|

|

|

Publication Number Ten

of the Marine Research Society

Copyright, 1925, By

The Marine Research Society

Printed in the United States

The Southworth Press Portland, Maine |

|

Note

This version of Dow's Whale Ships and Whaling A Pictorial History of Whaling During Three Centuries uses images that correspond to the sources used by Dow in 1925 and found on current (November 2024) websites. Otherwise, images from the 1925 publication are used. Most of the high quality images of old prints of whaling scenes are presented here courtesy of the MIT Museum which now houses the Allan Forbes collection. Where a better quality image of early 20th century photographs could be found, they were used here without attribution. Tom Tyler, Nov 27, 2024. |

|

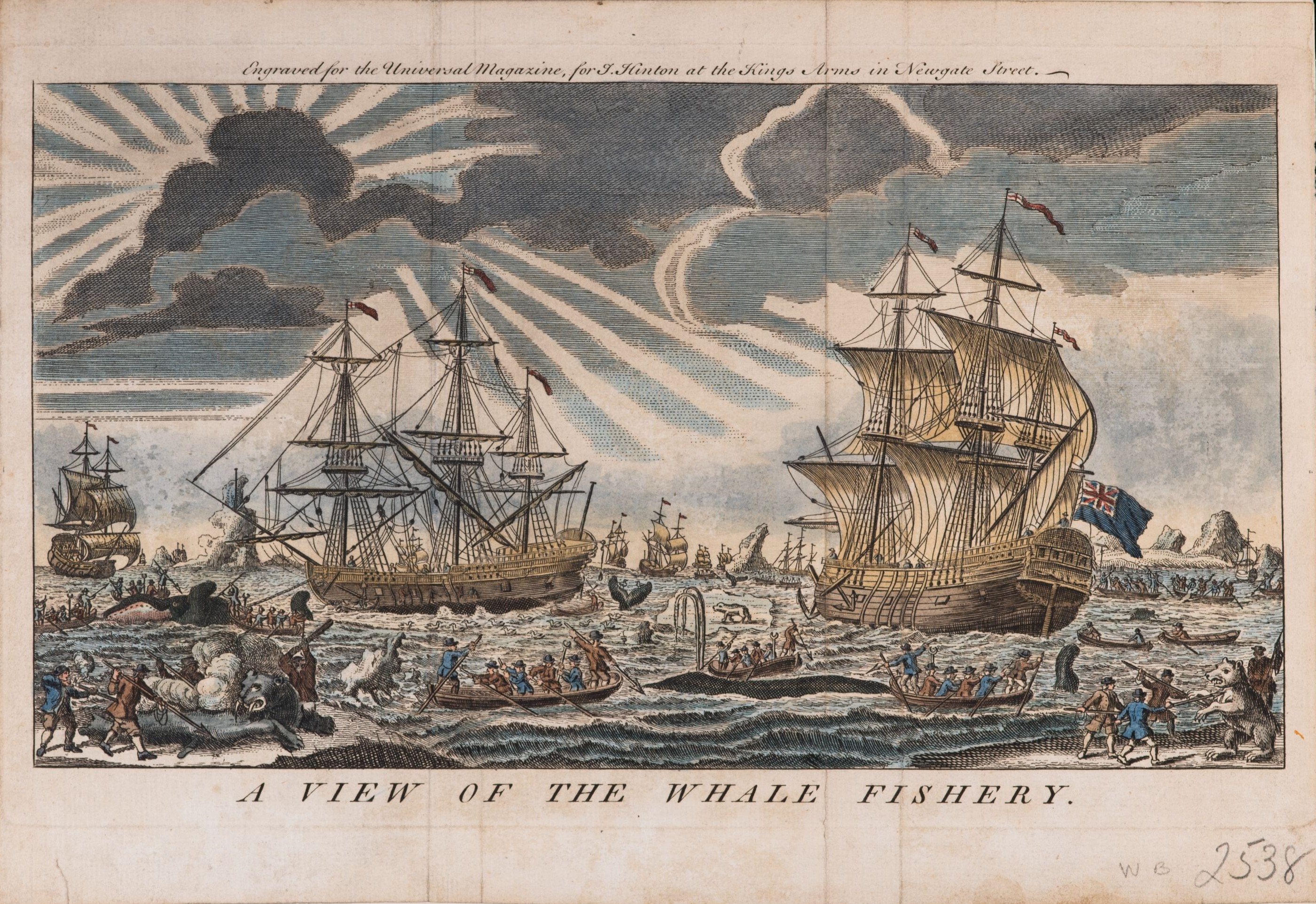

PREFACE The keen interest in whale ships and whaling that exists at the present time has led to the production of this volume. Many books have been written descriptive of the industry and of the lives and adventures of whalemen but, so far as known, no effort has ever been made to present a comprehensive pictorial survey showing the whale ships of all periods. Aside from the modern use of the whaling gun, the methods followed in killing the quarry have changed but little during historic times; but ships have changed with the centuries and the following illustrations will be found to have preserved a record of whalers and whaling valuable alike to those who would study the evolution of a dying industry and also to the builder and collector of models of these ships. As a suitable background for this pictorial history of whaling, especially when viewed by American eyes, it has seemed fitting to include some account of the whale fishery in colonial New England. Public archives and contemporaneous newspaper accounts have been drawn upon as well as the gatherings of local historians; but the principal source of information has been the painstaking survey of the industry made by the late Alexander Starbuck and published in the "Report of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries for the year 1875-1876." The nucleus from which the following collection of illustrations has grown was found in the "Allan Forbes Collection of Whaling Pictures," a wonderful gathering of all kinds of material relating in any way to the subject. Mr. Forbes generously made available the resources of this great collection – so large in its compass that the difficulty has been to decide what not to use. Mr. A. G. H. Macpherson of Alverstoke, Hants, England, at [v]

|

some personal inconvenience, threw open the resources of his remarkable collection of marine and naval prints, probably the largest in the world, and caused photographs to be made of rare prints and early engravings relating to the field of European whaling; and Captain Harry Parker, the well-known London dealer in naval prints, most generously placed his selected gatherings at our command. Mr. Frank Wood, the curator of the Bourne Whaling Museum at New Bedford, Mass., has aided the work in every way and finally consented to write the Introduction to the volume. Colonel E. H. R. Green of New Bedford, with a generous spirit of cooperation, had many photographs made of the old-time whaler Charles W. Morgan, purchased by him, and many of these photographs are here reproduced. Thanks are also due to the officials of the Peabody Museum of Salem; to Miss Sarah L. Dunfee, Curator of the Marine Museum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and to all others who may have aided in any way in the production of this volume. |

|

CONTENTS

[vii]

