|

Thomas Beale, 1807-1849 |

CONTENTS

|

TOHIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PATRONTOHIS GRACE THE PRESIDENTTO THE RIGHT HONORABLE AND HONORABLE THEVICE PRESIDENTS,THE PROFESSORS, FELLOWS, AND MEMBERSOFTHE ELECTIC SOCIETY OF LONDON,THIS LITTLE WORK,FIRST READ AT A MEETING OF THE SOCIETY, AND SINCE

|

PREFACEOn returning to England, after completing an engagement which occupied upwards of two years, in the South Sea Whale Fishery, I was surprised to find, that, when the knowledge of every useful and interesting subject is so widely diffused, so little should be generally known of the natural history of almost the largest inhabitant of our planet, the great Sperm Whale; in fact, till the appearance of Mr. Huggins' admirable print,* few, with the exception of those immediately engaged in the fishery, had the most distant idea even of its external form. Of its manners and habits, people in general seem to know as little as if the capture of this valuable animal had never given employment to British capital, or encouragement to the daring courage of our hardy seamen. The very term, whale-fishery, seems associated with the coast of Greenland or ice-bound Spitzbergen, and the stern magnificance of Arctic scenery; few connect the pursuit of this "sea beast" with the smiling latitudes of the South Pacific, and the Coral Islands of the Torrid Zone; and fewer still have more distinct conception of the object of this pursuit, than that it is a whale, producing the substance called Spermaceti, and the animal oil, best adapted to the purpose of illumination. The Greenland Whale has so frequently been described in a popular manner, that the public voice has long enthroned him as monarch of * Mr. Huggins' truly beautiful print, which was published by that gentleman about six months ago, is the only one ever produced in this country, which gives a correct representation of the Sperm Whale. It not only does that, but also gives a faithful sketch of the form of the boats, number and actions of the crew, with a correct view of the mode by which that animal is destroyed by the lance. By Mr. Huggins' kindness the author was allowed to take a copy of that interesting engraving, and he presents the readers of this little work with it in Plate 1. |

the deep, and perhaps the dread of disturbing such weighty matters as a settled sovereignty, and public opinion, may have deterred those best acquainted with the merits of the case from supporting the more legitimate claims of his southern rival to this pre-eminence. That one so little qualified, as I feel myself to be, should step forward to direct public attention to this subject, requires something in the form of an apology; I can only say, that, had I found any other person willing to adventure his fate in print, the observations, on the peculiarities of the Sperm Whale, which I had made, should have been very much at his service. Never having, whilst engaged in the fishery, contemplated publishing my remarks, the substance of the following pages is chiefly extracted from a log book, in which, for the sole purpose of amusing myself, I noted, daily, the most interesting objects presented to my notice in the course of the voyage. In February last, a paper of mine, on the respiration of this whale, was read at a meeting of the Eclectic Society of London; several of my friends, probably passing a too partial judgement on that paper, advised me to throw together the whole of my observations on the natural history of the animal, with a view to publication. In following this suggestion, I hold myself responsible for every fact stated, except where I give my authority, so that through the quantity of information is much more limited than the importance of the subject demands, still so far as it goes it may be depended upon. Should my humble attempt have the effect of stimulating some person better qualified for the task, to give the Sperm Whale the station which he should hold in the history of animated nature, my object will be fully accomplished. T.B.

3, Philpot-street, London |

named from its having a prominent ridge, or spine, on its back. This whale is probably the longest of the animal creation; but in proportion to its size, and the difficulty of killing it, its value in oil and whalebone is far less considerable than that of the preceding, and on that account it is not sought after by whalers, and not always attacked when met with: it length is about 100 feet -- circumference, 30 to 35 feet. 3. Balaena Musculus -- Broad-nosed Whale -- in many respects much resembling the preceding, from which it differs principally in never attaining so gigantic a size: its length being from 50 to 80 feet. 4. Balaena Boop -- Finner -- generally about 46 feet in length, and very slender. 5. Balaena Rostrata -- Beaked Whale -- the smallest of the whales, length about 25 feet. 6. The Physeter Macrocephalus, or Sperm Whale, which in length comes next to the Balaena Physalis, and in bulk, probably, generally exceeds it, and in commercial value, perhaps, equals the Balaena Mysticetus; for although it does not possess the valuable whalebone of this animal, it furnishes us with the beautiful substance Spermaceti, and is rich in abundance of the finest oil: it is also the source of the perfume termed ambergris: its length is about 80 feet -- circumference about 30 or 35. Of the above enumerated animals, the observations in the few following pages refer mostly to the last: -- |

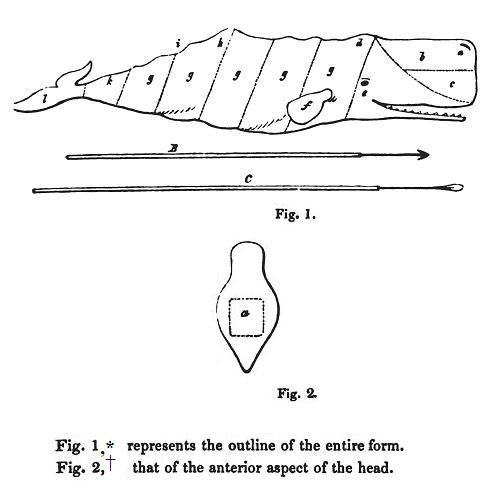

§2. Before proceeding to the account of the habits of the Sperm Whale, I have thought that it might be interesting to prefix a short description of its external form, and some anatomical points in its conformation. By reference to the prefixed engravings, the following description will be much more readily understood: --

Fig. 1.* a, the nostril or spout hole -- b, the situation of the case, c, the junk -- d, the bunch of the neck -- e, the eye -- f, the fin -- g, the spiral strips or blanket pieces -- h, the hump -- i, the ridge-- k, the small -- l, the tail or flukes -- B, a harpoon -- C, a lance. Fig. 2† a, the lines forming the square are intended to represent the flat anterior part of the head. |

The head of the Sperm Whale presents in front, a very thick blunt extremity, called the snout or nose, and constitutes about one-third of the whole length of the animal; at its junction with the body is a large protuberance on the back, called by the whalers the "Bunch of the neck;" immediately behind this, or at what might be termed the shoulder, is the thickest part of the body, which from this point gradually tapers off to the tail, but it does not become much smaller for about another third of the whole length, when the "Small," as it is called, or tail commences; and at this point also, on the back, is a large prominence, of a pyramidal form, called the "Hump," from which a series of smaller processes run half way down the "Small," or tail, constituting what is called the ridge. The body then contracts so much, as to become finally not thicker than the body of a man, and terminates by becoming expanded on the sides into the "Flukes," or tail properly speaking. The two "Flukes" constitute a large triangular fin, resembling, in some respects the tail of fishes, but differing in being placed horizontally; there is a slight notch, or depression, between the flukes posteriorly: they are about 6 or 8 feet in length, and from 12 to 14 in breadth. The chest and belly are narrower than the broadest part of the back, and taper off evenly and beautifully towards the tail, giving what by sailors is termed a |

clear run; the depth of the head and body is in all parts, except the tail, greater than the width. The head viewed in front, as in Fig.2, presents a broad, somewhat flattened surface, rounded and contracted above, considerably expanded on the sides, and gradually contracted below, so as in some degree to attain a resemblance to the cutwater of a ship. At the angle formed by the anterior and superior surfaces on the left side, is placed the single blowing-hole, or nostril, which in the dead animal presents the appearance of a slit or fissure, in form resembling as S, extending longitudinally, and about 12 inches in length. This nostril, however, is surrounded by several muscles, which in the living state, are for the purpose of modifying its shape and dimensions according to the necessities of respiration, similar to those which act upon the nostrils of land animals. In the right side of the nose and head is a large, almost triangular-shaped cavity, called by whalers the "case," which is lined with a beautiful glistening membrane, and covered by a thick layer of muscular fibres and small tendons running in various directions, and finally united by common integuments. This cavity is for the purpose of secreting and containing an oily fluid, which, after death, concretes into a granulated substance of a yellowish colour, the Spermaceti. The size of the case may be estimated, when it is stated that in a large whale it not unfrequently contains |

