|

Henry T. Cheever, 1814-1897. |

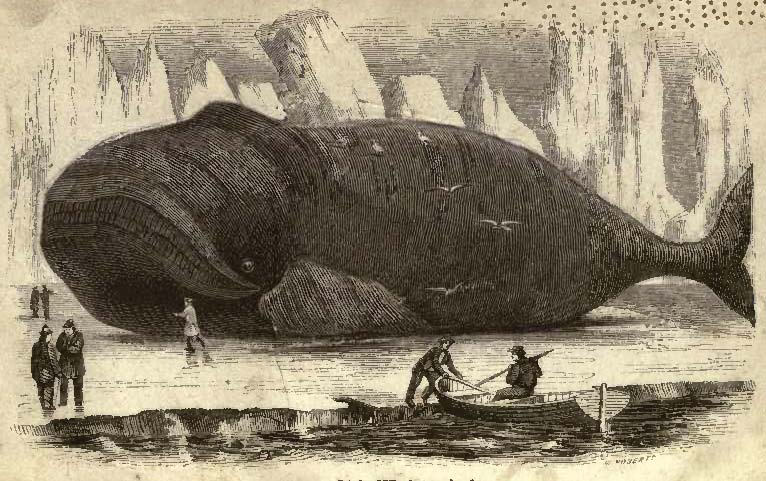

A Polar Right Whale on the Ice.

A Polar Right Whale on the Ice.

|

|

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand

eight hundred and forty-nine, by HARPER & BROTHERS, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Southern District of New York. |

And if it be true, what the philosophic Latin poet Lucretius touches so beautifully,

It is a view of delight to stand or walk upon the shore side, and to see a ship tossed upon the sea; or to be in a fortified tower, and to see two battles join upon a plain; or it is sweet, from a post of safety, to review the labors of other men beyond the seas – if there be truth in this, the writer may hope his book will not be barren of interest to many, who, having never experienced the reality of the life which is here delineated, may now behold it safely from afar off. Hoping also that there are moral hints and lessons herewith interwoven, that will catch the eye and touch the heart of the casual reader, like sober threads of green in tapestry of gold, this book is honestly commended to the purchase and perusal of all classes, by the AUTHOR.

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS.CHAPTER I.INTRODUCTION.

CHAPTER II.A SOUTH SEA CORAL ISLAND.

CHAPTER III.RAISING AND CUTTING-IN WHALES.

|

CHAPTER IV.NEW ZEALAND CRUISING GROUND.

CHAPTER V.THE WHALE'S PHYSIOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY.

CHAPTER VI.DIFFERENT CRUISING GROUNDS AND NORTHWEST WHALING.A Whaleman's Autobiography in Rhyme – Different Kinds of Whale in the Nomenclature of Whalers – Razor-back and Fin-back described – Resorts of the Right Whale – Great Harvest Field of the Northwest – Vast Havoc of Game there – Prowess and Sagacity of the Kamtschatka Whale – Beginning and Progress of Northwest Whaling – New Arctic Cruising-ground – Probable Duration of this Whaling – Maury's Attempt to reduce the Whale's Times and Seasons to a System – Fact and Speculation – A Problem for Posterity 95 |

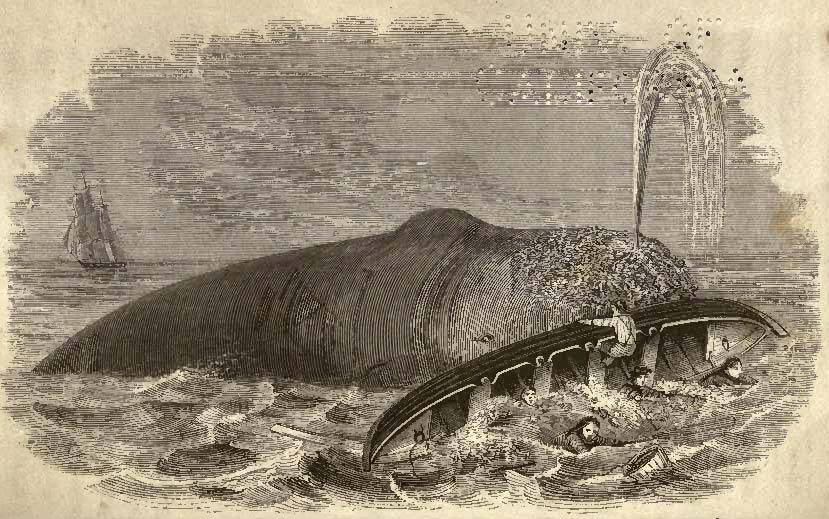

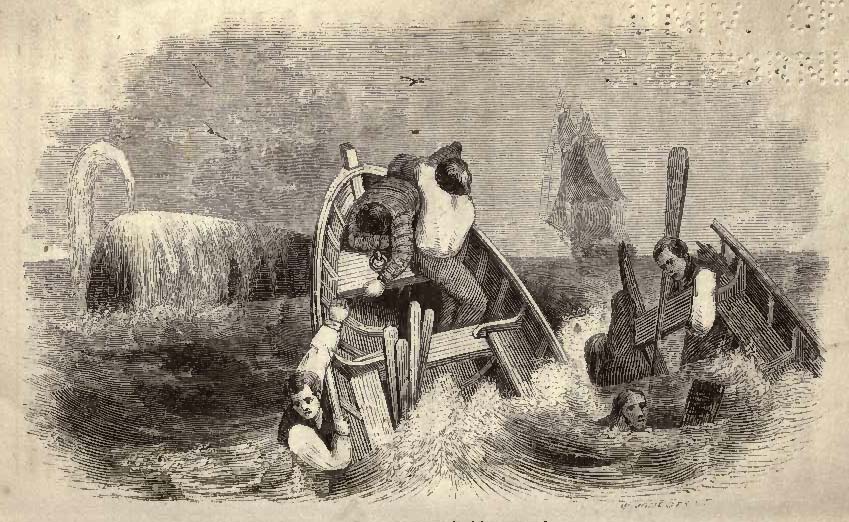

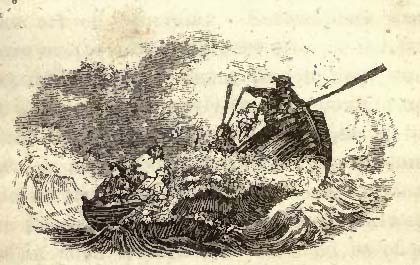

CHAPTER VII.THE WHALE'S BIOGRAPHY AND INCIDENTS IN THE CAPTURE.Amicable Temper of the Right Whale – Wisdom of the Creator – Whale's maternal Affection and Boldness in Defense of its Young – A Sperm Whale feeding – A Sperm Whale dying – A Sperm Whale Sick and wanting Physic – Ambergris – Its Origin and Uses – Deformities and Wars of Bull Whales – Probable Age of the Dam and Size of the Whale Calf – The Whale's Enemies – Terrific Combats with Killers, Thrashers, Sword Fish, and Sea Serpent – Doubtful Morality of the Whale Fishery – The Sabbath a Whaleman's Right 110CHAPTER VIII.ATLANTIC OCEAN MAMMOTHS AND MONSTERS.A Day and Night off Cape Horn – Capture of a Calf and Escape of a Cow – Harpooning of a Sun-fish – Metamorphosis into a Chowder – Sinking one Thousand Dollars in a Right Whale – Making Twenty-five Hundred in a Sperm – Lodging Harpoons in a Third – Whales Reading Lectures to Men 128CHAPTER IX.EPISODES IN THE FORTUNES OF WHALEMEN.Stirring Adventure amid a Gam of Whales – Captain Overboard with a tangled Tow-line – Sensations while being drawn down with the Sounding Whale – Providential Rescue – Boat-race with a Team of Whales – A Monster in his Flurry pitching downward and Dying without Rising – One Whale Falling bodily upon a Boat fast to another – Limbs broken and Lives lost – Reflections of the Rescued – The Heart under the Pea Jacket. 136 |

CHAPTER X.CONQUEST AND DISPOSAL OF A BULL WHALE.Off the Rio de la Plata – Gauge and Dimensions of a conquered Sperm Whale – Cavity of the Cranium a Shop for the Phrenologist – Way of disposing the vast Bulk of the Head – Surfeit of Birds and Capers of Sharks – Hazards and Toil of Whalemen little known by those whose Lamps they are lighting at Home – Oily Processes – Sperm Candle Manufactories – Avenues and Limits of New England Enterprise. 154CHAPTER XI.AUTHENTIC TRAGEDIES AND PERILS OF THE WHALING SERVICE.Contrasted Lights and Shadows, Good and Evil, in the Life of a Whaleman – Boats gone and Man Overboard – Dread Thoughts and Prospects – Phantasms of the Darkness – Return of the Boats and Loss of poor Berry – Horrible Discovery by a Whaler in the Seas of Greenland – A Charnel Ship – An awful Warning – Rime of the Ancient Mariner 164CHAPTER XII.YARNS FROM THE EXPERIENCE OF OLD WHALEMEN.An old Man's Yarn Spun out of the Recollections of Whaling Life in Youth – Boat tapped by a Whale – Lancing Deep – Captain and Boat-steerer plunged into the Brine – Way to mend a stoven Boat in an Emergency – Reward of Courage and Patience – Dead Spermaceti Whale – A Windfall to the Cremona – Exciting Chase for a Whale between Ships of four Nations – Romance of Rival Whaling – Victory to the American. 182 |