|

|

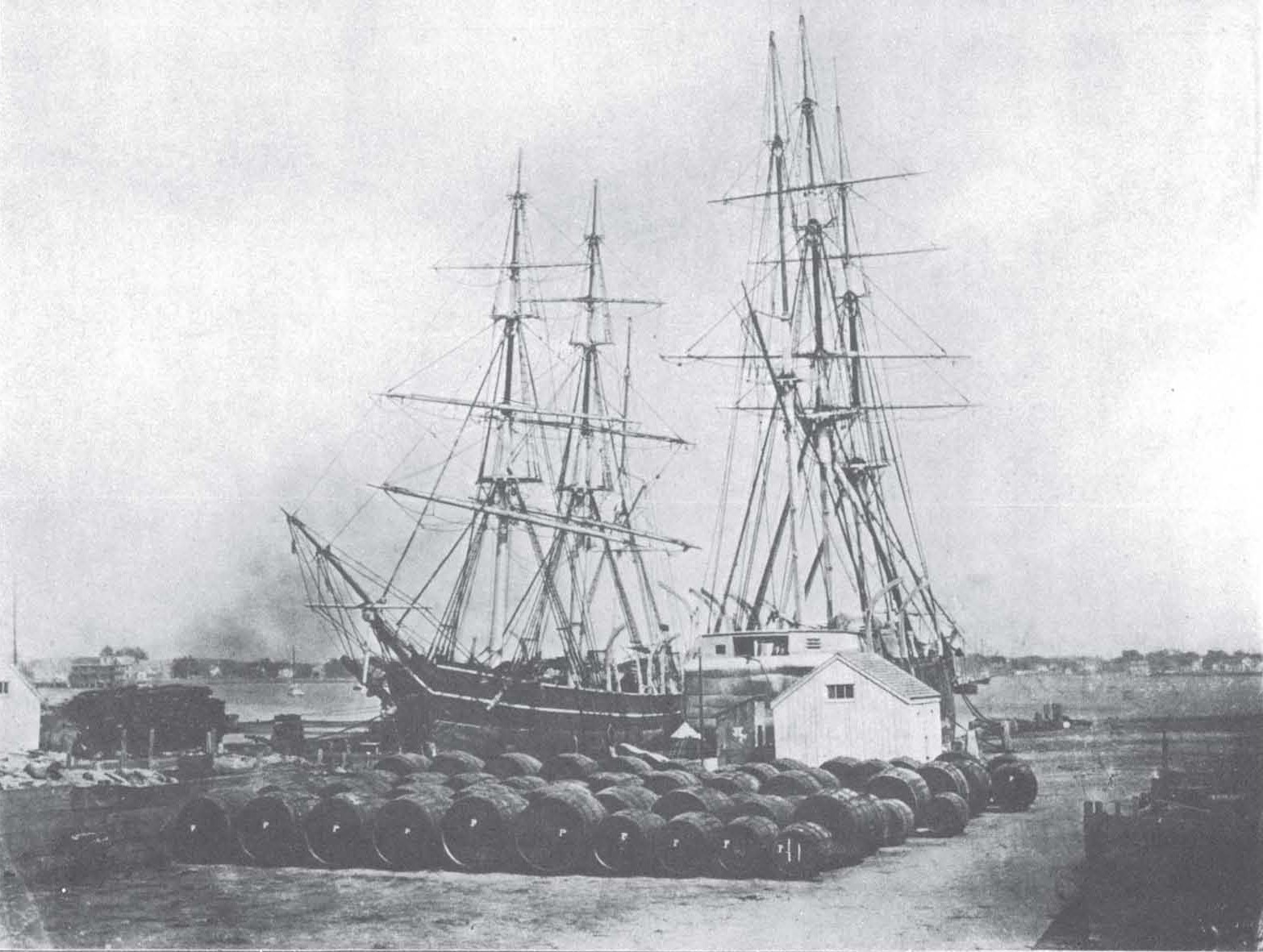

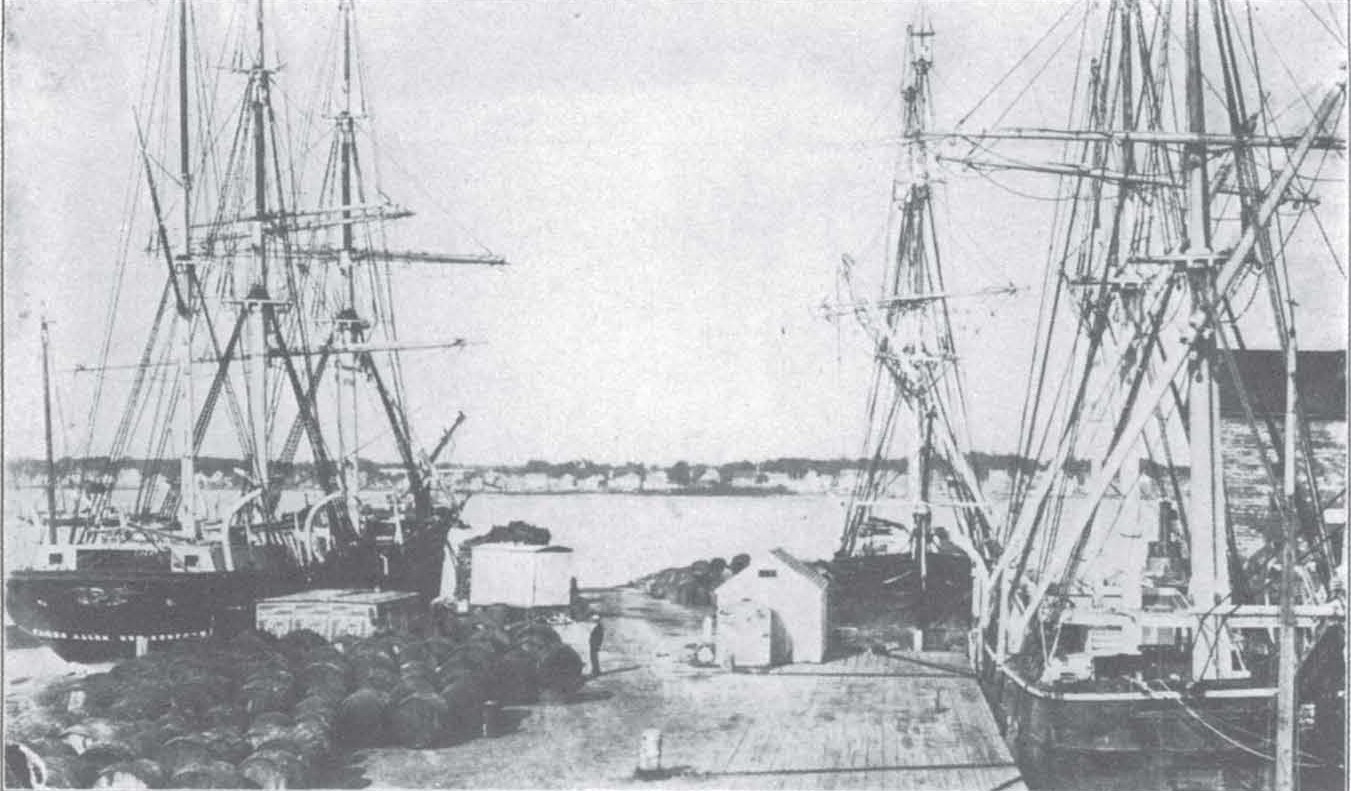

INTRODUCTION THERE was a time, within the memory of a great many citizens of New Bedford, when the wharves of the city were swarmed with ships and barks, whose hundreds of masts fringed the sky-line like the bayonets of a great army marshalled in battle array. Today we look in vain for one of those grimy, storm-stained square-riggers. Cotton mills, with hovering clouds of smoke, now greet the eye as it looks along the water-front. The clack of looms and the whirr of spindles greet the ear. Only in one way does the past come back to us and that way, curiously enough, is through the sense of smell. The tiers of barrels of whale oil, covered with sea weed, as was the custom, formerly occupied much space on the wharves and more or less of the oil would seep out through the cracks in the barrels, and permeate the timbers and the soil on the wharves. The odor is still strong. Like the odor of the mignonette shut between the leaves of a favorite old book, it recalls a past. And we have under consideration a past that is worth recalling. Communities like Nantucket, New Bedford and New London grew to prominence and waxed prosperous on whaling and its subsidiary occupations alone. Bold journeys were made to all parts of the ocean, and not a little of the exploration done in the last century may be attributed to the whalemen. And these whalemen formed, in a sense, a race apart. In towns where whaling was an exclusive industry, boys were born with the fever of the sea in their veins. Distant journeys to quasi-legendary lands, where strange folk lived; dangers of storms and of uncharted seas, of merciless ice-floes in the Arctic, of the sickly heat in the equatorial Pacific; tremendous conflicts with the largest and most powerful creature known on this globe – all the mys- [ix]

|

tery, the glamor and the romance of whaling fed the flames of boyish imagination and desire. As youngsters, they listened to the tales of their elders, gazed with wonder at the queer men – the "Queequegs" that the ships often brought home. And they would watch the vessels leaving the harbor, as the proud masses of canvass would fade away at the horizon. And they would see them return, deep in the water with a lucky catch. But between the departure and the return, in watery realms far, far beyond the horizon, what brave glory there must be! But soon the imaginative boy became the practical man. Folk seemed to mature early in those days, back in the ’40s and ’50s, and crew lists show many a greenhand in his ’teens and many a master in his twenties. We often hear the saying, "A person never went whaling more than once."But this statement is true only of those young men who were lured to the whaling ports from up-country. The boys of the ports themselves, born and bred to the sea, if they answered to the call once, generally made whaling their career and rose through the ranks. If such young men made but one voyage, they considered it not as time lost, but as an important part of their education, fitting them for a better understanding of their life-work on shore, in counting-houses, in ship-owners’ offices, in any of the smaller businesses that were nourished by whaling. The hardships that they endured, the bravery that they were forced to display, the ennui they were taught to master, made of the whalemen a dauntless, strong-charactered race of men. We do not find the type today except in individual cases. Ofttimes we hear, too, that the whaleships were floating hells, and it is true that there were many deplorable abuses connected with whaling. But let us look for a moment at the brighter side. The whalemen of course had to put up with many of the disagreeable features of any life at sea, but, on the other hand, their work was not so exacting as the work on board a merchantman. In the latter case, the seamen were forced to climb the rigging a |

dozen or so times a day to furl some sail, to set another or to reef, for every little change in wind demanded a change in sail to maintain the highest speed possible. But the whaler never was concerned with speed; she sailed idly along – a whale might be found in one place as easily as in another. Then, too, the whaler was never kept as spic and span as a merchantman; there was not the continual holystoning for the men. And a witness to this phase of the whaleman’s existence, a witness to his leisure, exists in the large amount of scrimshaw work made from whales’ teeth and bone to carry home as gifts. Of course it goes without saying that when a whale was sighted, the whalemen were in for a hard j ob, a harder job than the uninitiated could ever appreciate. The chase, the capture, the cutting-in, the trying-out were dangerous and inordinately wearisome. But the chase and the capture, too, had their better sides. The love of a princely sport thrilled the whalemen when the cry of "blows" came from aloft. As trout-fishermen feel when they sense the first little nibble, the herald of joyful battle, so did the whalemen feel, when the harpoon buried itself into the giant whale – when the iron "tuk" and the chase was on and human ingenuity and courage and perseverance must be strained to their very limits. Like the trout-fishermen, indeed, but how far greater the danger, how far more difficult the art, how far more glorious the thrill! FRANK WOOD. New Bedford, July 31, 1925. |

