are required to man them. The value of the fleet is estimated at not less than twenty-five millions of dollars, yielding an annual return of five millions, extracted from the ocean by hard toil, exposure, and danger.' This wonderful success of our whalemen has been achieved in the face of an almost complete destruction of the ships in the two wars with Great Britain, and entirely unaided by any particular encouragement by Government in the form of. privileges or pecuniary aid." Having transgressed the directions of my good angel, and remembering that to become statistical is felonious, I beg your pardon, good reader, and promise to abstain therefrom most religiously hereafter. Posey has had his scholarly say, and we will clap a stopper on his tendency to figures. |

Approaching the cape, the inexperienced were somewhat daunted by the preparations our prudent captain made to meet the boisterous nature of this passage from the eastward. All the spars above the topmasts were sent down, the anchors taken from. the bows, the stocks removed, and the ponderous iron securely lashed to the deck ring-bolts forward. Our boats were taken from the cranes and secured on the over-deck spars, spare topmast,-and yards; scuttlebutts were double-lashed; and the cook's house was strengthened by the proper disposition of the lighter spars. Merchantmen and hide-droghers may smile at such precautions on the part of whaling captains, especially considering the strength of their crews; but it must be kept in mind that we came to get oil, not to risk the ship in boastful display of fancy sailing. We frequent seas where repair of damage is difficult or impossible. Our resources are within ourselves, and we husband our strength until we arrive on the actual field of operations. A man-of-war's-man may anchor in the rollers in the bars of well-known harbors, and be held to her surging cables, with imminent risk to the ship and death to part of her crew, although, confessedly, to retrieve the error, they have but to slip their cables and drift into the calm harbor in full sight. Such was the case of the Vincennes on the bar of San Francisco; and another such lubberly feat sent the gallant Peacock to the bottom on the bar of Columbia River. No captain of a whale-ship would again sail in command who was guilty of such manifest ignorance of seamanship. The officers in this service are held to such strict accountability for the safe return of the ship, after the longest voyages, and the greatest actual sea-service, that their vigilance is incessant and unexampled. Loss by fire, or the powerful drift of currents during calm, or by the crushing of floating ice, may be shown to be unavoidable cause of wreck; but sel- |

dom may a whaling captain plead stress of weather or error in reckoning, ignorance. of entrance to harbors, or the dangers of bars, as a valid defense for the loss of his ship. I was continually impressed by the unceasing vigilance of Captain B––, to keep the exact run of the ship. The log was as regularly kept as though we ran by dead-reckoning; and we were running almost in mid-ocean, with land hundreds of miles from our known position. Yet every clear night, or whenever :a break in the clouds admitted the observation, the captain would glide silently on deck, sextant in hand, and, taking his seat at the head of a quarter-boat, would abide his time to get his meridian by the passage of some star of the many brilliant constellations in the southern heavens. Not once, but perhaps several times in. a night, he sat star-gazing and full of anxious care, while the thoughtless youngsters were listening to the song and the yarn, thinking of the good time the "old roan" had, and wondering why captains grew gray-haired so early. The highest testimony to the seamanship of our whalemen is that the rate of insurance on the American is just one-half of that on the British vessels engaged in the service. In illustration of this point, Macy informs us that the whole number of Nantucket vessels lost, exclusive of captures in war, since the settlement of the island to 1835, is 168; viz., 78 sloops, 31 schooners, 18 brigs, and 41 ships. Yet for many years Nantucket had 150 ships at sea, on voyages of great length, and in distant, dangerous, and unexplored seas, unaided by correct charts or sailing directions. The loss of lives by wreck in this time was but 414. Unquestionably the seamanship of the American whaling captain is of the highest order in every respect, and many of the most successful and adventurous commanders of packet and clipper ships graduate in this school. The seamen educated in whaling have no superiors in the substantial el- |