upward of a ton, or more than ten large barrels of Spermaceti. Beneath the case and nostril, and projecting beyond the lower jaw, is a thick mass of elastic substance called the "Junk:" it is formed of a dense cellular tissue, strenthened by numerous strong tendinous fibres, and infiltrated with very fine sperm oil and Spermaceti. The enormous mouth extends nearly the whole length of the head; both the jaws, but especially the lower, are in front contracted to a very narrow point; and, when the mouth is closed, the lower jaw is received within a sort of cartilaginous lip or projection of the upper one, but principally in front; for further back, at the sides and towards the angle of the mouth, both jaws are furnished with tolerably well developed lips. In the lower jaw are forty-two teeth of a formidable size and conical shape, but none in the upper, which instead presents depressions corresponding to, and for the reception of the crowns of those in the lower jaw. The tongue is small and does not appear to possess the power of very extended motion. The throat is capacious enough to give passage to the body of a man, in this respect presenting a strong contrast with the contracted gullet of the Greenland Whale. The mouth is lined throughout with a pearly white membrane, which becomes continuous at the lips, and borders with the common integuments. |

The eyes are small in comparison with the size of the animal, and are furnished with eyelids, the lower of which is the more moveable; they are placed immediately above the angle of the mouth, at the widest part of the head. At a short distance behind the eyes are the external openings of the ears, of size sufficient to admit a small quill, and unprovided with any external auricular appendage. Behind, and not far from the posterior termination of the mouth, are placed the swimming paws, or fins, which are analogous in formation to the anterior extremities of other animals, or the arms of man: they are not used as instruments of progression, but probably in giving a direction to that motion, in balancing the body in sinking suddenly, and occasionally in supporting their young. §3. In a full-grown male Sperm Whale, of the largest size, or about 80 feet, the dimensions may be given as follow: -- Depth of head from 8 to 9 feet -- breadth of ditto from 5 to 6 feet -- depth of body seldom exceeds 12 or 14 feet, so that the circumference of the largest Sperm Whale, of 80 feet, will seldom exceed 30 or 35 feet, which is not more than that of a Greenland Whale measuring only 50 or 60 feet in length, according to the measurements given by Mr. Scoresby. |

The swimming paws or fins are about 3 feet long, and 2 broad; the dimensions of the flukes or tail have been previously mentioned. §4. In reviewing this description of the external form, and some of the organs of the Sperm Whale, it will perhaps not be uninteresting if some comparison is instituted between them and the corresponding points of the Greenland Whale; in doing this, the remarkable adapation of form and parts to different habits, situation, and food, will not fail to strike every one with admiration. But I shall not enter entirely into many of these considerations until I describe the habits of feeding, and breathing of the Sperm Whale. A peculiarity of the Sperm Whale, which strikes at first sight every beholder, is the apparently disproportionate and unwieldly bulk of the head; but this peculiarity, instead of being, as might be supposed, an impediment to the freedom of the animal's motion, in his native element, is, in fact, on the contrary in some respects, very conducive to his lightness and agility, if such a term can with propriety be applied to such an enormous creature; for a great part of the bulk of the head is made up of a large thin membranous case, containing, during life, a thin oil of much less specific gravity than water; below which again is the junk, which, although heavier than the Spermaceti, is still |

lighter than the element in which the whale moves; consequently the head taken as a whole, is lighter specifically than any other part of the body and will always have a tendency to rise, at least, so far above the surface as to elevate the nostril, or "blow-hole," sufficiently for all purposes of respiration; and more than this, a very slight effort on the part of the fish would only be necessary to raise the whole of the anterior flat surface of the nose out of the water; in case the animal should wish to increase his speed to the utmost, the narrow inferior surface, which has been before stated to bear some resemblance to the cutwater of a ship, and which would in fact answer the same purpose to the whale, would be the only part exposed to the pressure of the water in front, enabling him thus to pass with the greatest celerity and ease through the boundless tracks of his wide domain. It is in this shape of the head that the Sperm Whale differs in the most remarkable degree from the Greenland Whale, the shape of whose head more resembles that of the porpoise, and in it the nostril is situated much farther back, rendering it seldom or ever necessary for the nose to be elevated above the surface of the water; and when swimming even at the greatest speed, the Greenland Whale keeps nearly the whole of the head under it, but as his head tapers off evenly in front; this circumstance does not much impede his motion, the rate of which is, however, never equal to |

that of a Sperm Whale. It seems, indeed, in point of fact, that this purpose of rendering the head of light specific gravity, is the only use of this mass of oil and fat, although many have supposed, and not without some degree of probability, that the "Junk" especially may be serviceable in obviating the injurious effects of concussion, should the whale happen to meet with any obstacle when in full career; this supposition, however, would appear hardly tenable, when we consider the Greenland Whale, although living among the rock-like icebergs of the Arctic Seas, has no such convenient provision, and with senses probably in all, and certainly in one respect less acute that those of the Sperm Whale, on which account it would seem requisite for him to possess this defence rather than the Sperm Whale, whose habitation is, for the most part, in the smiling latitude of the Southern Seas. Considering the habits and mode of feeding, and the superior activity and apparent intelligence of the Sperm Whale, we shall be prepared to expect that he must possess a corresponding superiority in his external senses, and we accordingly find, that he enjoys a more perfect organ of hearing, in having an external opening of considerable size for the purpose of conveying sounds to the internal ear, more readily and acutely than could be done through the dense and thick integument, which is continued over the auricular opening in the Northern Whale. |

Although the eyes in both animals are very small in comparison with their bulk, yet it is remarked that they are tolerably quick-sighted. I am not aware that the Sperm Whale possesses in this respect any superiority. Passing to the mouth, we again observe a very remarkable difference in the conformation of the two animals, as in place of the enormous plates of whalebone, which are found attached to the upper jaw of the Greenland Whale, we in the Sperm Whale find only depressions for the reception of the teeth of the lower jaw, organs, which again are totally wanting in the other, corresponding with these distinctions which plainly point out that the food of the two whales must be very different, we find a remarkable difference in the size of the gullet. The several humps and ridges, on the back of the Sperm Whale constitute another difference in their exterenal aspect; these prominences, however, are by no means peculiar to the Sperm Whale, as they are possessed also by several other species of whales, as the Razor-back and Broad-nosed Whales, and some others; and it would seem that the possession of these parts marks those whales which are noted for their swiftness in flight, and their activity in endeavouring to defend themselves when attacked, which may be explained in this way, or it may be considered probable, that these prominences result from a greater |

development, in the situations where they are placed, of those processes of the vertebrae or bones composing the spine, called the spinal processes, and to which the muscles principally used in progression and other motions, are attached, as well as those muscles and ligaments which support the long and bulky head; they consequently must indicate an increase in the size and strength of these muscles and ligaments, &c. and on this account constitute a very remarkable difference between those whales possessed of them, and those not so furnished. This distinction is so great that it induced Lacapéde to divide the genus Balæna into those with a hump, and those without, employing the name Balæna for the latter, and styling the others Balænoptera. I have before adverted to the sharp cutwater-like conformation of the under part of the head in the Sperm Whale, and it is worthy of remark that the same part of the Greenland Whale is nearly, if not altogether, flat. §5. The skin of the Sperm Whale, as of all other cetaceous animals, is without scales, smooth, but occasionally, in old whales, wrinkled, and frequently marked on the sides by linear impressions, appearing as if rubbed against some angular body. The colour of the skin, over the greatest part of its extent, is very dark -- most so on the upper part of the head, the back, and |

