|

Charles M. Scammon, (1825-1911) |

|

|

Entered acording to Act of Congress, in the year eighteen hundred and seventy-two,

By CHARLES M. SCAMMON, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C.

JOHN H. CARMANY & CO., PRINTERS, |

|

THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF

LOUIS AGASSIZ. AS A HUMBLE TRIBUTE FROM THE AUTHOR. |

CONTENTS.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

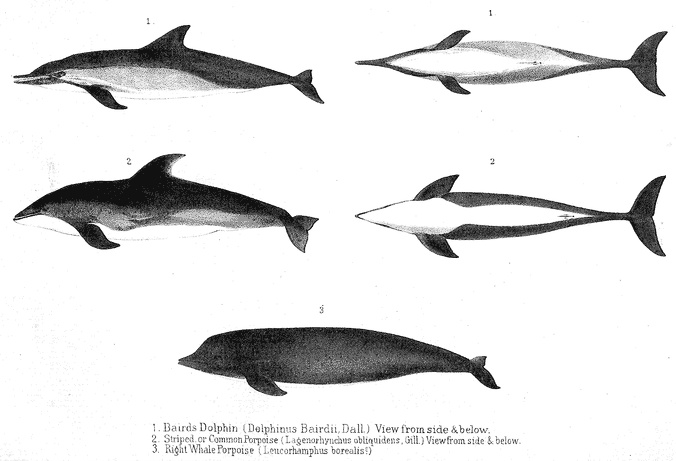

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

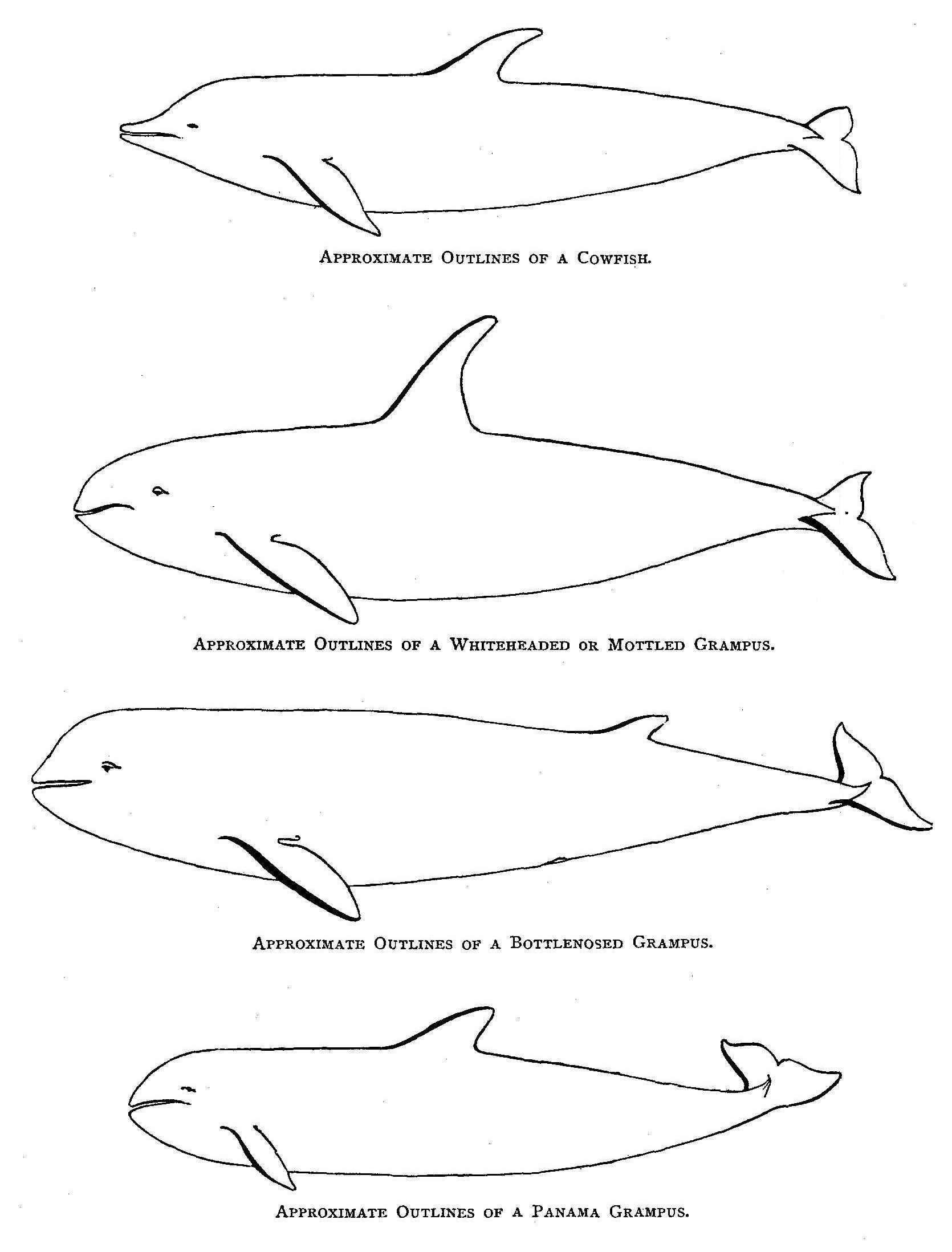

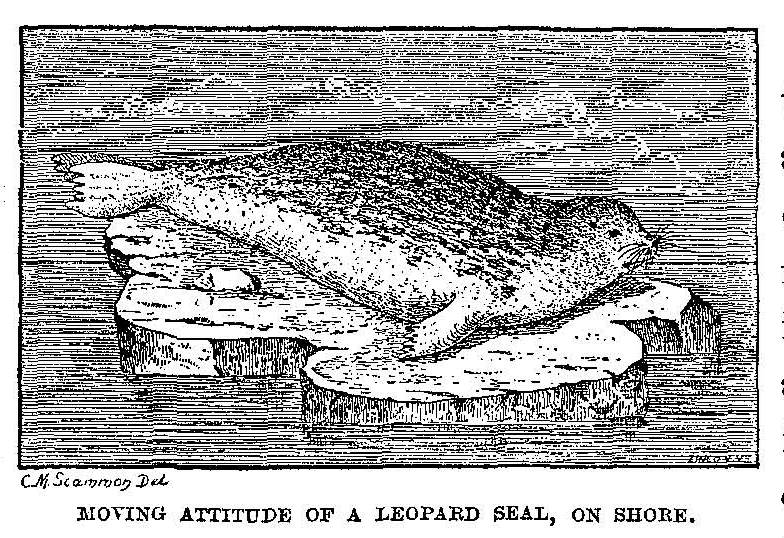

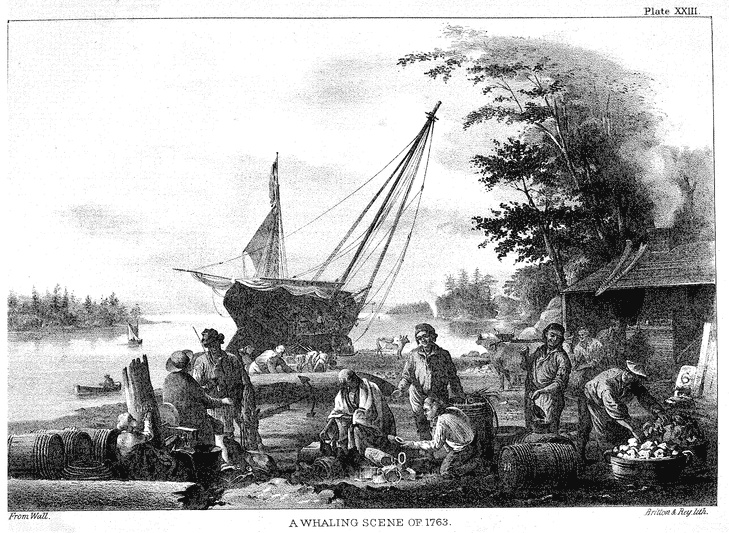

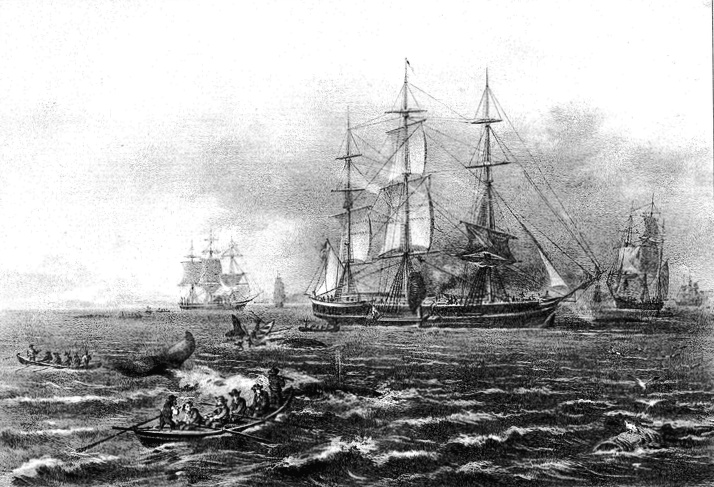

PREFACE.Being on the coast of California in 1852, when the "gold-fever" raged, the force of circumstances compelled me to take command of a brig, bound on a sealing, sea-elephant, and whaling voyage, or abandon sea-life, at least temporarily. The objects of our pursuit were found in great numbers, and the opportunities for studying their habits were so good, that I became greatly interested in collecting facts bearing upon the natural history of these animals. Reference to the few books devoted to the subject soon convinced me that I was at work in a department in which but little definite knowledge existed. This was true even of the whales, the best known of this class; and I was soon led to believe that, by diligent observation, I should be able to add materially to the scanty stock of information existing in regard to the marine mammals of the Pacific Coast. I was the more encouraged to pursue these investigations, because, among the great number of intelligent men in command of whaling-ships, there was no one who had contributed anything of importance to the natural history of the Cetaceans; while it was obvious that the opportunities offered for the study of their habits, to those practically engaged in the business of whaling, were greater than could possibly be enjoyed by persons not thus employed. The chief object in this work is to give as correct figures of the different species of marine mammals, found on the Pacific Coast of North America, as could be obtained from a careful study of them from life, and numerous measurements after death, made whenever practicable. It is also my aim to give as full an account of the habits of these animals as practicable, together with such facts in reference to their geographical distribution as have come to my knowledge. It is hardly necessary to say, that any person taking up the study of marine mammals, and especially the Cetaceans, enters a difficult field of research, since the |

opportunities for observing the habits of these animals under favorable conditions are but rare and brief. My own experience has proved that close observation for months, and even years, may be required before a single new fact in regard to their habits can be obtained. This has been particularly the case with the dolphins, while many of the characteristic actions of whales are so secretly performed that years of ordinary observation may be insufficient for their discovery. There is little difficulty in making satisfactory drawings of such smaller species of marine mammals as can be taken upon the deck of a vessel, but it is extremely difficult to delineate accurately the forms of the larger Cetaceans. When one of these animals is first captured, but a small part of its colossal form can be seen, as, usually, only a small portion of the middle section of the body is above the water; and when the process of decomposition has caused the animal to rise, so that the whole form is visible, it is swollen and quite distorted in shape. Again: these animals change their appearance in the most remarkable manner with every change of position, so that it is only from repeated measurements and sketches, and as the result of many comparisons, that I have been able to produce satisfactory illustrations of these monsters of the deep. I take occasion here to acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr. Rey, of the firm of Britton & Rey, lithographers, who laid aside his own business, as far as possible, in order that he might give his personal attention to the execution of nearly all the plates representing whales and seals. The remaining work of that description was put into the hands of Mr. Steinegger, the junior partner of the firm; his excellent sea and landscape backgrounds speak for themselves. Plain and simple language has been used in description. Where whaling terms have been employed, their definitions are indicated by reference marks, or may be found in the glossary contained in the Appendix. I desire to tender my sincere thanks to many personal friends and others, not only for literary, but also for financial aid; for, without the generous contributions of gentlemen of the Pacific Coast, and San Francisco especially, this work could not have made its appearance in its present form. To Professor J. D. Whitney, State Geologist of California, I wish particularly to acknowledge my indebtedness for his encouragement and untiring assistance in preparing this volume for the press. My thanks are also due to Professor S. F. |

Baird, of the Smithsonian Institution; Professor George Davidson, of the United States Coast Survey; Doctor W. O. Ayres, of San Francisco; Doctor Theodore Gill, of Washington; Mr. J. A. Allen, of Cambridge; Mr. R. E. C. Stearns, of San Francisco; Mr. Albert Bierstadt, of Irvington, N. Y.; Mr. W. H. Dall, of the Smithsonian Institution; and to Doctor George Hewston, of San Francisco, for special assistance. Also, to Mr. F. C. Sanford, of Nantucket, Mass.; Messrs. Williams and Chapel, of the firm of Williams, Havens & Co., New London, Conn.; and Dennis Wood, Esq., of New Bedford, for valuable statistics relative to the whale-fishery. It is with pleasure that I also mention the assistance I have received from officers of the United States Revenue Marine, in making scientific collections for the study of whales and seals, and in furnishing specimens for the National Museum at Washington. I would particularly mention Lieutenants George W. Bailey, W. C. Coulson, G. E. McConnell, and Engineers J. A. Doyle and H. Hassel. The account of the American Whale-fishery has been compiled from the most reliable sources within reach, and from the experience of many whalemen with whom I was associated for several years, while in active service on the principal whaling-grounds then frequented. I have also attempted to give a chronological account of the rise, progress, and decline of our great national maritime enterprise, the whale-fishery; and to make the picture complete, a few pages have been devoted to a description of the every-day life of a whaleman, his characteristic traits, and the incidents that make up the routine of a whaling-voyage. The "Catalogue of the Cetacea" appended to this work has been drawn up with great care by Mr. W. H. Dall, who has taken pains to do the work as thoroughly as circumstances would permit; and as I have assisted him with my personal knowledge of those species which are of rare occurrence on this coast, and placed in his hands all my notes and collections, I trust that his paper will be found of great assistance to the professional naturalist. As Mr. Dall remarks, however, "Completeness is not claimed for this list. In fact, it can hardly be attained for a considerable period, when the difficulties and expense connected with these researches are appreciated." Only two species of Cetaceans have been added to the list of those mentioned as not being represented by "material sufficient to indicate their zoological position;" and these were not known to Mr. Dall at the time he was preparing his list. |

The volume now presented to the public has been put together from materials which have accumulated during many years. At sea, when not occupied with official duties, amid calms and storms, I have devoted myself to its preparation; and it is hoped that the public may find in these results of prolonged labor something of the profit and pleasure with which the author has been rewarded while occupied in their collection and elaboration.

Charles M. Scammon.

San Francisco, May, 1874.