|

THE WHALE FISHERY IN

COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND |

|

THE WHALE FISHERY IN

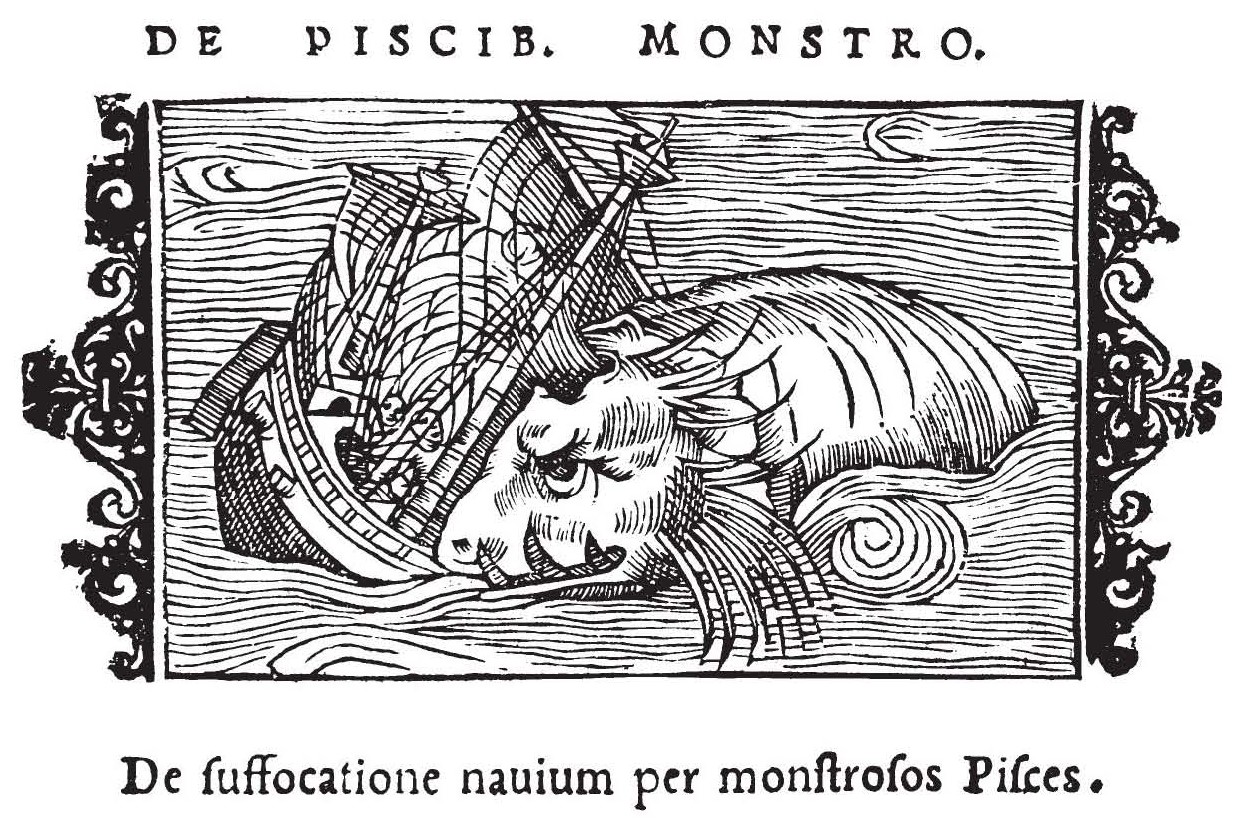

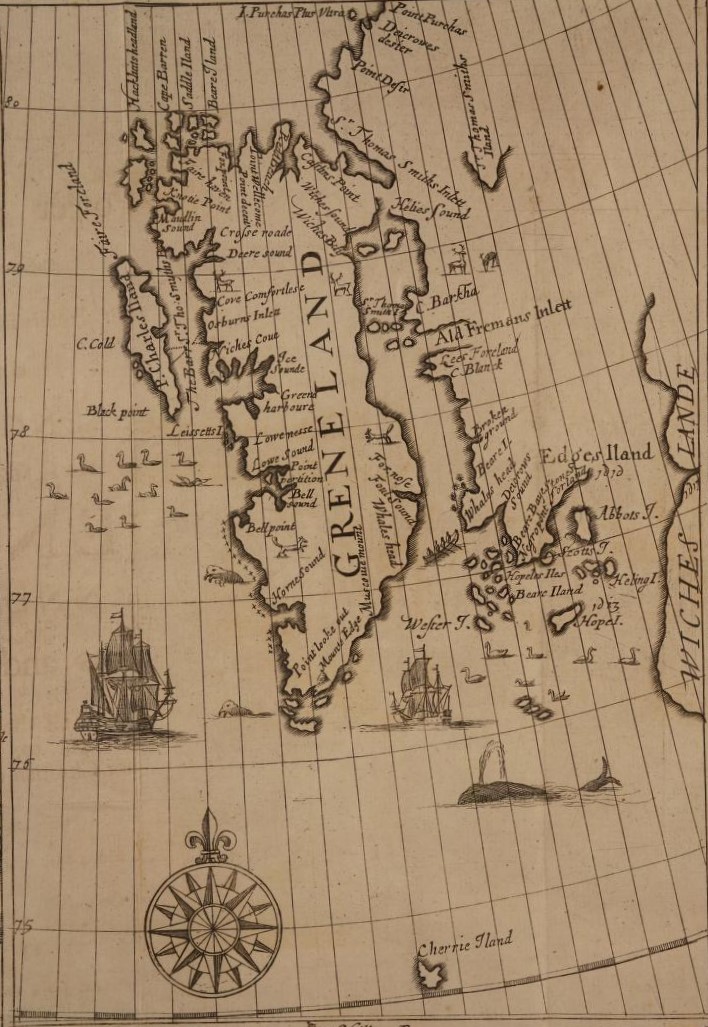

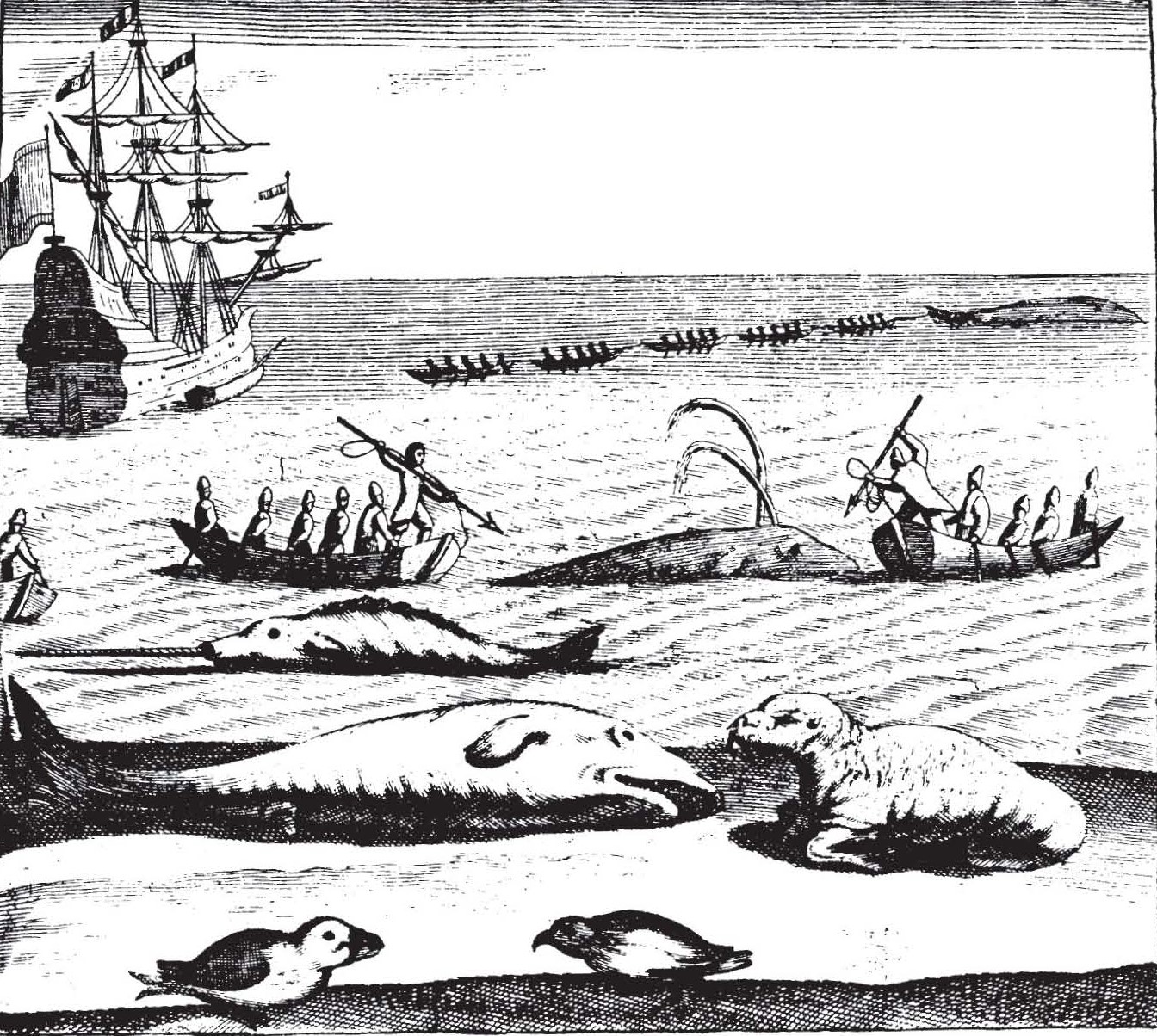

COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND MANY years before the first settlements were made in New England, fishing vessels from overseas frequented the coast. It was fully a century before the "Mayflower" sailed into Plymouth harbor, when French fishermen from St. Malo, Dieppe and Honfleur were catching cod on the banks off Newfoundland. English whale ships went to Cape Breton in the year 1593 and although they returned without having made any captures, yet they discovered on an island some eight hundred whale fins left by a Biscay ship that had been there three years earlier. Samuel de Champlain, the navigator and founder of the French settlements in North America, on returning to France from his second voyage, sailed from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River on August 18th, 1610, and when "about half way across, we encountered a whale, which was asleep. The vessel, passing over him, awakening him betimes, made a great hole in him near the tail, without damaging our vessel; but he threw out an abundance of blood. "It has seemed to me not out of place to give here a brief description of the mode of catching whales, which many have not witnessed, and suppose that they are shot, owing to the false assertions about the matter made to them in their ignorance by impostors, and on account of which such ideas have often been obstinately maintained in my presence. "Those, then, most skillful in this fishery are the Basques, who, for the purpose of engaging in it, take their vessels to a place of security, and near where they think whales are plenty. Then they equip several shallops manned by competent men and pro- [3]

|

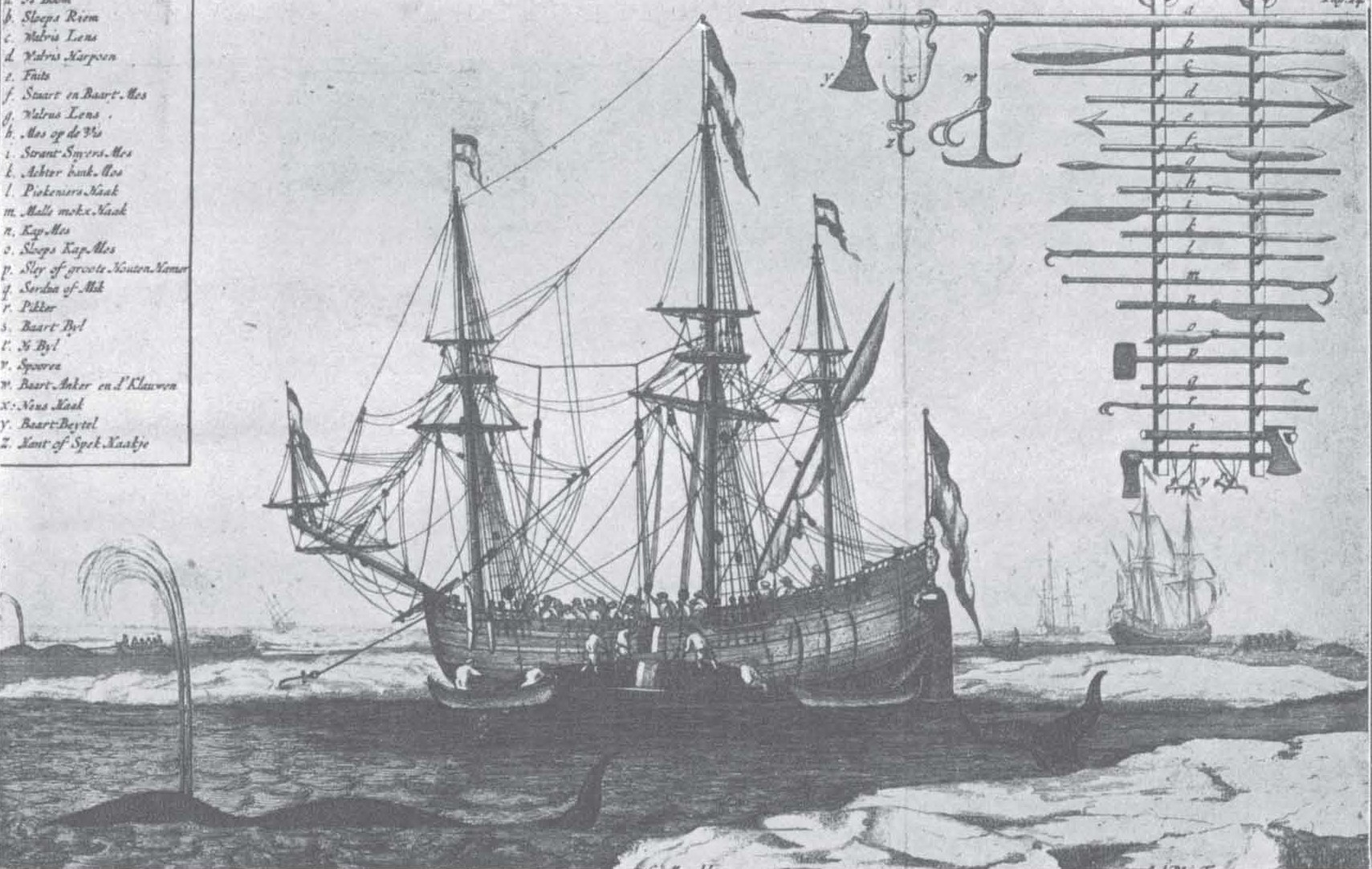

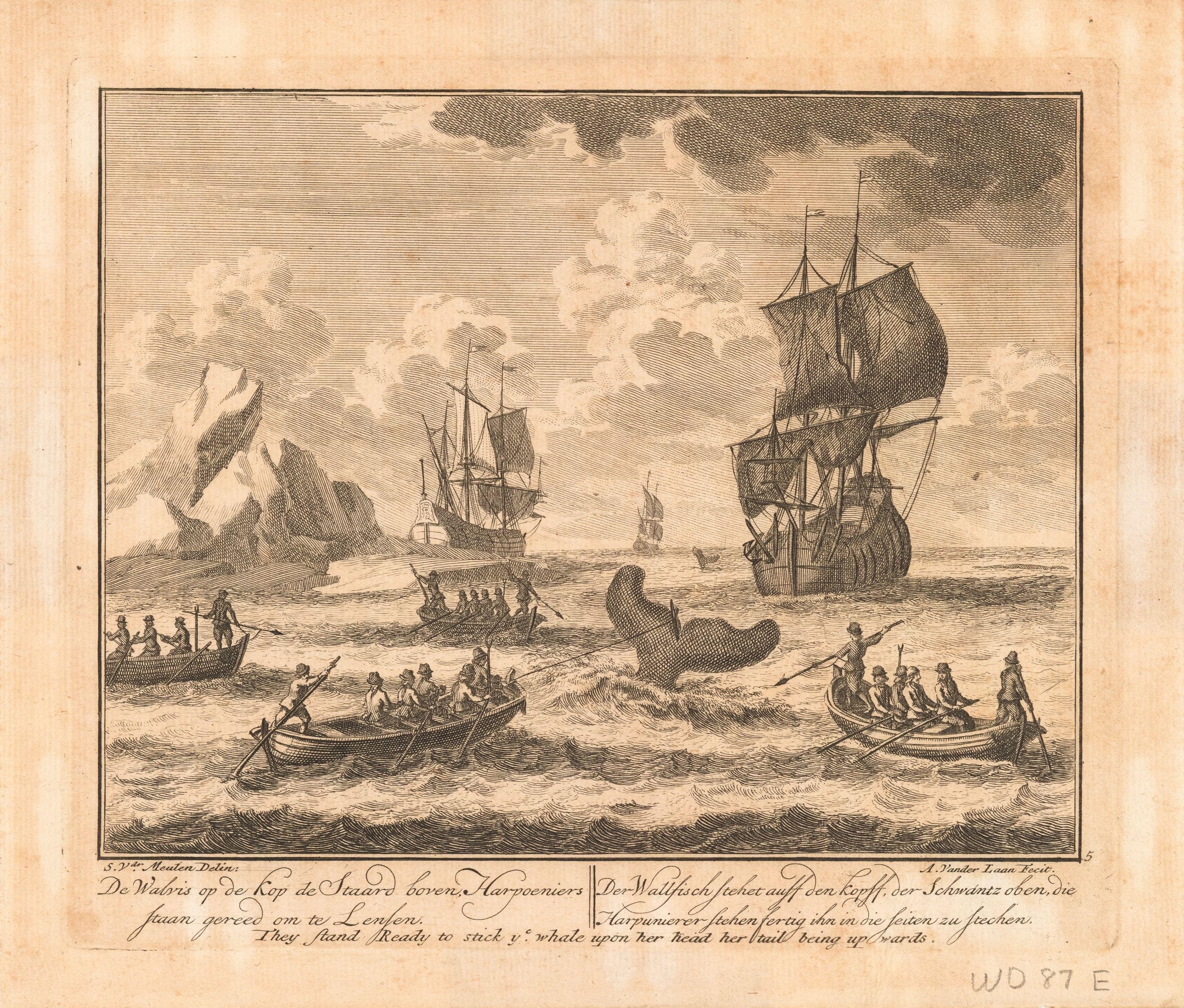

vided with hawsers, small ropes made of the best hemp to be found, at least a hundred and fifty fathoms long. They are also provided with many halberds of the length of a short pike, whose iron is six inches broad; others are from a foot and a half to two feet long, and very sharp. Each shallop has a harpooner, the most agile and adroit man they have, whose pay is next highest to that of the masters, his position being the most dangerous one. This shallop being outside of the port, the men look in all quarters for a whale, tacking about in all directions. But, if they see nothing, they return to shore and ascend the highest point they can find, and from which they can get the most extensive view. Here they station a man on the lookout. They are aided in catching sight of a whale by his size and the water he spouts through his blow-holes, which is more than a puncheon at a time and two lances high. From the amount of this water, they estimate how much oil he will yield. From some they get as many as one hundred and twenty puncheons, and from others less. Having caught sight of this monstrous fish, they hasten to embark in their shallops, and by rowing or sailing they advance until they are upon him. "Seeing him under water, the harpooner goes at once to the prow of the shallop with his harpoon, an iron two feet long and half a foot wide at the lower part, and attached to a stick as long as a small pike, in the middle of which is a hole to which the hawser is made fast. The harpooner, watching his time, throws his harpoon at the whale, which enters him well forward. As soon as he finds himself wounded, the whale goes down, and if by chance turning about, as he does sometimes, his tail strikes the shallop, it breaks it like glass. This is the only risk they run of being killed in harpooning. As soon as they have thrown the harpoon into him, they let the hawser run until the whale reaches the bottom; but sometimes he does not go straight to the bottom, when he drags the shallop eight or nine leagues or more, going as swiftly as a horse. Very often they are obliged to cut |