on the flukes, in which situation it is in fact sometimes black: on the sides it gradually assumes a lighter tint, till on the breast it becomes silvery grey. In different individuals there is, however, considerable variety of shade, and some are even piebald. Old "Bulls," as full-grown males are called by whalers, have generally a portion of grey on the nose immediately above the fore-part of the upper-jaw, and they are then said to be grey headed. In young whales the skin is about three eighths of an inch thick, but in old ones it is not more than one eighth. Immediately beneath the "black skin" lies the blubber, or fat, which on the breast of a large whale acquires the thickness of 14 inches, and on most other parts of the body it measures from 8 to 11. This covering is called by the South Sea whalers the blanket; it is of a light yellow colour, and when melted down, furnishes the Sperm oil. The blubbler serves two excellent purposes to the whale, in rendering it buoyant, and in furnishing it with a warm protection from the coldness of the surrounding element; in this last respect answering well to the name bestowed upon it by the sailors |

the "Squid," and by naturalists the "Sepia Octopedia;" this at least forms the principal part of his sustenance when at a distance from shore, or what is called "off-shore ground;" but when met with nearer land, he frequently, when mortally or severly wounded, ejects large quantities of small fish, which are met with in great abundance in the bays and near the shore, especially of Japan; he sometimes, however, throws up fish as large as a moderate sized salmon. It would be difficult to believe that so large and unwieldly an animal as this whale could ever catch a sufficient quantity of such small animals, if he had to pursue them individually for his food; and I am not aware that either the fish he sometimes lives upon, or the squid, are ever found in shoals, or closely congregated. It remains, then to be inquired in what way the Sperm Whale usually does supply his enormous body with sufficient food. It appears from all I can learn among the oldest and most experienced whalers, and from the observations I have been enabled to make myself, that when the whale is inclined to feed, he descends a certain depth below the surface of the ocean, and there remains in as quiet a state as possible, opening his enormous mouth until the lower jaw hangs down perpendicularly, or at right angles with the body. The roof of his mouth, the tongue, and especially his teeth, being of a bright glistening white colour, must of course present a |

remarkable appearance, and which seems to be the incitement by which his prey are attracted; and when a sufficient number, I suppose, are within the mouth, he rapidly closes his jaw and swallows the contents: that this is the mode in which he acquires and secures his prey, I am led to believe also, from the following considerations: -- The Sperm Whale is subject to several diseases, one of which is a perfect, or imperfect, loss of sight. A whale, perfectly blind, was taken by Captain W. Swain, now of the Sarah and Elizabeth whaler, of London, both eyes of which were completely disorganized, the orbits being occupied by fungous masses, protruding considerably, rendering it certain that the whale must have been deprived of vision for a long space of time, yet, notwithstanding this, the animal was quite as fat, and produced as much oil, as any other captured of the same size. Besides blindness, the whale is frequently subject to deformity of the lower jaw, two instances of which I have seen myself, in which the deformity was so great as to render it impossible for the animal to find the jaws useful in catching small fish, or even one might have supposed in deglutition; yet these whales possessed as much blubber and were as rich in oil as any of a similar size I have seen before or since. In both these instances of crooked jaws, the nutrition of the animal appeared to be equally perfect, but the deformities were different; in one case the jaw |

being bent to the right side, and rolled as it were like a scroll; in the other it was bent downwards, but also curved upon itself. It would be interesting here to inquire into the causes of this deformity, but whether it is the effect of disease, or the consequences of accident, I am unable positively to determine. Old whalers affirm that it is caused by fighting; they state that the Sperm Whale fights, by rushing head first, one upon the other, their mouths at the same time wide open, their object appearing to be the seizing of their opponent by the lower jaw, for which purpose they frequently turn themselves on the side; in this posture they strive vehemently for the mastery; I have never had the good fortune to witness one of these combats, but if it be the fact that such take place, (of which I have little doubt,) we need not wonder at seeing so many deformed jaws in this kind of whale, for we can easily suppose the enormous force exerted on these occasions, taking into consideration, at the same time, the comparative slenderness of the jaw-bone in this animal. Some corroboration of the above statements arises from the fact, as far as my knowledge extends, that the female is seldom or never seen affected with this deformity. From these facts it may almost be deduced, or at |

least surmised with a great degree of probability, that the mode of procuring food as above stated, as that pursued by the Sperm Whale, is the true one: for without eyes, and with a jaw (his only instrument of prehension) so much deformed, the animal would seem incapable of pursuing his prey, and would consequently gain but a very precarious subsistence, if its food did not actually throng about the mouth and throat, invited by their appearance, and attracted also, as some suppose, by the peculiar and very strong odour of the Sperm Whale. It is well known, that many kinds of fish are attracted by substances possessing a white dazzling appearance, for not only the hungry shark, but the cautious and active dolphin both occasionally fall victims to this partiality, as I have had many opportunities of observing. When the Kent South Sea whaler was fishing on the "off-shore ground of Peru," the crew caught a great number of the Sepia Octopedia, or Squid, (the peculiar food of the Sperm Whale,) in one night, by merely lowering a piece of polished lead armed with fish-hooks, a certain depth into the sea. The Sepia gathered around it instantly, so that by giving a slight jerk to the line, the hooks were easily driven into their bodies. The teeth of the Sperm Whale are merely organs of prehension, they can be of no use for mastication, and, consequently we find that the fish, &c. which he |

occasionally vomits, present no marks of having undergone that process. The manner of the young ones sucking is a matter involved in some obscurity. It is impossible, from the curious conformation of the mouth, that the young one could seize the nipple of the mother, with the fore part of it, for there are no soft lips at this part; but instead, the jaws are edged with a smooth and very hard cartilaginous substance; but about two feet from the angle of the mouth they begin to be furnished with something like lips, which form at the angle some loose folds, soft and elastic, and it is commonly believed by the most intelligent whalers, that it is by this part the young whale seizes the nipple, and performs the act of sucking, and which is doubtless the mode of its doing so. § 2. Swimming.Notwithstanding his enormous size we find that the Sperm Whale has the power of moving through the water, with the greatest ease, and with considerable velocity. When undisturbed, he passes tranquilly along just below the surface of the water, at the rate of about three or four miles an hour, which motion he effects by a gentle oblique motion from side to side, of the flukes, precisely in the same manner as a boat is skulled by means of an oar over the stern. When |

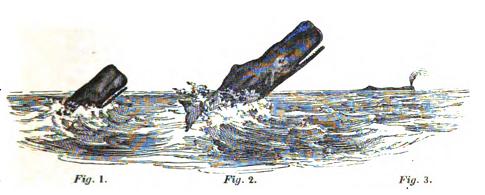

proceeding at this his common rate, his body lies horizontally, his hump projecting above the surface (see Plate No. 2)) with the water a little disturbed around it, and more or less so according to his velocity; this disturbed water is called by whalers "white water," and from the greater or less quantity of it an experienced whaler can judge very accurately of the rate at which the whale is going, from a distance even of four or five miles.

No. 2.

In this mode of swimming, the whale is able to attain a velocity of about seven miles an hour, but when desirous of proceeding at a greater rate the action of the tail is materially altered; instead of being moved laterally and obliquely, it strikes the water with the broad flat surface of the flukes in a direct manner, upwards and downwards; and each time the blow is made with the inferior surface, the head of the whale sinks down to the depth of eight or ten feet, but when the blow is reversed, it rises out of the water, presenting then to it only the sharp cutwater-like inferior portion. |