|

PART I.CETACEA |

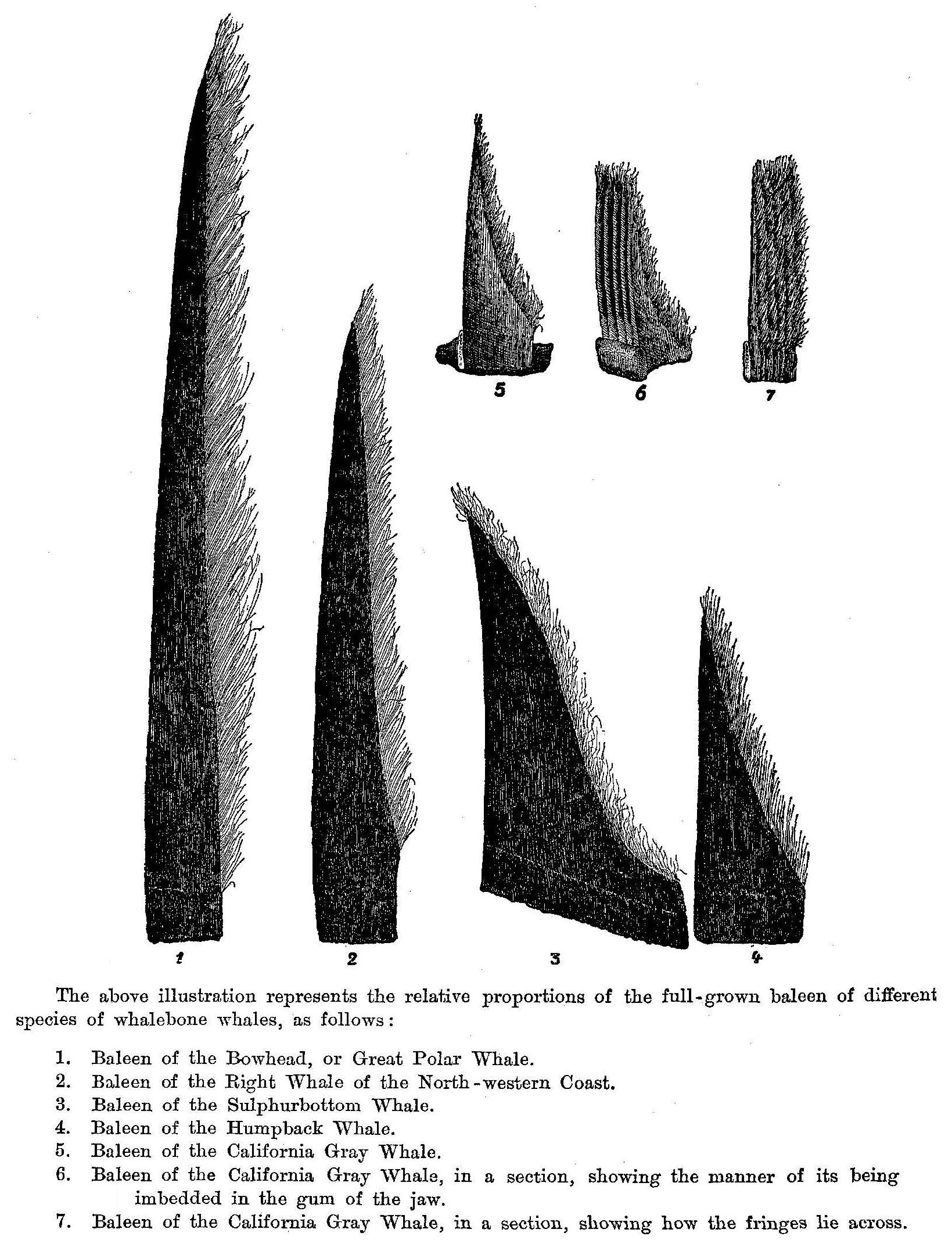

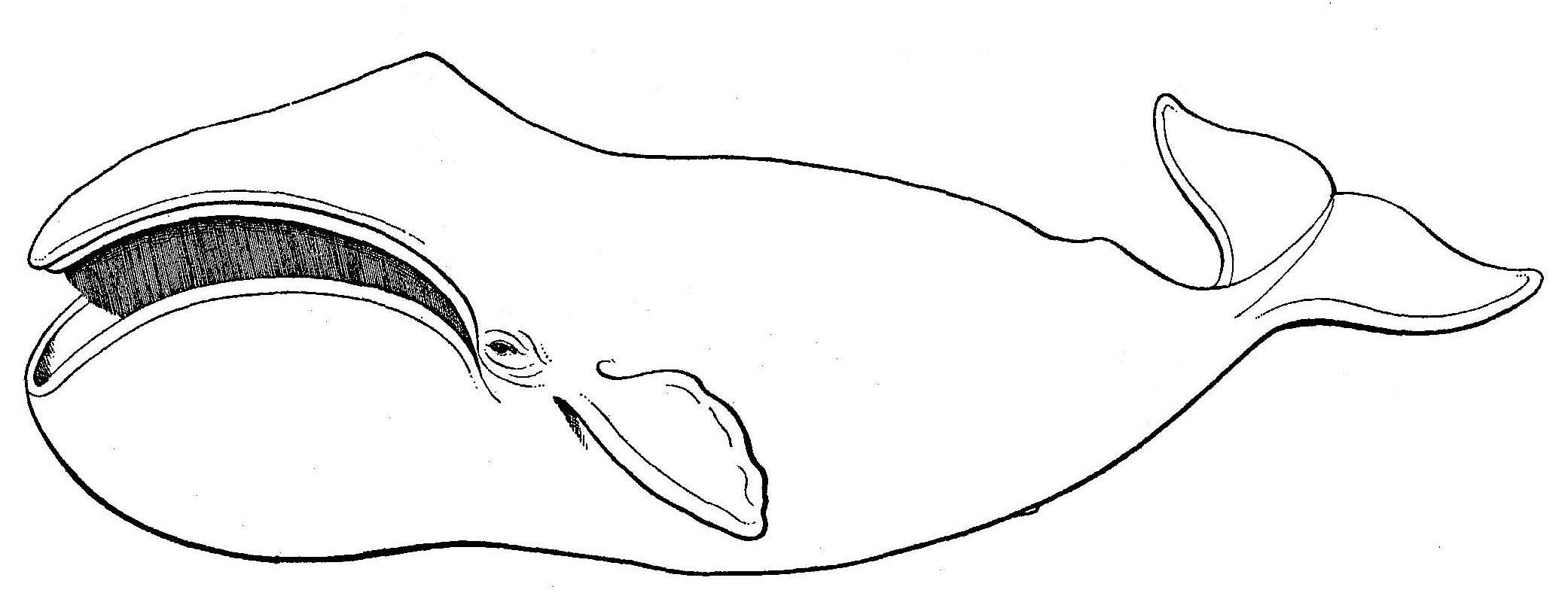

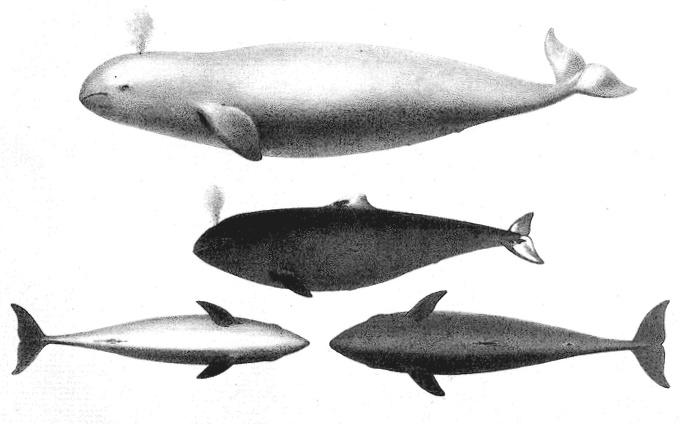

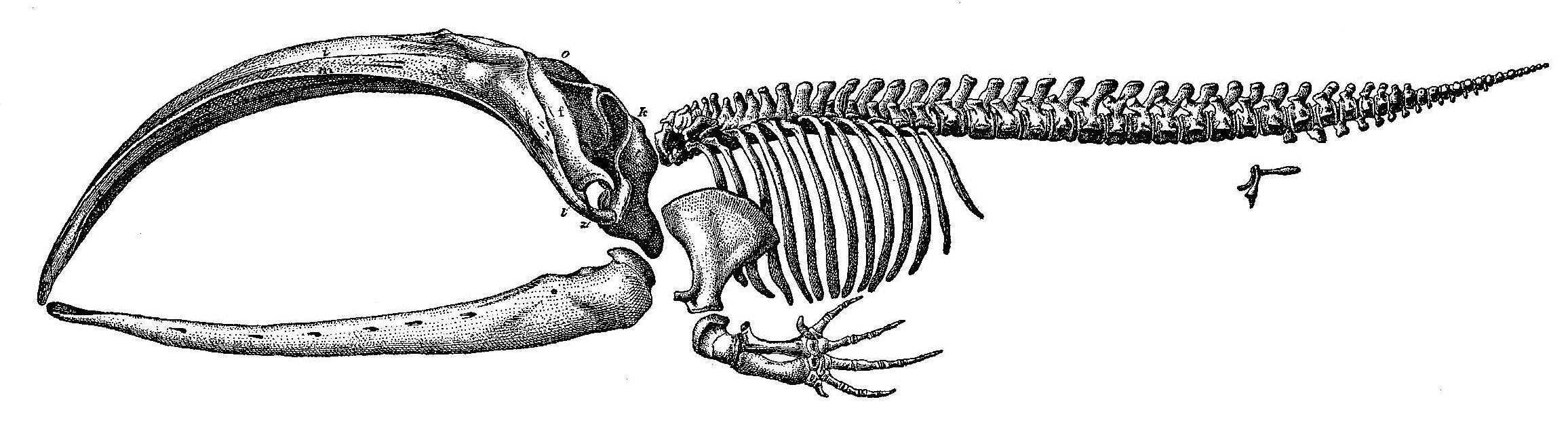

PART I. – CETACEA.INTRODUCTION.The order of Cetacea, as established by naturalists, includes all species of mammalia which have been created for inhabiting the water only; and although their forms bear a strong resemblance to those of the ordinary piscatory tribe, still they are animals having warm blood, breathing by means of lungs, and frequently coming to the surface of the water to respire. In nearly all Cetaceans, the nostrils – termed spiracles or spout-holes – are situated on the top of the head. Through these the thick vaporous breath is ejected into the atmosphere to various altitudes, according to the nature of the animal in this particular respect; and through the same orifices a fresh supply of air is received into its breathing system. Although the Cetaceans are strictly regarded as mammals, they have no true feet; their pectorals being in the form of heavy, bony, and sinewy fins, while the posterior extremity of the body terminates in a broad cartilaginous limb of semi-lunar shape, frequently termed the caudal fin or tail, but known among whalemen as the "flukes," the lobes of which extend horizontally. The different species of Cetaceans are numerous; hence they have been divided into groups, the most prominent of which are the Whalebone Whales, the Cachalots or Sperm Whales, and the Dolphins. The group of Balaenidae, or Whalebone Whales, embraces all those which are destitute of teeth when adult, and whose palate is lined on each side with rows of horny plates, called whalebone or baleen, which are fringed on their inner edges. This part of the animal's organization is peculiarly adapted to the nature of its food, which consists of zoöphytes, mollusks, crustaceans, and small fish. The group of Sperm Whales comprises those with inordinately massive heads, whose upper jaw has only rudimentary teeth, or none at all; whose lower jaw is narrow, rounded toward its anterior extremity, elongated and filling the furrow in the upper one, and furnished on each side with a row of heavy conical teeth, with which to procure and devour the enormous cuttle-fish |

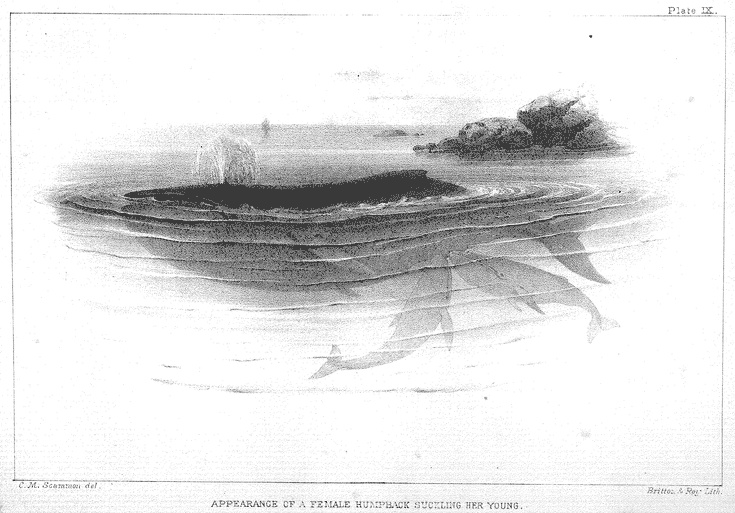

or squid upon which they prey. The group of Dolphins is made up of those comprised in the Linnaean genus Delphinus, and others, whose heads preserve the usual proportion to the body, and whose upper and lower jaws are set with sharp and usually conical teeth. They are the most active and rapacious of the whole order of Cetaceans. All Cetaceans produce their young in nearly the same manner as other mammals. The male is commonly called a bull; the female a cow. The attitude of the two sexes when having intercourse with each other has been differently represented by numerous observers. Some maintain that the male covers the female; while others are positive of their lying on their sides breast to breast, or assuming a perpendicular position. From personal observation, however, we are justified in stating that all are correct. In fact, it may readily be seen that, with their united efforts, it is easy for the animals to sustain any desired position in their native element, during the period of coition. The time of gestation is not known; but from our observations we believe it is never less than nine months, and that in some species it extends to one year. The offspring of the female is called her calf; she nourishes it with rich milk drawn from two teats which lie on each side of her abdomen. All Cetaceans are destitute of the hair or fur which protects the surface of other marine mammals, and instead thereof the dermis is covered by a smooth and transparent scarf-skin. Under the dermis is the thick layer of fat, or "blubber," which infolds the whole creature, whose flesh is dark and sinewy, resembling coarse beef. The natural term of life in Cetaceans can only be approximately determined; it is probably from thirty to a hundred years. The new-born young are clothed in fatless blubber with a thick dermis, and over all is a delicate cuticle. The calf, or "cub," follows the dam for several months – perhaps a year with some species – and during that time draws its chief sustenance from the mother. As her charge matures, its blubber thickens and becomes fat, the dermis becomes thinner but more compact, and the cuticle strengthens and presents a lively glossiness. Among the Balaenidae, the baleen with its fringes grows rapidly, and hardens as it matures. As old age comes on, the fringes to these horny plates become decayed and broken, and in some instances the baleen falls out. The thick blubber, once filled with oil, becomes thin and watery, and, for want of proper sustenance, the animal yields to the course of Nature and dies. Among the Physeteridae, the teeth of the young are sharp and perfect when first developed; but they become more or less broken and worn with age: as years advance, they either fall out or are reduced to a level with the gums, and, like the Balaenidae, being deprived of the |

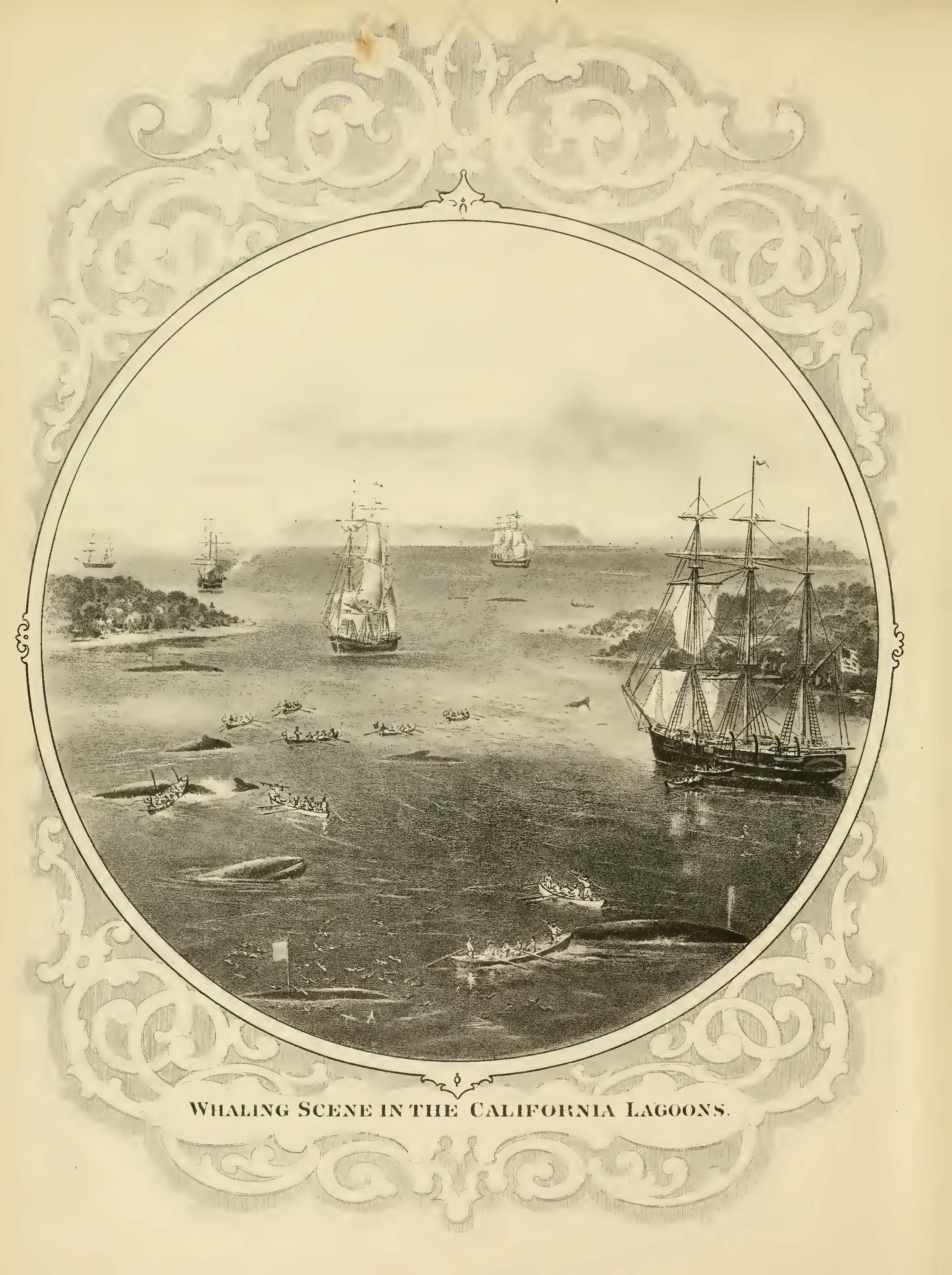

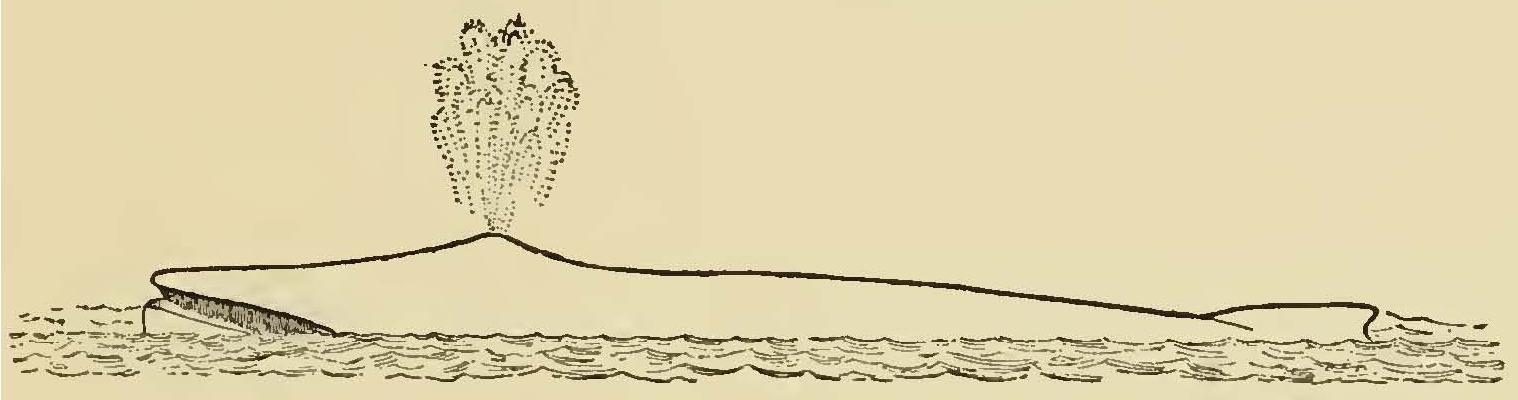

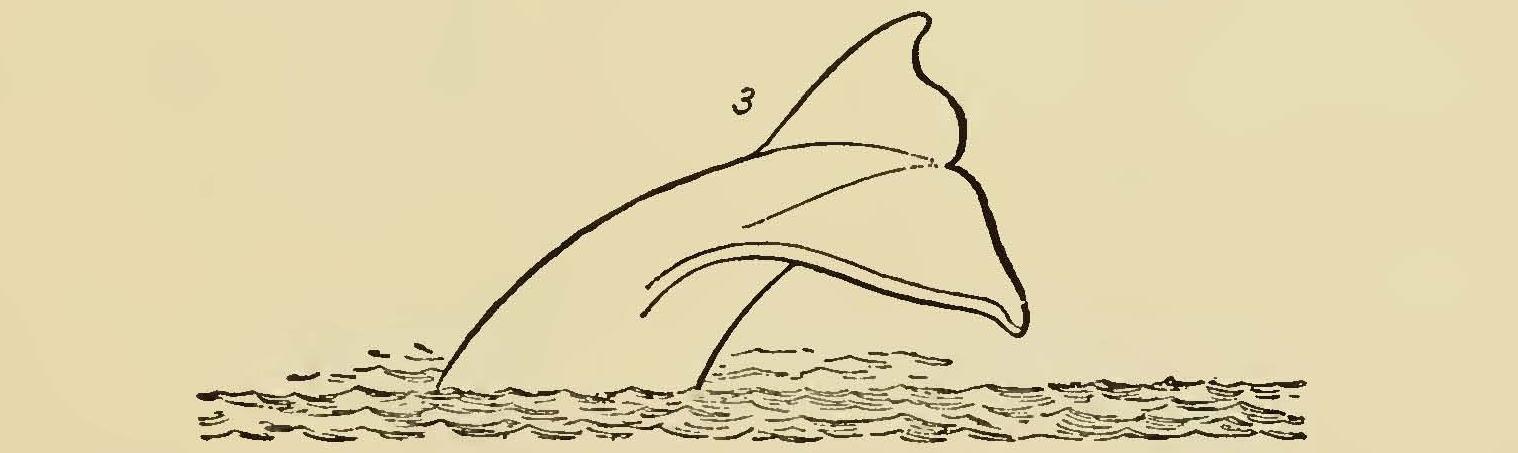

natural means of obtaining food, the animals become emaciated, and at last expire. The same may be said of the Dephinidae or Dolphins. All the Cetaceans propel themselves through the water by the action of their pectorals and caudal fin, and the individual motions of the various species are similar. Usually a small portion of the animal is seen rippling along as it makes its respiration, then, after a few moments, settling below the surface, it again appears in the same manner. When descending to the depths below, it rises a little, as in  figure 1; then pitching headlong, "rounds out," as in figure 2; then "turning  flukes," as in figure 3, disappears. Thus these animals wander through the track-  less waters in their migrations; or, when roving about at leisure on their feeding or breeding grounds, they are sometimes seen in various attitudes, which will be mentioned hereafter. |

CHAPTER I.THE CALIFORNIA GRAY WHALE.