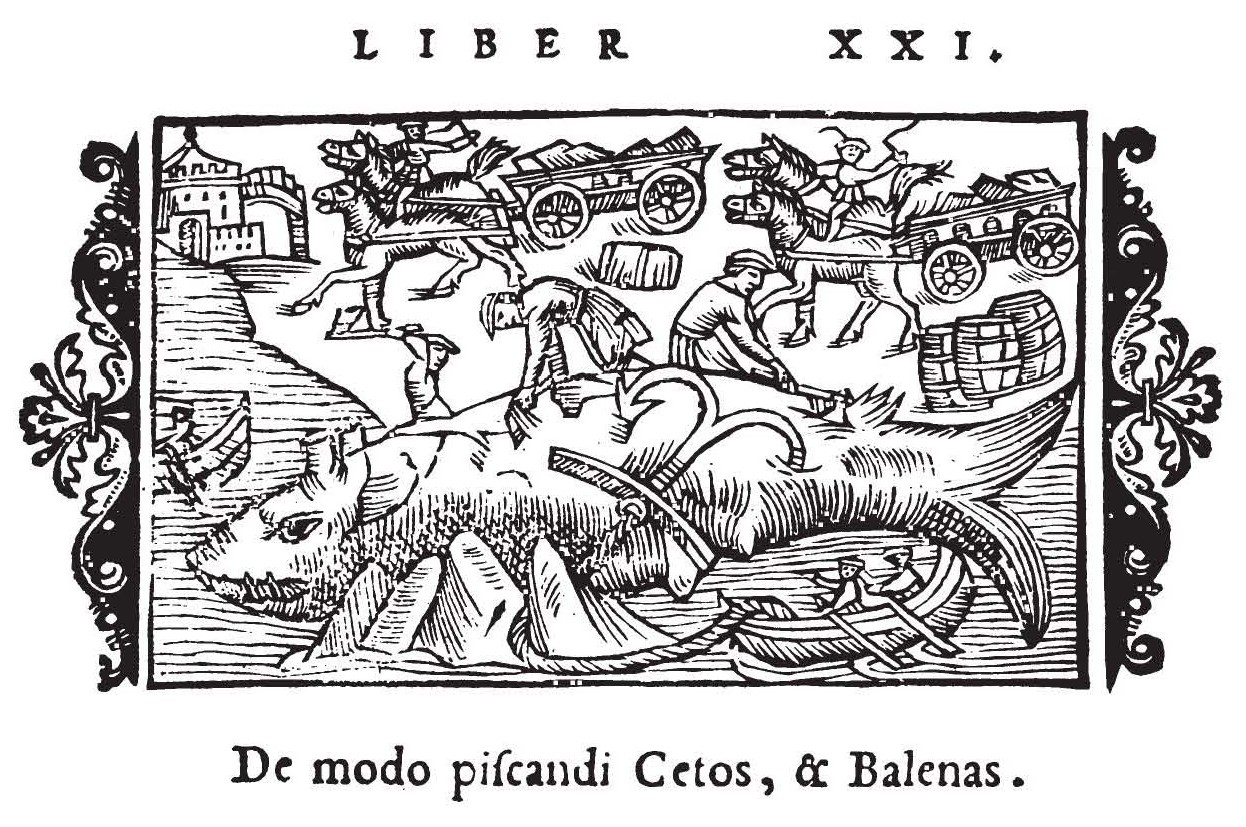

their hawser, for fear that the whale will take them under water. But, when he goes straight to the bottom, he rests there awhile, and then returns quietly to the surface, the men taking aboard again the hawser as he rises. When he comes to the top, two or three shallops are stationed around with halberds, with which they give him several blows. Finding himself struck, the whale goes down again, leaving a trail of blood and grows weak to such an extent that he has no longer any strength nor energy, and returning to the surface is finally killed. When dead he does not go down again. Fastening stout ropes to him, they drag him ashore to their headquarters, the place where they try out the fat of the whale to obtain his oil. This is the way whales are taken, and not by cannon-shots, which many suppose, as I have stated above."1 The date of the coming of the first ship sent out on a whaling venture to New England is not known, but it may have been in April, 1614, when Capt. John Smith arrived at Monhegan, off the coast of Maine, with two ships from London. "Our plot was there to take Whales, for which we had one Samuel Cramton, and divers others expert in the faculty. . . . We found this Whale- fishing a costly conclusion; we saw many and spent much time in chasing them, but could not kill any. They being a kind of Tubartes, and not the whale that yields Fins and Oils as we expected."2 Elsewhere he mentions that whales were common off the New England coast and when he arrived in London on July 18, 1614, after an absence of less than six months, his ship brought back furs, train oil (whale oil) and cor- fish (dried cod fish) the best of which sold at £ 5. the hundred. When the "Mayflower" came to anchor at Cape Cod, in December, 1620, the Pilgrims debated mightily whether they should remain there or find a settlement at Agawam, now Ips- 1 Voyages of Samuel de Champlain, New York, 1907, pp. 190, 191. |

wich, and one of the arguments advanced for remaining at Cape Cod was that "it was a place of profitable fishing, for large whales of the best kind for oil and bone came daily alongside and played about the ship. The master and his mate, and others experienced in fishing, preferred it to the Greenland whale fishery and asserted that were they provided with the proper implements, £ 300. or £ 400. worth of oil might be obtained."3 The Royal Charter under which the first settlements were made in the Massachusetts Bay, guaranteed to the colonists their rights to unrestricted fishing, in fact, it was a colony of fishermen that was at first contemplated. The Province Charter of 1691 also confirmed the rights of the colonists to "free Libertie of Fishing ... in the Seas thereunto adj oyning and of all Fishes Royall Fishes Whales Balene Sturgeon and other Fishes of what kind or nature soever." At that time whales undoubtedly were very numerous along the New England coast and also in deep water. When the Rev. Francis Higginson, the first minister at Salem, published his New Englands Plantation (London, 1630), he wrote of seeing a "great store of Whales and Grampusse" while on the voyage over, and five years later, when Rev. Richard Mather came over and became the minister at Dorchester, he wrote of seeing near the coast "mighty whales spewing up water in the air, like the smoke of a chimney, and making the sea about them white and hoary, as is said in Job, of such incredible bigness that I will never wonder that the body of Jonas could be in the belly of a whale."4 A still earlier voyager along the coast was Capt. George Waymouth, who sailed from Dartmouth, March 15, 1605, intending to visit the regions south of Cape Cod, but meeting with contrary winds after making his landfall, he bore away to the east-

3 Thatcher, History of Plymouth, p. 21. See also Morton, New England’s Memorial, p. 42. |

ward and anchored on the north side of the island of Monhegan off the coast of Maine. After exploring the nearby coast he sailed for England taking with him five Indians from the region of the Kennebec river. His narrative was published the same year and in it he describes the manner in which the Kennebec Indians captured the whale. "One especial thing is their manner of killing the whale, which they call powdawe; and will describe his form: how he bloweth up the water; and that he is twelve fathoms long; and that they go in company of their king with a multitude of boats, and strike him with a bone made in fashion of a harping iron fastened to a rope, which they make great and strong of the bark of trees, which they vear out after him; then all their boats come about him, and as he riseth above water, with their arrows they shoot him to death: when they have killed him and dragged him to shore, they call all their chief lords together and sing a song ofj oy; and those chief lords, whom they call Sagamores, divide the spoil, and give to every man a share, which pieces so distributed, they hang up about their houses for provision; and when they boil them, they blow off the fat, and put to their pease, maize, and other pulse which they eat."5 Samuel Purchas in his Pilgrimage describes in some detail how the English whalers pursued the whale at this time. Writing in 1612 he remarks: "I might here recreate your wearied eyes with a hunting spectacle of the greatest chase which Nature yieldeth : I mean the killing of a whale. When they espy him on the top of the water (which he is forced to for to take breath), they row toward him in a shallop, in which the harpooner stands ready with both his hands to dart his harping iron, to which is fastened a line of such length that the whale (which suddenly feeling himself hurt, sinketh to the bottom) may carry it down with him, being before fitted that the shallop be not therewith endangered; coming up again, they strike him with lances made 5 Mass. Hist. Soc. Colls. 3d series, Vol. VIII. |

for that purpose, about twelve feet long, the iron eight thereof and the blade eighteen inches – the harping iron principally serving to fasten him to the shallop, and thus they hold him in such pursuit, till after streams of water, and next of blood, cast up into the air and water (as if angry with both elements, which have brought thither such weak hands for his destruction), he at length yieldeth up his slain carcass as meed to the conquerors."6 Oils and fats were highly esteemed by our ancestors and occupied an important place in trade. Train oil, so-called, produced from the blubber of the whale, was used not only in the making of leather and for lighting, but also entered largely into the composition of the cargoes of vessels bound for London, Bristol and other English ports. Fish of various kinds were caught in such numbers that they were used as fertilizer in the corn fields, and fish oil became an article of export. In every household the animal fats were carefully preserved and used in the making of soap and candles. While candles made from tallow were in daily use in every home, all well- equipped kitchen fireplaces had their iron "betty lamps," used to light the inside of the pots and kettles in cooking, and other lamps of metal and even glass were used for lighting in prosperous homes. The streets in the larger towns were lighted but feebly. As late as the year 1668, the inhabitants of London, the first and largest city in the Kingdom, were ordered "to hang out candles duly to the accustomed hour, for the peace and safety of the city."It was not until 1716, that householders were directed to "hang out a lamp on every night between the second after the full-moon until the seventh after the new moon, from the hour of six in the evening until eleven." Whale oil furnished the best light and whalebone, or baleen, the fringed plates through which the right whale sifted its food, was used in clothing and in the arts. 6 Purchas his Pilgrimage, or Relations of the World ... in all Ages and Places, London, 1613. |

In the early days whaling was carried on in New England by means of boats from off shore, and most of the captures were made along the south shore of Massachusetts Bay and in the warmer waters south of Cape Cod. As early as 1641 the Great and General Court of Massachusetts "ordered and decreed, That if any ships or other vessels, be it friend or enemy, shall suffer ship-wreck upon our coasts, there shall be no violence or wrong offered to their persons, or goods, but their persons shall be Harboured and Releived, and their goods preserved in safety, till Authority may be certified, and shall take further Order Therein. Also any Whale, or such like great fish cast upon any shore, shall be safely kept or improved where it cannot be kept, by the town or other proprietor of the land, til the Generall Court shall set Order for the same."7 The right whale probably was very common along-shore at that time for there are numerous references to drift whales in the seventeenth century records of New England shore towns. These drift whales were prizes for the lucky finders and disputes at once arose as to the relative rights of the Colony and the finder. In 1652, the town of Sandwich, Mass., appointed six men to secure and divide oil-bearing fish that the Indians might cut up within the town limits. They also were to act as agents to receive the oil for the country.8 Ten years later the town of Eastham voted that a part of every whale cast ashore should be apportioned for the support of the ministry. History fails to relate what may have taken place when a whale was sighted in the breakers during the public exercise on a Sunday morning. From all drift whales the Colony claimed one hogshead or two barrels of oil to be delivered in Boston. In 1676, Edward Randolph, the British Agent in Boston, wrote home to the Lords of Trade, of the great quantity of whale oil made in the Plymouth Colony and again, in 1688, he wrote:

7 Book of the General Lawes and Libertyes concerning the Inhabitants of the Massachusets, Cambridge, 1660. |

"New Plimouth Colony have great profit by whale killing. I believe it will be one of our best returnes, now beaver and peltry fayles us."The same year a memorandum appears in the Colony Archives which embodies the universally recognized law of whalemen that "craft claims the whale."It specifies: "Furst : if aney persons shall find a Dead Whael on the streem And have the opportunity to toss herr on shoure; then ye owners to alow them twenty shillings; 2ly: if thay cast hur out & secure ye blubber & bone then ye owners to pay them for it 30s. (that is if ye whael ware lickly to be loast;) 3ly, if it proves a floatesom not killed by men then ye Admirall to Doe Thaire in as he shall please; – 4ly; that no persons shall presume to cut up any whael till she be vewed by toe persons not consarned; that so ye Right owners may not be Rongged of such whael or whaels ; 5ly, that no whael shall be needlessly or fouellishly lansed behind ye vitall to avoid stroy; 6ly, that each companys harping Iron & Lance be Distinckly marked on ye heads & socketts with a poblick mark: to ye prevention of strife; 7ly, that if a whael or whaells be found & no Iron in them; then thay that lay ye neerest claim to them by thaire strokes & ye natoral markes to have them; 81y, if 2 or 3 companyes lay equal claimes, then thay equally to shear."9 In November, 1690, the Plymouth Colony enacted a law requiring towns to appoint inspectors of whales and the following rules were set forth to govern their work: "1. All whales killed or wounded & left at sea the killers to repaire to the inspectors & give marks, time, place, which shall be recorded. "2. All whales brought or cast ashore to be viewed by inspector or deputy before being cut & marks & wounds recorded with time & place. "3. Any person cutting or defacing a whale before being viewed unless necessary shall lose right to it, & pay 10 £ to coun- 9 Massachusetts Archives, Vol. 125, leaf 80. |

ty, & fish to be seized by inspectors for owner’s use. Inspectors to have power to make deputy and allow 6s. per whale. "4. Those finding a whale a mile from shore not appearing to be killed by man shall be first to secure them, pay 1 hogshead of oyle to ye county for each whale."10 An original return made by one of these inspectors of whales is now in the possession of Mr. Lawrence W. Jenkins of Salem, and reads as follows: – "Decemr ye 3 1724 I was desired by Obediah Lamson to obsarve the marks of a whale cut up by him at Duxborough beach which ware as folleth. A short bone with 2 iarnholes one on her rite side about 6 feete abaft her spouts w’h iarn I gug mortal the other about 4 feete back of that & sumthing on the left side of her back boane not mortal and I gudg pricked with a lance one on the rite fin near the j oynt. I suposed this fish to be killed 4 or 5 days be fore this date. "Joshua Soule." Whaling alongshore began early on Long Island and it is probable that the first organized whale fishing on the coast began there. The town of Southampton, at the eastern end of Long Island, was settled in 1640 by men from Lynn in the Massachusetts Colony, and four years later the town was divided into four wards, with eleven persons in each ward, to care for drift whales that might be cast ashore. Two persons from each ward (selected by lot) were charged with the duty of cutting up the whale, "and every Inhabitant with his child or servant that is above sixteen years of age shall have in the Division of the other part [i. e. the part that remained after the cutters had deducted the double share to which by vote they were entitled] an equall proportion provided that such person when yt falls into his ward a sufficient man to be imployed aboute yt."11 In 1645, the town