The blow with the upper surface of the flukes appears to be by far the most powerful, and as, at the same time, the resistance of the broad anterior surface of the head is removed, appears to be the principal means of progression. This mode of swimming, with the head alternately in and out of the water, is called by sailors, "going head out," (see Plate No. 2,) and in this way the whale can attain a speed of ten or twelve miles an hour, and this latter I believe to be his greatest velocity. The tail is thus seen to be the great means of progression, and the fins are not much used for that purpose, but occasionally when suddenly disturbed, the whale sinks quickly and directly downwards in the horizontal position, which he effects by strking upwards with the fins and tail. § 3. Breathing.All the cetacea, as is well known, are warm-blooded animals, and possess lungs, and a corresponding respiratory apparatus resembling those of terrestrial animals, and require consequently a frequent intercourse with atmospheric air, and for this purpose it is of course necessary that they should rise to the surface of the water at certain intervals. The majority of this class of animals do not appear to perform this function with any regularity, and it is in this respect that the Sperm Whale is remarkably distinguished among his congeners, and it is from his |

peculiar mode of blowing that he is recognised, even from a great distance, by the most inexperienced whaler. When at the surface of the ocean for the purpose of respiration, the whale generally remains still, but occasionally continues making a gentle progress during the whole of his breathing time. If the water is moderately smooth, the first part of the whale observable is a dark-coloured pyramidal mass, projecting about two or three feet above the surface, which is the "Hump." At very regular intervals of time, the nose, or snout, emerges at a distance of from forty to fifty feet from the hump in the full-grown male; from the extremity of the nose the spout is thrown up, which, when seen from a distance, appears thick, low, and bushy, and of a white colour; this is formed by the air expired forcibly by the animal, through the blow-hole, acquiring its white colour from minute particles of water, previously lodged in the chink, or fissure of the nostril. The spout is projected from the blow hole, at an angle of 135 degrees, in a slow and continuous manner for the space of about three seconds of time.* If the weather is fine and clear, and there is a gentle breeze at the time, it may be seen from the mast head * The whale represented as breathing, in Plate No. 2, was intended to shew the form and direction of the spout, but the engraver, as will be seen, has made it nearly perpendicular, a mistake which could not be very well rectified without going to the expense of a new cut. |

of a moderate sized vessel at the distance of four or five miles. The spout of the Sperm Whale differs much from that of other large cetacea, in which it is double, and projected thin, and like a sudden jet, and as in these animals the blow holes are situated nearly on the top of the head, it is thrown up to a considerable height, in almost a perpendicular direction. When, however, a Sperm Whale is alarmed or "gallied," the spout is thrown up much higher and with great rapidity, and consequently differs much from its usual appearance. The regularity with which every action connected with its breathing is performed by the Sperm Whale, is very remarkable. The length of time he remains at the surface, the number of spouts or expirations made at one time, the intervals between the spouts, the time he remains invisible "in the depths of the ocean buried," are all, when the animal is undisturbed, as regular in succession and duration as it is possible to imagine. In different individuals the times consumed in performing these several acts vary, but in each they are minutely regular, and this well-known regularity is of considerable use to the fishers, for when a whaler has once noticed the periods of any particular Sperm Whale, and which is not alarmed, he knows to a minute when to expect it again at the surface, and how long it will remain there. |

Immediately after each spout, the nose sinks beneath the water, scarecly a second intervening for the act of inspiration, which must consequently be performed very quickly, the air rushing into the chest with an astonishing velocity -- there is, however, no sound caused by the inspiration, and very little by the expiration, or spout. In a large "Bull" the time consumed in making one inspiration and one expiration, or the space from the termination of one spout to that of another, is ten seconds; during six of which, the nostril is beneath the surface of the water, the inspiration occupying one, and the expiration three seconds, and at each breathing time the whale makes from sixty to seventy expirations, and remains, therefore, at the surface ten or eleven minutes. At the termination of this breathing time, or as whalers say, when he has had his "spoutings out," the head sinks slowly, the "Small," or the part between the "Hump" and "Flukes," appears above the water, curved, with the convexity upwards; the flukes are then lifted high into the air, and the animal, having assumed a straight position, descends perpendicularly to an unknown depth. This act is performed with the greatest regularity and slowness. The whale continues thus hidden beneath the surface for an hour and ten minutes; some will remain an hour and ten minutes; some will remain an hour and twenty minutes, and sometimes for only one |

hour, but there are rare exceptions. If we then take into consideration the quantity of time that the full-grown Sperm Whale consumes in respiration, and also the time he takes in searching for food, and performing other acts below the surface, we shall find, by a trifling calculation, that the former bears proportion to the latter, as one to seven, or in other words, that a seventh of the time of this huge animal is consumed in the function of respiration. The females being found generally in large numbers and in close company, it is difficult to fix the attention upon one individual, so as to ascertain precisely the time consumed below the surface; however, as all in one flock generally rise at the same time, it may be observed, that they remain below the water about twenty minutes; they make about thirty-five or forty expirations during the period they are at the surface, which is about four minutes, and they thus consume about a fifth of their time in respiration, a proportion considerably greater than that of the adult males. The same circumstances of accelerated respiration are observable also in young whales, and the acceleration seems to bear a certain definite proportion, with their respective ages and size. When disturbed or alarmed, this regularity in breathing appears to be no longer observed. For instance, when a "Bull," which when undisturbed remains at the surface until he has made sixty expirations, is |

alarmed by the approach of a boat, it immediately plunges beneath the waves, although it may probably have performed half its usual number, but will soon rise again not far distant, and finish his full number of respirations, and in this case generally also, he sinks without having assumed the perpendicular position before described; on the contrary, he sinks suddenly in the horizontal position, and with remarkable rapidity, leaving a sort of vortex, or whirlpool, in the place where his huge body lately floated. This curious movement is effected, as has been before stated, by some powerful upward strokes of the swimming paws and flukes. When urging his rapid course through the ocean, in that mode of swimming which is called going "Head out," the spout is thrown up every time the head is raised above the surface, and under these circumstances of violent muscular exertion, as would be expected, the respiration is altogether much more hurried than usual. § 4. When in a state of alarm, or gambolling in sport on the surface of the ocean, the Sperm Whale has many curious modes of acting, with the reason of some, I am at present unacquainted. It is difficult to conceive any object in nature calculated to cause alarm to this leviathan; he appears however to be remarkably timid, and is readily |

alarmed by the approach of a whale boat. When seriously alarmed, the whale is said by sailors to be "gallied," or probably more properly galled, and in this state he performs many actions very differently from his usual mode, as has been mentioned in speaking of his swimming and breathing; and many also which he is never observed to perform under any other circumstances -- one of them is what is called "Sweeping," which consists in moving the tail slowly, from side to side, on the surface of the water, as if feeling for the boat, or any other object that may be in the neighbourhood. The whale has also an extraordinary manner of rolling over and over, on the surface, and this he does especially when "fastened to," which means, when a harpoon, with a line attached, is fixed in his body; and in this case they will sometimes coil an amazing length of line around them. They sometimes also place themselves in a perpendicular posture, with the head only above water, presenting in this position a most extraordinary appearance when seen from a distance, resembling large black rocks in the midst of the ocean: this posture they seem to assume for the purpose of surveying more perfectly, or more easily, the surrounding expanse. A species of whale, called by whalers "Black Fish," is most frequently in the habit of assuming this position. |

The eyes of the Sperm Whale being placed in the widest part of the head, of course afford the animal an external field of vision, and he appars to view objects very readily that are placed laterally in a direct line with the eye, when they are placed at some distance before him: his common manner of looking at a boat, or ship, is to turn over on his side, so as to cause the rays from the object to strike directly upon the retina. Now when alarmed, and consequently anxious to take as rapid a glance as possible on all sides, he can much more readily do so when in the above described perpendicular posture, and this consequently appears to be the reason of his assuming it. One of the most curious and surprising of the actions of the Sperm Whale, is that of leaping completely out of the water, or of "Breaching" as it is called by whalers, (see Plate No. 2.) The way in which he performs this extraordinary motion, appears to be by descending to a certain depth below the surface, and then making some powerful strokes with his tail, which are frequently and rapidly repeated, and thus convey a great degree of velocity to his body before it reaches the surface, when he darts completely out. The inclination his body forms with the surface, when just emerged and at his greatest elevation, forms an angle of about 45 degrees, the flukes lying parallel with the surface: in falling, the animal rolls his body slightly, so that he always falls |

on his side; he seldom breaches more than twice or thrice at a time, or in quick succession. The breach of a whale may be seen from the mast head on a clear day at a distance of six miles. Occasionally when lying at the surface, the whale appears to amuse itself by violently beating the water with its tail; this act is called "Lob Tailing," and the water lashed in this way into foam, is termed "white water" by the whaler, and by which he is recognized from a great distance. § 5. The sperm whale is a gregarious animal, and the herds formed by it are of two kinds, the one consisting of females, the other of young not fully grown males, and the latter are again generally subdivided into groups, according to their ages. These herds are called by whalers "Schools," and occasionally, consist of great numbers: I have seen in one school as man as five or six hundred. With each herd or school of females, are always several large "Bulls," the lords of the herd, or as they are called, the schoolmasters. These males are extremely jealous of intrusion by strangers, and fight fiercely to maintain their rights. The full grown male whales, or "large whales," almost always go alone in search of food, and when they are seen in company they are supposed to be making passages or migrating from one feeding ground to another. |