CHAPTER XIII.PECULIAR VOCABULARY AND HAZARDS OF WHALEMEN.Whaleman's Contribution for an Appendix to Webster's Dictionary – A Treatise on Gamming – Savory Comparisons – Appalling Forms of Danger encountered by Whalemen – Singular Exploit of a Bull Whale – Difference between rational Conjecture and melancholy Fact – Effect produced by Familiarity with Danger. 203CHAPTER XIV.REMARKABLE EVENTS IN THE ANNALS OF WHALING.Facts from which to estimate the prodigious Speed and Strength of the Whale – Terrible Destruction of the Essex by being run upon by a Sperm Whale – Sufferings and Fate of the Crew – Similar Catastrophe to the Union and a Merchant Brig – Remarkable Adventures and Escape – A lone Boat demolished by a Whale fifteen Miles from the Ship – Prayer of the doomed Mariners – Unexpected Deliverance – A Whale-boat driven into a Whale's Mouth – The Leap and the Rescue – A hard Life and the Characters it forms – The Virtues that are found growing in a Whale Ship – The Life to live. 211CHAPTER XV.CLAIMS AND ADVANTAGES OF THE SABBATH IN A WHALE SHIP.A flagrant Abuse of the Lord's Day – Estimated Number of Persons employed in the Whale Fishery – Sabbath-breaking Usages to which they are subjected on Board Ship – Sundry common Excuses in its Defense – Ten Propositions in Reply – Opposite Instances of Sabbath Breakers – The Godliness Satan is pleased with – Schoolcraft on the Sabbath – Zest after Rest – Charge to the Sabbath Keeper. |

CHAPTER XVI.A PLEA IN BEHALF OF THE SABBATH FOR WHALEMEN.The two Buttresses of Sabbath Whaling – Owners' Greediness of Gain – Lucre Stronger than Law – Testimony of an American Foreign Missionary – Silence of the Clergy in Whaling Ports – Inconsistency of Religious Revivals sending forth Sabbath-breaking Converts – Christianity giving Shelter to, and getting a Name from Sin – The Puritan's Praises oftener heard than the Puritan's Morals exemplified – Supposed Remonstrance of a Delegation of Pilgrims – Sabbath-keeping Experience of Captain Scoresby – Expostulation with Owners, Ship-masters, Seamen, and Others – A good Time coming. 244CHAPTER XVII.NEARING HOME AND ANALOGIES FROM THE SEA.Hopes and Fears on coming Home after being long away – Thickening Dangers at the Close of a Voyage – Pilgrim Land Light-house – The last Sermon on Shipboard – Evening Prayer-meeting – Pearl-findilg – Lesson from a Captain in Sounding – Spiritual Analogies – Fruits of the Voyage. 265CHAPTER XVIII.KNITTING UP THE LESSONS OF THE VOYAGE AT ITS CLOSE.Wrecks met with in the Gulf Stream like the Wrecks of old Opinions – Lesson learned from the Ship's Behavior in a Gale – Illustration of Faith from the Experience of a young Ship-master – Promises of God's Word like the Mariner's Life-lines – Analogy between the Albatross on a Ship's Deck and the Christian in Trial – Magnetism and Workings of Faith Illustrated by the Oscillations of the Mariner's Needle – Instruction from taking a Pilot – Painful Intelligence of the Doings of Death – Tribute to a departed Brother. 276 |

NOTES.Scenes in the Pacific – Former Fate of shipwrecked Mariners – A Ship with the Scurvy – How entertained, and why – The Change made by Missionaries – Reflections and Rememnbrances of a Boat-steerer – Boat's Crew lost in a Fog – The Loss and Recovery of three Boats on the Line belonging to the Harriet – Rights, and Wrongs, and Disabilities of common Whalemen – Sabbath-keeping Experience in the Whale Fishery of Rev. William Scoresby – Evidences of the Blessing of Providence upon the Observance of the Sabbath – Obvious physical Benefits as well as spiritual – Question considered whether a Whaling Captain should himself go in the Boats – The Danger and Inexpediency of it illustrated by Facts – Sufferings of Captain Hosmer and Boat's Crew of the Bark Janet – Narrative of the Destruction of the Ann Alexander by a Sperm Whale – Escape of the Pocahontas – Encounter of a Bull Whale with the Bark Parker Cooke. 291 |

|

|

There she blows! There she blows!

There she blows! There she blows!Man the boats! For nothing stay! Such a prize we must not lose! Lay to your oars! Away! away! |

LIST OF ENGRAVINGS

|

THE WHALE AND HIS CAPTORS; |

THE WHALE AND HIS CAPTORS.CHAPTER I.INTRODUCTION.

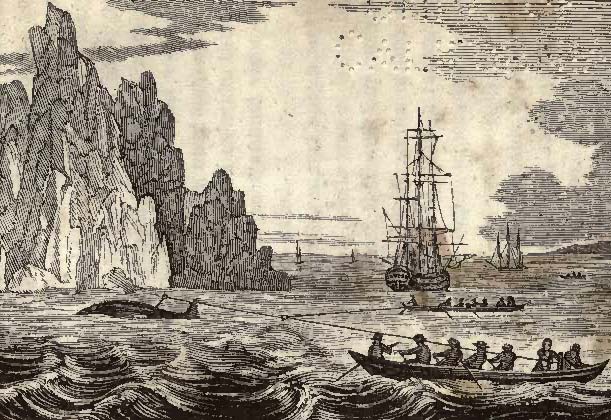

From very early times it is probable that Northwest Indians, Esquimaux, and Norwegians were in the habit of capturing whales in their rude way, in order to supply themselves with fat and food. There is a curious tradition extant of one Ochter, a Norwegian, who, as long ago as King Alfred's time, "was one of six that had killed sixty whales in two days, of which some were forty-eight, some fifty yards long." But the Biscayans are believed to have been the first people who prosecuted the whale fishery as a commercial pursuit, so far back as the twelfth century. In the north of Europe and all around the Bay of Biscay | |||||||||||

whale's tongues were among the table delicacies of the Middle Ages. When this branch of industry failed with them, by reason of whales ceasing to visit the Bay of Biscay, the English and Dutch, taught by the Biscayans,'who were best experienced in that facultie of whale-striking,' took it up in the Northern Seas, where the gigantic game was then every where found in vast numbers by navigators in search of the northern passage to the Indies. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Dutch had built the considerable village of Smeerenburg, on the Isle of Amsterdam, along the northern shore of Spitzbergen, within only eleven degrees of the North Pole, where the unbroken night is from September to March, and the day from March to September. This was the great rendezvous of Dutch whale ships, and it being their practice to boil the blubber on shore, it was amply provided with boilers, tanks, and all the apparatus then used for preparing the oil and bone. This fishing colony of the frozen zone, an incidental fruit of those daring adventures after a northeast route to India, was founded nearly at the same time with Batavia in the East, and | |||||||||

it was for a considerable time doubtful which of the two would be most important to the mother country. When in its most flourishing state, near 1680, the Dutch whale fishery employed two hundred and sixty ships and fourteen thousand seamen. This singular village and Bay of Smeerenburg, where there were seen at one time by the Dutch navigator Zorgdrager no less than one hundred and eightyeight vessels, afford, perhaps, the most remarkable instance on record of what commerce can do against unyielding laws of Nature, and over obstructions which it would seem impossible to surmount. But how soon does Nature, if ever temporarily displaced, resume her sway. Now that the whales have long since deserted those parts, even the site of the old Arctic colony is hardly discernible, and the English branch of the Greenland whale fishery is all that is prosecuted in those seas, and that with very moderate success. The first person that is recorded to have killed a whale among the people of New England was one William Hamilton, somewhere between 1660 and 1670. In the town records of Nantucket, there is a copy of an agreement entered | |||||||||

into in the year 1672, between one James Lopar and the settlers there, "to carry on a design of whale fishing." But whether the first proper whaling harpoon used in America was wrought there or on Cape Cod can not be ascertained. From this time onward, whenever whales were descried in the bay or offing from the rude look-outs constructed along shore, notice was instantly spread, and they were attacked by boats then manned mostly by the Indians, who early evinced an aptitude and fondness for this business. Shore-whaling seems to have reached its height by 1726, during which year eighty-six whales were taken, eleven in one day. It was continued with declining success up to 1760, and for seventy years preceding that date not a single white man is known to have lost his life in the hazardous pursuit. As early as 1700, they began to fit out vessels from Cape Cod and Nantucket to "whale out in the deep for sperm whales." These gradually crept along, emboldened by experience, north to the Labradors and south to the Bahamas, where New Providence became famous as a whale-fishing station, through the skill and daring of New England enterprise, while, as | |||||||||

Burke said, but in the gristle, and not yet hardened into the bone of manhood. By the year 1771, New England, through her adventurous whale fishery, was both in the North and South Atlantic Oceans, commanding the admiration of the world, and eulogized by the highest eloquence of the British Parliament From the year 1771 to 1775, Massachusetts alone employed in it annually three hundred and four vessels, of twenty-seven thousand eight hundred and forty-six tons burden. The quantity of oil brought into Nantucket yearly at the time of the breaking out of the Revolutionary war, was thirty thousand barrels. Stimulated by their success, both France and Great Britain now entered anew into this lucrative enterprise; Louis XVI. himself fitting out six ships from Dunkirk on his own account, in 1784, which were furnished with experienced harpooners and able seamen from Nantucket. In 1790, France had about forty ships employed in the fishery, but the wars consequent upon the French Revolution at once swept them all, and the whaling fleet of Holland also; as did the War for Independence likewise suspend this lucrative branch of the commerce of New | |||||||||