10 Plymouth Colony Records, VI, pp. 252-3. |

voted that no man should take or carry away any whale cast ashore within the limits of the town without an order from a magistrate under a penalty of twenty shillings, and anyone finding a whale, on notifying a magistrate should be allowed five shillings. "And yt is further ordered that yf any shall finde a whale or any peece thereof upon the Lord’s day then the aforesaid shillings shall not be due or payable."The historian of Southampton remarks "this last clause, appears to be a very shrewd thrust at ‘mooning’ on the beach on Sundays." A few years later it was customary to fit out expeditions of several boats to go whaling along the Long Island coast. These expeditions frequently would be away from home for a week or two and camps on shore would be made at night. Indians were employed in the crews even at that early date, the payment for services usually being made in oil. In 1668, Indian whalemen were paid wages at the rate of three shillings per day. The whaling season was from November 1 st to April 1 st. There were many complaints from the Indians to the government. In early deeds of the town of Easthampton, Long Island, the Indian grantors were to be allowed the fins and tails of all drift whales ; but in the deed of Montauk Island, the Indians and white settlers were to share equally. Easthampton voted in 1651 "that Goodman Mulford shall call out ye Towne by succession to loke out for whales." A memorandum appears among the papers of the British Secretary of State, under date of 1667, bearing upon affairs in New England, in which he records the fact that the sea was rich in whales near Delaware Bay, but that they were to be found in greatest number about the end of Long Island comparable with the richness of the cod fishery about Nova Scotia. 12 In 1672, a memorial was presented to the Court at Whitehall, setting forth that the towns of Easthampton, Southampton and Southwold, on Long Island, had "spent much time and paines, 12 Col. State Papers, Colonial Series (1661-1668), p. 533. |

and the greatest part of their Estates, in settling the trade of Whale-fishing in the adjacent seas, having endeavoured it above these twenty years, but could not bring it to any perfection till within these 2 or 3 yeares last past. And it now being a hopefull trade at New Yorke, in America, the Governor and the Dutch there do require ye Petitioners to come under their Patent, and lay very heavy taxes upon them beyond any of his Maties subjects in New England, and will not permit the petitioners to have any deputys in Court, but being chiefe, do impose what Laws they please upon them, and insulting very much over the Petitioners threaten to cut down their timber which is but little they have to make Casks for oyle, altho’ the Petrs purchased their landes of the Lord Sterling’s deputy, above 30 yeares since, and have till now been under the Government and Patent of Mr Winthrop, belonging to Conitycut Patent, which lyeth far more convenient for ye Petitioners assistance in the aforesaid Trade."13 This memorial seems to indicate that off-shore whaling in boats from the eastern end of Long Island probably began about 1669-1670. A letter written in April, 1669, by Samuel Maverick of Boston, to Col. Richard Nicolls, the first English governor of New York, has an interesting bearing upon this point, showing that about the same time small vessels were being fitted out in Boston to go a-whaling. He writes: "On ye East end of Long Island there were 12 or 13 whales taken before ye end of March, and what since wee heare not; here are dayly some seen in the very harbour, sometimes within Nutt Island. Out of the Pinnace the other week they struck two, but lost both, the iron broke in one, the other broke the warpe. The Governor hath encouraged some to follow this designe. Two shallops made for itt, but as yett wee doe not heare of any they have gotten. "14 The same year he wrote that twenty whales had been captured that spring.

13 New York Colonial MSS. VI, p. 75. |

New York already had taken steps to establish a whale fishery for in December, 1652, the Directors of the Dutch West India Company wrote to Governor Stuyvesant at New York: "In regard to the whale fishery we understand that it might be taken in hand during some part of the year. If this could be done with advantage, it would be a very desirable matter, and make the trade there flourish and animate many people to try their good luck in that branch."15 Three years later the Council of New York "received the request of Hans Jough, soldier and tanner, asking for a tun of train-oil or some of the fat of the whale lately captured." At the town meeting held at Southam pton in the spring of 1672 an ordinance was adopted regulating the employment of Indians in the whale fishery, whereby "whosoever shall Hire an Indyan to go a-whaling, shall not give him for his Hire above one Trucking Cloath Coat, for each whale, he and his Company shall kill, or halfe the Blubber, without the Whale Bone."This was consented to by the Governor who also directed that "the like Rule shall be followed at East Hampton and other Places if they shall finde it practicable amongst them."The Governor also appointed a commission to visit Long Island and make strict inquiries among the English and also Indians concerning alleged abuses in the matter of drift whales. The inhabitants of Southampton at an early date found it desirable that all agreements "between the English and Indians relating to the killing of whales should be entered in the town books and signed by the parties in the presence of the clerk and certified by him. Boat-whaling was so generally practiced and was considered of so much importance by the whole community, that every man in the town of sufficient ability was obliged to take his turn in watching for whales from some elevated position on the beach, and to sound the alarm on one being seen near the coast."16

15 New York Colonial MSS. |

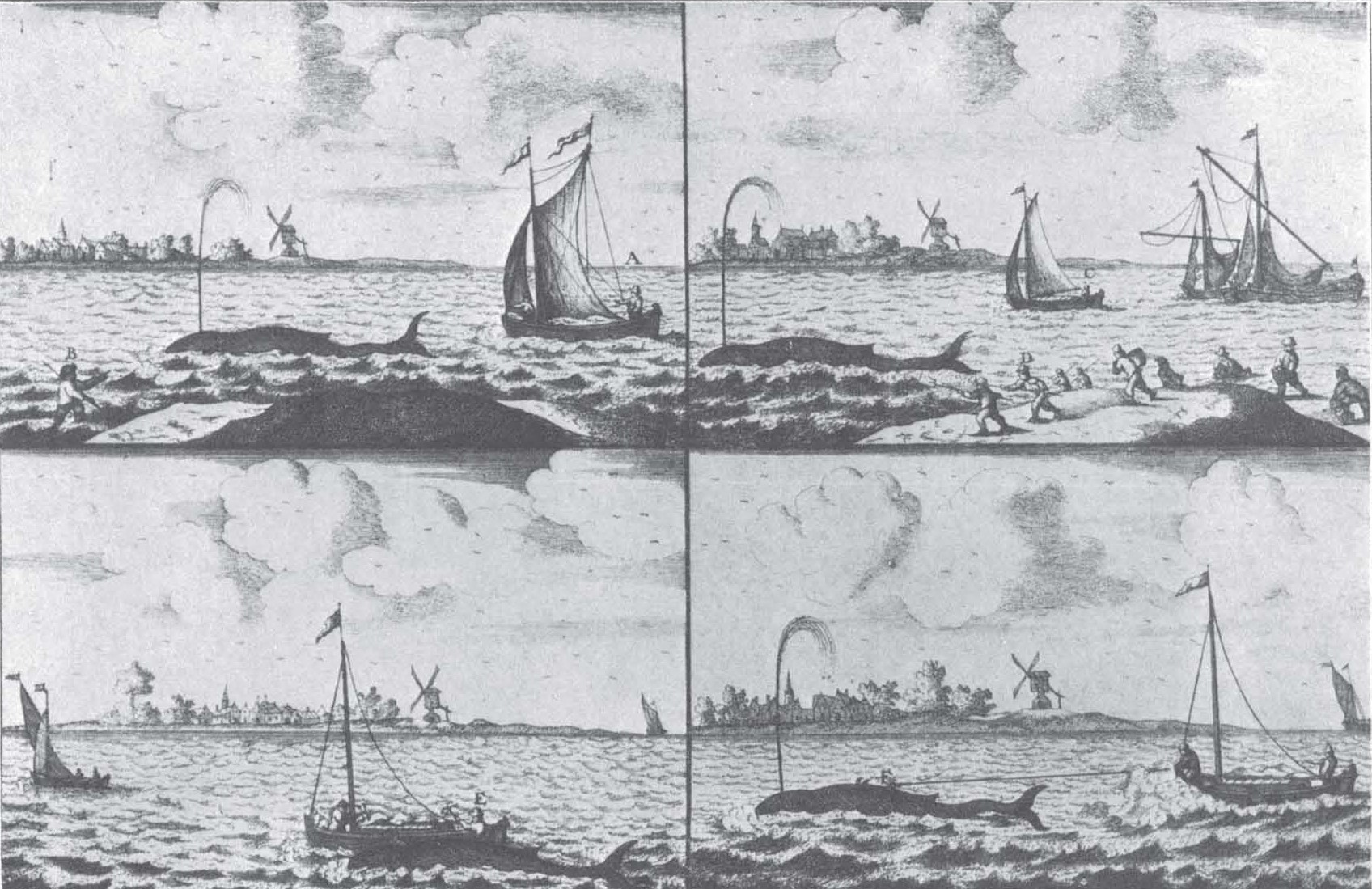

In April, 1668, an agreement was entered on the town records of Easthampton binding certain Indians of Montauket in the sum of £ 10 sterling, to go to sea a-whaling, on account of Jacobus Skallenger and others, beginning on the first of November and ending on the first of April, they engaging "to attend diligently with all opportunities for ye killing of whales or other fish, for ye sum of three shillings a day for every Indian, ye sayd Jacobus Skallenger and partners to furnish all necessarie craft and tackling convenient for ye design." Laws were enacted governing the operations of these whaling companies. A member of one company finding a dead whale killed by another company was obliged to notify the latter. The finder, however, must be rewarded. If the whale was found at sea, the finders and the killers were to share equally. If irons were found in the whale, they were to be restored to the owners. As time went on drift whales did not disappear but they became more scarce. As early as 1681, Andros reported that very few whales were driven on shore unless proved to have been struck by the fishermen. When the shores were well watched and boats patrolled the fishing grounds, there were few stranded whales. The boat fishery continued active until well into the eighteenth century. A memorandum kept by widow Martha Smith of St. George’s Manor, Long Island, records interesting details of the shore whaling in 1707. In January, "my company" killed a yearling whale that made twenty- seven barrels of oil. On February 4, Indian Harry from his own boat struck a whale but he failed to kill it, and Mrs. Smith’s boat was called to assist and the combined force gaining a victory. Mrs. Smith received a third of the oil amounting to four barrels. February 22, "my two boats and my son’s and Floyd’s boats" killed a yearling that produced thirty-six barrels. Her share was one half. "A school whale" yielded thirty-five barrels. In the month of June Mrs. Smith paid to the authorities in New York £ 15. 15s. as a tithe |

or tax, it being one twentieth part of her gains for the past season’s whaling.17 This tax imposed by the Royal Governors was an irritating grievance. Bellomont, in 1700, seized a whale found on the beach bearing the private marks of the person who had killed it and he impressed a man who was employed by the owner, to cut up the carcass. Lord Cornbury gave out that "the whale was a Royal fish," and would not permit whaling without a license. Governor Dongan seized all drift whales and Governor Dudley, in 1705, seized the whales taken by boats "under a Pretence of drift fish" and would not try the question at common law, but decided it in "the Admiralty." John Hull, the Boston mintmaster who made the "pine tree shillings," was also a merchant and shipowner. His diary shows how the trade in whale oil was conducted. In February, 1671, he records that "the men of Long Island, this winter, made a hundred or two tuns of oil of whales that they there kill."Boston became the commercial port for this industry and it seems probable that Hull was active in introducing the trade. In 1675 he sent his ketch "Sea- flower," Capt. John Harris, to Long Island, and in his "instructions" he ordered the captain to stow his whale oil with great care and to fill all the chinks in the cargo with bone of large size. The vessel was partly loaded in Boston with a miscellaneous cargo, which was to be sold at Long Island or returned by a chance vessel. The captain was to sell the oil and bone in England and then, if current prices permitted, he was to take up exchange on France and load there with "good salts."Harris was allowed some discretion, however, in the event that "the Lord’s providence shall discover any bettr improvement of yor ketch which wee Cannot foresee."If, after advising with specified correspondents in England, a direct return seemed more feasible, the "Seaflower" was to bring back bulky goods like "course wicker flasketts, allom, Coppress, drum rims, head 17 Thompson, History of Long Island, I, p. 438. |

snares, shod shovells, window glass" etc. If a part of the freight proceeds was to be returned, while the vessel went to France, it was to be invested in more valuable and lighter goods, like "black Ducape and Lutestringe."The voyage was in joint account with other partners and the Lord was to be enlisted, not in mere form, but as an active co-worker. "That hee may please to take the Conduct of you, wee pray you looke carefully that hee bee worshipped dayly in yor shipp, his Sabbaths Sanctifiede & all Sin and prophainess let bee supressed."18 The principal products of the Colonies at that time were whale and fish oil, whalebone, furs, deer, elk and bear skins for the markets of Spain, Portugal, and the Straits; and refuse fish, lumber, horses and provisions supplied to the West Indies. In 1690, Massachusetts Colony made two shipments of whale oil to London, 144 barrels and 152 barrels, for account of the Treasury. A cargo from Boston to Amsterdam included 748 barrels of oil "of New England fishing." Sperm whales seldom, if ever, came upon the shores of New England. They carry in their clumsy heads spermaceti, the best material for an illuminating candle, aside from wax, and their blubber yields an illuminating fluid much superior to the oil of the right whale. Sperm oil is also one of the very best lubricants known today. The earliest mention that has been found in New England records of a sperm whaling voyage exists in the Massachusetts Archives. In August, 1688, the commander of the brigantine "Happy Return," petitioned Governor Andros for "License and Permission, with one Equipage Consisting in twelve marines, twelve whalemen and six Divers – from this Port, upon a fishing design about the Bohames Islands, and Cap florida, for sperma Coeti whales and Racks: and so to return to this Port."Whether this voyage was ever undertaken we do not know. Wrecks on the Florida coast and in the West Indies may have proved to be a better paying proposition than whaling, but the 18 Hull Letter Book, American Antiquarian Society. |