The large whale is generally very incautious, and, if alone he is without difficulty attacked, and, generally, very easily killed; as he frequently, after receiving the first blow or plunge of the harpoon, appears hardly to feel it, but continues lying like a , log of wood in the water, before he rallies or makes any attempt to escape from his enemies. "Large whales" are however sometimes, but rarely, met with, remarkably cunning and full of courage, when they will commit dreadful havoc with their jaws and tail; the jaw and head, however, appear to be their principal offensive weapons. The female breeds at all seasons, producing one at a time; her time of gestation is unknown, but is supposed to be not very long. She is much smaller than the male, in proportion, of nearly one to four or five. They are very remarkable for their strong feeling of sociality or attachment to one another, and this is carried to so great an extent, as that one female of a herd being attacked and wounded, her faithful companions will remain around her to the last moment, or until they are wounded themselves. This act of remaining by a wounded companion is called by whalers "heaving to," and whole "Schools" |

have been destroyed by dexterous management, when several ships have been in company, wholly from these whales possessing this remarkable disposition. The attachment appears to be reciprocal on the part of the young whales, which have been seen about the ship for hours after their parent has been killed. The young males, or "young Bulls," also generally go in large "Schools," but differ remarkably from the females in disposition, inasmuch as they make an immediate and rapid retreat upon one of their number being struck, who is left to take the best care he can of himself. I never but once saw them "heave to," and in that case it was only for a short space of time. They are also very cunning and cautious, keeping at all times a good look out for danger. It is consequently necessary for the whaler to be extremely cautious in his mode of approaching them, so as if possible to escape being seen or heard; for they have some mode of communicating one with another through a whole "School,", in an incredibily short space of time. "Young Bulls" are consequently much more troublesome to attack, and more difficult and dangerous to kill, than when full grown, great dexterity and despatch being necessary to give them no time to recover from the pain and fright caused by the first blow. When about three-fourths grown, or sometimes only |

half, they separate from each other, and go singly in search of food. All sperm whales, both large and small, have some method of communicating by signals to each other, by which they become apprised of the near approach of danger; and this they do, although the distance may be very considerable between them, sometimes amounting to four, five, or even seven miles. The mode by which this is effected, remains a curious secret. This species of whale is never, or very rarely, seen on soundings; it inhabits the blue unfathomable ocean; far away from land it seeks its prey, produces its young, and follows all its natural inclinations. At times it approaches the shore, but only to within a certain distance, and where the water is still unfathomable. CHAPTER III.Of the modes of "pursuing," "killing," and "cutting in " the Sperm Whale -- with an account of its places of resort.

§1. It will not be uninteresting here to premise a short account of the rise and progress of the South Sea, or Sperm Whale Fishery, from its first institution to the present day. This account, together with that of the number of ships up to the year 1830 engaged in |

the fishery, are obtained from the valuable Dictionary of Commerce, of Mr. M'Culloch. "The South Sea Fishery was not prosecuted by the English till about the beginning of the American war, and as the Americans had already entered on it with vigour and success, four American harpooners were sent out in each vessel. In 1791, 75 whale ships were sent to the South Sea; but the number has not been so great since. In 1830 only 31 ships were sent out, of the burthen 10,997 tons, and carrying 937 men. The Macrocephalus, or Spermaceti Whale, is particularly abundant in the neighbourhood of the Spice Islands; and Mr. Crawford, in his valuable work on the Eastern Archipelago, (Vol. iii. p.447) has entered into some details to shew that the fishery carried on there is of greater importance than the spice trade. Unluckily, however, the statements on which Mr. Crawford founded his comparisons were entirely erroneous, neither the ships nor the men employed amounting to more than a fifth or sixth part of what he has represented. But errors of this sort abound in the works of those who had better means of coming at the truth. Mr. Barrow, in an article on the fisheries, in the supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, states the number of ships fitted out for the northern whale fishery in 1814 at 143, and their crews at 7150; and he further states the number of ships fitted out for the southern fishery in 1815 at 107, and their crews at 3210. In point of fact, however, only 112 whale ships cleared out for |

the north in 1814, carrying 4708 men; and in 1815, only 22 whale ships cleared out for the south, carrying 529 men! How Mr. Barrow, who has access to official documents, should have given the sanction of his authority to so erroneous an estimate, we know not. In the same article Mr. Barrow estimates the entire annual value of the British fisheries of all sorts, at L8,300,000. But it might be very easily shown that, in rating it at L3,500,000, we should certainly be up to the mark, or rather, perhaps, beyond it. We annex a detailed account of the progress of the Southern Whale Fishery since 1814. An account of the number of ships annually fitted out in Great Britain, with their tonnage and crews, for the Southern Whale Fishery, and of the bounties on their account, from 1814 to 1824, both inclusive.

An account of the number of ships fitted out in the different Ports of Great Britain, (specifying the same,) for the Southern Whale Fishery, their tonnage, and the number of men on board, during the three years ending 5th January, 1830.

Office of Registrar General of Shipping, JOHN COVEY. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"For a lengthened period the Americans have prosecuted the whale fishery, with greater vigour and success than, perhaps, any other people. They commenced it in 1690, and, for about 50 years, found an ample supply of fish on their own shores; but the whale having abandoned them, the American navigators entered, with extraordinary ardour, into the fisheries carried on in the Northern and Southern Oceans. From 1771 to 1775, Massachusetts employed, annually, 183 vessels, carrying 13,820 tons, in the former; and 121 vessels, carrying 14,026 tons, in the latter. Mr. Burke, in his famous speech on American affairs, in 1774, adverted to this wonderful display of daring enterprise, as follows: -- "'As to the wealth,' said he, 'which the colonists have drawn from the sea by their fisheries, you had all that matter fully opened at your bar. You surely thought these acquisitions of value, for they seemed to excite your envy, and yet the spirit by which that enterprising employment has been exercised ought rather, in my opinion, to have raised esteem and admiration. And pray, Sir, what in the world is equal to it? pass by the other parts, and look at the manner in which the New England people carry on the whale fishery. While we follow them among the trembling mountains of ice, and behold them penetrating into the deepest frozen recesses of Hudson's and Davis' Straits; while we are looking for them beneath the |

Arctic Circle, we hear that they have pierced into the opposite region of polar cold; that they are at the antipodes, and engaged under the frozen serpent of the South. Falkland Island, which seems too remote and too romantic an object for the grasp of national ambition, is but a stage and resting place for their victorious industry. Nor is the equinoctial heat more discouraging to them than the accumulated winter of both poles. We learn, that while some of them draw the line or strike the harpoon on the coast of Africa, others run the longitude, and pursue their gigantic game along the coast of Brazil. No sea, but what is vexed with their fisheries. No climate that is not witness of their toils. Neither the perseverance of Holland, nor the activity of France, nor the dexterous and firm sagacity of English enterprise, ever carried this most perilous mode of hardy industry to the extent to which it has been pursued by this recent people; a people who are still in the gristle, and not hardened into manhood.' "The unfortunate war that broke out soon after this speech was delivered, checked for a while the progress of the fishery; but it was resumed with renewed vigour as soon as peace was restored. The American fishery has been principally carried on from Nantucket and New Bedford, in Massachusetts; and for a considerable time past the ships have mostly resorted to the Southern Seas. 'Although,' says Mr. Pitkin, 'Great Britain has, at various times, given large bounties to her ships |