England. By reason of it, no less than one hundred and fifty of her vessels were either captured or lost at sea, and great numbers of her seamen perished. In 1788 Great Britain had the honor of opening the Pacific to the sperm whale fishery, through the Amelia, Captain Shields, fitted out at vast expense by Mr. Enderby, of London. Her unprecedented success started numbers on her track both from New England and Old, and by 1820 the whole South Pacific and Indian Oceans were traversed by intrepid whalemen; and in the seas of China and on the coasts of Japan they were drawing the line and striking the harpoon into those mammoth denizens of the deep. Prostrated, however, by the Revolutionary war, the New England branch of the whale fishery had hardly recovered its former prosperity, when the last war with Great Britain, from 1812 to 1815, again broke it up. But upon the restoration of peace its recovery was rapid; so that by 1821 there were owned in Nantucket alone (which had lost during the war twentyseven ships), seventy-eight whale ships, and six whaling brigs. In 1844, the entire American | |||||||||

whaling fleet amounted to six hundred and fifty ships, barks, brigs, and schooners, tonnaging two hundred thousand tons; and they were manned by seventeen thousand five hundred officers and seamen. At the same time, the English whale fishery, which in 1821 employed three hundred and twenty-three ships, was reduced to only eighty-five. But the New Holland branch of the English whale fishery was rapidly growing, the proximity of those whaling ports of Australia to some of the most productive cruising grounds enabling the ships fitted out there to perform three voyages while the English and Americans are performing two. The number of whale ships from French, German, and Danish ports, at the same time, was between sixty and seventy. The estimated annual consumption of the American whaling fleet was $3,845,500. Value of the annual import of oil and whalebone in a crude state $7,000,000, increased by manufacturing to $9,000,000. The number of vessels in the American whale fishery the present year, 1849, as gathered from the "Whaleman's Shipping List," is estimated at six hundred and ten, or one hundred and ninety-six | |||||||||

thousand one hundred and thirteen tons, nearly one tenth of the navigation of the Union. Receipts of sperm oil the last year, 1848, one hundred and seven thousand nine hundred and seventy-six barrels, at an import value of $3,455,232. Receipts of right-whale oil in the same time, two hundred and eighty thousand six hundred and fifty-six barrels, at an import value of $3,429,494. Whalebone, two million three thousand six hundred pounds, worth $508,762. Crude value of the whale fishery in 1848, $7,393,488. The average yearly quantity of sperm oil taken for nine years has been one hundred and forty-two thousand two hundred and forty-two barrels; of right-whale oil, two hundred and fifty-five thousand four hundred and fifty-six barrels; of bone, two million three hundred and twenty-four thousand five hundred and seventy-eight pounds. Average yearly value for nine years, $8,098,360. There was a falling off in 1848, from the previous year, of thirteen thousand barrels of sperm, thirty-three thousand barrels of right whale, and one million pounds of bone. Eighteen years ago it was estimated, by taking into account all the investments con- | |||||||||

nected with the American whale fishery, that property to the amount of $70,000,000 was involved in it, and that seventy thousand persons derived from it their chief subsistence; a valuation which should be much augmented rather than diminished at the present time. The New Bedford district now supplies to the whale fishery one hundred and two thousand three hundred and five tons. All other ports, including sixty-six ships, or twenty-three thousand tons from Nantucket, give ninety-three thousand eight hundred and eight, in all one hundred and ninety-six thousand one hundred and thirteen tons. The -exports of oil to foreign ports, in 1848, from New Bedford, were seventeen thousand and ninety-three barrels. To those who are in quest of definite information concerning the various cruising grounds and the times of finding whales there, the closing chapter of the Annals of the United States Exploring Squadron is the most satisfactory of any thing to be found. It should be printed in pamphlet form, and kept in the chart-box of every whaler. Other interesting matter, of a miscellaneous character, pertaining to the whale fishery, is to be found in the appendix to a work | |||||||||

of J. R. Browne, called "Etchings of a Whaling Cruise," and in a volume entitled "Incidents of a Whaling Voyage, by F. A. Olmsted." Without superseding or conflicting with either of those entertaining books, the course pursued in the present volume is an independent one, whereby it is aimed to finish the complement of whaling literature, and supply what was wanting, in order to put the reading public in possession of a full-length portraiture of the whaleman as seen in the actual pursuit and garb of his perilous occupation. Personal narrative and incident, other than what bears directly upon this, are therefore omitted, together with those minute descriptions of whaling implements, outfits, modes, customs, and seausages to be found elsewhere. Neither does it enter into our purpose to portray a sailor's life and manners in the forecastle or before the mast, alow or aloft, for this is a department of marine literature in which books are so numerous, both in the form of the novel and the sea journal, that little remains to be told. In adventures, however, almost every whaleman's voyage is an original, certainly so to himself. We begin, therefore, at once, with the peculiar | |||||||||

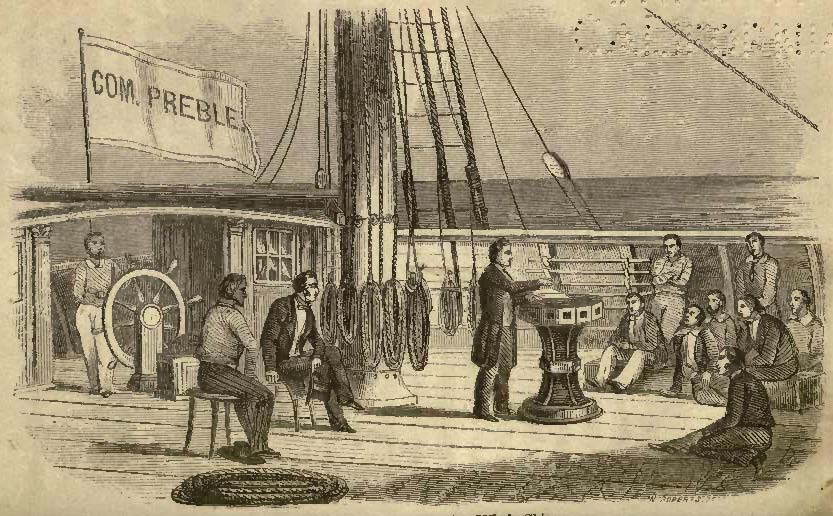

lights and shadows of a homeward cruise in the Pacific and Atlantic, from the Sandwich Islands to Boston, in the good ship Commodore Preble, Captain Lafayette Ludlow. In a voyage of two hundred and thirty-six days there will always be lights and shadows, good and evil, pleasures and displeasures, interlocking one another. To the author the comforts of this long voyage far exceeded its discomforts, by the constant blessing of Providence, making it eminently conducive to the recovery of health, and through the personal kindness of a skillful captain and esteemed friend. Would that every wanderer in quest of health could be cheerfully returning homeward under circumstances as favorable!

| ||||||||||

CHAPTER II.CORAL ISLAND OF RIMATARA.

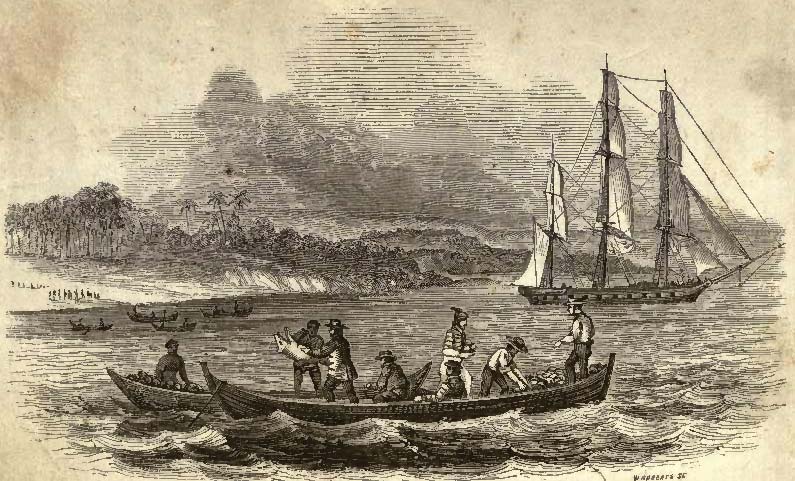

The first view we have of the Commodore Preble is as she is lying off and on the lone island of Rimatara, in quest of the fresh supplies which whalemen covet in order to keep at bay the scurvy. This is one of those fascinating South Sea Islands, which, on their first discovery by Europeans in the latter part of the last century, quite turned the heads of many, and at once started so much speculative nonsense and sentimentality about primeval in. nocence and bliss embosomed in the Pacific.

| |||||||||||

The Commodore Preble taking Supplies at Rimatara. |

It is about seven miles long, one and a half or two wide, and lies in 152º west longitude, and 22º 45' south latitude; about five hundred miles southwest from Tahiti. It is properly, perhaps, one of the Society Island group, being a mere pile of corallite and wave-washed coral sand. We came in sight of it on Tuesday afternoon, a blue hummock on the bosom of the ocean, and ran on until we discovered, to our great delight, what could not be mistaken for a meeting-house and a white flag flying on a post near by, to indicate the friendliness of the natives, and induce us to stop for trade. The sea broke so high upon the northeast and southwest points of the island, and, indeed, all along shore, that our captain did not deem it prudent to attempt landing that night. We therefore stood off until twelve o'clock midnight, and then tacking, were up with it again by ten o'clock next morning, on the leeward side. The island presented a beautiful appearance, being thickly wooded to the water's edge, and elevated in some parts into gentle hills, crowned with all the various and luxuriant growth of the tropics. Canoes soon launched out through the boisterous surf, and came alongside of us, | |||||||||

having two or three lads and men in each, much fairer-skinned and better looking than the majority of Hawaiians. The captain's boat anchored off the reef, while the natives brought their articles of trade in their pigmy canoes. By four in the afternoon he had procured a boat-load of pigs and cocoanuts, with which returning to the ship, we stood off again until next morning, when the captain gave orders for two boats. One of our sailors by the name of Johnson, that had lived on Tahiti,,and could talk a little in their tongue, had told the natives the day before that there was on board a missionary, or a missionary's friend, from Hawaii, and there was accordingly sent off through him, on a slip of paper, very legibly written by the native teacher, a Rimatara letter, of which the following is a literal translation: "Dear Friend and Father, – "May you be saved by the true God. This is our communication to you. Come thou hither upon the shore, that we may see you in respect to all the words of God which are right with you. It is our desire that you come to-day. "From Teutino and his brethren." | |||||||||

Eager to know something more of a people from whom came so cordial an aloha, and

I made ready to go ashore. The breakers were not formidable enough, though beating with fearful violence, to make me forego the novelty of setting foot on a coral South Pacific island, and the pleasure of a stroll among the trees after seven weeks at sea. Taking, therefore, a life-preserver, I ventured into one of the little canoes that came alongside the boat, and was paddled and handed by a narrow cleft, through roaring breakers and ragged rocks that threatened instant destruction, among which a common boat could hardly live a moment. Those frail canoes, however, only nine and eleven feet long, carried safely through, one by one, all that ventured ashore. Immediately on our landing, the natives gathered around and formed a ring, naturally curious, like savages every where, to notice every thing, and I not less so to observe their own eager attitudes, expressive gestures, and fine looks. The women have an uncommonly pleasing aspect of countenance, clear skin, but | ||||||||||

a shade or two darker than a dark brunette, black eyes, hair, and eyebrows, and a captivating beauty of form, and bashful turning away when looked at, that is not a little attractive. Their nostrils are not so negro-like, nor their lips so thick as those of the Hawaiians, but still they bear to them a close resemblance. Many of the little girls and maidens were truly beautiful, and would be deemed paragons, even in the artificial state where beauty is not left so much to itself, but has to be busked, bustled, and corseted by omnipotent fashion. I soon made my way to the island king, Temaeva, who sat apart from others upon a block of coral, and leaning on a staff, his only dress being a shirt and kihei (mantle). He was a benevolent-looking, well-made man, having the port and presence of a king, and, if that were all,

