Portraits of Captain David Porter,

United States Frigate Essex

Left: 1814 engraving by David Edwin, from a painting by Joseph Wood (location unknown) for Analectic Magazine, Vol. IV, p. 225. Also in Porter's Journal, 1st edition.

Right: 1862 engraving published by Johnson, Fry & Co. Inscription reads: “From the original painting by Alonzo Chappel in the possession of the publishers.” (location unknown).§

§ Alonzo Chappel (1828-1887) was two years old when Porter was Consul General at Algiers, and fifteen years old when Porter died. Therefore, his painting of Porter was apparently not done during the subject's lifetime. Also, the above engraving closely resembles that of David Edwin—note position of Porter's left hand, buttons on his uniform, etc. Furthermore, the same engraving is seen at the Alonzo Chappel website, where it is listed as a painting (not an engraving). These details suggest that perhaps a Chappel painting does not exist, and that the artist (or someone on his staff) created the engraving based on Edwin's earlier work.

1818-19 Oil painting by Charles Willson Peale

Entry in Peale's Diary: “ [Porter] thought that I had made it too handsome for him. I find that he is one of those characters who puzzle portrait painters who undertake to portray them. He is seldom a minute in the same position, for when anyone speaks he turns toward them and never thinks that it is necessary to keep himself in the same view to the painter. So that the painter, having formed his design, must watch to sketch the traits as quick as possible.”

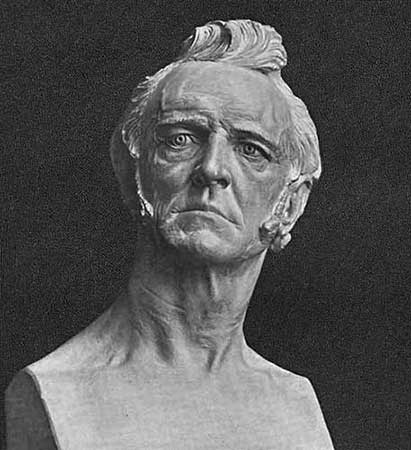

Left: 1825 life mask by John Henri Isaac Browere.

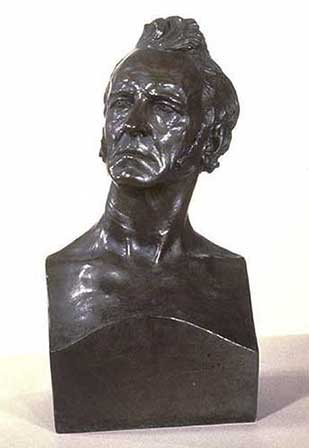

Right: 1940 bronze bust by Roman Bronze Works, from Browere's life mask.

1825: Letter from David Porter to Major Mordecai M. {Manuel} Noah

Meridian Hill, 18th Sept. 1825.

Dear Sir:

By means of epistolary introduction I have had the pleasure of becoming acquainted with John H. I. {Henri Isaac} Browere, Esq., a young and deserving artist of your city. Agreeably to your and my friends' requests, I consented to sit for my portrait bust, which has been executed by him according to his novel and perfect mode. Mr. Browere has succeeded to admiration. Nothing can be more accurate and expressive; in fact, it was impossible that it could be otherwise than a perfect facsimile of my person, owing to the peculiar neatness and dexterity which guide his scientific operation. The knowledge and dexterity of Mr. Browere in this branch of the Fine Arts is surprising, and were I to express my opinion on the subject, I should recommend every one who wished to possess a perfect likeness of himself or friends to resort to Mr. Browere in preference to any other man. His portrait busts are chef d'oevres in the plastic art, unequalled for beauty and correct delineation of the human form. To those to whom a saving of time is important, Mr. Browere's method must receive the preference, were it solely on that ground. As to the effect of the operation, none need apprehend the least danger or inconvenience; it is perfectly safe and not disagreeable, for while the plastic material is applying to the skin, a sensation both harmless and agreeable produces a pleasant glow or heat somewhat similar to that which is felt on entering a warm bath; neither does the composition affect the eyes, which are covered with it. Too much commendation of Mr. Browere's rare and invaluable invention cannot be made. May he derive benefits from his art equal to his merit. Hoping to have the pleasure of seeing my friends in New York during the course of a few weeks, I remain, Dear Sir,

Your obt. servant

David Porter.

Images resized so that distance between eyes is the same.

The David Edwin engraving (left) published in Analectic Magazine (1814) suggests the subject was of short stature, and in the accompanying biography, Porter's friend Washington Irving refers to his “feeble frame.” The Captain's son, David Dixon Porter, also mentions the fragile frame of his father. David Long's biography of Porter (Nothing Too Daring) notes that “—one nineteenth century historian { Charles Jared Ingersoll, but unidentified by Long} described him as ‘a small, slight, and rather ill-favored New England man’—.”§ As for the 1825 Browere life mask (right), note that Porter himself stated that “Nothing can be more accurate and expressive.” Both images display a distinctive tuft of hair at the top of the subject's head and extended sideburns.

§ Ingersoll, History of the Second War Between the United States of America and Great Britain. Vol. I, p. 12, para. 2. Philadelphia, 1852: Lipincott, Grambo & Co.

The similarity between the engraving and the life mask raises a question about the identity of the person seen in Charles Willson Peale's portrait (center), which was created about midway between the other two images. The sitter's demeanor does not agree with Peale's description of Porter. In fact, for the sitter to be Porter, he would have had to change his hair style, shave his sideburns, alter his facial characteristics, and acquire the more robust physique suggested by Peale's portrait. And then he would have to revert to his former appearance before Browere created his life mask. Since this seems unlikely (to say the least), the subject of the Peale portrait is presumably someone other than David Porter.