employed in this fishery, yet the whalemen of Nantucket and New Bedford, unprotected and unsupported by any thing but their industry and enterprise, have generally been able to meet their competitors in a foreign market.'" -- Commerce of the United States, 2d. ed. p.46. France, which preceded the other nations of Europe in the whale fishery, can hardly be said, for many years past, to have had any share in it. In 1784, Louis XVI. endeavoured to revive it. With this view he fitted out six ships at Dunkirk, on his own account, which were furnished with harpooners, and a number of experienced seamen brought at a great expense from Nantucket. The adventure was more successful than could have been reasonably expected, considering the auspices under which it was carried on. Several private individuals followed the example of his majesty, and in 1790, France had about 40 ships employed in the fishery. The revolutionary war destroyed every vestige of this rising trade. Since the peace, the government has made great efforts for its renewal, but hitherto without success; and it is singular that, with the exception of an American house established at Dunkirk, hardly any one has thought of sending out a ship. Within these last few years not only has the port of London received vast quantities of Sperm oil, and Spermaceti, but our colony of New South Wales is busily employed in the branch of commerce, and no doubt, with great profit to its merchants, and others |

engaged in the fishery. They are situated so much nearer to the fishing grounds, that neither the time nor the expense of fitting out their ships can be compared with those vessels that are fitted out from England. §2. The ships engaged in this pursuit are generally from 300 to 400 tons burthen, having crews to the number of about 30 men and officers. They sail on their voyage from London at all times of the year, fully provisioned for two and a half or three years. Each vessel carries six whale boats, which, as being the principal means used in the pursuit and capture of the whale, it will be necessary to describe fully. They are of a construction admirably adapted to the purposes for which they are intended, combining great sharpness of form for swiftness of motion, and at the same time considerable buoyancy and stability, to enable them to resist the effects of a sometimes rough and boisterous sea. They are about 27 feet long, by 4 in breadth, sharp at both ends for motion in either direction without the necessity of turning. Near that end which is considered the stern of the boat, is placed a strong upright rounded piece of wood, not exactly in the centre of the boat, called the loggerhead; at the other end by the side of the stern is a groove, through which the harpoon line runs out. |

To each boat are allotted two lines of 200 fathoms and their tubs, which are placed in the bottom of the boat -- three or four harpoons, two or three lances, a keg containing a lantern, tinder-box, and other small articles; two or three small flags, called "Whifts," and one or two "Drouges," which are quadrilateral pieces of board, with a central handle or upright, by which they are attached occasionally to the harpoon line, for the purpose of checking in some degree the speed of the whale in sounding or running.

No. 1

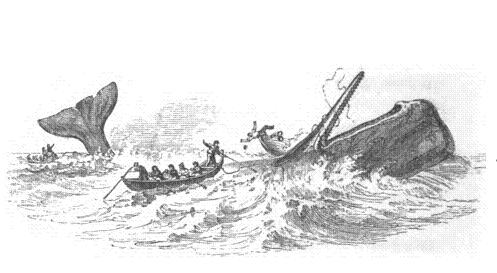

Each boat has a crew of six men, two of whom are called the "Headsman" and "Boatsteerer," (see Plate 1.) Four of these boats are generally used in the chase, and are under the command of the captain and their mates respectively. From the commencement of the voyage, men are placed at each mast head, who are relieved every two hours, one officer is also placed on the fore top gallant |

yard -- consequently there are four persons constantly on the look out from the most elevated parts of the ship. From the commencement of the voyage also all utensils and instruments are got ready, although the ships are frequently out six months without taking a fish. When a whale is seen by any of the look-outs, he calls "there he spouts," and as often as it spouts afterwards, he cries, "there again:" it is impossible to describe the excitement and agitation produced by this welcome intelligence; the listlessness produced by the previous monotony of a long, and perhaps, hitherto profitless voyage, is shaken off among all on board; from the highest to the lowest, all is bustle and activity, some rushing up the shrouds and rigging to observe the number, distance, and position of the whale, or whales; and if near hand, others eagerly leap into the boats, and pull with ardent emulation towards their intended victim. If the whales should be some distance to leeward, endeavour is made to run the ship within a quarter of a mile of them, but if to windward, the boats are sent in chase; an arduous task. From hour to hour, for several successive risings of the whale, sometimes from sun rise to sun set, under the direct rays of a tropical sun, do these hardy men endure the utmost suffering and fatigue, unheeded and almost unfelt, under the eager excitement of the chase, for hope supports their minds. |

The crew of the boat, as has been mentioned, consists of the headsman, boatsteerer, and four hands; of these, the headsman, who has the command of the boat, steers it until the whale is reached and struck with the harpoon. The boatsteerer also at this time pulls the bow oar, but when near the whale he ceases rowing, quits the oar and strikes the harpoon into the animal, the line attached to which runs between the men to the after part of the boat, and after passing two or three times round the loggerhead, is continuous with the coil lying in the bottom of the boat. The boatsteerer now comes aft, and steers the boat by means of an oar passed through a ring attached to the stern called a "Grummet," he also attends the line through all the subsequent operations: the headsman at the same time passes forwards, and takes his station in the bows of the boat, prepared at the proper time to plunge his lance into the body of the whale. It requires considerable tact and experience to do this in the most effectual manner. When in pursuit of the whale in this way with the boats, it occasionally happens that just at the moment the harpoon is about to be thrust into its body, the whale suddenly descends -- its course, however, has been observed, and the boats are placed in a position to be near it when it again rises to breathe; the time, as has |

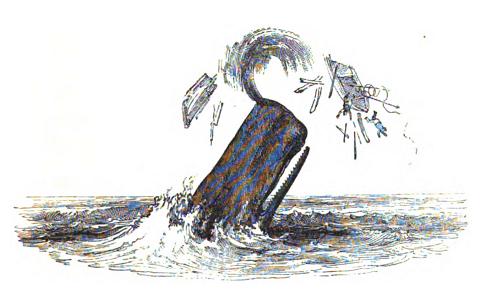

been before stated, when he will do this is known to a minute. §3. When the boat's head is placed against the body of the whale, the headsman begins to destroy it by thrusting his lance into its body, or darting it from a distance. At the moment of lancing, he cries, "stern all," the oars are then immediately backed and the boat's stern becoming its cutwater, it is thus removed from danger without the trouble or loss of time in turning. Upon feeling the lance the whale generally plunges and throws itself in all directions, lashing the water with its tail, and threatening destruction with its formidable jaw. (See Plate No. 1.) After being lanced, females and young bulls make the most violent efforts to escape, and being remarkably quick in their actions, they frequently afford considerable trouble. Those "young bulls" which yield about 40 barrels of oil, and are consequently called by whalers 40 barrel bulls, are perhaps the most difficult to destroy. The larger whales, such yield 80 or more barrels, not being nearly so active, and probably not feeling so acutely, are generally, by expert whalers, easily killed, and with less damage to those employed than the smaller ones. But these enormous creatures are sometimes known |

to turn upon their persecutors with unbounded fury, destroying everything that meets them in their course, sometimes by the powerful blows of their flukes, and sometimes attacking with the jaw and head.*

No. 3.