He offered me his hand with much apparent cordiality, and immediately led the way to his house in the interior. The path was at first rugged as the volcanic clinkers of Hawaii, over heaps and swells of broken and sharp coral, overgrown with huge roots of the Kamani and | ||||||||||

Koa trees, in the borrowed terms of Wordsworth,

This barrier passed, there was a subsidence and inclining of the island inward, and the path went through a meadow of bulrushes, in time of rain flooded. The soil was a rich black loam. Next came beds of wet kalo (Arum esculentum), very luxuriant and large, beyond which were the houses of the king and native missionary teachers, the chapel, school-house, and principal settlement. These were prettily-made buildings of kamanu posts, wattled between, lined on both sides with a good coat of whitewashed plaster, and thatched on the roof with grass. Being clustered tastefully together, they make a very pleasing appearance outside. The chapel and house of the king were furnished with flooring and settees. In the former was a round pulpit, very much like those seen in popish cathedrals, wherever is seen at all what popery is by no means fond of-the pulpit. They had been built eleven years, it being more than twenty, we were told, since the isl- | ||||||||||

and was first Christianized by native missionaries from Tahiti. They were all surrounded by a low paling of posts driven slightly into the ground, merely to keep out hogs; while cocoanut trees and giant bananas were dropping their fruits all around. The whole scene, in every feature, was most pleasingly corroborative of the representations quoted by Harris in "The Great Commission," to show the temporal utility of missionary exertions in the South Seas. "Instead of their little, contemptible huts along the sea-beach, there will be seen a neat settlement, with a large chapel in the center, capable of containing one or two thousand people; a schoolhouse on the one side, and a chief's or the missionary's house on the other; and a range of white cottages a mile or two long, peeping at you from under the splendid banana-trees or the bread-fruit groves. So that their comfort is increased and their character elevated." Soon after reaching this little metropolis of the island, the king had baked pig and delicious kalo placed upon a massive rude table, and plates of English crockery, with knives and forks. A blessing was asked by the native teacher, and I was invited to eat. It was, in their view, an im- | |||||||||

portant piece of courtesy, which a recent breakfast rather unfitted me for; yet I ate, with compliments, of the mealy kalo, and tasted of the pig, while the king was taking huge morsels that would almost sink a common man. The wine of this feast was the delicious milk of young cocoa-nuts just from the tree; and I will venture to say that Hebe never poured such nectar into the goblets of the gods. It was more like that which Eve made ready once in Eden, as the poet tells, wherewith to entertain their angel guest:

This entertainment over, we repaired to the teacher's, where again was served up the same. with the addition of banana made into a poi, of which the king ate freely. I was here presented with a couple of rolls of white kapa by the good woman of the house. After surveying the premises, getting a specimen of the king and teacher's handwriting, and giving them a card to certify any other chance ship of their hospitality, I returned to the shore by another path, | |||||||||||||

through a dense wood, coming out of it on the windward side of the island, by the old church and grave-yard, where Temaeva pointed out the tomb of a former wife, having the date of her death rudely cut in a coral slab. The cocoa-nuts passed were numberless, shedding their fruit by thousands; also lofty and straight pandanuses, kukuis, and milo trees. Following round the shore to the point at which we had struck off into the woods, we found the captain there busy trading. I pleased myself a while with looking at those mixed and motley groups, and trying to communicate with the harmless Arimatarians, and then went off to the boat through the outrageous surf, inly wishing I could leave with them some substantial and enduring testimony of good will. The king and his wife, together with the captain, came, one by one, soon after, and we all pulled off to the ship, where the king seemed highly gratified with his entertainment and presents. He is manifestly king but in name, having to promise a recompense even to the men that brought him off to the boat in their canoe. The Gospel has abolished all tyranny, and, as the sailor interpreted it, all there are for them- | |||||||||

selves, and without distinctions. They are four hundred all told, and live, according to their own telling, in much peace, being visited two or three times a year by whale ships for recruits, whose trade just keeps them (the adults) with a single cloth garment, or kihei a piece. A roughly-made schooner, of kamanu wood (much like our mahogany), was on the stocks, for which they were very anxious to get tar, oakum, and a compass. No white missionary, we were told, has ever resided upon the island, but all their imperfect Christianization and acquaintance with the arts have been effected by native teachers from Tahiti. White men have stopped on the island occasionally, but they say they do not want them, unless they know the language and have some trade. I could not leave this secluded and lovely isl. and, though but the stopping-place of a day, and ere long, I hope, to mingle with humanity in a wider and more populous field, without a feeling of sadness, I hardly know why. But so it is in the voyage of life, especially in that of a traveler, sailing down the stream of time, we hail a friendly bark, or touch here and there at a pleasant landing-place upon its banks, pluck | |||||||||

a few fruits and flowers, exchange good wishes and kind words with the friends of a day, truly love and are loved by some congenial hearts, both drop and take some seeds of good and evil, to spring up when we are in our graves, and then we are away; the places that now know us know us no more forever, and the faces that now smile upon us we never see again. Who can help sighing as he thinks of it, and wishing to leave, wherever he goes, some durable evidence that an immortal spirit has passed that way!

| ||||||||||

How different now our reception here by Islanders that had been blessed with the Bible, from that which a whale ship had while sailing along in this same Pacific in the year 1835, from barbarians that had never received the Gospel. A large number of natives came off, as to us, for purposes of trade. No treachery was suspected, and all for a while went on amicably. But, upon a signal from a chief, the natives sprang for the harpoons, whale-spades, and other deadly weapons at hand, and a desperate contest immediately ensued. The captain was killed by a single stroke of a whale-spade; the first mate also, soon after. The second mate jumped overboard and was killed in the water, and four of the seamen lost their lives. A part of the crew ran up the rigging for security, and the rest into the forecastle. Among these last was a young man, the third mate, by the name of Jones, the only surviving officer. By his cool intrepidity and judgment, after a dreadful encounter, the ship was cleared of the savages, the chief killed, and many of his companions, both of those on board and those who came alongside to aid in securing the ship. Jones now became the captain, buried the | ||||||||||||

dead, dressed the wounded, put the ship in order, and made sail for the Christianized Sandwich Islands with the surviving crew. With a skill and self-possession worthy of the man that could accomplish such a rescue, and with a favoring Providence, he navigated the bereaved whaler to Oahu, where the survivors were hospitably entertained. The ship, however, had to be sent home, the voyage being completely broken up for want of the necessary officers, and thousands of dollars lost to owners and underwriters. I remember once to have listened to the narrative of a captain who was wrecked in the Pacific on a sunken rock, and for fourteen days and nights himself and crew, twenty-two in number, were exposed in their boats, and had quite given up hope of ever again reaching the land. But on the morning of the fifteenth day after the loss of their ship, they found their boats nearing an unknown island. They were almost spent, and saw the shore, which was guarded by a reef, lined with natives, whether cannibals or Christianized they could not tell. While their lives were in doubt, and they were questioning whether a worse death by | |||||||||

savage violence did not await them than if they had perished at sea, one of the natives came out toward them through the surf, hold. ing in his hand a book, and cried, with a loud voice, "Missionary! missionary!" An answering shout of recognition and beckoning from the poor mariners immediately brought the natives, through the waves, to their aid, by whom they were carried on shore in their arms, supplied with food, and generously entertained with more than human, with Christian kindness. It so happened, according to the captain's statement, that this was an island whose inhabitants had been first brought to the knowledge of Christianity by the brother of this captain, who had been some years before cast away on this very island, and, with one other of the ship's company, was saved. They were taken by the natives to be offered up as a sacrifice to their gods. But while on their way to the place where human victims used to be sacrificed, they remembered the tradition that a god should come to them from the sea. Overruled, doubtless, by a divine impulse, they now entertained the white man as a god, and he instructed them concerning the only | |||||||||

true God and Savior. They invited the missionary from another island, and in Heaven's blessing upon his instructions was read the secret of all their after-kindness to the white men who visited or were cast upon their shores. All whalemen may see in this contrast, as we have to our joy in the Commodore Preble, what a difference there is between islands that have, and that have not the "BOOK." It is THE BOOK which has brought it to pass that the adventurous, weary whaleman can now traverse the entire Pacific, and land with impunity at most of its lovely islands, and be supplied on terms of equity with all he needs. Let, then, those that owe to it the most, be loudest in their praises, and warmest in their love, and most careful in their obedience to the BOOK OF BOOKS. It was the reasoning of one of this great family of South Sea Islanders (with whom our ship has just had such pleasant intercourse), soon after he came into possession of the BIBLE: When I look at myself, I find that I have hinges all over my body. I have got hinges to my legs, my jaws, my feet, my hands. If I want to lay hold of any thing, there are hinges | |||||||||

to my hands, and even to my fingers, to do it with. If my heart thinks, and I want to make others think with me, I use the hinges to my jaws, and they help me to talk. I could neither walk nor sit down if I had not hinges to my legs and feet. All this is wonderful. None of the strange things that men have brought from England in their big ships are at all to be compared to my body. He who made my body has made all those clever people, who made the strange things which they bring in the ships; and he is God, whom I worship. But I should not know much more about him than as a great hinge-maker, if men in their ships had not brought the book which they call the Bible. That tells me of God, who makes the skill and the heart of man likewise. And when I hear how the Bible tells of the old heart with its corruption, and the new heart, and a right spirit, which God alone can create and give, I feel that his work in my body and his work in my heart fit each other exactly. I am sure, then, that the Bible, which tells me of these things, was made by him who made the hinges to my body. I believe the Bible to be the word of God. | |||||||||