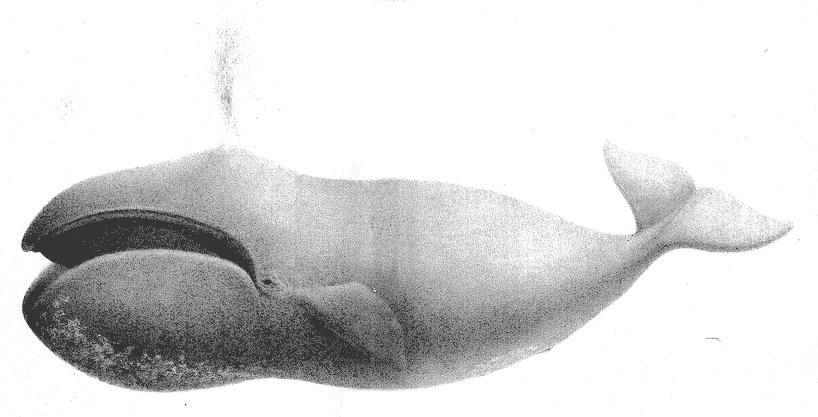

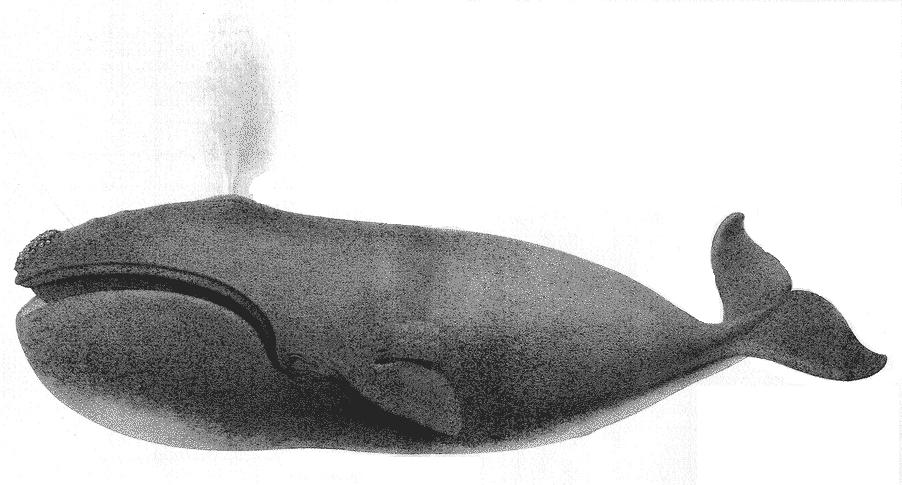

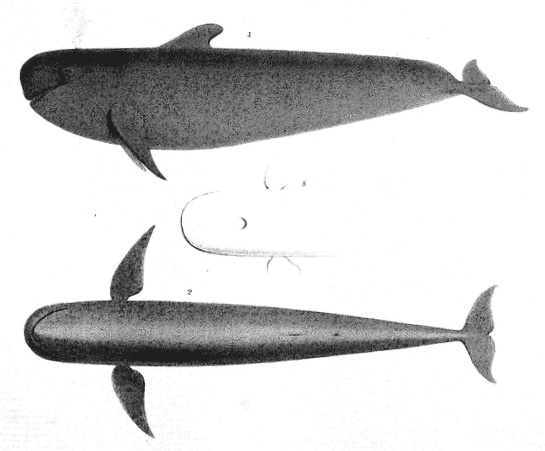

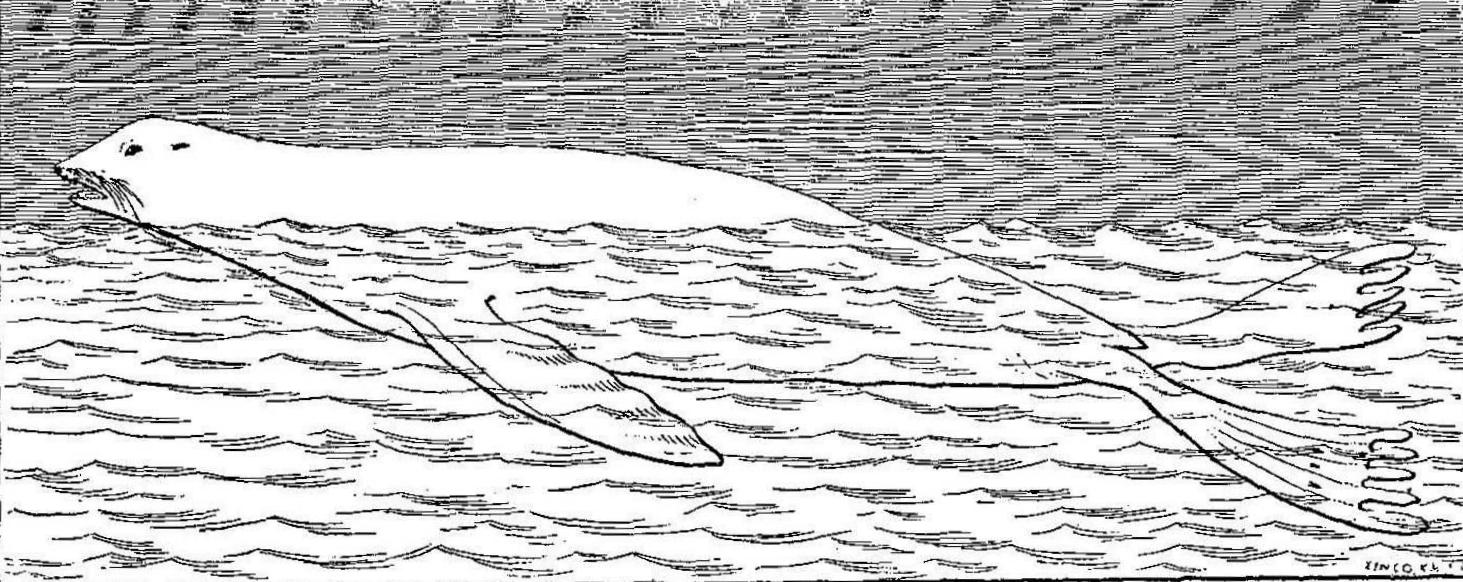

Rhachianectes Glaucus. Cope. (Plate ii, fig. 1.)

The California Gray is unlike other species of baleen whales in color, being of a mottled gray, very light in some individuals, while others, both male and female, are nearly black. The head and jaws are curved downward from near the spiracles to the "nib-end," or extremity of the snout, and the lateral form tapers to a ponderous beak. Under the throat are two longitudinal folds, which are about fifteen inches apart and six feet in length. The eye, the ball of which is at least four inches in diameter, is situated about five inches above and six inches behind the angle of the mouth. The ear, which appears externally like a mere slit in the skin, two and one-half inches in length, is about eighteen inches behind the eye, and a little above it. The length of the female is from forty to forty-four feet,* the fully grown varying but little in size; its greatest circumference, twenty-eight to thirty feet; its flukes, thirty inches in depth, and ten to twelve feet broad. It has no dorsal fin. Its pectorals are about six and one-half feet in length, and three feet in width, tapering from near the middle toward the ends, which are quite pointed. Usually the limbs of the animal vary but little in proportion to its size. The following measurements give the correct proportions of several males taken in the Bay of Monterey, California, since 1865:

* Forty-four feet, however, would be regarded as large, although some individuals have been taken that were much larger, and yielding sixty or seventy barrels of oil. |

|

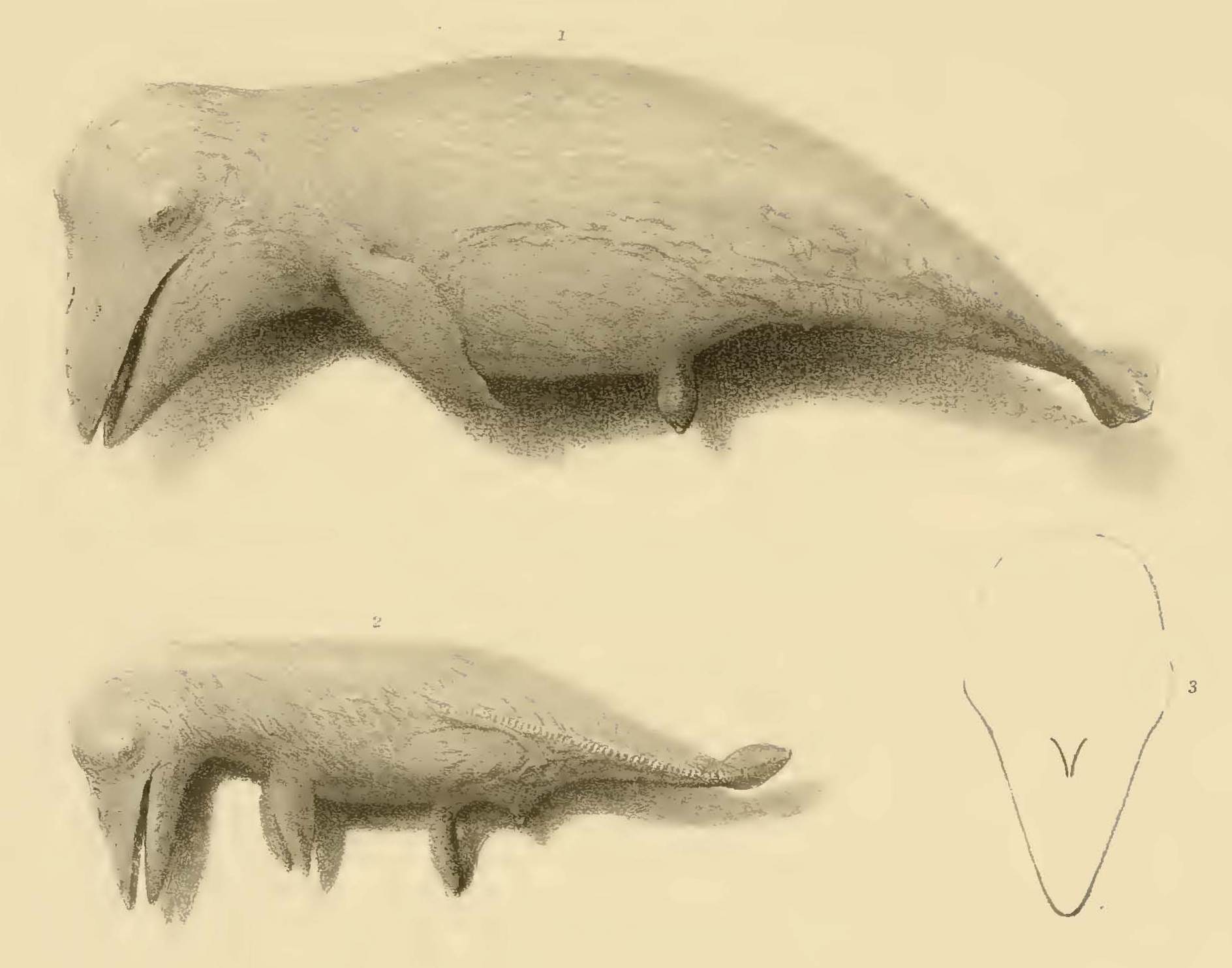

Plate III.

Fig. 1-2 Embryos of a California Gray Whale.

Fig. 3. Outline of Head Showing Spouthole. |

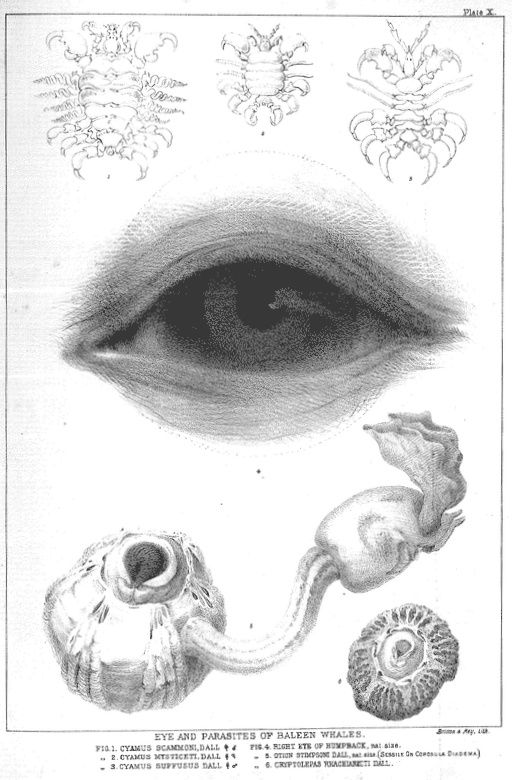

Four other individuals, ranging from thirty-five to forty feet, were measured, the result of which showed corresponding proportions, or nearly so. The animal has a succession of ridges, crosswise along the back, from opposite the vent to the flukes. The coating of fat, or blubber, which possesses great solidity and is exceedingly sinewy and tough, varies from six to ten inches in thickness, and is of a reddish cast. The average yield of oil is twenty barrels. The baleen, of which the longest portion is fourteen to sixteen inches, is of a light brown or nearly white, the grain very coarse, and the hair or fringe on the bone is much heavier and not so even as that of the Right Whale or Humpback. The male may average thirty-five feet in length, but varies more in size than the female, and the usual quantity of oil it produces may be reckoned at twenty-five barrels. Both sexes are infested with parasitical crustaceans (Cyamus Scammoni), and a species of barnacle (Cryptolepas rhachianecti), which collect chiefly upon the head and fins.* * Following is W. H. Dall's description of the Cyamus Scammoni, and of the Cryptolepas rhachianecti (Proceedings Cal. Acad. Sci., Nov. 9th, 1872). Illustrations, figs. 1, 5, plate x.

Genus Cyamus, Lam.

Cyamus, Lam. Syst. An. s. Vert., p. 166. Bate & Westwood, ii, p. 80. Larunda and Panope. Leach. Cyamus Scammoni, n. sp. ♂ Body moderately depressed, of an egg-ovate form; segments slightly separated. Third and fourth segments furnished with a branchia at each side. This, near its base, divides into two cylindrical filaments, spirally coiled from right to left. At the base of each branchia are two slender accessory filaments, not coiled, quite short, and situated, one before and the other behind the base of the main branchia. Second pair of hands, kidney-shaped, with the carpal articulation halfway between the distal and proximal ends, and having two pointed tubercles on the inferior edge, before the carpal joint. Third and fourth segments somewhat punctate above; all the oth- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The California Gray Whale is only found in north latitudes, and its migrations have never been known to extend lower than 20° north. It frequents the coast of California from November to May. During these months the cows enter the lagoons on the lower coast to bring forth their young,* while the males remain outside ers smooth; the sixth and seventh slightly serrate on the upper anterior edge, and without ventral spines. Color, yellowish white. Lon. 0.70, lat. 0.39 in., of largest specimen. ♀ Similar to the ♂ in all respects, excepting in being a little more slender, and in wanting the accessory appendages to the branchiae; the ovigerous sacs are four in number, overlapping each other. Habitat, on the California Gray Whale (Rhachianectes glaucus of Cope), upon the Coast of California; very numerous. I may remark here that these species are all so distinct from those figured by Milne-Edwards, Gosse, and Bate & Westwood, that a comparative description has seemed unnecessary; also, that the species obtained on different species of Cetaceans have so far been found invariably distinct. The inference is, of course, that each Cetacean has its peculiar parasites – a supposition which agrees with our knowledge of the facts in many groups of terrestrial animals. Cryptolepas rhachianecti, Dall, n. s. Valves subequal, rostrum radiate, not alate. Lateral valves anteriorly alate, posteriorly radiate; carina alate, not radiate. Each valve internally transversely deeply grooved, and furnished externally with six radiating laminae, vertically sharply grooved; the adjacent terminal laminae of each two valves coalescing to form one lamina of extra thickness; all the laminae bifurcated and thickened toward the outer edges, with two or more short spurs on each side, irregularly placed between the shell-wall and the bifurcation. Superior terminations of the valves (bluntly pointed?) usually abraded, transversely striate. Scuta subquadrate, adjacent anteriorly, and very slightly beaked in the middle of the occludent margin; terga subquadrate, small, separated from the scuta by intervening membrane; both very small in proportion to the orifice. Membranes very thin and delicate, raised into small lamellae between the opercular valves. All the calcareous matter pulverulent, and showing a strong tendency to split up into laminae. Antero-posterior diameter of large specimen, 1.62 inch; ditto of orifice, 0.63 inch; transverse diameter of orifice, 0.58 inch; lon. scuta, 0.17 inch; lat. ditto, 0.08 inch; lon. terga, 0.07 inch; lat. ditto, 0.07 inch. Color of membranes, when living, sulphur yellow; hood, extremely protrusile. This species is found sessile on the California Gray Whale (Rhachianectes glaucus, Cope). I have observed them on specimens of that species hauled up on the beach at Monterey for cutting off the blubber, in the bay-whaling of that locality. The superior surface of the lateral laminae, being covered by the black skin of the whale, is not visible; and the animal, removed from its native element – protruding its bright yellow hood in every direction, to a surprising distance, as if gasping for breath – presented a truly singular appearance. * The question is often raised, as to whether the cetaceous animals have more than one young one at a birth? but it seems evident to us that they never have more than two, for Nature has made no provision whereby more than that number could draw sustenance at the same time from the parent animal; and even where provision is made for two among the marine mammalia, particularly in the case of the seal tribe, it is rarely if ever that the female produces twins. It is true that instances have occurred where two, three, or more cubs have been seen with one California Gray Whale; but this has only happened in the lagoons where there had been great slaughter among the cows, leaving their young ones motherless, so that these straggle about, sometimes following other whales, sometimes clustering by themselves a half-dozen together. We know of one instance where a whale which had a calf perhaps a month old was killed close to a ship. When the mother was taken to the ship to be cut in, the young one followed, and remained playing about for two weeks; but |

along the sea-shore. The time of gestation is about one year.* Occasionally a male is seen in the lagoons with the cows at the last of the season, and soon after both male and female, with their young, will be seen working their way northward, following the shore so near that they often pass through the kelp near the beach. It is seldom they are seen far out at sea. This habit of resorting to shoal bays is one in which they differ strikingly from other whales. In summer they congregate in the Arctic Ocean and Okhotsk Sea. It has been said that this species of whale has been found on the coast of China and about the shores of the island of Formosa, but the report needs confirmation. In October and November the California Grays appear off the coast of Oregon and Upper California, on their way back to their tropical haunts, making a quick, low spout at long intervals; showing themselves but very little until they reach the smooth lagoons of the lower coast, where, if not disturbed, they gather in large numbers,† passing and repassing into and out of the estuaries, or slowly raising their colossal forms midway above the surface, falling over on their sides as if by whether it lived to come to maturity is a matter of conjecture. * This statement is maintained upon the following observations: We have known of five embryos being taken from females between the latitudes of 31° and 37° north, on the California coast, when the animals were returning from their warm winter haunts to their cool summer resorts, and in every instance they were exceedingly fat, which is quite opposite to the cows which have produced and nurtured a calf while in the lagoons; hence we conclude that the animals propagate only once in two years. † It has been estimated, approximately, by observing men among the shore-whaling parties, that a thousand whales passed southward daily, from the 15th of December to the 1st of February, for several successive seasons after shore-whaling was established, which occurred in 1851. Captain Packard, who has been engaged in the business for over twenty years, thinks this a low estimate. Accepting this number without allowing for those which passed off shore out of sight from the land, or for those which passed before the 15th of December and after the 1st of February, the aggregate would be increased to 47,000. Captain Packard also states, that at the present time the average number seen from the stations passing daily would not exceed forty. From our own observation upon the coast, we are inclined to believe that the numbers resorting annually to the coast of California, from 1853 to 1856, did not exceed 40,000 – probably not over 30,000; and at the present time there are many which pass off shore at so great a distance as to be invisible from the lookout stations: there are probably between 100 and 200 whales going southward daily, from the beginning to the end of the "down season" (from December 15th to February 1st). This estimate of the annual herd visiting the coast is probably not large, as there is no allowance made for those that migrate earlier and later in the season. From what data we have been able to obtain, the whole number of California Gray Whales which have been captured or destroyed since the bay-whaling commenced, in 1846, would not exceed 10,800, and the number which now periodically visit the coast does not exceed 8,000 or 10,000. |

accident, and dashing the water into foam and spray about them. At times, in calm weather, they are seen lying on the water quite motionless, keeping one position for an hour or more. At such times the sea-gulls and cormorants frequently alight upon the huge beasts. The first season in Scammon's Lagoon, coast of Lower California, the boats were lowered several times for them, we thinking that the animals when in that position were dead or sleeping, but before the boats arrived within even shooting distance they were on the move again. About the shoals at the mouth of one of the lagoons, in 1860, we saw large numbers of the monsters. It was at the low stage of the tide, and the shoal places were plainly marked by the constantly foaming breakers. To our surprise we saw many of the whales going through the surf where the depth of water was barely sufficient to float them. We could discern in many places, by the white sand that came to the surface, that they must be near or touching the bottom. One in particular, lay for a half-hour in the breakers, playing, as seals often do in a heavy surf; turning from side to side with half-extended fins, and moved apparently by the heavy ground-swell which was breaking; at times making a playful spring with its bending flukes, throwing its body clear of the water, coming down with a heavy splash, then making two or three spouts, and again settling under water; perhaps the next moment its head would appear, and with the heavy swell the animal would roll over in a listless manner, to all appearance enjoying the sport intensely. We passed close to this sportive animal, and had only thirteen feet of water. The habits of the Gray have brought upon it many significant names, among which the most prominent are, "Hard-head," "Mussel-digger," "Devil-fish," "Gray-back," and "Rip-sack." The first-mentioned misnomer arose from the fact of the animals having a great propensity to root the boats when coming in contact with them, in the same manner that hogs upset their empty troughs. Moreover, they are known to descend to soft bottoms in search of food, or for other purposes; and, when returning to the surface, they have been seen with head and lips besmeared with the dark ooze from the depths below;* hence the name of * To our personal knowledge, but little or no food has been found in the animal's stomach. We have examined several taken in the lagoons, and in them we found what the whalers called "sedge" or "sea-moss" (a sort of sea-cabbage), which at certain seasons darkens the waters in extensive patches both in and about the mouths of the estuaries. Whether this was taken into the stomach as food some naturalists doubt, giving as a reason that the whale, passing through the water mixed with this vegetable matter, on opening its mouth would of necessity receive more or less of it, which would be swallowed, there being no other way in which it could be |