ements of the sailor, although they may lack the jaunty tie of the cravat, the saucy cock of the new tarpaulin of other sailors, and may make less parade of their peculiarities on shore. To be sure, they are clumsy and rough as the walrus on dry land, but they only need the wash of deep blue water and the excitement of the chase to bring the true elements of their character to the surface. No one can witness the change which attends actual service in the boats, without astonishment. The dull, sluggish, and sleepy become full of animation, dash, and endurance. Fortunately our careful preparations were needless. We made what was considered a good passage going west, head-winds and the set of a head-current forcing us into 62° S., when a cape gale from the south-east sent us scudding "norrard" at railroad speed. The log reported fifteen miles an hour, continued with a nearly equal rate for forty hours, and left us fairly round the cape with the broad Pacific before us. Many were the stories of prolonged storm and terrible suffering endured in the passage of the cape. At certain seasons the great south-west storms buffet the outward-bound ship for weeks, and she drifts before it, laying to, and becoming unmanageable from the accumulation of ice on her bull and rigging. We youngsters had the benefit of a relation of these experiences, and consoled ourselves with the thought that it would be at least three years before we would again encounter the stormy cape. The following gorgeous and mythical story by Hinton will give an idea of the "lay" and fibre of a Cape Horn yarn: "We had made a good voyage. The Chelsea was full of oil, and we were homeward-bound. We had mounted a new suit of sails in Talcahuana – stay-sails, double-stitched – and the old beauty was in perfect trim, except that her copper was rolled up, and the grass and barnacles fouled |

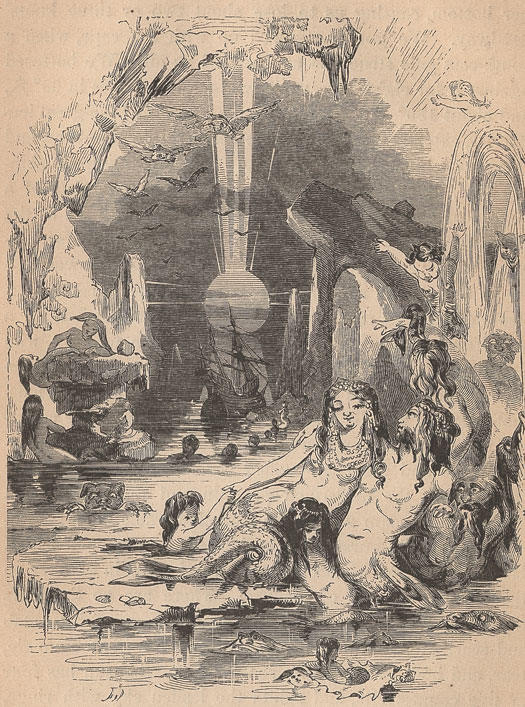

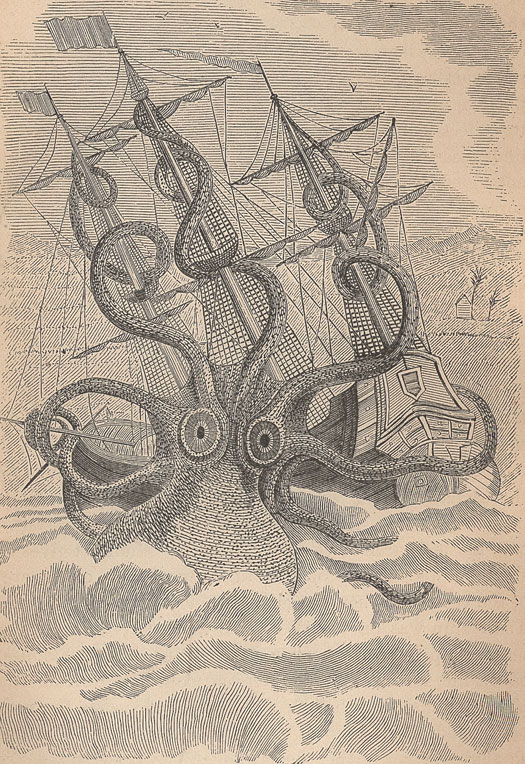

her bottom, causing us to lose about two or three knots' headway. We got pretty well up with the cape, when a south-east gale struck us and headed us off. We battered against it for eight days, when we found ourselves in 68° S., and about 130° W. Here we came in sight of the great icebarrier, extending far as the eye could reach, plumb up and down, two hundred feet or more. This was the great shining wall, beyond which, we are told by the scientists of a couple of hundred years ago, lies the great open sea of the Antarctic, where dwell nations of mermen and maids; krakens, with ' amethyst and golden antenn e, of power and scope to entangle and draw down great ships; and sea-serpents of hideous mien, and fathoms in length;' where, in a wondrous palace of ice, dwells the southern ice-king, who drives the frost-fiends to labor on icebergs, and store treasures of the hail and snow; where the marmicle and marmate gambol in fields of the giant kelp, and herd the countless shoals of mackerel and herring; where the ivory-toothed walrus and the shag-marred sea-lion keep guard over the nests of the uniformed penguin and the albatross: a sea, in whose calm waters the wounded whale finds sanctuary against the pursuit of the hunters of the open ocean. Here the worried whales find peace, and grow in blubber on the crimson carpets of medusa. There are no threshers there to club the old backs; no sword or saw fish to stab and scarify; no Nimrods to harpoon and lance, to mangle, tear, and boil. Above this sea a six months' sun has four or five counterfeits, and paints the leaden sky with rings, and crosses, and crescents of colored fires; and the six months' night is illumined by the coruscations of the aurora borealis. "In the centre of this sea is a circular marble throne, whose base has three hundred and sixty divisions, from which meridian lines run out and span the great world; |