The men on the other side of the great sea used their skill and their bodies to make ships and to print Bibles. They came in ships, and brought iron hoops, knives, nails, hatchets, cloth, and needles, which are very good. They also brought rum and whisky, which are very evil. They moved the hinges of the jaws, and told lies and curses, which are abominable. At last some came and brought the Bible. They used the hinges of their bodies to turn over its leaves and to explain God's blessed word. That was better than iron-ware and stuff for clothing. They were the servants of the living God, and my heart opened to their words as if it had hinges too, like as my mouth opens to take food when I am hungry. And my heart feels satisfied now. It was hungry, God nourished it; it was thirsty, God has refreshed it. Blessed be God, who gave his word, and sent it across the sea to bring me light and salvation! Now we say that this unsophisticated native thinker, working thus all by himself at the great theological argument from evidences of design; could hardly have done better had he been going to school to Calvin or Chalmers all his days. He might have written in his Poly- | ||||||||||||

nesian Bible the lines which are said to have been found on the blank leaf of a copy of the Scriptures belonging to a great English poet. And, ah! how much better had it been for the world if Byron had loved his Bible as there is reason to believe the unknown Tahitian did his.

| ||||||||||

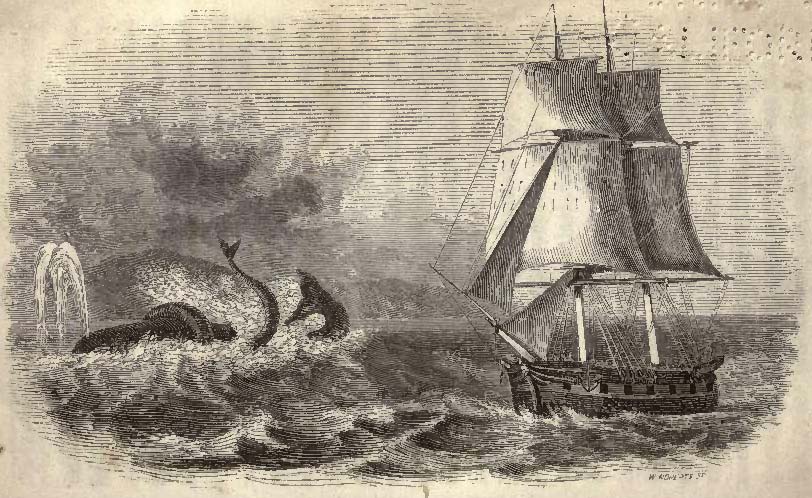

CHAPTER III.RAISING AND CUTTING-IN WHALES.

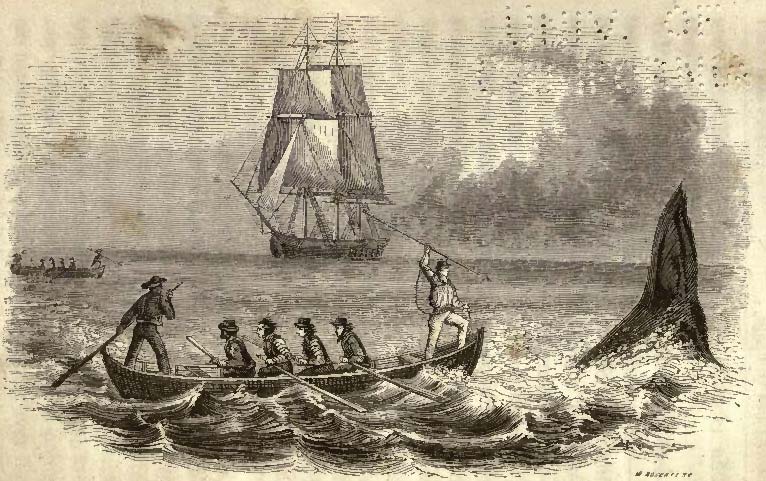

For the first time in our now ten weeks' passage from the Hawaiian Islands, on this New Zealand Cruising Ground, we heard, day before yesterday, that life-kindling sound to a weary whaleman, THERE SHE BLOWS! The usual questions and orders from the deck quickly followed. "Where away?" "Two points on the weather bow!" "How far off?" "A mile and a half!" "Keep your eye on her!" "Sing out when we head right!" It turned out that three whales were descried from aloft in different parts, and in a short time, when we were deemed near enough, the captain gave or. ders to "Stand by and lower" for one a little more than half a mile to windward. | ||||||||||

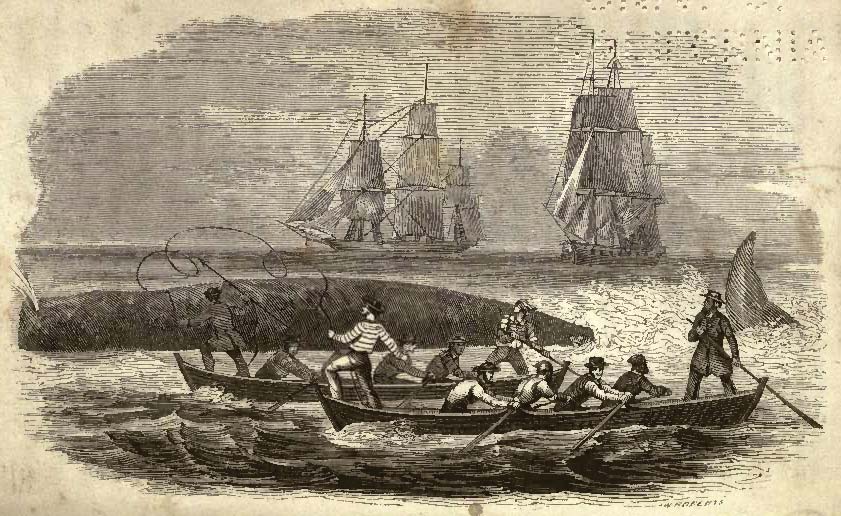

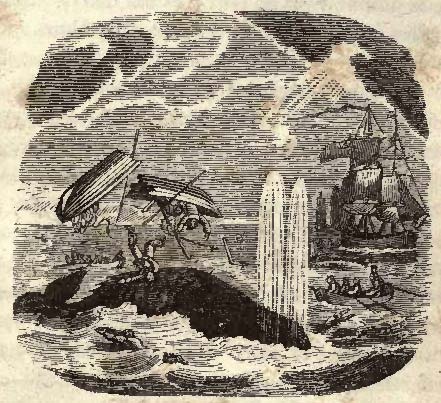

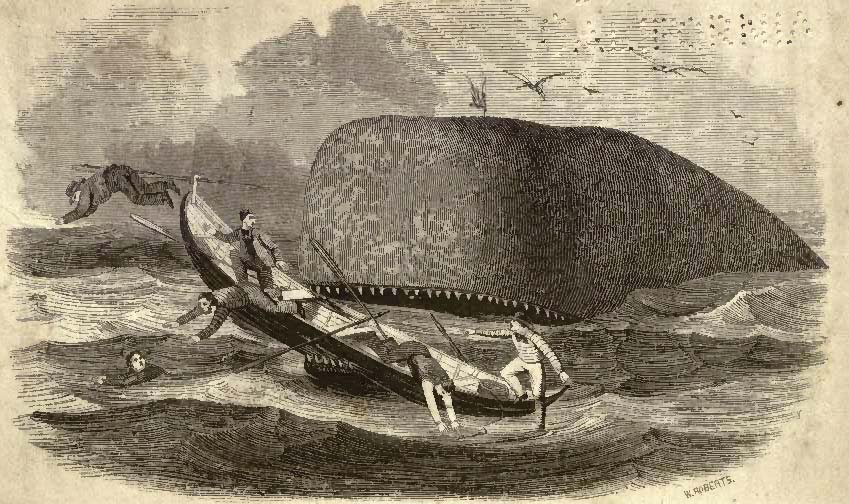

Three boats' crews pulled merrily away, glad of something to stir their blood, and with eager hope to obtain the oily material wherewith to fill their ship and make good their "lay." The whale was going leisurely to windward, blowing every now and again two or three times, then "turning tail," "up flukes," and sinking. The boats "headed" after him, keeping a distance of nearly one quarter of a mile from each other, to scatter (as it is called) their chances. Fortunately, as the oarsmen were "hove up," that is, had their oars a-peak, about the place where they expected the whale would next appear, the huge creature rose hard by the captain's boat, and all the harpooner in the bow had to do was to plunge his two keen cold irons, which are always secured to one tow-line, into the monster's blubber-sides. This he did so well as to hit the "fish's life" at once, and make him spout blood forthwith. It was the first notice the poor fellow had of the proximity of his powerful captors, and the sudden piercing of the barbed harpoons to his very vitals made him caper and run most furiously. The boat spun after him with almost the swiftness of a top, now diving through the seas | ||||||||||||

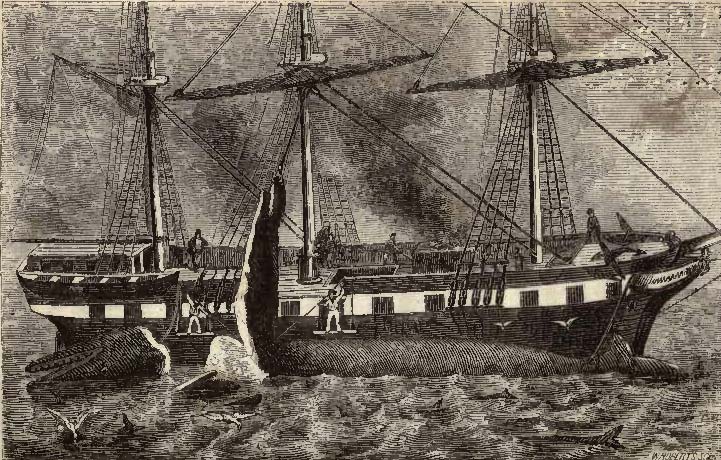

and tossing the spray, and then lying still while the whale sounded; anon in swift motion again when the game rose, for the space of an hour. During this time another boat "got fast" to him with its harpoons, and the captain's cruel lance had several times struck his vitals. He was killed, as whalemen call it, that is, mortally wounded, an hour before he went into "his flurry," and was really dead or turned up on his back. The loose boat then came to the ship for a hawser to fasten round his flukes; which being done, the captain left his irons in the carcass and pulled for the ship, in order to beat to windward, and, after getting alongside, to "cut him in." This done, and the mammoth carcass secured to the ship by a chain round the bitts, they proceeded to reeve the huge blocks that are always made fast for the purpose to the fore and main mast head, and to fasten the cutting-in tackle. The captain and two mates then went over the sides on steps well secured, and having each a breast-rope to steady them and lean upon. The cooper then passed them the long-handled spades, which he was all the time grinding and whetting, and they fell lustily to work chopping off the blubber. | ||||||||||||

View of a Whale Ship in the Process of "Cutting in."