|

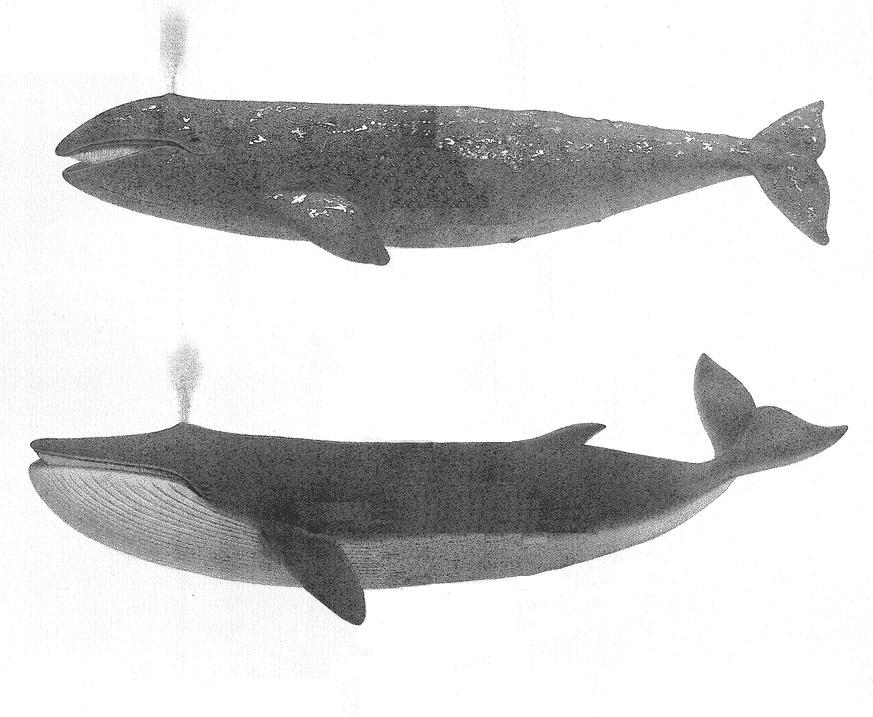

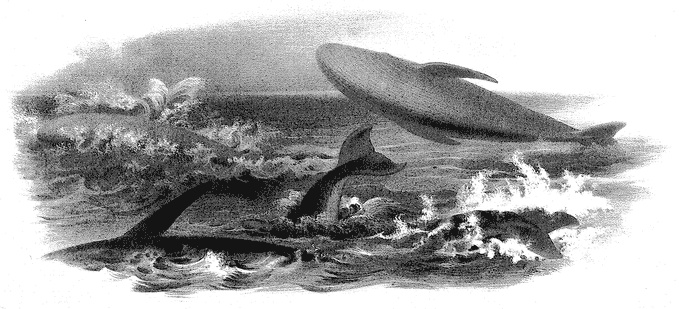

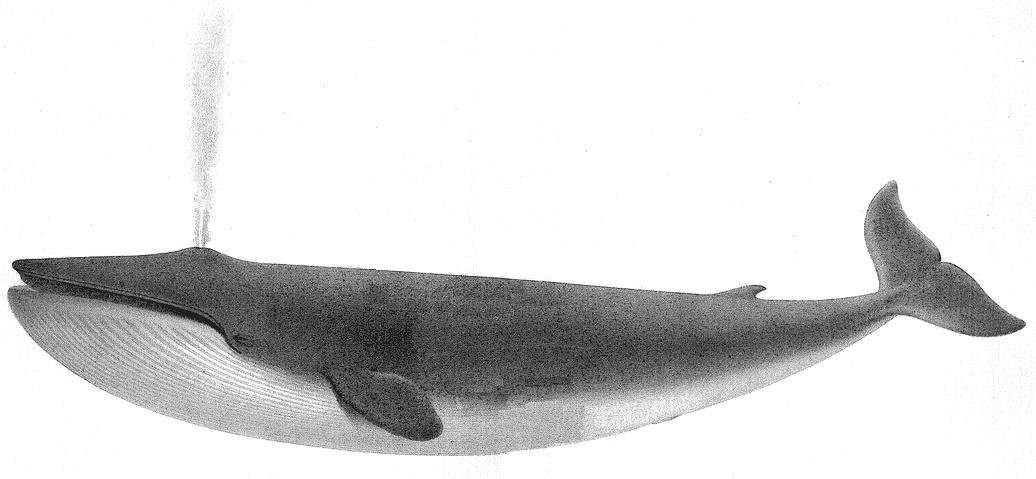

Plate II.

Fig. 1. The California Gray Whale (Rhachianectes Glaucus, Cope.)

Fig. 2. The Finback (Balaenoptera Velifera, Cope.) |

"Mussel-digger." "Devil-fish" is significant of the danger incurred in the pursuit of the animal. "Gray-back" is indicative of its color, and "Rip-sack" originated with the manner of flensing. As the season approaches for the whales to bring forth their young, which is from December to March, they formerly collected at the most remote extremities of the lagoons, and huddled together so thickly that it was difficult for a boat to cross the waters without coming in contact with them. Repeated instances have been known of their getting aground and lying for several hours in but two or three feet of water, without apparent injury from resting heavily on the sandy bottom, until the rising tide floated them. In the Bay of Monterey they have been seen rolling, with apparent delight, in the breakers along the beach. In February, 1856, we found two whales aground in Magdalena Bay. Each had a calf playing about, there being sufficient depth for the young ones, while the mothers were lying hard on the bottom. When attacked, the smaller of the two old whales lay motionless, and the boat approached near enough to "set" the hand-lance into her "life," dispatching the animal at a single dart. The other, when approached, would raise her head and flukes above the water, supporting herself on a small portion of the belly, turning easily, and heading toward the boat, which made it very difficult to capture her. It appears to be their habit to get into the shallowest inland waters when their cubs are young. For this reason the whaling-ships anchor at a considerable distance from where the crews go to hunt the animals, and several vessels are often in the same lagoon. The first streak of dawn is the signal for lowering the boats, all pulling for the head-waters, where the whales are expected to be found. As soon as one is seen, the officer who first discovers it sets a "waif" (a small flag) in his boat, and gives chase. Boats belonging to other vessels do not interfere, but go in search of other whales. When pursuing, great care is taken to keep behind, and a short distance from the animal, until it is driven to the extremity of the lagoon, or into shoal water; then the men in the nearest boats spring to their oars in the exciting race, and the animal, swimming so near the bottom, has its progress impeded, thereby giving its pursuers a decided advantage: although occasionally it will suddenly change its course, or "dodge," which frequently prolongs the chase for hours, disposed of. The quantity found in any one individual would not exceed a barrelful. From the testimony of several whaling-men whom we regard as interested and careful observers, together with our own investigations, we are convinced that mussels have been found in the maws of the California Grays; but as yet, from our own observations, we have not been able to establish the fact of what their principal sustenance consists. |

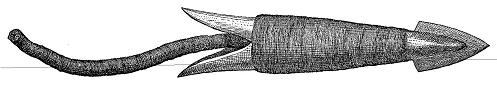

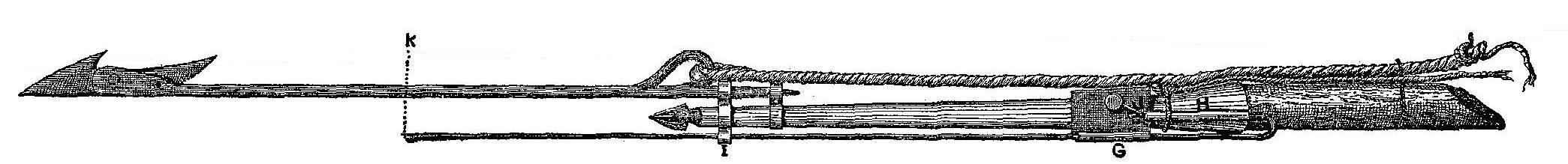

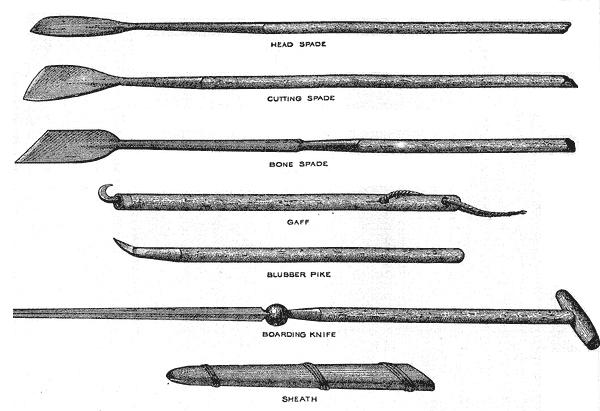

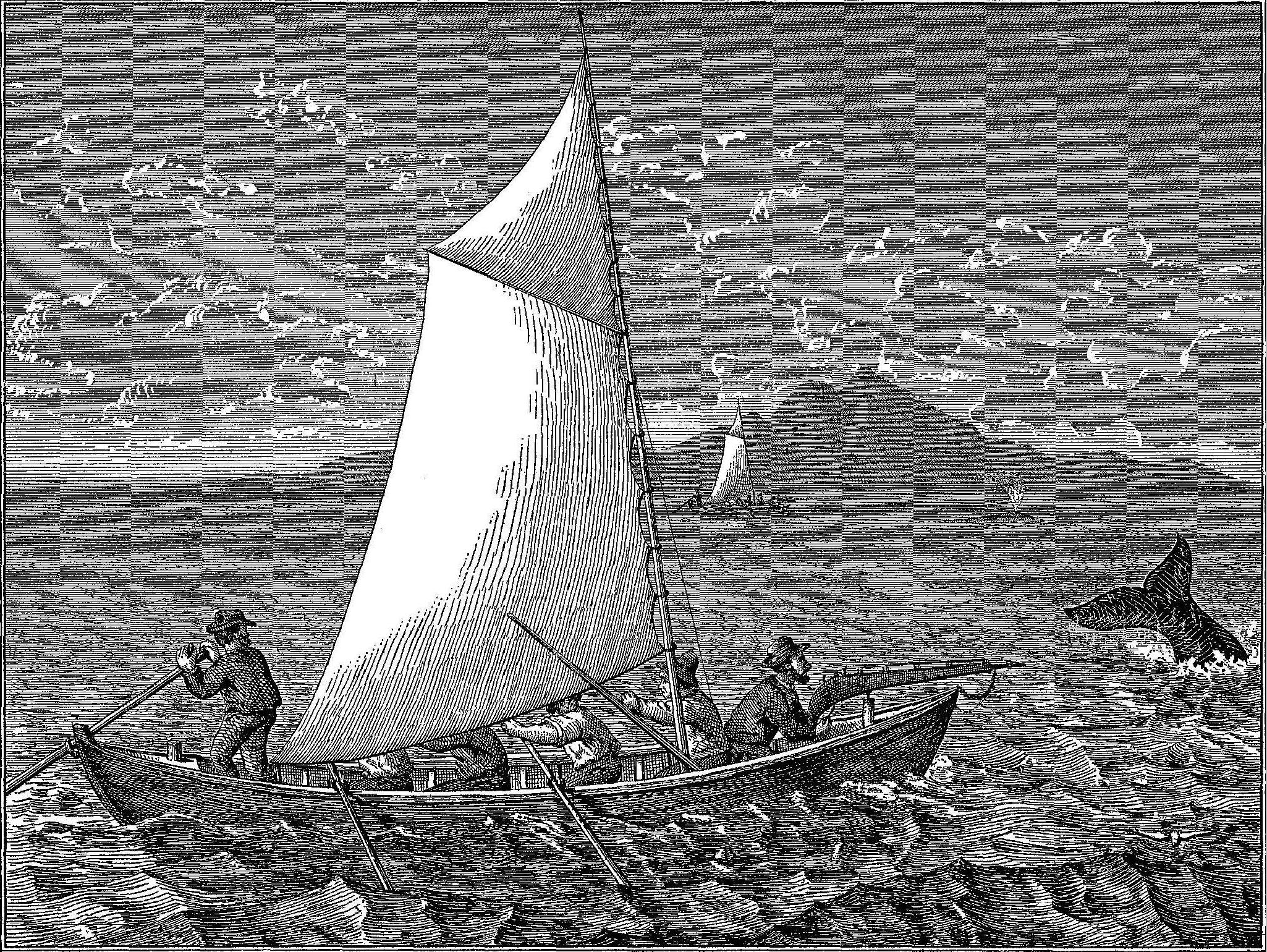

the boats cutting through the water at their utmost speed. At other times, when the cub is young and weak, the movements of the mother are sympathetically suited to the necessities of her dependent offspring. It is rare that the dam will forsake her young one, when molested. When within "darting distance" (sixteen or eighteen feet), the boat-steerer darts the harpoons, and if the whale is struck it dashes about, lashing the water into foam, oftentimes staving the boats. As soon as the boat is fast, the officer goes into the head,* and watches a favorable opportunity to shoot a bomb-lance. Should this enter a vital part and explode, it kills instantly, but it is not often this good luck occurs; more frequently two or three bombs are shot, which paralyze the animal to some extent, when the boat is hauled near enough to use the hand-lance. After repeated thrusts, the whale becomes sluggish in its motions; then, going "close to," the hand-lance is set into its "life," which completes the capture. The animal rolls over on its side, with fins extended, and dies without a struggle. Sometimes it will circle around within a small compass, or take a zigzag course, heaving its head and flukes above the water, and will either roll over, "fin out," or die under water and sink to the bottom. Thus far we have spoken principally of the females, as they are found in the lagoons. Mention has been made, however, of that general habit, common to both male and female, of keeping near the shore in making the passage between their northern and southern feeding-grounds. This fact becoming known, and the bomb gun† coming into use, the mode of capture along the outer coast was changed. The whaling parties first stationed themselves in their boats at the most favorable points, where the thickest beds of kelp were found, and there lay in wait watching for a good chance to shoot the whales as they passed. This was called "kelp whaling." The first year or two that this pursuit was practiced, many of the animals * Whalemen call the forward part of a whale-boat the head, differing from merchantmen, who term it the bow; still, the oar next to the forward one in a whale-boat is named the bow-oar. And, likewise, when the boat is hauled close up to the whale by heaving the line out of the "bow-chocks," and taking it to one side against a cleat which is placed a few feet aft of the extreme bow, it is called "bowing-on." † The bomb-gun is made of iron, stock and all. It is three feet long, the barrel of which is twenty-three inches in length; diameter of bore, one and one-eighth of an inch; weight, twenty-four pounds. It shoots a bomb-lance twenty-one and a half inches long, and of a size to fit the bore. It is pointed at the end, with sharpened edges, in order to cut its way through the fibrous fat and flesh, and is guided by three elastic feathers, which are attached along the fuse tube, folding around it when in the barrel. The gun is fired from the shoulder, in the same way as a musket. For illustration, see plate xxiii. |