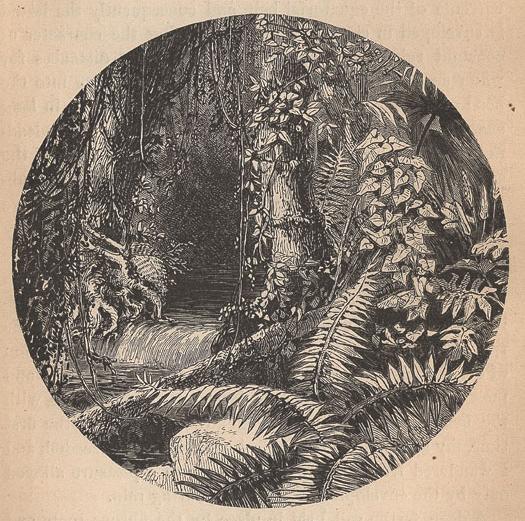

THE SEA BEYOND THE SHINING WALL.and from its centre rises a pole of electric light reaching upward into the heavens to the constellation of the Southern Cross. On this throne sits Mother Carey, the fashioner and maker of millions upon millions of new creations of more varied shapes, colors, qualities, and functions than |

any but little children ever dreamed of. She sits quite still with her chin upon her hand, looking down into the sea with two great, grand blue eyes, as blue as the sea itself. Her hair is as white as the snow, for she is very, very oldin fact, as old as any thing which you are likely to come across, except the difference between right and wrong. "Such is the sea beyond the ice-barrier, as our fathers believed it to exist, even after Columbus taught the world how to make an egg stand on its end. "To come back to my story, however," Hinton continued: "As we stood by the ice-wall, the weather thickened, and a heavy snow shut out the ice. We were standing along under close-reefed maintop-sail, reefed courses, and try-sail. The spray of the sea went right to ice as it touched the deck and rigging. We were heading aslant the wall; it was still light enough to see that we were among floating ice, and we could catch glimpses of the cloud-like outlines of great bergs, which it would be destruction to touch. The captain stood under the lee of the mainmast, his clothes covered with ice, giving orders to the men at the wheel. The wheel was double manned, and the mate stood by to see that the helm was well served. The wind was* piping its strongest, and the combing seas were such as are only to be seen off Cape Horn. The drift and ice islands came on us thicker and faster. Once we passed to the windward of a great iceberg, higher than the mast-heads, and we held our breath as we listened to the thunder of the great waves, which one moment tossed our little craft, and the next burst with awful force against the ice under our lee. "We suffered very much from the cold; our clothes were stiff with ice. We were dashing blindly on, but with good steerage-way, and the ship answered quickly to her helm, although she ran deep by the head on account of the accumulated ice on her bows and head-hamper. Now the cry |

came, 'Ice ahead!' Then, on the weather or on the lee bow, the pounding and grinding of the rocking bergs, the roar of the breakers, and the awful tone of the wind as it cut through the strained rigging, almost drowned the hoarse orders of the captain as they came through his trumpet. So we dashed through the darkness and blinding snow, every eye awake to watch for ice; every ear expecting the crack of doom. |

CHAPTER V.

"At times the ship was almost on her beam-ends, and the sea was making clean breaches over the bows and waist. Great surges would leap in the air and drop on her deck, making our timbers, to the very keelson, twist and tremble. The poor ship groaned and complained like a sick man. Masses of ice, too, swept across with the water and carried away the rail and planking of the bulwarks. – Suddenly the overborne ship righted and rolled easily on an even keel. So close were we tinder the lee of a great iceberg that we rode as if we were in a harbor; but the roar of the storm was all around and above our beads. We drew slowly ahead,'and came out into the storm again, but as far as we could see there was open water, and we felt as though we were saved. Toward morning it cleared away, and in the lull of the storm we could hear the puff of whales as they were making south for the icy wall. Now and then a gleaming light would play along the front of the great wall, and bring every crag and peak into radiant relief against the jet-black sky. Old Captain Davis said it was a beacon-light to guide every creature that sought its shelter. |