View of a Whale Ship in the Process of "Cutting in."

|

First came one of the huge lips, which, after they had nearly severed close to the creature's eye, was hooked into by what they call a blubber hook, stripped off, and hoisted on board by the windlass. It was very compact and dense, and covered with barnacles like Brobdignag lice. Next came one of the fore-fins; after that the other lip, and then the upper jaw along with all that peculiar substance called whalebone, through which the animal strains his food. It is all fringed with coarse hair that detains the little shrimps and small fry on which the creature feeds. The bones, or, rather, slabs of whalebone radiate in leaves that lie edgewise to the mouth, from each side of what may be called the ridge-pole of the mouth's roof, forming a house almost big enough for a man to stand up in. Outside it is crowned with what they call a bonnet, being a crest or comb where there burrow legions of barnacles and crabs like rabbits in a warren, or insects in the shaggy bark of an old tree. Next came the lower jaw and throat, together with the tongue, which latter alone must have weighed fifteen hundred or two thousand pounds; an enormous mass of fat, not, however, so firm and tough as the blubber. Whalers | ||||||||||||

often have to lose it, especially from the northwest whale, it being impossible to get it up on deck detached and alone, because it would not hold, and it is generally too large and heavy to raise along with the throat. After this was hoisted in, the rest of the way was plane sailing, the blubber of the body being cut and peeled off, in huge unbroken strips, as the carcass rolled over and over, being heaved on by the windlass, then hooked into by the blubber hooks, and hoisted in by the men all the time heaving at the windlass. As often as a piece, nearly reaching to the top of the main mast, was got over the deck, they would attack it with great boarding-knives, and cutting a hole in it at a place nearly even with the deck, thrust in the strap and toggel of the "cutting blocks," that they might still have a purchase on the carcass below. Then they would sever the huge piece from the rest, and lower it down into "the blubber-room" between decks, where two men had as much as they could do to cut it into six or eight pound pieces and stow it away. It was from nine to eleven inches thick, and looked like very large fat pork slightly colored with salt-petre. | ||||||||||||

The magnificent, swan-like albatrosses were round us by hundreds, eagerly seizing and fighting for every bit and fragment that fell off into the water, swallowing it with the most carnivorous avidity, and a low, avaricious greed of delight, that detracted considerably from one's admiration of this most superb of birds, just as your veneration for one whom the coloring of a youthful imagination has made a little more than human, is not a little abated by finding him subject to the necessities and passions of poor human nature. Gonies, stinkards, horsebirds, haglets, gulls, pigeons, and petrels, had all many a good morsel of blubber. For at any time in these seas, though eight hundred or a thousand miles from shore, the capture of a whale will allure thousands of sea-birds from far and near. Sharks, too, appeared to claim their share; but it was not until after a man had been down twice on the wave-washed carcass, to get a rope fast to a hole in the whale's head, or I should have trembled for his legs. Before the blubber was all off, the huge entrails of the whale burst out like barrels, at the wounds made by the spades and lances. I hoped the peeled carcass would float for the | ||||||||||||

benefit of the gonies and other birds. But no sooner was the last fold of blubber off, the flukes hoisted in, and the great chain detached, than it sank plumb down. About the same time two ships bore down to speak us, the Henry of Sag Harbor, and the Lowell of New London. Their captains came on board to congratulate us on our success, and "learn the news." They had just arrived on the ground, and had not yet taken any whales. Soon after we had finished cutting in, about eight o'clock in the evening, the wind increased almost to a gale, making it impossible to try out that night. But to-day, while the ship is lying to, the business has begun in good earnest; the blubber-men cutting up in the blubberroom; others pitching it on deck; others forking it over to the side of the "try-works;" two men standing by a "horse" with a mincing knife to cleave the pieces into many parts for the more easy trying out, as the rind of a joint of pork is cut by the cook for roasting: the boatsteerers and one of the mates are pitching it into the kettles, feeding the fires with the scraps, and bailing the boiling fluid into copper tanks, from which it is the duty of another to dip into casks. | |||||||||

|

Whaling Implements.

1. Hand Harpoon. 2. Pricker. 3. Blubber Spade.

1. Hand Harpoon. 2. Pricker. 3. Blubber Spade.4. Gun Harpoon. 5. Lance. |

The decks present that lively though dirty spectacle which whalemen love, their faces all begrimed and sooty, and smeared with oil, so that you can not tell if they be black or white. A farmer's golden harvest in autumn is not a pleasanter sight to him, than it is to a whaler to have his decks and blubber-room "blubberlog," the try-works a-blazing, cooper a-pounding, oil a-flowing, every body busy and dirty night and day. Donkey-loads of Chilian or Peruvian gold, filing into the custom-house at Valparaiso and Lima, or a stream of Benton's yellow-boys flowing up the Mississippi, or bags of the Californian dust riding into San Francisco, have no such charms for him as cuttingin a hundred-barrel whale and turning out oil by the hogshead. The whale now taken proves to be a cow whale, forty-five feet long and twenty-five round, and it will yield between seventy and eighty barrels of right whale oil. This is about the ordinary size of the New Zealand whale, a mere dwarf in comparison with that of the northwest, which sometimes yields, it is said, three hundred barrels, ordinarily one hundred and fifty, or one hundred and eighty. | |||||||||

Though so huge a creature, a very small part of its bulk appears out of water, and that bending with the undulations of the waves; nor do you have so fair a view of this immense mass of organized matter, as of a ship afloat in comparison to one on the stocks. To have a just idea of its greatness, it should be seen on dry land. As is usually the case, the observed reality of this mammoth animal, prodigious as it is, hardly comes up to the preconceived vague idea of it, still less to the poetic notion of

They used to tell some big "fish stories" in Milton's day, and I have no doubt they had something to do in his mind with the creation of that image of Satan on the burning lake.

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||

CHAPTER IV.NEW ZEALAND CRUISING GROUND.

The recent capture of one right whale, getting fast to another, and pursuit of several more, and the sight of them blowing all around, close at hand and at a distance, naturally puts one upon inquiring into the habits and resorts of this great sea-monster. It is of the class mammalia, order cetacea, warm-blooded, bringing forth its young alive, generally one at a time, and giving them suck. It is not, therefore, a fish, is without scales, breathes the air through enormous lungs, not gills, and respires by what is called its spout or blow-holes, a kind of nostrils, or, in other words, two apertures | ||||||||||

situated on the after part of its head and neck, through which is forcibly expelled all the water taken into the mouth in the act of feeding and breathing, and all the warm air and vapor of the lungs. The form of the spout serves to distinguish at a distance the kind of whale, whether right whale (Baluena mysticetus) or sperm (makrocephalus). The right whale, having two large orifices on the top of the back part of its head as it lies along in the water, the spout of vapor and water ejected is forced up perpendicularly till its power is spent, and it begins to fall over on both sides, looking then, at a distance, in shape like a Gothic elm parted into two branches. This can be easily perceived when the whale is either coming directly toward or going directly off from the ship, the jets d'eau being sometimes thirty or even fifty feet high. The sperm whale, on the other hand, has but one blowhole, and that a little on one side or corner of its head, from which the ejected stream of breath issues a little obliquely, and not straight up, as in the right whale. Being only the confined air of the lungs, and condensed into a white mist, it vanishes instantly. | |||||||||

Its propellers and means of defense are two fins, planted a little behind the head on each side, and the flukes of its tail, also, with which it sculls and attempts to strike its enemy. The juncture of these flukes with the main body of the whale is comparatively small, and a skillful whaler always tries to cut the tendons, like a hamstring, with his spade when the whale is violent. If successful in this, the flukes will be still, and the danger of approaching the whale greatly diminished. The natural working of them on their joints by the waves, after the animal is dead, will always carry the carcass directly to windward. Of one that I have measured, the fins were five feet long each, and the flukes twelve feet across, horizontally. Of another the body was thirty-nine feet long and nineteen feet round, the head seven feet from its tip to the spout holes, three feet wide just behind the same, and three feet from the upper outside superficies to the roof of the mouth inside, making its entire head, with the mouth closed, seven feet in diameter, or twenty-one feet round. The length of another, which I have exactly measured, a sperm whale, was fifty-nine feet, and thirty round. | |||||||||