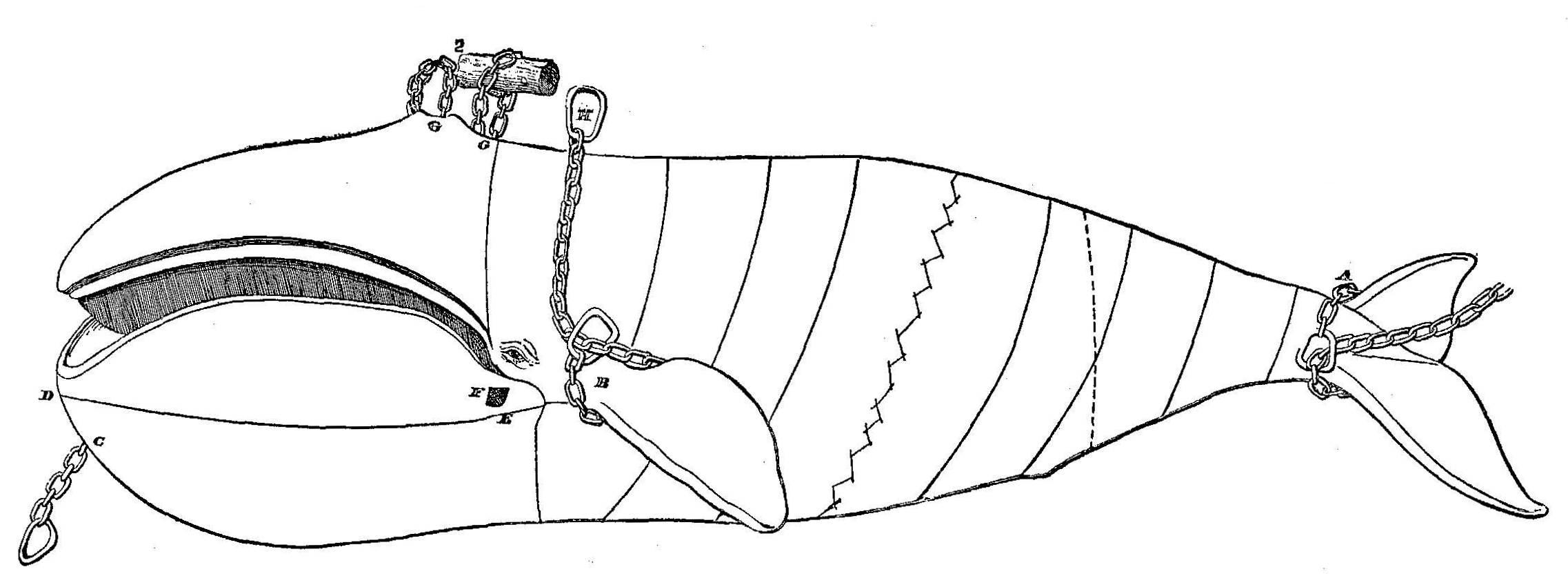

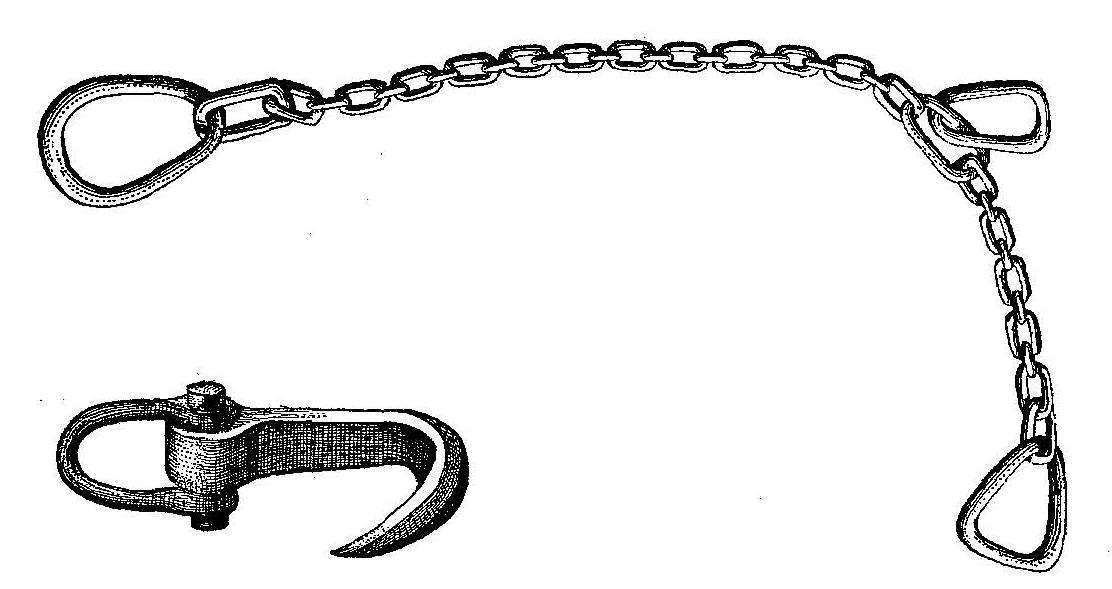

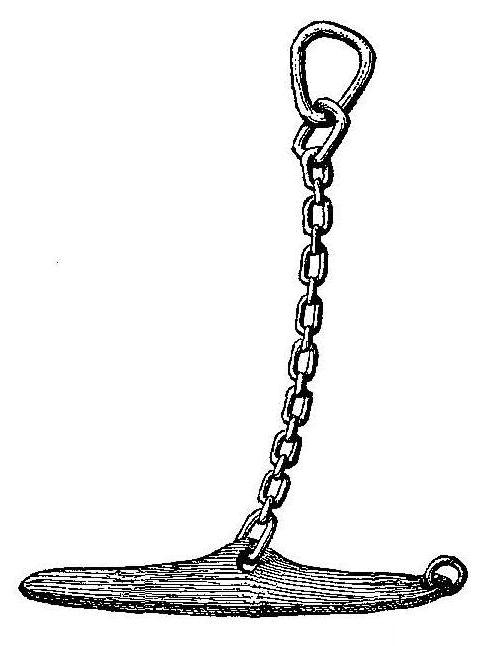

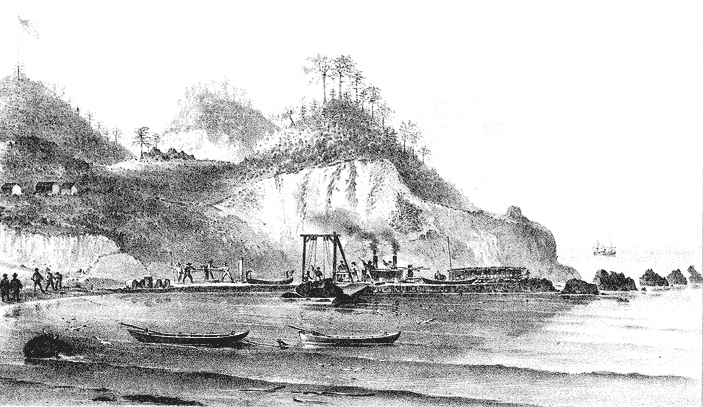

passed through or along the edge of the kelp, where the gunners chose their own distance for a shot. This method, however, soon excited the suspicious of these sagacious creatures. At first, the ordinary whale-boat was used, but the keen-eyed "Devil-fish" soon found what would be the consequence of getting too near the long, dark-looking object, as it lay nearly motionless, only rising and falling with the rolling swell. A very small boat – with one man to scull and another to shoot – was then used, instead of the whale-boat. This proved successful for a time, but, after a few successive seasons, the animals passed farther seaward, and at the present time the boats usually anchor outside the kelp. The mottled fish being seen approaching far enough off for the experienced gunner to judge nearly where the animal will "break water," the boat is sculled to that place, to await the "rising." If the whale "shows a good chance," it is frequently killed instantly, and sinks to the bottom, or receives its death-wound by the bursting of the bomb-lance. Consequently, the stationary position or slow movement of the animal enables the whaler to get a harpoon into it before sinking. To the harpoon a line is attached, with a buoy, which indicates the place where the dead creature lies, should it go to the bottom. Then, in the course of twenty-four hours, or in less time, it rises to the surface, and is towed to the shore, the blubber taken off and tried out in pots set for that purpose upon the beach. Another mode of capture is by ships cruising off the land and sending their boats inshore toward the line of kelp; and, as the whales work to the southward, the boats, being provided with extra large sails, the whalemen take advantage of the strong northerly winds, and, running before the breeze, sail near enough to be able to dart the hand-harpoon into the fish. "Getting fast" in this way, it is killed in deep water, and, if inclined to sink, it can be held up by the boats till the ship comes up, when a large "fluke-rope" is made fast, or the "fin-chain" is secured to one fin, the "cutting-tackle" hooked, and the whale "cut in" immediately. This mode is called "sailing them down." Still another way of catching them is with "Greener's Harpoon Gun," which is similar to a small swivel-gun. It is of one and a half inch bore, three feet long in the barrel, and, when stocked, weighs seventy-five pounds. The harpoon, four feet and a half long, is projected with considerable accuracy to any distance under eighty-four yards. The gun is mounted on the bow of the boat. A variety of manoeuvres are practiced when using the weapon: at times the boat lying at anchor, and, again, drifting about for a chance-shot. When the animal is judged to be ten fathoms off, the gun is pointed eighteen inches below the back; if fifteen fathoms, eight or ten inches below; if eighteen or twenty fathoms distant, the gun is sighted at the top of its back. |

Still another strategic plan has been practiced with successful results, called "whaling along the breakers." Mention has been already made of the habit which these whales have of playing about the breakers at the mouths of the lagoons. This, the watchful eye of the whaler was quick to see, could be turned to his advantage. After years of pursuit by waylaying them around the beds of kelp, the wary animals learned to shun these fatal regions, making a wide deviation in their course to enjoy their sports among the rollers at the lagoons' mouths, as they passed them either way. But the civilized whaler anchors his boats as near the roaring surf as safety will permit, and the unwary "Mussel-digger" that comes in reach of the deadly harpoon, or bomb-lance, is sure to pay the penalty with its life. If it come within darting distance, it is harpooned; and, as the stricken animal makes for the open sea, it is soon in deep water, where the pursuer makes his capture with comparative ease; or if passing within range of the bomb-gun, one of the explosive missiles is planted in its side, which so paralyzes the whale that the fresh boat's-crew, who have been resting at anchor, taking to their oars, soon overtake and dispatch it. The casualties from coast and kelp whaling are nothing to be compared with the accidents that have been experienced by those engaged in taking the females in the lagoons. Hardly a day passes but there is upsetting or staving of boats, the crews receiving bruises, cuts, and, in many instances, having limbs broken; and repeated accidents have happened in which men have been instantly killed, or received mortal injury. The reasons of the increased dangers are these: the quick and deviating movements of the animal, its unusual sagacity, and the fact of the sandy bottom being continually stirred by the strong currents, making it difficult to see an object at any considerable depth. When a whale is "struck" at sea, there is generally but little difficulty in keeping clear. When first irritated by the harpoon, it attempts to escape by "running," or descending to the depths below, taking out more or less line, the direction of which, and the movements of the boat, indicate the animal's whereabouts. But in a lagoon, the object of pursuit is in narrow passages, where frequently there is a swift tide, and the turbid water prevents the whaler from seeing far beneath the boat. Should the chase be made with the current, the fugitive sometimes stops suddenly, and the speed of the boat, together with the influence of the running water, shoots it upon the worried animal when it is dashing its flukes in every direction. The whales that are chased have with them their young cubs, and the mother, in her efforts to avoid the pursuit of herself and offspring, may momentarily lose sight of her little one. Instantly she |

|

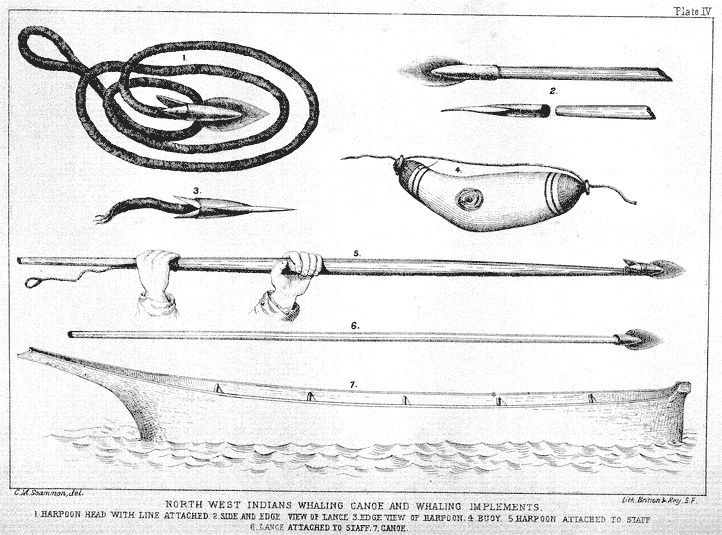

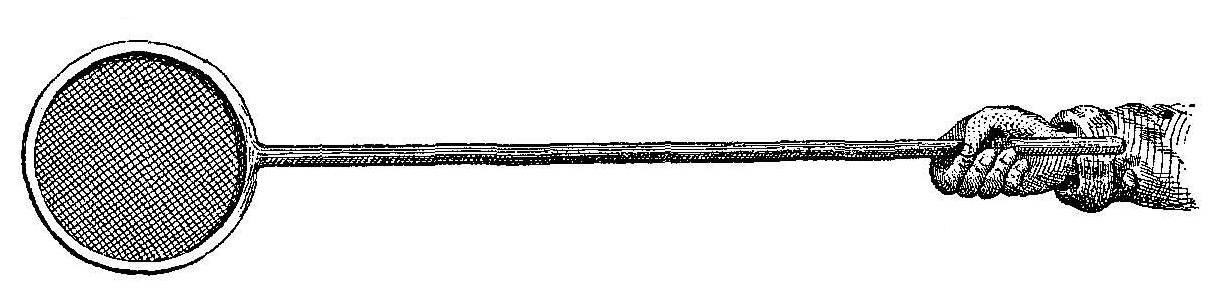

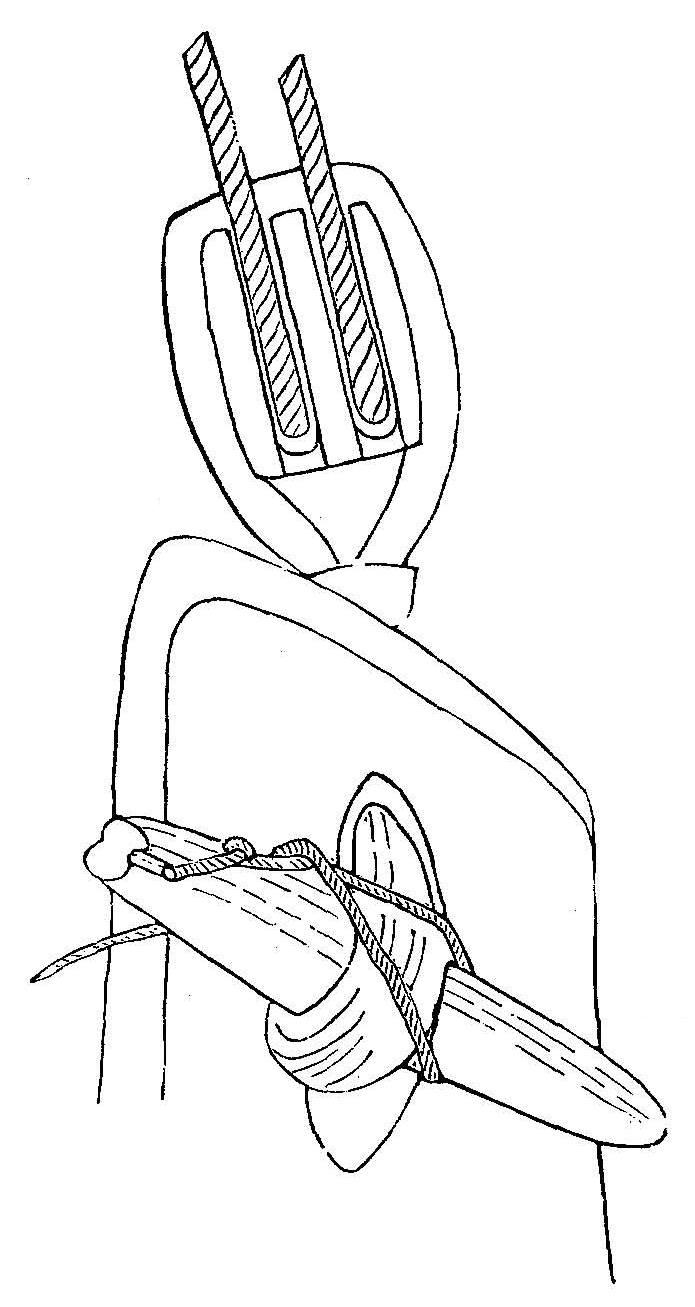

Plate IV.

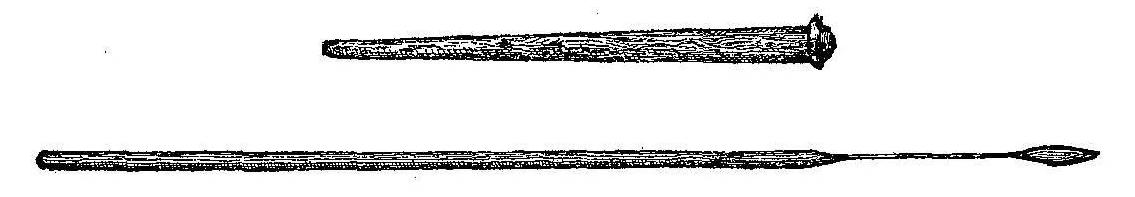

North West Indians Whaling Canoe and Whaling Implements.

1. Harpoon Head with Line Attached. 2. Side and Edge View of Lance.

3. Edge View of Harpoon. 4. Buoy. 5. Harpoon Attached to Staff. 6. Lance Attached to Staff. 7. Canoe. |

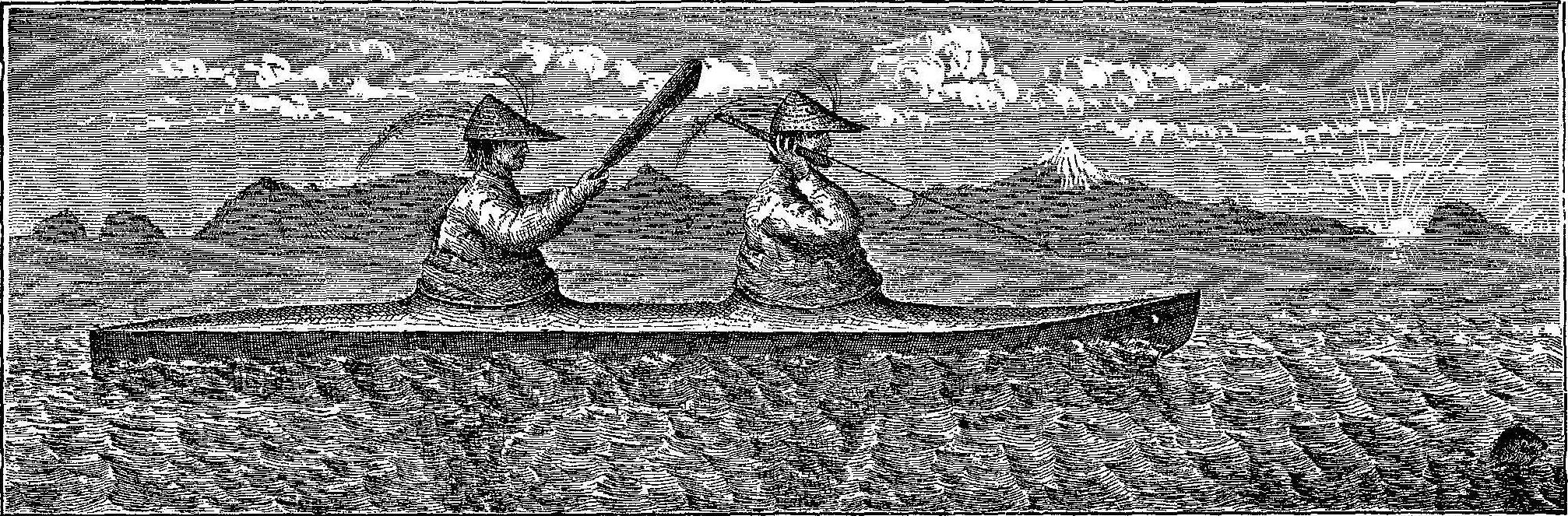

will stop and "sweep" around in search, and if the boat comes in contact with her, it is quite sure to be staved. Another danger is, that in darting the lance at the mother, the young one, in its gambols, will get in the way of the weapon, and receive the wound, instead of the intended victim. In such instances, the parent animal, in her frenzy, will chase the boats, and, overtaking them, will overturn them with her head, or dash them in pieces with a stroke of her ponderous flukes. Sometimes the calf is fastened to instead of the cow. In such instances the mother may have been an old frequenter of the ground, and been before chased, and perhaps have suffered from a previous attack, so that she is far more difficult to capture, staving the boats and escaping after receiving repeated wounds. One instance occurred in Magdalena Lagoon, in 1857, where, after several boats had been staved, they being near the beach, the men in those remaining afloat managed to pick up their swimming comrades, and, in the meantime, to run the line to the shore, hauling the calf into as shallow water as would float the dam, she keeping near her troubled young one, giving the gunner a good chance for a shot with his bomb-gun from the beach. A similar instance occurred in Scammon's Lagoon, in 1859. The testimony of many whaling-masters furnishes abundant proof that these whales are possessed of unusual sagacity. Numerous contests with them have proved that, after the loss of their cherished offspring, the enraged animals have given chase to the boats, which only found security by escaping to shoal water or to shore. After evading the civilized whaler and his instruments of destruction, and perhaps while they are suffering from wounds received in their southern haunts, these migratory animals begin their northern journey. The mother, with her young grown to half the size of maturity, but wanting in strength, makes the best of her way along the shores, avoiding the rough sea by passing between or near the rocks and islets that stud the points and capes. But scarcely have the poor creatures quitted their southern homes before they are surprised by the Indians about the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Vancouver and Queen Charlotte's Islands. Like enemies in ambush, these glide in canoes from island, bluff, or bay, rushing upon their prey with whoop and yell, launching their instruments of torture, and like hounds worrying the last life blood from their vitals. The capture having been effected, trains of canoes tow the prize to shore in triumph. The whalemen among the Indians of the North-west Coast are those who delight in the height of adventure, and who are ambitious of acquiring the greatest reputation among their fellows. Those among them who could boast of killing a whale, formerly had the most exalted mark of |