"The next day, with wind north-west, we stood for the cape, and saw no more of the ice-wall; but the following night we saw a bow of shooting lights, reaching a great distance across the sky, shooting and waving tender colors, now opening and shutting like a fan, now lighted up with crimson fires. Ob, man alive! you should see this glory of the southern sky as we saw it that night, and you would dream, with Jobn, that you were looking into the gates of the New Jerusalem! I heard the old man say that these lights only reflected the brilliancy of the crystal palaces, and the colors of the bright waters of=the sea beyond the shining wall." As Hinton concluded, some one recited from the "Antient Mariner:"

This started a discussion among the savants about the curious mistake the poet had made in attaching this superstition of a protective guidance to the great albatross, instead of to the little floating, skimming "Mother Carey's chicken." "Why, you see," said Coffin, "the albatross carries such a spread of sail that he's busy enough takin' care of himself in a gale, and you find him huggin' close to the ship in good weather only, and then he's lookin' for grub. But the worse |

the gale the more chippy is this little black butterfly of a Mother Carey, and no man's heart feels lost while he sees the little specks finding a safe lee from the hurricane right under the comb of the breaking rollers. You young 'uns may laugh at me for soft, but I tell you when you get as old as me you'll know a darned sightless than you do now. In the worst gale I ever was in off Cape Horn, where the gales are the worst of any place in this world, a great sea ran from under the keel, and let the ship down so fast that you could hardly keep with her, and you'd grab the rigging to keep along. And when the ship struck the bottom of the trough with a chuck that made her tremble as if she had an ague fit, and the on-corning sea, high as the mainyard, was a-rollin' down us with a hissin' comb, and the dark wall of water was so straight up that I thought it would breach thirty feet over us-in the very worst of this a whole flock of Mother Carey's chickens came down, hovering close under the breaking white-cap, safe harbored from the blast. I thought of the promise that as the sparrows are cared for so would we be; and whenever I saw these little bunches of black feathers playin' safe in the hollow of the sea, I never could get up much of a scare as to what would happen to me." Our men all felt that bad fortune would attend the killing of one of these little birds, and I found something of the same feeling among the sailors of other ships. Among the yarns of the cape, a favorite one with our crew was "the dismasting of the Ironsides under the lucky Captain Folger." "He was always lucky," said Harry, "and never more lucky than the night off Cape Horn when he lost every spar to the stumps, ten feet above deck. I'll tell you how it was. Ours was the luckiest ship that sailed from Nantucket, and the captain was the luckiest man that ever trod shoe-leather. He had made five voyages to the Pacific; come home |

full, 'Chock-a-block;' never over two years out; and he never lost man, boat, or spar. There was not a boat-steerer but was glad to go on a one-hundredth 'lay,' and he'd get rich at that. I went with Folger oil his sixth voyage, and steered Mr. Starbuck, the first mate. In twenty-one months we were off the cape, homeward-bound, try-works overboard, and every thing that would hold oil-case-bottles, captain's boots, and medicine-chest-was filled with head matter. We hadn't a man hurt, not even the skin scraped off a man's shin in the rigging, and that, you know, is extraordinary. Nor had we a plank started in a boat, or a spar sprung. The whales would seem to spout thick blood if they were struck forrard of the hump, and the main course would seem to furl itself in a gale. Something was wrong about the ship, and our good luck frightened us. Well, we were off the cape; the night was as black as my hair, a stiffish breeze was over the quarter, and we headed free on a course, every sail drawing. "We were makin' a splendid run, when Mr. Starbuck ordered top-gallant sails in; but before we started halyards or sheets, Captain Folger put his head tip the companionway and sung out, 'Stand fast there; belay all, and let her run. Excuse me, Mr. Starbuck, but I've the cards in my hand to-night, and mean to play the game out. Please crack on her as long as she'll carry. So we forged on for half an hour, when the wind hauled abeam, and we braced the yards forrard. This brought us down, scuppers under. The captain was on the weather quarter-deck holding on to the mizzen rigging; Mr. Starbuck was opposite to him, leaning against the companion-way. Two men were at the helm. The old ship was brought to her best bearings for a run, and was plowing a wake of foaming light through the dark waves. The whistle of the wind was changing to a. hoarse growl that meant business. Every thing was terribly strain- |