The ear of the whale is extremely small, and so hidden, like a mole's, that you would not find it without diligent search. Still the creature is thought by seamen to be quick of hearing as well as sharp of sight. The organ for the latter sense is about as large as the eye of an ox. The head of a right whale, when his mouth is open in feeding, or when he breaches, as I have sometimes seen him do quite out of water, is a most uncouth and formidable sight. It looks at a little distance like the black, rugged mouth of one of those lava caverns a traveler meets with on the Island of Hawaii. The huge lips close from below upward, and shut in, when the monster has got a mouthful, upon his immense whalebone cheeks, like the great valve of a mammoth bellows, or the water gates of a canal lock. The sole living of this vast animal is thought to be upon a substance which I hear universally called by whalemen "right whale feed" (medusae). It appears in the water like little red seeds of the size of mustard, which is intrapped by the hair that fringes the leaves of whalebone, as the whale swims along with mouth open. It is, in fact, a little red shrimp, | |||||||||||||||

sometimes seen floating on the surface in these seas alive, oftener dead, when it has the appearance at a distance of clots of blood, only yellower. I have seen it in both states, and as entangled in the hair of dead whales. The quantity necessary for the animal's support must be prodigious. I can doubly appreciate now that amusing passage in the Holy War, where Bunyan says, "Silly Mansoul did not stick nor boggle at a monstrous oath that she would not desert Diabolus, but swallowed it without chewing, as if it had been a sprat in the mouth of a whale." This feed is supposed to lie generally rather deep under water in these seas, as whales are often taken in greatest numbers where none of it is to be seen on the surface. In the Greenland and Arctic Seas it often covers miles and miles in extent, thick enough, it is said, to impede the course of a ship; and perhaps, in the economy of Providence, whales as well as sharks are but the scavengers of the great deep, to consume what would otherwise putrefy and decay. A volume of the Family Library, on "Polar Seas and Regions," which I have been reading with great interest on shipboard, says, that the | |||||||||

basis of subsistence for the numerous tribes of the Arctic world is found in the genus medusa, which the sailors graphically describe as seablubber. The medusa is a soft, elastic, gelatinous substance, specimens of which may be seen lying on our own shores, exhibiting no signs of life, except that of shrinking when touched. Beyond the Arctic Circle it increases in an extraordinary degree, and is eagerly devoured by the finny tribes of all shapes and sizes. By far the most numerous, however, of the medusan races are of dimensions too small to be discovered without the aid of the microscope, the application of which instrument shows them to be the cause of a peculiar color, which tinges a great extent of the Greenland Sea. This color is olive-green, and the water is opaque compared to that which bears the common cerulean hue. "These olive waters occupy about a fourth of the Greenland Sea, or above twenty thousand square miles, and hence the number of medusan animalcula which they contain is far beyond calculation. Mr. Scoresby estimates that two square miles contain 23,888,000,000,000,000; and as this number is beyond the range of hu- | |||||||||

man words and conceptions, he illustrates it by observing, that eighty thousand persons would have been employed since the creation in counting it. This green sea may be considered as the Polar pasture ground, where whales are always seen in greatest numbers. These prodigious animals can not derive any direct subsistence from such small invisible particles; but these form the food of other minute creatures, which then support others, till at length animals are produced of such size as to afford a morsel for their mighty devourers. "The genus cancer, larger in size than the medusa, appears to rank second in number and importance. It presents itself under the various species of the crab, and, above all, of the shrimp, whose multitudes rival those of the medusa, and which in all quarters feed and are fed upon. So carnivorous are the propensities of the northern shrimps, that joints of meat hung out by Captain Parry's crew from the sides of the ship were in a few nights picked to the very bone, and nothing could be placed within their reach except bodies of which it was desired to obtain the skeleton. Many of the zoophytical and molluscous orders, particularly Ac | |||||||||||||||

tinia sepia, and several species of marine worms, are also employed in devouring and affording food to various other animals." We learn, then, that the law of mutual consumption holds throughout the wide domain of the deep. And Byron was literally correct when saying, in his apostrophe to the Ocean,

The internal anatomy of a whale is to me a subject of great curiosity, and I wish it were in my power to report a full and accurate, leisurely post-mortem of the subjects we have discussed. But a few clinical notes, roughly taken by the bed-side, as the whalemen have been operating between wind and water with their professional spades and lances of dissection, are all I have to exhibit. From the barrel-like size of the protruding intestine of the last we have dissected, or more properly peeled, it is reasonable to infer by the law of relative proportions on which Agassiz constructs a fish from a single scale, that the great aorta of one of the largest kind of whales can be but little less in diameter than the bore of the main pipe of the Croton water-works; and the water roaring in | ||||||||||

its passage through that pipe must be inferior in impetus and velocity to the blood gushing from the whale's great heart, when his pulse beats high in the conflict with his captors. In Dr. Hunter's account to the Philosophical Society of the dissection of a small whale cast upon the coast of Yorkshire, this aorta measured a foot in diameter. In that case, fifteen or twenty gallons of living blood are ordinarily thrown out of the heart of a large whale at a stroke, with an immense velocity, through the great bore of a blood-vessel, or rather blood aqueduct, a foot or two in diameter. How it is, then, that, with such a prodigious current of blood constantly flowing and needing, oxygenization by the air, the whale can remain under water so long, respiration suspended (sometimes, in the case of a sperm whale, an hour and a half), it was difficult to conceive, until dissection discovered that in the cetaceous animals, the arterial blood, instead of passing into the venous circulation, the ordinary way, has interposed, by the Creator's providence, a structure which is nothing less than a grand reservoir for the reception of a great quantity of arterial blood, which, as occasion requires, is | |||||||||

emptied into the general circulation, and thus for a time supersedes the necessity of respiration. It may be that the accidental piercing, now and then, of the walls of this great penstock of arterial blood, by the harpoon or lance, has something to do with the whale's occasional sinking after being killed, a phenomenon not yet satisfactorily explained. Until within a few years this gigantic game has been every where so abundant that whalemen have used no means to keep their rich prizes from sinking; but when one has gone down worth $1500 or $2000, or even $3000, they have taken it as a whaleman's fortune, and have gone to capturing others instead. In some voyages they say more whales have been sunk than have been saved. The useless devastation thus caused among these huge denizens of the deep has been very great. One practical whaleran calculates the number of whales killed in one season on the northwest coast and Kamtschatka at 12,000. Would whalemen go provided with Indiarubber or bladder buoys, ready to be bent on to harpoons and darted into a whale's carcass as soon as "turned up," or when he is perceived | |||||||||

to be going into "his flurry," we are persuaded that many thousands of barrels of oil might be saved, and not a few poor voyages would be made good ones. According to Commander Wilkes's Narrative of the United States Exploring Squadron, the Indians of the northwest coast take quite a number of whales annually, by having their rude fish spears fastened to inflated seal-skin floats, four feet long and one and a half or two feet broad, that keep the whale on the top of the water, and allow him to fall a comparatively easy prey. The same thing used to be effected by the Indians of Cape Cod, having their fish spears fastened to blocks of wood, in lieu of which sperm whalemen now use what is called a "drag." Now that whales are getting scarce, we think it impossible but that Yankee sense and forehandedness will soon see to this, and go prepared against such disheartening catastrophes as losing their game by its sinking, after unsurpassed skill and daring have made it fairly their own. If owners knew how much might be saved by it, they would never let a ship go from port without buoys to hold up dead whales, and long hawsers to lay-to with by them in gales of wind. |

The Commodore Preble has lost, in the course of this voyage, seven by sinking after they were "turned up," and three from alongside in rugged weather, because without a long and strong hawser to secure them by to windward while lying-to. Six of our boats were stove in one season on the northwest coast, some of the crew were badly hurt, and the men got so afraid of a whale, that some of them would hide away when the order was given to lower. The only cause I have ever heard assigned for the right whale's sinking so often, is having the air-vessel which Nature is thought to provide this animal with, pierced by the lance or harpoon. Any one can see that a few buoys fastened to them would counterweigh this tendency to sink. I have even heard of their being hauled up when out of sight by four boat's crews pulling upon the tow-lines that were fast to the harpoons buried in the sinking carcass. Till we know more of the natural history of the whale than we yet do, its sinking so apparently without law can not be certainly accounted for. One whaleman says that he has known a whale of the largest size, which, in cutting him in, proved to be a dry-skin, that is, | |||||||||

the blubber containing a milky fluid instead of oil, and yet the whale floated as light as a cork. Again, he has killed a whale with a single lance, and he sunk like a stone, and another has sunk after lancing a hundred times. An ingenious Frenchman, I am told, in these seas, once rigged swivels in the heads of his boats, and had bladders and other gear to float dead whales; but he succeeded with it all so poorly, that, in mortification and despair, when he put into one of the ports of New Zealand, he went out into the woods and shot himself with a brace of pistols through both his eyes. I think some quick-witted Yankee would do better to give his attention to experimenting in this line; and, even if the whales would not be killed or floated, he would not be such a fool as to blow his own brains out. It is a true saying of Massinger:

Which, forasmuch as the crime is becoming popular nowadays, it would not be amiss to put a stop to, by enacting a law, as they once did in ancient Rome, to expose the body of every suicide naked in the market-place after death. | ||||||||||

CHAPTER V.THE WHALE'S PHYSIOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY.

There are some points in the whale's physiology, and in the way of disposing of the blubber, not noted in previous chapters, which are so well described in parts of a sailor's yarn that I have found in a loose number of the Sailor's Magazine, of which most excellent periodical we have several on board, that I will take from it here and there, with corrections, what may be wanting to complete the integrity of our description. Although it is difficult to describe the head of a right whale without the | ||||||||||

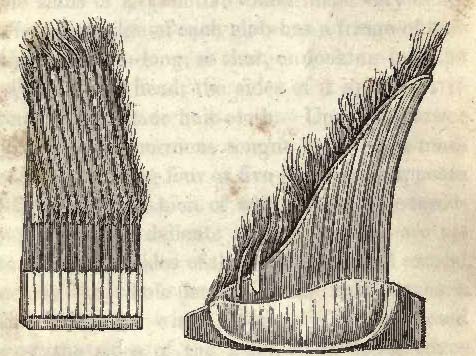

assistance of a drawing, yet a tolerably correct idea may be obtained of it, by comparison with known shapes and objects, and by accurate dimensions. It is curiously adapted to the habits of the animal, and is unlike any other head in nature. Its general shape is not unlike a flat-soled, round-toed shoe, the sides being straight, and the widest part, or heel, joining the body. The lower jaw is, say, eight or ten feet wide, where it joins the body, and grows narrower toward the nose, so that when the jaw-bones are cleaned from the flesh they form a bluntly-pointed arch, and are often preserved and used as gateposts; many of them may be seen, about New Bedford and Nantucket, applied to this use. The skull or crown bone (for there is no upper jaw) is a single bone, rounded on its roof or top, about four or five feet wide at the neck, and gradually lessening to the nostrils or blow-holes, which are at its outward extremity. To this bone is attached the whalebone of commerce, which is in slabs averaging about a quarter of an inch thick. The longest are nearest the body, and are eight or ten inches wide where they join the skull, and are in a large whale six | |||||||||

Perpendicular View of the Whalebone. Side View of the Whalebone.