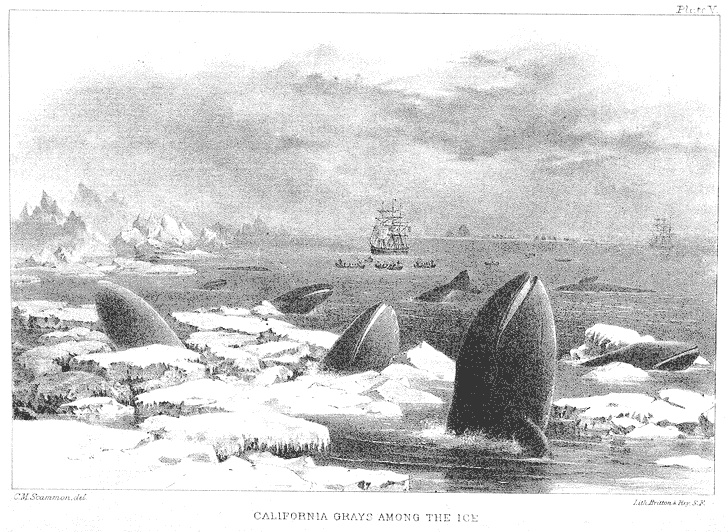

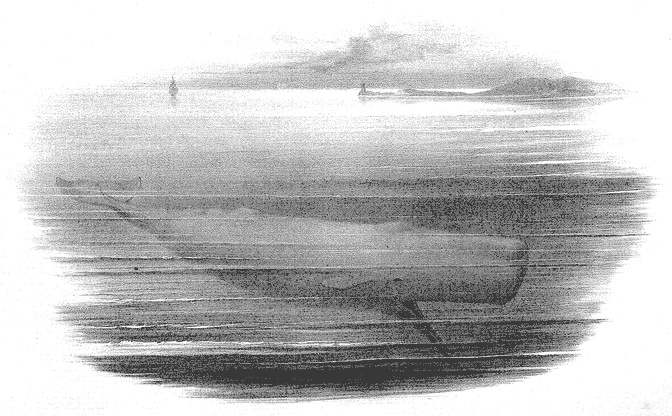

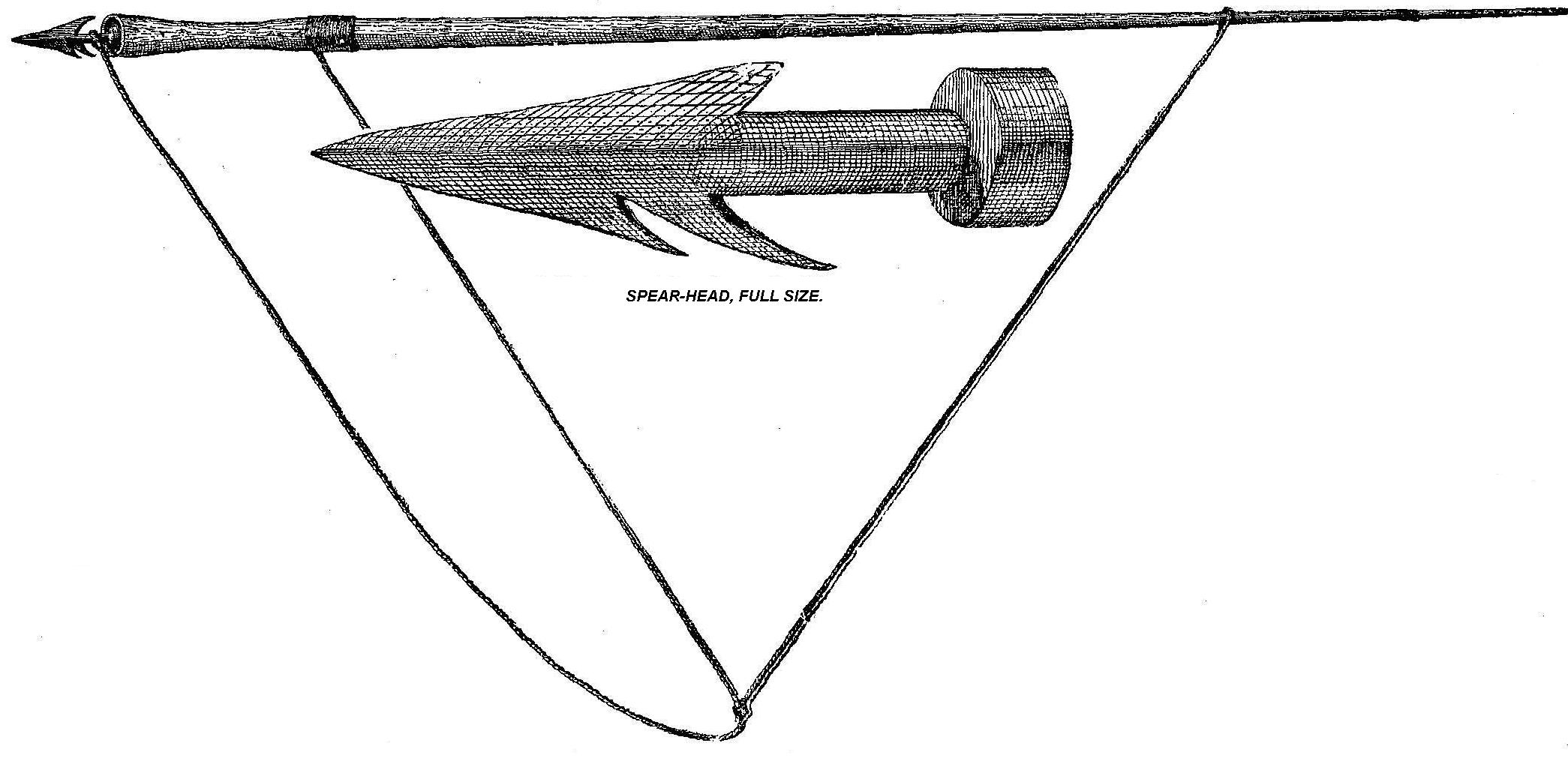

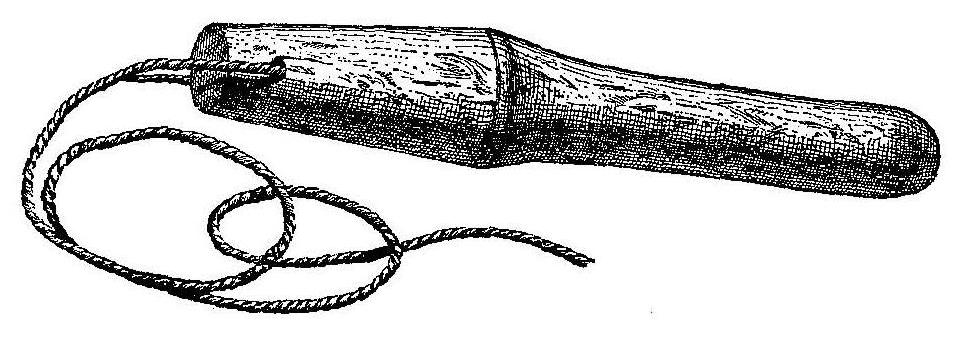

honor conferred upon them by a cut across the nose; but this custom is no longer observed. The Indian whaling-canoe is thirty-five feet in length. Eight men make the crew, each wielding a paddle five and a half feet long. The whaling-gear consists of harpoons, lines, lances, and seal-skin buoys, all of their own workmanship. The cutting material of both lance and spear was formerly the thick part of a mussel-shell, or of the "abelone;" the line made from cedar withes, twisted into a three-strand rope. The buoys are fancifully painted, but those belonging to each boat have a distinguishing mark. The lance-pole, or harpoon-staff, made of the heavy wood of the yew-tree, is eighteen feet long, weighing as many pounds, and with the lance attached is truly a formidable weapon. Their whaling-grounds are limited, as the Indians rarely venture seaward far out of sight of the smoke from their cabins by day, or beyond view of their bonfires at night. The number of canoes engaged in one of these expeditions is from two to five, the crews being taken from among the chosen men of the tribe, who, with silent stroke, can paddle the symmetrical canim close to the rippling water beside the animal; the bowman then, with sure aim, thrusts the harpoon into it, and heaves the line and buoys clear of the canoe. The worried creature may dive deeply, but very little time elapses before the inflated seal-skins are visible again. The instant these are seen, a buoy is elevated on a pole from the nearest canoe, by way of signal; then all dash, with shout and grunt, toward the object of pursuit. Now the chase attains the highest pitch of excitement, for each boat being provided with implements alike, in order to entitle it to a full share of the prize its crew must lodge their harpoon in the animal, with buoys attached; so that, after the first attack is made, the strife that ensues to be next to throw the spear creates a scene of brawl and agility peculiar to these savage adventurers. At length the victim, becoming weakened by loss of blood, yields to a system of torture characteristic of its eager pursuers, and eventually, spouting its last blood from a lacerated heart, it writhes in convulsions and expires. Then the whole fleet of canoes assists in towing it to the shore, where a division is made, and all the inhabitants of the village greedily feed upon the fat and flesh till their appetites are satisfied. After the feast, what oil may be extracted from the remains is put into skins or bladders, and is an article of traffic with neighboring tribes or the white traders who occasionally visit them. These "whales of passage," when arrived in the Arctic Ocean and Okhotsk Sea, are seen emerging between the scattered floes, and even forcing themselves through the field of ice, rising midway above the surface, and blowing in the same |

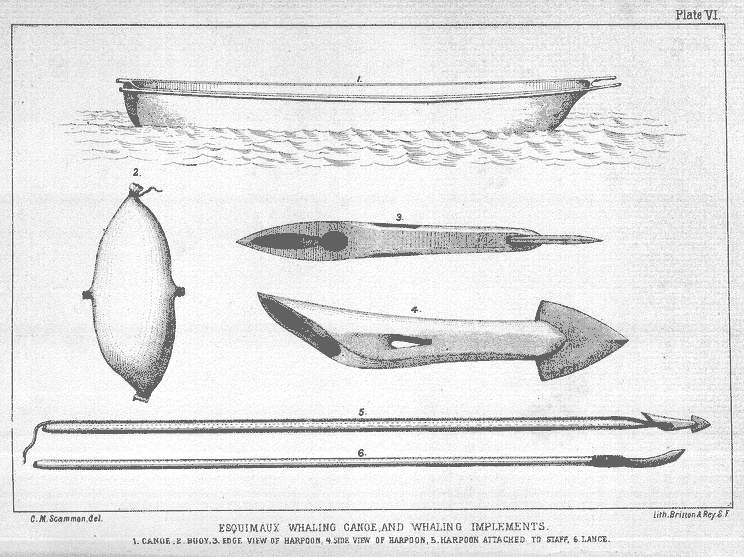

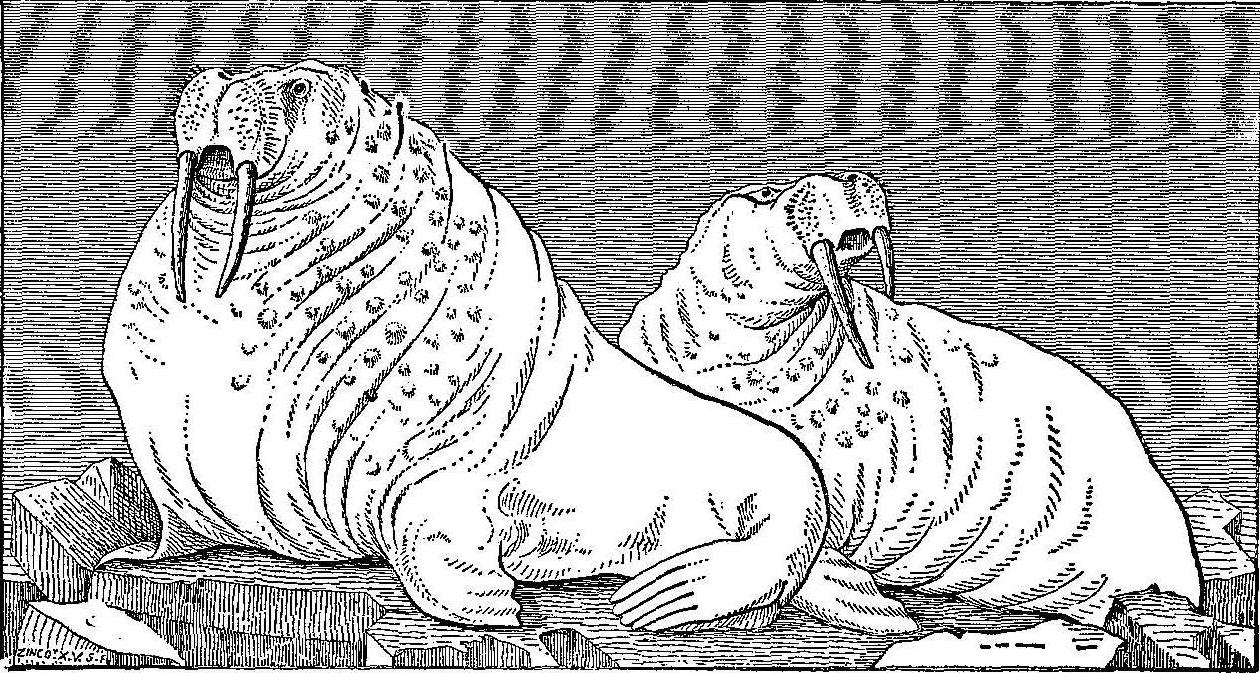

attitude in which they are frequently seen in the southern lagoons; at such times the combined sound of their respirations can be heard, in a calm day, for miles across the ice and water. But in those far northern regions, the animals are rarely pursued by the whale-ship's boats: hence they rest in some degree of security; yet even there, the watchful Esquimaux steal upon them, and to their primitive weapons and rude processes the whale at last succumbs, and supplies food and substance for its captors. The Esquimaux whaling-boat, although to all appearance simple in its construction, will be found, after careful investigation, to be admirably adapted to the purpose, as well as for all other uses necessity demands. It is not only used to accomplish the more important undertaking, but in it they hunt the walrus, shoot game, and make their long summer-voyages about the coast, up the deep bays and long rivers, where they traffic with the interior tribes. When prepared for whaling, the boat is cleared of all passengers and useless incumbrances, nothing being allowed but the whaling-gear. Eight picked men make the crew.* Their boats are twenty-five to thirty feet long, and are flat on the bottom, with flaring sides and tapering ends. The framework is of wood, lashed together with the fibres of baleen and thongs of walrus-hide, the latter article being the covering, or planking, to the boat. The implements are one or more harpoons, made of ivory, with a point of slate-stone or iron; a boat-mast, that serves the triple purpose of spreading the sail and furnishing the staff for the harpoon and lance; a large knife, and eight paddles. The knife lashed to the mast constitutes the lance. The boat being in readiness, the chase begins. As soon as the whale is seen and its course ascertained, all get behind it: not a word is spoken, nor will they take notice of a passing ship or boat, when once excited in the chase. All is silent and motionless until the spout is seen, when they instantly paddle toward it. The spouting over, every paddle is raised; again the spout is seen or heard through the fog, and again they spring to their paddles. In this manner the animal is approached near enough to throw the harpoon, when all shout at the top of their voices. This is said to have the effect of checking the animal's way through the water, thus giving an opportunity to plant the spear in its body, with line and buoys attached. The chase continues in this wise until a number of weapons are firmly fixed, causing the animal much effort to get under water, and still more to remain down; so it soon rises again, and is attacked with renewed vigor. It is the * It is said by Captain Norton, who commanded the ship Citizen, wrecked in the Arctic several years ago, that the women engage in the chase. |

established custom with these simple natives, that the man who first effectually throws his harpoon, takes command of the whole party: accordingly, as soon as the animal becomes much exhausted, his baidarra is paddled near, and with surprising quickness he cuts a hole in its side sufficiently large to admit the knife and mast to which it is attached; then follows a course of cutting and piercing till death ensues, after which the treasure is towed to the beach in front of their huts, where it is divided, each member of the party receiving two "slabs of bone," and a like proportion of the blubber and entrails; the owners of the canoes claiming what remains. The choice pieces for a dainty repast, with them, are the flukes, lips, and fins. The oil is a great article of trade with the interior tribes of "reindeer-men:" it is sold in skins of fifteen gallons each, a skin of oil being the price of a reindeer. The entrails are made into a kind of souse, by pickling them in a liquid extracted from a root that imparts an acrid taste: this preparation is a savory dish, as well as a preventive of the scurvy. The lean flesh supplies food for their dogs, the whole troop of the village gathering about the carcass, fighting, feasting, and howling, as only sledge-dogs can. Many of the marked habits of the California Gray are widely different from those of any other species of balaena. It makes regular migrations from the hot southern latitudes to beyond the Arctic Circle; and in its passages between the extremes of climate it follows the general trend of an irregular coast so near that it is exposed to attack from the savage tribes inhabiting the sea-shores, who pass much of their time in the canoe, and consider the capture of this singular wanderer a feat worthy of the highest distinction. As it approaches the waters of the torrid zone, it presents an opportunity to the civilized whalemen – at sea, along the shore, and in the lagoons – to practice their different modes of strategy, thus hastening the time of its entire annihilation. This species of whale manifests the greatest affection for its young, and seeks the sheltered estuaries lying under a tropical sun, as if to warm its offspring into activity and promote comfort, until grown to the size Nature demands for its first northern visit. When the parent animals are attacked, they show a power of resistance and tenacity of life that distinguish them from all other Cetaceans. Many an expert whaleman has suffered in his encounters with them, and many a one has paid the penalty with his life. Once captured, however, this whale yields the coveted reward to its enemies, furnishing sustenance for the Esquimaux whaler, from such parts as are of little value to others. The oil extracted from its fatty covering is exchanged with remote tribes for their fur-clad animals, of which the flesh affords the venders a feast of the choicest food, |

|

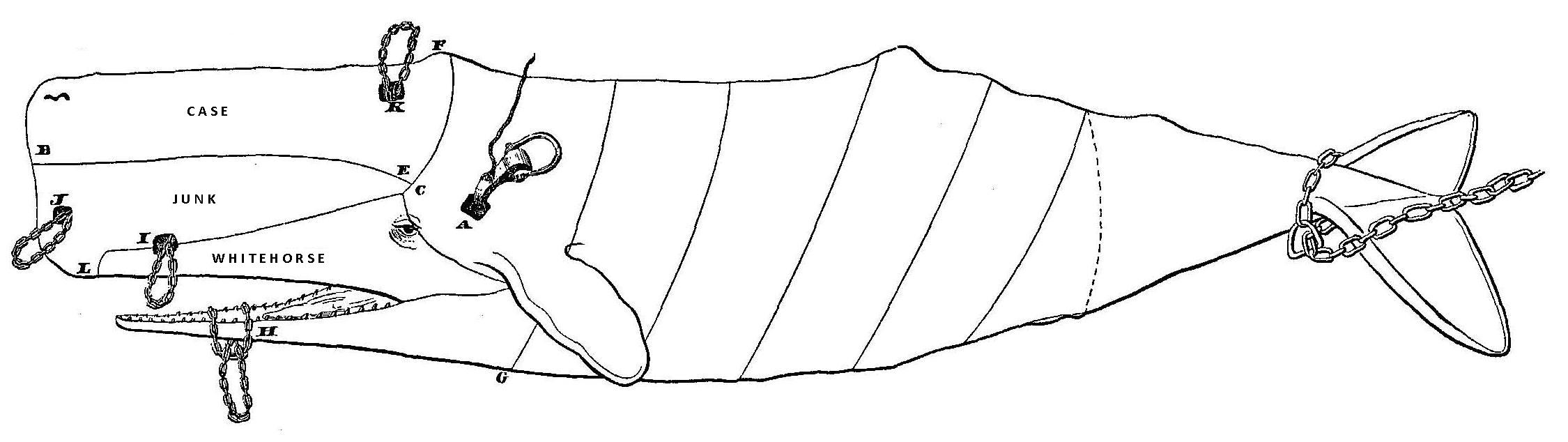

Plate V.

California Grays Among The Ice.

|

and the skins form an indispensable article of clothing. The North-west Indians realize the same comparative benefit from the captured animals as do the Esquimaux, and look forward to its periodical passage through their circumscribed fishing-grounds as a season of exploits and profit. The civilized whaler seeks the hunted animal farther seaward, as from year to year it learns to shun the fatal shore. None of the species are so constantly and variously pursued as the one we have endeavored to describe; and the large bays and lagoons, where these animals once congregated, brought forth and nurtured their young, are already nearly deserted. The mammoth bones of the California Gray lie bleaching on the shores of those silvery waters, and are scattered along the broken coasts, from Siberia to the Gulf of California; and ere long it may be questioned whether this mammal will not be numbered among the extinct species of the Pacific. |

CHAPTER II.THE FINBACK WHALE.