petition is conclusive evidence that there were men in the Colony at that time familiar with the haunts of the sperm whale and with his capture. The first sperm whale of which Nantucket had actual knowledge "was found dead, and ashore, on the southwest part of the island. It caused considerable excitement, some demanding a part of the prize under one pretence, some under another, and all were anxious to behold so strange an animal. There were so many claimants of the prize that it was difficult to determine to whom it should belong. The natives claimed the whale because they found it; the whites, to whom the natives made known their discovery, claimed it by a right comprehended, as they affirmed, in the purchase of the island; an officer of the Crown made his claim, and pretended to seize the fish in the name of His Majesty, as being property without any particular owner. ... It was finally settled that the white inhabitants who first found the whale should share the prize equally amongst themselves. The teeth, considered very valuable, had been prudently taken care of by a white man and an Indian before the discovery was made public. The decision in regard to ownership certainly justified their precaution. This compromise made, the whale was cut up and the oil extracted. What the amount of it was is unknown. The sperm produced from the head was thought to be of great value for medical purposes. It was used both as an internal and an external application and such was the credulity of the people that they considered it a certain cure for all diseases; it was sought with avidity, and, for a while, was esteemed to be worth its weight in silver."19 The first sperm whale taken by a New England whaleman is supposed to have been captured in 1712 by Christopher Hussey of Nantucket, and the taking was the result of accident. He was cruising near the shore for right whales and was blown off shore for some distance by a strong northerly wind, where he fell in 19 Macy, History of Nantucket. |

with a school of sperm whales and killed one and brought its blubber home. This gave new life to the whaling business and several small vessels of about thirty tons burthen began to whale out "in the deep," as it was then called, to distinguish it from shore whaling. They fitted out for cruises of about six weeks, carried a few hogsheads, enough to contain the blubber of one whale, and after making a capture returned home to try out the oil. In 1715, Nantucket had six sloops engaged in this fishery, averaging thirty-eight tons and producing oil and bone to the value of £ 11000 sterling, the shore fishery, in the meantime, being still continued.20 The island of Nantucket is always associated with the whaling industry in New England, but its beginnings are a matter of tradition rather than recorded fact. The first Englishman to settle there was Thomas Macy who removed from Salisbury in the Massachusetts Bay in 1659. Soon after came Starbuck, Coffin and others, names famous in the history of Nantucket and of the whaling industry. Macy, the historian of the island, relates that soon after the settlement "a whale of the kind called ’scragg’ came into the harbor and continued there three days. This excited the curiosity of the people and led them to devise measures to prevent its return out of the harbor. They accordingly invented and caused to be wrought for them a harpoon, with which they attacked and killed the whale. This first success encouraged them to undertake whaling as a permanent business; whales being at that time numerous in the vicinity of the shores." In 1672, an effort was made by the islanders to induce one James Loper, who lived on the eastern end of Long Island, and afterwards at Martha’s Vineyard, and carried on whaling, to come to Nantucket and "carrey on a Designe of Whale Catching," the islanders to receive one third of the profits. He was to have a monopoly of the business for two years and ten acres of land and commonage rights. John Savidge, a cooper, was also 20 Macy, History of Nantucket. |

granted land as an inducement to remove to the island and set up his trade, "as the Town or Whale Company have need to employ him."For some reason the project fell through for it does not appear that Loper ever lived on Nantucket. But Savidge did and doubtless shore whaling, carried on in a small way, supplied him with employment. In 1690, further effort was made to enlarge the industry. On learning that "the people of Cape Cod had made greater proficiency in the art of whale- catching than themselves," they sent a committee to the mainland and induced Ichabod Paddock of Barnstable, to come to Nantucket and instruct them in the best method for killing whales and obtaining the oil. He proved himself an able instructor to so receptive a people, judging from the successful development of the industry in after years. Martha’s Vineyard, nearer the mainland, was settled before Nantucket and whaling began there at some time before 1652 when the town records mention the appointment of Thomas Daggett and William Weeks as "whale cutters for this year."At the town meeting held the next spring it was voted that drift whales were "to be cut out freely, four men at one time, and four at another, and so every whale, beginning at the east end of the town."Whale cutters were appointed each year thereafter and the industry flourished. An interesting dispute arose here, in 1692, concerning a whale cast on shore which was claimed by the agents of the proprietors and also by "John Steel, harpooner, on a whale design, as being killed by him."Much debate ensued and in order to save the oil it was agreed that the agents of the proprietors should cut up the whale and try out the oil "and that no distribution be made of the said whale, or effects, till after fifteen days are expired after the date hereof, that so such persons who may pretend an interest or claim in the whale, may make their challenge; and in case such challenge appear sufficient to them, then they may deliver the said whale or oyl to the challenger; otherwise to give notice |

to the proprietors, who may do as the matter may require."James Loper, of the Vineyard, petitioned the Colonial government of Massachusetts, in 1688, for a patent for making oil and in the petition represented that he had been engaged in the whale fishery for twenty-two years.21 In 1692, John Higginson and Timothy Lindall, shipowners and merchants living in Salem, wrote: "We have been jointly concerned in several whale voyages to Cape Cod, and have sustained great wrong and injury by the injust dealing of the inhabitants of those parts, especially in two instances: ye first was when Woodbury and company, in our boates, in the winter of 1690, killed a large whale in Cape Cod harbour. She sank and after rose, went to sea with a harpoon, warp, etc. of ours, which have been in the hands of Nicholas Eldridge. The second case is this last winter, 1691. William Edds and company, in one of our boats, struck a whale which came ashore dead, and by ye evidence of the people of Cape Cod was the very whale they killed. The whale was taken away by Thomas Smith, of Eastham, and unjustly detained."22 Ten years later Higginson wrote that he had "a considerable quantitie of whale oil and bone" ready for exportation and in 1706 he wrote to a friend in Ipswich of being concerned, with others, in boats for catching whales. The whaling industry on the island of Nantucket grew rapidly in importance after 1700. The Gulf Stream makes its nearest approach to the New England coast off Nantucket and whales were plentiful without going out of sight of land. The south side of the island was divided into four equal parts and to each part was assigned a company of six men who carried on the whaling business in common. Each division covered about three and a half miles of shore line and in the middle of a division a mast was erected with a look-out at the top and near by was built a

21 Felt, History of Salem, II, p. 223. |

hut in which the men lived. In clear weather one of the company was always in the look-out carefully scanning the sea for a sight of a spouting whale, and when seen, the boat was launched at once and the chase began. 23 A capture made, the whale was towed ashore and the blubber stripped off in the same manner well-known at a later date. Try-works were erected on the beach and the blubber, after being sliced and minced, was "tryed out" and the oil barrelled for later shipment to Boston. After shore fishing became unprofitable these try-works still continued in use, for in the off-shore fishery, carried on in sloops and small vessels, the blubber would be cut up and stowed in hogsheads on board and brought home there to be tried out and the oil extracted. Much the same method was followed all along the New England coast where whaling was carried on. At Nantucket, Indians were largely employed in the whale fishery, each boat’s crew being manned in part and sometimes wholly by Indians – and at a later date, in the palmy days of deep-sea whaling, ships usually had one or more Indians aboard – frequently expert harpooners. The first settlers at Nantucket located themselves at the western end of the island, but as the fishery increased in importance and vessels were used it became necessary to select a better site and the location where the town now stands was determined upon and here wharves were built and new houses erected. It was the custom in winter to haul the vessels and boats on shore as a measure of protection. Boats were placed bottom upwards and lashed together and equipment was carefully stored in warehouses. Each small vessel carried two boats, one of which was held in reserve in case of accident. The earliest recorded loss of a Nantucket whaling vessel is in 1722 when a sloop commanded by Elisha Coffin was lost at sea with all on board. Dinah, the widow of the master, in 1724 peti- 23 Crevecoeur, in his Letters of an American Farmer, writes that when whales were sighted off Southampton, the alarm was sounded by means of a horn, when the waiting boats would be hastily manned in pursuit. |

tioned the Great and General Court for legislation permitting her to marry again and in her petition she recites that "her Husband, Elisha Coffin did on the Twenty Seventh Day of April Annoq Dom: 1722 Sail from sd Island of Nantucket in a sloop: on a whaling trip intending to return in a month or six weeks at most, And Instantly a hard & dismall Storm followed; which in all probability Swallowed him and those with him up ; for they were never heard of."24 In 1731, a sloop, commanded by Thomas Hathaway, was lost and in 1742 another sloop, Daniel Paddock, master, went down with all on board. A local historian writing in 1792, of the shore fishery, relates that "it happened once, when there were about thirty boats about six miles from the shore, that the wind came round to the northward, and blew with great violence, attended with snow. The men all rowed hard, but made but little headway. In one of the boats there were four Indians and two white men. An old Indian in the head of the boat, preceiving that the crew began to be disheartened, spake out loud in his own tongue and said, Momadichchator auqua sarshkee Sarnkee pinchee eyoo sememoochkee chaquanks wihchee pinchee eyoo: which in English is, Pull ahead with courage: do not be disheartened; we shall not be lost now; there are too many Englishmen to be lost now. His speaking in this manner gave the crew new courage. They soon preceived that they made headway; and after long rowing, they all got safe on shore."25 The importance of the Indian in the New England whale fishery had long been recognized and in 1709, by Act of Parliament for the "Encouragement of Whaling," it was provided that any Indian bound to go to sea whale fishing, between November first and April fifteenth following, should not be arrested or kept out of employment under any pretence of a contract or debt; and if any one should suffer an Indian to drink liquor during the

24 Mass. Archives, IX, folio 181. |

time when he should be at sea or at work in connection with the whale fishery, should forfeit the sum of thirty shillings. This Act was in force in 1726 and perhaps later. The growth of the whaling industry brought about a material increase in the size and number of the vessels employed. Sloops and schooners of forty to sixty tons burthen began to cruise to the southward, remaining on that ground until July when they would return and refit and then go out for another cruise to the eastward of the Grand Bank. It soon came about that Nantucket could not furnish men enough to man the fleet and Cape Cod and Long Island were called upon to make up the deficiency. The large production of oil naturally glutted the colonial market and forced prices down, so that the Nantucket whalers began to think of a direct contact with the foreign markets. Since the beginnings of the industry Boston merchants had acted as factors for the New England whalemen and had furnished them with needed supplies. The principal foreign market for the New England trade was London, but Amsterdam and other ports on the continent claimed a share. A mixed cargo from Boston direct to Amsterdam included 748 barrels of oil "of New England fishing."26 As early as 1720, Nantucket made a direct shipment to the London market and the bill of lading has been preserved.27 Its quaint phrase still possesses an interest for the descendants of old-time sailors and shipowners and those who love the sea.

26 Mass. Archives, LXII, folio 69. |

"It was found," says Macy,28 "that Nantucket had in many places become famed for whaling, and particularly so in England, where partial supplies of oil had been received through the medium of the Boston trade. The people, finding that merchants in Boston were making a good profit by first purchasing oil at Nantucket, then ordering it to Boston, and thence shipping it to London, determined to secure the advantages of the trade to themselves, by exporting their oil in their own vessels. They had good prospects of success in this undertaking, yet, it being a new one, they moved with great caution, for they knew that a small disappointment would lead to embarrassments that would, in the end, prove distressing. They, therefore, loaded and sent out one vessel, about the year 1745. The result of this small beginning proved profitable and encouraged them to increase their shipments by sending out other vessels. They found, in addition to the profits on the sales, that the articles in return were such as their business required, viz: iron, hardware, hemp, sail cloth, 28 Macy, History of Nantucket, p. 51. |

and many other goods, and at a much cheaper rate than they had hitherto been subjected to." The consumption of oil in lamps and also in the manufactures increased about this time and was a great encouragement to the whale fishery; in fact, cod and whale products were the principal exports to Great Britain from Massachusetts. But this prosperity was not long to continue. As a result of the great public expenditures in connection with the wars with the French, resulting in the conquest of Canada, Parliament looked about for new sources of revenue and in 1761 a duty was imposed on all oil and bone carried into England from the colonies. By another Act it became unlawful for a colonial vessel to find any other market and at the same time a bounty was allowed to British whalers. This unjust discrimination soon resulted in petitions to Parliament from New England merchants and London firms engaged in the colonial trade. They represented that "in the Year 1761, The Province of the Massachusetts Bay, fitted out from Boston and other ports ten vessels of from Seventy to Ninety Tons Burden for this Purpose. That the Success of these was such as to encourage the Sending out of fifty Vessels in the Year 1762 for The same trade, That in the year 1763 more than Eighty Vessels were imploy’ d in the same manner.29 That they had already imported to London up- 29 Out of Nantucket there’s Whalemen seventy-five, But two poor Worths among them doth survive: There is two Ramsdills & there’s Woodbury’s two, Two Ways there is, chuse which one pleaseth you, Folgers thirteen, & Barnards there are four, Bunkers there is three & Jenkinses no more. Gardners there is seven, Husseys there are two, Pinkhams there is five and a poor Delano. Myricks there is three & Coffins there are six, Swains there are four and one poor gally Fitch. One Chadwick, Coggshall, Coleman there’s but one, Brown, Baxter, two & Paddacks there is three, Wyer, Stanton, Starbuck, Moores is four you see, But if for a Voyage I was to choose a Stanton, I would leave Sammy out & choose Ben Stratton, And not forget the Bocott is alive, And that long-crotch makes up the seventy-five. This is answering to the list, you see, Made up in seventeen hundred & sixty-three. Whale list of Nantucket captains by Thomas Worth, 1763. |