* Plate No. 3, represents a large whale in the act of destroying a boat, with his head; of this occurrence the author was an eye-witness off the coast of Japan, on July 18th, 1832. Capt. W. Swain, of the Sarah and Elizabeth, of London, had with two other boats been engaged in chasing a large whale nearly the whole of the day; at about 4 p.m. the captain was considerably a-head of the other two boats, and had succeeded in striking the whale with the harpoon, and being a dexterous whaler, he succeeded in lancing the animal twice before it had recovered itself from the blow; the lance wounds having penetrated the cavity of the chest, caused the animal to eject blood from the nostril in large quantities; he however suddenly descended to the depth of about 40 fathoms, and as suddenly rose, striking the boat with excessive force, which threw it into the air in fragments, with the men and every thing contained therein; the |

Numbers of unfortunate whalers and their boats have been destroyed in this way. It is however fortunate that the large whales seldom shew this violent disposition to defend themselves by assailing their enemies. Accidents also frequently occur from the violent convulsive movements of a wounded whale, when men, although much bruised, managed to support themselves with the pieces of the boat, oars, &c. for about three quarters of an hour, when they were relieved from their perilous situation by the arrival of one of the other boats; all the time they remained in the water the whale continued near them, and also several sharks, which were attracted by the blood which flowed from the whale in great abundance: the men however had the courage, although ten were now in one boat (and the other had not yet arrived,) to make a second attack upon the whale, by remaining at a distance and throwing the lance; they managed in this way to give him several more wounds, when the poor animal descended and never rose again to the surface, an occurrence which not unfrequently happens, owing, of course, to the greater specific gravity of the individual, probably caused by a greater development of bony and muscular structures. The ship was all the time of the above occurrence about four miles to leeward, and could not therefore render the slightest assistance to the unfortunate crew, but before sunset they had the good fortune to reach the ship in safety, having however had the chagrin, after a day spent in excessive toil, to lose a favorite boat, with all her contents, and more than that an enormous whale (worth £500.) the last wanted to complete the voyage. The engraver has, unfortunately, in this plate represented the boat with a flat stern, a form which is never given to a boat intended for the southern whale fishery, but the reader will probably be kind enough to overlook this unimportant error, as a perfect correct view of the kind of boat employed in this fishery, is presented in plate No. 1. |

suffering the last pangs of his numerous and deep wounds. When the lance has been used effectively so as to wound some important vital organ, the animal generally throws up blood in large quantities from the blow hole, becomes convulsed, lashing the waves violently with his tail, passing very rapidly along tinging the water with his blood as he swims; and it is a curious fact, that under these circumstances he always describes in his course a segment of a circle. In this state the whale is said to be in his "flurry." When dead, the body always turns on its side, probably from the greater weight of the spine and dorsal muscles. In calm weather, great difficulty is sometimes experienced in approaching the whale, on account of the quickness of his sight and hearing. Under these circumstances the fishers have recourse to paddles instead of oars, and by this means can quietly get near enough to make use of the harpoon. When first struck, the whale generally "sounds," or descends perpendicularly to an amazing depth, taking out perhaps the lines belonging to the four boats, 800 fathoms! afterwards when weakened by loss of blood and fatigue, he becomes unable to "sound," but passes rapidly along the surface, towing after him perhaps three or four boats. If he does not turn, the people in the boats draw in |

the line by which they are attached to the whale, and thus easily come up with him, even when going with great velocity, he is then easily lanced and soon killed. Numberless stories are told of fighting whales, many of which however are probably much exaggerated accounts of the real occurrences. A large whale, called "Timor Jack" is the hero of many strange stories, such as of his destroying every boat which was sent out against him, until a contrivance was made by lashing a barrel to the end of the harpoon with which he was struck, and whilst his attention was directed and divided amongst several boats, means were found of giving him his death wound. In the year 1804, the ship Adonis being in company with several others, struck a large whale off the coast of New Zealand, which "stove" or destroyed nine boats before breakfast, and the chase consequently was necessarily giving up. After destroying boats belonging to many ships, this whale was at last captured, and many harpoons of the various ships that had from time to time sent out boats against him, were found sticking in his body. This whale was called New Zealand Tom, and the tradition is carefully preserved by whalers. Not boats only, but sometimes even ships have been destroyed by these powerful creatures. It is a well authenticated fact, that an American whale ship, the Essex, was destroyed in the South |

Pacific Ocean by an enormous sperm whale. While the greater part of the crew were away in the boats, killing whales, the few people remaining on board saw an enormous whale come up close to the ship, and when very near he appeared to sink down for the purpose of avoiding the vessel, and in doing so he struck his body against some part of the keel, which was broken off by the force of the blow and floated to the surface; the whale was then observed to rise a short distance from the ship, and come with apparently great fury towards it, striking one of the bows with his head with amazing force, and completely "staving it in." The ship of course immediately filled, and fell over on her side, in which dreadful position the poor fellows in the boats saw their only home, and distant from the nearest land many hundred miles; on returning to the wreck they found the few who had been left on board hastily congregated in a remaining whale boat, into which they had scarcely time to take refuge before the vessel capsized -- they with much difficulty obtained a scanty supply of provisions from the wreck, their only support on the long and dreary passage before them to the coast of Peru, to which they endeavored to make the best of their way. One boat was fortunately found by a vessel not far from the coast, in it were the only survivors of the unfortunate crew, three in number -- the remainder having miserably perished under unheard of suffering |

and privations. These three men were in a state of stupefaction, allowing their boat to drift about where the winds and waves listed. One of these survivors was the master; by kind and careful attention on the part of their deliverers, they were eventually rescued from the jaws of death to relate the melancholy tale. §4. After the death of the whale, the next steps are to remove the fat and spermaceti, and to extract the oil, the reward of so much exertion and dangerous enterprise. This process, which is called "cutting in," is divided into two stages, the "cutting in" and "trying out;" in these operations the utmost cleanliness is observed. Immediately after the whale has been killed, it is brought alongside the ship to be "cut in," which is done by means of instruments called "spades" and pullies. A man descends upon the carcase after a hole has been cut with a spade, by a person stationed at the side of the ship, into which a large hook is inserted, which is attached to pullies; the blubber is then cut with the spade in a narrow strip, in a spiral direction around the body of the whale, which is drawn up by the pullies, and removed much in the way a spiral roller or bandage might be. Of course as the "blanket pieces" ascend, the body of the whale performs a rotatory motion, until the whole is stripped off. The head is cut off and hoisted upon end by the pullies, and the fluid or semifluid spermaceti is drawn |

up by means of a bucket and pole constructed for the purpose. The blubber, when on board, passes through the "flinching" room, and being cut into thin pieces upon blocks called "horses," it is thrown into the "trypots," into which the oil is extracted by heat. These operations are not attended with any offensive smell, and are very quickly performed, as 80 barrels of oil may be stowed in the hold of the ship in less than three days after the destruction of the animal. §5. It may be useful to the whaler, and interesting to the reader, to give, in this place, an account of the various parts of the world, in which the Sperm Whale has been seen in the greatest numbers, and where the masters of ships generally resort to for the purpose of fishing. The under mentioned places have all known as favourite situations to the Sperm Whale: --

SOUTH PACIFIC.

new guinea and parts adjacent. On the north coast of New Guinea, from 140° to 146°, east longitude -- New Ireland, from Cape St. George to Cape St. Mary -- from Squally Island to the northward. from St. George's Channel to the southward -- on the east coast of New Britain -- about the Islands of Bougainville -- and Bouka Bay -- particularly off the northern shore of Bougainville, as far as the Green, |

or Bentley's Islands -- Solomon's Archipelago, as far to the northward as Howe's Group -- Malanta, along the north east and south west parts, and in the Straits, as far to the north as Gower's Island -- off the west points of New Hanover.

king's mill group.

Off any part of these Islands, but more particularly off the south west parts of Roach's Island, distant from the land 30 or 40 miles, and off the south west portion of Byron's Island.

equinoctial line.

From the longitude of 168° to 175° east.

ellis' group.

Off the south side, distant from the Land 3 or 4 miles.

mitchell's group.

Off the south side, distant from the Land 3 or 4 miles.

rotumah.

Off the south east side, distant from the Land 15 to 30 miles.

new holland.

Off the eastern coast, from the latitude of 34° to 25°.

new zealand.

From the east Cape to north Cape, the Land dipping, and off shore to the north eastward, as far as Curtis's Island.

tongataboo.

Off Middleburgh Island and Isles adjacent. |

navigator islands.

South west side of Tootooillah.

AMERICAN CONTINENT.

peru. Off the shore, from longitude west 90° to 130°, in the latitude 5° south to the line.

galapago's islands.

Off the south head of Albemarle Island.

middle ground.

Between the continent and the Galapago's Islands.

malucca islands.

Off the north point of Moratay, and off the east and west sides of Gillolo; also off the adjacent Islands.

bouton.