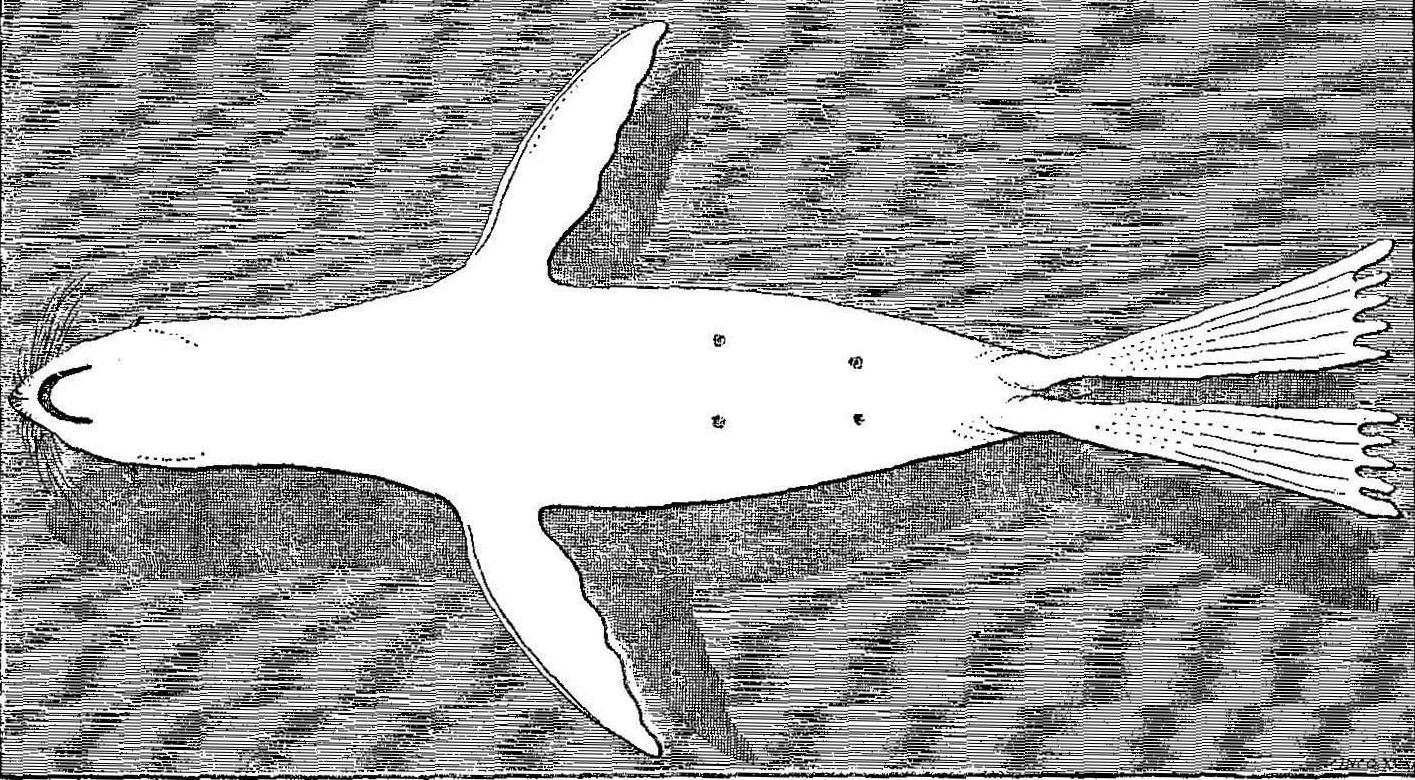

Balaenoptera velifera, Cope. (Plate ii, fig. 2.)

Another species of the whale tribe is known as the Finback, or Finner, whose geographical distribution is as extended as that of the Sulphurbottom, and which ranks next to it in point of swiftness. One picked up by Captain Poole, of the bark Sarah Warren, of San Francisco, affords us the following memoranda: Length, sixty-five feet; thickness of blubber, seven to nine inches; yield of oil, seventy-five barrels; color of blubber, a clear white. Top of head quite as flat and straight as that of the Humpback. Baleen, the longest, two feet four inches; greatest width, thirteen inches; its color, a light lead, streaked with black, and its surface presents a ridgy appearance crosswise; length of fringe to bone, two to four inches, and in size this may be compared to a cambric needle. A Balaenoptera, which came on shore near the outer heads of the Golden Gate, gave us the opportunity of obtaining the following rough measurements:

Its side fins and flukes are in like proportion to the body as in the California Gray. Its throat and breast are marked with deep creases, or folds, similar to the Humpback. Color of back and sides, black or blackish-brown (in some individuals a curved band of lighter shade marks its upper sides, between the spiracles and pectorals); belly, a milky white. Its back fin is placed nearer to the caudal than the hump on the Humpback, and in shape approaches to a right-angled |

triangle, but rounded on the forward edge, curved on the opposite one; the longest side joins the back in some examples, and in others the anterior edge is the longest. The gular folds spread on each side to the pectorals, and extended half the length of the body. The habitual movements of the Finback in several points are peculiar. When it respires, the vaporous breath passes quickly through its spiracles, and when a fresh supply of air is drawn into the breathing system, a sharp and somewhat musical sound may be heard at a considerable distance, which is quite distinguishable from that of other whales of the same genus. (We have observed the interval between the respirations of a large Finback to be about seven seconds.) It frequently gambols about vessels at sea, in mid-ocean as well as close in with the coast, darting under them, or shooting swiftly through the water on either side; at one moment upon the surface, belching forth its quick, ringing spout, and the next instant submerging itself beneath the waves, as if enjoying a spirited race with the ship dashing along under a press of sail. In beginning the descent, it assumes a variety of positions: sometimes rolling over nearly on its side, at other times rounding, or perhaps heaving, its flukes out, and assuming nearly a perpendicular attitude. Frequently it remains on the surface, making a regular course and several uniform "blows." Occasionally they congregate in schools of fifteen to twenty, or less. In this situation we have usually observed them going quickly through the water, several spouting at the same instant. Their uncertain movements, however – often showing themselves twice or thrice, then disappearing – and their swiftness, make them very difficult to capture. The results of several attempts to catch them were as follows: from the ship one was shot with a bomb-gun, which did its work so effectually, that although the boat was in readiness for instant lowering, before it got within darting distance the animal, in its dying contortions, ran foul of the ship, giving her a shock that was very sensibly felt by all on board, and likewise a momentary heel of about two streaks. We had a good view of the under-side of the whale as it made several successive rolls before disappearing, and our observations agreed with those noted on board the Sarah Warren in relation to color and the creases on throat and breast. The under-side of the fins was white also. At another time the whale died about ten fathoms under water, and after carefully hauling it up in sight, the "iron drawed, and away the dead animal went to the depths beneath." Frequently we have "lowered" for single ones that were playing about the ship, but by the time the boats were in the water nothing more would be seen of them, or, if seen, they would be a long way off, and then disappear. An instance occurred in Monterey Bay, in 1865, of five being captured under |

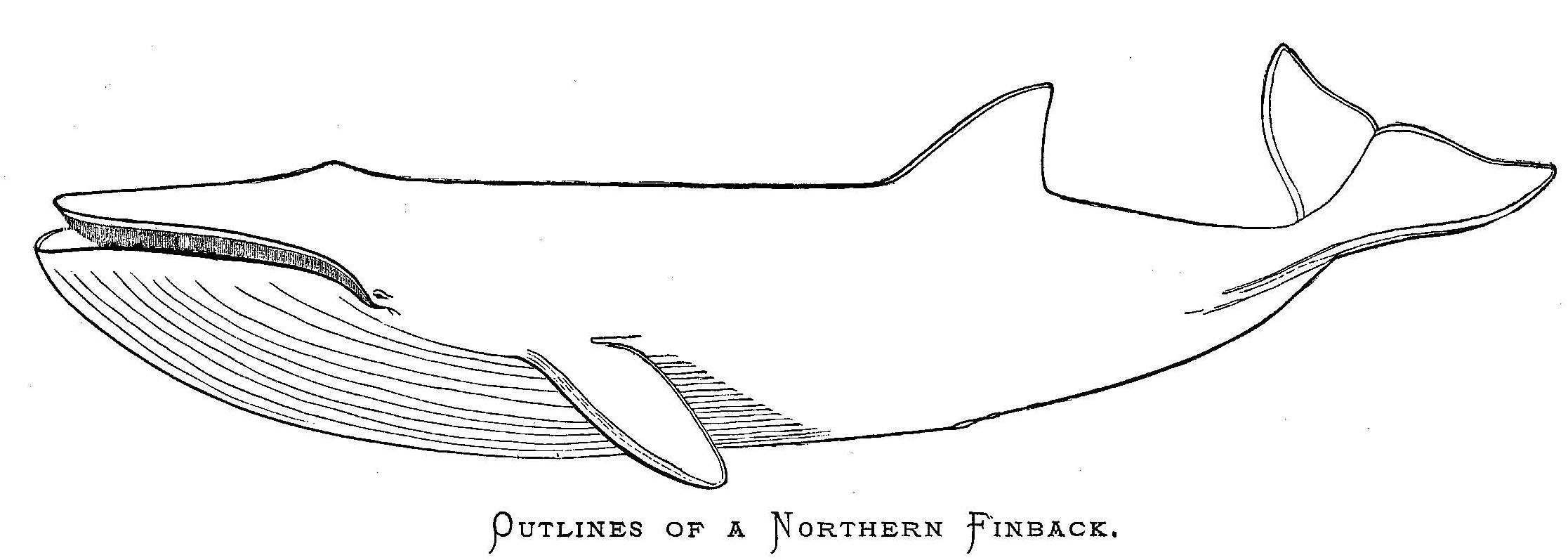

the following circumstances: A "pod" of whales was seen in the offing, by the whalemen, from their shore station, who immediately embarked in their boats and gave chase. On coming up to them they were found to be Finbacks. One was harpooned, and, although it received a mortal wound, they all "run together" as before. One of the gunners, being an expert, managed to shoot the whole five, and they were all ultimately secured, yielding to the captors a merited prize. We have noticed large numbers of these whales along the coast during the summer months, and they seem to be more together at that particular season; but, as the opportunities for observing their habits have been much greater at that time of the year, we may have been led into error upon this particular point. Their food is of the same nature as that of the other rorquals, and the quantity of codfish which has been found in them is truly enormous. On the northern coast, the Finbacks, in many instances, have a much larger fin than those in warmer latitudes, and we are fully satisfied that these are a distinct species, confined to the northern waters. We have had but little opportunity to observe the Finbacks that frequently rove about the Gulf of Georgia and Fuca Strait. Several have been seen, however, in May and June, on the coasts of California and Oregon, and in Fuca Strait in June and July of the year 1864; these observations satisfy us that the dorsal fin of this – the northern species referred to – is strikingly larger than in the more southern Finbacks. Appended are the outlines of one individual of several seen in Queen Charlotte Sound, in February, 1865, which is a fair representation of them all. Those we have noticed about Fuca Strait seem to have the back fin modified in size between the extremely small one found on the coast of Lower California and the one here represented. |

|

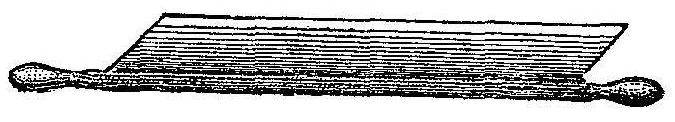

Plate VI.

Esquimaux Whaling Canoe, and Whaling Implements.

1. Canoe. 2. Buoy. 3. Edge View of Harpoon. 4. Side View of Harpoon.

5. Harpoon Attached to Staff. 6. Lance. |

Outlines of a Northern Finback.

|

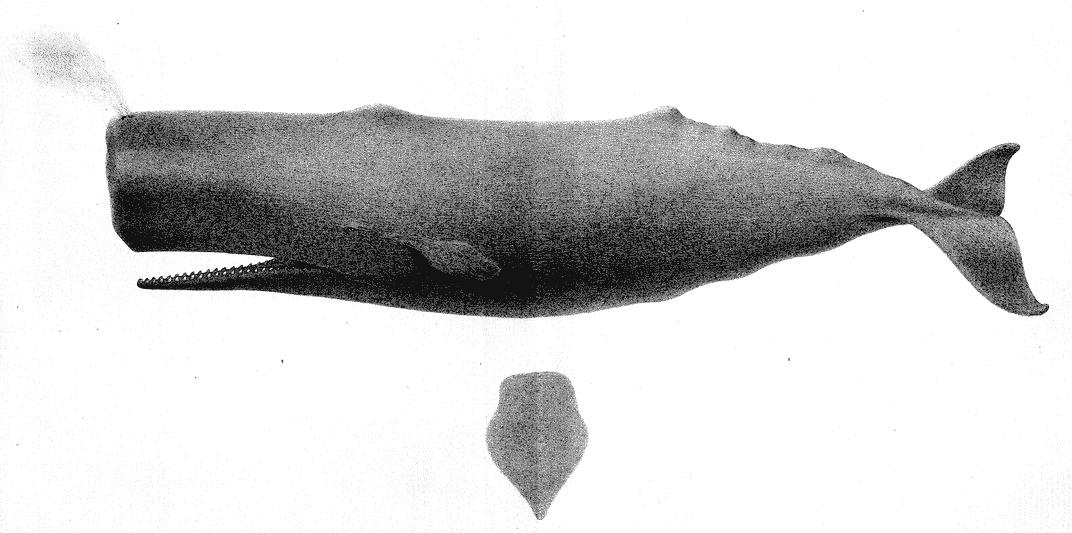

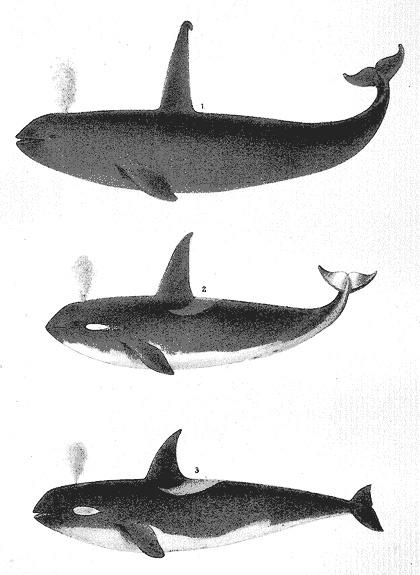

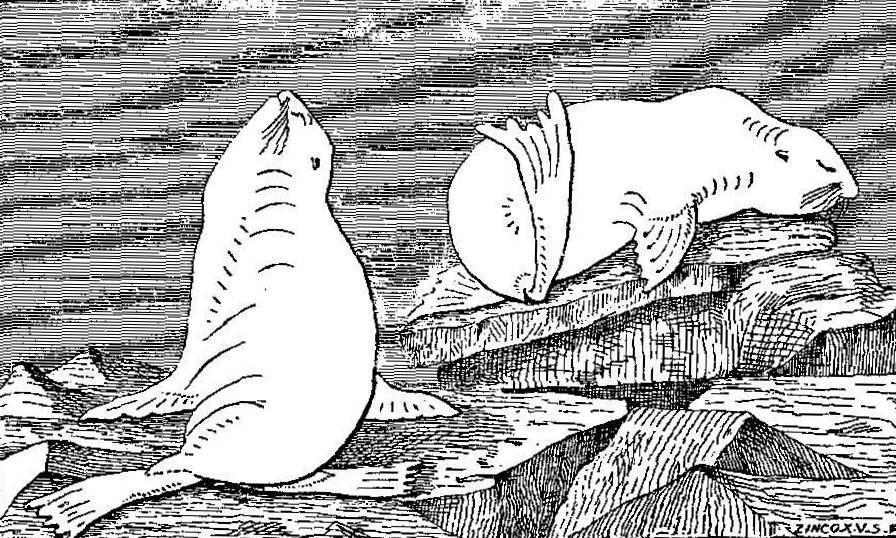

CHAPTER III.THE HUMPBACK WHALE.

Megaptera versabilis, Cope. (Plate vii, fig. 1.)

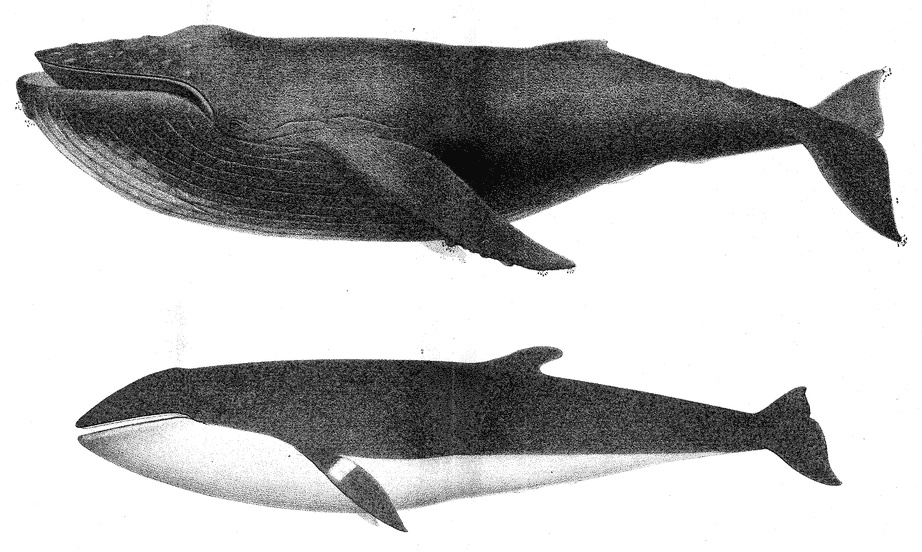

The Humpback is one of the species of rorquals that roam through every ocean, generally preferring to feed and perform its uncouth gambols near extensive coasts, or about the shores of islands, in all latitudes between the equator and the frozen oceans, both north and south. It is irregular in its movements, seldom going a straight course for any considerable distance; at one time moving about in large numbers, scattered over the sea as far as the eye can discern from the mast-head; at other times singly, seeming as much at home as if it were surrounded by hundreds of its kind; performing at will the varied actions of "breaching," "rolling," "finning," "lobtailing," or "scooping;" or, on a calm, sunny day, perhaps lying motionless on the molten-looking surface, as though life were extinct. Its shape, compared with the symmetrical forms of the Finback, California Gray, and Sulphurbottom, is decidedly ugly, as it has a short, thick body, and frequently a diminutive "small," with inordinately large pectorals and flukes. A protuberance, of variable shape and size in different individuals, placed on the back, about one-fourth the length from the caudal fin, is called the hump. Another cartilaginous boss projects from a centre fold immediately beneath the anterior point of the under jaw, which, with the flukes, pectorals, and throat of the creature, are oftentimes hung with pendent parasites* (Otion Stimpsoni), and on * We print here Dall's description of the Cyamus suffusus; also his remarks on the Otion Stimpsoni (Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci., Dec. 18th, 1872). Illustrations, figures 3 and 5, plate x. Cyamus suffusus, n. sp. Body flattened, elongate; segments, sub-equal, outer edges widely separated. Branchiae single, cylindrical slender, with a very short papilliform appendage before and behind each branchia. Superior antennae unusually long and stout. First pair of hands quadrant-shaped; second pair slightly punctate, arcuate, emarginate on the inferior edge, with a pointed tubercle on each side of the emargination. Third joint of the posterior legs keeled above, with a prong below. Pleon extremely minute. Segments smooth. No ventral spines on posterior segments. Color, yellowish white, suffused with rose-purple, strongest upon the antennae and branchiae. Length, 0.41 inches; |

the males it is frequently studded with tubercles, as upon the head. A bulge also rounds down on the lower part of the "small," nearly midway between the hump and caudal. Its under jaw extends forward considerably beyond the upper one. All these combined characteristics impress the observer with the idea of an animal of abnormal proportions. The top of its head is dotted with irregular, rounded bunches, which rise about one inch above the surface, each covering nearly four square inches of space. The following measurements and memoranda of a male Humpback were taken by Captain F. S. Redfield, of the whaling and trading brig Manuella, while cruising in Behring Sea, September 17th, 1866:

breadth (of body), 0.25 inches. All the specimens which have passed under my observation, some eight or ten in number, were males. Habitat, on the Humpback Whale (Megaptera versabilis, Cope) Monterey, California. Otion, Leach. Otion, Leach. Ency. Britannica, suppl. vol. iii, p. 170. Otion Stimpsoni, Dall, n. sp. Scuta only present, beaked, with the umbones on the occludent margins; anterior prolongation the longer, pointed, rather slender; posterior prolongation, rounded, wider; external margin concave; color (in spirits), light orange, with a dark purple streak on the rostral surface and on each side of the peduncle; while the lateral surfaces of the body-case and lobes are mottled with dark purple. The lower lip of the orifice is transversely striated and translucent; the upper margins slightly reflexed internally, white; in some specimens with two prolongations or small lobes above, which are wanting in other specimens. The tubular prolongations very irregular and variable in size and form, usually unsymmetrical; one sometimes nearly abortive. Length of peduncle, 2.08 inches; of body, 2.16 inches; of lobes, 2.00 inches; of orifice, 1.18 inch; of scuta, 0.55 inch; width of scuta, 0.16 inch. Habitat, on the Humpback (M. versabilis); sessile on the Coronulae which infest that species, but never, so far as I have observed, on the surface of the whale itself. Dr. Leach describes five calcareous species, having the scuta, terga, and rostrum of the typical species (O. Cuvieri, Leach) and they are figured by Reeve; but this species has certainly only the scuta. Whether this difference is of more than specific value I am not able to decide, owing to the great paucity of works of reference here. I should be unwilling to describe the species, were it not that it was submitted to the late lamented Dr. Stimpson for examination, and was pronounced by him to be new. |

Thickness of blubber, five to ten inches; color of blubber, yellowish white; yield of oil, forty barrels; number of folds on belly, twenty-six, averaging from four to six inches in width. These folds, which extend from the anterior portion of the throat over the belly, terminating a little behind the pectorals, are capable of great expansion and 'contraction, which enables the Humpbacks, as well as all other rorquals, to swell their maws when their food is in abundance about them. The following additional measurements, etc., were taken from Humpbacks captured on the coast of Upper California, in 1872. 1. Sex, female. Color of body, black above, but more or less marbled with white below. Fins, black above, and dotted with white beneath. Color of blubber, white. Number of folds on throat and breast, twenty-one, the widest of which were six inches. Yield of oil, thirty-five barrels. The yield of bone, which is of inferior quality, is about four hundred pounds to a hundred barrels of oil.