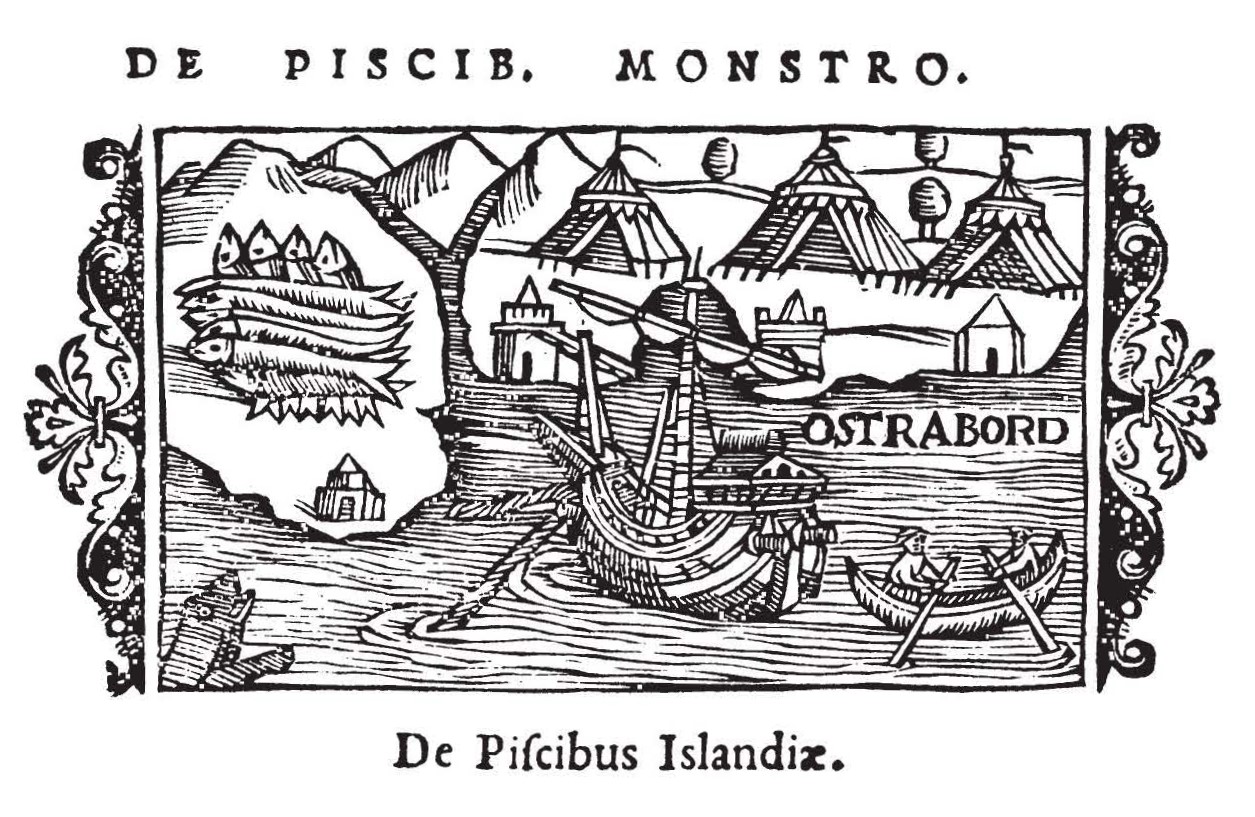

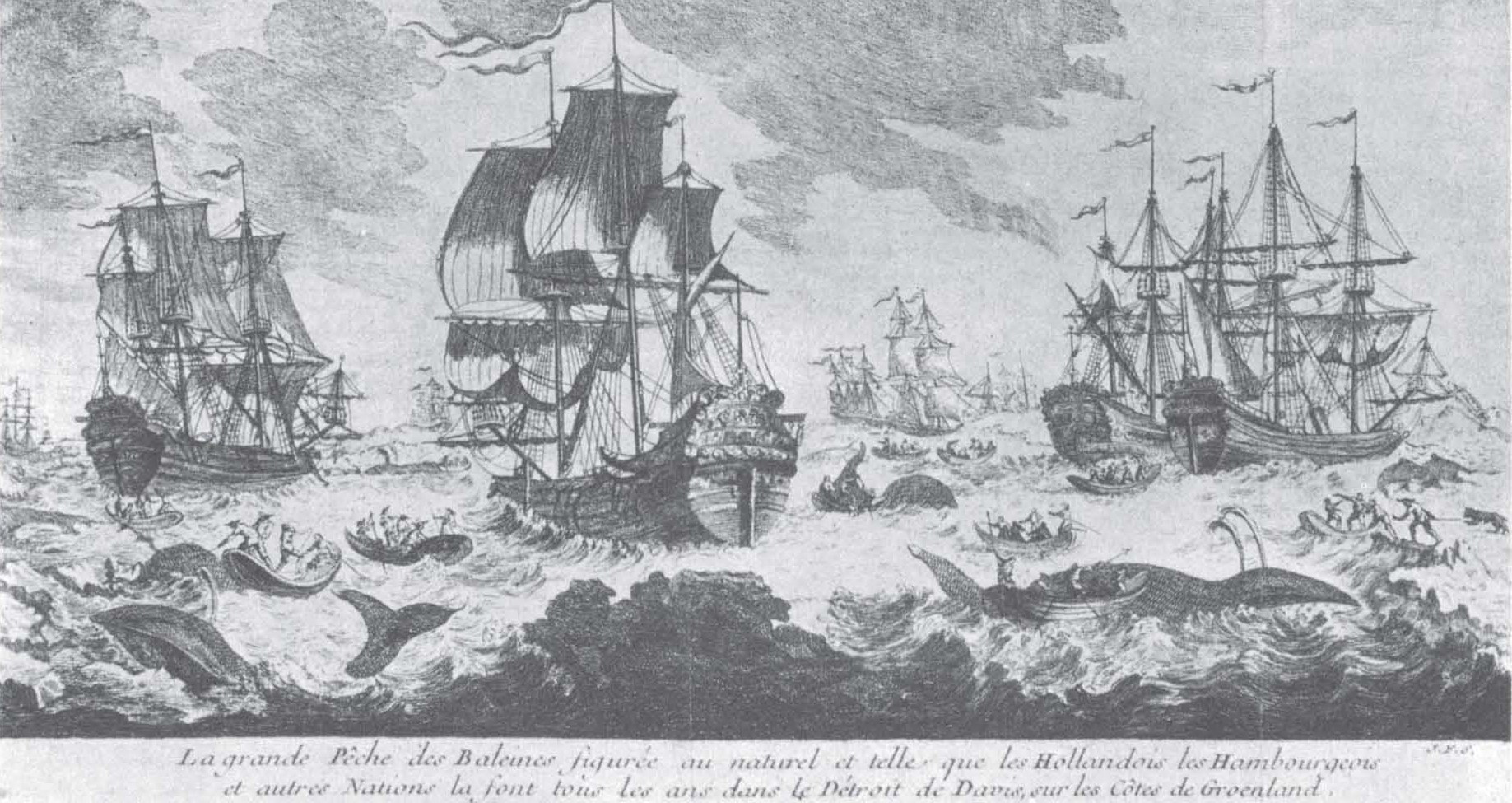

wards of 40 ton of Whale Finn; being the produce of the two first years. That upon Entring of the above Finn, a Duty was required and paid upon it, of thirty-one Pound, ten shillings per Ton. That the weight of this Duty was render’d much heavier by the great reduction made in the price of Dutch Bone since the commencement of this Trade from £500 to £300 per Ton."30 The petition further represents that the reason for conferring the bounties on British vessels was to encourage the fishery to compete with the Dutch, yet, notwithstanding, not enough oil and bone was being brought into the English market by British vessels to supply the demand.31 It naturally followed that the American whale fishery was soon relieved of the discriminating duty. In 1768, Nantucket sent out eighty vessels with an average burden of seventy-five tons and probably as many more went out from other New England ports – Cape Cod, Falmouth, Dartmouth (now New Bedford), Boston, Providence, Newport, Warren and other ports engaged in the fishery to a lesser extent. These vessels sailed for Davis Straits, the Straits of Belle Isle, the Grand Banks, Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Western Islands. The Davis Straits and northern fishery was visited by New England whalers as early as 1732, when Captain Atkins brought to Boston a Greenland bear. He went as far as 66° north. In the spring of 1737 there were a number of clearances from Boston for Davis Straits. In July, 1737, Capt. Atherton Hough took a whale "in the Straits" and two years later the August 2d issue of the Boston News-Letter states: "There is good Prospect of Success in the Whale Fishery to Greenland this Year, for several vessels are come in already, deeply laden, and others expected."

30 Massachusetts Archives, Vol. LXVI, folio 243. |

The New England Journal of April 19, 1737, says of Provincetown, Mass.: "There are now fitting out from this Place a dozen sail of vessels (and some of them burthen’ d a Hundred Tons) bound for Davis Straights on the Whaling Design and are just ready to sail. So many of our People are now bound on this Voyage, that there will not be left behind above a Dozen or Fourteen men in the Town." In 1748, Parliament passed an Act to encourage this fishery which had languished because of the war with France. A bounty of twenty shillings a ton was granted to ships engaged in whaling during the existing war and harpooners and whalemen engaged in the Greenland fishery were exempted from impressment. All whalers must remain in the Davis Straits from May until August 20th unless sooner full of oil or obliged to return by accident. In 1761, after the conquest of Canada, the New England whalemen reaped a rich harvest in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Straits of Belle Isle. The Boston News-Letter for Aug. 8, 1765, has the following: "Tuesday one of the sloops which has been on the Whaling Business returned here. We hear that the Vessels employed in the Whale Fishery from this and the neighbouring Maritime Towns, amounting to near 100 sail, have been very successful this Season in the Gulph of St. Lawrence and Streights of Belle Isle; having tis said, already made upwards of 9,000 Barrels of Oil."Two weeks later the News-Letter reported that news had been received from the whaling fleet on the Labrador coast and that the vessels were in difficulties in consequence of orders issued by the captain of His Majesty’s sloop "Zephyr," stationed on that coast, who had decreed that refuse parts of whales must be left at least three leagues from the shore to prevent damage to the cod and seal fishery; that no trade or intercourse might be carried on with the French; that the Indians must be treated with the greatest civility and on no account were they to be supplied with spirituous liquors; that no passengers could be trans- |

ported to the Plantations and no other fishing might be carried on than whaling. It was this last regulation that fell most heavily on the New England whalemen who were accustomed to go north prepared for either the cod or the whale fishing. If whales were scarce then the cod lines were used. It is not surprising that the News-Letter records that "Since our last, several Vessels are returned from the Whaling Business, who have not only had very bad Success, but also have been ill-treated by some of the Cruisers on the Labradore Coast."This regulation controlling the cod fishery was inforced under a pretense that the coast had been patented to a Company by the Governor of Newfoundland and Labrador. In consequence of these orders and the strict supervision of the King’s ships on the Labrador Station, many of the whaling fleet left the coast and went to the banks. The year 1766 proved to be a poor season for the northern whale fishery. Under date of Oct. 2, 1766, the Boston News-Letter says: "Since our last a Number of Vessels have arrived from Whaling. They have not been successful generally. One of them, viz: Capt. Clark, on Thursday Morning last discovered a Spermaceti Whale near George’s Banks, mann’d his Boat and gave Chase to her, and she coming up with her jaws against the Bow of the Boat struck it with such violence that it threw a Son of the Captain; (who was forward ready with his Lance) a considerable Height from the Boat, and when he fell the Whale turned with her devouring Jaws opened, and caught him. He was heard to scream, when she closed her Jaws, and part of his Body was seen out of her mouth, when she turned and went off." One of the results of the restrictions enforced on the Straits of Belle Isle whaling ground was the sending out of whaling ventures to the Western Islands, the Cape de Verdes and the banks off the Brazilian coast. Nearly fifty New England whalers went to these southern latitudes during the year 1767. Whales at that |

time were also pursued along the edge of the Gulf Stream and there they continued to be found for many years. The following year found many whalers again on the Labrador coast as a result of a report, current in New England, that the irksome regulations had been revoked. The last of April, 1768, saw about sixty whalers anchored in Man-of-War Cove, Canso Gut, surrounded with drift ice. On May 23d they were still there and that day cleared their decks of snow which was "almost over shoes deep." In addition to the normal dangers of the whale fishery, there were times when the whalemen were in danger of capture by privateers and even pirates. The French and Spanish privateers were on the New England coast in 1741 and in May a whaling vessel out of Barnstable, commanded by Capt. Solomon Sturgis, was captured. The captain and eight hands were dismissed, but John Davis, the mate, and four men were carried off in the sloop. The frequency of privateers seems to have prevented the sending out of whalers to the Davis Straits, for the Boston newspapers report no departures or arrivals from that ground for several years. A French privateer made several captures in 1744 near Nantucket and in Vineyard Sound and landed many of her prisoners on the Island. During the years 1755 and 1756, six Nantucket whalers were lost at sea and six were taken by the French and destroyed, the crews being carried away into captivity. In 1768, eighty whalers sailed from Nantucket but only seventy returned. The missing ten were either captured by the French or lost at sea and this ratio of disaster seems to have prevailed elsewhere. The Boston News-Letter preserves an account of an adventure that happened to two Nantucket whaling sloops while lying at anchor in the harbor of Abaco, one of the Bahama Islands. A ship appeared off the mouth of the harbor with her signals set asking for assistance. One of the whaling captains at once made up a boat’s crew and rowed out to the ship. On reaching the |