Off the east side, and in the Straits of that name.

timor.

In the straits of Timor -- off the south side of Omby -- off the south side of Pantor -- and off the south side of the adjacent Islands as far as Sandle Wood Island to Java Head -- and off the Shore, in latitude 12° to 16°, and longitude from 112° to 120°. |

new holland.

Along the north west coast.

mahee islands.

Off the eastern side.

Off Johanna Island in the Mozambique Channel.

chili.

Off the Island of Chiloe to the northward -- along the coast of Chili, and as far south as 37°, the Land dipping.

california.

Off Cape St. Lucas, and off the Tres Maria Islands.

japan.

Along the coast -- Volcano Bay -- Loo Choo Islands -- off shore grounds of Japan, from the latitude of 28° to 40°.

bonin islands

All round them, within 40 miles.

china sea, &c. &c. &c.

Teape & Son, Printers, Towere-hill.

|

LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS

Baddeley, Thomas, Esq. Storer-street, Bedford-square. Bell, Thomas, Esq. Surgeon, New Broad-street. (3 copies) Beale, Mr. John, Mile End-road. Beale, Mr. Benjamin, Oxford. Bellingham, H. Esq. Surgeon, Mile End-road. Berry, Mr. F.S. jun. Storer-street, Bedford-square. Birt, Mr. W.R. York-street, Whitechapel. Birt, Mr. Hugh, Sutton, Sussex. Blenman, Mr. John, Dempsey-street, Bedford-square. Blyth, & Son, Messrs. Ship Owners, Limehouse. (3 copies) Blyth, James, Esq. Trump-street, City. Busk, G. Esq. Surgeon to H.M.S. Dreadnought, Seamen's Hospital. (2 copies) Burton, T.J. Esq. Wellclose-square. Burgess, S. Esq. Henry-street, Vauxhall. Clay, William, Esq. M.P. for the Tower Hamlets. Castles, Dr. T. F.L.S. Carey, S. Esq. H.M.S. Dreadnought, Seamen's Hospital. Cain, William, Esq. Surgeon, Whitechapel-road. Cartwright, Mr. Richard, Chapman-street, St. George's East. Chapman, Thomas, Esq. Great Prescot-street. Clark, Mr. William, Rotherhithe. Collier, Mr. Green-street, Mile End. Connell, Mr. Dalrymple, John, Esq. Broad-street, Surgeon to the Opthalmic Infirmary, Moorfields, &c. &c. &c. (2 copies) Dawson, Mr. Frederick, Barne's-place, Mile End-road. Dawson, Mr. Henry, ditto. Dunsterville, Mr. George, Crown-street, Finsbury-square. Enderby, C.H. & G. Esqrs. Great St. Helen's, Ship Owners. (3 copies) Eclectic Society of London, Library of the Ellis, Mr. Thomas, Cheshunt. Fox, Dr. C.J. Billiter-street, Physician to St. John's British Hospital, and to the Tower Hamlets Dispensary. Francis, G. Esq. Great Prescot-street. Frost, Mrs. E. Rufford, Notts. Friends of Freedom, Library of the, Fox Tavern, Russell-street, Mile End. Gordon, J.B. Esq. Poplar, Ship Owner (3 copies) Huggins, W.J. Esq. Leadenhall-street, Marine Painter to the King. (six copies) Harkness, Miss, Rodney-terrace, Bow-road. |

Hooker, P. Esq. Raven-row, Mile End-road. Harvey, Mr. T. Cannon-street East. Jenkins, C.E. Esq. K.M. Great Prescot-street, Surgeon to St. John's British Hospital, &c. &c. &c. (10 copies) Jenkins, Mr. N. Fox-tavern, Russell-street, Mile End-road. Johnstone, Christopher, Esq. H.M.S. Dreadnought, Seamen's Hospital. Kisch, J. Esq. Surgeon, Broad-street-buildings. (3 copies) King, James, Esq. Surgeon, H.M.S. Dreadnought, Seamen's Hospital. Lancaster, Mr. Charles, Philpot-street. Lewis, Miss C. Globe-road, Mile End. Lewis, Joseph, Esq. Hay, Breconshire. Linton, W.S. Esq. Islington. (2 copies) Merrett, W.G. Esq. Surgeon, Great Alie-street. Moss, Mr. J. New-street, Commercial-road. Miers, T. Esq. Whitechapel. Newson, Mr. William, Mile End-road. Nicholson, Mr. R. New-road, St. George's East. Newling, Mr. J. Nassau-place, Commercial-road. O'Leary, Mr. T. Rutland-street, Commercial-road. O'Leary, Mr. J. ditto. Puddicombe, E.D. Esq. Hamilton-terrace, St. John's Wood. Parker, R. Esq. High-street, Mary-le-bonne. Piper, H. Esq. Aldersgate-street. Quain, Jones, Esq. A.B. M.B. Great Coram-street, Lecturer on Anatomy and Physiology to the London University Quain, Richard, Esq. Demonstrator of Anatomy to the London University, and Surgeon to the Charing Cross Hospital. Rounce, Mr. Thomas, Rotherhithe. Ross, Mr. F. Poplar. Self, William, Esq. Surgeon, Commercial-road. Sturge, Thomas, Esq. Newington Butts, Ship Owner. (10 copies) Staples, J. Esq. Half- Moon-street, Piccadilly. Storey, John, Esq. Surgeon, Mile End-road. Stacey, Mr. Rupert-street, Goodman's-fields. Stephens, William, Esq. Rodney-terrace, Bow-road. Snowden, Capt. Deptford-road. Skelton, Capt. Commercial-road. (2 copies) Tyrrell, Frederick, Esq. Bridge-street, Blackfriars, Surgeon and Lecturer on Surgery to St. Thomas's Hospital, and Surgeon to the Opthalmic Infirmary, Moorfields. Travers, Joseph, Esq. St. Swithin's-lane, City. Tonybee, Mr. Joseph, Gerrard-street, Soho. Tuckett, Frederick, Esq. H.M.S. Dreadnought, Seamen's Hospital. Tranter, Polydore, Esq. Jersey. Usher, James, Esq. Oldford. Wilmott, Mr. E. Oxford-street, Mile End. Young, G.F. Esq. M.P. Limehouse. (2 copies) |

THOMAS BEALE, 1807-1849Thomas Beale, an Englishman, was born in 1807. In 1830, at the age of 22 or 23, he sailed for the South Seas as a physician on the London whaling ship, the Kent (William Lawton, captain). On June 1, 1832, Beale exchanged berths with a Doctor Hildyard while both vessels were near the Bonin Islands. He then returned to England on board the Sarah and Elizabeth (William Swain, captain) in February, 1833. In 1835 Beale published for subscribers a fifty-eight page booklet with a long title: A Few Observations on the Natural History of the Sperm Whale, with an account of the Rise and Progress of the Fishery, and of the Modes of Pursuing, Killing, and "Cutting In" that Animal, with a List of its Favourite Places of Resort (London, Effingham Wilson, 1835). The apparent success of this fifty-eight page publication, led Beale to revise and expand it in the more substantial The Natural History of the Sperm Whale: its Anatomy and Physiology -- Food -- Spermaceti -- Ambergris -- Rise and progress of the Fishery -- Chase and Capture -- "Cutting In" and "Trying Out" -- Description of the Ships, Boats, Men, and with an Account of its Favourite Places of Resort. To which is added, a sketch of a South-Sea Whaling Voyage; Embracing a Description of the Extent, as well as the Adventures and Accidents that Occurred During the Voyage in which th Author was Personally Engaged. (London, John van Voorst, 1839) which was published in 1839. Joan Druett, in her very interesting book Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail (Routledge, New York, 2001) writes of Beale:

Beale's Natural History was also used by Herman Melville in the writing of Moby Dick which was first published in 1851. |

|

Source.

Thomas Beale.

A PDF of this booklet may be found at the website of the

Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (Flanders Marine Institute), Oostende, België.

Last updated by Tom Tyler, Denver, CO, USA, Dec 24, 2024.

|

|