The nib-end, or point of the upper jaw, fell short of the extremity of the * We refer the reader to fig. 4, plate x, for illustration of an eye taken from a Humpback forty-six feet in length. The figure is drawn to natural size. |

|

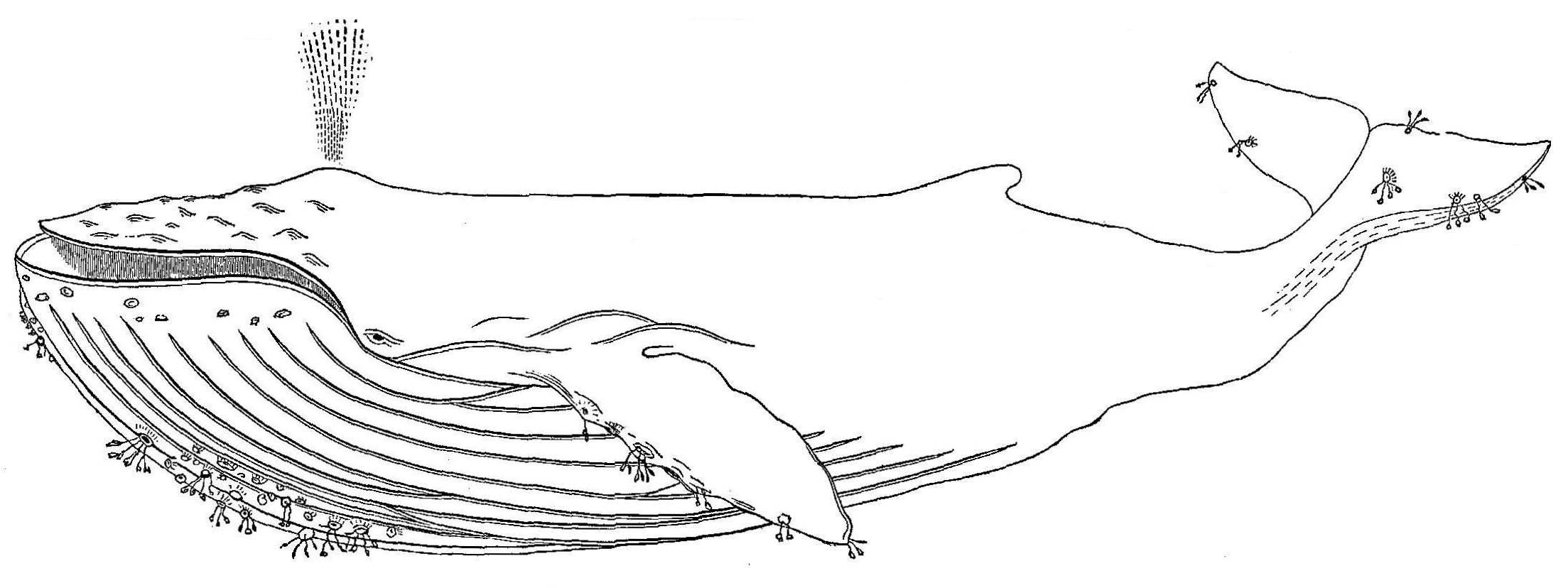

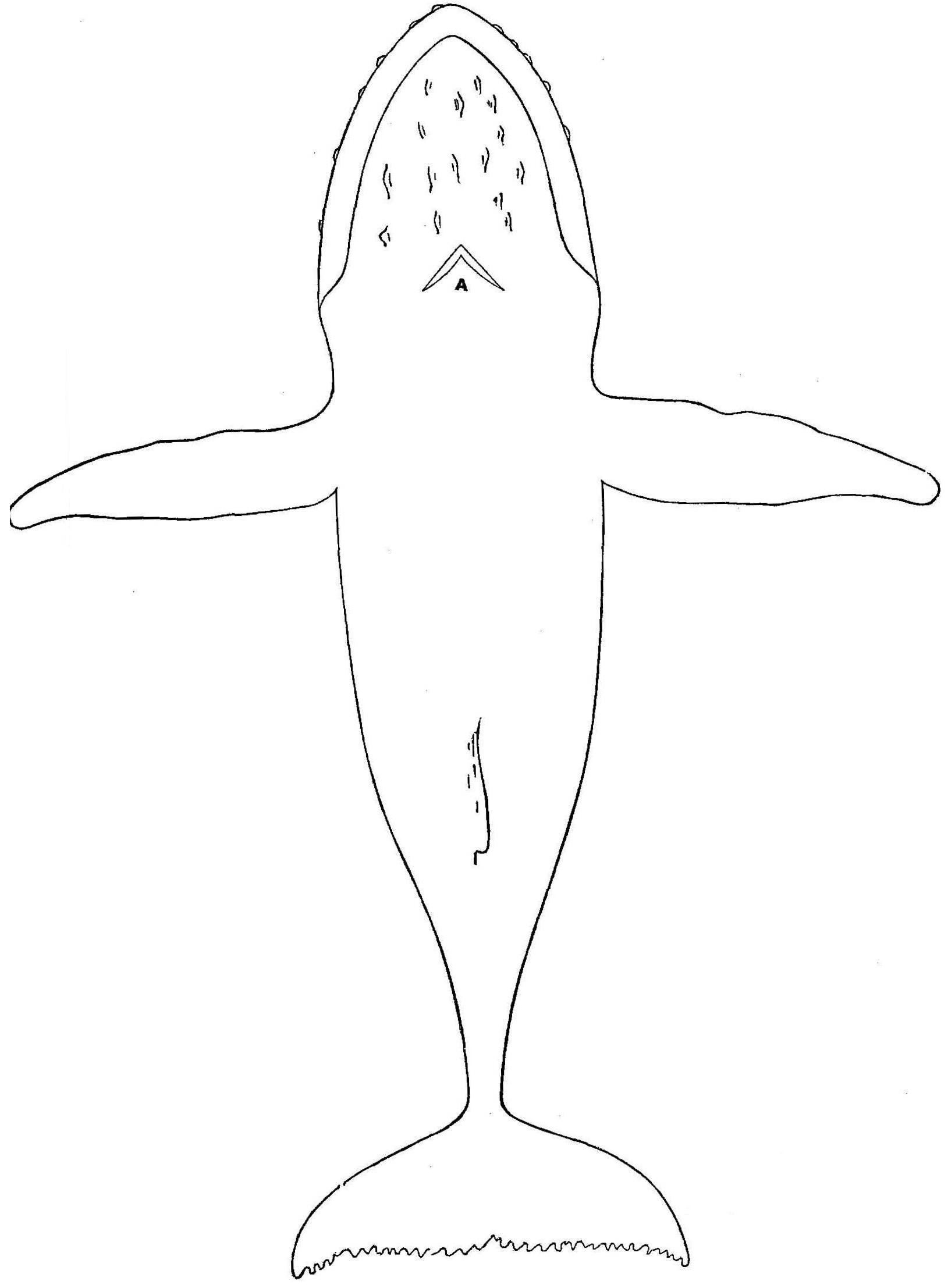

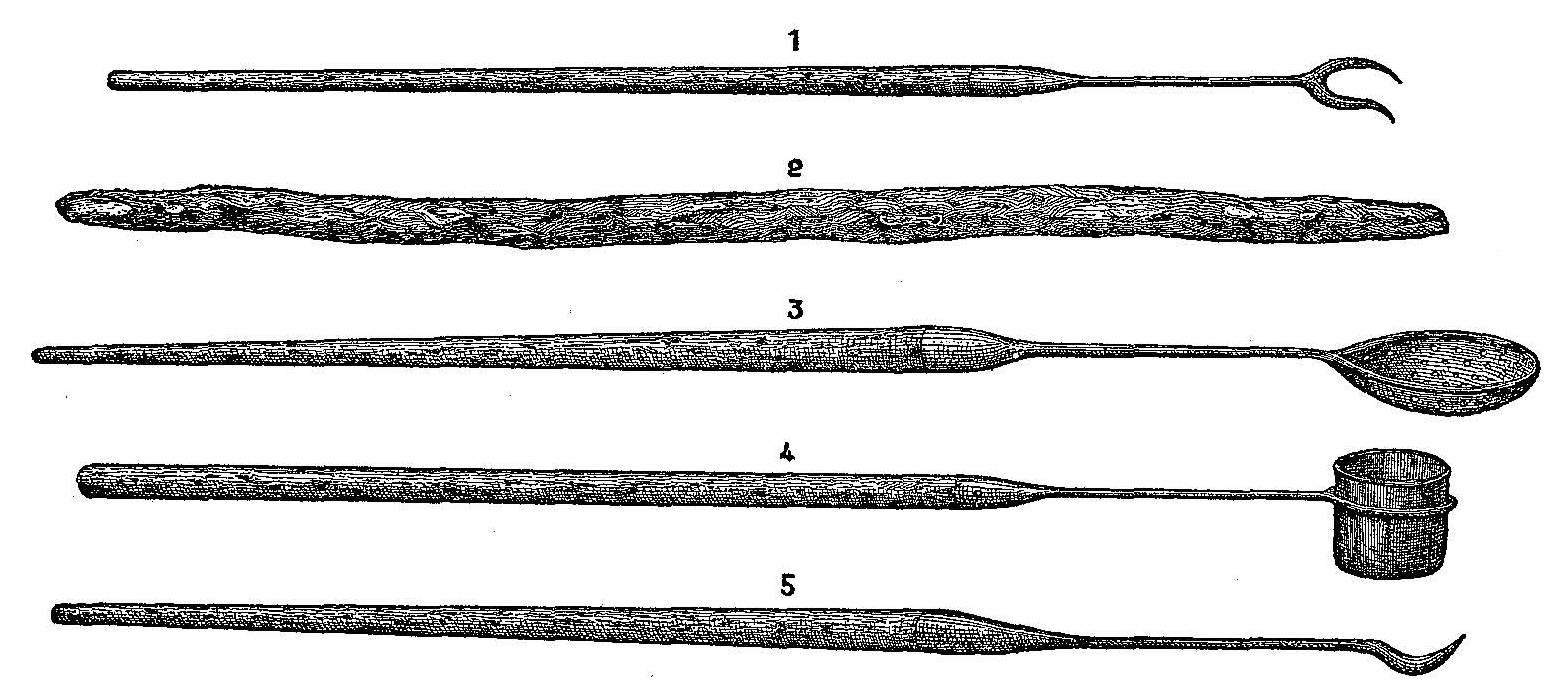

Plate VII.

1. Humpback (Megaptera Versabilis Cope.) 2. Sharp-Headed Finner.

|

lower one about fifteen inches. The tongue and throat were of a leaden color. The orbit of the eye was four inches in diameter. The longest plate of bone, or baleen, was two feet; its color, black, with a fringe of lighter shade. 2. Sex, female. Color of body, black, with slight marks of white beneath. Color of pectorals, black above, white below. Color of flukes, black above and below. Color of blubber, white; average thickness of same, six inches. Yield of oil, thirty barrels. Gular folds, eighteen. Tubercles on lips, nine.

3. Sex, female. Color of body, black above, slightly mottled with white and gray below. Fins and flukes, black above, white beneath. Color of blubber, white; thickness of same, six to nine inches. Yield of oil, forty barrels. Number of laminae, five hundred and forty; black, streaked with white, or light lead color.

It is proper to state, that the dimensions of the skull, or upper jaw-bone, of any ordinary sized animal would be about fifteen feet long by six broad. The lower jaw-bones, which are joined by a slight symphysis, are each about the same length in their curves, and are about one foot wide and eight inches thick midway between the extremities. The thickness of the lumbar vertebrae is about eight inches; the distance between the points of the spurs, two feet eight inches; and the weight, twenty-four or more pounds. The largest ribs are from nine to twelve feet long, measured on the curve, and ten to fifteen inches in circumference. The aggregate weight of two well-dried specimens (measuring respectively nine and ten feet) was eighty pounds. The first joint of the pectoral bones may be set down at two and a half feet in length, and the same in circumference at its union with the shoulder-blade. This section of the fin bones exceeds fifty pounds in weight. The usual color of the Humpback is black above, a little lighter below, slightly marbled with white or gray; but sometimes the animal is of spotless white under the |

fins and about the abdomen. The posterior edge of the hump, in many examples, is tipped with pure white. The megaptera varies more in the production of oil than all others of the rorquals. We have frequently seen individuals which yielded but eight or ten barrels of oil, and others as much as seventy-five; the length of the animal varying from twenty-five to seventy-five feet. Most of these variations may be attributed to age and sex, as the female with a large cub becomes quite destitute of fat in her covering. These animals, more especially the smaller or younger ones, are infested with parasitic crustaceans (Cyamus suffusus), which collect in great numbers about the head and pectorals; or, in case there are any wounds upon the body, these troublesome vermin are sure to find them. On the coast of California, in 1856, we captured a whale of ordinary size, which had many patches of these parasites united almost in one mass upon that portion of the body which was exposed when the animal came to the surface, and when "cut in" it proved to have what is termed a "dry skin," the blubber being destitute of oil; this was attributed to the abundance of these troublesome parasites. The Humpback has also the largest barnacles adhering to, or imbedded in, the epidermis, about the throat or fins. The habits of this whale – particularly in its undulating movements, frequent "roundings," "turning of flukes," and irregular course – are characteristic indications, which the quick and practiced eye of the whaleman distinguishes at a long distance. Even when beneath the surface of the sea, we have observed them just "under the rim of the water" (as whalemen used to say), alternately turning from side to side, or deviating in their course with as little apparent effort, and as gracefully, as a swallow on the wing. Like all other rorquals, it has two spiracles, and when it respires, the breath and vapor ejected through these apertures form the "spout," and rises in two separate columns, which, however, unite in one as they ascend and expand. When the enormous lungs of the animal are brought into full play, the spout ascends twenty feet or more. When the whale is going to windward, the influence of the breeze upon the vapor is such, that a low, bushy spout is all that can be seen. The number of respirations to a "rising" is exceedingly variable: sometimes the animal blows only once, at another time six, eight, or ten, and from that up to fifteen or twenty times. Although the Humpbacks are found in every sea and ocean, our observations indicate that they resort periodically, and with some degree of regularity, to particular localities, where the females bring forth their young. It seems, moreover, that large numbers of both sexes make a sort of general migration from the warmer to the colder latitudes, as the seasons change. They go north in the northern hemisphere, as summer approaches, and return south when winter sets in. |

The following observations were made along the coasts of North and South America, and in Oceanica. In the years 1852 and 1853, large numbers of Hump-backs resorted to the Gulf of Guayaquil, coast of Peru, to calve, and the height of the season was during the months of July and August. The same may be said of the gulfs and bays situated near the corresponding latitudes north of the equator; still, instances are not unfrequent where cows and their calves have been seen at all other seasons of the year about the same coast. In the Bay of Valle de Banderas, coast of Mexico (latitude 20° 30'), in the month of December, we saw numbers of Humpbacks, with calves but a few days old. In May, 1855, at Magdalena Bay, coast of Lower California (about latitude 24° 30'), we found them in like numbers; some with very large calves, while others were very small. The season at Tongataboo (one of the Friendly Islands, latitude 21° south, longitude 174° west), according to Captain Beckerman, includes August and September. Here the females were usually large, yielding an average of forty barrels of oil, including the entrail fat, which amounted to about six barrels. The largest whale taken at this point, during the season of 1871, produced seventy-three barrels, and she was adjudged to be seventy-five feet in length. It is worthy of remark, that a large majority of the whales resorting thither were white on the under side of the body and fins.* * Eminent zoologists have divided the Hump-backs into several species. Gray, in his Catalogue of the British Museum, 1850, makes mention of the following names and outward descriptions: 1. Megaptera Longimana (Johnston's Humpback Whale). – Black, pectoral fins and beneath white, black varied; lower lip with two series of tubercles; pectorals nearly one-third the entire length; dorsal elongate, the front edge over end of pectoral; throat and belly grooved. Female: upper and lower lip with a series of tubercles; dorsal an obscure protuberance. 2. Megaptera Americana (Bermuda Humpback). – Black, belly white; head with round tubercles. 3. Megaptera Poeskop (Poeskop or Cape Humpback). – Dorsal nearly over the end of pectorals. 4. Megaptera Kuzira (The Kuzira). – Dorsal small, and behind the middle of the back; the pectoral fins rather short, and less than one-fourth the entire length of the body; nose and sides of throat have round warts; belly plaited. We have frequently recognized, upon the California coast, every species here described, and even in the same school or "gam." Moreover, we have experienced the greatest difficulty in finding any two of these strange animals externally alike, or possessing any marked generic or specific differences. If the differences pointed out as constituting different species are maintained, we conclude there must be a great number. We have observed, both in the dead and living animals, the following different external marks: 1st. Body black above, white beneath. 2d. Body black above and below, with more or less white mottling under the throat and about the abdomen; pectoral and caudal fins white beneath, or slightly spotted with black. 3d. Body black above, white beneath, |

In the Bay of Monterey, Upper California, the best season for Humpbacks is in the months of October and November; but some whales are taken during the period from April to December, including a part of both of those months. The great body of these whales, however, are observed working their way northward until September, when they begin to return southward; and the bay being open to the north, many of the returning band follow along its shores or visit its south-ern extremity, in search of food, which consists principally of small fish and the lower orders of crustaceans. When the animals are feeding, the whalers have a very favorable opportunity for their pursuit and capture. The observations of the whaling parties, which have been established at this bay for over seventeen years, furnish reliable data in reference to the periodical movements of whales along the Pacific Coast. Of the Humpbacks, individuals of every variety, size, and age have been taken, including one of the most gigantic specimens of the genus. This animal, which yielded one hundred and forty-five barrels of oil, was taken in 1858, when the usual school of large megapteras was making its annual passage south-ward. One of the largest of these whales having an unusual mark – a white spot on the hump?was recognized for several years in succession in its periodical mi- with under side of pectoral and caudal fins of a dark ash-color. 4th. Body black above, with gray mottling beneath. In all these varieties, both the caudal and pectoral fins differ in shape and size; the latter in some individuals being exceedingly long, narrow, and pointed, as represented in figure 1 of plate vii; while others are comparatively short and broad, as shown in the outline (page 47), which also shows the parasites, commonly called barnacles, adhering to the throat, pectorals, and caudal fin. There are still others whose pectorals are of intermediate proportions, but terminate abruptly, as seen on page 48, which also represents the scalloped flukes present in some individuals. (In this figure, the mark "A" shows the outlines of spiracles, which form nearly a right angle). Again, in other examples, the caudal fin is narrow, pointed, and lunate; in others, still, it is broad, and nearly straight on the posterior edge. All these varieties feed and associate together on the same ground, and in every particular their habits are the same, so far as we have been able to ascertain from careful observation; all, likewise, are infested by the same parasites. As to the dorsal protuberance called the hump, it is, as has been previously stated, of no regular shape or size, but is nearly of a uniform height; the posterior edge is sometimes tipped with white. As to the tubercles on the head and lips, they were present on all we have examined, twenty or more specimens; those about the head are always well-developed, while those upon the lips, in many individuals, are scarcely perceptible. In some instances, however, they equal or exceed those which crown the skull. There is no regularity in the number of gular folds, which, as far as observed, vary in number from eighteen to twenty-six. In some cases they run parallel to each other; but usually there are several that either cross or terminate near the pectorals. The animals are all described as being black above; but in the examples which have been examined, there was not one, when closely scrutinized, which did not reveal some slight marks of white. |

|

Plate VIII.

Humpbacks Lobtailing Bolting Breaching and Finning.

|