Perpendicular View of the Whalebone. Side View of the Whalebone.

|

or eight feet long, narrowing to a point as they approach the lower jaw. They hang perpendicularly from the crown to the jaw, with their thickest edges out; they are set about half an inch apart, something like the slabs of a Venetian blind made very close. The inner edge of each slab has a fringe of hair about an inch long, so that, on looking into the cavity of the head, the sides of it appear as if lined with felt or hair-cloth. Upon the lower jaw lies the enormous tongue, which is a mass of fat containing four or five barrels: it appears like a large cushion of white satin, so exceedingly soft and delicate is it. The lips are attached to the sides of the lower jaw, and extend nearly the whole length of the head on each side. Except when feeding, they are closed over the sides of the head, their upper edges fitting to the skull or crown, and the whole head appears as a solid mass; but when it takes its food, the whale unfolds the lips, and they drop upon the surface of the water. The food of this whale, as we have already observed, is a species of shrimp, of a blood-red color. Some of them are very minute, and few are found more than half an inch long; | |||||||||

these float in immense shoals on the surface of the ocean, and sometimes color the water for miles. When the whale is disposed to break his fast, he rushes through a field of shrimps with open mouth, until he has received myriads of the little animals; then, with the lips thrown open, the water is forced out between the slabs which I have described, leaving the shrimps attached to the hairy strainer within; by means of the tongue they are collected, and the delicate mouthful is conveyed to his capacious stomach. When "cutting in a whale," as the carcass rolls over by the power of the windlass, the lips, which are composed entirely of hard blubber, are cut off and hoisted on board as they present themselves. The crown bone is also disjointed from the body, and is hoisted in with the whalebone attached to it. A very large head produces a thousand pounds. The tongue and the fins are also saved; so that when the carcass is turned adrift, after being properly stripped, very little oily matter falls to the share of the birds, who make a terrible clamor, however, in quarreling for that little. The "blubber-room" is a space under the | |||||||||

main hatch, between decks, capable of receiving the blubber of two or three whales; into this every piece is lowered as it comes from the whale: these are called "blanket pieces," and some of them weigh one or two tons. As they are piled one on another, the pressure of their own weight, with the motion of the ship, which is never at rest, causes the oil soon to exude, and, mixing with the blood, more or less of which comes in with each piece, the blubber-room soon presents an indescribable mess. Into this odorous retreat it is the duty of one man immediately to descend with a cuttingspade, to commence cutting the "blanket pieces" into "horse pieces;" these are about a foot square, and by means of a pike or fork, are pitched up on deck for mincing, and taken to the "mincing horse," a small table secured to the rail of the ship, where a boy, with a shorthandled hook, holds the piece to keep it from sliding, while the mincer, with a two-handled knife, slashes it nearly through into thin slices, which just hang together; the piece then becomes a "book," and is pitched into a large tub ready for boiling. A fire is now kindled in the arches under the | |||||||||

pots, which are two or three in number, firmly set in brick work, and each will contain a hogshead of oil. A small quantity of oil is first put in each, and, soon as it becomes heated, fresh. blubber is added, until the pots are full, when a portion from each is bailed out with a large ladle into a copper cooler, from whence it is received into casks and stowed below. The operation of boiling continues day and night until the whole is finished, and sometimes, when whales are plenty, the fires are not put out until the ship is filled. With such an intense fire over a wooden deck and frame for weeks together, and with tarred cordage and canvass above, both of which would burn like tinder, it may seem strange that so few ships take fire. Close attention and untiring vigilance can alone prevent it. If the "pen" under the works, which should be kept full of water, happen to spring aleak in the night without being observed, a short time only would be sufficient to envelop the ship in flames. Sometimes, too, a pot full of boiling oil will burst, without any apparent cause, and let its contents into the fire beneath. Several ships have been lost by such an accident. | ||||||||||||

Frequently the oil in a pot rises at once and boils over, communicating fire to the others: this is generally checked by means of covers which are at hand to smother the flame; but, though not an uncommon occurrence, it is attended with considerable danger. The color of the oil depends much upon the mode of boiling it. Unless the pots are kept perfectly clean, and no sediment permitted to adhere to the bottom, the oil will be dark and of inferior value. It is necessary, therefore, that one man be constantly employed in stirring the mass, while it is the duty of another to skim out the scraps as fast as they are "done:" these are used for fuel, no wood being necessary after the fire is started. The blubber on a fat whale is sometimes, in its thickest parts, from fifteen to twenty inches thick, though seldom more than a foot; it is of a coarser texture and much harder than fat pork. So very full of oil is it, that a cask closely packed with the clean raw fat of the whale will not contain the oil boiled from it, and the scraps are left beside: this has been frequently proved by experiment. Both the sperm and right whale are usually | ||||||||||||

of a jet black color, but not unfrequently the right whale is found with irregular spots of a milky whiteness, very like those on a pied horse. The skin of both kinds is similar. Outside of the sensible skin, which has no peculiarity, there is a coat of something resembling fur, very close and compact, and the fibres united by a glutinous matter, so as to render it about as hard as the rind of a new cheese: this is termed the "black skin," and is about half an inch thick. Still outside of this is a very thin and delicate skin, which, when first detached from the body, whence it is easily stripped, very nearly resembles a glossy black silk; and when the whale basks in the sunbeams on the surface of the water, its smooth outer covering glistens as if it were from the looms of France or Italy, so much is it like the shining silk. Soon as the business of the voyage is fairly commenced by taking the first whale, the appearance of the ship and her crew wofully changes for the worse. The decks, which have hitherto been kept scrupulously clean, are now covered with oil, and it is only by keeping a thick coat of sand scattered over them that the crew are enabled to get about without slipping. | |||||||||

The smoke from the try-works blackens every face, so that the watch on deck resembles a party of colliers. Each rope, too, exposed to its influence, is coated with lamp-black, and the clothing of the men saturated with oil. Even the sails, which on the passage were of a snowy whiteness, receive their share of defilement; for, as they are handed every night, the men, as they spring aloft from the try-works with besmeared hands and clothes, can not furl them without leaving a mark wherever they touch. Your ship, perhaps, has been thoroughly scrubbed and cleansed, crew cleared of "gurry," and all again is ship-shape and tidy, when, just after dinner, as all hands are on deck, the welcome cry is raised, "There she blows!" "Where away?" says the captain, hailing the man aloft. "About two points on the lee bow, sir." There she blows! There she blows! is shouted again, and echoed back by a dozen voices all agog. The mate, if lively, is soon aloft. "What do you make them, Mr. ____?" says the captain, mounted on a thwart in the quarter boat, and scanning the horizon with the most eager interest. "I can't make'em out | |||||||||

yet, sir. There's three or four of'em; and they're going quick to windward." Presently there sings out one from the foretop-gallant yard, "There goes flu-u-u-kesflukes." This is always decisive, for the right whale, after breathing or blowing a few moments on the surface, pitches down head foremost into the deep, and as the head descends, the tail or flukes rise with a graceful curve above the water, and for a moment are seen in nearly a vertical position, and then slowly disappear. All now in your ship is eagerness and engrossment in the motions of your game, and every man is intent at his station. The tubs of lines have just been put into the boat; the harpoons and lances adjusted in their proper places, ready for action. "Lower away!" at length cries the mate, and every boat is instantly resting on the water, manned by their respective crews. "Give way, my lads!" is the next you hear, and the boats are leaping as if alive toward the point where the whale was last seen. All orders are now given in a low tone; every man is doing his utmost, and the boats are springing over the smooth swells, each striving to be headmost in | |||||||||

|

the chase. "Now we rested, with our oars apeak," says a sailor, narrating an actual scene like this, "for the whales, who had gone down, to break water again. Presently they were up and blowing all around, and very much scattered, being alarmed by the boats, so that it was impossible to get near enough for a dart. But at one time five of the monsters rose close to our boats. The mate motioned us all to be silent, when we could have fastened to one, and the only reason, as we supposed, why he did not, was because he was so frightened. "The whale now ran to the southward, and every boat was in chase as fast as we could spring to our oars. The first mate's boat was headmost in the chase, ours next, and the captain's about half a mile astern. The foremost now came up with and fastened to a large whale. We were soon on the battle ground, and saw him struggling to free himself from the barbed harpoon, which had gone deep into his huge carcass. We pulled upon the monster, and our boat-steerer darted another harpoon into him. "Stern all!" shouted the mate. "Stern all, for your lives!" We steered out of the reach of danger, and peaked our oars. | ||||||||||||

"The whale now ran, and took the line out of the boat with such swiftness that we were obliged to throw water on it to prevent its taking fire by friction around the loggerhead. Then he stopped, and blindly thrashed and rolled about in great agony, so that it seemed madness to approach him. By this time, however, the captain came up and boldly darted another harpoon into his writhing body. The enraged whale raised his head above the water, snapped his horrid jaws together, and in his senseless fury lashed the sea into foam with his flukes. The mate now, in his turn, approached near enough to bury a lance deep in his vitals, and shouted again, at the top of his voice, "Stern all!" A thick stream of blood, instead of water, was soon issuing from his spout-holes. Another lance was buried; he was thrown into dying convulsions, and ran around in a circle; but his flurry was soon over; he turned upon his left side, and floated dead. We gave three hearty cheers, and took him in tow for the ship, which was now about fifteen miles off." This towing of captured whales is no boy's play; although it is one of the pleasantest parts of a whaleman's duty, it is also often the most | ||||||||||||

laborious, and fraught, too, with danger when the ship is distant and nightfall at hand. Under a fierce equatorial sun, to row for hours, perhaps right to windward or in a dead calm, with a carcass of seventy tons' weight dragging astern, will blister the hands and strain the muscles of the hardiest whaleman, and wearied nature will sometimes give out. But it is cheerfully endured for the end in view, of cutting in, and trying out, and stowing down a "hundred barreler," that will net to the ship three thousand or fifteen hundred dollars, according as it is a sperm or a right whale. If money makes the mare go, so does oil the crew of a "blubber hunter," from the green cabinboy to the sable doctor. | |||||||||

CHAPTER VI.DIFFERENT CRUISING GROUNDS AND NORTHWEST WHALING.

It will be readily surmised that none but a genuine son of the sea, a veritable Cape Horner, "homeward bound," in the great South Pacific, could make these characteristio rhymes, and many other rude but expressive ones, which there is not room to transcribe here. The sailor that made them says of himself, in the course of some doggerel staves of autobiography,

Different practised whalemen tell me of | |||||||||