vessel’s side and boarding her, he was surprised to have a pistol presented to his head by the officer in command with a demand that he should pilot the ship into the harbor. Nothing else was to be done and soon the ship was at anchor where a point of land lay between her and the sloops. This done, the boat was dismissed and the men returned to their vessels. The Nantucket captains now held a consultation as to what course should be pursued. As those who had been on board the stranger noticed that the men seemed to be armed and that a man was alone in the cabin, it was concluded that the ship was in the hands of pirates and that the man in the cabin was the former captain. Measures were immediately taken to secure the vessel and crew. An invitation was extended to the usurping captain, his officers and passengers, to dine on board one of the sloops and this was accepted. At the appointed time the supposed pirate captain, his boatswain and the man seen in the cabin, as representative of the passengers, came on board the sloop. As the dinner progressed the supposed pirate became uneasy and proposed to return to his vessel, whereupon he was at once seized by the whalemen and bound. The passenger, who was in fact the actual captain, as had been supposed, then related what had happened. The ship had sailed from Bristol, R. I., bound for the coast of Africa on a slaving voyage. The slaves had been landed in the West Indies and a return cargo of sugar had been taken aboard, and not long after this a mutiny occurred, the mutineers intending to become pirates, a business at that time quite thrifty and promising. The whalemen now told the boatswain, who had come aboard with the pirate captain, if he would go on board the ship and return with the former mate, who was in irons, and also aid in recapturing the vessel, they would use their best endeavors to have him cleared from the penalties of the law. They also prudently intimated to him that there was a man-of-war within two hours |

sail from which they could obtain assistance, and he was told that they would set a certain signal when they had secured help from the ship of war. The boatswain not returning according to agreement, one of the sloops weighed anchor and stood toward the pirate as though to pass on one side of her. As she approached, the mutineers shifted their guns over to the side on which it seemed apparent she would pass and trained them so as to sink her as she sailed by. But the whalemen on the sloop were alive to their intentions and as she neared the ship her course was suddenly changed and she swept by on the other side and was out of range of the guns before the pirates could reshift and train their cannon. The sloop continued on her course until she was out of sight of the ship. She then tacked, set the signal agreed with the boatswain that help had been secured from the man-of-war, and returning steered boldly for the ship. As she hove in sight, the pirates, recognizing the signal and believing an armed force from the man-of-war was on board, abandoned the ship and made for the shore in their boats where, not long after, they were run down and taken into custody. The whalemen boarded their prize, released the mate, and brought the ship into New Providence where a bounty of $2500. was allowed them. As for the would-be pirate captain – he was hanged. Whalemen were in danger of capture by pirates not only to the southward, near the West Indies, but also in home waters, almost within sight of their own anchorages. Early in the eighteenth century piracy was common everywhere, and with the coming of spring the pirate captains, who had remained in the warm waters of the West Indies during the winter months, would cruise northward along the coast capturing small vessels in the hope of obtaining provisions and also looting larger craft bound to and from Europe or the Leeward Islands. Between 1722 and 1724, one of the most dreaded of these pirates was Capt. Ned Low, a bloodthirsty scoundrel who had |

lived in Boston for some years, where he married a respectable girl and had children. He was a rigger by trade and having been discharged by his employer shipped on a sloop bound for the Bay of Honduras for a cargo of logwood. While there he became a pirate and meeting with success he soon became captain of a sloop and later commanded a well-manned ship. Within twenty months he took one hundred and forty vessels. On June 10th, 1723, Low, in the sloop "Fortune," was off the eastern end of Long Island with his consort, the sloop "Ranger," when the man-of-war "Greyhound," of 20 guns and 120 men, on the New York Station, came in sight and after a two hours’ fight captured the "Ranger" and took thirty-seven whites and six negroes into Newport, where the captain and twenty-five of his men were hanged on gallows set up between high and low water mark. When Low saw that his consort could not escape, he showed the real stuff that he was made of and bore away leaving the "Ranger" to her fate. But his rage and chagrin knew no bounds and swearing many oaths he vowed vengeance on the unfortunates that next fell into his hands. This happened only two days later when he came upon a sloop out of Nantucket that was whale fishing about eighty miles off shore. She had two whaleboats and one of them fortunately was out and at some considerable distance from the sloop at the time she was taken. The men in this boat, seeing what had happened, got safely to another whaling sloop some distance away and all escaped. The captain of the captured sloop was Nathan Skiff, a young unmarried man living on Nantucket. Low first ordered him stripped and then cruelly whipped him about the deck. His ears were then slashed off. After a time they grew tired of beating the unfortunate man and telling him that because he had been a good captain he should have an easy death, at last they shot him through the head and sunk the sloop. Low "forced" a boy and two Indians and allowed three others of the crew to go away |

in a whaleboat in which, fortunately, there was a little water and a few biscuits, and with good weather these men at last reached Nantucket safely – "beyond all expectation," ends the account in the Boston News-Letter. Low’s insane rage was unabated two days later when a fishing boat was taken off Block Island. The master was dragged on board the pirate sloop and Low with furious oaths at once attacked the unfortunate man with a cutlass and hacked off his head. He gave the boat to two Indians who sailed with the murdered man and sent them away with the information that he intended to kill the master of every New England vessel he captured. On the afternoon of the same day two whaling sloops out of Plymouth were taken near the Rhode Island shore. The master of one vessel he ripped open alive and taking out the poor man’s heart ordered it roasted and then compelled the mate to eat it. The master of the other sloop he slashed and mauled about the deck and then cut off his ears and had them roasted and after sprinkling with salt and pepper, made the unfortunate man eat them. His wounds were so severe that he afterwards died.32 Low proposed to murder some of the hands on these whaling sloops but the pirate crew had had enough blood about the deck for one day and swore the rest of the men should go free so Low was obliged to submit. These men brought home the information that the pirate master and crew claimed to have on board nearly £ 150,000 value in gold and silver coin and plate.33 By the middle of the eighteenth century the increased use of lamps made whale oil a necessity. In 1742 it sold in the English market at £ 18.0.13 per tun and ten years later it was bringing £21. In 1770, the American colonies were exporting 5667 tuns of whale oil, most of it going to England, valued at £83.012, while the production of bone that year amounted to 112,971 pounds valued at £ 19.121.

32 Boston News-Letter, June 27, 1723. |

John Adams, in his "Diary," records the substance of a conversation with William Pitt, in which he remarked to the English statesman that "the fat of the spermaceti-whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised that you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets, to the receiving, as a remittance, our spermaceti oil. The lamps around Grosvenor Square, I knew, and in Downing Street, too, I supposed, are dim by midnight, and extinguished by two o’clock; whereas our oil would burn bright till 9 o’clock in the morning."34 The town of Boston in New England supplied itself with street lights on March 2, 1773, when nearly three hundred lamps were lighted for the first time. "They will be of great utility to this metropolis," remarked the editor of the Massachusetts Gazette. At a much earlier date, however, public spirited persons in Boston had set lamps outside their houses, to light the narrow streets. In the early days many New England families made dipped candles, and a better grade was cast in moulds. Tallow candles were also manufactured in many of the larger towns and became an article of commerce early in the eighteenth century. In November, 1700, the town of Boston granted liberty to Capt. Nathaniel Byfield, Capt. Andrew Belcher and others, "to set up a furnace or kiddle for melting tallow in order to make candles." The manufacture of candles from sperm oil was projected in New England as early as 1749 when Benjamin Crabb of the town of Rehoboth petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for "the Sole priviledge of making Candles of Coarse Sperma Caeti Oyle."He represented that he had been at great expense in providing himself with proper implements and if duly encouraged he proposed to undertake the manufacture of sperm candles and to instruct others in the art. The Representatives enacted a bill 34 Works of John Adams, VIII, pp. 308-309. |

granting Crabb and his heirs sole rights for a term of fourteen years, which the Council amended by reducing the period to ten years, and requiring that Crabb should set up his works within seven miles of Boston. There was also a provision providing for enactment in case "no other Person in the Province has the Art of pressing, fluxing and chrystalizing of Sperma Ceti and course Sperma Ceti Oyle, and of making Candles of the same."35 Crabb did not accept the provisions of the special legislation enacted for his benefit and Macy in his "History of Nantucket" states that he removed to Rhode Island where he set up a works that was destroyed by fire within a short time. In 1753, Obadiah Brown erected a candle-works near Providence and Crabb was placed in charge of the manufactory. Crabb proved to be less capable than Brown supposed and the secret of refining was at last acquired by Brown as a result of his own experiments. Moses Lopez, a Jewish merchant at Newport, engaged in the same business in 1755 and was soon followed by others. In 1746 there arrived in Boston two young men from Devon, England – Joseph Palmer and Richard Cranch – who opened a wool-card manufactory, which was so successful that six years later they acquired a large tract of land in Braintree, in that part of Quincy known as Germantown, and built a chocolate mill and spermaceti and glass works. Josiah Quincy was also concerned in the spermaceti works and petitioned the General Court, Dec. 12, 1752, for the privilege of carrying on the candle manufactory under a new process stating that "a person lately from England, well skilled in the Art of Refining Sperma Caetia from the Oyle, and making the same into Candals, has applied to him for employment in the business, that he has invented a new Machine for the more easy expressing the Oyl from the Sperma as also sundry Utensils never before used to the great improvement of the manufacture." The person "lately from England" was one John Surah, and 35 Massachusetts Archives, Vol. LIX, folio 369. |

less than four months later he, too, petitioned the General Court, representing the "sundry Hardships he has suffered by the unjust Treatment of Mr Josiah Quincy, of Braintree, and as he is a Stranger in the Country, he prays the Intoposition and Protection of the Country."36 It is quite evident that the two men had fallen out over the project for making "Candals" from "Sperma Caetia." The manufacture continued, however, and turned out to be a business success. In November, 1761, the eight manufacturers of spermaceti candles located in New England, at the suggestion of Richard Cranch & Co., of Braintree, entered into an association under the name of "The United Company of Spermaceti Candlers," in order to control the manufacture. The agreement was to be in force for seventeen months.37 Orders were to be sent to buyers of head matter not to pay more than £ 6 per tun above the price of sperm body brown oil and the price for the latter was to be determined by the current price given by Boston merchants for the London market on the day the purchaser received the head matter. Agents buying the same were not to receive above 2-1/2 per cent commission. Spermaceti candles were not to be sold within the limits of New England at less than one shilling, ten pence, half penny per pound, with an extra charge of a shilling for each box, to contain about a quarter of a hundred weight. None of the parties to the agreement was allowed to take on any new partners without the consent of the other firms. In case it should come about that the price for head matter should remain above £6 per tun more than the price for oil, the association agreed to fit out at least twelve vessels to be employed in the whale fishery on joint account. They also agreed to use "all fair and honourable means to prevent the setting up by any other Spermaceti works." Those who engaged in this trust were Obadiah Browne & Co.,

36 Massachusetts House Journal. |

Providence, R. I. ; Richard Cranch & Co. and Edward Langdon & Co., Boston; Napthali Hart & Co., Isaac Stelle & Co., Thomas Robinson & Co., Aaron Lopez & Co., and Collins & Rivera, all of Newport. There also was a firm in Philadelphia whose name does not appear. Seven factors of the association were located at Nantucket, one at Newport, one at Providence and one at Boston.38 The process of manufacture was so carefully kept a secret that it was not until 1772 that the people of Nantucket were able to carry on the business there. The first candle house in New Bedford was built about the same time. As the years passed and the time drew near when the Colonies should test their strength with the Mother Country, the whaling business increased to an extent unimagined. In 1775 there were over three hundred and fifty New England vessels engaged in the whale fishery, some of them of large tonnage for the times. Other trades were interested in the success of the whalers – the rope-maker, the cooper, the blacksmith, the carpenter and those who worked at shipbuilding. While a ship was at sea the owners at home were occupied in procuring supplies and equipment needed for the next voyage and so a considerable number of persons became interested directly or indirectly in the success of the fishery. "The cooper, while employed in making the casks, took care that they were of sound and seasoned wood, lest they might leak his oil in the long voyage; the blacksmith forged his choicest iron in the shank of the harpoon, which he knew, perhaps from actual knowledge, would be put to the severest test in wrenching and twisting, as the whale, in which he had a one-hundredth interest, was secured; the rope-maker faithfully tested each yarn of the towline, to make certain that it would carry two hundred pounds’ strain, for he knew that one weak inch in his work might lose to him his share in a fighting monster. "39

38 Commerce of Rhode Island, Vol. I, pp. 80-92; 97-100. |